Abstract

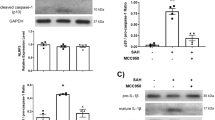

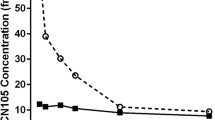

Subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) is a neurologically destructive stroke in which early brain injury (EBI) plays a pivotal role in poor patient outcomes. Expanding upon our previous work, multiple techniques and methods were used in this preclinical study to further elucidate the mechanisms underlying the beneficial effects of apolipoprotein E (ApoE) against EBI after SAH in murine apolipoprotein E gene-knockout mice (Apoe−/−, KO) and wild-type mice (WT) on a C57BL/6J background. We reported that Apoe deficiency resulted in a more extensive EBI at 48 h after SAH in mice demonstrated by MRI scanning and immunohistochemical staining and exhibited more extensive white matter injury and neuronal apoptosis than WT mice. These changes were associated with an increase in NADPH oxidase 2 (NOX2) expression, an important regulator of both oxidative stress and inflammatory cytokines. Furthermore, immunohistochemical analysis revealed that NOX2 was abundantly expressed in activated M1 microglia. The JAK2/STAT3 signaling pathway, an upstream regulator of NOX2, was increased in WT mice and activated to an even greater extent in Apoe−/− mice; whereas, the JAK2-specific inhibitor, AG490, reduced NOX2 expression, oxidative stress, and inflammation in Apoe-deficient mice. Also, apoE-mimetic peptide COG1410 suppressed the JAK2/STAT3 signaling pathway and significantly reduced M1 microglia activation with subsequent attenuation of oxidative stress and inflammation after SAH. Taken together, apoE and apoE-mimetic peptide have whole-brain protective effects that may reduce EBI after SAH via M1 microglial quiescence through the attenuation of the JAK2/STAT3/NOX2 signaling pathway axis.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Suzuki H, Shiba M, Nakatsuka Y, Nakano F, Nishikawa H. Higher cerebrospinal fluid pH may contribute to the development of delayed cerebral ischemia after aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. Transl Stroke Res. 2017;8(2):165–73. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12975-016-0500-8.

Etminan N. Aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage—status quo and perspective. Transl Stroke Res. 2015;6(3):167–70. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12975-015-0398-6.

Sabri M, Lass E, Macdonald RL. Early brain injury: a common mechanism in subarachnoid hemorrhage and global cerebral ischemia. Stroke Res Treat. 2013;2013:394036–9. https://doi.org/10.1155/2013/394036.

Fan LF, He PY, Peng YC, Du QH, Ma YJ, Jin JX, et al. Mdivi-1 ameliorates early brain injury after subarachnoid hemorrhage via the suppression of inflammation-related blood-brain barrier disruption and endoplasmic reticulum stress-based apoptosis. Free Radic Biol Med. 2017;112:336–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2017.08.003.

Cai J, Cao S, Chen J, Yan F, Chen G, Dai Y. Progesterone alleviates acute brain injury via reducing apoptosis and oxidative stress in a rat experimental subarachnoid hemorrhage model. Neurosci Lett. 2015;600:238–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neulet.2015.06.023.

Atangana E, Schneider UC, Blecharz K, Magrini S, Wagner J, Nieminen-Kelha M, et al. Intravascular inflammation triggers intracerebral activated microglia and contributes to secondary brain injury after experimental subarachnoid hemorrhage (eSAH). Transl Stroke Res. 2017;8(2):144–56. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12975-016-0485-3.

Hasegawa Y, Suzuki H, Uekawa K, Kawano T, Kim-Mitsuyama S. Characteristics of cerebrovascular injury in the hyperacute phase after induced severe subarachnoid hemorrhage. Transl Stroke Res. 2015;6(6):458–66. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12975-015-0423-9.

Egashira Y, Hua Y, Keep RF, Xi G. Acute white matter injury after experimental subarachnoid hemorrhage: potential role of lipocalin 2. Stroke. 2014;45(7):2141–3. https://doi.org/10.1161/STROKEAHA.114.005307.

Guo D, Wilkinson DA, Thompson BG, Pandey AS, Keep RF, Xi G, et al. MRI characterization in the acute phase of experimental subarachnoid hemorrhage. Transl Stroke Res. 2017;8(3):234–43. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12975-016-0511-5.

Cheng C, Jiang L, Yang Y, Wu H, Huang Z, Sun X. Effect of APOE gene polymorphism on early cerebral perfusion after aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. Transl Stroke Res. 2015;6(6):446–50. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12975-015-0426-6.

Lawrence DW, Comper P, Hutchison MG, Sharma B. The role of apolipoprotein E episilon (epsilon)-4 allele on outcome following traumatic brain injury: a systematic review. Brain Inj. 2015;29(9):1018–31. https://doi.org/10.3109/02699052.2015.1005131.

Handattu SP, Monroe CE, Nayyar G, Palgunachari MN, Kadish I, van Groen T, et al. In vivo and in vitro effects of an apolipoprotein e mimetic peptide on amyloid-beta pathology. J Alzheimers Dis. 2013;36(2):335–47. https://doi.org/10.3233/JAD-122377.

Wei J, Zheng M, Liang P, Wei Y, Yin X, Tang Y, et al. Apolipoprotein E and its mimetic peptide suppress Th1 and Th17 responses in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Neurobiol Dis. 2013;56:59–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nbd.2013.04.009.

Laskowitz DT, Vitek MP. Apolipoprotein E and neurological disease: therapeutic potential and pharmacogenomic interactions. Pharmacogenomics. 2007;8(8):959–69. https://doi.org/10.2217/14622416.8.8.959.

Pang J, Wu Y, Peng J, Yang P, Kuai L, Qin X, et al. Potential implications of apolipoprotein E in early brain injury after experimental subarachnoid hemorrhage: involvement in the modulation of blood-brain barrier integrity. Oncotarget. 2016;7(35):56030–44. https://doi.org/10.18632/oncotarget.10821.

Peng JH, Qin XH, Pang JW, Wu Y, Dong JH, Huang CR, et al. Apolipoprotein E epsilon4: a possible risk factor of intracranial pressure and white matter perfusion in good-grade aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage patients at early stage. Front Neurol. 2017;8:150. https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2017.00150.

Pang J, Chen Y, Kuai L, Yang P, Peng J, Wu Y, et al. Inhibition of blood-brain barrier disruption by an apolipoprotein E-mimetic peptide ameliorates early brain injury in experimental subarachnoid hemorrhage. Transl Stroke Res. 2017;8(3):257–72. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12975-016-0507-1.

Gao J, Wang H, Sheng H, Lynch JR, Warner DS, Durham L, et al. A novel apoE-derived therapeutic reduces vasospasm and improves outcome in a murine model of subarachnoid hemorrhage. Neurocrit Care. 2006;4(1):25–31. https://doi.org/10.1385/NCC:4:1:025.

Wang H, Anderson LG, Lascola CD, James ML, Venkatraman TN, Bennett ER, et al. ApolipoproteinE mimetic peptides improve outcome after focal ischemia. Exp Neurol. 2013;241:67–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.expneurol.2012.11.027.

Qin X, You H, Cao F, Wu Y, Peng J, Pang J, et al. Apolipoprotein E mimetic peptide increases cerebral glucose uptake by reducing blood-brain barrier disruption after controlled cortical impact in mice: an (18)F-fluorodeoxyglucose PET/CT study. J Neurotrauma. 2017;34(4):943–51. https://doi.org/10.1089/neu.2016.4485.

Cao F, Jiang Y, Wu Y, Zhong J, Liu J, Qin X, et al. Apolipoprotein E-mimetic COG1410 reduces acute vasogenic edema following traumatic brain injury. J Neurotrauma. 2016;33(2):175–82. https://doi.org/10.1089/neu.2015.3887.

Laskowitz DT, Lei B, Dawson HN, Wang H, Bellows ST, Christensen DJ, et al. The apoE-mimetic peptide, COG1410, improves functional recovery in a murine model of intracerebral hemorrhage. Neurocrit Care. 2012;16(2):316–26. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12028-011-9641-5.

Charan J, Kantharia ND. How to calculate sample size in animal studies? J Pharmacol Pharmacother. 2013;4(4):303–6. https://doi.org/10.4103/0976-500X.119726.

Muroi C, Fujioka M, Marbacher S, Fandino J, Keller E, Iwasaki K, et al. Mouse model of subarachnoid hemorrhage: technical note on the filament perforation model. Acta Neurochir Suppl. 2015;120:315–20. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-04981-6_54.

Damm J, Harden LM, Gerstberger R, Roth J, Rummel C. The putative JAK-STAT inhibitor AG490 exacerbates LPS-fever, reduces sickness behavior, and alters the expression of pro- and anti-inflammatory genes in the rat brain. Neuropharmacology. 2013;71:98–111. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuropharm.2013.03.014.

Sugawara T, Ayer R, Jadhav V, Zhang JH. A new grading system evaluating bleeding scale in filament perforation subarachnoid hemorrhage rat model. J Neurosci Methods. 2008;167(2):327–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jneumeth.2007.08.004.

Chen Q, Shi X, Tan Q, Feng Z, Wang Y, Yuan Q, et al. Simvastatin promotes hematoma absorption and reduces hydrocephalus following intraventricular hemorrhage in part by upregulating CD36. Transl Stroke Res. 2017;8(4):362–73. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12975-017-0521-y.

Jiang B, Li L, Chen Q, Tao Y, Yang L, Zhang B, et al. Role of glibenclamide in brain injury after intracerebral hemorrhage. Transl Stroke Res. 2017;8(2):183–93. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12975-016-0506-2.

Liu H, Zhao L, Yue L, Wang B, Li X, Guo H, et al. Pterostilbene attenuates early brain injury following subarachnoid hemorrhage via inhibition of the NLRP3 inflammasome and Nox2-related oxidative stress. Mol Neurobiol. 2017;54(8):5928–40. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12035-016-0108-8.

Ransohoff RM. A polarizing question: do M1 and M2 microglia exist? Nat Neurosci. 2016;19(8):987–91. https://doi.org/10.1038/nn.4338.

Zhao H, Garton T, Keep RF, Hua Y, Xi G. Microglia/macrophage polarization after experimental intracerebral hemorrhage. Transl Stroke Res. 2015;6(6):407–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12975-015-0428-4.

Wang G, Zhang J, Hu X, Zhang L, Mao L, Jiang X, et al. Microglia/macrophage polarization dynamics in white matter after traumatic brain injury. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2013;33(12):1864–74. https://doi.org/10.1038/jcbfm.2013.146.

Wang J, Ma MW, Dhandapani KM, Brann DW. Regulatory role of NADPH oxidase 2 in the polarization dynamics and neurotoxicity of microglia/macrophages after traumatic brain injury. Free Radic Biol Med. 2017;113:119–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2017.09.017.

Bahar E, Kim JY, Yoon H. Quercetin attenuates manganese-induced neuroinflammation by alleviating oxidative stress through regulation of apoptosis, iNOS/NF-kappaB and HO-1/Nrf2 pathways. Int J Mol Sci. 2017;18(9). https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms18091989.

Ito F, Yamada Y, Shigemitsu A, Akinishi M, Kaniwa H, Miyake R, et al. Role of oxidative stress in epigenetic modification in endometriosis. Reprod Sci. 2017;24(11):1493–502. https://doi.org/10.1177/1933719117704909.

Justicia C, Salas-Perdomo A, Perez-de-Puig I, Deddens LH, van Tilborg GAF, Castellvi C, et al. Uric acid is protective after cerebral ischemia/reperfusion in hyperglycemic mice. Transl Stroke Res. 2017;8(3):294–305. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12975-016-0515-1.

Sundboll J, Horvath-Puho E, Schmidt M, Dekkers OM, Christiansen CF, Pedersen L, et al. Preadmission use of glucocorticoids and 30-day mortality after stroke. Stroke. 2016;47(3):829–35. https://doi.org/10.1161/STROKEAHA.115.012231.

Patel MM, Patel BM. Crossing the blood-brain barrier: recent advances in drug delivery to the brain. CNS Drugs. 2017;31(2):109–33. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40263-016-0405-9.

Dose J, Huebbe P, Nebel A, Rimbach G. APOE genotype and stress response—a mini review. Lipids Health Dis. 2016;15:121. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12944-016-0288-2.

Cai X, Li X, Li L, Huang XZ, Liu YS, Chen L, et al. Adiponectin reduces carotid atherosclerotic plaque formation in ApoE−/− mice: roles of oxidative and nitrosative stress and inducible nitric oxide synthase. Mol Med Rep. 2015;11(3):1715–21. https://doi.org/10.3892/mmr.2014.2947.

Ferguson S, Mouzon B, Kayihan G, Wood M, Poon F, Doore S, et al. Apolipoprotein E genotype and oxidative stress response to traumatic brain injury. Neuroscience. 2010;168(3):811–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroscience.2010.01.031.

Lomnitski L, Chapman S, Hochman A, Kohen R, Shohami E, Chen Y, et al. Antioxidant mechanisms in apolipoprotein E deficient mice prior to and following closed head injury. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1999;1453(3):359–68.

Fan LM, Cahill-Smith S, Geng L, Du J, Brooks G, Li JM. Aging-associated metabolic disorder induces Nox2 activation and oxidative damage of endothelial function. Free Radic Biol Med. 2017;108:940–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2017.05.008.

Cooney SJ, Bermudez-Sabogal SL, Byrnes KR. Cellular and temporal expression of NADPH oxidase (NOX) isotypes after brain injury. J Neuroinflammation. 2013;10:155. https://doi.org/10.1186/1742-2094-10-155.

Chen J, Cui C, Yang X, Xu J, Venkat P, Zacharek A, et al. MiR-126 affects brain-heart interaction after cerebral ischemic stroke. Transl Stroke Res. 2017;8(4):374–85. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12975-017-0520-z.

Zhang L, Li Z, Feng D, Shen H, Tian X, Li H, et al. Involvement of Nox2 and Nox4 NADPH oxidases in early brain injury after subarachnoid hemorrhage. Free Radic Res. 2017;51(3):316–28. https://doi.org/10.1080/10715762.2017.1311015.

Quesada IM, Lucero A, Amaya C, Meijles DN, Cifuentes ME, Pagano PJ, et al. Selective inactivation of NADPH oxidase 2 causes regression of vascularization and the size and stability of atherosclerotic plaques. Atherosclerosis. 2015;242(2):469–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2015.08.011.

Corzo CA, Cotter MJ, Cheng P, Cheng F, Kusmartsev S, Sotomayor E, et al. Mechanism regulating reactive oxygen species in tumor-induced myeloid-derived suppressor cells. J Immunol. 2009;182(9):5693–701. https://doi.org/10.4049/jimmunol.0900092.

Hung CC, Lin CH, Chang H, Wang CY, Lin SH, Hsu PC, et al. Astrocytic GAP43 induced by the TLR4/NF-kappaB/STAT3 axis attenuates astrogliosis-mediated microglial activation and neurotoxicity. J Neurosci. 2016;36(6):2027–43. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3457-15.2016.

Ben Haim L, Ceyzeriat K, Carrillo-de Sauvage MA, Aubry F, Auregan G, Guillermier M, et al. The JAK/STAT3 pathway is a common inducer of astrocyte reactivity in Alzheimer’s and Huntington’s diseases. J Neurosci. 2015;35(6):2817–29. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3516-14.2015.

Qin C, Fan WH, Liu Q, Shang K, Murugan M, Wu LJ, et al. Fingolimod protects against ischemic white matter damage by modulating microglia toward M2 polarization via STAT3 pathway. Stroke. 2017;48(12):3336–46. https://doi.org/10.1161/STROKEAHA.117.018505.

An JY, Pang HG, Huang TQ, Song JN, Li DD, Zhao YL, et al. AG490 ameliorates early brain injury via inhibition of JAK2/STAT3-mediated regulation of HMGB1 in subarachnoid hemorrhage. Exp Ther Med. 2018;15(2):1330–8. https://doi.org/10.3892/etm.2017.5539.

Yang L, Liu CC, Zheng H, Kanekiyo T, Atagi Y, Jia L, et al. LRP1 modulates the microglial immune response via regulation of JNK and NF-kappaB signaling pathways. J Neuroinflammation. 2016;13(1):304. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12974-016-0772-7.

Buunk AM, Groen RJM, Veenstra WS, Metzemaekers JDM, van der Hoeven JH, van Dijk JMC, et al. Cognitive deficits after aneurysmal and angiographically negative subarachnoid hemorrhage: memory, attention, executive functioning, and emotion recognition. Neuropsychology. 2016;30(8):961–9. https://doi.org/10.1037/neu0000296.

Acknowledgments

We thank radiologist Yu Guo and his team for the help of MRI scanning and data analysis. We also thank Cognosci Inc. for the kindness of providing ApoE mimetic peptide COG1410 and Prof. David Brody for the help with improving the quality of our manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81771278, 81801176), Sichuan Provincial Health and Family Planning Commission research project (17PJ076), Technology Innovation Talent Project of Sichuan Province (2018RZ0090)), Luzhou Government-Southwest Medical University Strategic Cooperation Project (2016LZXNYD-J12, 2016LZXNYD-Z02), and the Youth Innovation Project of Sichuan Medical Scientific Research (Q17082).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

All experimental procedures were approved by the Ethics Committee of Southwest Medical University and carried out in accordance with Stroke Treatment and Academic Roundtable (STAIR) guidelines and the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Pang, J., Peng, J., Matei, N. et al. Apolipoprotein E Exerts a Whole-Brain Protective Property by Promoting M1? Microglia Quiescence After Experimental Subarachnoid Hemorrhage in Mice. Transl. Stroke Res. 9, 654–668 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12975-018-0665-4

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12975-018-0665-4