Abstract

Introduction

As life expectancy increases for lung cancer patients with bone metastases, the need for personalized local treatment to reduce pain is expanding.

Methods

Patients were treated by a multidisciplinary team (MDT), and local treatment including surgery, percutaneous osteoplasty, or radiation. Visual analog scale (VAS) and quality of life (QoL) scores were analyzed. VAS at 12 weeks after treatment was the main outcome. We developed and tested machine learning models to predict which patients should receive local treatment. Model discrimination was evaluated by the area under curve (AUC), and the best model was used for prospective decision-making accuracy validation.

Results

Under the direction of MDT, 161 patients in the training set, 32 patients in the test set, and 36 patients in the validation set underwent local treatment. VAS in surgery, percutaneous osteoplasty, and radiation groups decreased significantly to 4.78 ± 1.28, 4.37 ± 1.36, and 5.39 ± 1.31 at 12 weeks, respectively (p < 0.05), with no significant differences among the three datasets, and improved QoL was also observed (p < 0.05). A decision tree (DT) model that included VAS, bone metastases character, Frankel classification, Mirels score, age, driver gene, aldehyde dehydrogenase 2, and enolase 1 expression had a best AUC in predicting whether patients would receive local treatment of 0.92 (95% CI 0.89–0.94) in the training set, 0.85 (95% CI 0.77–0.94) in the test set, and 0.88 (95% CI 0.81–0.96) in the validation set.

Conclusion

Local treatment provided significant pain relief and improved QoL. There were no significant differences in reducing pain and improving QoL among training, test, and validation sets. The DT model was best at determining whether patients should receive local treatment. Our machine learning model can help guide clinicians to make local treatment decisions to reduce pain.

Trial registration

Trial registration number ChiCRT-ROC-16009501.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Why carry out this study? |

Local treatment for lung cancer patients with bone metastases must be individually tailored to each patient with consideration for multiple factors. |

What was learned from the study? |

Local treatment performed by multidisciplinary team could provide significant pain relief. |

A decision tree model had the best AUC in predicting whether patients would receive local treatment. |

There were no significant differences in reducing pain among training, test, and validation sets. |

Machine learning algorithms can help guide local treatment decisions to reduce pain in clinical use. |

Digital Features

This article is published with digital features, including a summary slide, to facilitate understanding of the article. To view digital features for this article go to https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.14095903.

Introduction

Bone metastases develop in 36% of patients with advanced lung cancers [1]. Bone metastases can lead to skeletal-related events (SREs) such as severe pain, pathologic fracture (PF), spinal cord compression (SCC), required radiation, bone surgery, and hypercalcemia [2], thereby significantly reducing the quality of life (QoL) of patients with lung cancer [3].

Although systemic medical treatments can control lung tumor growth [2], they are not sufficient to reduce pain, restore the integrity of bones, and allow a return to light weight-bearing [4]. Recent progression in lung cancer treatments, such as development of molecular-targeted agents, has improved patient survival [5]. With increasing life expectancy, there is growing need for effective local treatment for bone metastases to reduce pain and improve QoL. Surgery can restore the integrity of bones, but the decision of whether to perform surgery can be difficult, as the risks may outweigh benefits of pain reduction and improved function [6]. Alternatively, percutaneous osteoplasty (POP) is an effective and safe palliative therapy to reduce pain and improve QoL [7]. Further, radiation can improve reduced QoL caused by painful bone metastases [8]. In addition, previous work has emphasized the requirement of a multidisciplinary team (MDT) approach involving a team of specialists in oncology to reduce pain and improve patients’ QoL [9].

Local treatment indications have been controversial, and local treatment for lung cancer patients with bone metastases must be individually tailored to each patient with consideration for multiple factors. As there is increasing need for automatic and accurate analysis for clinical use, machine learning offers a solution to generate reasonable generalizations, discover patterns, and enable more accurate decision-making [10]. Machine learning may facilitate more effective assessments by physicians [11]. We previously built machine learning models to predict SREs risk [12]. The purpose of this study was (1) to evaluate the feasibility and effectiveness of applying our local treatment algorithm to reduce chronic pain and improve patients’ QoL, and (2) to develop and validate machine learning models for local treatment decision-making to reduce pain in lung cancer patients with bone metastases.

Methods

Patient Selection

This study was approved by the ethics committee of Shanghai Sixth People’s Hospital Affiliated to Shanghai Jiaotong University in October 20, 2016 and was registered in the Chinese Clinical Trial Registry (No. ChiCRT-ROC-16009501) in October 20, 2016. Principles of the Declaration of Helsinki were followed. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants in this study.

Inclusion criteria were: (1) age over 18 years, (2) pathology-proven diagnosis of lung cancer and radiographical/pathological evidence of bone metastases, (3) no previous treatment for bone metastases, and (4) good general condition, as measured by Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance scores of 0–2 with an estimated survival time of more than 3 months.

Management Algorithm

Indications for systemic treatments, including chemotherapy, target therapy, and bone-targeting agents (BTAs), as well as local treatment, including surgery, POP, and radiation, were evaluated by an MDT of medical oncologists, radiation oncologists, interventional radiologists, orthopedic oncologists, and pain specialists. The algorithm is shown in Fig. 1.

Spinal stability was ascertained using Spinal Instability Neoplastic Scores (SINS) [13], and the risk of pathological fracture for the appendicular skeleton was ascertained using the Mirels scoring system [14]. Surgical procedures followed guidelines of the Global Spine Tumor Study Group and Italian Orthopedic Society [15,16,17,18]. Procedures for POP were introduced by our MDT in 2012 [7]. Radiation was performed mainly with 6-MV photons using linear accelerators. Dose fractionation schedules included multi-fraction radiation, such as 30 Gy in ten fractions. Adjuvant therapy-like radiation [19] was used after surgery or POP to prevent tumor recurrence.

Informed consent was obtained for all patients in the study. If local treatment was performed, informed consent by the patient or a legal guardian was obtained 24 h before initiation and after thorough explanation of the methods, potential complications, and alternative treatments.

Data Collection and Follow-up

Medical records were reviewed to collect clinical data. The driver gene of lung cancer (primary lung tissue or bone metastases tissue) and five differentially expressed proteins of bone metastases (bone metastases tissue)—enolase 1 (ENO1), ribosomal protein lateral stalk subunit P2 (RPLP2), calcyphosine (CAPS1), NME/NM23 nucleoside diphosphate kinase 2 (NME1–NME2), and aldehyde dehydrogenase 2 (ALDH2) [20]—were also collected.

Patients were asked to complete a questionnaire that assessed severity of pain using the mean daily visual analog scale (VAS) [21] and QoL using the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire Bone Metastases Module (EORTC QLQ-BM22) [22, 23] 1 day before and at 1, 6, 12, and 24 weeks after local treatment or enrollment. VAS at 12 weeks was the main outcome. Patients were followed for survival every 3 months.

Cost Valuation

Cost analyses of individual patients were estimated from a payer perspective using health resource utilization data from patient charts. Costs of procedures performed during an inpatient stay were assumed to be captured in diagnosis-related group costs.

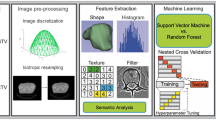

Model Development

Decision trees (DT) (eXtreme Gradient Boosting, XGBoots), support vector machine (SVM), and Bayesian neural networks (BNN) were used to build local treatment decision-making models. On the basis of our previous research [12], we selected the following predictor variables: sex, age, ECOG, VAS, bone metastases character, extent of bone metastases, visceral metastases, Frankel classification, and Mirels scale. As additional predictor variables, we selected lung cancer pathology, lung cancer driver gene, and five differentially expressed bone metastasis proteins. The model output was 0, no local treatment; or 1, local treatment. The training set including patients who had improved VAS and QoL measures after local treatment.

Model Performance

In the training set, we used tenfold cross validation. The test set consisted of data not associated with the training set. Model discrimination was evaluated by area under the receiver operator characteristic curves (AUC). Sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy were used to evaluate model performance.

Model Validation

The validation subset was used to prospectively evaluate the accuracy of DT models in predicting whether patients would receive local treatment. DT models made the decision whether to take local treatment or not. The MDT made the final decision about which local treatment to provide to patients and could reject the model’s decision. Compared with MDT, the AUC, sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy were used to evaluate model performance.

Statistical Analysis

Stata Corp 2013 (Stata Statistical Software: Release 13; StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA) and Python Version 3.6 (Python Software Foundation, Wilmington, DE, USA) were used to analyze data and build the model. Median values and ranges were determined for descriptive statistics. Chi-square and Fisher’s exact tests were used for categorical variables. Student’s t tests and Mann–Whitney tests were used for continuous and ordinal variables. Wilcoxon signed-rank tests were used to compare paired outcomes at various follow-up times. The Kaplan–Meier method was used to estimate survival. A p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics

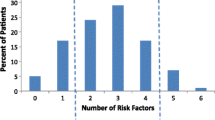

We enrolled 746 patients: the training set included 513 patients enrolled from October 24, 2016 to June 30, 2018; the test set included 108 patients enrolled from July 1, 2018 to October 31, 2018; and the validation set included 125 patients enrolled from November 1, 2018 to February 25, 2019. Of these, 161 patients in the training set, 32 patients in the test set, and 36 patients in the validation set underwent local treatment. A flow chart of the study is shown in Fig. 2a. Patient demographics and clinical characteristics did not significantly differ among the three datasets as shown in Table 1. Treatments in training, test, and validation sets are shown in Fig. 2b–d.

Post-treatment Pain

VAS scores before treatment for all 746 patients in surgery, POP, radiation, and no local treatment groups were 5.70 ± 1.22, 5.53 ± 1.34, 6.62 ± 1.48, and 3.37 ± 1.38, respectively; scores were highest in the radiation group and lowest in the no local treatment group (p < 0.05). VAS scores in surgery, POP, and radiation groups decreased significantly to 4.78 ± 1.28, 4.37 ± 1.36, and 5.39 ± 1.31, respectively, at 12 weeks after local treatment (p < 0.05). VAS scores for patients in the no local treatment group did not significantly differ 12 weeks after enrollment. Detailed scores are shown in Fig. 3a.

Pre-treatment and post-treatment visual analog scale (VAS) scores and Quality of Life Questionnaire Bone Metastases Module (QLQ-BM22) subscores in all patients (a) and in training (b), test (c), and validation (d) sets. Unfilled circles indicate not significantly different from pre-treatment score (p > 0.05). Filled circles indicate significantly different from pre-treatment score (p < 0.05). LT local treatment, POP percutaneous osteoplasty

VAS scores in training, test, and validation sets all decreased significantly at 12 weeks after surgery, POP, or radiation (p < 0.05), with no significant differences among the three sets. Detailed scores are shown in Fig. 3b–d.

Post-treatment QoL

Pain sites (PS) and pain characteristic (PC) scores of the QLQ-BM22 before treatment for all 746 patients were highest in the radiation group and lowest in the no local treatment group (p < 0.05), while functional interference (FI) and psychosocial aspects (PA) scores were highest in the no local treatment group and lowest in the radiation group (p < 0.05). Patients had improved QoL scores 12 weeks after surgery, POP, or radiation (p < 0.05). PS and PC scores decreased significantly while FI and PA scores increased significantly at 12 weeks after local treatment in surgery, POP, and radiation groups (p < 0.05). PS, PC, FI, and PA scores for patients in the no local treatment group did not significantly differ 12 weeks after enrollment. Pre-treatment and post-treatment subscores in pain and functional domains in QLQ-BM22 are shown in Fig. 3a.

In training, test, and validation sets, PS and PC scores decreased significantly while FI and PA scores increased significantly at 12 weeks after surgery, POP, or radiation (p < 0.05), with no significant differences among the three sets. Detailed scores are shown in Fig. 3b–d.

Cost Valuation

Mean costs during 24 weeks for all 746 patients in surgery, POP, radiation, and no local treatment groups were $21,172 ± 8626, $16,142 ± 5078, $15,899 ± 5527, and $13,526 ± 5685, respectively; costs were highest in the surgery group and lowest in the no local treatment group (p < 0.05). There were no significant differences in mean costs among training, test, and validation sets in the four treatment groups. Detailed costs are shown in Fig. 4a and b.

Mean costs during 24 weeks in surgery, POP, radiation, and no local treatment groups (a). Mean costs during 24 weeks in all patients and in training, test, and validation sets (b). *Significantly higher cost compared to other three group (p < 0.05). #Significantly lower cost compared to other three group (p < 0.05). LT local treatment, POP percutaneous osteoplasty

Survival

Median follow-up was 15 months (range 6–41 months). The endpoint of analyses was overall survival time (OS), and a total of 548 patients died. The OS was 18.03 ± 0.45 months in all 746 patients, and the 1-year survival rate was 65.55%. OS was 15.50 ± 1.08, 16.72 ± 1.04, 16.90 ± 1.08, and 18.25 ± 0.54 months in surgery, POP, radiation, and no local treatment groups, respectively, with no significant differences. One-year survival rates were 61.11%, 60.68%, 63.38%, and 66.73% in surgery, POP, radiation, and no local treatment groups, respectively, with no significant differences. OS did not significantly differ among the three datasets.

Model Development and Validation

The DT model included VAS, bone metastases character, Frankel classification, Mirels scale, age, driver gene, and ALDH2 and ENO1 expression. Compared with the MDT, the DT model was superior to the other two machine learning models in predicting whether patients would receive local treatment, with an AUC of 0.89 for the DT model (95% CI 0.86–0.93), 0.77 for SVM model (95% CI 0.72–0.82), and 0.71 for BNN model (95% CI 0.66–0.76) (p > 0.05). The DT model had 89.44% sensitivity, 90.34% specificity, and 90.06% accuracy.

The DT model was also superior to the other two machine learning models in the test set, with an AUC of 0.85 for the DT model (95% CI 0.77–0.94), 0.78 for SVM model (95% CI 0.68–0.80), and 0.68 for BNN model (95% CI 0.57–0.80) (p > 0.05). The DT model had 83.87% sensitivity, 87.01% specificity, and 86.11% accuracy.

The DT model was used for further validation in clinical use. In the validation set, the MDT rejected the DT model decision to provide local treatment for nine patients and not provide local treatment for five patients. The AUC for DT was 0.88 (95% CI 0.81–0.96), with 86.11% sensitivity, 89.89% specificity, and 88.80% accuracy.

Discussion

Management of bone metastases has been considered palliative and not associated with patient prognosis and thus has not been given much importance in the past. Recently, however, it has become necessary to initiate bone management programs concurrently with cancer treatment to effectively reduce pain and improve patients’ QoL.

Similar to previous studies, surgery, POP, or radiation in this study provided significant pain relief and improved QoL [6, 8, 25,26,27,28]. We found that pain-related scores can be relieved quickly, but functional relief was slower than pain relief, especially in patients who underwent surgery and radiation. Surgical patients need to recover from postoperative trauma, and radiation has a slower effect on the recovery of mechanical stability. However, we found that the pain increased after 6 months after treatment, which was related to the characteristics of bone metastasis. Some patients underwent secondary local treatment. Breakthrough cancer pain (BTcP) is defined as “a transitory flare of pain that occurs on a background of relatively well-controlled baseline pain” [29]. It occurs in patients with cancer regardless of chronic pain management. Typical BTcP episodes are of moderate to severe intensity, rapid in onset (min), and of relatively short duration (median 30 min). In our study, local treatment was good at controlling chronic pain, but can not be rapid in onset of action.

In this study, we found that our MDT algorithm was effective in providing treatment decisions that provided significant pain relief and improved QoL. The mechanical stability, neurological risk, oncological parameters, and preferred treatment (MNOP) algorithm [30] suggests surgery or radiation as the main treatment for spinal metastases. Minimally invasive approaches such as POP are also recommended by our algorithm. We have treated hundreds of spinal PF and instabilities with POP instead of high-risk surgery. We find that patients recover spinal stability after POP with low morbidity, and our results here show that mean costs for spine metastases in the POP group were much lower than those in the surgery group. However, we note that POP does not easily restore structural integrity and weight-bearing for the appendicular skeleton and that surgery can quickly restore these functions with less risk. To prevent PF, we have used preventive surgery or POP, and our algorithm shows that surgery and POP are complementary. We prefer POP for spinal metastases and surgery for appendicular skeleton metastases.

Our results show that local treatment did not negatively influence OS for lung cancer patients with bone metastases. According to some studies, patients surgically treated for bone metastases survive for less than 10 months [26]. Recently, Tang et al. reported OS of 14 months in lung cancer patients with spinal metastases, and patients who underwent surgery had longer survival [27]. However, our study excluded patients with a life expectancy of less than 3 months, 92.6% patients received systemic medical treatments (57.9% for targeted agents), and Frankel classification in the no local treatment group was almost E, while in Tang’s study it was A–D, possibly accounting for the longer survival in our study.

Machine learning models can help guide treatment decisions. Although the MDT approach is an effective method to manage bone metastases, it can be difficult to manage patients who may develop serious SREs in a timely manner by holding weekly meetings. Alternatively our machine learning models based on routinely available clinical parameters were constructed for local treatment decision-making. XGBoost is a novel boosting tree-based ensemble algorithm that has gained wide popularity in the machine learning community [31]. The DT model showed greater accuracy than SVM and BNN models, and it included driver genes and that ALDH2 and ENO1 expression had higher accuracy, which is in line with current needs for precision medicine. For ethical reasons, the final decision was still left to the MDT. However, pain, QoL, mean cost, and OS of the four treatment groups did not significantly differ among training, test, and validation sets. Feasibility and stability of the DT model were satisfactory, and the DT model was good at determining whether patients should receive local treatment in prospective clinical validation. Thus, the DT model may help clinicians decide on local treatment for individual patients to reduce pain and improve patients’ QoL.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first attempt to use machine learning techniques for local treatment decision-making models in lung cancer patients with bone metastases. However, the algorithm cannot completely solve the problem of patient classification, and some treatments have not been carried out in our study, which represents a weakness. For example, stereotactic body radiation therapy for painful spine metastasis shows better results in local control and pain relief than standard 2D or 3D techniques [30], and recent development of immune checkpoint inhibitors has fundamentally changed how patients with metastatic lung cancer are treated [5]. However, machine learning models could only guide decisions about whether to apply local treatment or not, and only the accuracy of the DT model in local treatment decision-making compared with MDT was evaluated. However, as more patients receive local treatment, thus increasing data availability, we will be able to develop additional models that can better guide types of local treatment. Further, this study is limited in that it involved a single center and the number of patients in the test and validation sets is small. A randomized controlled multicenter trial to compare DT with MDT would be an effective validation in the future, although standardizing and homogenizing use of local treatment in different centers are challenging problems that remain to be solved.

Conclusion

Local treatment not only had no negative influence on OS but also provided significant pain relief and improved QoL in patients in our study. There were no significant differences in reducing pain and improving QoL among training, test, and validation sets. The DT model was best at determining whether patients should receive local treatment. Our machine learning model using clinical data can help guide clinicians to make local treatment decisions to reduce pain and improve patients’ QoL.

Change history

11 April 2021

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40122-021-00262-z

References

Coleman RE. Clinical features of metastatic bone disease and risk of skeletal morbidity. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12(20 Pt 2):6243s-s6249.

Coleman RE. Metastatic bone disease: clinical features, pathophysiology and treatment strategies. Cancer Treat Rev. 2001;27(3):165–76.

Cetin K, Christiansen CF, Jacobsen JB, Nørgaard M, Sørensen HT. Bone metastasis, skeletal-related events, and mortality in lung cancer patients: a Danish population-based cohort study. Lung Cancer. 2014;86(2):247–54.

Fairchild A. Palliative radiotherapy for bone metastases from lung cancer: evidence-based medicine? World J Clin Oncol. 2014;5(5):845–57.

Arbour KC, Riely GJ. Systemic therapy for locally advanced and metastatic non-small cell lung cancer: a review. JAMA. 2019;322(8):764–74.

Wedin R. Surgical treatment for pathologic fracture. Acta Orthop Scand Suppl. 2001;72(302):1–29.

Wang Z, Zhen Y, Wu C, et al. CT fluoroscopy-guided percutaneous osteoplasty for the treatment of osteolytic lung cancer bone metastases to the spine and pelvis. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2012;23(9):1135–42.

Pin Y, Paix A, Le Fèvre C, Antoni D, Blondet C, Noël G. A systematic review of palliative bone radiotherapy based on pain relief and retreatment rates. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2018;123:132–7.

Bongiovanni A, Recine F, Fausti V, et al. Ten-year experience of the multidisciplinary Osteoncology Center. Support Care Cancer. 2019;27(9):3395–402.

Hosseinzadeh F, Kayvanjoo AH, Ebrahimi M, Goliaei B. Prediction of lung tumor types based on protein attributes by machine learning algorithms. Springer Plus. 2013;2(1):238.

Duda RO, Hart PE, Stork DG. Pattern classification. 2nd ed. New York: Wiley; 2000.

Wang Z, Wen X, Lu Y, Yao Y, Zhao H. Exploiting machine learning for predicting skeletal-related events in cancer patients with bone metastases. Oncotarget. 2016;7(11):12612–22.

Fisher CG, DiPaola CP, Ryken TC, et al. A novel classification system for spinal instability in neoplastic disease: an evidence-based approach and expert consensus from the Spine Oncology Study Group. Spine. 2010;35(22):E1221-9.

Mirels H. Metastatic disease in long bones: a-proposed scoring system for diagnosing impending pathologic fractures. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1989;249:256–64.

Choi D, Crockard A, Bunger C, et al. Global Spine Tumor Study Group. Review of metastatic spine tumour classification and indications for surgery: the consensus statement of the Global Spine Tumour Study Group. Eur Spine J. 2010;19(2):215–22.

Rodolfo C, Campanacci DA. The treatment of metastases in the appendicular skeleton . J Bone Jt Surg Br. 2001;83(4):471–81.

Gasbarrini A, Boriani S, Capanna R, et al. Management of patients with metastasis to the vertebrae: recommendations from the Italian Orthopaedic Society (SIOT) Bone Metastasis Study Group. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2014;14(2):143–50.

Capanna R, Piccioli A, Di Martino A, et al. Management of long bone metastases: recommendations from the Italian Orthopaedic Society bone metastasis study group. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2014;14(10):1127–34.

Siegel GW, Biermann JS, Calinescu AA, Spratt DE, Szerlip NJ. Surgical approach to bone metastases. Curr Osteoporos Rep. 2018;16(4):512–8.

Yang M, Sun Y, Sun J, et al. Differentially expressed and survival-related proteins of lung adenoarcinoma with bone metastasis. Cancer Med. 2018;7(4):1081–92.

Joyce CR, Zutshi DW, Hrubes V, Mason RM. Comparison of fixed interval and visual analogue scales for rating chronic pain. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1975;8(6):415–20.

McDonald R, Ding K, Brundage M, et al. Effect of radiotherapy on painful bone metastases a secondary analysis of the NCIC clinical trials group symptom control trial SC.23. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3(7):953–9.

Osoba D, Rodrigues G, Myles J, Zee B, Pater J. Interpreting the significance of changes in health-related quality-of-life scores. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16(1):139–44.

Soloway MS, Hardeman SW, Hickey D, et al. Stratification of patients with metastatic prostate cancer based on extent of disease on initial bone scan. Cancer. 1988;61(1):195–202.

Anselmetti GC, Marcia S, Saba L, et al. Percutaneous vertebroplasty: multi-centric results from EVEREST experience in large cohort of patients. Eur J Radiol. 2012;81(12):4083–6.

Wood TJ, Racano A, Yeung H, Farrokhyar F, Ghert M, Deheshi BM. Surgical management of bone metastases: quality of evidence and systematic review. Ann Surg Oncol. 2014;21(13):4081–9.

Tang Y, Qu J, Wu J, et al. Effect of surgery on quality of life of patients with spinal metastasis from non-small-cell lung cancer. J Bone Jt Surg Am. 2016;98(5):396–402.

Nooh A, Goulding K, Isler MH, et al. Early improvement in pain and functional outcome but not quality of life after surgery for metastatic long bone disease. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2018;476(3):535–45.

Fallon M, Giusti R, Aielli F, et al. Management of cancer pain in adult patients: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines. Ann Oncol. 2018;29(Supplement 4):iv149–74.

Spratt DE, Beeler WH, de Moraes FY, et al. An integrated multidisciplinary algorithm for the management of spinal metastases: an International Spine Oncology Consortium report. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18(12):e720–30.

Chen T, Guestrin, C. Xgboost: a scalable tree boosting system. In: Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD international conference on knowledge discovery and data mining. KDD’16. 2016. pp. 785–794.

Acknowledgements

We thank the participants of the study. We appreciate the help of data analyst Ms. Yiru Shen from PerkinElmer for preliminary data during the study.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81602519, 81672852), Shanghai Municipal Health Commission (20164Y0099), Peak Plateau Project of Shanghai Jiao Tong University (20172024), and Shanghai Shen Kang 3-year plan of action project (16CR2007A). The journal’s Rapid Service Fee was funded by the authors.

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Authorship Contributions

Zhiyu Wang and Jing Sun: study concept, design, analysis, and manuscript drafting. Yi Sun, Yifeng Gu, Yongming Xu, Bizeng Zhao, and Yuehua Li: local treatment perform. Mengdi Yang, Guangyu Yao, and Yiyi Zhou: patient follow-up, data collection. Dongping Du and Hui Zhao: study concept, design, and manuscript editing. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Disclosures

Zhiyu Wang, Jing Sun, Yi Sun, Yifeng Gu, Yongming Xu, Bizeng Zhao, Mengdi Yang, Guangyu Yao, Yiyi Zhou, Yuehua Li, Dongping Du, and Hui Zhao declare they have nothing to disclose.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

The study was performed in accordance with ethical principles that have their origin in the Declaration of Helsinki and are consistent with International Conference on Harmonization (ICH)/Good Clinical Practice (GCP), applicable regulatory requirements, and the sponsor or its delegate’s policy on bioethics. This study was approved by the ethics committee of Shanghai Sixth People’s Hospital Affiliated to Shanghai Jiaotong University in October, 20, 2016 and the TRN is 2016-162. This study was registered in the Chinese Clinical Trial Registry (No. ChiCRT-ROC-16009501). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants in this study.

Data Availability

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Additional information

The original online version of this article was revised: to include the Equal contribution statement regarding authors Zhiyu Wang and Jing Sun.

Zhiyu Wang and Jing Sun have contributed equally and should be considered as co-first authors.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, Z., Sun, J., Sun, Y. et al. Machine Learning Algorithm Guiding Local Treatment Decisions to Reduce Pain for Lung Cancer Patients with Bone Metastases, a Prospective Cohort Study. Pain Ther 10, 619–633 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40122-021-00251-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40122-021-00251-2