Abstract

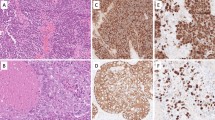

This review article provides a brief overview of the new WHO classification by adopting a question–answer model to highlight the spectrum of head and neck neuroendocrine neoplasms which includes epithelial neuroendocrine neoplasms (neuroendocrine tumors and neuroendocrine carcinomas) arising from upper aerodigestive tract and salivary glands, and special neuroendocrine neoplasms including middle ear neuroendocrine tumors (MeNET), ectopic or invasive pituitary neuroendocrine tumors (PitNET; formerly known as pituitary adenoma) and Merkel cell carcinoma as well as non-epithelial neuroendocrine neoplasms (paragangliomas). The new WHO classification follows the IARC/WHO nomenclature framework and restricts the diagnostic term of neuroendocrine carcinoma to poorly differentiated epithelial neuroendocrine neoplasms. In this classification, well-differentiated epithelial neuroendocrine neoplasms are termed as neuroendocrine tumors (NET), and are graded as G1 NET (no necrosis and < 2 mitoses per 2 mm2; Ki67 < 20%), G2 NET (necrosis or 2–10 mitoses per 2 mm2, and Ki67 < 20%) and G3 NET (> 10 mitoses per 2 mm2 or Ki67 > 20%, and absence of poorly differentiated cytomorphology). Neuroendocrine carcinomas (> 10 mitoses per 2 mm2, Ki67 > 20%, and often associated with a Ki67 > 55%) are further subtyped based on cytomorphological characteristics as small cell and large cell neuroendocrine carcinomas. Unlike neuroendocrine carcinomas, head and neck NETs typically show no aberrant p53 expression or loss of RB reactivity. Ectopic or invasive PitNETs are subtyped using pituitary transcription factors (PIT1, TPIT, SF1, GATA3, ER-alpha), hormones and keratins (e.g., CAM5.2). The new classification emphasizes a strict correlation of morphology and immunohistochemical findings in the accurate diagnosis of neuroendocrine neoplasms. A particular emphasis on the role of biomarkers in the confirmation of the neuroendocrine nature of a neoplasm and in the distinction of various neuroendocrine neoplasms is provided by reviewing ancillary tools that are available to pathologists in the diagnostic workup of head and neck neuroendocrine neoplasms. Furthermore, the role of molecular immunohistochemistry in the diagnostic workup of head and neck paragangliomas is discussed. The unmet needs in the field of head and neck neuroendocrine neoplasms are also discussed in this article. The new WHO classification is an important step forward to ensure accurate diagnosis that will also form the basis of ongoing research in this field.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Rosai J. The origin of neuroendocrine tumors and the neural crest saga. Mod Pathol. 2011;24:S53–7.

Pearse AG. The cytochemistry and ultrastructure of polypeptide hormone-producing cells of the APUD series and the embryologic, physiologic and pathologic implications of the concept. J Histochem Cytochem. 1969;17:303–13.

Fontaine J, Le Douarin NM. Analysis of endoderm formation in the avian blastoderm by use of quail-chick chimeras. The problem of the neuroectodermal origin of the cells of the APUD series. J Embryol Exp Morphol. 1977;41:209–22.

Oberndorfer S. Karzinoide Tumoren des Dünndarms. Frankf Z Pathol. 1907;1:426–32.

Gosset A, Masson P. Tumeurs endocrines de lappendice. Presse Med. 1914;25:237–40.

Williams ED, Sandler M. The classification of carcinoid tumours. Lancet. 1963;281:238–9.

Gould VE, Memoli VA, Dardi LE. Multidirectional differentiation in human epithelial cancers. J Submicrosc Cytol. 1981;13:97–115.

Liebow A. Tumors of the lower respiratory tract. Washington, DC: Armed Forces Institute of Pathology; 1952.

Bensch KG, Corrin B, Pariente R, Spencer H. Oat-cell carcinoma of the lung: its origin and relationship to bronchial carcinoid. Cancer. 1968;22:1163–72.

Goodner JT, Berg JW, Watson WL. The nonbenign nature of bronchial carcinoids and cylindromas. Cancer. 1961;14:539–46.

Arrigoni MG, Woolner LB, Bernatz PR. Atypical carcinoid of the lung. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1972;64:413–21.

Gould VE, Linnoila I, Memoli VA, Warren WH. Neuroendocrine cells and neuroendocrine neoplasms of the lung. Pathol Annu. 1983;18:287–330.

Wenig BM, Hyams VJ, Heffner DK. Moderately differentiated neuroendocrine carcinoma of the larynx: a clinicopathologic study of 54 cases. Cancer. 1988;62:2658–76.

Mills SE. Neuroectodermal neoplasms of the head and neck with special emphasis on neuroendocrine carcinomas. Mod Pathol. 2002;15:264–78.

Lewis JS Jr, Spence DC, Chiosea S, et al. Large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the larynx: definition of an entity. Head Neck Pathol. 2010;4:198–207.

Lewis JS Jr, Ferlito A, Gnepp DR, et al. Terminology and classification of neuroendocrine neoplasms of the larynx. Laryngoscope. 2011;121:11897–21193.

Perez-Ordonez B, et al. WHO classification of head & neck tumours. IARC: Lyon; 2017. p. 95–8.

Rindi G, Klimstra DS, Abedi-Ardekani B, et al. A common classification framework for neuroendocrine neoplasms: an International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) and World Health Organization (WHO) expert consensus proposal. Mod Pathol. 2018;31:1770–86.

Rindi G, Inzani F. Neuroendocrine neoplasm: update: toward universal nomenclature. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2020;27:R211–8.

Klimstra DS, Modlin IR, Adsay V, et al. Pathology reporting of neuroendocrine tumors: application of the Delphic consensus process to the development of a minimum pathology data set. Am J Surg Pathol. 2010;34:300–13.

WHO Classification of Tumours Editorial Board. Head and neck tumours. Lyon (France): International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2022. (WHO classification of tumours series, 5th ed.; vol. 9). https://publications.iarc.fr/

Agaimy A, Jain D, Uddin N, Rooper LM, Bishop JA. SMARCA4-deficient sinonasal carcinoma: a series of 10 cases expanding the genetic spectrum of SWI/SNF-driven sinonasal malignancies. Am J Surg Pathol. 2020;44(5):703–10.

Duan K, Mete O. Algorithmic approach to neuroendocrine tumors in targeted biopsies: practical applications of immunohistochemical markers. Cancer Cytopathol. 2016;124:871–84.

Rooper LM, Bishop JA, Westra WH. INSM1 is a sensitive and specific marker of neuroendocrine differentiation in head and neck tumors. Am J Surg Pathol. 2018;42:665–71.

La Rosa S. Challenges in high-grade neuroendocrine neoplasms and mixed neuroendocrine/non-neuroendocrine neoplasms. Endocr Pathol. 2021;32:245–57.

Juhlin CC, Zedenius J, Höög A. Clinical routine application of the second-generation neuroendocrine markers ISL1, INSM1, and secretagogin in neuroendocrine neoplasia: staining outcomes and potential clues for determining tumor origin. Endocr Pathol. 2020;31:401–10.

Strojan P, Šifrer R, Ferlito A, Grašič-Kuhar C, Lanišnik B, Plavc G, Zidar N. Neuroendocrine carcinoma of the larynx and pharynx: a clinical and histopathological study. Cancers (Basel). 2021;13:4813.

Juhlin CC. Challenges in paragangliomas and pheochromocytomas: from histology to molecular immunohistochemistry. Endocr Pathol. 2021;32:228–44.

Hayashi T, Mete O. Head and neck paragangliomas: what does the pathologist need to know? Diagn Histopathol. 2014;20:316–25.

Mete O, Cintosun A, Pressman I, Asa SL. Epidemiology and biomarker profile of pituitary adenohypophysial tumors. Mod Pathol. 2018;31:900–9.

Mete O, Kefeli M, Çalışkan S, Asa SL. GATA3 immunoreactivity expands the transcription factor profile of pituitary neuroendocrine tumors. Mod Pathol. 2019;32:484–9.

Turchini J, Sioson L, Clarkson A, Sheen A, Gill AJ. Utility of GATA-3 expression in the analysis of pituitary neuroendocrine tumour (PitNET) transcription factors. Endocr Pathol. 2020;31:150–5.

Kimura N, Shiga K, Kaneko K, Sugisawa C, Katabami T, Naruse M. The diagnostic dilemma of GATA3 immunohistochemistry in pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma. Endocr Pathol. 2020;31:95–100.

Asa SL, Ezzat S, Mete O. The diagnosis and clinical significance of paragangliomas in unusual locations. J Clin Med. 2018;7:280.

Scott MP, Helm KF. Cytokeratin 20: a marker for diagnosing Merkel cell carcinoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 1999;21:16–20.

Miner AG, Patel RM, Wilson DA, Procop GW, Minca EC, Fullen DR, Harms PW, Billings SD. Cytokeratin 20-negative Merkel cell carcinoma is infrequently associated with the Merkel cell polyomavirus. Mod Pathol. 2015;28:498–504.

Mete O, Asa SL. Structure, function, and morphology in the classification of pituitary neuroendocrine tumors: the importance of routine analysis of pituitary transcription factors. Endocr Pathol. 2020;31:330–6.

Asa SL, Mete O. Immunohistochemical biomarkers in pituitary pathology. Endocr Pathol. 2018;29:130–6.

Yan M, Roncin KL, Wilhelm S, Wasman JK, Asa SL. Images in endocrine pathology: high-grade intrathyroidal parathyroid carcinoma with Crooke’s hyalinization. Endocr Pathol. 2020;31:190–4.

Bal M, Sharma A, Rane SU, et al. Neuroendocrine neoplasms of the larynx: a clinicopathologic analysis of 27 neuroendocrine tumors and neuroendocrine carcinomas. Head Neck Pathol. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12105-021-01367-9.

Kao HL, Chang WC, Li WY, Chia-Heng Li A, Fen-Yau LA. Head and neck large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma should be separated from atypical carcinoid on the basis of different clinical features, overall survival, and pathogenesis. Am J Surg Pathol. 2012;36:185–92.

Dogukan FM, Yilmaz Ozguven B, Dogukan R, Kabukcuoglu F. Comparison of monitor-image and printout-image methods in Ki-67 scoring of gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. Endocr Pathol. 2019;30:17–23.

Alos L, Hakim S, Larque AB, et al. p16 overexpression in high-grade neuroendocrine carcinomas of the head and neck: potential diagnostic pitfall with HPV-related carcinomas. Virchows Arch. 2016;469:277–84.

Halmos GB, van der Laan TP, van Hemel BM, et al. human papillomavirus involved in laryngeal neuroendocrine carcinoma? Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2013;270:719–25.

Uccella S, La Rosa S, Volante M, Papotti M. Immunohistochemical biomarkers of gastrointestinal, pancreatic, pulmonary, and thymic neuroendocrine neoplasms. Endocr Pathol. 2018;29:150–68.

Uccella S, La Rosa S, Metovic J, et al. Genomics of high-grade neuroendocrine neoplasms: well-differentiated neuroendocrine tumor with high-grade features (G3 NET) and neuroendocrine carcinomas (NEC) of various anatomic sites. Endocr Pathol. 2021;32(1):192–210.

Liverani C, Bongiovanni A, Mercatali L, Pieri F, Spadazzi C, Miserocchi G, Di Menna G, Foca F, Ravaioli S, De Vita A, Cocchi C, Rossi G, Recine F, Ibrahim T. Diagnostic and predictive role of DLL3 expression in gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasms. Endocr Pathol. 2021;32:309–17.

Li B, Li X, Mao R, Liu M, Fu L, Shi L, Zhao S, Fu M. Overexpression of ODF1 in gastrointestinal tract neuroendocrine neoplasms: a novel potential immunohistochemical biomarker for well-differentiated neuroendocrine tumors. Endocr Pathol. 2021;32:301–8.

Dandpat SK, Rai SKR, Shah A, Goel N, Goel AH. Silent stellate ganglion paraganglioma masquerading as schwannoma: a surgical nightmare. J Craniovertebr Junction Spine. 2020;11:240–2.

Seth R, Ahmed M, Hoschar AP, Wood BG, Scharpf J. Cervical sympathetic chain paraganglioma: a report of 2 cases and a literature review. Ear Nose Throat J. 2014;93:E22-27.

Cadiñanos J, Llorente JL, de la Rosa J, et al. Novel germline SDHD deletion associated with an unusual sympathetic head and neck paraganglioma. Head Neck. 2011;33:1233–40.

Moyer JS, Bradford CR. Sympathetic paraganglioma as an unusual cause of Horner’s syndrome. Head Neck. 2001;23:338–42.

Erickson LA, Mete O. Immunohistochemistry in diagnostic parathyroid pathology. Endocr Pathol. 2018;29:113–29.

Tischler AS. Pheochromocytoma and extra-adrenal paraganglioma: updates. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2008;132:1272–84.

Osinga TE, Korpershoek E, de Krijger RR, et al. Catecholamine-synthesizing enzymes are expressed in parasympathetic head and neck paraganglioma tissue. Neuroendocrinology. 2015;101:289–95.

Kimura N. Dopamine β-hydroxylase: an essential and optimal immunohistochemical marker for pheochromocytoma and sympathetic paraganglioma. Endocr Pathol. 2021;32:258–61.

Kimura N, Shiga K, Kaneko KI, et al. Immunohistochemical expression of choline acetyltransferase and catecholamine-synthesizing enzymes in head-and-neck and thoracoabdominal paragangliomas and pheochromocytomas. Endocr Pathol. 2021;32:442–51.

Zhou YY, Coffey M, Mansur D, et al. Images in endocrine pathology: progressive loss of sustentacular cells in a case of recurrent jugulotympanic paraganglioma over a span of 5 years. Endocr Pathol. 2020;31:310–4.

Delfin L, Mete O, Asa SL. Follicular cells in pituitary neuroendocrine tumors. Hum Pathol. 2021;114:1–8.

Powers JF, Tischler AS. Immunohistochemical staining for SOX10 and SDHB in SDH-deficient paragangliomas indicates that sustentacular cells are not neoplastic. Endocr Pathol. 2020;31:307–9.

Mete O, Hannah-Shmouni F, Kim R, Stratakis CA. Inherited neuroendocrine neoplasms. In: Asa SL, La Rosa SL, Mete O, editors. The spectrum of neuroendocrine neoplasia. Springer: Cham; 2021. p. 409–59.

Oudijk L, Gaal J, de Krijger RR. The role of immunohistochemistry and molecular analysis of succinate dehydrogenase in the diagnosis of endocrine and non-endocrine tumors and related syndromes. Endocr Pathol. 2019;30:64–73.

Papathomas TG, Suurd DPD, Pacak K, et al. What have we learned from molecular biology of paragangliomas and pheochromocytomas? Endocr Pathol. 2021;32:134–53.

Duan K, Mete O. Hereditary endocrine tumor syndromes: the clinical and predictive role of molecular histopathology. AJSP Rev Rep. 2017;22(5):246–68.

Mete O, Pakbaz S, Lerario AM, Giordano TJ, Asa SL. Significance of alpha-inhibin expression in pheochromocytomas and paragangliomas. Am J Surg Pathol. 2021;45:1264–73.

Favier J, Meatchi T, Robidel E, et al. Carbonic anhydrase 9 immunohistochemistry as a tool to predict or validate germline and somatic VHL mutations in pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma-a retrospective and prospective study. Mod Pathol. 2020;33(1):57–64.

Udager AM, Magers MJ, Goerke DM, et al. The utility of SDHB and FH immunohistochemistry in patients evaluated for hereditary paraganglioma-pheochromocytoma syndromes. Hum Pathol. 2018;71:47–54.

Kimura N, Takayanagi R, Takizawa N, et al. Phaeochromocytoma Study Group in Japan. Pathological grading for predicting metastasis in phaeochromocytoma and paraganglioma. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2014;21:405–14.

Pierre C, Agopiantz M, Brunaud L, et al. COPPS, a composite score integrating pathological features, PS100 and SDHB losses, predicts the risk of metastasis and progression-free survival in pheochromocytomas/paragangliomas. Virchows Arch. 2019;474:721–34.

Fishbein L, Leshchiner I, Walter V, et al. Comprehensive molecular characterization of pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma. Cancer Cell. 2017;31:181–93.

Hyams VJ, Michaels L. Benign adenomatous neoplasm (adenoma) of the middle ear. Clin Otolaryngol Allied Sci. 1976;1:17–26.

Sandison A, Bell D, Thompson LDR. Middle ear adenoma. In: El-Naggar AK, Chan JKC, Grandis JR, Takata T, Slootweg PJ, editors. WHO classification of head & neck tumours. IARC: Lyon; 2017. p. 272–3.

Saliba I, Evard AS. Middle ear glandular neoplasms: adenoma, carcinoma or adenoma with neuroendocrine differentiation: a case series. Cases J. 2009;2:6508–15.

Ramsey MJ, Nadol JB, Pilch BZ, et al. Carcinoid tumor of the middle ear: clinical features, recurrences, and metastases. Laryngoscope. 2005;115:1660–6.

Torske KR, Thompson LD. Adenoma versus carcinoid tumor of the middle ear: a study of 48 cases and review of the literature. Mod Pathol. 2002;15:543–55.

Agaimy A, Lell M, Schaller T, et al. “Neuroendocrine” middle ear adenomas: consistent expression of the transcription factor ISL1 further supports their neuroendocrine derivation. Histopathol. 2015;66:182–91.

Asa SL, Arkun K, Tischler AS, et al. Middle ear “adenoma”: a neuroendocrine tumor with predominant L cell differentiation. Endocr Pathol. 2021;32:433–41.

Lott Limbach AA, Hoschar AP, Thompson LD, et al. Middle ear adenomas stain for two cell populations and lack myoepithelial cell differentiation. Head Neck Pathol. 2012;6:345–53.

Zhu J, Wang Z, Zhang Y, et al. Ectopic pituitary adenomas: clinical features, diagnostic challenges and management. Pituitary. 2020;23:648–64.

Hyrcza MD, Ezzat S, Mete O, Asa SL. Pituitary adenomas presenting as sinonasal or nasopharyngeal masses: a case series illustrating potential diagnostic pitfalls. Am J Surg Pathol. 2017;41:525–34.

Rasmussen P, Lindholm J. Ectopic pituitary adenomas. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 1979;11:69–74.

Hodgson A, Pakbaz S, Shenouda C, Francis JA, Mete O. Mixed sparsely granulated lactotroph and densely granulated somatotroph pituitary neuroendocrine tumor expands the spectrum of neuroendocrine neoplasms in ovarian teratomas: the role of pituitary neuroendocrine cell lineage biomarkers. Endocr Pathol. 2020;31:315–9.

Asa SL, Mete O, Perry A, Osamura RY. Overview of the 2022 WHO classification of pituitary tumors. Endocr Pathol. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12022-022-09703-7.

Asa SL. Challenges in the diagnosis of pituitary neuroendocrine tumors. Endocr Pathol. 2021;32:222–7.

Asa SL, Mete O, Cusimano MD, et al. Pituitary neuroendocrine tumors: a model for neuroendocrine tumor classification. Mod Pathol. 2021;34:1634–50.

Saeger W, Mawrin C, Meinhardt M, et al. Two pituitary neuroendocrine tumors (PitNETs) with very high proliferation and TP53 mutation: high-grade PitNET or PitNEC? Endocr Pathol. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12022-021-09693-y.

Hodgson A, Pakbaz S, Tayyari F, Young JEM, Mete O. Diagnostic pitfall: parathyroid carcinoma expands the spectrum of calcitonin and calcitonin gene-related peptide expressing neuroendocrine neoplasms. Endocr Pathol. 2019;30:168–72.

Feola T, Puliani G, Sesti F, et al. Laryngeal neuroendocrine tumor with elevated serum calcitonin: a diagnostic and therapeutic challenge. Case report and review of literature. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2020;11:397.

Insabato L, De Rosa G, Terracciano LM, et al. A calcitonin-producing neuroendocrine tumor of the larynx: a case report. Tumori. 1993;79:227–30.

Kuan EC, Alonso JE, Tajudeen BA, et al. Small cell carcinoma of the head and neck: a comparative study by primary site based on population data. Laryngoscope. 2017;127:1785–90.

Ohmoto A, Sato Y, Asaka N, et al. Clinicopathologic and genomic features in patients with head and neck neuroendocrine carcinoma. Mod Pathol. 2021;34:1979–89.

Bishop JA, Westra WH. Human papillomavirus-related small cell carcinoma of the oropharynx. Am J Surg Pathol. 2011;35:1679–84.

van der Laan TP, Plaat BE, van der Laan BF, et al. Clinical recommendations on the treatment of neuroendocrine carcinoma of the larynx: a meta-analysis of 436 reported cases. Head Neck. 2015;37:707–15.

Davies-Husband CR, Montgomery P, Premachandra D, et al. Primary, combined, atypical carcinoid and squamous cell carcinoma of the larynx: a new variety of composite tumour. J Laryngol Otol. 2010;124:226–9.

Bonato M, Frigerio B, Capelia C, et al. Composite enteric-type adenocarcinoma-carcinoid of the nasal mucosa. Endocr Pathol. 1993;4:40–7.

La Rosa S, Furlan D, Franzi F, et al. Mixed exocrine-neuroendocrine carcinoma of the nasal cavity: clinic-pathologic and molecular study of a case and review of the literature. Head Neck Pathol. 2013;7:76–84.

Wasserman JK, Papp S, Hope AJ, Perez-Ordóñez B. Epstein-Barr virus-positive large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the nasopharynx: report of a case with complete clinical and radiological response after combined chemoradiotherapy. Head Neck Pathol. 2018;12:587–91.

Cai Z, Lin M, Blanco AI, Liu J, Zhu H. Epstein-Barr virus-positive large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the nasopharynx: report of one case and review of the literature. Head Neck Pathol. 2019;13:313–7.

La Rosa S, Bonzini M, Sciarra A, et al. Exploring the prognostic role of Ki67 proliferative index in Merkel cell carcinoma of the skin: clinico-pathologic analysis of 84 cases and review of the literature. Endocr Pathol. 2020;31:392–400.

Moshiri AS, Doumani R, Yelistratova L, et al. Polyomavirus-negative Merkel cell carcinoma: a more aggressive subtype based on analysis of 282 cases using multimodal tumor virus detection. J Invest Dermatol. 2017;137:819–27.

Feng H, Shuda M, Chang Y, Moore PS. Clonal integration of a polyomavirus in human Merkel cell carcinoma. Science. 2008;319:1096–100.

Wong SQ, Waldeck K, Vergara IA, et al. UV-associated mutations underlie the etiology of MCV-negative Merkel cell carcinomas. Cancer Res. 2015;75:5228–34.

Goh G, Walradt T, Markarov V, et al. Mutational landscape of MCPyV-positive and MCPyV-negative Merkel cell carcinomas with implications for immunotherapy. Oncotarget. 2016;7:3403–15.

Knepper TC, Montesion M, Russell JS, et al. The genomic landscape of Merkel cell carcinoma and clinicogenomic biomarkers of response to immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2019;25:5961–71.

Leblebici C, Yeni B, Savli TC, et al. A new immunohistochemical marker, insulinoma-associated protein 1 (INSM1), for Merkel cell carcinoma: evaluation of 24 cases. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2019;40:53–8.

Kervarrec T, Tallet A, Miquelestorena-Standley E, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of a panel of immunohistochemical and molecular markers to distinguish Merkel cell carcinoma from other neuroendocrine carcinomas. Mod Pathol. 2019;32:499–510.

Bellizzi AM. SATB2 in neuroendocrine neoplasms: strong expression is restricted to well-differentiated tumours of lower gastrointestinal tract origin and is most frequent in Merkel cell carcinoma among poorly differentiated carcinomas. Histopathology. 2020;76:251–64.

Sauer CM, Haugg AM, Chteinberg E, et al. Reviewing the current evidence supporting early B-cells as the cellular origin of Merkel cell carcinoma. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2017;116:99–105.

Hoang MP, Donizy P, Wu CL, et al. TdT expression is a marker of better survival in Merkel cell carcinoma, and expression of B-cell Markers is associated with Merkel cell polyomavirus. Am J Clin Pathol. 2020;154:38–47.

Harms KL, Healy MA, Nghiem P, et al. Analysis of prognostic factors from 9387 Merkel cell carcinoma cases forms the basis for the new 8th edition AJCC staging system. Ann Surg Oncol. 2016;23:3564–71.

Paulson KG, Iyer JG, Blom A, et al. Systemic immune suppression predicts diminished Merkel cell carcinoma-specific survival independent of stage. J Invest Dermatol. 2013;133:642–6.

Higaki-Mori H, Kuwamoto S, Iwasaki T, et al. Association of Merkel cell polyomavirus infection with clinicopathological differences in Merkel cell carcinoma. Hum Pathol. 2012;43:2282–91.

Fleming KE, Ly TY, Pasternak S, et al. Support for p63 expression as an adverse prognostic marker in Merkel cell carcinoma: report on a Canadian cohort. Hum Pathol. 2014;45:952–60.

Ricci C, Morandi L, Ambrosi F, et al. Intron 4–5 hTERT DNA hypermethylation in Merkel cell carcinoma: frequency, association with other clinico-pathological features and prognostic relevance. Endocr Pathol. 2021;32:385–95.

Rivero A, Liang J. Sinonasal small cell neuroendocrine carcinoma: a systematic review of 80 patients. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2016;6:744–51.

Rooper LM, Bishop JA, Faquin WC et al. Olfactory carcinoma of the sinonasal tract: a distinctive neuroepithelial tumor pattern. Am J Surg Pathol. (Submitted).

Rindi G, Mete O, Uccella S, et al. Overview of the 2022 WHO classification of neuroendocrine neoplasms. Endocr Pathol. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12022-022-09708-2.

Funding

None. There has been no Grant support nor financial relationships pertaining to this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that this manuscript was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Ethics approval

Not applicable.

Informed Consent

The authors give consent for publication.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Mete, O., Wenig, B.M. Update from the 5th Edition of the World Health Organization Classification of Head and Neck Tumors: Overview of the 2022 WHO Classification of Head and Neck Neuroendocrine Neoplasms. Head and Neck Pathol 16, 123–142 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12105-022-01435-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12105-022-01435-8