Abstract

Bacteria isolated from thermophilic environment that can produce cellulase as well as utilise agro-waste biomass have a high potential for developing thermostable cellulase required in the biofuel industry. The cost for cellulase represents a significant challenge in converting lignocellulose to fermentable sugars for biofuel production. Among three potential bacteria examined, Bacillus licheniformis 2D55 (accession no. KT799651) was found to produce the highest cellulolytic activity (CMCase 0.33 U/mL and FPase 0.09 U/mL) at 18–24 h fermentation when grown on microcrystalline cellulose (MCC) as a carbon source in shake flask at 50 °C. Cellulase production process was further conducted on the untreated and NaOH pretreated rice straw (RS), rice husk (RH), sugarcane bagasse (BAG) and empty fruit bunch (EFB). Untreated BAG produced the highest FPase (0.160 U/mL), while the highest CMCase (0.150 U/mL) was supported on the pretreated RH. The mixture of untreated BAG and pretreated RH as agro-waste cocktail has remarkably improved CMCase (3.7- and 1.4-fold) and FPase (2.5- and 11.5-fold) compared to the untreated BAG and pretreated RH, respectively. The mechanism of cellulase production explored through SEM analysis and the location of cellulase enzymes of the isolate was also presented. Agro-waste cocktail supplementation provides an alternative method for an efficient production of cellulase.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Each year, there are millions of tonnes of lignocellulosic wastes being generated from the agricultural, agro-industrial and forestry industries, which pose a major disposal problem. On the other hand, Malaysia is very lucky to have rice straw, rice husk, oil empty fruit bunch and sugarcane bagasse as the major wastes generated from industrial boilers [1, 2]. Agro-waste material or lignocellulose consists of cellulose and hemicellulose bound together by the lignin sheath. The cellulose and hemicellulose content in agro-waste materials intended to be transformed into value-added products including biosugar, biocompost, biofuels, biochar, biocomposite and additives either through microbial fermentation, thermochemical or enzymatic process is very significant in searching for a new biological resource.

Cellulase is very crucial for biosugar in producing bioethanol due to the recalcitrant and heterologous nature of lignocellulosic materials. Cellulase hydrolyses the β-1,4-d-glucan linkages of cellulose to liberate cello-oligosaccharide, cellobiose and glucose as its major end products. These products are liberated as the result of three enzymes, namely endoglucanase (EG), which exposes the reducing and non-reducing ends of cellulose through incisions, cellobiohydrolase (EC), which acts on the reducing and non-reducing ends to liberate cello-oligosaccharide and cellobiose, while β-glucosidases cleaves cellobiose to liberate glucose for bioethanol production [3]. The major concern in utilising lignocellulose for bioethanol production is the cost of cellulase, which is usually produced from expensive substrates [3, 4]. In fact, it is still expensive despite the huge efforts given to improve its activity and productivity [5]. The utilisation of cheap and readily available agro-waste material in producing cellulase could possibly reduce its production cost and price. In addition, the cost of cellulase could be reduced by four to five times through screening, strain reconstruction and innovation in the production process [6].

To date, commercial cellulases are being produced from fungi due to the high product titre. However, due to the slow growth rate and longer fermentation period of fungi, the cost for its production is yet to be high. Thus, to meet the global demand for cellulase, bacteria cellulase was later used by many researchers due to its high growth rate, versatility, robustness, shorter generation period, genetic stability and the multienzyme complex (MEC) produced [7,8,9,10,11]. Reviews from the literature has also revealed several kinds of bacteria, mainly Bacillus [12] and actinomycetes [13] as the efficient cellulase producers. Studies over the years have also focused on using cellulase from mesophilic bacteria to carry out simultaneous saccharification and fermentation (SSF) since their enzyme activity is optimum at a temperature (40 °C) close to that of fermentative yeast (30 °C). However, the awareness on unsustainable dependence on mesophilic yeast, incompatibility in enzymatic hydrolysis and fermentation optimum temperatures and challenges such as low hydrolysis rate, high enzyme loading, high risk of contamination, low thermal stability and incomplete hydrolysis experienced during SSF have prompted recent interest in thermophilic bioprocessing. The thermophilic processing of cellulosic biomass offers several potential benefits including low viscosity, high solubility, low risk of contamination, higher hydrolysis rate, decreased enzyme loading and consumption that leads to overall economics of the process [14]. Due to the needs in high thermal industrial processes with enzyme as biocatalyst and the viability of exploring thermophilic fermentative bacteria in bioethanol production, the demand in thermostable cellulase has increased. Thermophilic cellulase degrading bacteria are said to have a great potential in developing thermostable cellulase for sustainable technologies to efficiently hydrolyse the cellulosic biomass [14]. Nonetheless, there are a very limited amount of thermophilic cellulolytic bacteria isolated from various environments as been previously reported [7, 11, 15,16,17,18].

Industries that utilise lignocellulose mostly depend on the use of a single substrate. However, as lignocellulose was being studied to search for its new industrial use due to the advocation of green technology and sustainability, the risk in inaccessibility or scarcity of specific substrate at any point in time could leave a devastating effect on industrial productivity. Combining lignocellulose has helped to improve yield [19, 20] and reduce the production cost [21] of fuel ethanol. Furthermore, mixed feedstocks (agro-waste cocktail) have been reported in the production of fermentable sugars [22, 23]. However, the use of these forms of feedstock to produce bacteria cellulase is considered rare.

For this reason, cellulose degrading bacteria were isolated and characterised from the oil palm empty fruit bunch-chicken manure compost. Since plant biomass cellulose majorly exists in crystalline form [24], it is necessary to apply microcrystalline cellulose (MCC) as a yard stick for screening the cellulase production. Therefore, a quantitative screening approach rather than the conventional CMC screening was adopted in selecting the strain that could best produce cellulase on MCC. The most productive strain was then used to examine cellulase production behaviour on a single and cocktailed agro-waste. Morphological behaviour of the strain and agro-waste was also observed to understand the mechanism of cellulolysis. Furthermore, the location(s) of the enzymes was identified to gain an insight on the enzymatic system of the bacteria strain.

Materials and Methods

Composting Feedstocks and Preparation

Shredded oil palm empty fruit bunch (OPEFB) was collected from the Seri Ulu Langat Palm Oil Mill in Dengkil, Selangor, Malaysia. Chicken manure was obtained from the poultry farm, Faculty of Agriculture, Universiti Putra Malaysia. Both feedstocks were utilised for the composting. A total of 80 kg feedstocks were mixed at the ratio of 1:1. Additionally, the required amount of water was added and mixed to achieve 55–65% moisture content. Continuous addition of water was done with turning and mixing. The temperature, pH and moisture content of the compost were also determined during a sampling period of 40 days.

Cellulolytic Bacteria Isolation

Isolation of bacteria was carried out according to that conducted by Zainudin et al. [25] with some modifications. Briefly, 10 mL of normal saline was added into a 50-mL test tube containing 1 g compost sample. The sample was properly dislodged into the mixture by agitation at 150 rpm for 10 min. One millilitre of mixture was serially diluted and plated onto Luria Bertani (LB) agar containing 1% caboxymethyl cellulose (CMC). The plates were further incubated at 37 and 55 °C for 24 h to allow mesophilic and thermophilic bacterial growth. Repeated picking and re-streaking were carried out on LB-CMC agar incubated at 37 and 55 °C for 24 h, which was then flooded with iodine solution [26]. All strains showing zone of clearance were selected as positive stains and used for further screening.

Plate Zymogram and Measurement

Cultures of 30 bacteria strain were grown in Luria Bertini (LB) broth until OD600 = 0.6. Then 5 μL of each bacteria culture was spot inoculated unto the centre of cellulase medium containing the following (g/L): 1.0 KH2PO4, 1.145 K2HPO4, 0.4 MgSO4·7H2O, 5.0 NH4SO4, 0.05 CaCl2·2H2O and 1 mL Nitsch’s trace element solution (2.2 g MnSO4, 0.5 g ZnSO4, 0.5 g H3BO3, 0.016 g CuSO4, 0.025 g Na2MoO4 and 0.046 g CoCl2) [15]. In the cellulase medium, 1% (w/v) CMC and 10 g/L bacteriological agar were added. The plates were kept undisturbed for 1 h to allow a complete diffusion, followed by incubation at 37 and 55 °C for 48 h. Later, the plate was flooded with iodine solution for 2 min [26]. The bacteria isolates were examined for CMC hydrolysis by measuring their corresponding halo zones and their hydrolytic capacity was determined by identifying the cellulolytic index using the following expression:

where EI and CI represent enzymatic index and cellulolytic index, respectively [27].

Inoculum Preparation

Each bacteria strain was cultured up to their log phase on cellulase medium containing 1% CMC. Thereafter, 50 mL of the culture was centrifuged at 10,000×g and 4 °C for 10 min. The supernatant was discarded and the cell pellet was repeatedly washed using sterile 0.1% (w/v) peptone [28]. Cell suspension was set at OD600 = 1.0 and used for inoculation process.

Quantitative Screening on Microcrystalline Cellulose

For quantitative screening, 50 mL of cellulase medium comprising 1% (w/v) MCC in 100-mL Erlenmeyer flask was introduced with 5% inoculum of bacteria cells. The flasks were incubated at 50 °C for 48 h under shaking at 180 rpm. After that, samples were withdrawn and centrifuged at 10,000×g for 10 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was taken and then used as crude enzyme to carry out enzyme activities.

Characterisation and Identification of Cellulolytic Bacteria

BIOLOG Method

Suspension of active bacterial cell culture (grown on NA at 37 °C for 16 h) was prepared in an inoculating fluid (IF-A) at a cell density of 95% transmittance using a BIOLOG turbidimeter following the manufacturer’s instruction. A 100-μL inoculum was dispensed into GEN III microplate wells using a multichannel pipette and incubated at 33 °C for 16 to 24 h after that. Oxidation of various carbon sources and their sensitivity to different chemicals indicated by the reduction in tetrazolium redox dye to purple colour was monitored and recorded on microplate reader. The pattern of oxidation was compared with the BIOLOG database software.

DNA Extraction and Molecular Phylogenetic Analysis

Genomic DNA extraction was done using GeneJet genomic DNA extraction and purification kit (Thermoscientific Inc., USA). The genomic DNA was stored at −80 °C and used as a template for 16S rDNA PCR. The 16S rDNA PCR was performed on a T-gradient thermocycler (Labrepco, Germany) with the universal primer of 27F (5′-AGA GTT TGA TCC TGG CTC AG-3′) and 1492R (5′-GGT TAC CTT GTT ACG ACT T-3′). The reaction mixture consists of 12.5 μL REDTaq, ReadyMix PCR Reaction Mix (Sigma-Aldrich, USA), 1 μL of each forward and reverse primers and 35.5 μL of sterile distilled water. The conditions for polymerase chain reaction (PCR) are 98 °C for 5 min initial denaturation, 35 cycles of 95 °C for 30 s, 45.3 °C for 30 s, 72 °C for 90 s denaturation annealing and extension and 72 °C for 8 min final extension of the amplified DNA. The PCR products were purified and sequenced. Sequence similarities were compared using the Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST) programme on NCBI and 16S rDNA gene sequence homology analysis using Gene Bank data (http://blast.ncbi.nih.gov/Blast). A phylogenetic tree was constructed using the MEGA 6.06 programme through the neighbour joining method. The partial genomic sequence was deposited with the accession number KT799651.

Pretreatment of Agro-wastes Biomass and Compositional Analysis

Rice straw was collected from a rice farm of Faculty of Agriculture, Universiti Putra Malaysia. Rice husk was obtained from Bernass Bhd. Sekinchan, Malaysia. Meanwhile, sugarcane bagasse was collected from a sugarcane extractor in a local market located at Taman Seri Serdang, Selangor, Malaysia, whereas an empty fruit bunch was accumulated from Seri Ulu Langat Palm Oil Mill in Dengkil, Selangor, Malaysia. All agro-waste biomass were thoroughly washed using tap water and dried at 60 °C to a constant weight. They were further grinded and sieved to 0.25 mm particle size using a grinder (Retsch SM 200 Rustfrei, Haan Germany). Alkali pretreatment was carried out in a volume ratio of 1:10 (1 g agricultural waste in 10 mL NaOH) with 2% NaOH, followed by autoclaving at 121 °C for 15 min. Samples were washed for several times using water and neutralised to pH 7 with HCl, then dried at 60 °C for 24 h and stored at 4 °C until further use. The analysis of cellulose, hemicellulose and lignin for both the untreated and NaOH pretreated agro-waste materials were determined according to the method described in [29].

Cellulase Production on Single Substrate and Agro-waste Cocktail

Cellulase production was carried out using 50 mL cellulase medium in 100-mL Erlenmeyer flask with composition described on ‘Plate Zymogram and Measurement’ paragraph in the ‘Material and Methods’ section containing 1% (w/v) of each agro-waste biomass. Cellulase production was carried on the untreated rice husk (URH), untreated rice straw (URS), untreated sugarcane bagasse (UBAG), untreated empty fruit bunch (UEFB), pretreated rice husk (TRH), pretreated rice straw (TRS), pretreated sugarcane bagasse (TBAG), pretreated empty fruit bunch (TEFB) and agro-waste cocktail (AWC). Bacterial cells were inoculated at 5%, which were then incubated at 50 °C for 30 h at 180 rpm. One millilitre of sample was taken at every 6 h and centrifuged at 10,000×g within 4 °C for 20 min. Meanwhile, the supernatant was used as the crude enzyme.

Enzyme Assay

The activity of crude enzyme was determined using the method described by [30]. Carboxymethyl cellulase (CMCase) activity was determined by measuring the reducing sugar released from CMC. A volume of 0.5 mL crude enzyme was put to react with 0.5 mL of 1% CMC in 0.05 M phosphate buffer with pH 7 and incubated at 50 °C for 30 min. Filter paperase (FPase) was determined by assessing the loss of sugar released by filter paper. In this reaction, 0.5 mL crude enzyme was mixed with a 1 × 6-cm (Whatman No. 1) filter paper immersed in 1.5 mL of phosphate buffer with pH 7 and incubated at 50 °C for 1 h. The reducing sugars was measured utilising the DNS method [31]. The reaction was stopped with the addition of 3 mL 3,5-dinitrosalicylic acid (DNS). One unit of enzyme activity is determined by the amount of enzyme required to liberate 1 μmol of reducing sugar per minute under assay condition. For β-glucosidase assay, p-nitrophenyl liberated from p-nitrophenyl-beta-d-glucopyranoside was spectrophotometrically determined [30]. The reaction mixture was incubated at 50 °C for 30 min. One unit of beta-glucosidase activity was defined by the amount of enzyme used in liberating 1 μmol p-nitrophenol per minute under the assay condition. For xylanase activity, the reaction mixture comprised 0.5 mL of 1% birch wood xylan in 0.05 M phosphate buffer pH 7 and 0.5 mL appropriately diluted enzyme, which was incubated at 50 °C for 30 min. Xylanase activity was determined adopting the DNS method. Meanwhile, 1 unit of xylanase activity was determined as the amount of enzyme required to liberate 1 μmol xylose per minute under specified assay condition.

Scanning Electron Microscope Analysis

Scanning electron microscopy observation was carried out using the agro-waste biomass and bacteria culture suspension. Five millilitres of Bacillus licheniformis 2D55 culture grown on UBAG, TBAG and AWC was centrifuged and processed for scanning electron microscope (SEM) analysis and referred to as cell suspension culture. The agro-waste residue was pipetted after the culture flask was allowed to sit for 20 min and then processed for SEM observation. Samples were mounted after 30 min critical point drying on a metal stubs, which was followed by gold palladium coating adopting the method by Pathan et al. [32]. Scanning electron microscope (JSM 700-151F, JOEL Tokyo, Japan) was used to observe any changes.

Localisation of Enzyme

The location of cellulase (CMCase, FPase, β-glucosidase) and xylanase produced by B. licheniformis 2D55 was identified on cellulase medium containing 1% (w/v) of AWC incubated at 50 °C under agitation at 180 rpm for 18 h. A 40-mL culture broth was centrifuged at 10,000×g for 10 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was withdrawn and applied as extracellular enzyme. The resulting cell pellet was washed three times with 15 mL 0.05 M phosphate buffer pH 7.0 and then resuspended in a 10-mL final solution of the same buffer. Cell suspension was sonicated at 40% amplitude using a sonication tool (Q Sonica QSS, Newton, CT, USA) for 8 min with 30 s pulse interval. The sonicated cell suspension was then centrifuged at 10,000×g for 10 min under 4 °C and the supernatant was withdrawn and used as intracellular enzyme sample while resuspending the cell pellet in 5 mL buffer and using it as a membrane-bound enzyme sample. The remaining AWC was further filtered through a muslin cloth with 0.2 g residue resuspended in 10 mL phosphate buffer and used as the substrate-bound enzyme sample. The enzyme samples used to analyse protein concentration as well as cellulase and xylanase activity were expressed as enzyme activity (U/mg) protein.

Protein Concentration Determination

In this study, protein concentration was quantified using Bradford assay [33]. Briefly, 100 μL of enzyme suspension was mixed with 3 mL Bradford reagent (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). The mixture was further incubated for 15 min at room temperature and read at 595 nm against a reagent blank that contains 100 μL 0.05 M phosphate buffer with pH 7 and 3 mL Bradford reagent. Using bovine serum albumin as a standard, the protein concentration was inferred from the standard curve and expressed as milligrammes per milliliter.

Results and Discussion

Co-composting of OPEFB and Chicken Manure

In composting, temperature is a crucial factor that determines the progression of this process. Findings on this study have presented that temperature has drastically rose at day 2 with its peak at 68 °C on day 4, which was then slowly declined until the end of composting process (Fig. 1). It was also observed that the high temperature was maintained for a long period (2 to 16 days) within a range of 50–68 °C. This is due to turning and metabolic activities that occurred as a result of microbial degradation. Moisture content during the composting period was found within 58 to 70%, which is in agreement with that conducted by Yahya et al. [1]. The microbial population during composting at thermophilic, mesophilic and cooling temperature were determined. The increase in microbial population at the cooling and maturing stages could be resulted from the availability of simple nutrients that may foster the re-colonisation of bacteria from the environment. Meanwhile, lower microbial count at the thermophilic stage was reported by Jurado et al. [34]. The longest composting period was found to be 136 days with a C/N ratio of 12.1 [34]. In the present study, maturity was attained within 42 days using a C/N ratio of 14.1. This result suggests that OPEFB and chicken manure are the compatible feed stocks for composting.

Screening for Cellulolytic Bacteria

A total of 60 bacterial isolates were obtained. After preliminary screening, 30 isolates were discovered positive on CMC agar with 9 of them having a high cellulolytic index (CI) ≥ 2 (Table 1). The maximum cellulolytic index of 3.8 with 100% relative activity was produced by isolate 2D55, followed by BD2 and BB16 with relative activity of 78 and 73%, respectively. Majority of isolates at the thermophilic stage was observed with a higher CI than isolate at mesophilic, cooling and stabilising temperatures. This could be attributed to the active degradation occurred at such temperatures. According to [35], higher cellulase activity was observed at thermophilic temperatures for all treatments during the composting of green waste, earthworm cast and zeolite. The three best isolates (2D55, BB16 and BD2) were selected to determine their cellulase productivity when grown on MCC as a carbon source.

Quantitative Screening for Cellulase Production on Microcrystalline Cellulose

In establishing the potential of cellulase production, isolates 2D55, BB16 and BD2 were grown in cellulose medium with microcrystalline cellulose (MCC) as the carbon source (Fig. 2). Isolate 2D55 had produced maximum CMCase activity at 0.33 U/mL and FPase activity at 0.09 U/mL after 24 h, while BD2 and BB16 have produced CMCase at 0.15 and 0.13 U/mL, respectively after 30 h. CMCase has demonstrated significantly higher activity compared to FPase in this study. The high CMCase activity observed in this study is similar to that previously reported by the studies from [14, 36]. There are very few reports on cellulase production by Bacillus sp. grown on microcrystalline cellulose as the sole carbon source [14, 15] (Table 2). However, the CMCase from isolates 2D55, BD2 and BB16 are yet to be compared in cellulase production with the chemically defined medium reported by [13]. Rastogi et al. [14] reported that CMCase (0.12 U/mL) and FPase (0.03 U/mL) were produced by thermophilic Bacillis sp. on the 9th and 8th days, respectively, when microcrystalline cellulose was used as a substrate, while Geobacillus sp. was reported to produce 0.13 U/mL CMCase and 0.04 U/mL FPase activity on the 7th and 8th days. Interestingly, the maximum cellulase production achieved in this study is between 18 and 36 h among the isolates. Cellulase production at a high rate by isolate 2D55 was identified as remarkable. Findings from this study are in contrast with the previous research, which shows that moderately thermophilic B. licheniformis B-41361 has produced CMCase on glucose and not on CMC and MCC as the carbon source [37]. Other thermophilic Bacillus sp. including Anoxybacillus and Brevibacillus sp. were reported to utilise cellulose as carbon source [17]. Isolate 2D55, which was examined with maximum cellulase titre among the isolates, was selected for further studies.

Characterisation and Identification of Bacteria Isolates

The bacteria isolates were characterised by utilising carbon source and chemical sensitivity following the BIOLOG GENIII method (Table 3), while the morphological and physiological characterisation of isolate 2D55 was done as indicated in Table 4. The isolates were found utilising dextrin, d-maltose, d-trehalose, cellobiose, d-gentiobiose, sucrose, d-turanose, l-arginine and l-glutamic acid with inhibition displayed by vancomycin. Isolates 2D55 and BB16 have demonstrated tolerance towards lithium chloride, sodium lactate and guanidine HCl with isolate BD2 showing a low tolerance. Interestingly, the ability of these three isolates to utilise cellobiose is able to influence the induction of cellulase. On the other hand, previous studies on Anoxybacillus 527 showed a higher production of cellulase on cellobiose compared to MCC [17]. Their ability to oxidise lithium chloride may also suggest their potential application in the biodegradation of lithium contaminated environment. The results obtained from the BIOLOG tool provide an easier and faster method in measuring bacterial phenotypic characteristics. It can be seen in Table 4 that isolate 2D55 is a gram-positive aerobic bacillus. It demonstrated the ability to grow within pH 3–8 in the presence of 2–8% NaCl with temperatures ranging from 30 to 60 °C. Physiological characterisation using the BIOLOG tool was also reported in a thermophilic cellulase producing Bacillus sp. strain C 1 isolated from cow dung [38].

Identification of Isolate 2D55 Using 16S rDNA

The nucleotide sequence of PCR product was compared with other sequences of 16S rDNA in the Gene Bank database by BLASTN and the accession number of KT799651 was obtained from the NCBI (Fig. 3). The phylogenetic tree generated using the neighbour joining method showed a connection between the species of B. licheniformis and Bacillus sp. The strain also showed a 99% similarity with B. licheniformis DSM13 [39]. Additionally, 2D55 presented 99% similarity with B. licheniformis 1-13AI, a gram-positive, thermophilic, aerobic, halotolerant bacterium isolated from human faeces [40] and strain B. licheniformis M1-1 isolated from enrichment cultures of composting materials at 50 °C. Therefore, strain 2D55 was considered to be highly related to different strains of B. licheniformis. Strains of Bacillus sp. that belong to Firmicutes are known to play a major role in cellulolytic and hemicellulolytic activities during lignocellulosic degradation at the thermophilic stage of composting [25].

Effects of Single/Cocktail Agro-waste on Cellulase Production by B. licheniformis 2D55

The use of agro-waste materials as the carbon sources for cellulase production has both economic and environmental advantages. The effects of using agro-waste for cellulase production were verified on rice straw, rice husk, sugarcane bagasse and empty fruit bunch. B. licheniformis 2D55 was observed to utilise both untreated and pretreated agro-waste materials for cellulase production (Table 5). For cellulase production on untreated agro-waste, the best carbon source was UBAG (CMCase 0.102 U/mL, FPase 0.160 U/mL), which was followed by the URS (CMCase 0.016 U/mL, FPase 0.018 U/mL). The minimum cellulase production (CMCase 0.004 and 0.012 U/mL) was observed on UEFB and URH, respectively. FPase activity was not produced on UEFB and URH. The cellulosic composition analysis showed a varying level of different agro-waste materials. The cellulose composition of untreated agro-waste was observed in the trend of EFB > RS > RH > BAG, while hemicellulose and lignin content showed a different trend of RH > EFB > BAG > RS.

After NaOH pretreatment, the maximum cellulase production was observed on TRH (CMCase 0.150 U/mL, FPase 0.019 U/mL), followed by TBAG (CMCase 0.090 U/mL, FPase 0.50 U/mL). The cellulase production recorded on TRS (CMCase 0.081 U/mL, FPase 0.020 U/mL) is comparable to that recorded on TEFB (CMCase 0.080 U/mL, FPase 0.010 U/mL). Since untreated BAG showed the highest FPase activity with TRH demonstrating the highest CMCase activity; hence, the combination of both substrates at 1:1 ratio was used as agro-waste cocktail (AWC) in cellulase production. Cellulase production was found to be remarkably increased on AWC (CMCase 0.380 U/mL, FPase 0.220 U/mL). Based on the maximum cellulase titres obtained on the agro-waste tested, it was observed that AWC has improved CMCase and FPase activity by 3.7 and 1.4 times better than UBAG, while a 2.5- and 11.5-fold increase in CMCase and FPase was observed in comparison with TRH. Similarly, the pretreatment of RH has significantly improved CMCase by 12.5-fold. The application of NaOH pretreatment on agro-waste biomass has improved cellulose and decreased the lignin composition of all carbon sources tested. The cellulose components decrease in the order of TRH > TBAG > TRS > TEB, hemicellulose TEFB > TRH > TRS > TBAG and lignin TEFB > TRH > TBAG > TRS.

Table 5 indicates that different agro-waste materials display different capacity for cellulase (CMCase and FPase) induction. Besides, cellulase production was notably increased on the pretreated substrates compared to the untreated one with the exception of TBAG. The high cellulase titres (FPase) observed with UBAG may be attributed from some growth promoting factors that influence the metabolism of bacteria. Lignocellulosic materials contain various proteins, amino acids and mineral elements aside from cellulose hemicellulose and lignin [41]. Gaur et al. [11] compared the cellulase production on untreated sugarcane bagasse, rice husk, rice bran, wheat bran and maize bran by a thermophilic Bacillus vallismortis RG-07. Based on their observation, sugarcane bagasse is the most suitable candidate for cellulase production, followed by rice husk and rice bran. Contrary to this, Sadhu et al. [38] reported that thermophilic Bacillus sp. supported lesser cellulase production on untreated sugarcane bagasse than on newspaper and orange scale. These observations could be due to strain behavioural differences, substrate preferences, different media compositions and processing conditions used within the studies. The ability of B. licheniformis 2D55 to produce higher titres of FPase on UBAG suggests its suitability in industrial production without incurring additional cost on the pretreatment.

The pretreatment of agro-waste material generally increases degradation, which could be due to solubilisation of lignin and hemicellulose as well as morphological and structural changes in the cellulosic fibre. In this study, the high cellulase titre (CMCase) recorded on TRH is similar to a recent observations made by Oke et al. [42] where Bacillus auerius S5.2 had produced maximum cellulase on dilute acid pretreated rice husk compared to dilute acid treated EFB and oil palm mesocarp fibre (OPF). Similarly, lower cellulase titres observed on TBAG is in line with previous study conducted by Rahnama et al. [41] that shows a lower cellulase production by Trichoderma harzanium SRN3 on NaOH pretreated rice straw than on untreated rice straw. This could also suggest that several unknown components involved in cellulase induction were affected by the pretreatment or there could be a partial disruption of crystalline cellulose portion in the BAG. Nonetheless, Brijwani and Vadlani [43] argued that the changes in hemicellulose and lignin as well as the modification of cellulose might counter the positive effects of alkali pretreatment. Furthermore, maximum cellulase production observed in AWC was supported by the studies carried out by Oke et al. [42] and Yang et al. [7], which reported higher titre of cellulase on mixed agrowaste (EFB, OPF, RH) and (CMC, wheat bran), respectively. Lower cellulase was produced when only CMC was used as the carbon source in the latter study. Surprisingly, cellulase production on the pretreated agro-waste materials was composition-related as CMCase titre and cellulose composition showed similar profiles. On the other hand, different scenario was observed on AWC. Although the pretreatment of lignocellulosic material was reported to increase the size of pore, pore volume separation of lignin from cellulose and hemicellulose has thereby improved the accessibility for bacterial degradation [44,45,46]. The results obtained in this study suggest that other nutritional factors (proteins, accessible mineral elements and possibly some sugars) present in UBAG might have given a greater influence on high cellulase productivity than cellulose composition. This is the report establishing the improvement of cellulase production by supplementing pretreated rice husk with untreated sugar cane bagasse. This strategy could reduce the pretreatment cost for producing cellulase by using agro-waste cocktail. Furthermore, the use of agro-waste cocktail for cellulase production will provide substrate security and maximise available substrates. Thus, the extreme dependency on single substrate that might result in short of supply can be avoided. Studies on other applications of combined agro-waste biomass have resulted in high product yields with respect to bioethanol production [44, 47] and saccharification [48, 49].

Figure 4 presents the enzyme production and growth profile of B. licheniformis 2D55 on AWC. Apart from CMCase and FPase, B. licheniformis 2D55 can also secrete xylanase and β-glucosidase. Maximum CMCase and FPase were identified at 18 and 24 h, while xylanase and β-glucosidase have reached their optimum titres at 12 and 30 h, respectively. Apparently, significant interest has been drawn towards xylanase due to its potential industrial applications in the hydrolysis of xylan in lignocellulose [50]. The high xylanase produced could suggest that the mechanism of cellulase production by B. licheniformis 2D55 might be obtained using xylanase to degrade the hemicellulose network in the agro-waste biomass, which could provide better accessibility to cellulose. Previous studies [51, 52] showed that a strain of B. licheniformis SVD1 grown on birch wood xylan has produced a multi enzyme complex (MEC) comprising several enzymes that include cellulase, xylanase, mannanase and pectinase. B. licheniformis 2D55 reached logarithmic phase at 6–12 h after its growth has maintained stationary within 14 to 24 h and later declined until the end of fermentation. Bacterial cells still remain metabolically active as suggested by the maximum CMCase and FPase observed at stationary phase, while optimum xylanase was produced at death phase. Previously, Rastogi et al. [14] reported a maximum CMCase production at the death phase by thermophilic Bacillus DUSELR13 with Geobacillus WSUCRF1 producing a maximum CMCase and FPase at the end of stationary phase. These results suggest that the regulatory mechanism in B. licheniformis 2D55 is different from other bacterial species. In addition, B. licheniformis 2D55 could also be producing some membrane-bound enzymes that might have assisted in increasing cellulase activity at the stationary phase. The low cell yield observed during enzyme production could be resulted from the repression of some growth proteins during thermophilic fermentation. However, it is argued that thermophiles have been shown to experience low cell yield in association with enzyme production [14].

a CMCase, FPase, xylanase, β-glucosidase production by Bacillus licheniformis 2D55 grown on agro-waste cocktail (AWC) containing a combination of untreated bagasse and pretreated rice husk ratio 1:1. Values are means of (n = 3), ±SD (vertical bars). Circle indicates xylanase activity, square CMCase activity, triangle FPase activity and diamond beta-glucosidase activity. b Growth profile of B. licheniformis 2D55 grown on agro-waste cocktail. Values are means of (n = 3), ±SD (vertical bars)

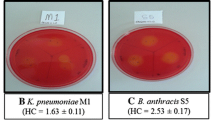

SEM Observation

SEM analysis was employed to understand the behaviour of B. lichermnifmis 2D55 especially on sugarcane bagasse and the reason cellulase production has not improved despite the pretreatment of sugarcane bagasse. The scanning electron microscopy of B. licheniformis 2D55 identified the cells as rod-shaped, motile, spore-forming bacteria. Meanwhile, their sizes were ranged from 1.45 to 0.863 μm by 0.53 to 0.156 μm. As shown in Fig. 5a, b, there are a large number of healthy cells in the cell suspension culture grown on UBAG. The cells were noticed to have secreted a network of web-like structures woven around the cells. The cell surface was observed to be rough and woolly. On the other hand, the UBAG (before inoculation) displayed a smooth, rigid and structurally intact surface (Fig. 5c). The morphology of the UBAG is similar to that previously reported [53]. Several healthy cells were attached to the UBAG residue taken from the bottom of the flask of cells grown on UBAG and the residue showed dislodges structures and cracks as a result of degradation by the bacteria (Fig. 5d). However, in Fig. 6a, which displays cell suspension of culture grown on TBAG, a more slender, unhealthy, deformed and lysed cells were observed with a leakage in the cell membrane (Fig. 6b). Figure 6c shows severe surface modification due to rough, rugged, uneven and cracks walls on the TBAG (before inoculation). Also, there is a little or no cells found attached on the TBAG culture residue (Fig. 6d, e). This demonstrates that there are many bacterial cells occupying the liquid suspension compared to the residue, hence blocking the bacteria from making a successful attachment with the substrate for cellulase induction, although the pretreatment has opened lignocellulose structure by breaking down the strong bond between cellulose, hemicellulose and lignin for better accessibility for microbial degradation. Regrettably, chemical pretreatment may also release some additional products including the products from lignin degradation such as aromatic, phenolic, polyaromatic and aldehydic compounds [54]. These products are able to inhibit bacterial growth and metabolism. For instance, phenolic compounds can cause the division and loss of integrity on the cell membrane. Consequently, cell growth, respiration and sugar assimilation are reduced [55]. This could be also related to the reduction of cellulase production observed on the TBAG substrate. Nevertheless, the bacterial cells appeared vibrant and healthier on AWC residue (Fig. 7a). The cells are mass and firmly attached compared to cells on UBAG and TBAG. A closer observation showing cell population, modification and degradation of AWC is presented in Fig. 7b. A similar SEM image was also used to support variations in cellulase production by a thermophilic Brevibacillus JXL when grown on cellulose, glucose and cellobiose [5]. According to their study, a great number of cells were found in close attachment of the cellulose residue and cell suspension. They also observed a much denser cellulosomal-like structures and higher cellulase activity when the bacteria were cultivated in glucose compared to cellobiose. Moreover, the cellulosomal structure was found in relation to cellulase production by Thermobifida fusca [56], Bacillus megaterium [57] and B. licheniformis [51]. The SEM observation in the present study does not revealed any visible cellulosomal structure; thus, it cannot be concluded that cellulosomal structure is associated with the high cellulase activity on AWC. Based on the SEM image in this study, it can be concluded that B. licheniformis 2D55 had a better growth and attachment when grown on AWC, which resulted in a higher cellulase production.

Localisation of Enzyme Produced by B. licheniformis 2D55

A study was conducted to identify the location of cellulase, xylanase and β-glucosidase activity produced by B. licheniformis 2D55 grown on AWC. This is to determine the expression patterns of enzyme in relation to cellular location in the bacteria (Fig. 8). The activity of CMCase, FPase and xylanase was found to be largely extracellular with the highest occurred in xylanase with β-glucosidase being the predominantly membrane bound. This is in agreement with the earlier production profile of enzymes in Fig. 4a where xylanase activity was observed higher than the cellulase enzyme extracellularly produced. It was argued that for cellulose degradation to be most efficient, there must be a direct contact between bacteria and substrate and that the enzyme must be secreted into the fermentation medium [58, 59]. The activity of CMCase, FPase, xylanase and β-glucosidase was also detected as intracellularly and membrane bound; however, the expression pattern was lower compared to the extracellular secretion. So far, cell-bound cellulase and xylanse have been scarcely reported in Bacillus sp. The findings of the current study have showed some dissimilarities with a previous report [60] in which CMCase, FPase and xylanase produced by Bacillus subtilis was absent in the cell debris. Cell-bound β-glucosidase has also been reported in the previous studies on Bacillus strains [60, 61]. In addition, the enzymes were still highly bounded to the membrane than intracellular location. High activity (CMCase, FPase and xylanase) was yet detected on the AWC residue even after separation. This could be resulted from the combination of extracellular enzyme residue, membrane-bound enzyme of the remaining bacterial cells in the AWC residue and those originally bounded to the substrate during cellulase production. This result corroborates the earlier SEM observation on Fig. 7a where high cell mass and close attachment of bacterial cells to the AWC were observed. Extracellular enzymes are less prone to proteolysis and can be easily extracted and purified than intracellular enzymes, hence having a more promising implication. However, cell-bound enzymes are also efficient in assisting degradation, which can potentially enhance the production of cellulase.

Conclusion

In this study, a gram-positive rod, spore-forming, aerobic, halotolerant, motile cellulase degrading thermophilic B. licheniformis 2D55 was successfully isolated from the thermophilic stage during the composting of OPEFB-chicken manure. The strain exhibited higher level of cellulase when grown on microcrystalline cellulose (MCC) compared to other isolated strains. Although a significant cellulase activity was recorded on MCC, the characteristic productivity of individual cellulase has shown a unique nature on agro-waste materials. For example, B. licheniformis 2D55 had produced higher FPase than CMCase on untreated sugarcane bagasse, while a lower FPase with higher CMCase was recorded on NaOH pretreated rice husk. Apparently, both CMCase and FPase demonstrated a remarkable improvement on agro-waste cocktail of the untreated sugarcane bagasse and pretreated rice husk. This technique has a great potential in obtaining suitable substrates to improve individual cellulase production on agro-waste materials. B. licheniformis 2D55 presented a synergistic multi-lignocellulolytic enzymes including CMCase, FPase, xylanase and β-glucosidase, which makes it potentially suitable for synergistic degradation of complex lignocellulosic substrate, a requirement in biofuel industry. Additionally, B. licheniformis 2D55 was also reported to possess active thermostable cellulase up to 60 °C during the previous study [62].

References

Yahya, A., Sye, C. P., Ishola, T. A., & Suryanto, H. (2010). Effect of adding palm oil mill decanter cake slurry with regular turning operation on the composting process and quality of compost from oil palm empty fruit bunches. Bioresource Technology, 101, 8736–8741.

Shafie, S. M., Masjuki, H. H., & Mahlia, T. M. I. (2014). Rice straw supply chain for electricity generation in Malaysia: economical and environmental assessment. Applied Energy, 135, 299–308.

Sukumaran, R. K., Singhania, R. R., & Pandey, A. (2005). Microbial cellulases-production, applications and challenges. Journal of Scientific and Industrial Research, 64, 832.

Ibrahim, M., Razak, M., Phang, L., Hassan, M., & Abd-Aziz, S. (2013). Crude cellulase from oil palm empty fruit bunch by Trichoderma asperellum UPM1 and Aspergillus fumigatus UPM2 for fermentable sugars production. Applied Biochemistry and Biotechnology, 170, 1320–1335.

Liang, Y., Yesuf, J., Schmitt, S., Bender, K., & Bozzola, J. (2009). Study of cellulases from a newly isolated thermophilic and cellulolytic Brevibacillus sp. strain JXL. Journal of Industrial Microbiology & Biotechnology, 36, 961–970.

Wang, T., Zhang, Y., Yu, H., & Wang, F. (2012). Advanced manufacturing technology in China: a roadmap to 2050. Berlin: Springer.

Yang, W., Meng, F., Peng, J., Han, P., Fang, F., Ma, L., & Cao, B. (2014). Isolation and identification of a cellulolytic bacterium from the Tibetan pig’s intestine and investigation of its cellulase production. Electronic Journal of Biotechnology, 17, 262–267.

Maki, M. L., Broere, M., Leung, K. T., & Qin, W. (2011). Characterization of some efficient cellulase producing bacteria isolated from paper mill sludges and organic fertilizers. International Journal of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, 2, 146–154.

Ladeira, S. A., Cruz, E., Delatorre, A. B., Barbosa, J. B., & Martins, M. L. L. (2015). Cellulase production by thermophilic Bacillus sp. SMIA-2 and its detergent compatibility. Electronic Journal of Biotechnology, 18, 110–115.

Vardon, D. R., Franden, M. A., Johnson, C. W., Karp, E. M., Guarnieri, M. T., Linger, J. G., & Beckham, G. T. (2015). Adipic acid production from lignin. Energy & Environmental Science, 8, 617–628.

Gaur, R., & Tiwari, S. (2015). Isolation, production, purification and characterization of an organic-solvent-thermostable alkalophilic cellulase from Bacillus vallismortis RG-07. BMC Biotechnology, 15, 19.

Lugani, Y., Singla, R., and Sooch, B.S. (2015). Optimization of cellulase production from newly isolated Bacillus sp. Y3. Journal of Bioprocessing & Biotechniques 2015.

Harun, N. A. F., Baharuddin, A. S., Zainudin, M. H. M., Bahrin, E. K., Naim, M. N., & Zakaria, R. (2012). Cellulase production from treated oil palm empty fruit bunch degradation by locally isolated Thermobifida fusca. BioResources, 8, 676–687.

Rastogi, G., Bhalla, A., Adhikari, A., Bischoff, K. M., Hughes, S. R., Christopher, L. P., & Sani, R. K. (2010). Characterization of thermostable cellulases produced by Bacillus and Geobacillus strains. Bioresource Technology, 101, 8798–8806.

Rastogi, G., Muppidi, G. L., Gurram, R. N., Adhikari, A., Bischoff, K. M., Hughes, S. R., & Sani, R. K. (2009). Isolation and characterization of cellulose-degrading bacteria from the deep subsurface of the Homestake gold mine, Lead, South Dakota, USA. Journal of Industrial Microbiology & Biotechnology, 36, 585–598.

Tai, S.-K., Lin, H.-P. P., Kuo, J., & Liu, J.-K. (2004). Isolation and characterization of a cellulolytic Geobacillus thermoleovorans T4 strain from sugar refinery wastewater. Extremophiles, 8, 345–349.

Liang, Y., Yesuf, J., & Feng, Z. (2010a). Toward plant cell wall degradation under thermophilic condition: a unique microbial community developed originally from swine waste. Applied Biochemistry and Biotechnology, 161, 147–156.

Yu, H.-Y., & Li, X. (2015). Alkali-stable cellulase from a halophilic isolate, Gracilibacillus sp. SK1 and its application in lignocellulosic saccharification for ethanol production. Biomass and Bioenergy, 81, 19–25.

Nilsson, D., & Hansson, P. A. (2001). Influence of various machinery combinations, fuel proportions and storage capacities on costs for co-handling of straw and reed canary grass to district heating plants. Biomass and Bioenergy, 20, 247–260.

Ji, L., Yu, H., Liu, Z., Jiang, J., & Sun, D. (2015). Enhanced ethanol production with mixed lignocellulosic substrates from commercial furfural and cassava residues. BioResources, 10, 1162–1173.

Thomsen, M. H., & Haugaard-Nielsen, H. (2008). Sustainable bioethanol production combining biorefinery principles using combined raw materials from wheat undersown with clover-grass. Journal of Industrial Microbiology & Biotechnology, 35, 303–311.

Lim, W.-S., & Lee, J.-W. (2013). Effects of pretreatment factors on fermentable sugar production and enzymatic hydrolysis of mixed hardwood. Bioresource Technology, 130, 97–101.

Kim, K. H., Tucker, M., & Nguyen, Q. (2005). Conversion of bark-rich biomass mixture into fermentable sugar by two-stage dilute acid-catalyzed hydrolysis. Bioresource Technology, 96, 1249–1255.

Wilson, D. B. (2011). Microbial diversity of cellulose hydrolysis. Current Opinion in Microbiology, 14, 259–263.

Zainudin, M. H. M., Hassan, M. A., Tokura, M., & Shirai, Y. (2013). Indigenous cellulolytic and hemicellulolytic bacteria enhanced rapid co-composting of lignocellulose oil palm empty fruit bunch with palm oil mill effluent anaerobic sludge. Bioresource Technology, 147, 632–635.

Kasana, R. C., Salwan, R., Dhar, H., Dutt, S., & Gulati, A. (2008). A rapid and easy method for the detection of microbial cellulases on agar plates using Gram’s iodine. Current Microbiology, 57, 503–507.

Florencio, C., Couri, S., & Farinas, C. S. (2012). Correlation between agar plate screening and solid-state fermentation for the prediction of cellulase production by Trichoderma strains. Enzyme Research, 2012, 7.

King, W., & Hurst, A. (1963). A note on the survival of some bacteria in different diluents. Journal of Applied Bacteriology, 26, 504–506.

Goering, H. K., & Van Soest, P. J. (1970). Forage fiber analysis. Agricultural hand book no.379 (pp.1–20). 591 Washington, DC: US Department of Agriculture.

Wood, T. M., & Bhat, K. M. (1988). Methods for measuring cellulase activities. Methods in Enzymology, 87–112.

Miller, G. L. (1959). Use of dinitrosalicylic acid reagent for determination of reducing sugar. Analytical Chemistry, 31, 426–248.

Pathan, A. K., Bond, J., & Gaskin, R. E. (2008). Sample preparation for scanning electron microscopy of plant surfaces —horses for courses. Micron, 39, 1049–1061.

Bradford, M. M. (1976). A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Analytical Biochemistry, 72, 248–254.

Jurado, M. M., Suárez-Estrella, F., López, M. J., Vargas-García, M.C., López-González, J. A., & Moreno, J. (2015). Enhanced turnover of organic matter fractions by microbial stimulation during lignocellulosic waste composting. Bioresource Technology, 186, 15–24.

Zhang, L., & Sun, X. (2015). Effects of earthworm casts and zeolite on the two-stage composting of green waste. Waste Management, 39, 119–129. 60839.

Ariffin, H., Hassan, M. A., Shah, U. K. M., Abdullah, N., Ghazali, F. M., & Shirai, Y. (2008). Production of bacterial endoglucanase from pretreated oil palm empty fruit bunch by Bacillus pumilus EB3. Journal of Bioscience and Bioengineering, 106, 231–236.

Bischoff, K. M., Rooney, A. P., Li, X.-L., Liu, S., & Hughes, S. R. (2006). Purification and characterization of a family 5 endoglucanase from a moderately thermophilic strain of Bacillus licheniformis. Biotechnology Letters, 28, 1761–1765.

Sadhu, S., Saha, P., Sen, S. K., Mayilraj, S., & Maiti, T. K. (2013). Production, purification and characterization of a novel thermotolerant endoglucanase (CMCase) from Bacillus strain isolated from cow dung. SpringerPlus, 2, 1.

Veith, B., Herzberg, C., Steckel, S., Feesche, J., Ouml,R., Maurer, K.H.,& Merkl, R. (2004). The complete genome sequence of Bacillus licheniformis DSM13, an organism with great industrial potential. Journal of Molecular Microbiology and Biotechnology, 7, 204–211.

Hoyles, L., Honda, H., Logan, N. A., Halket, G., La Ragione, R. M., & McCartney, A. L. (2012). Recognition of greater diversity of Bacillus species and related bacteria in human faeces. Research in Microbiology, 163, 3–13.

Rahnama, N., Mamat, S., Shah, U. K. M., Ling, F. H., Rahman, N. A. A., & Ariff, A. B. (2013). Effect of alkali pretreatment of rice straw on cellulase and xylanase production by local Trichoderma harzianum SNRS3 under solid state fermentation. BioResources, 8, 2881–2896.

Oke, M. A., Annuar, M. S. M., & Simarani, K. (2016). Enhanced endoglucanase production by Bacillus aerius on mixed lignocellulosic substrates. BioResources, 11, 5854–5869.

Brijwani, K., & Vadlani, P. V. (2011).Cellulolytic enzymes productionvia solid-state fermentation: effect of pretreatment methods on physicochemical characteristics of substrate. Enzyme research, 2011.

Barcelos, C. A., Maeda, R. N., Betancur, G. J. V., & Pereira Jr., N. (2013). The essentialness of delignification on enzymatic hydrolysis of sugar cane bagasse cellulignin for second generation ethanol production. Waste and Biomass Valorization, 4, 341–346.

Kshirsagar, S. D., Waghmare, P. R., Chandrakant Loni, P., Patil, S. A., & Govindwar, S. P. (2015). Dilute acid pretreatment of rice straw, structural characterization and optimization of enzymatic hydrolysis conditions by response surface methodology. RSC Advances, 5, 46525–46533.

Yu, C. T., Chen, W. H., Men, L. C., & Hwang, W. S. (2009). Microscopic structure features changes of rice straw treated by boiled acid solution. Industrial Crops and Products, 29, 308–315.

Erdei, B., Barta, Z., Sipos, B., Réczey, K., Galbe, M., & Zacchi, G. (2010). Ethanol production from mixtures of wheat straw and wheat meal. Biotechnology for Biofuels, 3, 1.

Moutta, R. D. O., Ferreira-Leitão, V. S., & Bon, E. P. D. S. (2014). Enzymatic hydrolysis of sugarcane bagasse and straw mixtures pretreated with diluted acid. Biocatalysis and Biotransformation, 32, 93–100.

Jensen, J., Morinelly, J., Aglan, A., Mix, A., & Shonnard, D. R. (2008). Kinetic characterization of biomass dilute sulfuric acid hydrolysis: mixtures of hardwoods, softwood, and switchgrass. AICHE Journal, 54, 1637–1645.

Bhalla, A., Bansal, N., Kumar, S., Bischoff, K. M., & Sani, R. K. (2013). Improved lignocellulose conversion to biofuels with thermophilic bacteria and thermostable enzymes. Bioresource Technology, 128, 751–759.

van Dyk, J. S., Sakka, M., Sakka, K., & Pletschke, B.I. (2010). Identification of endoglucanases , xylanases, pectinases and mannanases in the multi-enzyme complex of Bacillus licheniformis SVD1. Enzyme and Microbial Technology, 47, 112–118.

van Dyk, J. S., Sakka, M., Sakka, K., & Pletschke, B. I. (2009). The cellulolytic and hemicellulolytic system of Bacillus licheniformis SVD1 and the evidence for production of a large multi-enzyme complex. Enzyme and Microbial Technology, 45, 372–378.

Lv, D., Xu, M., Liu, X., Zhan, Z., Li, Z., & Yao, H. (2010). Effect of cellulose, lignin, alkali and alkaline earth metallic species on biomass pyrolysis and gasification. Fuel Processing Technology, 91, 903–909.

Mussatto, S. I., & Roberto, I. C. (2004). Alternatives for detoxification of diluted-acid lignocellulosic hydrolyzates for use in fermentative processes: a review. Bioresource Technology, 93, 1–10.

Palmqvist, E., & Hahn-Hägerdal, B. (2000). Fermentation of lignocellulosic hydrolysates. II: inhibitors and mechanisms of inhibition. Bioresource Technology, 74, 25–33.

Schwarz, W. (2001). The cellulosome and cellulose degradation by anaerobic bacteria. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology 56, 634–649.

Beukes, N., and Pletschke, B.I. (2006). Effect of sulfur-containing compounds on Bacillus cellulosome-associated ‘CMCase’and ‘Avicelase’activities. FEMS Microbiology Letters, 264, 226–231.

Hofsten, B.V. (1972). Microbial conversion of cellulosic wastes products. Waste recovery by microorgan661isms. UNESCO, 1–18.

Absar, N. (2009). Purification and characterization of intracellular cellulase from Aspergillus oryzae ITCC487.01. Mycobiology, 37, 121 –127.

Kim, Y.K., Lee, S.C., Cho, Y.Y., Oh, H.J., & Ko, Y. H. (2012). Isolation of cellulolytic Bacillus subtilis strains from agricultural environments. ISRN microbiology, 2012.

Zahoor, S., Javed, M., & Aftab, M. (2011). Cloning and expression of β-glucosidase gene from Bacillus licheniformis into E. coli BL 21 (DE3). Biologia, 66, 213–220.

Kazeem, M. O., Shah, U. K. M., & Baharuddin, A. S. (2016). Enhanced cellulase production by a novel thermophilic Bacillus licheniformis 2D55: characterization and application in lignocellulosic saccharification. BioResources, 11, 5404–5423.

Acknowledgements

The authors express their gratitude to the Organisation for Women in Science for the Developing World (OWSD) for providing a scholarship for this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Kazeem, M.O., Shah, U.K.M., Baharuddin, A.S. et al. Prospecting Agro-waste Cocktail: Supplementation for Cellulase Production by a Newly Isolated Thermophilic B. licheniformis 2D55. Appl Biochem Biotechnol 182, 1318–1340 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12010-017-2401-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12010-017-2401-z