Abstract

Purpose of Review

Literature from the past five years exploring roles of Three-Factor Eating Questionnaire (TFEQ) Restraint and Disinhibition in relation to adult obesity and eating disturbance (ED) was reviewed.

Recent Findings

Restraint has a mixed impact on weight regulation, diet quality, and vulnerability to ED, where it is related detrimentally to weight regulation, diet, and psychopathology, yet can serve as a protective factor. The impact of Disinhibition is potently related to increased obesity, poorer diet, hedonically driven food choices, and a higher susceptibility to ED.

Summary

Restraint and Disinhibition have distinct influences on obesity and ED and should be targeted differently in interventions. Further work is required to elucidate the mechanisms underlying TFEQ eating behavior traits.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

It is clear that the susceptibility of some individuals to gain weight and be vulnerable to problematic eating behaviors in an obesogenic environment is an important issue. The prevalence of obesity has doubled since 1980, with worldwide estimates of 108 million children and 604 million adults considered obese in 2015 [1]. Moreover, globally, there were 4.0 million deaths related to obesity, reflecting the detrimental impact of obesity on health [1]. Such susceptibility within the obesogenic environment implies the presence of particular dispositions to either create a positive energy balance or to create behaviors which try to control energy balance in those affected. These dispositions can be measured psychometrically; over the past 30 years, the Three-Factor Eating Questionnaire (TFEQ) [2] has gained great popularity in measuring eating behavior dispositions or traits, which are related to weight regulation. Other eating behavior trait scales do exist, for example, the Restraint Scale [3] and the Dutch Eating Behavior Questionnaire [4]; however, the major strength of the TFEQ is the existence of vast evidence to suggest an important and robust role for the TFEQ traits in obesity, eating styles, eating disturbance, and associated factors, such as personality (e.g., Bryant et al. [5] for a review of Disinhibition and see Mills et al. [6] for a review of Restraint). The popularity of the TFEQ is due to the utility of the eating behavior traits that it measures, hence why these traits are the focus of this particular review.

The TFEQ assesses three factors; Restraint, Disinhibition, and Hunger. Restraint refers to an individual’s concern over weight control and strategies which are adopted to maintain body weight and restrict eating, for instance, using small portions, avoiding fattening foods, and stopping eating before reaching satiation, in order to limit food intake. Disinhibition reflects a tendency towards overeating and eating opportunistically in an obesogenic environment, for example, eating in response to negative affect, being unable to resist food cues, and overeating in response to the palatability of food. Hunger is concerned with the extent to which hunger feelings are perceived and the extent to which such feelings then evoke food intake. For example, intense feelings of hunger resulting in consumption in excess of three meals per day, feeling an absence of satiety, or creating unpleasant gastric sensations [2]

Further psychometric evaluation has revealed several sub-factors within the TFEQ (see Table 1). For example, Bond et al. [7] identified three Disinhibition sub-factors; Habitual, Situational, and Emotional susceptibility; three Restraint sub-factors of Strategic Dieting Behavior, Attitude to Self-Regulation, and Avoidance of Fattening Food; and two Hunger sub-factors of Internal and External Locus. Westenhoefer et al. [8] discovered Rigid and Flexible Restraint, and Niemeier et al. [9] suggested Internal and External Disinhibition. In addition, shorter revised versions of the TFEQ have also been created for adults [10, 11] and children [12, 13]. The revised versions of the TFEQ assess three factors: Cognitive Restraint (CR), as in the original TFEQ; Uncontrolled Eating (UE)—an amalgamation of the Disinhibition and Hunger scales of the original TFEQ which refers to responsivity to food palatability, social cues and hunger, resulting in eating episodes; and Emotional Eating (EE), referring to eating episodes elicited by negative affect.

Previous work has demonstrated the important roles that these traits play in obesity and eating disturbance (e.g., see Bryant et al. [5] for a review); however, this evidential review is now dated. The aim of the current narrative review, therefore, is to explore the impact of the eating behavior traits, TFEQ Restraint and Disinhibition, upon obesity and eating disturbance, addressing literature from the last 5 years (2013–2018), in relation to adult body weight and obesity, disturbed and disordered eating, diet quality, cognitive profile, and weight loss.

Method

In this review, we considered literature from the last 5 years which assessed TFEQ Restraint and Disinhibition, or revised versions of the TFEQ (CR, UE and EE), in adults (18 years or older) and their roles in relation to issues of obesity and body weight, eating behavior, cognitive profile, diet quality, disturbed and disordered eating, and associated issues.

A literature search was performed in PsycINFO, Science Direct, and PubMed; this was restricted to English language. Epidemiological, observational, and intervention studies (including randomized control trials) were included and only original articles were reviewed. Reference lists and forward citations of included studies were screened. Titles and abstracts were screened independently for eligibility (EB). Full-text articles were independently screened for inclusion by EB, JR, LBP, and ERW using the following inclusion criteria:

- 1.

Use of an adult sample (18+ years).

- 2.

Use of normal weight or overweight/obese samples

- 3.

Studies which utilized the TFEQ to assess Restraint and Disinhibition.

- 4.

Studies published within the last 5 years (2013–2018).

From the search, 76 papers were retained as eligible and reviewed. Papers were excluded if Restraint and/or Disinhibition were assessed using any other tool than the TFEQ, if adolescent or child samples were included, if the TFEQ was used in a study, but no results pertaining to Disinhibition or Restraint were reported, or if the paper was a review article. The papers were organized into sections depending upon the subject matter of the research, to look at the impact of eating behavior traits on body weight and obesity and on diet quality and cognitive profile, in relation to disturbed and disordered eating patterns and considering the impact of eating behavior traits on weight loss interventions.

Eating Behavior Traits, Body Weight, and Obesity

Evidence suggests that as body mass index increases, Disinhibition and Hunger increase while Restraint decreases [14,15,16,17]. When considering Disinhibition (and UE and EE), there is a consistent representation that a higher level of Disinhibition is positively associated with BMI [18,19,20,21] as well as weight and fat mass [22, 23], while a higher UE [24], UE and EE [25, 26], and EE [26,27,28,29] are associated with an increased BMI. These data are supported by genetic studies which reveal that genes associated with increased BMI are also positively associated with UE and EE [27], suggesting eating behavior traits may be partially genetically determined [30,31,32]. In addition, parent-offspring eating behavior dyads indicate that parental Rigid Restraint and Disinhibition are related to a higher offspring BMI [33], suggesting that family environmental factors are also related to obesity transmission within families.

The evidence for Restraint is conflicting and proposes that Restraint is positively related to BMI [19, 27, 29, 34] where a higher level of Restraint increases the risk of obesity as much as fourfold [24] or where Restraint is lower in obese women [35], or not related to BMI at all [22, 25]. The mechanisms underlying why variations in the BMI and body composition of those with differing Disinhibition and Restraint scores exist are complex, and can at least be partially explained by diet quality and the eating patterns adopted by these individuals, for example, whether a flexible or rigid approach to Restraint is adopted, or depending upon the interaction between Disinhibition and Restraint and the subsequent impact of this on body weight.

Eating Behavior Traits, Diet Quality, and Cognitive Profile

As expected, Disinhibition was found to be detrimentally associated with diet quality [14, 36] and self-determination in relation to eating behavior [37]. In addition, the amalgamated Disinhibition and Hunger factors of UE and EE are also positively associated with energy and fat intake [27], possessing a diagnosis of diabetes and responding to food insecurity in older adults [38]. Together, these suggest a behavioral profile which is detrimental to weight regulation and maintaining good health. Surprisingly, however, Disinhibition was not significantly related to eating in the absence of hunger in lean individuals [39], or was it related to snacking initiation [40]. The poorer dietary behavior of those with a higher Disinhibition (or UE) could be explained in part, by the higher impulsivity in relation to palatable foods possessed, regardless of their Restraint score [41], suggesting a more automatic response to food. Here, a cognitive profile emerges which supports a less healthful and more hedonically driven dietary response. For instance, those with a high Disinhibition show a higher liking [42], and wanting [18] of food, stronger food cravings [23, 43, 44], and a lower willingness to control eating behavior. In addition, they demonstrate a higher positive reinforcing value of food [45], show a vulnerability to accepting distressing thoughts (from negative reinforcement) [46], and have lower eating-related mindfulness (for those with a higher UE and EE) [47]. Indeed, collectively, this evidence supports the theoretical underpinning of Disinhibition, UE and EE, whereby those with higher scores are more motivated by the palatability of food, eat opportunistically, and are susceptible to eating in response to emotion as opposed to eating intuitively [2, 10, 11].

Responsiveness to emotion has also been found to impact diet quality and eating patterns in these individuals. Those with a higher UE and EE have a higher susceptibility to perceived stress [48] and a lower distress tolerance [49], and EE was associated with burnout in students [50]. Such responsiveness to negative emotions was also associated with lower eating competence, higher responsiveness to emotional and external cues to elicit eating episodes, and a poorer diet quality [48]. In addition to this, a higher level of Disinhibition was related to a negative self-evaluation and poorer eating regulation [51]. Unexpectedly, however, functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) evidence suggests that Restraint, Disinhibition, and Hunger are not associated with brain regions connected with food cue reactivity [52]. These studies demonstrate how an eating behavior profile characterized by self-medicating negative affect can lead to poorer control over eating behavior and therefore a poorer weight regulation.

On the other hand, similar to the BMI evidence, the findings in relation to Restraint are mixed. It is possible that these mixed findings could reflect the type of Restraint exerting the most influence (e.g., Rigid or Flexible Restraint) on an individual; however, studies do not consistently report these Restraint sub-factors consistently to state this conclusively. Restraint was found to be related to a more healthful dietary profile [14, 36], a higher, but non-significant, satiety quotient [53], a lower energy intake [18], lower craving and liking of processed foods [54], a lower fat intake [27], and lower appetite ratings [55], all of which supports a behavioral profile conducive for weight regulation. This is in line with the behavioral tendencies measured by TFEQ Restraint. Restraint measures an individual’s cognitive effort to control their food intake to manage their body weight [2, 10]. Unlike other measures of Restraint, TFEQ Restraint only assesses efforts to regulate food intake and body weight, whereas other measures of Restraint, such as the Restraint Scale [3], also assess periodic disruption of this imposed restraint over food consumption, which leads to overeating episodes. Thus, it makes theoretical sense that those with a higher TFEQ Restraint engage in behaviors which favor a tighter regulation over energy intake and subsequently body weight, with a lower tendency to overeat. However, counter-intuitively, Restraint is also related to larger portion norms for men [56], predicts food intake from a test meal [57], and is not associated with compensatory behaviors to control for energy intake [58]. Furthermore, no effect of Restraint on consumption was found when portion size was altered [59] or in adherence to a dietary intervention [60].

This presents a complex picture of the impact of Restraint on dietary composition. A possible explanation for these differences could be derived from the goal conflict theory [61] which suggests weight regulation issues result from the conflict between the goal of weight control and the goal of eating enjoyment; the goal of weight control is often subjugated by the hedonic expectation of food [62]. The current obesogenic environment presents a plethora of palatable foods and so the goal of eating enjoyment is more often primed, meaning that a higher cognitive effort is required to maintain the goal of weight control [61]. This cognitive effort is likely to be particularly challenging when other external factors are present (for example, relationships, work-life balance, emotional fatigue) which may reduce the individual’s cognitive capacity to review and control their food intake, potentially leading to the goal of eating enjoyment being more easily prioritized [61]. Consequently, this then results in unhealthy eating patterns and weight gain [63]. Indeed, supporting evidence suggests that attempts at Restraint can create food cravings, which increases the risk of further weight gain and obesity [64]. Here, higher Restraint led to a higher food craving, which was subsequently related to a higher UE and EE [64].

Eating Behavior Traits and Disordered and Disturbed Eating

Both Disinhibition and Restraint are found to be related to the psychopathology of disturbed eating behavior and eating disorders. Disinhibition appears to be a behavioral indicator of a loss of control over eating, where an individual consumes greater quantities of food, independently of their level of Restraint [65]. This is reflected in those who have a binge eating disorder (BED) diagnosis possessing a higher Disinhibition and Hunger [66]. Increases in objective and subjective binge eating and objective overeating are also observed with higher levels of Disinhibition [67], whereas Restraint has been associated with objective binge eating but not overeating [67].

Furthermore, Disinhibition can predict excessive consumption and objective binge eating episodes before and after fasting periods, where eating disorder risk has been associated with fasting behaviors (complete fasting for 24 hours) [68]. Disinhibition and self-reported, voluntary fasting frequency predicted positive shifts in post-fast body image [69] suggesting that self-imposed food restriction can have a positive reinforcement impact on non-clinical samples. Overall, however, these studies suggest that Disinhibition is related not only to eating disorder susceptibility but also to more pathological symptomatology within disordered eating.

This is corroborated with evidence from those who score highly on the Yale Food Addiction Scale, reporting higher levels of Disinhibition, a high tendency to overeat [70, 71], and a lower distress tolerance [49], which exacerbates their overeating response. In concordance, evidence also suggests that disordered and disturbed eating behaviors are similarly related to higher depression and Disinhibition levels [23]. Indeed, CR, UE, and EE have been related to higher neuroticism, anxiety, and depression scores, which were also associated with dysfunctional eating patterns [72], weight stigma, and weight bias internalization [73]. Significant feelings of guilt and food craving have also been reported by those with a high Disinhibition [44] and high EE [35], where the craving was subsequently related to binge eating and obesity. Furthermore, Disinhibition has been found to be negatively associated with intuitive eating and body appreciation [74]. Thus, a pattern of behaviors associated with disturbed eating patterns and poorer mental health for those with a high Disinhibition emerges, which is compounded by a lower tolerance to adverse emotional states.

On the other hand, Restraint is used as a means to control leanness to strive towards body image ideals [75]; here, neuroticism partially mediates the associations between Restraint, body dissatisfaction, and binge eating [76]. The association of Restraint with higher eating disordered attitudes is not always expressed in energy restriction; evidence suggests that in female students, Restraint resulted in sub-optimal energy consumption relative to physiological need as a result of higher physical activity rather than energy restriction [28]. In support of this, Linardon and Mitchel [74] found that both Flexible and Rigid Restraint predicted exercising for weight loss and body checking, while Rigid Restraint predicted over-evaluation of weight and shape. In this study, Restraint was found to be a strong predictor of both disordered eating and negative body image [74]. Surprisingly, no relationship between mindful eating and Restraint has been found [34]. However, a negative relationship between Restraint and intuitive eating existed, which predicted higher disordered eating levels [34] Restraint as negatively associated with intuitive eating is not unexpected, since Restraint relies on cognitive effort to restrict food intake, rather than relying on internal satiety signals to control energy intake. This is in line with evidence which suggest a reliance on increased physical activity to control body weight in Restrained individuals, supporting more external, than internal, control imposed on energy restriction [28].

Eating Behavior Traits and Weight Loss Interventions

The eating behavior trait profiles of individuals undergoing weight loss intervention are clearly of high importance, as the eating behavior response of an individual can determine their weight loss success. There are robust findings that in following weight loss interventions, a change in eating behavior traits are seen, whereby there is an increase in Restraint [77, 78] [52, 79, 80] and a decrease in Disinhibition (or UE) [81, 82] [52, 79, 80] and Hunger [83,84,85,86,87]. However, one study found no change in TFEQ factors despite significant weight loss [60]. This could be a result of the dietary intervention imposed which required participants to adhere to various vegetarian and vegan diets. In comparison, those studies which utilized, for example, the Mediterranean diet [83] and high-protein and high0carbohydrate diets [79], calorie restricting diets [88], and lifestyle intervention including dietary advice [80] saw increases in TFEQ Restraint and decreases in Disinhibition. Weight loss with these diets was associated with increases in Restraint [80, 88], decreases in Disinhibition [79], or both [83]. It is plausible that changes in eating behavior traits are associated with changes in appetite peptides, where TFEQ Hunger positively predicted ghrelin levels during weight loss [85]. Even though Disinhibition and Restraint did not reach significance in this study, further work needs to be done to explore the relationship between TFEQ, weight loss, and weight loss maintenance. Whether the weight loss itself leads to changes in eating behavior traits, or whether changes in eating behavior traits cause weight loss, or an interaction between the two requires further elucidation.

However, evidence does suggest that weight loss success is related to changes in eating behavior traits, whereby an increase in Flexible Restraint and decrease in Rigid Restraint is related to greater weight loss [89], and where a reduction in Disinhibition predicts weight loss over a 12-month period [79]. In addition, decreases in Restraint and increases in Disinhibition are found to be associated with weight regain over 10 years [90]. The TFEQ eating behavior traits do not act in isolation, for example, even though Restraint was the best predictor of weight reduction, the effect of Restraint on changes in weight and anthropometry was found to be moderated by increases in Disinhibition [91]. Further work examining the interaction between the eating behavior traits on weight loss success is warranted.

Bariatric surgery candidates are found to have higher Disinhibition and Hunger scores [92], although this is not always the case when comparing surgical with non-surgical candidates [93]. Following surgery, a robust finding is that Disinhibition (or UE and EE) decreases, alongside either an increase in Restraint [84, 94,95,96] or no change in Restraint [97,98,99,100], thus indicating a change in eating behavior traits which favors weight regulation. Baseline scores usually show limited ability in predicting post-surgery weight loss success. However, evidence suggests that baseline Restraint negatively impacts post-surgical weight loss, while baseline Disinhibition is positively correlated with weight reduction [93, 101]. This suggests that bariatric surgery is effective in improving the problematic eating patterns displayed by those with a high Disinhibition, which results in a greater weight loss. There is evidence that changes in eating behaviors post-surgery are more strongly associated with weight loss success. Those who lose more weight notice a greater reduction in Disinhibition and Hunger between 1 and 10 years post-surgery [94] or see an increase in Restraint and a decrease in UE and EE [102]. Weight loss success is therefore related to those who show an eating behavior profile which favors body weight regulation [95]. Therefore, eating behavior traits make a potent contribution to weight loss success following bariatric surgery. Despite this, a study by Parker et al. [103] evaluated various measures of disordered eating (including the TFEQ) in bariatric surgery patients; they concluded that none of the original measures evaluated were suitable for this cohort in their original forms. The authors concluded that the Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire was the most suitable measure for use in pre- and post-operative scenarios.

Conclusion

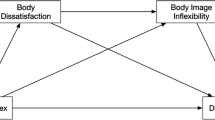

This narrative review has demonstrated that both Disinhibition and Restraint play an important role in obesity status, diet quality, and on the psychopathology of disturbed and disordered eating behaviors (Fig. 1). Due to the observational nature of many of the studies included here, a causal relationship between these eating behavior traits, obesity, and eating disturbance cannot be inferred. However, understanding what characterizes individuals with high scores on these eating behavior traits is important, as such insight could serve to improve interventions for weight loss and for improving eating disorder symptomatology. For instance, those with a high Disinhibition are more vulnerable to having an increased BMI and fat mass, poor diet quality, poorer health, more problematic eating behaviors, weight regain following weight loss, and more binge eating, food craving, and food addiction. Conversely, the impact of Restraint is mixed. On one hand, Restraint is related to a lower body weight, better weight regulation, and a better diet quality. On the other hand, Restraint is additionally related to a susceptibility to obesity, a poorer diet, and overeating. Where the impact of Disinhibition on obesity is potent in increasing energy intake and susceptibility to disturbed eating, the action of cognitive Restriction produces differential results, perhaps due to difficulty in maintaining cognitive control in an obesogenic environment replete with palatable foods. This complexity suggests that intervention should target reducing Disinhibition, rather than increasing Restraint.

Furthermore, the association of TFEQ Restraint and Disinhibition with the psychopathology of disturbed and disordered eating is also of great importance. High levels of Disinhibition are robustly related to a higher susceptibility to disordered eating and more pathological symptomatology of eating disorders. High Disinhibition individuals also have higher levels of adverse behaviors and thought patterns associated with disturbed eating, such as internalization of weight bias and stigma, lower body appreciation and guilt, and further increasing susceptibility to eating disorders, particularly when coupled with a lower tolerance of distress. TFEQ Restraint is also related to increased levels of disturbed and disordered eating behaviors and associated negative behaviors. Studies, which assess eating disorders, more often use the Eating Disorder Inventory measure of Restraint, rather than the TFEQ Restraint, explaining the relatively few studies included here which examine disordered eating. However, the evidence presented suggests that the TFEQ Restraint is effective in identifying problematic and disturbed eating behavior in clinical samples. Specific targeting of the reduction of Disinhibition and regulation of Restraint (improving Flexible Restraint and decreasing Rigid Restraint) within interventions to counteract disturbed and disordered eating is warranted[104].

In addition, it is important to note that scores on the TFEQ factors tend to be higher in females than males [15, 17, 19, 64, 105] suggesting differences in eating behavior traits between men and women. However, Leblanc et al. [37] found few differences between the sexes on the TFEQ, with women only scoring significantly higher in Emotional Susceptibility to Disinhibition. Furthermore, older individuals are found to have higher Restraint [59, 105] and lower Disinhibition [17, 27, 105]. It is unclear why these differences exist between men and women, and over age categories, and further exploration is necessary. However, these differences are of consequence, particularly when designing interventions to combat obesity or disturbed and disordered eating behaviors, as these approaches may need to be more specifically tailored. In addition, much of the research uses samples comprised mainly of women; leaving paucity in TFEQ research regarding men, and perhaps providing a skewed picture of the impact of TFEQ eating behavior traits on obesity and disturbed and disordered eating.

References

Afshin A, Forouzanfar MH, Reitsma MB, Sur P, Estep K, Lee A, et al. Health effects of overweight and obesity in 195 countries over 25 years. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(1):13–27. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1614362.

Stunkard AJ, Messick S. The three-factor eating questionnaire to measure dietary restraint, disinhibition and hunger. J Psychosom Res. 1985;29(1):71–83.

Herman CP, Mack D. Restrained and unrestrained eating. J Pers. 1975;43(4):647–60.

van Strien T, Frijters JER, Bergers GPA, Defares PB. The Dutch Eating Behavior Questionnaire (DEBQ) for assessment of restrained, emotional, and external eating behavior. Int J Eat Disord. 1986;5(2):295–315. https://doi.org/10.1002/1098-108x(198602)5:2<295::aid-eat2260050209>3.0.co;2-t.

Bryant EJ, King NA, Blundell JE. Disinhibition: its effects on appetite and weight regulation. Obes Rev. 2008;9(5):409–19. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-789X.2007.00426.x.

Mills JS, Weinheimer L, Polivy J, Herman CP. Are there different types of dieters? A review of personality and dietary restraint. Appetite. 2018;125:380–400. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2018.02.014.

Bond MJ, McDowell AJ, Wilkinson JY. The measurement of dietary restraint, disinhibition and hunger: an examination of the factor structure of the Three Factor Eating Questionnaire (TFEQ). Int J of Obesity. 2001;25(6):900–6. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ijo.0801611.

Westenhoefer J, Stunkard AJ, Pudel V. Validation of the flexible and rigid control dimensions of dietary restraint. The International journal of eating disorders. 1999;26(1):53–64.

Niemeier HM, Phelan S, Fava JL, Wing RR. Internal disinhibition predicts weight regain following weight loss and weight loss maintenance. Obesity (Silver Spring, Md). 2007;15(10):2485–94. https://doi.org/10.1038/oby.2007.295.

Cappelleri JC, Bushmakin AG, Gerber RA, Leidy NK, Sexton CC, Lowe MR, et al. Psychometric analysis of the Three-Factor Eating Questionnaire-R21: results from a large diverse sample of obese and non-obese participants. Int J of Obesity. (2005). 2009;33(6):611–20. https://doi.org/10.1038/ijo.2009.74.

Karlsson J, Persson LO, Sjostrom L, Sullivan M. Psychometric properties and factor structure of the Three-Factor Eating Questionnaire (TFEQ) in obese men and women. Results from the Swedish Obese Subjects (SOS) study. Int J of Obesity. 2000;24(12):1715–25.

Martín-García M, Vila-Maldonado S, Rodríguez-Gómez I, Faya FM, Plaza-Carmona M, Pastor-Vicedo JC, et al. The Spanish version of the Three Factor Eating Questionnaire-R21 for children and adolescents (TFEQ-R21C): Ppychometric analysis and relationships with body composition and fitness variables. Physiol Behav. 2016;165:350–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physbeh.2016.08.015.

Bryant EJ, Thivel D, Chaput J-P, Drapeau V, Blundell JE, King NA. Development and validation of the Child Three-Factor Eating Questionnaire (CTFEQr17). Public Health Nutr. 2018;21(14):2558–67. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980018001210.

Bernstein EE, Nierenberg AA, Deckersbach T, Sylvia LG. Eating behavior and obesity in bipolar disorder. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2015;49(6):566–72. https://doi.org/10.1177/0004867414565479.

Ernst B, Wilms B, Thurnheer M, Schultes B. Eating behaviour in treatment-seeking obese subjects - influence of sex and BMI classes. Appetite. 2015;95:96–100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2015.06.019.

Thomas EA, Bechtell JL, Vestal BE, Johnson SL, Bessesen DH, Tregellas JR, et al. Eating-related behaviors and appetite during energy imbalance in obese-prone and obese-resistant individuals. Appetite. 2013;65:96–102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2013.01.015.

Davison KM. The relationships among psychiatric medications, eating behaviors, and weight. Eat Behav. 2013;14(2):187–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eatbeh.2013.01.001.

French SA, Mitchell NR, Finlayson G, Blundell JE, Jeffery RW. Questionnaire and laboratory measures of eating behavior. Associations with energy intake and BMI in a community sample of working adults. Appetite. 2014;72:50–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2013.09.020.

Blumfield ML, Bei B, Zimberg IZ, Cain SW. Dietary disinhibition mediates the relationship between poor sleep quality and body weight. Appetite. 2018;120:602–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2017.10.022.

Batra P, Das SK, Salinardi T, Robinson L, Saltzman E, Scott T, et al. Eating behaviors as predictors of weight loss in a 6 month weight loss intervention. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2013;21(11):2256–63. https://doi.org/10.1002/oby.20404.

Epstein LH, Lin H, Carr KA, Fletcher KD. Food reinforcement and obesity. Appetite. 2012;58(1):157–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2011.09.025.

Hootman KC, Guertin KA, Cassano PA. Stress and psychological constructs related to eating behavior are associated with anthropometry and body composition in young adults. Appetite. 2018;125:287–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2018.01.003.

Keeler CL, Mattes RD, Tan SY. Anticipatory and reactive responses to chocolate restriction in frequent chocolate consumers. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2015;23(6):1130–5. https://doi.org/10.1002/oby.21098.

Porter Starr K, Fischer JG, Johnson MA. Eating behaviors, mental health, and food intake are associated with obesity in older congregate meal participants. J Nutr Gerontol Geriatr. 2014;33(4):340–56. https://doi.org/10.1080/21551197.2014.965375.

Iceta S, Julien B, Seyssel K, Lambert-Porcheron S, Segrestin B, Blond E, et al. Ghrelin concentration as an indicator of eating-disorder risk in obese women. Diabetes Metab. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.diabet.2018.01.006.

O'Brien KS, Latner JD, Puhl RM, Vartanian LR, Giles C, Griva K, et al. The relationship between weight stigma and eating behavior is explained by weight bias internalization and psychological distress. Appetite. 2016;102:70–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2016.02.032.

Cornelis MC, Rimm EB, Curhan GC, Kraft P, Hunter DJ, Hu FB, et al. Obesity susceptibility loci and uncontrolled eating, emotional eating and cognitive restraint behaviors in men and women. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2014;22(5):E135–41. https://doi.org/10.1002/oby.20592.

Rocks T, Pelly F, Slater G, Martin LA. The relationship between dietary intake and energy availability, eating attitudes and cognitive restraint in students enrolled in undergraduate nutrition degrees. Appetite. 2016;107:406–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2016.08.105.

Lopez-Cepero A, Frisard CF, Lemon SC, Rosal MC. Association of dysfunctional eating patterns and metabolic risk factors for cardiovascular disease among Latinos. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2018;118(5):849–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jand.2017.06.007.

Jacob R, Drapeau V, Tremblay A, Provencher V, Bouchard C, Perusse L. The role of eating behavior traits in mediating genetic susceptibility to obesity. Am J Clin Nutr. 2018;108(3):445–52. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/nqy130.

de Lauzon-Guillain B, Clifton EA, Day FR, Clement K, Brage S, Forouhi NG, et al. Mediation and modification of genetic susceptibility to obesity by eating behaviors. Am J Clin Nutr. 2017;106(4):996–1004. https://doi.org/10.3945/ajcn.117.157396.

Konttinen H, Llewellyn C, Wardle J, Silventoinen K, Joensuu A, Mannisto S, et al. Appetitive traits as behavioural pathways in genetic susceptibility to obesity: a population-based cross-sectional study. Sci Rep. 2015;5:14726. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep14726.

Gallant AR, Tremblay A, Perusse L, Despres JP, Bouchard C, Drapeau V. Parental eating behavior traits are related to offspring BMI in the Quebec Family Study. Int J Obes. 2013;37(11):1422–6. https://doi.org/10.1038/ijo.2013.14.

Anderson LM, Reilly EE, Schaumberg K, Dmochowski S, Anderson DA. Contributions of mindful eating, intuitive eating, and restraint to BMI, disordered eating, and meal consumption in college students. Eat Weight Disord. 2016;21(1):83–90. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-015-0210-3.

Jeanes YM, Reeves S, Gibson EL, Piggott C, May VA, Hart KH. Binge eating behaviours and food cravings in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Appetite. 2017;109:24–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2016.11.010.

Aguirre TM, Kuster JT, Koehler AE. Relationship between eating behavior and dietary intake in rural Mexican-American mothers. J Immigr Minor Health. 2017;19(1):225–7. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-015-0324-8.

Leblanc V, Begin C, Corneau L, Dodin S, Lemieux S. Gender differences in dietary intakes: what is the contribution of motivational variables? J Hum Nutr Diet. 2015;28(1):37–46. https://doi.org/10.1111/jhn.12213.

Myles T, Porter Starr KN, Johnson KB, Sun Lee J, Fischer JG, Ann JM. Food insecurity and eating behavior relationships among congregate meal participants in Georgia. J Nutr Gerontol Geriatr. 2016;35(1):32–42. https://doi.org/10.1080/21551197.2015.1125324.

Feig EH, Piers AD, Kral TVE, Lowe MR. Eating in the absence of hunger is related to loss-of-control eating, hedonic hunger, and short-term weight gain in normal-weight women. Appetite. 2018;123:317–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2018.01.013.

Fay SH, White MJ, Finlayson G, King NA. Psychological predictors of opportunistic snacking in the absence of hunger. Eat Behav. 2015;18:156–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eatbeh.2015.05.014.

Leitch MA, Morgan MJ, Yeomans MR. Different subtypes of impulsivity differentiate uncontrolled eating and dietary restraint. Appetite. 2013;69:54–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2013.05.007.

Yeomans MR, Prescott J. Smelling the goodness: sniffing as a behavioral measure of learned odor hedonics. J Exp Psychol Anim Learn Cogn. 2016;42(4):391–400. https://doi.org/10.1037/xan0000120.

Meule A, Müller A, Gearhardt AN, Blechert J. German version of the Yale Food Addiction Scale 2.0: prevalence and correlates of ‘food addiction’ in students and obese individuals. Appetite. 2017;115:54–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2016.10.003.

Van Gucht D, Soetens B, Raes F, Griffith JW. The Attitudes to Chocolate Questionnaire. Psychometric properties and relationship with consumption, dieting, disinhibition and thought suppression. Appetite. 2014;76:137–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2014.01.078.

Carr KA, Lin H, Fletcher KD, Epstein LH. Food reinforcement, dietary disinhibition and weight gain in nonobese adults. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2014;22(1):254–9. https://doi.org/10.1002/oby.20392.

Schaumberg K, Anderson DA, Anderson LM, Reilly EE, Gorrell S. Dietary restraint: what’s the harm? A review of the relationship between dietary restraint, weight trajectory and the development of eating pathology. Clin Obes. 2016;6(2):89–100. https://doi.org/10.1111/cob.12134.

Fisher NR, Mead BR, Lattimore P, Malinowski P. Dispositional mindfulness and reward motivated eating: the role of emotion regulation and mental habit. Appetite. 2017;118:41–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2017.07.019.

Järvelä-Reijonen E, Karhunen L, Sairanen E, Rantala S, Laitinen J, Puttonen S, et al. High perceived stress is associated with unfavorable eating behavior in overweight and obese Finns of working age. Appetite. 2016;103:249–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2016.04.023.

Kozak AT, Davis J, Brown R, Grabowski M. Are overeating and food addiction related to distress tolerance? An examination of residents with obesity from a U.S. metropolitan area. Obes Res Clin Pract. 2017;11(3):287–98. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.orcp.2016.09.010.

Kristanto T, Chen WS, Thoo YY. Academic burnout and eating disorder among students in Monash University Malaysia. Eat Behav. 2016;22:96–100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eatbeh.2016.03.029.

Duarte C, Matos M, Stubbs RJ, Gale C, Morris L, Gouveia JP, et al. The impact of shame, self-criticism and social rank on eating behaviours in overweight and obese women participating in a weight management programme. PLoS One. 2017;12(1):e0167571. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0167571.

Kahathuduwa CN, Davis T, O'Boyle M, Binks M. Do scores on the Food Craving Inventory and Three-Factor Eating Questionnaire correlate with expected brain regions of interest in people with obesity? Physiol Behav. 2018;188:1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physbeh.2018.01.018.

Drapeau V, Blundell J, Gallant AR, Arguin H, Després JP, Lamarche B, et al. Behavioural and metabolic characterisation of the low satiety phenotype. Appetite. 2013;70:67–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2013.05.022.

Polk SE, Schulte EM, Furman CR, Gearhardt AN. Wanting and liking: separable components in problematic eating behavior? Appetite. 2017;115:45–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2016.11.015.

Smithson EF, Hill AJ. It is not how much you crave but what you do with it that counts: behavioural responses to food craving during weight management. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2017;71(5):625–30. https://doi.org/10.1038/ejcn.2016.235.

Lewis HB, Forwood SE, Ahern AL, Verlaers K, Robinson E, Higgs S, et al. Personal and social norms for food portion sizes in lean and obese adults. Int J Obes. 2015;39(8):1319–24. https://doi.org/10.1038/ijo.2015.47.

Guillocheau E, Davidenko O, Marsset-Baglieri A, Darcel N, Gaudichon C, Tomé D, et al. Expected satiation alone does not predict actual intake of desserts. Appetite. 2018;123:183–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2017.12.022.

Jones MD, Crowther JH. Predicting the onset of inappropriate compensatory behaviors in undergraduate college women. Eat Behav. 2013;14(1):17–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eatbeh.2012.10.009.

Haire C, Raynor HA. Weight status moderates the relationship between package size and food intake. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2014;114(8):1251–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jand.2013.12.022.

Moore WJ, McGrievy ME, Turner-McGrievy GM. Dietary adherence and acceptability of five different diets, including vegan and vegetarian diets, for weight loss: The New DIETs study. Eat Behav. 2015;19:33–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eatbeh.2015.06.011.

Stroebe W, van Koningsbruggen GM, Papies EK, Aarts H. Why most dieters fail but some succeed: a goal conflict model of eating behavior. Psychol Rev. 2013;120(1):110–38. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0030849.

Veling H, Aarts H, Stroebe W. Fear signals inhibit impulsive behavior toward rewarding food objects. Appetite. 2011;56(3):643–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2011.02.018.

van Strien T, Herman CP, Verheijden MW. Dietary restraint and body mass change. A 3-year follow up study in a representative Dutch sample. Appetite. 2014;76:44–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2014.01.015.

Verzijl CL, Ahlich E, Schlauch RC, Rancourt D. The role of craving in emotional and uncontrolled eating. Appetite. 2018;123:146–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2017.12.014.

Forney KJ, Bodell LP, Haedt-Matt AA, Keel PK. Incremental validity of the episode size criterion in binge-eating definitions: an examination in women with purging syndromes. Int J Eat Dis. 2016;49(7):651–62. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.22508.

Vinai P, Da Ros A, Speciale M, Gentile N, Tagliabue A, Vinai P, et al. Psychopathological characteristics of patients seeking for bariatric surgery, either affected or not by binge eating disorder following the criteria of the DSM IV TR and of the DSM 5. Eat Behav. 2015;16:1–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eatbeh.2014.10.004.

Mailloux G, Bergeron S, Meilleur D, D'Antono B, Dube I. Examining the associations between overeating, disinhibition, and hunger in a nonclinical sample of college women. Int J Behav Med. 2014;21(2):375–84. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12529-013-9306-1.

Schaumberg K, Anderson DA, Reilly EE, Anderson LM. Does short-term fasting promote pathological eating patterns? Eat Behav. 2015;19:168–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eatbeh.2015.09.005.

Schaumberg K, Anderson DA. Does short-term fasting promote changes in state body image? Body Image. 2014;11(2):167–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2014.01.005.

Ruddock HK, Field M, Hardman CA. Exploring food reward and calorie intake in self-perceived food addicts. Appetite. 2017;115:36–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2016.12.003.

Ruddock HK, Hardman CA. Guilty pleasures: the effect of perceived overeating on food addiction attributions and snack choice. Appetite. 2018;121:9–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2017.10.032.

Gade H, Hjelmesaeth J, Rosenvinge JH, Friborg O. Effectiveness of a cognitive behavioral therapy for dysfunctional eating among patients admitted for bariatric surgery: a randomized controlled trial. J Obes. 2014;2014:127936. https://doi.org/10.1155/2014/127936.

O'Brien A, Watson HJ, Hoiles KJ, Egan SJ, Anderson RA, Hamilton MJ, et al. Eating disorder examination: factor structure and norms in a clinical female pediatric eating disorder sample. Int J Eat Dis. 2016;49(1):107–10. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.22478.

Linardon J, Mitchell S. Rigid dietary control, flexible dietary control, and intuitive eating: evidence for their differential relationship to disordered eating and body image concerns. Eat Behav. 2017;26:16–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eatbeh.2017.01.008.

Ozimok B, Lamarche L, Gammage KL. The relative contributions of body image evaluation and investment in the prediction of dietary restraint in men. J Health Psychol. 2015;20(5):592–601. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105315573434.

Luo J, Forbush KT, Williamson JA, Markon KE, Pollack LO. How specific are the relationships between eating disorder behaviors and perfectionism? Eat Behav. 2013;14(3):291–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eatbeh.2013.04.003.

Steinberg DM, Tate DF, Bennett GG, Ennett S, Samuel-Hodge C, Ward DS. Daily self-weighing and adverse psychological outcomes: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Prev Med. 2014;46(1):24–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2013.08.006.

Rocha J, Paxman J, Dalton C, Winter E, Broom DR. Effects of a 12-week aerobic exercise intervention on eating behaviour, food cravings, and 7-day energy intake and energy expenditure in inactive men. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2016;41(11):1129–36. https://doi.org/10.1139/apnm-2016-0189.

Cheng HL, Griffin H, Claes BE, Petocz P, Steinbeck K, Rooney K, et al. Influence of dietary macronutrient composition on eating behaviour and self-perception in young women undergoing weight management. Eat Weight Disord. 2014;19(2):241–7. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-014-0110-y.

Nurkkala M, Kaikkonen K, Vanhala ML, Karhunen L, Keränen A-M, Korpelainen R. Lifestyle intervention has a beneficial effect on eating behavior and long-term weight loss in obese adults. Eat Behav. 2015;18:179–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eatbeh.2015.05.009.

Leblanc V, Begin C, Hudon AM, Royer MM, Corneau L, Dodin S, et al. Gender differences in the long-term effects of a nutritional intervention program promoting the Mediterranean diet: changes in dietary intakes, eating behaviors, anthropometric and metabolic variables. Nutr J. 2014;13:107. https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-2891-13-107.

Miller CK, Kristeller JL, Headings A, Nagaraja H. Comparison of a mindful eating intervention to a diabetes self-management intervention among adults with type 2 diabetes: a randomized controlled trial. Health Educ Behav. 2014;41(2):145–54. https://doi.org/10.1177/1090198113493092.

Carbonneau E, Royer MM, Richard C, Couture P, Desroches S, Lemieux S et al. Effects of the Mediterranean diet before and after weight loss on eating behavioral traits in men with metabolic syndrome. Nutrients. 2017;9(3). doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/nu9030305.

Horbach T, Thalheimer A, Seyfried F, Eschenbacher F, Schuhmann P, Meyer G. abiliti Closed-loop gastric electrical stimulation system for treatment of obesity: clinical results with a 27-month follow-up. Obes Surg. 2015;25(10):1779–87. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-015-1620-z.

Hill BR, Rolls BJ, Roe LS, De Souza MJ, Williams NI. Ghrelin and peptide YY increase with weight loss during a 12-month intervention to reduce dietary energy density in obese women. Peptides. 2013;49:138–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.peptides.2013.09.009.

Arguin H, Tremblay A, Blundell JE, Despres JP, Richard D, Lamarche B, et al. Impact of a non-restrictive satiating diet on anthropometrics, satiety responsiveness and eating behaviour traits in obese men displaying a high or a low satiety phenotype. Br J Nutr. 2017;118(9):750–60. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0007114517002549.

Sanchez M, Darimont C, Panahi S, Drapeau V, Marette A, Taylor VH et al. Effects of a diet-based weight-reducing program with probiotic supplementation on satiety efficiency, eating behaviour traits, and psychosocial behaviours in obese individuals. Nutrients. 2017;9(3). doi:10.3390/nu9030284.

Marlatt KL, Redman LM, Burton JH, Martin CK, Ravussin E. Persistence of weight loss and acquired behaviors 2 y after stopping a 2-y calorie restriction intervention. Am J Clin Nutr. 2017;105(4):928–35. https://doi.org/10.3945/ajcn.116.146837.

Sairanen E, Lappalainen R, Lapvetelainen A, Tolvanen A, Karhunen L. Flexibility in weight management. Eat Behav. 2014;15(2):218–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eatbeh.2014.01.008.

Thomas JG, Bond DS, Phelan S, Hill JO, Wing RR. Weight-loss maintenance for 10 years in the National Weight Control Registry. Am J Prev Med. 2014;46(1):17–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2013.08.019.

Urbanek JK, Metzgar CJ, Hsiao PY, Piehowski KE, Nickols-Richardson SM. Increase in cognitive eating restraint predicts weight loss and change in other anthropometric measurements in overweight/obese premenopausal women. Appetite. 2015;87:244–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2014.12.230.

Gradaschi R, Noli G, Cornicelli M, Camerini G, Scopinaro N, Adami GF. Do clinical and behavioural correlates of obese patients seeking bariatric surgery differ from those of individuals involved in conservative weight loss programme? J Hum Nutr Diet. 2013;26(Suppl 1):34–8. https://doi.org/10.1111/jhn.12080.

Miras AD, Al-Najim W, Jackson SN, McGirr J, Cotter L, Tharakan G, et al. Psychological characteristics, eating behavior, and quality of life assessment of obese patients undergoing weight loss interventions. Scand J Surg. 2015;104(1):10–7. https://doi.org/10.1177/1457496914543977.

Konttinen H, Peltonen M, Sjostrom L, Carlsson L, Karlsson J. Psychological aspects of eating behavior as predictors of 10-y weight changes after surgical and conventional treatment of severe obesity: results from the Swedish Obese Subjects intervention study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2015;101(1):16–24. https://doi.org/10.3945/ajcn.114.095182.

Engström M, Forsberg A, Søvik TT, Olbers T, Lönroth H, Karlsson J. Perception of control over eating after bariatric surgery for super-obesity—a 2-year follow-up study. Obes Surg. 2015;25(6):1086–93. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-015-1652-4.

Laurenius A, Larsson I, Bueter M, Melanson KJ, Bosaeus I, Forslund HB, et al. Changes in eating behaviour and meal pattern following Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Int J Obes. 2011;36:348. https://doi.org/10.1038/ijo.2011.217.

Mack I, Ölschläger S, Sauer H, von Feilitzsch M, Weimer K, Junne F, et al. Does laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy improve depression, stress and eating behaviour? A 4-year follow-up study. Obes Surg. 2016;26(12):2967–73. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-016-2219-8.

Bryant EJ, King NA, Falkén Y, Hellström PM, Juul Holst J, Blundell JE, et al. Relationships among tonic and episodic aspects of motivation to eat, gut peptides, and weight before and after bariatric surgery. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2013;9(5):802–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soard.2012.09.011.

Rieber N, Giel KE, Meile T, Enck P, Zipfel S, Teufel M. Psychological dimensions after laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy: reduced mental burden, improved eating behavior, and ongoing need for cognitive eating control. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2013;9(4):569–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soard.2012.05.008.

Søvik TT, Karlsson J, Aasheim ET, Fagerland MW, Björkman S, Engström M, et al. Gastrointestinal function and eating behavior after gastric bypass and duodenal switch. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2013;9(5):641–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soard.2012.06.006.

Alarcon Del Agua I, Socas-Macias M, Busetto L, Torres-Garcia A, Barranco-Moreno A. Garcia de Luna PP et al. Post-implant analysis of epidemiologic and eating behavior data related to weight loss effectiveness in obese patients treated with gastric electrical stimulation. Obes Surg. 2017;27(6):1573–80. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-016-2495-3.

Petereit R, Jonaitis L, Kupčinskas L, Maleckas A. Gastrointestinal symptoms and eating behavior among morbidly obese patients undergoing Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Medicina. 2014;50(2):118–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.medici.2014.06.009.

Parker K, Mitchell S, O’Brien P, Brennan L. Psychometric evaluation of disordered eating measures in bariatric surgery patients. Eat Behav. 2015;19:39–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eatbeh.2015.05.007.

Bluher M. Obesity: global epidemiology and pathogenesis. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2019;15(5):288–98. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41574-019-0176-8.

Loffler A, Luck T, Then FS, Luppa M, Sikorski C, Kovacs P, et al. Age- and gender-specific norms for the German version of the Three-Factor Eating-Questionnaire (TFEQ). Appetite. 2015;91:241–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2015.04.044.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

All authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Psychological Issues

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Bryant, E.J., Rehman, J., Pepper, L.B. et al. Obesity and Eating Disturbance: the Role of TFEQ Restraint and Disinhibition. Curr Obes Rep 8, 363–372 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13679-019-00365-x

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13679-019-00365-x