Abstract

Introduction

OnabotulinumtoxinA (BT-A) quarterly was the first treatment approved specifically for chronic migraine (CM). It is unclear whether three cycles are better than two to assess early BT-A response.

Methods

We performed a retrospective analysis on real-life prospectively collected data in 16 European headache centers. All the centers provided data on patients treated with BT-A for CM over the first three cycles of treatment. For each treatment cycle we defined patients as “good responders” if reporting a ≥ 50% reduction in monthly headache days compared with the three months before starting BT-A, “partial responders” if reporting a 30–49% reduction in monthly headache days, and “non-responders” if reporting a < 30% reduction in monthly headache days or stopping the treatment before the third cycle.

Results

We included 2879 patients. Seven hundred and eighty-four (64.6%) of the 1213 patients reporting a good response during the first and/or the second cycle had a good response during the third cycle; 309 (49.3%) of the 627 patients reporting a partial response (but no good response) during the first and/or the second cycle had a good response during the third cycle; only 65 (6.3%) of the 1039 patients who did not respond during both the first two cycles achieved a good response during the third cycle. Multivariate analyses showed that partial or good response during the first or the second cycle were independently associated with good response during the third cycle.

Conclusions

Our data suggest that patients with CM responding to BT-A during the first two cycles will likely benefit from the third cycle of treatment, while the probability that non-responders to the first two cycles start responding during the third cycle is low. These results can help guide the individual decision to stop or continue treatment after the second cycle in patients who have not responded to the first two cycles.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Why carry out this study? |

OnabotulinumtoxinA treatment for chronic migraine is very effective in many most patients; however, it is unclear whether the onset of its efficacy should be assessed after two or three cycles. |

We performed a large, retrospective, multicenter study to assess the evolution of response to onabotulinumtoxinA over the first three cycles of treatment. |

What was learned from this study? |

We found that most patients with chronic migraine reporting at least a partial response to any of the first two cycles of onabotulinumtoxinA reported a > 50% decrease in monthly headache days during the third cycle. |

Patients not responding to both the first two cycles are unlikely to respond during the third cycle. |

Digital Features

This article is published with digital features, including a summary slide, to facilitate understanding of the article. To view digital features for this article go to https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.14170229.

Introduction

OnabotulinumtoxinA (BT-A) is the first treatment approved specifically for chronic migraine (CM); its efficacy and safety have been proven in randomized clinical trials [1,2,3,4,5] and confirmed in real-life studies [6,7,8]. The response to BT-A varies in degree of efficacy and time of onset amongst patients. Many patients report a favorable response to BT-A treatment during the first cycle of treatment with BT-A, whereas other patients who do not report any meaningful improvement during the first cycle start responding to the treatment during the second or third cycle. Unfortunately, other patients do not respond even after prolonged treatment [9]. However, despite the wealth of studies assessing the possible predictors of response to BT-A [10,11,12,13,14], none of them have been commonly accepted.

The European Headache Federation (EHF) guidelines for the use of BT-A in CM suggest stopping the treatment in the presence of < 30% reduction in monthly headache days compared to baseline after 2–3 cycles of treatment [15]. However, it is unclear in which patients to stop treatment at the second cycle and in which to proceed with the third one. Furthermore, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) UK guidance for the use of BT-A in CM recommends discontinuing the treatment after two cycles if patients do not reach at least 30% reduction in headache days [16].

The therapeutic dilemma of negative stopping criteria for BT-A treatment has gained importance with the advent of specific therapeutic alternatives for CM, i.e. calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP)-targeted treatments [17, 18]. Besides, patients with CM have surprisingly low persistence to oral preventive treatments, possibly due to their perceived ineffectiveness or to tolerability issues [19, 20]. For those reasons, providing reliable estimates of the onset and the early evolution of response to BT-A might help avoid prolonged ineffective treatment and favor patient compliance.

In order to improve the management of patients with CM who start BT-A treatment, we aimed to provide data to clarify how the clinical response develops and evolves over the first three treatment cycles.

Methods

Inclusion Criteria

We performed a retrospective analysis of prospectively collected data from European centers treating CM with BT-A. All the centers met the following inclusion criteria:

-

1.

Having already performed a real-life prospective data collection on patients with CM, diagnosed according to the International Classification of Headache Disorders (ICHD) criteria, aged ≥ 18 years, treated with BT-A 155–195 units quarterly according to the Phase 3 REsearch Evaluating Migraine Prophylaxis Therapy (PREEMPT) protocol [1]

-

2.

Study approval by the local ethics committees and informed consent obtained from patients, if necessary, according to the local regulations

-

3.

Ability to share a database of collected data

-

4.

Planned follow-up of at least 9 months for all patients, irrespective of treatment discontinuation

Centers were selected following a literature search including the terms “botulinum toxin” and “migraine” or by personal contacts. Pre-selected centers were contacted by e-mail. Nineteen centers were contacted; two centers did not meet the inclusion criteria, while one center declined to participate in the study; 16 centers agreed to participate in the study. Inclusion periods varied across centers and ranged from 2010 to 2020. All centers collected data by using prospective headache diaries.

Ethical Aspects

The present analysis was approved by the Internal Review Board of the University of L’Aquila with protocol number 23/2020. Patients did not have to sign an additional informed consent, as no additional data were required for the present analyses.

Definition of Treatment Response

According to response to BT-A, patients were defined as follows:

-

1.

Good responders patients achieving a ≥ 50% reduction in headache days from baseline—i.e. the 3 months prior to BT-A treatment initiation—to the respective 3-month cycle

-

2.

Partial responders patients achieving a 30–49% reduction in headache days from baseline to the respective 3-month cycle

-

3.

Non-responders patients achieving a < 30% reduction in headache days from baseline to the respective 3-month cycle. The non-responder group also included patients lost to follow-up or discontinuing treatment before the third cycle.

Statistical Analysis

All analyses used the intent-to-treat population, including all patients who started BT-A treatment. As reported earlier, those discontinuing treatment before the third cycle and those lost to follow-up were considered as non-responders. Variables were considered for the analyses, if available, for at least two thirds of patients; no imputation was done for missing data. We performed the main analyses on the whole data set, comparing the characteristics of good responders at the third BT-A cycles with those of partial or non-responders. We then repeated the analyses after excluding patients with partial response during the third BT-A cycle, to better differentiate patient subgroups according to BT-A response. We also performed sensitivity analyses after the exclusion of patients not receiving the third BT-A dose to correct for the effect of negative stopping rules adopted in some centers [16]. No sample size calculation was performed, as the sample size was based on the available data.

We computed the proportions of good responders, partial responders, and non-responders after 3, 6, and 9 months from BT-A treatment initiation. Descriptive statistics were reported as numbers and proportions and means and standard deviations (SDs), as appropriate. We performed univariate comparisons between patients reporting and not reporting a good response to BT-A using the chi-square test or Student’s t test for independent samples, as appropriate. The variables reaching a P value < 0.1 for significance were included in a multinomial stepwise logistic regression model to identify the factors independently associated with response during the third cycle. Two-tailed P for significance was set at < 0.05. Statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS version 20 software.

Results

Baseline Characteristics

During the study period, we included 2879 patients, 81.7% female, with a mean age of 46.6 ± 12.3 years and a mean CM duration of 8.0 ± 8.0 years. Table 1 summarizes the patients’ characteristics at baseline. Table S1 in the electronic supplementary material reports the contribution of each center.

Treatment Response

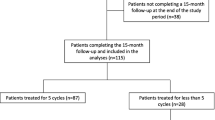

During the first BT-A cycle, 774 (26.9%) patients were good responders, 534 (18.5%) partial responders, and 1571 (54.6%) non-responders (Fig. 1). The proportion of good responders increased through the second (946 good responders; 32.9%; 552 partial responders, 19.2%; 1381 non-responders, 47.9%) and the third cycle (1158 good responders; 40.2%; 337 partial responders, 11.7%; 1384 non-responders, 48.1%; Fig. 1).

Of the 1213 patients reporting a good response during the first and/or the second cycle, 784 (64.6%) reported a good response and 109 (9.0%) a partial response during the third cycle; notably, of the 507 patients who were good responders during both the first and second cycle, 389 (76.7%) maintained the good responder status during the third cycle. A partial response during either the first or the second cycle, without a good response during the first two cycles, was attained by 627 patients, 309 of whom (49.3%) had a good response and 130 (20.7%) a partial response during the third cycle. Only 65 (6.3%) of the 1039 patients maintaining the non-responder status during both the first two cycles achieved a good response during the third cycle, while 98 (9.4%) had a partial response (see Fig. 2).

Predictors of Response

Univariate comparisons showed that good responders during the third cycle had a higher proportion of females (83.5% vs 80.4%; P = 0.020) and medication overuse (78.8% vs 63.3%; P < 0.001), a lower number of monthly headache days (23.5 ± 5.6 vs 24.0 ± 6.2; P < 0.001) and a higher number of monthly medication days (20.8 ± 8.0 vs 18.3 ± 9.6 years; P < 0.001) at baseline compared with partial responders or non-responders; good responders during the third cycle also had a higher proportion of good or partial response during the first two cycles (Table 2). However, after multivariate adjustments, the only factor independently associated with good response during the third cycle was partial or good response during the first or the second cycle (Table 2).

After the exclusion of partial responders at the third cycle, the multivariate analyses showed that medication overuse and partial or good response during the first or the second cycle were independently associated with good response during the third cycle (see Table S2 in the electronic supplementary material).

Sensitivity Analysis

After the exclusion of patients not receiving the third BT-A dose because of a negative stopping rule or physician/patient decision, 2080 patients were left. The proportions of good responders, partial responders, and non-responders were similar to those of the overall group (see Fig. S1 in the electronic supplementary material). Sixty-five (11.5%) of the 565 patients maintaining the non-responder status during both the first two cycles achieved a good response during the third cycle, while 98 (17.3%) had a partial response.

Univariate comparisons showed that good responders during the third cycle had a higher prevalence of medication overuse (78.8% vs 74.2%; P = 0.004) and a higher number of acute medication days (20.8 ± 8.0 vs 19.6 ± 8.9; P = 0.003) compared with the remaining patients (see Table S3 in the electronic supplementary material). Good responders during the third cycle also had a higher proportion of good and partial response during the first two cycles compared with the remaining patients (see Table S3 in the electronic supplementary material). The multivariate analyses also confirmed that good or partial response to BT-A during the second cycle in this subgroup was independently associated with good response during the third cycle, together with younger age (see Table S3 in the electronic supplementary material).

Discussion

In our study, a good or at least partial response during the first two BT-A cycles was consistently associated with a good response during the third cycle across the main and several sensitivity analyses. Our study focused on the first three cycles of BT-A treatment, as it aimed to provide guidance for the decision of whether to continue or to stop the treatment after the second cycle, according to the initial response. Our data suggest that (1) patients showing early response to BT-A tend to maintain their response; (2) a relevant proportion of patients showing even partial response to BT-A during the first two cycles of treatment will become good responders during the third cycle; and 3) the probability of good clinical response to BT-A is lower in patients not responding during both the first two cycles.

The added value of the present study is providing the detail of response to BT-A during each cycle (Fig. 1), considering patients who developed a new-onset response and patients who lost their response over time. This was possible because of the large number of included patients selected from international real-life practice; all patients would have fulfilled the recently issued definition of “resistant migraine” [21]. As investigators were not aware of the study aim a priori, we can exclude any influence on treatment disposition according to personal expectations. On the other hand, we have to consider that regulations and physician attitude have implications for the results. In some countries and in some centers, because of regulatory constraints [8, 16, 22] (< 30% decrease in headache days according to the English, < 50% according to the Australian criteria) or personal beliefs, physicians discontinued treatment in non-responders after the second cycle. This may have led to an underestimation of the benefit of BT-A in non-responders. To control for that potential bias, we repeated the analyses excluding patients who did not receive the third BT-A dose because of a negative stopping rule or physician/patient decision; those sensitivity analyses still showed that partial or good response during the second BT-A cycle can help in predicting response during the third cycle.

In our study, the proportion of patients reporting a ≥ 50% reduction in monthly headache days compared with baseline, i.e. “good responders,” was lower (26.9%, 32.9%, and 40.2% during the first, second, and third BT-A cycle, respectively) as compared with those of the PREEMPT trials, in which 49.0% of patients had a ≥ 50% response during the first cycle [23]. This difference might be due to the difference in study design and setting, as real-life patients have a higher disease burden than the highly selected patients included in clinical trials. Similarly to the available trials, in our population the proportion of good responders increased during the first three cycles (Fig. 1). Together with good responders, our study also considered “partial responders,” reporting a 30–49% reduction in monthly headache days compared with baseline. In fact, a 30% decrease in monthly headache days was suggested to be acceptable in some patients with CM [24, 25]. Our study suggests that the condition of partial responder to BT-A is relevant, as it may predict the future condition of good responder.

It is worth mentioning that our definition of the responder status was based only on the decrease in monthly headache days compared with baseline. The efficacy assessment of CM treatments should consider not only headache days, but also migraine days, moderate/severe headache days, medication use, conversion from CM to episodic migraine, termination of medication overuse, and patient-reported outcomes and scales. These outcomes are suggested by guidelines and reported by real-life studies [15, 26,27,28].

A further point which needs to be considered is that we focused on the first three BT-A cycles. Evidence suggests that about one quarter of patients treated with BT-A who develop a response to the drug within the first two cycles might lose their response during the fourth cycle, while a comparable proportion of patients develop a new-onset response to BT-A during the third or fourth cycle [29]. Response to BT-A may fluctuate over time, and not all responders show a sustained response to the drug [29, 30]. Fluctuations in response to BT-A might be common in the long term if we consider each single patient.

Our data have further limitations. Although the data were collected prospectively, the study had a retrospective design, leading to heterogeneity of data collection across centers. We minimized the collected data in order to limit missing information and inaccuracy. We recognize that important information, such as the presence of cutaneous allodynia and the number of prior preventive treatment failures, was not available from most centers. For the same reason, we could not consider the effect of BT-A dosage, which is likely higher with increasing BT-A doses [31]. A further study limitation is represented by the heterogeneity in the quantitative contribution of different centers (see Table S1 in the electronic supplementary material); large centers might have had a greater impact on the study than the smaller ones. We also did not distinguish migraine days from headache days, which could have added further detail to outcome assessment. Furthermore, we could not distinguish patients discontinuing BT-A because of ineffectiveness from those who discontinued because of noncompliance.

Implications for Clinical Practice in the New Treatment Era

Our findings suggest that it is not reasonable to discontinue the treatment with BT-A after only one cycle, otherwise a relevant proportion of patients may miss a valid therapeutic opportunity; in our study, 532 (33.8%) of the 1571 non-responders during the first cycle achieved a good or partial response during the second cycle, while 590 (37.6%) achieved a good or partial response during the third cycle. Considering the findings of this study, continuing BT-A treatment is advisable in patients reporting even a partial response within the second cycle, while stopping treatment might be considered in patients who are non-responders during the first two treatment cycles, because the probability of a later response is low. Our data can help in establishing clearer rules for BT-A discontinuation, which according to current guidelines, is reasonable if the patient “does not respond” to the first “2–3” treatment cycles [15]. Our data suggest that we should wait for a 30% reduction in monthly headache days over the first two treatment cycles to determine the efficacy of BT-A. Many patients with CM continue treatment with BT-A because of a decrease in headache duration and/or intensity, even in the absence of a decrease in monthly headache days, as they still perceive a benefit. This aspect of BT-A benefit is usually assessed by patient-reported outcomes, such as standardized scales, for which the present study does not provide enough data.

The possibility of early treatment switch from BT-A is important, given the long duration (3 months) of a treatment cycle. Establishing criteria for early treatment change from BT-A is of increasing importance in light of the rise in CGRP-targeted treatments to treat CM [18, 32]; the new BT-A treatment algorithms should include the possibility of early switch to other effective agents [28]. The evidence on the combination of BT-A with CGRP-targeted treatment is only preliminary [33, 34], and some European regulatory authorities prohibit such a combination. If CGRP-targeted treatments can be offered to patients with insufficient response to BT-A, stopping BT-A as early as after the first two cycles and switching to a CGRP-targeted treatment might be a viable option. In contrast, if a patient starts BT-A treatment after failing CGRP-targeted treatments, it might be reasonable to prolong the treatment for more than 3–4 cycles before addressing the clinical response, especially if the patients have already tried the other available preventive options. Future personalized approaches to treatment, including pharmacogenetics [35, 36], will likely provide an objective basis for the prediction of response to BT-A as well as to other migraine preventive treatments.

Conclusion

According to our data, the first two treatment cycles of BT-A can help determine the response to the drug during the third cycle in patients with CM. Patients reporting at least a 30% decrease in monthly headache days within the first two cycles compared with baseline are likely to respond to the third cycle of BT-A. Conversely, patients not reporting at least a partial response to the first two cycles are unlikely to respond to the subsequent cycle and might be considered for treatment discontinuation. Our data are limited by the small number of outcomes assessed; therefore, they cannot constitute a guideline and cannot replace clinical judgment. Nevertheless, we think that our study can help inform clinical practice.

References

Aurora SK, Dodick DW, Turkel CC, DeGryse RE, Silberstein SD, Lipton RB, et al. OnabotulinumtoxinA for treatment of chronic migraine: results from the double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled phase of the PREEMPT 1 trial. Cephalalgia. 2010;30(7):793–803. https://doi.org/10.1177/0333102410364676.

Aurora SK, Winner P, Freeman MC, Spierings EL, Heiring JO, DeGryse RE, et al. OnabotulinumtoxinA for treatment of chronic migraine: pooled analyses of the 56-week PREEMPT clinical program. Headache. 2011;51(9):1358–73. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1526-4610.2011.01990.x.

Aurora SK, Dodick DW, Diener HC, DeGryse RE, Turkel CC, Lipton RB, et al. OnabotulinumtoxinA for chronic migraine: efficacy, safety, and tolerability in patients who received all five treatment cycles in the PREEMPT clinical program. Acta Neurol Scand. 2014;129(1):61–70. https://doi.org/10.1111/ane.12171.

Diener HC, Dodick DW, Aurora SK, Turkel CC, DeGryse RE, Lipton RB, et al. OnabotulinumtoxinA for treatment of chronic migraine: results from the double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled phase of the PREEMPT 2 trial. Cephalalgia. 2010;30(7):804–14. https://doi.org/10.1177/0333102410364677.

Dodick DW, Turkel CC, DeGryse RE, Aurora SK, Silberstein SD, Lipton RB, et al. OnabotulinumtoxinA for treatment of chronic migraine: pooled results from the double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled phases of the PREEMPT clinical program. Headache. 2010;50(6):921–36. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1526-4610.2010.01678.x.

Blumenfeld AM, Stark RJ, Freeman MC, Orejudos A, Manack AA. Long-term study of the efficacy and safety of OnabotulinumtoxinA for the prevention of chronic migraine: COMPEL study. J Headache Pain. 2018;19(1):13. https://doi.org/10.1186/s10194-018-0840-8.

Ahmed F, Gaul C, García-Moncó JC, Sommer K, Martelletti P, Investigators RP. An open-label prospective study of the real-life use of onabotulinumtoxinA for the treatment of chronic migraine: the REPOSE study. J Headache Pain. 2019;20(1):26. https://doi.org/10.1186/s10194-019-0976-1.

Andreou AP, Trimboli M, Al-Kaisy A, Murphy M, Palmisani S, Fenech C, et al. Prospective real-world analysis of OnabotulinumtoxinA in chronic migraine post-National Institute for Health and Care Excellence UK technology appraisal. Eur J Neurol. 2018;25(8):1069-e83. https://doi.org/10.1111/ene.13657.

Sarchielli P, Romoli M, Corbelli I, Bernetti L, Verzina A, Brahimi E, et al. Stopping onabotulinum treatment after the first two cycles might not be justified: results of a real-life monocentric prospective study in chronic migraine. Front Neurol. 2017;8:655. https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2017.00655.

Alpuente A, Gallardo VJ, Torres-Ferrus M, Alvarez-Sabin J, Pozo-Rosich P. Early efficacy and late gain in chronic and high-frequency episodic migraine with onabotulinumtoxinA. Eur J Neurol. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1111/ene.14028.

Alpuente A, Gallardo VJ, Torres-Ferrús M, Álvarez-Sabin J, Pozo-Rosich P. Short and mid-term predictors of response to onabotulinumtoxina: real-life experience observational study. Headache. 2020;60(4):677–85. https://doi.org/10.1111/head.13765.

di Cola SF, Caratozzolo S, Liberini P, Rao R, Padovani A. Response predictors in chronic migraine: medication overuse and depressive symptoms negatively impact onabotulinumtoxin-A treatment. Front Neurol. 2019;10:678. https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2019.00678.

Cernuda-Morollón E, Ramón C, Larrosa D, Alvarez R, Riesco N, Pascual J. Long-term experience with onabotulinumtoxinA in the treatment of chronic migraine: what happens after one year? Cephalalgia. 2015;35(10):864–8. https://doi.org/10.1177/0333102414561873.

Domínguez C, Pozo-Rosich P, Torres-Ferrús M, Hernández-Beltrán N, Jurado-Cobo C, González-Oria C, et al. OnabotulinumtoxinA in chronic migraine: predictors of response. A prospective multicentre descriptive study. Eur J Neurol. 2018;25(2):411–6. https://doi.org/10.1111/ene.13523.

Bendtsen L, Sacco S, Ashina M, Mitsikostas D, Ahmed F, Pozo-Rosich P, et al. Guideline on the use of onabotulinumtoxinA in chronic migraine: a consensus statement from the European Headache Federation. J Headache Pain. 2018;19(1):91. https://doi.org/10.1186/s10194-018-0921-8.

(NICE) NIfCE: Botulinum toxin type A for the prevention of headaches in adults with chronic migraine. In.; 2012.

Tiseo C, Ornello R, Pistoia F, Sacco S. How to integrate monoclonal antibodies targeting the calcitonin gene-related peptide or its receptor in daily clinical practice. J Headache Pain. 2019;20(1):49. https://doi.org/10.1186/s10194-019-1000-5.

De Matteis E, Guglielmetti M, Ornello R, Spuntarelli V, Martelletti P, Sacco S. Targeting CGRP for migraine treatment: mechanisms, antibodies, small molecules, perspectives. Expert Rev Neurother. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1080/14737175.2020.1772758.

Hepp Z, Dodick DW, Varon SF, Gillard P, Hansen RN, Devine EB. Adherence to oral migraine-preventive medications among patients with chronic migraine. Cephalalgia. 2015;35(6):478–88. https://doi.org/10.1177/0333102414547138.

Hepp Z, Dodick DW, Varon SF, Chia J, Matthew N, Gillard P, et al. Persistence and switching patterns of oral migraine prophylactic medications among patients with chronic migraine: A retrospective claims analysis. Cephalalgia. 2017;37(5):470–85. https://doi.org/10.1177/0333102416678382.

Sacco S, Braschinsky M, Ducros A, Lampl C, Little P, van den Brink AM, et al. European headache federation consensus on the definition of resistant and refractory migraine: developed with the endorsement of the European Migraine & Headache Alliance (EMHA). J Headache Pain. 2020;21(1):76. https://doi.org/10.1186/s10194-020-01130-5.

Stark C, Stark R, Limberg N, Rodrigues J, Cordato D, Schwartz R, et al. Real-world effectiveness of onabotulinumtoxinA treatment for the prevention of headaches in adults with chronic migraine in Australia: a retrospective study. J Headache Pain. 2019;20(1):81. https://doi.org/10.1186/s10194-019-1030-z.

Silberstein SD, Dodick DW, Aurora SK, Diener HC, DeGryse RE, Lipton RB, et al. Per cent of patients with chronic migraine who responded per onabotulinumtoxinA treatment cycle: PREEMPT. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2015;86(9):996–1001. https://doi.org/10.1136/jnnp-2013-307149.

Khalil M, Zafar HW, Quarshie V, Ahmed F. Prospective analysis of the use of OnabotulinumtoxinA (BOTOX) in the treatment of chronic migraine; real-life data in 254 patients from Hull, U.K. J Headache Pain. 2014;15:54. https://doi.org/10.1186/1129-2377-15-54.

Ruscheweyh R, Förderreuther S, Gaul C, Gendolla A, Holle-Lee D, Jürgens T, et al. Treatment of chronic migraine with botulinum neurotoxin A: Expert recommendations of the German Migraine and Headache Society. Nervenarzt. 2018;89(12):1355–64. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00115-018-0534-0.

Tassorelli C, Diener HC, Dodick DW, Silberstein SD, Lipton RB, Ashina M, et al. Guidelines of the International Headache Society for controlled trials of preventive treatment of chronic migraine in adults. Cephalalgia. 2018;38(5):815–32. https://doi.org/10.1177/0333102418758283.

Tassorelli C, Tedeschi G, Sarchielli P, Pini LA, Grazzi L, Geppetti P, et al. Optimizing the long-term management of chronic migraine with onabotulinumtoxinA in real life. Expert Rev Neurother. 2018;18(2):167–76. https://doi.org/10.1080/14737175.2018.1419867.

Sacco S, Russo A, Geppetti P, Grazzi L, Negro A, Tassorelli C, et al. What is changing in chronic migraine treatment? An algorithm for onabotulinumtoxinA treatment by the Italian chronic migraine group. Expert Rev Neurother. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1080/14737175.2020.1825077.

Vernieri F, Paolucci M, Altamura C, Pasqualetti P, Mastrangelo V, Pierangeli G, et al. Onabotulinumtoxin-A in chronic migraine: should timing and definition of non-responder status be revised? suggestions from a real-life Italian multicenter experience. Headache. 2019;59(8):1300–9. https://doi.org/10.1111/head.13617.

Ornello R, Guerzoni S, Baraldi C, Evangelista L, Frattale I, Marini C, et al. Sustained response to onabotulinumtoxin A in patients with chronic migraine: real-life data. J Headache Pain. 2020;21(1):40. https://doi.org/10.1186/s10194-020-01113-6.

Negro A, Curto M, Lionetto L, Martelletti P. A two years open-label prospective study of OnabotulinumtoxinA 195 U in medication overuse headache: a real-world experience. J Headache Pain. 2015;17:1. https://doi.org/10.1186/s10194-016-0591-3.

Sacco S, Bendtsen L, Ashina M, Reuter U, Terwindt G, Mitsikostas DD, et al. European headache federation guideline on the use of monoclonal antibodies acting on the calcitonin gene related peptide or its receptor for migraine prevention. J Headache Pain. 2019;20(1):6. https://doi.org/10.1186/s10194-018-0955-y.

Armanious M, Khalil N, Lu Y, Jimenez-Sanders R. Erenumab and ONABOTULINUMTOXINA combination therapy for the prevention of intractable chronic migraine without aura: a retrospective analysis. J Pain Palliat Care Pharmacother. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1080/15360288.2020.1829249.

Martelletti P. Combination therapy in migraine: asset or issue? Expert Rev Neurother. 2020;20(10):995–6. https://doi.org/10.1080/14737175.2020.1821655.

Borro M, Guglielmetti M, Simmaco M, Martelletti P, Gentile G. The future of pharmacogenetics in the treatment of migraine. Pharmacogenomics. 2019;20(16):1159–73. https://doi.org/10.2217/pgs-2019-0069.

Pomes LM, Guglielmetti M, Bertamino E, Simmaco M, Borro M, Martelletti P. Optimising migraine treatment: from drug-drug interactions to personalized medicine. J Headache Pain. 2019;20(1):56. https://doi.org/10.1186/s10194-019-1010-3.

Acknowledgements

Funding

No funding or sponsorship was received for this study or publication of this article.

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Medical Writing, Editorial, and Other Assistance

The Authors wish to thank Víctor José Gallardo López from the Vall d’Hebron Institute of Research (VHIR), Barcelona, Spain, for statistical advice.

Prior Presentation

Preliminary results of the present work were presented in poster form at the 34th congress of the Italian Society for the Study of Headaches (SISC), virtual edition, 23–26 September, 2020, and at the 51st congress of the Italian Neurological Society (SIN), virtual edition, 20–30 November, 2020.

Disclosures

Raffaele Ornello reports speaker fees from Novartis and Eli Lilly, travel grants from Teva, and support for publication from Novartis and Allergan. Simona Sacco reports personal fees from Allergan-AbbVie, AstraZeneca, Abbott, Teva, Novartis, and Eli Lilly. Alicia Alpuente has received honoraria for educational projects from Allergan-Abbvie, Novartis, and Teva. Patricia Pozo-Rosich has received honoraria as a consultant and speaker for Allergan-Abbvie, Almirall, Amgen, Biohaven, Chiesi, Eli Lilly, Medscape, Neurodiem, Novartis, and Teva; her research group has received research grants from Allergan, and has received funding for clinical trials from Alder, Allergan-Abbvie, electroCore, Eli Lilly, Novartis, and Teva; she is a trustee member of the board of the International Headache Society, member of the Council of the European Headache Society; she is on the editorial board of Revista de Neurologia, associate editor of Cephalalgia, Headache, Neurologia, and Frontiers in Neurology, and advisor for The Journal of Headache and Pain; she is a member of the Clinical Trials Standing Committee of the International Headache Society; she has edited the Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Headache of the Spanish Neurological Society; she is the founder of www.midolordecabeza.org; she does not own stocks from any pharmaceutical company. Andrea Negro has received speaking honoraria and has served on the advisory boards of Allergan, Eli Lilly and Company, and Novartis. Paolo Martelletti has received speaker’s honoraria and has served on the advisory boards of Allergan, Eli Lilly and Company, Novartis, and Teva Pharmaceuticals; he is also an EMA Expert and has served as Editor-in-Chief of The Journal of Headache and Pain and as Editor-in-Chief of SN Comprehensive Clinical Medicine; he also declares royalties received from Springer Nature. Massimo Filippi is Editor-in-Chief of the Journal of Neurology and Associate Editor of Neurological Sciences; received compensation for consulting services and/or speaking activity from Bayer, Biogen Idec, Merck Serono, Novartis, Roche, Sanofi Genzyme, Takeda, and Teva Pharmaceutical Industries; and receives research support from Biogen Idec, Merck Serono, Novartis, Teva Pharmaceutical Industries, Roche, Italian Ministry of Health, Fondazione Italiana Sclerosi Multipla, and ARiSLA (Fondazione Italiana di Ricerca per la SLA). Elena Filatova reports speaker fees from Novartis and Teva. Nina Latysheva reports speaker fees from Novartis and Allergan. Carlo Baraldi has received travel grants and honoraria from Allergan, Novartis, Teva, and Ely Lilly. Licia Grazzi has received consultancy and advisory fees from Allergan, electroCore LLC, Novartis, and Eli Lilly, and collaborates in trials sponsored by Eli Lilly, Teva, and PharmInd. Simona Guerzoni has received travel grants and honoraria from Allergan, Eli Lilly, Teva, and Novartis. Sabina Cevoli has received honoraria as speaker, for participating on advisory boards, or for clinical investigation studies from Teva, Allergan, Novartis, Lilly, and Ibsa. Fayyaz Ahmed has received honorarium from Allergan for being on their advisory board and is paid to the charitable organizations. Giorgio Lambru has received speaker honoraria and funding for travel, and has received honoraria for participation on advisory boards sponsored by Allergan, Novartis, Eli Lilly, and Teva; he has also received speaker honoraria and funding for travel from electroCore, Nevro Corp., and Autonomic Technologies. Anna P. Andreou has received speaker honoraria and funding for travel from Allergan, Eli Lilly, and eNeura, honoraria for participation on advisory boards sponsored by Allergan and Eli Lilly, sponsorship for educational purposes from eNeura, Allergan, Autonomic Technologies, and Novartis, and an equipment grant from eNeura. Antonio Russo has received speaker honoraria from Allergan, Lilly, Novartis, and Teva, and serves as an associate editor of Frontiers in Neurology (Headache Medicine and Facial Pain session). Marcello Silvestro has received speaker honoraria from Lilly, Novartis, and Teva. Ruth Ruscheweyh has received travel grants and/or honoraria from Allergan, Hormosan, Lilly, Novartis, and Teva. Fabrizio Vernieri has received travel grants, honoraria for advisory boards, and speaker panels from Allergan, Angelini, Lilly, Novartis, and Teva. Marcin Straburzynski has received personal fees from Novartis and Teva. Katharina Kamm has received travel grants and/ or honoraria from Lilly, Novartis, and Teva. Paola Torelli has received travel grants and/or honoraria from Allergan, Lilly, Novartis, and Teva. Anna Gryglas-Dworak has received honoraria as a speaker and travel grants from Allergan and honoraria as a speaker from Novartis. Ilaria Frattale, Anna Maria Miscio, Antonio Santoro, Nicoletta Brunelli, Bruno Colombo, Calogera Butera, and Marco Russo declare no conflicts of interest.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

The present analysis was approved by the Internal Review Board of the University of L’Aquila with protocol number 23/2020. Patients did not have to sign an additional informed consent as no additional data were required for the present analyses.

Data Availability

The data sets analyzed during the current study are available from the participant centers upon reasonable request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ornello, R., Ahmed, F., Negro, A. et al. Early Management of OnabotulinumtoxinA Treatment in Chronic Migraine: Insights from a Real-Life European Multicenter Study. Pain Ther 10, 637–650 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40122-021-00253-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40122-021-00253-0