Abstract

Background and Objective

It is critical to evaluate cancer survivors’ preferences when developing follow-up care models to better address the needs of cancer survivors. This study was conducted to understand the key attributes of breast cancer follow-up care for use in a future discrete choice experiment (DCE) survey.

Methods

Key attributes of breast cancer follow-up care models were generated using a multi-stage, mixed-methods approach. Focus group discussions were conducted with cancer survivors and clinicians to generate a range of attributes of current and ideal follow-up care. These attributes were then prioritised using an online survey with survivors and healthcare providers. The DCE attributes and levels were finalised via an expert panel discussion based on the outcomes of the previous stages.

Results

Four focus groups were held, two with breast cancer survivors (n = 7) and two with clinicians (n = 8). Focus groups generated sixteen attributes deemed important for breast cancer follow-up care models. The prioritisation exercise was conducted with 20 participants (14 breast cancer survivors and 6 clinicians). Finally, the expert panel selected five attributes for a future DCE survey tool to elicit cancer survivors’ preferences on breast cancer follow-up care. The final attributes included: the care team, allied health and supportive care, survivorship care planning, travel for appointments, and out-of-pocket costs.

Conclusions

Attributes identified can be used in future DCE studies to elicit cancer survivors’ preferences for breast cancer follow-up care. This strengthens the design and implementation of follow-up care programs that best suit the needs and expectations of breast cancer survivors.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

The development of attributes for use in discrete choice experiments and preference-based studies need to be rigorously reported to ensure appropriate findings. |

Attributes of breast cancer follow-up care that are most important to patients and healthcare providers are related to the care team, holistic nature of care, survivorship care coordination, travel for appointments and out-of-pocket costs. |

Understanding the most highly valued attributes of breast cancer follow-up care and other related considerations can influence policymakers decisions when implementing survivorship care. |

1 Introduction

Breast cancer is the most commonly diagnosed cancer among Australian women [1]. In 2017, there were 17,589 new cases of breast cancer among women in Australia with an overall 5-year survival rate of 91% [2]. With advances in treatment and early detection programs, the survival rate of women diagnosed with breast cancer continues to improve. More women are living longer after diagnosis and treatment consequently requiring ongoing quality cancer survivorship care [2]. Comprehensive follow-up care for breast cancer after primary treatment typically focuses on improving the overall wellbeing of breast cancer survivors, including regular surveillance for cancer recurrence or progression, screening for secondary cancers, management of physical effects and psychosocial issues of cancer and its treatment, health promotion, and management of comorbidities [3]. There is a growing emphasis on improving the consistency and quality of cancer survivorship care [4], while providing a service that adequately meets the survivor’s needs and effectively improves outcomes concerning symptom management, physical and psychosocial health, and ultimately the quantity and quality of life [5].

Traditionally, post-treatment follow-up care for breast cancer survivors has been specialist-led in hospital and specialist clinic settings [6]. Follow-up care by a cancer specialist is primarily focused on detecting recurrence and the impact of treatment or late-stage disease can incur high costs [7] that may be unsustainable in a typically under-resourced and over-burdened acute care system with rising new cancer diagnoses requiring rapid treatment [6]. Alternatives to specialist-led follow-up care, such as shared-care arrangements between specialists and primary care, primary care-led care, and nurse-led care [6, 8, 9] have been implemented and evaluated in certain settings but are not widespread. Studies have shown that alternative approaches to follow-up cancer care such as nurse-led and shared-care models may reduce health care costs. These may be more acceptable to patients as they provide shorter waiting and travel times, while not significantly differing from specialist-led follow-up care concerning effectiveness on healthcare outcomes and quality of care [6].

In the era of patient-centric health care, the success of any health care program depends on how well it is suited to the needs of the cancer survivors. The Institute of Medicine (IOM) report on cancer survivorship care highlighted the importance of incorporating health care providers, consumer advocates, and other stakeholders in designing appropriate survivorship care [10]. Hence, understanding important attributes and patient preferences is a useful way of ensuring models of care align with patient needs and are fit for purpose. A discrete choice experiment (DCE) survey method has been used widely in a range of health areas outside of cancer follow-up care to elicit patient and public preferences for different aspects of healthcare services [11, 12]. Individuals are presented with a number of hypothetical health scenario choice sets, each containing two or more alternatives with different attributes (characteristics) from which individuals are asked to choose [13]. Previous studies have used the DCE method to evaluate genetic counselling for cancer survivors, cancer screening programs, and cancer treatments [14, 15]. Nevertheless, evidence using the DCE method is very limited on how cancer survivors make choices concerning different features of their cancer follow-up care [16].

Cancer survivors’ preferences specifically for breast cancer follow-up care have previously been investigated using the DCE method however, these studies used existing qualitative literature to understand the attributes for use in, and to inform, the DCE survey [17, 18]. Additionally, although these studies evaluated preference for specialist-led, nurse-led, or primary care-led models, they did not include initiatives such as shared care between specialists and primary care [17]. Hence, a comprehensive and contemporary study exploring how breast cancer survivors value the different attributes of various breast cancer follow-up care models that also incorporates shared-care arrangements is useful for proper planning and effective future utilisation of health care resources. Identifying and prioritising key attributes and levels based on stakeholder views, including cancer survivors, are key to developing effective DCE surveys [19]. Recent advancements in DCE methodology have encouraged the use of formative qualitative research to assist in development of DCE attributes and studies in this field have been increasing in recent years [19,20,21,22].

This study addresses a gap in the literature relating to shared care options for post-treatment breast cancer follow-up care and aims to develop initial attributes through targeted qualitative research rather than existing evidence. We report the multiple steps toward identifying key attributes from the perspectives of cancer survivors and health care providers for a breast cancer follow-up care model that can be used in a future DCE studies.

2 Methods

A six-stage framework adapted from De Brun et al [11] guided this study process (Fig. 1). The literature review (Stage 1) presents an overview of systematic reviews assessing the effectiveness and implementation of models of post-treatment cancer care, and they informed the remaining stages of the DCE development. This review reported on 53 primary studies, suggesting equivalent effectiveness of shared care and specialist-led models of follow-up care on patient outcomes [6].

adapted from De Brun et al. [11]

Summary of six-step discrete choice experiment (DCE) study methodology,

The current study addresses Stages 2–4 that will then inform the development and delivery of a DCE (Stage 5: Generating the choice set and pilot testing the DCE; and Stage 6: Conducting the DCE). This six-stage study received ethical approval from the University Human Research Ethics Committee (QUT HREC: 4567-HE31), with all participants providing written informed consent prior to participation.

2.1 Focus Groups with Stakeholders to Identify Key Attributes (Stage 2)

The purpose of the focus groups was to identify and explore the attributes of current breast cancer follow-up care models and describe ideal cancer follow-up care services from the perspective of key stakeholders. Focus groups were chosen to encourage discussion around shared lived experiences and enable the generation of information that is unlikely to have been generated in individual interviews [23]. Two categories of participants were included in the focus groups: (1) health service providers (including medical oncologists, radiation oncologists, surgeons, and nurses) involved in breast cancer follow-up care in Australia; and (2) breast cancer survivors aged ≥ 18 years (as healthcare consumers) living in Australia, who are between 6-months and 5-years post-treatment for breast cancer. Purposive sampling was used to recruit participants for maximum variation across geographic locations (e.g., different states and regional or metropolitan locations) as our key delineator decided in advance, as this has considerable influence on what types of care models are available to consumers. The sample size focused on ensuring that each participant had suitable space and time to explore their experiences with cancer follow-up treatment and relate the attributes that they valued in that process, as it was this depth of understanding around attributes that was the focus of our interest. Health service provider participants were identified through the existing professional contacts of the research team who had previously collaborated in cancer survivorship research, and these providers received invitations to participate by email directly from a member of the research team. Breast cancer survivors were recruited through the Breast Cancer Network Australia (BCNA) Review and Survey Group, an established formal request process allowing researchers to place an advertisement in the BCNA newsletter which invited interested research participants to contact the research team via email directly.

Throughout November and December 2021, an experienced qualitative researcher (MA with a background in health service design, implementation, and evaluation) conducted separate online focus groups for each stakeholder group, spanning 90 minutes per session, that enabled participation from locations across Australia. Two other researchers (FCW and RH with backgrounds in cancer care and health economics) took additional notes during the focus groups. The focus group facilitator used a semi-structured interview guide (Supplementary Materials 1a and 1b), with open-ended questions targeting patient perceptions of current and ideal cancer follow-up care, and the associated attributes of those models of care. The focus group guide was flexible, allowing the facilitator to explore relevant themes raised, including how different attributes impact access, service delivery, and perceived success of cancer follow-up care models. The focus group sessions focused on discussing attributes of shared care and specialist-led follow-up care models that would still ensure equivalent clinical patient outcomes. At the end of the focus group sessions, participants reviewed the meeting notes to ensure they were representative of the discussion.

All focus groups were video recorded and transcribed verbatim by a professional transcriber. Data were analysed using a pragmatic rapid analysis technique, which has been shown to have demonstrably comparable effectiveness to traditional methods, such as directed content analysis using a framework [24]. Several iterations of analysis were undertaken using a mixed inductive-deductive approach. Initially one researcher (MA) inductively coded the verbatim transcripts and meeting notes (taken by MA, RH and FCW) and triangulated and summarised the content (including key quotes) into an Excel spreadsheet. During this process some categorisation of codes was conducted with a focus on what codes related to potential attributes of follow-up care models and the varying levels of those attributes, as well as barriers and facilitators experienced. Analysis included reviewing the early inductive codes and categories against the codebook developed from attributes identified in the literature review, to see how and if this prior knowledge could be incorporated into the interpretation of the focus group data, a process consistent with previous DCE attribute development studies [21]. A second researcher (RH) reviewed the analysis while listening to audio recordings and refined and expanded the codes, categories, themes or attributes in the spreadsheet. Once both coders analysed the data, the researchers discussed any differences and developed an initial list of attributes. Some items did not fit as attributes but were included as other considerations (such as barriers) within the themes for discussion, as they were deemed relevant to health care providers and policy makers who design and deliver models of care. We defined an attribute as a feature or characteristic of the health care model (including practices and providers) or the delivery (or receipt) of that service. For example, an attribute for a follow-up care model could be ‘travel distance’, and possible levels could be ‘no travel (telehealth)’, ‘travel up to 50 km’ or ‘travel for more than 50 km’. A survey tool was developed based on the attributes identified from the analysis of the focus group discussions, for use in the prioritisation exercise (Stage 3). What constituted an attribute, as well as wording of the attributes, was reviewed and finalised by four researchers (MA, RH, FCW, SK) as well as a consumer representative (JW) to ensure that plain language was used in the attribute list for ease of comprehension, and to ensure that all the items included for Stage 3 were attributes of a model of care.

2.2 Prioritisation Exercise (Stage 3)

Prioritisation of attributes occurred via quantitative methods to understand which attributes are most important, and to support the selection of a manageable number of attributes for the DCE. Participants who participated in the focus groups were invited to participate in the prioritisation exercise, as well as breast cancer survivors from a previous research study [25] who had expressed an interest in future research. Prioritisation was undertaken through online survey via the Qualtrics platform, commencing with an introduction and consent page, followed by demographic questions. Participants were then asked to review the list of attributes and rank these attributes from ‘most’ (first attribute) to ‘least’ (last attribute) important. The mean score for each attribute was calculated to produce a summary score. Subsequently, the attribute list was sorted in ascending order of the mean score, and the attribute that produced the lowest mean score was determined as the number one attribute from the list. The online survey was open for 6 weeks to enable an adequate response. Three attribute ranking lists were prepared separately for the cancer survivors, clinicians, and combined groups, and formed the basis of the expert panel discussion (Stage 4).

2.3 Expert Panel Discussion to Finalise Attributes and Levels (Stage 4)

An expert panel discussion involving the research team (i.e., experienced cancer clinician-researchers, health economists, and health service researchers) was conducted to further refine the attributes identified in the prioritisation exercise, spanning 90 minutes through video conferencing. An experienced facilitator (MA) guided the expert panel who reviewed results from the prioritisation exercise and undertook a discussion to confer on suitability for the DCE. Experts needed to consider multiple factors, including the input from stakeholders around the relative importance of attributes within the context, relevance to the purpose of the future DCE survey in eliciting patient preferences for different breast cancer follow-up models of care, and attribute relationships to each other [19, 26]. Experts also needed to consider the number of attributes included. Attributes should provide sufficient details to enable choice between the given options and should not place a high cognitive burden on the participants [24]. The majority of DCE studies have used DCE choice tasks with five or six attributes [24]. The inclusion of high numbers of attributes requires complex DCE designs such as overlapping DCE designs. Once the expert panel agreed on attributes to be included in the list, levels and level details needed to make real-world decisions were discussed. A revised set of attributes and levels were circulated to the broader research team members for any additional comments or refinement.

3 Results

3.1 Stage 2: Focus Groups

Four focus groups were held, 2 for clinician stakeholders and 2 for cancer survivor stakeholders, with a total of 15 participants, with demographic characteristics outlined in Table 1.

From the analysis of the focus group transcripts and notes, a total of 16 attributes, along with implementation-related considerations (such as barriers), aligned to 3 main themes (Table 2).

3.1.1 Service Delivery and Accessibility

Several attributes highlighted by participants for inclusion focused on the practical aspects of service delivery, and accessibility to cancer survivors. These attributes considered travel distance, out-of-pocket costs, length of appointment, culturally appropriate services for First Nations cancer survivors, and availability of different appointment delivery options (telehealth and face-to-face).

Significant differences were noted between service delivery and access among regional and remote communities compared with communities in metropolitan settings.

"From my point of view, I'm still, after three years, waiting for reconstruction, but if I lived in Sydney or Melbourne that could have happened at the same time as (my) mastectomy but because I lived in [Northern Australia] I did not have options" Cancer survivor 3

"Mainly all within the rural, regional areas in [Southern state]… the town that I am the [clinician] at the moment… absolutely no other support is free-of-charge for cancer services or any other medical support. So, I tend to do everything...". Healthcare provider 2.

Cancer survivors who had to travel long distances from regional and remote areas highlighted this as a barrier to accessing follow-up care services.

"I live in [regional town] so have had to travel to [regional city] which is […] 64 km away. My husband has to take me, so basically, I have not really been up there, since I finished (treatment). There is a wellness centre up there, which I would have loved to have access to, but because of the distance, and he is aged 84, so you know, so it is a bit of an ask, and he has done really well to take me for treatment." Cancer survivor 4.

"You know there is plenty of information… but access was an issue, particularly being in [Northern Australia], a lot is talked about, but it is just not there. Yes, that would be the same, you know, anywhere rural or remote." Cancer survivor 3.

Participants also articulated the impact of out-of-pocket costs and caps for Medicare (Australian Universal Health Insurance Scheme) on cancer survivors ability to access follow-up care services.

"I was having two lots of injections a month, for about six months last year and then they were free but then earlier this year, they decided to start charging for this, so that is another it was another $80 a month". Cancer survivor 1.

"Lack of (allied health) services… that you can access, they are quite limited… unless there are public ones… (it is) too cost-prohibitive". Healthcare provider 3.

“The other thing with a lot of the issues that women present with […] there's no access to refer them to hospital-based services because (of) the (lack of) funding […] as people get older they have other chronic diseases […] even younger patients, often from lower socioeconomic backgrounds with multiple co-morbidities […] might have seen the psychologist already for other reasons and used their (Medicare covered) visits […] ”. Healthcare provider 6.

Clinicians also highlighted that short appointment times did not allow in-depth conversations that would be beneficial for holistic care, nor the discussion of more sensitive topics around mental health needs, financial needs, or issues around sex and intimacy, that are common after breast cancer.

"We have triple-booked 20-minute appointments so that we have six or seven minutes per patient and we are just focused on symptoms. […] we do not have the facilities or the time, and we are not trained […] we do not get trained in survivorship and wellness”. Healthcare provider 4.

"Obviously, there are other medical treatments and they are quite morbid in themselves, but the women also suffer many social morbidities, sexual morbidity, financial morbidity, you know, like the impacts… are quite multifactorial and in the health system in general, I mean it is, not just for breast cancer, but in health care in general, we tend to focus on sort of medical or physical care without really looking at the whole person". Healthcare provider 3.

3.1.2 Care Coordination

Other attributes agreed for inclusion focused on care coordination including information sharing between clinicians, a designated person to coordinate care, handover, and support for general practitioners (GPs), contact with a cancer nurse throughout the follow-up phase, and use of a multi-disciplinary shared care plan.

Participant experiences highlight that consistent communication and sharing of information between clinicians is not always the case.

"The only thing that has been troubling me is the fact that my GP does not get enough information and he showed me yesterday that when he does, he said it is written like an essay when all he needs is bullet points." Cancer survivor 4

"I have a very good medical oncologist who I see every three to six months, but she rarely sends any documentation to my GP, which I find quite unbelievable, so I am actually the only way my GP knows about what is happening to me, is by me uploading and email(ing) my scanned results to her and my reports." Cancer survivor 5.

However, having a regular GP or a breast care nurse to regularly contact and coordinate care was noted by participants to have a positive impact on access to care and the overall experience.

"Since then, it has only been the regular sort of scans and catch-ups. I have gone between my oncologist and my surgeon and my GP, she is also great like [name of participant] 's GP ... if I have got any issues, I go to her." Cancer survivor 6

“I do think that the key is that coordination. Without having somebody who takes on that coordination role, it is very difficult to keep any sort of survivorship care planning and integration between the acute and general practice or community health teams going (in) any way, shape or form". Healthcare provider 5.

"I mean the people who have been most useful to me, have been, as I said, the breast care nurse, my GP, and my oncologist…in particular I would say it's the fact that (breast care nurse) is available and accessible and highly responsive…I have a mobile number that I can text and I know… getting back to me in 24 hours… or text back saying I am very busy but will get back to you the next two days… makes me know that someone is actually taking me seriously." Cancer survivor 5.

Several barriers to the inclusion of GPs were noted, including a lack of availability, suitability, or willingness of GPs to take on follow-up care in some instances, and limitations to appropriate reimbursement.

"We do not have the space within our cancer system to be doing everything… We need to get patients back to the GPs, but we also need to make sure that the GP has the information and feels comfortable doing it... and I cannot speak for everyone, but some of the GPs I would not trust with the survivorship matters because they would have no idea." Healthcare provider 2

"There is a lot of variation between the ability and willingness of GPs, to take this on. This sort of work can be quite time consuming and emotionally demanding and GPs are not reimbursed for those extra-long consults particularly well." Healthcare provider 3.

“We have people who do not have a regular GP, and this can be an issue if you are looking at transitioning care to primary care.” Healthcare provider 6

Other staffing issues such as turnover were noted to have an adverse impact on care.

“The psychologist I saw was covering my psychologist who was away on maternity leave. I had spent six months with this psychologist she knew me inside out. […]. I fully expected that I would just swap when she came back […]. I went to talk to them and put forward my case and they said “Okay, we will pay for three more appointments with your previous psychologist, but after that, you are on your own. Alternatively, you can start again from scratch with this new person who knows nothing about you […]”. Psychology just does not work that way”. Cancer survivor 3.

3.1.3 Cancer Survivor Support

Other important attributes focused on what support and services were delivered to cancer survivors as part of follow-up care. These included the availability of information provided to cancer survivors on what to expect; the timing of follow-up care discussions, i.e., starting during active treatment and regularly repeated to capture changing cancer survivor needs; the inclusion of allied and mental health services; rapid re-entry process to the hospital or specialist services if issues arise; and the connection to peers and cancer support networks and services.

One consideration related to how cancer survivors felt at the point of transition to follow-up care, which was described on the one hand as a sense of relief around being cancer-free, but negatively as a real sense of loss and disconnection stemming from having intensive interaction with clinical staff in the hospital setting to comparatively limited interaction during follow-up care.

"You've had all this care for all these years and then you have come out at the other end and Yyou think who is going to take care of me now? It's kind of like the system has finished with you and they do not need to see you anymore. I felt like the file had been closed on me." Cancer survivor 2.

"There was certainly that feeling of abandonment after I had completed surgery. I had done five months of chemo and five weeks of radiation, and been at the hospital every single day. When I walked out on the last day it was really strange to go from such intensity and then just bang you're not going to see anyone for ages —it was like they had lost interest in me." Cancer survivor 3.

This feeling of disconnection was often coupled with a lack of information about what the next steps were, including who will be providing what care, what to expect in terms of symptoms, but also practical things like who to call when there is an issue, differences in what each clinician can or will prescribe or refer to, and often a lack of readiness to think about or discuss ongoing wellness and support at the point of transitioning from active treatment to follow-up.

"More information would be good". Cancer survivor 3.

"Everything is happening when you are under treatment, but when the treatment is over and you have a good report, there is a void and you've forgotten what they've told you previously about where to get help. I was feeling so awful from having chemo[…] and they mentioned physio[therapy]— but I can not remember what (the contact information) was". Cancer survivor 4.

As such, shared access to a survivorship care plan, discussions about the length of the follow-up care phase, and repetition of information during follow-up assessments were noted to be important to address the changing needs of cancer survivors.

“Yes, okay so some information, maybe in those early stages, but then again at other intervals as well”. Cancer survivor 4.

“I would like to know what is kind of normal as I recover and what to expect. It is important to have contact – for example: a call to say. ‘Hi, today you are two years' post-treatment, these are some of the things you might be experiencing. These are the people that you can contact’ would be helpful”. Cancer survivor 6

“They have to start from the very beginning because it makes a big difference, it can be a complete mess by the time they get to the end of treatment in terms of their ways and their lifestyle, but also things like the financial security”. Healthcare provider 3

Cancer survivors and clinicians emphasised the importance of including a more holistic range of services including allied health for physical health needs such as exercise and nutrition, psychosocial support for emotional and mental health needs, and practical support from a social worker for things like housing and financial planning. Therefore, this was added as an attribute.

“Just having someone who will sit down and talk to you is incredibly useful[…] not necessarliy a psychologist every time because a lot of the things I’m dealing with is just sadness or worry, I am not clinically depressed. I am just trying to deal with life and living with a post-cancer diagnosis”. Cancer survivor 5.

“Encourage patients to be considering their health, such as exercise and nutrition. Then, most people feel empowered as it is something they can do themselves. I think if we’re able to encourage access to that early on and tell them that this is something that we really see as just as important as their treatment” ". Healthcare provider 1.

There were also socio-cultural barriers to seeking help for many of the breast cancer survivors, including the pressure to be stoic and not complain. Some felt unworthy of support, defer to clinicians as knowing best, and some aren’t comfortable discussing topics such as issues with sex and feeling sexual. There can also be an expectation that they need to accept symptoms as a by-product of cancer treatment, and some participants noted having certain symptoms ignored or minimised by their clinicians.

“It’s very hard to measure wellness and women can be their own worst enemies in that they’re very stoic, they just crack on with life. They may think that their problem is not important enough to the doctor, you know they’ve saved my life, so I should just be grateful to live here in my terribly poor, terribly morbid, terribly unsexual state. People who have been through drugs and alcohol treatment, mental health issue, simply don’t believe that they are worthwhile as women. I mean it relates to a very much larger societal and gender bias, you know, women have to be nice, if we speak up we are being aggressive or bitchy”. Healthcare provider 3

“I'm thinking of relationship difficulties or the weight gain and things like that which we discuss when we are not seeing these women for their regular appointments that potentially they would not otherwise bring up”. Healthcare provider 5

“I think we’re all so fixated on how lucky we are to be alive that sometimes we don’t actually speak up when we need help”. Cancer survivor 5

“I remember when I […] first saw my oncologist, he made a sarcastic comment about how some people think chemo impacts the brain […] but it was like he believed it was imaginary and I'm thinking—really?! I could not drive, I could not make a cup of tea. I could not quite understand the sequence there”. Cancer survivor 6

Participants noted the current system supports those who are proactive and health literate, with others potentially not receiving adequate follow-up support.

“You were very proactive, I was very proactive, but as [consumer representative role] for many years, I will tell you there are many people who are not proactive, and are literally just put out into the cold and have no idea where to go from here”. Cancer survivor 2

3.2 Prioritisation Exercise

Twenty participants (14 cancer survivor and 6 clinicians) completed the prioritisation survey, with their characteristics outlined in Table 1.

Prioritised attributes with their scores are provided in Table 3 and the group-wise prioritisation results are provided in Supplementary Materials 2a and 2b. Clear information for cancer survivors was ranked highly in both cancer survivor and clinician lists. Also ranked highly was the need to start follow-up early and have regular conversations, good information sharing between clinicians, and having a designated person to coordinate follow-up care. Health care providers ranked out-of-pocket costs as number 2, whereas cancer survivors had ranked this attribute as low as 12, despite highlighting this as a key barrier in the focus groups. Further, cancer survivors noted the length of appointment and inclusion of allied health and psychosocial support as being ranked 4th and 5th most important respectively; whilst healthcare providers had these ranked as 14th and 8th most important.

3.3 Expert Panel

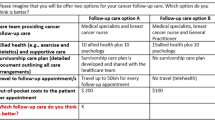

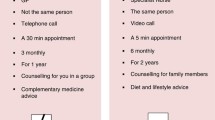

Participants of the expert panel reviewed the prioritised attributes and discussed how different stakeholders prioritised the attributes noting some clear differences between cancer survivors and clinicians and considered the stakeholder ratings in the context of attributes and associated levels of clinical relevance and value to the final DCE survey. The final attribute list determined by the expert panel is provided in Table 4.

Considering several highly rated attributes focused on information sharing between clinicians, and clinicians and cancer survivors; the process of developing and sharing information as well as a survivorship care plan with cancer survivors; and communication and information sharing between clinicians; it was considered these elements could be achieved through the vehicle of a shared care management plan in practice, so this revised attribute was included. The two attributes ‘having a designated person to coordinate care’, and ‘the availability of a cancer care nurse’ were combined into the final attribute ‘care team providing follow-up care’ with choice levels reflecting different follow-up care models that exist in current practice. It was agreed that including access to allied health and mental health services is a key component of providing more holistic person-centred care, which is a key driver of different models of follow-up care. Travel and cost attributes were also included in the final list, despite mixed results in terms of the prioritisation exercise, as the practical aspects of accessibility of follow-up care have been repeatedly highlighted in the literature, and in the personal experience of the clinicians and cancer survivors who participated in the focus groups and the expert panel.

4 Discussion

Five attributes (with 2–3 levels each) were developed for use in a future DCE to elicit cancer survivor preferences on models of follow-up care for breast cancer as presented in Table 4. These attributes cover the practical aspects of service delivery and cancer survivor access to care, care coordination, and the types of support and services included for cancer survivors within different models of care. The developed attributes are broadly consistent with previous research identifying what is most important to breast cancer survivors worldwide [27,28,29,30,31], suggesting the attributes in this study may be applicable in other contexts

Comprehensive follow-up care models with coordination across various health care settings, and including management of psychological, social, and physical health during the post-treatment period for cancer survivors is recommended within the Institute of Medicine report on cancer survivorship [10]. Previous qualitative studies with cancer survivors and clinicians also emphasise that cancer follow-up care should have a more holistic approach than traditional models focusing on recurrences and treatment effects [27,28,29, 31, 32]. For example, from a health care professional point of view, breast cancer follow-up care should include better collaboration between health care professionals, improved communication, and information provision about cancer follow-up care and shared decision making [32]. The findings from these previous studies align with many of the important attributes identified in the present study. A care coordinator is another important attribute of a follow-up care model highlighted by the stakeholders in this study. The cancer survivors in the present study preferred care coordination by their GP or their breast care nurse rather than the specialist. Clinicians also emphasised that quality holistic care would not be possible within the limited time available for each breast cancer survivor during specialist appointments. Although previous evidence has suggested that clinical outcomes are comparable across shared care, nurse-led and specialist-led models [6], the importance of these outcomes for patients need to be considered in future patient preference research.

Previous studies assessing patient preferences of breast cancer follow-up care using the DCE method were conducted around 10 years ago [17, 18] and at that time, reported that the GP was the least preferred provider for breast cancer follow-up care however, models of follow-up cancer care have since evolved. These studies also emphasised that care coordination and cancer survivor preferences with shared-care models between cancer specialists and GPs should be evaluated in future DCE studies [17], such is the purpose of the current study. It is a noteworthy trend that the cancer survivors would like to have shared care between their GP or cancer nurse with their oncology specialist so that they can experience the diverse benefits of care from multiple health care providers, along with more personalised care from their GP, and a referral pathway back to acute care for any disease recurrence, as reported in the present study. However, participants also had concerns about whether the GP had specialised training in cancer follow-up care. Providing specific cancer care training, information, and a structured handover from specialists to the GPs is a key factor in implementing shared care and primary care-led models of cancer survivorship care follow-up [33]. Hence, future research should include GPs to understand potential barriers and enablers, including whether GP education and engagement is needed for effective implementation of shared care models.

Service delivery and accessibility of follow-up breast cancer care are also major concerns raised by the cancer survivors and clinicians in this study. Previous studies also demonstrate that breast cancer survivors in regional and rural areas face more difficulties accessing appropriate care than those in metropolitan areas [30]. In such circumstances, the availability of shared-care management in which cancer survivors can access coordinated care between hospital and primary care settings allows consumers to receive locally available follow-up and allied health services. This can lessen the impact of key barriers to care such as travel distance when seeking specialist care. Further, a shift in the availability of telemedicine (i.e., teleconferencing and online appointments) during the pandemic has positively impacted access to follow-up cancer care services [34]. Availability of these options was noted as a potential attribute in this study, despite face-to-face appointments being the preferred method for follow-up care as evident in the literature [18]. Given the timing of this study, inclusion of telehealth as part of the potential attribute list, is likely due to the shift in attitudes, and an increase in familiarity during the COVID-19 pandemic. Policy decisions around such a model of care using advanced technologies would have to be considered with the developing service delivery models specifically for cancer survivors in rural areas.

4.1 Strengths and Limitations

Strengths of this study include the multiple stages of attribute development including focus groups, prioritisation exercises, expert panel discussions, and refinement. Best practice guidelines for DCE studies recommend using qualitative methods to identify relevant and valid attributes for DCE studies [19, 26], as identifying key attributes is one of the major contributing factors to a successful DCE survey [19]. Previous DCE studies have used qualitative evidence in the literature to derive the attributes for the DCE studies or described the attribute generation phase as a summary [17, 18], which hinders important attributes to be considered, and how the attribute selection was refined. This study provides a detailed description of the process of refining DCE attributes and levels using prioritisation exercises and an expert panel discussion, which has been called for in previous research [11, 19, 35]. Discrete choice experiment attributes that have been developed based on recent qualitative and quantitative studies, and studies designed for this purpose, will be more practical and relevant for use in DCE studies [20,21,22].

Another strength of the present study is the incorporation of feedback from both cancer survivors who experienced breast cancer follow-up care and health care providers to identify attributes for inclusion into the DCE survey. Participants in our study were able to discuss experiencing a range of services in different geographies of Australia, different cancer stages (including metastatic), and treatment pathways (e.g., radiotherapy, chemotherapy, mastectomy/double mastectomy, a combination), and reflections based on their experiences of health care in different countries.

Whilst the focus groups and prioritisation exercise were conducted using an online platform enabling the inclusion of cancer survivors from more locations, we recognise that this may have limited participation from those who are less familiar with technology or with particular disabilities [36]. Another limitation is that we did not collect demographic features such as education or income levels, whether any of our participants identified as Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander peoples, or from culturally or linguistically diverse backgrounds, or were from any other systematically disadvantaged groups, for either the focus group discussion or as part of the prioritisation survey. Future research that focuses on preferences of survivors from diverse backgrounds is required to ensure that shared care models are inclusive of a range of needs and preferences.

Whilst this study was able to include health provider perspectives from a range of disciplines, we were unable to recruit a GP for the focus group or expert panel stages. Input from GPs on potential barriers and enablers to participating in shared care arrangements will be particularly important if the final DCE survey (Stage 6) highlights a preference for their inclusion in future care models.

5 Conclusions

This study identified five main attributes as important attributes of post-treatment breast cancer follow-up care: (1) the care team providing cancer follow-up care; (2) access to allied health, such as exercise and dietetics and supportive care services; (3) survivorship care plan - a detailed document outlining all care arrangements; (4) travel to follow-up appointments, and (5) out-of-pocket costs to the patient per appointment. These attributes will be used in future DCE studies to elicit cancer survivor preferences for breast cancer follow-up care. A patient-centric approach to designing health service delivery models will improve patient satisfaction and support the health care decision-making process to provide optimal health care to cancer survivors. Hence, the findings of this study may lead to the optimal design and implementation of a breast cancer follow-up survivorship care programme that best suits the needs and expectations of breast cancer survivors.

References

Cheng ES, et al. Cancer burden and control in Australia: lessons learnt and challenges remaining. Ann Cancer Epidemiol. 2018;2(3):1–16.

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, BreastScreen Australia monitoring report 2021. AIHW: Canberra; 2021.

Nekhlyudov L, et al. Developing a quality of cancer survivorship care framework: implications for clinical care, research, and policy. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2019;111(11):1120–30.

Arnold M, et al. Progress in cancer survival, mortality, and incidence in seven high-income countries 1995–2014 (ICBP SURVMARK-2): a population-based study. Lancet Oncol. 2019;20(11):1493–505.

Halpern MT, McCabe MS, Burg MA. The cancer survivorship journey: models of care, disparities, barriers, and future directions. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book. 2016;36:231–9.

Chan RJ, et al. Effectiveness and implementation of models of cancer survivorship care: an overview of systematic reviews. J Cancer Surviv. 2021;16:1–25.

Mollica MA, et al. Follow-up care for breast and colorectal cancer across the globe: survey findings from 27 countries. JCO Glob Oncol. 2020;6:1394–411.

Howell D, et al. Models of care for post-treatment follow-up of adult cancer survivors: a systematic review and quality appraisal of the evidence. J Cancer Surviv. 2012;6(4):359–71.

Taylor K, Chan RJ, Monterosso L. Models of survivorship care provision in adult patients with haematological cancer: an integrative literature review. Support Care Cancer. 2015;23(5):1447–58.

Hewitt M, Greenfield S, Stovall E. From cancer patient to cancer survivor: lost in transition. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2005.

De Brun A, et al. A novel design process for selection of attributes for inclusion in discrete choice experiments: case study exploring variation in clinical decision-making about thrombolysis in the treatment of acute ischaemic stroke. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18(1):483.

Ryan M, et al. Use of discrete choice experiments to elicit preferences. Qual Health Care. 2001;10(suppl 1):i55–60.

Kate LM, Mylene L, Kara H. The use of discrete choice experiments to inform health workforce policy: a systematic review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-14-367.

Peacock S, et al. A discrete choice experiment of preferences for genetic counselling among Jewish women seeking cancer genetics services. Br J Cancer. 2006;95(10):1448–53.

Blinman P, et al. Preferences for cancer treatments: an overview of methods and applications in oncology. Ann Oncol. 2012;23:1104–10.

Wong SF, et al. A discrete choice experiment to examine the preferences of patients with cancer and their willingness to pay for different types of health care appointments. JNCCN J Natl Compr Cancer Netw. 2016;14(3):311–9.

Bessen T, et al. What sort of follow-up services would Australian breast cancer survivors prefer if we could no longer offer long-term specialist-based care? A discrete choice experiment. Br J Cancer. 2014;110(4):859–67.

Kimman ML, et al. Follow-up after treatment for breast cancer: one strategy fits all? An investigation of patient preferences using a discrete choice experiment. Acta Oncol. 2010;49(3):328–37.

Coast J, et al. Using qualitative methods for attribute development for discrete choice experiments: issues and recommendations. Health Econ. 2012;21(6):730–41.

Kennedy BL, et al. Factors that patients consider in their choice of non-surgical management for hip and knee osteoarthritis: formative qualitative research for a discrete choice experiment. Patient Patient Centered Outcomes Res. 2022;15(5):537–50.

McCarthy MC, et al. Finding out what matters in decision-making related to genomics and personalized medicine in pediatric oncology: developing attributes to include in a discrete choice experiment. Patient Patient Centered Outcomes Res. 2020;13(3):347–61.

Apantaku G, et al. Understanding attributes that influence physician and caregiver decisions about neurotechnology for pediatric drug-resistant epilepsy: a formative qualitative study to support the development of a discrete choice experiment. Patient Patient Centered Outcomes Res. 2022;15(2):219–32.

Morgan DL. Focus groups as qualitative research, vol. 16. New York: Sage publications; 1996.

Mulhern B, et al. One method, many methodological choices: a structured review of discrete-choice experiments for health state valuation. Pharmacoeconomics. 2019;37:29–43.

Chan RJ, et al. Implementing a nurse-enabled, integrated, shared-care model involving specialists and general practitioners in breast cancer post-treatment follow-up: a study protocol for a phase II randomised controlled trial (the EMINENT trial). Trials. 2020;21(1):855.

Bridges JFP, et al. Conjoint Analysis applications in health—a checklist: a report of the ISPOR good research practices for conjoint analysis task force. Value Health. 2011;14(4):403–13.

Dsouza SM, et al. A qualitative study on experiences and needs of breast cancer survivors in Karnataka, India. Clin Epidemiol Glob Health. 2018;6(2):69–74.

Roorda C, et al. Patients’ preferences for post-treatment breast cancer follow-up in primary care vs. secondary care: a qualitative study. Health Expect. 2015;18(6):2192–201.

DeGuzman PB, et al. Survivorship care plans: rural, low-income breast cancer survivor perspectives. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2017;21(6):692–8.

Lawler S, et al. Follow-up care after breast cancer treatment: experiences and perceptions of service provision and provider interactions in rural Australian women. Support Care Cancer. 2011;19(12):1975–82.

Aunan ST, Wallgren GC, Hansen BS. Breast cancer survivors’ experiences of dealing with information during and after adjuvant treatment: a qualitative study. J Clin Nurs. 2019;28(15–16):3012–20.

Ankersmid JW, et al. Follow-up after breast cancer: variations, best practices, and opportunities for improvement according to health care professionals. Eur J Cancer Care. 2021;30(6): e13505.

Browall M, Forsberg C, Wengstrom Y. Assessing patient outcomes and cost-effectiveness of nurse-led follow-up for women with breast cancer—have relevant and sensitive evaluation measures been used? J Clin Nurs. 2017;26(13–14):1770–86.

Chan RJ, et al. The efficacy, challenges, and facilitators of telemedicine in post-treatment cancer survivorship care: an overview of systematic reviews. Ann Oncol. 2021;32(12):1552–70.

Vass C, Rigby D, Payne K. The role of qualitative research methods in discrete choice experiments. Med Decis Mak. 2017;37(3):298–313.

Carter SM, et al. Conducting qualitative research online: challenges and solutions. Patient Patient Centered Outcomes Res. 2021;14(6):711–8.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank health care providers and cancer survivors for their valuable contributions to the study. Breast cancer survivor participants in this research were recruited from Breast Cancer Network Australia’s (BCNA) Review and Survey Group, a national, online group of Australian women living with breast cancer who are interested in receiving invitations to participate in research. We acknowledge the contribution of the women involved in the Review and Survey Group who participated in this project. We would also like to acknowledge Ms. Jo-Anne Ward for reviewing the study materials and Ms. Carla Shield for reviewing the ethics application.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

The authors declare that no funds, grants, or other support were received during the preparation of this manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Author contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by Michelle Allen, Ruvini Hettiarachchi, Fiona Crawford-Williams and Sanjeewa Kularatna. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Ruvini Hettiarachchi and Michelle Allen and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request and subjected to the approval from the ethics review committee.

Ethics approval

This study was performed in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical approval of this study was granted by the University Human Research Ethics Committee (QUT HREC: 4567-HE31).

Consent to participate

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Consent to publish

Not applicable.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kularatna, S., Allen, M., Hettiarachchi, R.M. et al. Cancer Survivor Preferences for Models of Breast Cancer Follow-Up Care: Selecting Attributes for Inclusion in a Discrete Choice Experiment. Patient 16, 371–383 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40271-023-00631-0

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40271-023-00631-0