Abstract

Creationism with respect to fictional entities, i.e., the position according to which ficta are creations of human practices, has recently become the most popular realist account of fictional entities. For it allows one to hold that there are fictional entities while simultaneously giving such entities a respectable metaphysical status, that of abstract artifacts. In this paper, I will draw what are the ontological and semantical consequences of this position, or at least of all its forms that are genuinely creationist. For some people, these consequences will sound as plagues against the position; for some others, especially realists on ficta, they are welcome results. Although I hold that all forms of genuine creationism have these consequences, I will conclude by explaining why I take moderate creationism, according to which ficta are created by means of a reflexive stance on the make-believe practice grounding them, to be the best of these forms.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

I put “human” into brackets for some people believe that the kind of activity that lurks behind ficta’s creation, namely a make-believe activity, can be also shared by animals. For the purposes of this paper, I do not want to deal with this problem, whose solution partly depends on how one interprets what a make-believe activity consists in.

For the importance of this point, cf. Thomasson (1999:56).

In point of fact, a more refined explanation should be needed to explain why qua abstract creations ficta are also taken to be artifacts, i.e., intentional constructions. For something on it, cf. Voltolini (2006).

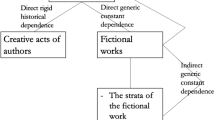

This idea, originally suggested by Ingarden (1931), has been recently revived by Thomasson (1999), who specifies that this dependence is rigid (a fictum depends for its existence on the existence of a particular thought of its creator) as well as historical (the fictum comes into existence only once that thought occurs). It has nowadays many (explicit and implicit) followers; cf. e.g., Predelli (1997).

Some say that making believe that p is a sui generis mental state; cf. e.g., Currie (1990). Yet there are reasons not to conceive a make-believe practice as consisting in the practitioners’ having mental states of a certain kind. For Walton (1990), for instance, a make-believe practice is the normative activity of prescribing someone to imagine that p, q, r… is the case. Moreover, the mind-dependence involved in this kind of creationism is probably just a generic dependence: a dependence on some thought or other.

For this idea, cf. Voltolini (2006).

As Thomasson puts it, a fictional character also depends for its existence constantly and generically on (copies of) fictional works. Cf. (1999:7, 36).

By presupposing of course that there may something like a shared intentional object, an idea which notoriously raises serious problems since Geach (1972). But insofar as in Thomasson’s perspective a fictional object has at least to be a shared intentional object, quasicreationism has obviously to endorse that presupposition.

Cf. Thomasson (1999:89).

This problem is very vivid for Thomasson, who holds a metaphysical picture according to which there are different kinds of intentional objects: cf. (1999:90). Yet the problem is completely independent of the metaphysical conception of intentional objects one endorses. Suppose that one endorsed a metaphysically deflationary conception of intentionalia such as that defended by Crane (2001), according to which qua targets of one’s thought, intentionalia are schematic objects, in the sense that they have as such no particular nature: that is, being an intentional object is not a genuine metaphysical category, any intentional object has rather the nature of the object it is actually identical with (a number, a nation, a concretum…). Even in that perspective, every intentionale has the actual nature it forever has, so if it is a fictional entity it is such from the very beginning, it does not turn into such an entity.

Cf. Thomasson (1999:11–2, 36).

Cf. Thomasson (1999: 90).

For this account of ficta’s creation, cf. Priest (2005:120).

To put it in more technical terms (following Predelli (1997, 2005); but the point is implicit also in Thomasson (1999)), for a quasicreationist fictional contexts, i.e., contexts in which sentences containing singular terms like “Desdemona”, “Othello”, and “Holmes” are used in a make-believe practice, obviously contain points of truth-evaluation, but do not constitute alternative contexts of interpretation for such sentences so used. That is, those sentences do not receive a semantical interpretation which differs from the one they have when used outside such contexts; no context-shift is involved. Whereas every genuine creationist (explicitly or implicitly) maintains precisely the opposite: see later in the text.

I here basically follow Recanati’s (2000) account.

That a world may figure also as a parameter for the determination of what a certain sentence contextually says is a well-known story. Cf. e.g., Predelli (2005). If people living in a possible world different from the real one said “Actually, Italy is polluted”, they would say something different from what we in the real world would say if we uttered another token of that sentence: they would say that Italy is polluted in their own world. Following Recanati (2000), the idea is simply that of extending to worlds of make-believe, that are not possible worlds in the technical sense of modal logic (they are neither consistent nor complete), the role of contextual parameters. As a matter of fact, the above sentence could even be uttered by the protagonists of a story concerning Italy, so that that sentence would say that Italy is polluted in the make-believe world of that story.

Cf. Adams (1981:22) for the notion of being true-in-a-world and its difference from the notion of being-true-at-a-world, which corresponds to the idea of the truthvalue a sentence has when evaluated of a world which differs from the world that figures as the ‘world’-parameter of the context yielding that sentence a semantical interpretation.

Again with Evans (1982).

We will see later, namely, à propos of the sixth consequence, why this specification is needed.

The storyteller and her audience are affected by what Evans (1982) would call existentially conservative make-believe practices, that is, practices in which of an already constituted individual, one makes believe that that individual does certain things. Conan Doyle’s storytelling, for instance, is an existentially conservative practice with respect to London. On these practices and their difference from the more usual existentially creative make-believe practices such as those affecting Othello and Santa, see later in the text.

For such kind of mistakes, cf. Salmon (2002).

A similar idea has been apparently defended originally by Meinong. Cf. on this Kroon (1992:518–9).

Walton (1997) himself has implicitly acknowledged this. In order for this supervenience to really obtain, however, storylisteners must be able of intending objects which are actually identical with those real characters, regardless of whether storylisteners are aware of that identity. This presupposes a conception of intentional objects as schematic entities à la Crane (2001). On this, cf. Voltolini (2008).

Cf. Yablo (1999).

For emotions towards merely possible entities, see also Szabó-Gendler and Kovakovich (2005:249).

In order to avoid this sixth consequence, what a creationist should rather try to argue for is that in such cases no hypostatizing use follows the existentially conservative make-believe practice. As a matter of fact, the reason why a creationist may be reluctant in accepting this consequence is that it also forces her to maintain that when an existentially conservative make-believe practice concerns a real concrete individual and a hypostatizing use follows that practice, that use does not regard that real concrete individual, but it rather concerns a real abstract fictional character somehow corresponding to that concrete individual (say, the London of the Doyle’s stories, the Napoleon of War and Peace, and so on). Yet for some creationists this may well be a welcome result. Cf. Voltolini (2006:chap. 4).

I owe this suggestion to Amie Thomasson.

Incidentally, this is not a problem for the quasicreationist, for whom the relevant entity has been originally generated when the storyteller first conceives of the story’s character. But I have already ruled quasicreationism out of consideration for the different problems I raised at the beginning of this paper.

How can the moderate creationist account for those jumps? Well, perhaps by saying that they are merely apparent provisional exits from the pretence. In ruminating, the storyteller is still involved in the pretence, by qualifying the tale’s protagonists not as concrete entities, as she typically does all along, but as fictional characters. Sometimes this happens explicitly, when the storyteller ‘intrudes’ in the story by declaring the fictional nature of the pseudoindividual she makes believe that it exists. On these ‘intrusions’ see Pelletier (2003).

Yagisawa (2001) raises a different criticism to the same effect.

Salmon (2002) similarly attempts to reject the idea that there are imaginary entities of a similar abstract kind. According to Caplan (2004), there is no way to reject these latter entities once one accepts fictional and mythological entities as abstracta of the same kind. Here I try to give a reason as to why Salmon is right in his attempt.

Cf. Walton (1990:43–50).

Previous versions of this paper have been presented in seminars at the University of Turin, Italy, Victoria University, Wellington New Zealand, and Geneva University, Switzerland. I thank all the participants to those seminars for their stimulating remarks. Many thanks to Carola Barbero, Fred Kroon, Kevin Mulligan, and Amie Thomasson for their important comments.

References

Adams R (1981) Actualism and thisness. Synthese 49: 3–41

Caplan B (2004) Creatures of fiction, myth, and imagination. American Philosophical Quarterly 41: 331–337

Crane T (2001) Elements of mind. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Currie G (1990) The nature of fiction. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Evans G (1982) The varieties of reference. Clarendon, Oxford

Everett A (2005) Against fictional realism. The Journal of Philosophy 102: 624–649

Everett A (2007) Pretence, existence, and fictional objects. Philosophy and Phenomenological Research 74: 56–80

Geach P (1972) Intentional identity. In: Geach P. Logic Matters, Blackwell, Oxford: 146–153

Ingarden R (1931) Das literarische Kunstwerk. Niemeyer, Tübingen; transl. by G.G. Grabowicz, Northwestern University Press, Evanston 1973

Kroon F (1992) Was Meinong only pretending? Philosophy and Phenomenological Research 52: 499–527

Kroon F (2004) Descriptivism, pretence, and the Frege–Russell problem. The Philosophical Review 113: 1–30

Kroon F (2005) Beliefs about nothing in particular. In: Calderon M.E (ed) Fictionalism in metaphysics. Oxford University Press, New York: 178–203

Lamarque P (1981) How can we fear and pity fictions? British Journal of Aesthetics 21: 291–304

Lewis D (1978) Truth in fiction. American Philosophical Quarterly 15: 37–46

Pelletier J (2003) ‘Vergil and Dido’. Dialectica 57: 191–203

Predelli S (1997) Talk about fiction. Erkenntnis 46: 69–77

Predelli S (2002) ‘Holmes’ and Holmes. A Millian analysis of names from fiction. Dialectica 56: 261–279

Predelli S (2005) Contexts. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Priest G (2005) Towards non-being: the logic and metaphysics of intentionality. Clarendon, Oxford

Recanati F (2000) Oratio obliqua, oratio recta. MIT Press, Cambridge

Rorty R (1982) Is there a problem about fictional discourse? In: Rorty R. Consequences of pragmatism, Harvester, Brighton: 110–138

Salmon N (1998) Nonexistence. Noûs 32: 277–319

Salmon N (2002) Mythical objects. In: Campbell J.K et al (eds) Meaning and truth: investigations in philosophical semantics. Seven Bridges, New York: 105–123

Schiffer S (1996) Language-created language-independent entities. Philosophical Topics 24: 149–166

Schiffer S (2003) The things we mean. Clarendon, Oxford

Searle J.R (1979) The logical status of fictional discourse. In: French P.A et al (eds) Contemporary perspectives in the philosophy of language. University of Minneapolis Press, Minneapolis: 233–243

Smith B (1984) How not to talk about what does not exist. In: Haller R (ed) Aesthetics. Hölder-Pichler-Tempsky, Vienna: 196–198

Szabó-Gendler T, Kovakovich K (2005) Genuine rational fictional emotions. In: Kieran M (ed) Contemporary debates in aesthetics and the philosophy of art. Blackwell, Oxford: 241–253

Thomasson A.L (1999) Fiction and metaphysics. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Thomasson A.L (2003a) Fictional characters and literary practices. British Journal of Aesthetics 43: 138–157

Thomasson A.L (2003b) Speaking of fictional characters. Dialectica 57: 205–223

Yablo S (1999) The strange thing about the figure in the bathhouse. Review of Thomasson, A. L (1999). Times Literary Supplement, November 5

Walton K.L (1978) Fearing fictions. The Journal of Philosophy 75: 5–25

Walton K.L (1990) Mimesis as make-believe. Harvard University Press, Cambridge

Walton K.L (1997) Spelunking, simulation, and slime. In: Hjort M, Laver S (eds) Emotion and the arts. Oxford University Press, Oxford: 37–49

Yagisawa T (2001) Against creationism in fiction. Philosophical Perspectives 15: 153–172

Voltolini A (2006) How ficta follow fiction. Springer, Dordrecht

Voltolini A (2008) Consequences of schematism. Phenomenology and the Cognitive Sciences. doi:10.1007/s11097-008-9108-0

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

About this article

Cite this article

Voltolini, A. The Seven Consequences of Creationism. Int Ontology Metaphysics 10, 27–48 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12133-008-0038-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12133-008-0038-7