Abstract

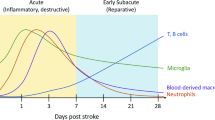

Microglia/macrophages (M) are major contributors to postinjury inflammation, but they may also promote brain repair in response to specific environmental signals that drive classic (M1) or alternative (M2) polarization. We investigated the activation and functional changes of M in mice with traumatic brain injuries and receiving intracerebroventricular human bone marrow mesenchymal stromal cells (MSCs) or saline infusion. MSCs upregulated Ym1 and Arginase-1 mRNA (p < 0.001), two M2 markers of protective M polarization, at 3 and 7 d postinjury, and increased the number of Ym1+ cells at 7 d postinjury (p < 0.05). MSCs reduced the presence of the lysosomal activity marker CD68 on the membrane surface of CD11b-positive M (p < 0.05), indicating reduced phagocytosis. MSC-mediated induction of the M2 phenotype in M was associated with early and persistent recovery of neurological functions evaluated up to 35 days postinjury (p < 0.01) and reparative changes of the lesioned microenvironment. In vitro, MSCs directly counteracted the proinflammatory response of primary murine microglia stimulated by tumor necrosis factor-α + interleukin 17 or by tumor necrosis factor-α + interferon-γ and induced M2 proregenerative traits, as indicated by the downregulation of inducible nitric oxide synthase and upregulation of Ym1 and CD206 mRNA (p < 0.01). In conclusion, we found evidence that MSCs can drive the M transcriptional environment and induce the acquisition of an early, persistent M2-beneficial phenotype both in vivo and in vitro. Increased Ym1 expression together with reduced in vivo phagocytosis suggests M selection by MSCs towards the M2a subpopulation, which is involved in growth stimulation and tissue repair.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Lingsma HF, Roozenbeek B, Steyerberg EW, Murray GD, Maas AIR. Early prognosis in traumatic brain injury: from prophecies to predictions. Lancet Neurol 2010;9:543-554.

Xiong Y, Mahmood A, Chopp M. Neurorestorative treatments for traumatic brain injury. Discov Med 2010;10:434-442.

Christie KJ, Turnley AM. Regulation of endogenous neural stem/progenitor cells for neural repair-factors that promote neurogenesis and gliogenesis in the normal and damaged brain. Front Cell Neurosci 2012;6:70.

Xiong Y, Mahmood A, Meng Y, et al. Delayed administration of erythropoietin reducing hippocampal cell loss, enhancing angiogenesis and neurogenesis, and improving functional outcome following traumatic brain injury in rats: comparison of treatment with single and triple dose. J Neurosurg 2010;113:598-608.

Loane DJ, Faden AI. Neuroprotection for traumatic brain injury: translational challenges and emerging therapeutic strategies. Trends Pharmacol Sci 2010;31:596-604.

Maas AIR, Stocchetti N, Bullock R. Moderate and severe traumatic brain injury in adults. Lancet Neurol 2008;7:728-741.

Ohtaki H, Ylostalo JH, Foraker JE, et al. Stem/progenitor cells from bone marrow decrease neuronal death in global ischemia by modulation of inflammatory/immune responses. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2008;105:14638-14643.

Sarnowska A, Braun H, Sauerzweig S, Reymann KG. The neuroprotective effect of bone marrow stem cells is not dependent on direct cell contact with hypoxic injured tissue. Exp Neurol 2009;215:317-327.

Zanier ER, Montinaro M, Vigano M, et al. Human umbilical cord blood mesenchymal stem cells protect mice brain after trauma. Crit Care Med 2011;39:2501-2510.

Nakajima H, Uchida K, Guerrero AR, et al. Transplantation of mesenchymal stem cells promotes an alternative pathway of macrophage activation and functional recovery after spinal cord injury. J Neurotrauma 2012;29:1614-1625.

Kumar A, Loane DJ. Neuroinflammation after traumatic brain injury: Opportunities for therapeutic intervention. Brain Behav Immun 2012;26:1191-1201.

Kumar A, Stoica BA, Sabirzhanov B, Burns MP, Faden AI, Loane DJ. Traumatic brain injury in aged animals increases lesion size and chronically alters microglial/macrophage classical and alternative activation states. Neurobiol Aging 2013;34:1397-1411.

Shechter R, Schwartz M. Harnessing monocyte-derived macrophages to control central nervous system pathologies: no longer “if” but “how”. J Pathol 2013;229:332-346.

Lai AY, Todd KG. Differential regulation of trophic and proinflammatory microglial effectors is dependent on severity of neuronal injury. Glia 2008;56:259-270.

Madinier A, Bertrand N, Mossiat C, et al. Microglial involvement in neuroplastic changes following focal brain ischemia in rats. PLoS ONE 2009;4:e8101.

Kigerl KA, Gensel JC, Ankeny DP, Alexander JK, Donnelly DJ, Popovich PG. Identification of two distinct macrophage subsets with divergent effects causing either neurotoxicity or regeneration in the injured mouse spinal cord. J Neurosci 2009;29:13435-13444.

Longhi L, Perego C, Ortolano F, et al. Tumor necrosis factor in traumatic brain injury: effects of genetic deletion of p55 or p75 receptor. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2013;33:1182-1189.

Chhor V, Le Charpentier T, Lebon S, et al. Characterization of phenotype markers and neuronotoxic potential of polarised primary microglia in vitro. Brain Behav Immun 2013;32:70-85.

Hu X, Li P, Guo Y, et al. Microglia/macrophage polarization dynamics reveal novel mechanism of injury expansion after focal cerebral ischemia. Stroke 2012;43:3063-3070.

Fumagalli S, Perego C, Ortolano F, De Simoni M-G. CX3CR1 deficiency induces an early protective inflammatory environment in ischemic mice. Glia 2013;61:827-842.

Pischiutta F, D’Amico G, Dander E, et al. Immunosuppression does not affect human bone marrow mesenchymal stromal cell efficacy after transplantation in traumatized mice brain. Neuropharmacology 2014;79:119-126.

Dander E, Lucchini G, Vinci P, et al. Mesenchymal stromal cells for the treatment of graft-versus-host disease: understanding the in vivo biological effect through patient immune monitoring. Leukemia 2012;26:1681-1684.

Zanier ER, Pischiutta F, Villa P, et al. Six-month ischemic mice show sensorimotor and cognitive deficits associated with brain atrophy and axonal disorganization. CNS Neurosci Ther 2013;19:695-704.

Ortolano F, Colombo A, Zanier ER, et al. c-Jun N-terminal kinase pathway activation in human and experimental cerebral contusion. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 2009;68:964-971

Paxinos G, Franklin KBJ. The mouse brain in stereotaxic coordinates. Academic Press, San Diego, CA, USA, 2004.

Capone C, Frigerio S, Fumagalli S, et al. Neurosphere-derived cells exert a neuroprotective action by changing the ischemic microenvironment. PLoS ONE 2007;2:e373.

Donnelly DJ, Gensel JC, Ankeny DP, van Rooijen N, Popovich PG. An efficient and reproducible method for quantifying macrophages in different experimental models of central nervous system pathology. J Neurosci Methods 2009;181:36-44.

Schindelin J, Arganda-Carreras I, Frise E, et al. Fiji: an open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nat Methods 2012;9:676-682.

Gesuete R, Storini C, Fantin A, et al. Recombinant C1 inhibitor in brain ischemic injury. Ann Neurol 2009;66:332-342.

Curtis R, Hardy R, Reynolds R, Spruce BA, Wilkin GP. Down-regulation of GAP-43 During Oligodendrocyte Development and Lack of Expression by Astrocytes In Vivo: Implications for Macroglial Differentiation. Eur J Neurosci 1991;3:876-886.

Riglar DT, Rogers KL, Hanssen E, et al. Spatial association with PTEX complexes defines regions for effector export into Plasmodium falciparum-infected erythrocytes. Nat Commun 2013;4:1415.

Longhi L, Perego C, Ortolano F, et al. C1-inhibitor attenuates neurobehavioral deficits and reduces contusion volume after controlled cortical impact brain injury in mice. Crit Care Med 2009;37:659-665.

Verderio C, Muzio L, Turola E, et al. Myeloid microvesicles are a marker and therapeutic target for neuroinflammation. Ann Neurol 2012;72:610-624.

Stein VM, Baumgärtner W, Schröder S, Zurbriggen A, Vandevelde M, Tipold A. Differential expression of CD45 on canine microglial cells. J Vet Med A Physiol Pathol Clin Med 2007;54:314-320.

Perego C, Fumagalli S, De Simoni M-G. Temporal pattern of expression and colocalization of microglia/macrophage phenotype markers following brain ischemic injury in mice. J Neuroinflammation 2011;8:174.

Ramprasad MP, Terpstra V, Kondratenko N, Quehenberger O, Steinberg D. Cell surface expression of mouse macrosialin and human CD68 and their role as macrophage receptors for oxidized low density lipoprotein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1996;93:14833-14838

Kurushima H, Ramprasad M, Kondratenko N, Foster DM, Quehenberger O, Steinberg D. Surface expression and rapid internalization of macrosialin (mouse CD68) on elicited mouse peritoneal macrophages. J Leukoc Biol 2000;67:104-108.

David S, Kroner A. Repertoire of microglial and macrophage responses after spinal cord injury. Nat Rev Neurosci 2011;12:388-399.

Franquesa M, Hoogduijn MJ, Reinders ME, et al. Mesenchymal Stem Cells in Solid Organ Transplantation (MiSOT) Fourth Meeting: lessons learned from first clinical trials. Transplantation 2013;96:234-238.

Lambertsen KL, Clausen BH, Babcock AA, et al. Microglia protect neurons against ischemia by synthesis of tumor necrosis factor. J Neurosci 2009;29:1319-1330.

Sierra A, Encinas JM, Deudero JJP, et al. Microglia shape adult hippocampal neurogenesis through apoptosis-coupled phagocytosis. Cell Stem Cell 2010;7:483-495.

Denes A, Vidyasagar R, Feng J, et al. Proliferating resident microglia after focal cerebral ischaemia in mice. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2007;27:1941-1953.

Sica A, Mantovani A. Macrophage plasticity and polarization: in vivo veritas. J Clin Invest 2012;122:787-795.

Walker PA, Bedi SS, Shah SK, et al. Intravenous multipotent adult progenitor cell therapy after traumatic brain injury: modulation of the resident microglia population. J Neuroinflammation 2012;9:228

Giunti D, Parodi B, Usai C, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells shape microglia effector functions through the release of CX3CL1. Stem Cells 2012;30:2044-2053.

Kim Y-J, Park H-J, Lee G, et al. Neuroprotective effects of human mesenchymal stem cells on dopaminergic neurons through anti-inflammatory action. Glia 2009;57:13-23.

Micklem K, Rigney E, Cordell J, et al. A human macrophage-associated antigen (CD68) detected by six different monoclonal antibodies. Br J Haematol 1989;73:6-11.

Holness CL, Simmons DL. Molecular cloning of CD68, a human macrophage marker related to lysosomal glycoproteins. Blood 1993;81:1607-1613.

Travaglione S, Falzano L, Fabbri A, Stringaro A, Fais S, Fiorentini C. Epithelial cells and expression of the phagocytic marker CD68: scavenging of apoptotic bodies following Rho activation. Toxicol In Vitro 2002;16:405-411.

Neher JJ, Neniskyte U, Zhao J-W, Bal-Price A, Tolkovsky AM, Brown GC. Inhibition of microglial phagocytosis is sufficient to prevent inflammatory neuronal death. J Immunol 2011;186:4973-4983.

Neher JJ, Neniskyte U, Brown GC. Primary phagocytosis of neurons by inflamed microglia: potential roles in neurodegeneration. Front Pharmacol 2012;3:27.

Bonilla C, Zurita M, Otero L, Aguayo C, Vaquero J. Delayed intralesional transplantation of bone marrow stromal cells increases endogenous neurogenesis and promotes functional recovery after severe traumatic brain injury. Brain Inj 2009;23:760-769

Mahmood A, Lu D, Qu C, Goussev A, Chopp M. Treatment of traumatic brain injury with a combination therapy of marrow stromal cells and atorvastatin in rats. Neurosurgery 2007;60:546-553.

Qu C, Mahmood A, Lu D, Goussev A, Xiong Y, Chopp M. Treatment of traumatic brain injury in mice with marrow stromal cells. Brain Res 2008;1208:234-239.

Sato A, Ohtaki H, Tsumuraya T, et al. Interleukin-1 participates in the classical and alternative activation of microglia/macrophages after spinal cord injury. J Neuroinflammation 2012;9:65.

Babcock AA, Kuziel WA, Rivest S, Owens T. Chemokine expression by glial cells directs leukocytes to sites of axonal injury in the CNS. J Neurosci 2003;23:7922-7930.

Si Y, Tsou C-L, Croft K, Charo IF. CCR2 mediates hematopoietic stem and progenitor cell trafficking to sites of inflammation in mice. J Clin Invest 2010;120:1192-1203.

Biswas SK, Mantovani A. Macrophage plasticity and interaction with lymphocyte subsets: cancer as a paradigm. Nat Immunol 2010;11:889-896.

Butovsky O, Bukshpan S, Kunis G, Jung S, Schwartz M. Microglia can be induced by IFN-gamma or IL-4 to express neural or dendritic-like markers. Mol Cell Neurosci 2007;35:490-500.

Cho HH, Kim YJ, Kim JT, et al. The role of chemokines in proangiogenic action induced by human adipose tissue-derived mesenchymal stem cells in the murine model of hindlimb ischemia. Cell Physiol Biochem 2009;24:511-518.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Progetto ricerca finalizzata FR-CCM-2008-1248388 and FISM2012/R/17 to C.V. We thank Professor Maria Pia Abbracchio and Dr. Davide Lecca, 20133 University of Milan, for useful discussions; and Ilaria Prada (IN CNR, Milan) for assistance with some of the experiments. We also thank the association “Esserci con Cate per i Bimbi”, which supported this work.

Required Author Forms

Disclosure forms provided by the authors are available with the online version of this article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Zanier, E.R., Pischiutta, F., Riganti, L. et al. Bone Marrow Mesenchymal Stromal Cells Drive Protective M2 Microglia Polarization After Brain Trauma. Neurotherapeutics 11, 679–695 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13311-014-0277-y

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13311-014-0277-y