Abstract

Faculty diversity is an important driver of student success, especially for students of color. Yet, faculty diversity has not kept pace with the increase in student diversity within US 4-year postsecondary institutions. While students of color make up 42.5% of this population, faculty of color only constitute 24.4%. This study empirically examines these trends in environmental studies departments in California. Using survey data collected from faculty within 22 such departments in the University of California (UC) and California State University (CSU) systems, this study explores the demographic characteristics of faculty in these departments, how these demographics are related to tenure status, and the implications of these results for student success. Importantly, we show that despite students of color constituting 58.2% (UC) and 52.4% (CSU) of the student population within environmental studies departments, faculty of color only represent 22.5% (UC) and 17.7% (CSU) within these departments. These disparities are even more pronounced for Black/African American, Latinx, and Native American populations, which is particularly problematic since many of these schools are Hispanic-Serving Institutions. We conclude that UC and CSU environmental studies departments must take seriously the task of diversifying their faculty and argue that anti-racist training for hiring committees, differentiated support for faculty of color, and creating an inclusive campus climate are key factors for the recruitment and retention of faculty of color.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Faculty diversity is an important driver of student success, especially for students of color. Various studies have pointed to the importance of diverse faculty mentors (Kram 1985; McCoy et al. 2015, 2017; Patton & Harper 2003), full participation and advancement of underrepresented students in academia (Herzig 2006; Stout et al. 2018), and enhanced student success through increased retention (Llamas et al. 2019; Lundberg 2007; Love 2009; Ogundu 2020). Amidst rapid increases in the enrollment of students of color in institutions of higher education, faculty diversity is becoming increasingly important for supporting student learning.Footnote 1 Unfortunately, faculty diversity has not kept pace with the accelerated shift to more diverse student populations over the past few decades (NCES 2003, 2010, 2019). While students of color comprised approximately 42.5% of the student population in US 4-year postsecondary institutions in 2018, faculty of color made up only 24.4% of faculty at these institutions in the same year (NCES 2019). Furthermore, many of these faculty members do not hold tenured or tenure track positions at their institutions (Contreras 2017). This representation gap has important implications for student success in higher education (Herzig 2006; Kram 1985; Lundberg 2007; McCoy et al. 2015, 2017). For instance, students who became closely connected with faculty with a similar racial/ethnic background performed higher academically than those who did not receive the same support (Contreras 2017; Hurtado 2001). These students also grew greater tolerance/acceptance of different cultures and developed leadership skills and greater cultural awareness (Hurtado 2001, p. 198).

Despite both the increase in racial diversity among student populations in 4-year postsecondary US institutions (NCES 2019) and the importance of faculty diversity in supporting these students, little scholarship has examined faculty diversity and its implications for student success in environmental studies and science departments in recent years. In a 2004–2005 survey of environmentally focused academic departments, Dorceta Taylor (2010) found that faculty of color comprised only 11.6% of the sampled environmental studies departments, with 9.4% of those faculty holding non-tenure track positions (compared to 6.9% of white faculty in non-tenure line positions). The absence of more recent data makes it difficult to assess how environmental studies and science departments are adapting to the continued increase in the number of students of color enrolled in higher education (NCES 2019).

This article helps to fill this gap by empirically exploring the diversity among faculty in environmental studies and science departments in California. In order to make the study manageable within the timeframe and funding available, we limited the scope of our inquiry to environmental studies and science departments.Footnote 2 Further, because all co-authors are all members of an environmental studies department (2 undergraduates, 1 PhD student, and 1 faculty member), this focus also allowed us to leverage our existing networks to recruit a large sample within the population. Indeed, our response rate was 54.16% of the 408 surveys we distributed. In addition, we focused on the demographics of University of California (UC) and California State University (CSU) campuses because of increasing student diversity within these institutions and because of California’s reputation for being exceptional in fostering political and social change. As such, a lack of faculty diversity in California public institutions could be a canary in the coal mine for a much broader problem in higher education.

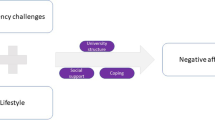

Section “Faculty and student diversity in higher education” provides some empirical background on broad trends in racial composition of students and faculty in higher education. Section “Impact of faculty diversity on student success” then reviews the literature surrounding implications of faculty diversity for student success. Section “Faculty diversity in the UC and CSU environmental studies departments” presents the results of our survey of faculty diversity in environmental studies and science departments within the UC and CSU systems. Together with our literature review, our survey and analysis illuminate (1) the demographic gap between student and faculty populations within UC and CSU environmental studies and science departments, (2) how faculty demographic characteristics are related to tenure status in these departments, and (3) how these inequities undermine the ability of these departments to effectively support student learning, especially for students of color.

Faculty and student diversity in higher education

Enrollment of non-white students in US public 4-year postsecondary institutions has increased from 28.8% in 2001 to 42.5% in 2018 (NCES 2002, 2019). Similar in California, the UC system saw a student-of-color enrollment increase from 46% in 2001 to 56% in 2018 (UC 2020a). The CSU system saw similar trends, with enrollment of students of color increasing from 44.0% in 2001 to 66.0% in 2018 (CFA 2020) (Table 1).

Faculty diversity has not kept pace with student trends. Although faculty diversity has increased over time, the changes are slow compared to those in student demographics over similar time periods (Heilig et al. 2019; Santos et al. 2013; Umbach 2006). The UC and CSU systems have higher percentages of faculty of color than the nationwide average, but these numbers are still lower than the percentages of students of color at these California institutions (see Table 1). Student populations in environmental studies and science departments in UCs and CSUs are similar to institution-wide demographics (Table 2).Footnote 3

These trends are particularly pronounced for faculty from historically underrepresented groups at doctoral-granting institutions (Table 3). For example, between 2001 and 2018, the percentage of faculty members of color at US doctoral-granting institutions (across all departments) has only increased from 3.0 to 5.0% for Hispanic/Latinx faculty and from 5.1 to 5.5% for African American faculty (NCES 2013, 2018).

Impact of faculty diversity on student success

Following Schwarz et al. (2006), our approach to reviewing the literature aims to summarize prior research, critically examine contributions of past research, explain the results of prior research, and clarify differences in alternative views of past research. We aim for “good or reasonable coverage” (Rowe, 2014). We rely on systematicity to facilitate adequate comprehensiveness of our search and to ensure reproducibility of our process.

Faculty diversity and student success

“Student success” describes students’ classroom experiences, academic achievements, and overall well-being. Some sources describe student success using improvements in grades and attrition rates and evaluate how use of more diverse classroom content may lead to advancements in these achievement outcomes (Fairlie 2014; Nagda et al. 1998; Hickson 2002; Hurtado 2001).

In short, the literature demonstrates that racial diversity of faculty is strongly correlated with the success of students of color. Importantly, there is strong evidence that faculty diversity has direct implications for student success for students from minoritized groups in predominantly white institutions (PWIs) (Herzig 2006; Kram 1985; Llamas et al. 2019; Lundberg 2007; Love 2009; McCoy et al. 2015, 2017; Patton & Harper 2003). Various factors contribute to this relationship, including increased mentorship opportunities for students of color in departments with correspondingly diverse faculty (Griffin & Reddick 2011; Love 2009; McCoy et al. 2015; Milner et al. 2002; Figueroa & Rodriguez 2015; Tran et al. 2016). The literature also points to an enhanced classroom experience for students of color in such environments (Fairlie 2014; Nagda et al. 1998; Hickson 2002; Hurtado 2001).

Faculty mentorship

Studies indicate that student-faculty relationships substantially contribute to student success by increasing retention rates, improving overall grades earned, and providing psychosocial support (Castellanos 2016, p. 91; Herzig 2006; Kram 1985; Llamas et al. 2019; Lundberg 2007). Mentorship provided by student-faculty relationships is critical to enhancing classroom experience, academic achievement, and overall well-being for all students and helps students feel more confident, less alienated, and overcome cultural differences (Herzig 2006; Kram 1985; Love 2009; Lundberg 2007; McCoy et al. 2015, 2017; Patton & Harper 2003; Prunuske et al. 2017).

Several studies also highlight that students who are underrepresented in their institutions require more guidance and inclusive practices, which generally are provided by mentorship from faculty of color (Griffin & Reddick 2011; Milner et al. 2002; McCoy et al. 2015; Figueroa & Rodriguez 2015). Faculty diversity helps students of color develop their analytical and critical thinking skills while supporting these students’ career and postgraduate aspirations (Hurtado 2001; McCoy et al. 2017; Umbach 2006; Turner 2015). For example, students at highly selective PWIs across the USA had higher levels of self-reported growth in educational outcomes like critical thinking and problem solving skills when participating in activities that had a more diverse student and faculty population (Hurtado 2001). Additionally, students who were able to learn with faculty from similar racial/ethnic backgrounds were able to grow greater cultural awareness, tolerance of different beliefs, acceptance for people of different backgrounds, and developed leadership skills (Hurtado 2001, p. 198). Moreover, diverse faculty are more likely to teach the significance of diversity, mentor more non-white students, engage with student organizations, and take on sizable mentoring and advising loads (Contreras 2017; Figueroa & Rodriguez 2015; Turner et al. 2008). Solely relying on diverse faculty to uphold these roles is problematic for both faculty and students. Not only does it create disproportionate and often “invisible” labor for faculty of color, which can impede career advancement, but it also implies that students of color may be unable to foster strong mentoring relationships due to a shortage of diverse faculty members. As a result, their access to safe mentoring spaces and academic potential are limited (Contreras 2017; Figueroa & Rodriguez 2015; McCoy et al. 2015; Turner et al. 2008).

Limited opportunities to participate in same-race mentoring relationships with faculty have limited availability of safe mentoring spaces for students of color (Johnson-Bailey & Cervero 2004; McCoy et al. 2017). In these cross-cultural relationships,Footnote 5 studies report that students may not feel comfortable communicating and asking for assistance because trust is harder to gain and sustain (Johnson-Bailey & Cervero 2004; McCoy et al. 2015, 2017). Having role models who share a common experience, culture, language, or history supports students by providing a tangible connection to their college environment (Brisset 2020; Contreras 2017, p. 237). Daniel et al. (2019) explains that even cross-cultural mentoring relationships between two individuals who are both members of different minority cultures present challenges to communication.

Colorblind mentoring—the concept that race does not and should not matter in student-faculty relationships—fails to adequately support students of color because white mentors often lack awareness of white privilege and institutional discrimination against people of color (McCoy et al. 2015; Worthington et al. 2008). For example, a study conducted at two PWIs illuminated how white faculty members in STEM who used a form of colorblind mentoring viewed students of color as academically underprepared and, in turn, assume these students are not interested in research opportunities or in attending graduate school, leading mentors to invest less time with students of color than they do with white students instead of adjusting their mentoring practices to support these students (McCoy et al. 2015). McCoy et al. (2015) further illuminate that these faculty make totalizing claims that students of color are “not top students,” solely discussed cases where students of color were not academically prepared, and even go as far as to say they have less academic prowess than white students and should assimilate to the mainstream campus and departmental cultures in order to succeed (pp. 233–235). While white faculty members acknowledged structural barriers to success that students of color face, such as disparities in K-12 preparation and higher rates of poverty, they did not adjust their mentoring practices to support individual students who face these barriers (McCoy et al. 2015). Further, colorblind mentoring can make students of color feel out of place, especially when mentors have difficulty understanding how students’ backgrounds have manifested in specific challenges (Contreras 2017; Figueroa & Rodriguez 2015, p. 23; Hall and Rowan 2000; McCoy et al. 2015), and the influence of racial bias and hostility on the educational experience of students of color (Griffin & Reddick 2011; Hinton & Seo 2013).

Studies have further shown that more racially and ethnically diverse faculty have a greater ability, in comparison to their white counterparts, to influence and support the academic achievement of students of color (Contreras 2017; Hurtado 2001). Supportive same-race student-faculty relationships are found to be critical for African American/Black students at PWIs, compared to those at historically black colleges and universities (HBCUs), because of the racially hostile environments and campus cultures that African American faculty experienced in their own educational journey (Reddick 2006). These experiences help Black faculty better support learning of Black students because they draw from their own experiences to provide tailored support for their students, who often feel a sense of comfort with same-race mentors (Reddick 2006). Further, professors who attended HBCUs and currently teach at PWIs reported a sense of social responsibility to support African American students after seeing firsthand how having mentors of similar racial backgrounds in their own undergraduate programs helped guide them through racially hostile situations (Reddick, 2006). A similar experience can be seen in Hispanic-Serving Institutions (HSIs), where Latinx students at HSIs report that faculty mentors played a key role in promoting their academic success (Trans et al. 2016).

Classroom experience

Numerous studies at postsecondary institutions throughout the USA show how faculty diversity has contributed to higher retention rates and GPA scores among students of color and has also enhanced learning by offering different teaching methods on critical topics like race and diversity (Fairlie et al. 2014; Llamas et al. 2019; Love 2009). Also contributing to higher passing and retention rates, a diverse faculty exposes students to different pedagogical practices that support diverse learning styles (Fairlie et al. 2014; Hickson 2002; O’Keeffe 2013). Faculty diversity also helps mitigate racial tension on campus, which is negatively correlated with GPA scores (Llamas et al. 2019).

In a national study of 13,499 faculty at 134 colleges and universities, Umbach (2006) found that faculty of color engaged with students in diversity-related issues more frequently than their white counterparts, with the exception of Asian Pacific Americans who were found to be slightly less likely than white faculty to engage in diversity-related topics. Studies show that more diverse teaching methods introduce new perspectives and critical issues to enhance student learning (Abdul-Raheem 2016; Cole et al. 2003; Hurtado 2001; Llamas et al. 2019; Smith 1989). While these practices are beneficial for all students, they are especially important for supporting students of color (Umbach 2006).

Faculty of color can also help to ameliorate gaps in graduation rates (Flores et al. 2017) and other metrics of achievement between white and non-white students. In their study of California community colleges, for example, Fairlie and colleagues (2014) find that student “achievement gaps” for some metrics are reduced by 20–50% with minoritized instructors. They argue that increasing opportunities for within-culture mentorship by increasing the demographic overlap between faculty and student populations and promoting faculty diversity is shown to help minimize these gaps in community college students (Fairlie et al. 2014).

Finally, faculty diversity supports the classroom experiences of students of color by enhancing their sense of belonging. For these students, feeling like they do not belong at a particular institution will make it more difficult to overcome academic challenges (Heisserer and Parette 2002). A sense of belonging is therefore found to be a critical component of college student retention, especially for those at risk of not graduating (O’Keeffe 2013). Because a sense of belonging is directly related to students’ motivation levels and academic ambitions, faculty of color can provide inspiration to fuel student success along these dimensions (Hickson 2002; Hurtado 2001; O’Keeffe 2013).

Tenure, faculty diversity, and student success

It is not just the presence of faculty of color that is important in supporting the success of students of color, but also the security/precarity of those faculty positions. Faculty in secure tenure line positions are more likely to provide support services for students of color, have more autonomy in their teaching practices, and can establish use of different learning practices to better support a growing diverse student population through institutional leadership positions (Antonio 2002; Contreras 2017; Hurtado 2001). Temporary, non-tenure line positions limit faculty from providing these types of services because they lack voting rights within the institution and often suffer from a lack of integration within their departments that would position them to implement changes to curriculum and learning standards (Contreras 2017). Minoritized faculty holding tenure positions therefore have a better platform to advocate for equity among diverse populations and cultivate diversity within the institution (Abdul-Raheem 2016; Contreras 2017).

Faculty of color are underrepresented in tenure line jobs in US postsecondary 2-year and 4-year institutions compared to white faculty (Abdul-Raheem 2016; Contreras 2017; Heilig et al. 2019). Further, even within tenure line positions, minoritized faculty are also less likely to be represented in the higher ranks of full and associate professor than are white faculty (Contreras 2017; CFA 2020). In the CSU system, for example, white (and Asian/Pacific Islander) faculty are overrepresented in the full professor rank, whereas Black, Latinx, and Native American faculty are all underrepresented at this rank (Table 4).

Minority faculty in CSU non-tenure line (lecturer) positions are also more likely to be in entry-level positions (Fig. 4) (Contreras 2017; CFA 2020) (Table 5).

Faculty diversity in the UC and CSU environmental studies departments

Against the backdrop of these broader trends, we conducted a survey to better understand faculty diversity within environmental studies and science departments in the UC and CSU systems. Specifically, the survey collected data from these faculty on place of employment, discipline, race/ethnicity, gender, and job title. This section explains our approach and reports our results.

Sampling

We recruited participants from academic departments across the UC (8 campuses) and CSU (23 campuses) systems. Only departments with the terms “environmental studies” or “environmental science” in the title were chosen. Departments with broader scopes of study were excluded. For example, the Earth and Planetary Sciences Department at UC Santa Cruz was not included in the survey, despite housing an Environmental Sciences major, because of the wide range of majors and courses it offers beyond environmental studies and sciences. As a result of these sampling criteria, several campuses across the UC and CSU systems were excluded from this study including UC Irvine, UC Los Angeles, UC San Diego, CSU Bakersfield, CSU Dominguez Hills, CSU Fullerton, CSU Los Angeles, CSU Maritime Academy, CSU Northridge, CSU Poly Pomona, and CSU Stanislaus. Although this excluded some faculty whose research and teaching is focused on environmental studies and sciences, given our limited capacity (i.e., this research was funded by a summer undergraduate research grant), it was necessary to narrow the scope of our research. All full, associate, assistant, and adjunct professors and lecturers listed on the department websites were recruited for the study. However, as it is likely that some departments do not list all adjunct faculty and lecturers on their department website, this group may be underrepresented by our data set. In total, we recruited 408 faculty and received 221 responses, reflecting a response rate of 54.16%.

Survey design

Google Forms was used to develop and disseminate an online survey. We first asked participants to indicate their institutional affiliation and primary disciplinary training. In order to measure demographic characteristics, participants were asked their racial/ethnic identity and gender identity. Questions about racial/ethnic identity and gender identity were designed using the approaches developed by UC (2010) and the Charles and Lynn Schusterman Family Foundation (2020), respectively.Footnote 6 Questions were slightly modified in order to fit the Google Forms format. To assess the relationship between demographic characteristics and tenure status, we asked participants to report the title of their faculty appointment.

Survey results

Minoritized faculty represent 22.54% (UC) and 17.65% (CSU) of faculty in the sampled environmental studies and science departments in 2020. Of the 102 responses we received from UC faculty, 7.84% (8) were Asian, 3.92% (4) were Black or African American, 2.94%, (3) were Hispanic or Latinx, 7.84% (8) identified as two or more races, and 5.88% (6) chose to self-describe their racial background (Fig. 1). Of the 119 CSU faculty respondents, 5.04% (6) were Asian, 1.68% (2) were Black or African American, 5.04% (6) were Hispanic or Latinx, 4.20% (5) identified as two or more races, and 9.24% (11) chose to self-describe their racial background (Fig. 1). We did not have any responses from Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islanders. American Indian/Alaska Natives made up only 1.68% of the CSU faculty respondents and 0% of responses from UC faculty respondents.

Study limitations

There are of course some limitations to our study design. For example, because we cannot guarantee that our sample is representative, we have only provided descriptive statistics but have not made any claims about statistical significance. We expect, however, that any selection biases would result in a response rate that over samples for faculty of color since, as the literature cited throughout this paper highlights, they tend to have a stronger interest in these issues. Second, in sampling only from environmental studies and environmental science departments, we are likely missing some departments, like geography, which house faculty that work on environmental issues. Further research on this topic can illuminate if such departments experience similar trends. Finally, we would note that we did not collect data on leadership roles, such as department chairs, deans, and/or other important committee leaderships. It would be very interesting and important to illuminate the demographic trends in these positions in future research. Despite these limitations, the study illuminates some critical trends with important implications for student success, which can be built upon and expanded in future research.

UC campus’ non-white faculty respondents represented 12.50% of the total non-tenure line positions and 25.61% of tenure line positions. Of the non-white faculty respondents, 8.70% of responses were lecturers/adjunct professors, 30.43% were assistant professors, 26.09% were associate professors, and 34.78% were full professors. In comparison, among white faculty, 16.44% of respondents were lecturers/adjuncts, 20.55% assistant professors, 16.44% associate professors, 41.09% full professors, and 5.48% responded as “other” (Figs. 2 and 3).

Among CSU respondents, 1.68% (2) of faculty respondents were American Indian or Alaska Native, 5.04% (6) were Asian, 1.68% (2) were Black or African American, 5.04% (6) were Hispanic or Latinx, 73.11% (87) were white, 4.20% (5) identified with two or more races, and 9.24% (11) self-described their raceFootnote 7 (Fig. 4).

Finally, non-white faculty in CSUs made up 17.31% of non-tenure line positions and 23.88% of tenure line positions. Among non-white faculty respondents, 42.86% were lecturers/adjuncts, 19.05% assistant professors, 19.05% associate professors, and 19.05% full professors. Among white faculty respondents, 41.38% were lecturers/adjuncts, 18.39% assistant professors, 9.20% associate professors, and 31.03% full professors (Fig. 5).

Tables 6 and 7 show that faculty of color lag well behind students of color populations in environmental studies and science departments as well.

Conclusions

Although the literature clearly demonstrates that faculty diversity is strongly correlated with success of students of color, minority faculty representation trails far behind student populations in US postsecondary institutions, with this trend being mirrored in environmental studies and science departments in UCs and CSUs (Figueroa & Rodriguez 2015; Griffin & Reddick 2011; Herzig 2006; Milner et al. 2002; Kram 1985; Lundberg 2007) (Tables 6 and 7). The problem is particularly stark when examining only underrepresented groups. US postsecondary institutions (Fig. 6) and UCs (Fig. 7) both have much higher percentages of students, relative to faculty, belonging to Black/African American, Latinx, and Native American/Alaska Native groups. Particularly problematic, the CSU system reports only 10.8% Hispanic/Latinx faculty with a student body composed of 41.5% Hispanic/Latinx students (Fig. 8). This large disparity in representation among students and faculty is particularly concerning, considering 21 of the 23 CSU campuses are designated Hispanic-Serving Institutions.

Student and faculty populations of underrepresented groups in US postsecondary institutions in the fall of 2018 (adapted from NCES, 2019)

Student and faculty populations of underrepresented groups in CSUs in the fall of 2018 (adapted from California Faculty Association, 2020)

Further, minoritized faculty members are underrepresented in tenure line positions, especially at the higher ranks. This is problematic because tenure status provides security for faculty to advocate for equity within academic institutions and for learning practices that support diverse student populations (Antonio 2002; Contreras 2017; Hurtado 2001). As such, not only are students of color not receiving the support they need, but faculty of color are not institutionally enabled to provide it.

The UC Accountability report argues that a “limited availability of candidates” is a significant source of this problem (UC 2020d, p. 90). However, there is plenty of research that refutes this claim (Griffin 2019). For example, several studies have examined the reasons why minoritized faculty members are underrepresented in tenure line positions and in higher ranks. Explanations include bias during both the hiring (Sensoy & Diangelo 2017; Smith et al. 2004) and the tenure and promotion (Baez 2000; Sensoy & Diangelo 2017; Turner et al. 2008) processes. For example, studies have illuminated how implicit bias during the hiring process for tenure line positions is reflected in hiring committees’ tendency to overscrutinize qualifications and credentials of minoritized applicants (Sensoy & Diangelo 2017; Smith et al. 2004). Others have demonstrated the consistent undervaluing of faculty of color productivity in the promotion process, which, in turn, leads to retention problems (Jayakumar et al. 2009; Writer and Watson 2019). Several other studies point to the role of service obligations in the promotion process for tenure line faculty (Brayboy 2003; Baez 2000; Brissett 2020; Sensoy & Diangelo 2017). Minoritized faculty are more likely to engage in mentoring and supporting a growing body of minoritized students, which is often undervalued compared to research and teaching, underscoring how the contributions and qualifications of faculty of color are often depreciated within their institutions (Baez 2000; Green 2008; Menges and Exum 1983; Sensoy & Diangelo 2017; Youn & Price 2009).

The existing literature on the links between faculty diversity and student achievement, coupled with the results of our survey analysis, suggest that environmental studies and science departments should prioritize hiring, promoting, and retaining faculty of color. This means, at a minimum, engaging in anti-bias and anti-racist training for faculty and administrators who make such hiring and promotion decisions, and critically examining and repairing existing practices and norms that guide these processes. One promising trend is the recent use of “diversity first” searches wherein hiring committees make their first cut of an applicant pool based on evaluation of diversity statements. This practice signals that diversity criterion is an essential component of a candidate’s application and can yield dividends in departmental culture and climate over time as the departmental make-up changes. However, recruiting faculty of color is just the first step. They also must be retained. This requires creating a culture of inclusivity and ensuring that faculty of color feel valued and respected. For many departments and universities, this will require introspective work that will likely challenge dominant and long-standing norms. Importantly, institutions that are serious about attracting and retaining faculty of color must reject past “color-blind” practices and become quickly comfortable with programs of differentiated support that actively seek to support faculty of color, especially those from underrepresented backgrounds and those who are relatively underrepresented in comparison to student populations.Footnote 8

It is important to consider the limitations of reformist approaches. We advocate for recruitment and retention of faculty of color as a strategy for supporting the well-being of students of color and for enhancing the educational experience of all students. However, we also recognize that the inequities in higher education may not be remedied by incremental change nor large-scale reform. A growing number of critical scholarly perspectives on US institutions of higher education illustrate how these institutions are inherently structured as sites of anti-Black racism, Indigenous genocide, and other forms of violence against minority students (Grande 2018; Kelley 2016; Moten and Harney 2004; Rodriguez 2012; Wilder 2014). As a result, we cannot expect university reform—however inclusive—to fully support the needs of all students. Furthermore, while there has been little research on faculty diversity in environmental studies and science departments specifically, it is well known that faculty diversity in higher education is particularly low in STEM fields (Hill et al. 2011). For example, a UC study of diversity of ladder rank faculty by discipline reports a lower percentage and slower growth rate of “domestic underrepresented racial/ethnic groups” in STEM fields when compared to Arts and Humanities, Social Science and Psychology, and Education fields (UCOP 2018).

As a result, the notable lack of diverse representation within environmental studies and science departments cannot solely be attributed to the structural conditions of higher education but must also be considered in the context of the formation of our discipline and of US environmental movements more broadly. Environmental justice scholars and activists have long critiqued whiteness, masculinity, and other forms of domination/oppression within the mainstream US environmental movement and discussed alternatives (e.g., Agyeman 2005; Martinez-Alier 2003; Pellow 2004; Pulido 1996; Schlosberg 1999, 2007). These critiques must be taken seriously by those seeking to create more equitable spaces of environmental education to address the ways in which the mainstream US environmental movement informs department culture in the environmental studies and science.

While we argue for the recruitment and retention of underrepresented faculty as a strategy for supporting the immediate needs of underrepresented students, we do so with an eye toward the more transformative possibilities advocated by student activists, critical education scholars, and environmental justice scholars and activists. This includes (but is not limited to) the creation of grassroots (environmental) educational projects that support diverse people and perspectives beyond the university setting (Undercommoning 2021) and subversion within the university, whereby students, faculty, and other community members expose and resist the university’s violence while simultaneously using the space to learn about and envision alternatives (Moten and Harney 2004).

Data Availability

All document-based data are publicly available online. Aggregated survey data are available from the authors upon request.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Notes

We discuss faculty diversity here primarily along the dimension of race because this has been shown to be a particularly important dimension for supporting students of color.

Sampled departments were any in the UC or CSU systems which used the word “Environmental Studies” or “Environmental Science” in their names. We recognize this excluded, for example, environmental science concentrations within departments with other names. However, due to funding constraints, we chose to sample in this way.

Not all campuses surveyed had department-level student demographics publicly available. Schools included are UCD, UCB, UCSC, UCSB, UCR, HSU, CSU, CSUEB, SFSU, SJSU, CSUCI, CSUSB, and CSUSM.

Cross-cultural relationships are those between individuals with cultural, racial, and/or regional differences in their background, experiences, and identities (Daniel et al. 2019).

Rather than using census data, we chose to use UC data because of its immediate relevance to our study. We additionally drew from the Charles and Lynn Schusterman Family Foundation’s (2020) More than Numbers: Guide Toward Diversity, Equity and Inclusion (DEI) in Data Collection to critically frame our survey questions with attention to the ways that dominant constructions and categorizations of race and gender can “unintentionally reinforce harmful stereotypes and perpetuate inequity and bias” (p. 4).

Self-descriptions included responses indicating multiethnic or multicultural backgrounds, European descent, or specified nations of origin, and multiple responses identifying as white in appearance but not in cultural background.

References

Abdul-Raheem, J. (2016). Faculty diversity and tenure in higher education. Journal of Cultural Diversity, 23(2)

Agyeman, J. (2005). Sustainable communities and the challenge of environmental justice. New York University Press

Antonio AL (2002) Faculty of color reconsidered: reassessing contributions to scholarship. The Journal of Higher Education 73:582–602. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221546.2002.11777169

Baez B (2000) Race-related service and faculty of color: conceptualizing critical agency in academe. High Educ 39(3):363–391

Brayboy BM (2003) The implementation of diversity in predominantly white colleges and universities. J Black Stud 34(1):72–86. https://doi.org/10.1177/0021934703253679

Brent Berry & Eduardo Bonilla-Silva (2008) ‘They should hire the one with the best score’: white sensitivity to qualification differences in affirmative action hiring decisions. Ethn Racial Stud 31(2):215–242. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870701337619

Brissett N (2020) Inequitable rewards: experiences of faculty of color mentoring students of color. Mentoring & Tutoring: Partnership in Learning 28(5):556–577. https://doi.org/10.1080/13611267.2020.1859327

Bonilla-Silva, E. (2006). Racism without racists: color-blind racism and the persistence of racial inequality in the United States. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers

Burke MA (2016) New frontiers in the study of color-blind racism: a materialist approach. Social Currents 3(2):103–109

California Faculty Association. (2020). Changing faces of the CSU faculty and students. Volume VIII [PDF]

Castellanos J, Gloria AM, Besson D, Harvey LOC (2016) Mentoring matters: racial ethnic minority undergraduates’ cultural fit, mentorship, and college and life satisfaction. Journal of College Reading and Learning 46(2):81–98. https://doi.org/10.1080/10790195.2015.1121792

Charles and Lynn Schusterman Family Foundation (2020) More than numbers: a guide toward diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) in data collection. Retrieved from: https://www.schusterman.org/sites/default/files/DEIDataCollectionGuide.pdf. Accessed 22 Mar 2022

Chico State University (CSU) (2021) Census enrollment graph. Retrieved from https://wildcats-bi-ext.csuchico.edu/t/InstitutionalResearch/views/Enrollment_0/EnrollmentataGlance?iframeSizedToWindow=true&%3Aembed=y&%3AshowAppBanner=false&%3Adisplay_count=no&%3AshowVizHome=no. Accessed 22 Mar 2022

Cole S, Barber EG, Barber EG (2003) Increasing faculty diversity: the occupational choices of high-achieving minority students. ProQuest Ebook Central https://ebookcentral-proquest-com.oca.ucsc.edu. Accessed 22 Mar 2022

Contreras F (2017) Latino faculty in Hispanic-Serving Institutions: where is the diversity? Association of Mexican American Educators Journal 11:223. https://doi.org/10.24974/amae.11.3.368

CSU Channel Islands (CSUCI) (2021) Fall enrollment: enrollment trends by student characteristics. Retrieved from https://oneci.csuci.edu/t/IRPEGuest/views/FallEnrollmentpublic/EnrollmentDashboard?:iid=1&:isGuestRedirectFromVizportal=y&:embed=y. Accessed: 22 Mar 2022

CSU East Bay (CSUEB) (2021) Program enrollment. Retrieved from https://data.csueastbay.edu/#/apr/program_data/program_enrollment. Accessed 22 Mar 2022

CSU San Bernardino (CSUSB) (2021) Enrollment Dashboard. Retrieved from https://tableau.calstate.edu/views/SelfEnrollmentDashboard/EnrollmentSummary?iframeSizedToWindow=true&%3Aembed=y&%3AshowAppBanner=false&%3Adisplay_count=no&%3AshowVizHome=no. Accessed 22 Mar 2022

CSU San Marcos (CSUSM) (2021) Detailed enrollment breakdown - total headcount. Retrieved from https://tableau.csusm.edu/views/StudentProfile_0/EnrollmentTrends?%3Aembed=y&%3AshowShareOptions=true&%3Adisplay_count=no&%3AshowVizHome=no%20. Accessed 22 Mar 2022

Daniel A, Franco S, N. L. & Cenkci A. T. (2019) Cross-cultural academic mentoring dyads: a case study. Mentoring & Tutoring: Partnership in Learning 27(2):164–189. https://doi.org/10.1080/13611267.2019.1611286

Fairlie RW, Hoffmann F, Oreopoulos P (2014) A community college instructor like me: race and ethnicity interactions in the classroom. American Economic Review 104(8):2567–2591

Figueroa JL, Rodriguez GM (2015) Critical mentoring practices to support diverse students in higher education: Chicana/Latina faculty perspectives. N Dir High Educ 2015:23–32. https://doi.org/10.1002/he.20139

Flores SM, Park TJ, Baker DJ (2017) The racial college completion gap: evidence from Texas. The Journal of Higher Education 88(6):894–921

Grande, S. (2018). Refusing the university. Toward what justice, 47–65

Green RG (2008) Tenure and promotion decisions: the relative importance of teaching, scholarship, and service. J Soc Work Educ 44(2):117–128. https://doi.org/10.5175/jswe.2008.200700003

Griffin, K. A. (2019). Institutional barriers, strategies, and benefits to increasing the representation of women and men of color in the professoriate. Higher Education: Handbook of Theory and Research, 1-73. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-11743-6_4-1

Griffin K, Reddick R (2011) Surveillance and sacrifice: gender differences in the mentoring patterns of black professors at predominantly white research universities. Am Educ Res J 48(5):1032–1057. https://doi.org/10.2307/41306377

Hall R, Rowan G (2000) African American males in higher education: a descriptive/qualitative analysis. Journal of African American Men 5(3):3–14. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/41819402. Accessed 22 Mar 2022

Heilig JV, Flores IW, Barros Souza AE, Barry JC, Monroy SB (2019) Considering the ethnoracial and gender diversity of faculty in United States college and university intellectual communities. Hisp. JL & Pol'y, 1

Heisserer DL, Parette P (2002) Advising at-risk students in college and university settings. College Student Journal 36(1):69–84

Hickson MG (2002) What role does the race of professors have on the retention of students attending historically black colleges and universities? Education 123(1):186–190

Hill PL, Shaw RA, Taylor JR, Hallar BL (2011) Advancing diversity in STEM. Innovative Higher Education 36(1):19–27

Hinton D, Seo BI (2013) Culturally relevant pedagogy and its implications for retaining minority students in predominantly white institutions (PWIs). In: The stewardship of higher education (pp. 133–148). Brill Sense

Herzig AH (2006) How can women and students of color come to belong in graduate mathematics? In: Bystydzienski JM (ed) Removing barriers: women in academic science, technology, engineering, and mathematics. Indiana University Press, Bloomington, IN, pp 254–270

Humboldt State University (HSU) (2020a) Environmental studies program enrollment. Retrieved from http://pine.humboldt.edu/anstud/cgi-bin/filter.pl?relevant=./progdata/programs/majors_overview_EST.out. Accessed 22 Mar 2022

Humboldt State University (HSU) (2020b) Environmental science and management program enrollment. Retrieved from http://pine.humboldt.edu/anstud/cgi-bin/filter.pl?relevant=./progdata/programs/majors_overview_ESM.out. Accessed 22 Mar 2022

Hurtado S, Alvarado AR (2012) The climate for underrepresented groups and diversity on campus.

Hurtado S (2001) Linking diversity with educational purpose: how the diversity impacts the classroom environment and student development. In: Orfield G (ed) Diversity challenged: legal crisis and new evidence. Harvard Publishing Group, Cambridge, MA, pp 187–203

Jayakumar UM, Howard TC, Allen WR, Han JC (2009) Racial privilege in the professoriate: an exploration of campus climate, retention, and satisfaction. The Journal of Higher Education 80(5):538–563

Johnson-Bailey J, Cervero RM (2004) Mentoring in black and white: the intricacies of cross-cultural mentoring. Mentoring & Tutoring: Partnership in Learning 12(1):7–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/1361126042000183075

Kelley RD (2016) Black study, black struggle. Boston Review (March 7)

Kram KE (1985) Mentoring at work. Developmental relationships in organizational life. Scott Foresman & Company, Glenview, IL

Llamas JD, Nguyen K, Tran AGTT (2019) The case for greater faculty diversity: examining the educational impacts of student-faculty racial/ethnic match. Race Ethn Educ. https://doi.org/10.1080/13613324.2019.1679759

Love D (2009) Student retention through the lens of campus climate, racial stereotypes, and faculty relationships. Journal of Diversity Management (JDM) 4(3):21–26. https://doi.org/10.19030/jdm.v4i3.4962

Lundberg CA (2007) Student involvement and institutional commitment to diversity as predictors of Native American student learning. J Coll Stud Dev 48(4):405–416. https://doi.org/10.1353/csd.2007.0039

Martinez-Alier, J. (2003). The environmentalism of the poor: a study of ecological conflicts and valuation. Edward Elgar Publishing

McCoy DL, Winkle-Wagner R, Luedke CL (2015) Colorblind mentoring? Exploring white faculty mentoring of students of color. Journal of Diversity in Higher Education 8(4):225–242. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0038676

McCoy DL, Luedke CL, Winkle-Wagner R (2017) Encouraged or weeded out: perspectives of students of color in the STEM disciplines on faculty interactions. J Coll Stud Dev 58(5):657–673. https://doi.org/10.1353/csd.2017.0052

Brayboy MJ, B. (2003) The implementation of diversity in predominantly white colleges and universities. J Black Stud 34(1):72–86

Menges RJ, Exum WH (1983) Barriers to the progress of women and minority faculty. The Journal of Higher Education 54(2):123–144

Milner HR, Husband T, Jackson MP (2002) Voices of persistence and self-efficacy: African American graduate students and professors who affirm them. Journal of Critical Inquiry into Curriculum and Instructions 4:33–39

Moten F, Harney S (2004) The university and the undercommons: Seven theses. Social Text 22(2):101–115

Nagda BA, Gregerman SR, Jonides J, von Hippel W, Lerner JS (1998) Undergraduate student-faculty research partnerships affect student retention. Rev High Educ 22(1):55–72. https://doi.org/10.1353/rhe.1998.0016

National Center for Education Statistics (NCES) (2012) Digest of education statistics.

National Center for Education Statistics (NCES) (2002) Digest of education statistics. https://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/2002menu_tables.asp. Accessed 22 Mar 2022

National Center for Education Statistics (NCES) (2003) Digest of education statistics. https://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d03/tables/dt231.asp. Accessed 22 Mar 2022

National Center for Education Statistics (NCES) (2010) Digest of education statistics. https://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d10/tables/dt10_235.asp. Accessed 22 Mar 2022

National Center for Education Statistics (NCES) (2013) Digest of education statistics. https://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/2013menu_tables.asp. Accessed 22 Mar 2022

National Center for Education Statistics (NCES) (2018) Digest of education statistics. https://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/2018menu_tables.asp. Accessed 22 Mar 2022

National Center for Education Statistics (NCES) (2019) Digest of education statistics. https://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d19/tables/dt19_315.20.asp?current=yes. Accessed 22 Mar 2022

Ogundu TN (2020) Correlations between faculty and student diversity and student retention rates in two-year public colleges. (Doctoral dissertation, Grand Canyon University)

O’Keeffe P (2013) A sense of belonging: improving student retention. College Student Journal 47(4):605+. https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/A356906575/CWI?u=ucsantacruz&sid=CWI&xid=f3e94c30. Accessed 22 Mar 2022

Patton LD, Harper SR (2003) Mentoring relationships among African American women in graduate and professional schools. New Dir Stud Serv 2003:67–78. https://doi.org/10.1002/ss.108

Pellow DN (2004) Garbage wars: the struggle for environmental justice in Chicago. MIT Press

Prunuske, A., Sciences, D., Wilson, J., Sociology/Anthropology, D., Walls, M., Department of Biobehavioral and Population Health, . . . Williams, S. (2017, October 13). Efforts at broadening participation in the sciences: an examination of the mentoring experiences of students from underrepresented groups. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1187/cbe.16-01-0024

Pulido L (1996) Environmentalism and economic justice: two Chicano struggles in the Southwest. University of Arizona Press

Reddick RJ (2006) The gift that keeps giving: historically black college and university-educated scholars and their mentoring at predominately white institutions. Educ Found 20:61–84

Rodríguez D (2012) Racial/colonial genocide and the “neoliberal academy”: in excess of a problematic. Am Q 64(4):809–813

Rowe F (2014) What literature review is not: diversity, boundaries and recommendations.

Sacramento State University (SSU) (2021) Enrollment dashboard. Retrieved from https://www.csus.edu/president/institutional-research-effectiveness-planning/dashboards/enrollment.html. Accessed 22 Mar 2022

San Francisco State University (SFSU) (2021) San Francisco State University total enrollment: student enrollment report. Retrieved from https://webfocus.sfsu.edu/ibi_apps/run.bip?BIP_REQUEST_TYPE=BIP_RUN&BIP_folder=IBFS%3A%2FWFC%2FRepository%2FIR_Public%2FEnrollment&BIP_item=Enrollment.htm&windowHandle=975697&IBI_random=3725.1320518559305. Accessed 22 Mar 2022

San Jose State University (SJSU) (2021) Enrollment by demographics. Retrieved from http://www.iea.sjsu.edu/Students/Enrollment/enroll_demographics.php. Accessed 22 Mar 2022

Santos JL, Acevedo-Gil N (2013) A report card on Latina/o leadership in California’s public universities: a trend analysis of faculty, students, and executives in the CSU and UC systems. J Hisp High Educ 12(2):174–200

Schlosberg, D. (1999). Environmental justice and the new pluralism: the challenge of difference for environmentalism. OUP Oxford

Schlosberg, D. (2007). Defining environmental justice: theories, movements, and nature. OUP Oxford

Schwarz A, Metha M, Johnson N, Chin W (2006) Understanding frameworks and reviews: a commentary to assist us in moving our field forward by analyzing our past. Database for Advances in Information Systems 38(3):29–50

Sensoy, Ö, & Diangelo, R. (2017). “We Are All for Diversity, but . . .”: how faculty hiring committees reproduce whiteness and practical suggestions for how they can change. Harvard Educational Review, 87(4), 557–580. https://doi.org/10.17763/1943-5045-87.4.557

Smith DG (1989) The Challenge of Diversity. Involvement or Alienation in the Academy? ASHE-ERIC Higher Education Report No. 5, 1989. ASHE-ERIC Higher Education Reports, The George Washington University, One Dupont Circle, Suite 630, Dept. ES, Washington, DC 20036-1181

Smith DG, Turner CS, Osei-Kofi N, Richards S (2004) Interrupting the usual: successful strategies for hiring diverse faculty. The Journal of Higher Education 75(2):133–160. https://doi.org/10.1353/jhe.2004.0006

Stout R, Archie C, Cross D, Carman CA (2018) The relationship between faculty diversity and graduation rates in higher education. Intercult Educ 29(3):399–417

Taylor, D.E. (2010), Race, gender, and faculty diversity in environmental disciplines. In: Taylor, D.E. (Ed.) Environment and social justice: an international perspective (Research in social problems and public policy, Vol. 18), Emerald Group Publishing Limited, Bingley, pp. 385–407

Tran NA, Jean-Marie G, Powers K, Bell S, Sanders K (2016) Using institutional resources and agency to support graduate students’ success at a Hispanic serving institution. Education Sciences 6(3):28

Turner CS, González JC, Wood JL (2008) Faculty of color in academe: what 20 years of literature tells us. Journal of Diversity in Higher Education 1(3):139–168. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0012837

Turner, C. S 2015 Mentoring as transformative practice: supporting student and faculty diversity. Jossey-Bass

Worthington RL, Navarro RL, Loewy M, Hart J (2008) Color-blind racial attitudes, social dominance orientation, racial-ethnic group membership and college students’ perceptions of campus climate. Journal of Diversity in Higher Education 1(1):8–19. https://doi.org/10.1037/1938-8926.1.1.8

UC Berkeley (UCB) (2019) Student headcount by major and demographics. Retrieved from https://pages.github.berkeley.edu/OPA/our-berkeley/student-headcount-by-major.html. Accessed 22 Mar 2022

UC Davis (UCD) (2021) STEM demographics. Retrieved from https://aggiedata.ucdavis.edu/. Accessed 22 Mar 2022

UC Riverside (UCR) (2021) Enrollment: programs - fall headcount. Retrieved from https://ir.ucr.edu/enrollments-programs. Accessed 22 Mar 2022

UC Santa Cruz (UCSC) (2019) 2019 fall quarter undergraduate major count by ethnicity. Retrieved from https://mediafiles.ucsc.edu/iraps/student-majors/fall-term/2019-20/fall-undergraduate-majorsbyethnicity-mc-87643.pdf. Accessed 22 Mar 2022

Umbach PD (2006) The contribution of faculty of color to undergraduate education. Res High Educ 47:317–345. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11162-005-9391-3

Undercommoning (2021) Gallery of alternatives archives. Retrieved from http://undercommoning.org/category/alternatives/. Accessed 22 Mar 2022

University of California Office of the President (UCOP). 2018. Accountability sub-report on diversity: faculty diversity outcomes. Accessed December 3, 2021, at https://regents.universityofcalifornia.edu/regmeet/sept18/a2.pdf (Accessed: 22 March 2022)

University of California (UC) (2010) FAQ on new ethnicity and race categories for UC. Retrieved from https://ucnet.universityofcalifornia.edu/tools-and-services/administrators/docs/frequently-asked-questions.pdf. Accessed 22 Mar 2022

University of California (UC) (2020a, October 23) Fall enrollment at a glance. Retrieved from https://www.universityofcalifornia.edu/infocenter/fall-enrollment-glance. Accessed 22 Mar 2022

University of California (UC) (2020b, October 23) Workforce diversity. Retrieved from https://www.universityofcalifornia.edu/infocenter/uc-workforce-diversity. Accessed 22 Mar 2022

University of California (UC) (2020c) Accountability report 2020c. Retrieved from https://accountability.universityofcalifornia.edu/2020/welcome.html. Accessed 22 Mar 2022

University of California (UC) (2020d) University of California Accountability Report | 5: Faculty and Other Academic Employees. Available at: https://accountability.universityofcalifornia.edu/2020/chapters/chapter-5.html#5.2.1. Accessed 17 Feb 2021

Wilder CS (2014) Ebony and ivy: race, slavery, and the troubled history of America’s universities. Bloomsbury Publishing USA

Writer JH, Watson DC (2019) Recruitment and retention: an institutional imperative told through the storied lenses of faculty of color. Journal of the Professoriate 10(2):23–46

Youn TI, Price TM (2009) Learning from the experience of others: the evolution of faculty tenure and promotion rules in comprehensive institutions. The Journal of Higher Education 80(2):204–237. https://doi.org/10.1353/jhe.0.0041

Acknowledgements

This project was funded by a Building Belonging Program grant from the Institute for Social Transformation at the University of California Santa Cruz. We are grateful to Enrico Ramirez-Ruiz for his thoughtful comments on an earlier draft of this manuscript.

Funding

This research project was funded through the Building Belonging Program. This program is offered through the Institute for Social Transformation in the Division of Social Sciences at the University of California Santa Cruz.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

The Office of Research Compliance Administration has determined that the Human Subject Research Protocol used in this study meets the criteria for exemption described in 45 CFR 46.104 and/or the UCSC Policy on IRB Regulatory Flexibility under “Exempt 2”. UCSC IRB operates under the Federalwide Assurance approved by the DHHS Office for Human Research Protections, FWA00002797; the DHHS IRB Registration Number is IRB00000266.

Consent to participate

The Human Subjects Research Protocol used in this study (IRB# HS3732) was granted exemption.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Taylor, A.M., Hernandez, A.J., Peterson, A.K. et al. Faculty diversity in California environmental studies departments: implications for student learning. J Environ Stud Sci 12, 490–504 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13412-022-00755-z

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13412-022-00755-z