Abstract

Purpose of Review

This review summarizes research on the physiological changes that occur with aging and the resulting effects on fracture healing.

Recent Findings

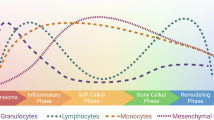

Aging affects the inflammatory response during fracture healing through senescence of the immune response and increased systemic pro-inflammatory status. Important cells of the inflammatory response, macrophages, T cells, mesenchymal stem cells, have demonstrated intrinsic age-related changes that could impact fracture healing. Additionally, vascularization and angiogenesis are impaired in fracture healing of the elderly. Finally, osteochondral cells and their progenitors demonstrate decreased activity and quantity within the callus.

Summary

Age-related changes affect many of the biologic processes involved in fracture healing. However, the contributions of such changes do not fully explain the poorer healing outcomes and increased morbidity reported in elderly patients. Future research should address this gap in understanding in order to provide improved and more directed treatment options for the elderly population.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance

Iorio R, Robb WJ, Healy WL, Berry DJ, Hozack WJ, Kyle RF, et al. Orthopaedic surgeon workforce and volume assessment for total hip and knee replacement in the United States: preparing for an epidemic. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2008;90:1598–605.

UScensus. U.S. Department of Commerce, Economics and Statistics Administration, U.S. Census Bureau, Washington. 2015. http://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/2015 Accessed 29 July 2015.

Rose S, Maffulli N. Hip fractures: an epidemiological review. Bull Hosp Jt Dis. 1999;58:197–201.

Green E, Lubahn JD, Evans J. Risk factors, treatment, and outcomes associated with nonunion of the midshaft humerus fracture. J Surg Orthop Adv. 2005;14:64–72.

Cauley JA, Thompson DE, Ensrud KC, Scott J, Black D. Risk of mortality following clinical fractures. Osteoporos Int. 2000;11:556–61.

Nieminen S, Nurmi M, Satokari K. Healing of femoral neck fractures; influence of fracture reduction and age. Ann Chir Gynaecol. 1981;70:26–31.

Geerts WH, Heit JA, Clagett GP, Pineo GF, Colwell CW, Anderson FA, et al. Prevention of venous thromboembolism. Chest. 2001;119:132S–75S.

Little DG, Ramachandran M, Schindeler A. The anabolic and catabolic responses in bone repair. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2007;89:425–33.

Hankenson KD, Zmmerman G, Marcucio R. Biological perspectives of delayed fracture healing. Injury. 2014;45:S8–S15.

Phillips AM. Overview of the fracture healing cascade. Injury. 2005;36:55–7.

Kurdy NM, Weiss JB, Bate A. Endothelial stimulating angiogenic factor in early fracture healing. Injury. 1996;27:143–5.

Hu DP, Ferro F, Yang F, Taylor AJ, Chang W, Miclau T, et al. Cartilage to bone transformation during fracture healing is coordinated by the invading vasculature and induction of the core pluripotency genes. Development. 2017;15:221–34.

Bahney CS, Hu DP, Taylor AJ, Ferro F, Britz HM, Hallgrimsson B, et al. Stem cell-derived endochondral cartilage stimulates bone healing by tissue transformation. J Bone Miner Res. 2014;29:1269–82.

Einhorn TA, Gerstenfeld LC. Fracture healing: mechanisms and interventions. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2015;11:45–54.

Lopas LA, Belkin NS, Mutyaba PL, Gray CF, Hankenson KD, Ahn J. Fracture in geriatric mice show decreased callus expansion and bone volume. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2014;472:3523–32.

Meyer RA, Tsahakis PJ, Martin DF, Banks DM, Harrow ME, Kiebzak GM. Age and ovariectomy impair both the normalization of mechanical properties and the accretion of mineral by the fracture callus in rats. J Orthop Res. 2001;19:428–35.

Bak B, Andreassen TT. The effect of aging on fracture healing in the rat. Calcif Tissue Int. 1989;45:292–7.

Bergman RJ, et al. Age-related changes in osteogenic stem cells in mice. J Bone Miner Res. 1996;11:568–77.

Gruber R, Koch H, Doll BA, Tegtmeier F, Einhorn TA, Hollinger JO. Fracture healing in the elderly patient. Exp Gerontol. 2006;41:1080–93.

Baxter M, et al. Study of telomere length reveals rapid aging of human marrow stromal cells following in vitro expansion. Stem Cells. 2004;22:675–82.

Nakahara H, Goldberg VM, Caplan AI. Culture-expanded human periosteal-derived cells exhibit osteochondral potential in vivo. J Orthop Res. 1991;9:465–76.

O'Driscoll SW, Saris DB, Ito Y, Fitzimmons JS. The chondrogenic potential of periosteum decreases with age. J Orthop Res. 2001;19:95–103.

Ferretti C, Lucarini G, Andreoni C, Salvolini E, Bianchi N, Vozzi G, et al. Human periosteal derived stem cell potential: the impact of age. Stem Cell Rev. 2015;11:487–500.

Lu C, Miclau T, Hu D, Hansen E, Tsui K, Puttlitz C, et al. Cellular basis for age-related changes in fracture repair. J Orthop Res. 2005;23:1300–7.

Abou-Khalil R, et al. Role of muscle stem cells during skeletal regeneration. Stem Cells. 2015;33:1501–11.

Brack AS, Muñoz-Cánoves P. The ins and outs of muscle stem cell aging. Skelet Muscle. 2016;6:1.

Marecic O, Tevlin R, McArdle A, et al. Identification and characterization of an injury-induced skeletal progenitor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112:9920–5.

Tevlin R, Walmsley GG, Marecic O, Hu MS, Wan DC, Longaker MT. Stem and progenitor cells: advancing bone tissue engineering. Drug Deliv Transl Res. 2016;6:159–73.

Stenderup K, Justesen J, Clausen C, Kassem M. Aging is associated with decreased maximal life span and accelerated senescence of bone marrow stromal cells. Bone. 2003;33:919–26.

Sebastian S, Andrew S, Alexandra S. Aging of mesenchymal stem cells. Ageing Res Rev. 2006;5:91–116.

Ode A, Duda GN, Geissler S, Pauly S, Ode JE, Perka C, et al. Interaction of age and mechanical stability on bone defect healing: an early transcriptional analysis of fracture hematoma in rat. PLoS One. 2014;9:e106462.

Meyer RA, Meyer MH, Tenholder M, Wondracek S, Wasserman R, et al. Gene expression in older rats with delayed union of femoral fractures. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003;85:1243–54.

Desai BJ, Meyer MH, Porter S, Kellam JF, Meyer RA Jr. The effect of age on gene expression in adult and juvenile rats following femoral fracture. J Orthop Trauma. 2003;17:689–98.

Gerstenfeld LC, Cho TJ, Kon T, Aizawa T, Cruceta J, Graves BD, et al. Impaired intramembranous bone formation during bone repair in the absence of tumor necrosis factor-alpha signaling. Cells Tissues Organs. 2001;169:285–94.

Schmidt-Bleek K, Schell H, Schulz N, Hoff P, Perka C, Buttgereit F, et al. Inflammatory phase of bone healing initiates the regenerative healing cascade. Cell Tissue Res. 2012;347:567–73.

Thomas MV, Puleo DA. Infection, inflammation, and bone regeneration: a paradoxical relationship. J Dent Res. 2011;90:1052–61.

Dishowitz MI, Mutyaba PL, Takacs JD, Barr AM, Engiles JB, Ahn J, et al. Systemic inhibition of canonical notch signaling results in sustained callus inflammation and alters multiple phases of fracture healing. PLoS One. 2013;8:e68726.

Lim JC, Ko KI, Mattos M, Fang M, Zhang C, Feinberg D, et al. TNFα contributes to diabetes impaired angiogenesis in fracture healing. Bone. 2017;99:26–38.

Franceschi C, Bonafè M, Valensin S, Olivieri F, De Luca M, Ottaviani E, et al. Inflamm-aging: an evolutionary perspective on immunosenescence. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2000;908:244–54.

Giunta B, Fernandez F, Nikolic WV, Obregon D, Rrapo E, Town T, et al. Inflammaging as a prodrome to Alzheimer’s disease. J Neuroinflammation. 2008;5:51.

Boren E, Gershwin ME. Inflamm-aging: autoimmunity, and the immune-risk phenotype. Autoimmun Rev. 2004;3:401–6.

Lencel P, Magne D. Inflammaging: the driving force in osteoporosis? Med Hypotheses. 2011;76:317–21.

• Xia S, Zhang X, Zheng S, Khanabdali R, Kalionis B, Wu J, et al. An update on inflamm-aging: mechanisms, prevention, and treatment. J Immunol Res. 2016;2016:8426874. This is an updated and an in-depth review that covers the breadth of the inflamm-aging field.

Nathan C, Ding A. Nonresolving inflammation. Cell. 2010;140:871–82.

Gruver A, Hudson L, Sempowski G. Immunosenescence of ageing. J Pathol. 2007;211:144–56.

Steinmann GG. Changes in the human thymus during aging. Curr Top Pathol. 1986;75:43–88.

Compston JE. Bone marrow and bone: a functional unit. J Endocrinol. 2002;173:387–94.

Haynes BF, Markert ML, Sempowski GD, Patel DD, Hale LP. The role of the thymus in immune reconstitution in aging, bone marrow transplantation, and HIV-1 infection. Ann Rev Immunol. 2000;18:529–60.

Xing Z, Lu C, Hu D, Yu YY, Wang X, Colnot C, et al. Multiple roles for CCR2 during fracture healing. Dis Model Mech. 2010;3:451–8.

Melton DW, Roberts AC, Wang H, Sarwar Z, Wetzel MD, Wells JT, et al. Absence of CCR2 results in an inflammaging environment in young mice with age-independent impairments in muscle regeneration. J Leukoc Biol. 2016;100:1011–25.

Xing Z, Lu C, Hu D, Miclau T 3rd, Marcucio RS. Rejuvenation of the inflammatory system stimulates fracture repair in aged mice. J Orthop Res. 2010;28:1000–6.

• Baht GS, Silkstone D, Vi L, Nadesan P, Amani Y, Whetstone H, et al. Exposure to a youthful circulation rejuvenates bone repair through modulation of β-catenin. Nat Commun. 2015;6:7131. This study demonstrated the significance of hematopoietic cells on fracture healing and the ability to improve healing in old mice with exposure to young hematopoietic cells.

Wynn TA, Chawla A, Pollard JW. Macrophage biology in development, homeostasis and disease. Nature. 2013;25:445–55.

Ferrante CJ, Leibovich SJ. Regulation of macrophage polarization and wound healing. Adv Wound Care. 2012;1:10–6.

Gordon S, Martinez FO. Alternative activation of macrophages: mechanism and functions. Immunity. 2010;32:593.

Sebastian C, Herrero C, Serra M, Lloberas J, Blasco MA, Celada A. Telomere shortening and oxidative stress in aged macrophages results in impaired STAT5a phosphorylation. J Immunol. 2009;183:2356–64.

Ramanathan R, Kohli A, Ingaramo MC, Jain A, Leng SX, Punjabi NM, et al. Serum chitotriosidase, a putative marker of chronically activated macrophages, increases with normal aging. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2013;68:1303–9.

• Duscher D, Rennert RC, Januszyk M, Anghel E, Maan ZN, Whittam AJ, et al. Aging disrupts cell subpopulation dynamics and diminishes the function of mesenchymal stem cells. Sci Rep. 2014;4:7144. This paper thoroughly showed age-related disruption of MSC function specifically related to a compromise of angiogenesis in wound healing, via in vitro, in vivo, and single-cell transcriptional analysis.

Slade Shantz JA, YY Y, Andres W, Miclau T, Marcucio R. Modulation of macrophage activity during fracture repair has differential effects in young adult and elderly mice. J Orthop Trauma. 2014;28:S10–4.

• Chang MK, Raggatt LJ, Alexander KA, Kuliwaba JS, Fazzalari NL, Schroder K, et al. Osteal tissue macrophages are intercalated throughout human and mouse bone lining tissues and regulate osteoblast function in vitro and in vivo. J Immunol. 2008;181:1232–44. This study was the first to demonstrate a resident tissue macrophage population, osteomacs that are involved in bone homeostasis and regulate osteoblast function.

Alexander KA, Chang MK, Maylin ER, Kohler T, Müller R, Wu AC, et al. Osteal macrophages promote in vivo intramembranous bone healing in a mouse tibial injury model. J Bone Miner Res. 2011;26:1517–32.

Ono T, Takayanagi H. Osteoimmunology in bone fracture healing. Curr Osteoporos Rep. 2017;15:367–75.

Könnecke I, Serra A, El Khassawna T, et al. T and B cells participate in bone repair by infiltrating the fracture callus in a two-wave fashion. Bone. 2014;64:155–65.

Sun G, Wang Y, Ti Y, Wang J, Zhao J, Qian H. Regulatory B cell is critical in bone union process through suppressing proinflammatory cytokines and stimulating Foxp3 in Treg cells. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2017;44:455–62.

Al-Sebaei MO, Daukss DM, Belkina AC, et al. Role of Fas and Treg cells in fracture healing as characterized in the Fas-deficient (lpr) mouse model of lupus. J Bone Miner Res. 2014;29:1478–91.

Nam D, Mau E, Wang Y, et al. T-lymphocytes enable osteoblast maturation via IL-17F during the early phase of fracture repair. PLoS One. 2012;7:e40044.

Prockop DJ, Oh JY. Mesenchymal stem/stromal cells (MSCs): role as guardians of inflammation. Mol Ther. 2012;20:14–20.

Caplan A, Correa D. The MSC: an injury drugstore. Cell Stem Cell. 2011;9:11–5.

Caplan A, Dennis J. Mesenchymal stem cells as trophic mediators. J Cell Biochem. 2006;98:1076–84.

Nauta AJ, Fibbe WE. Immunomodulatory properties of mesenchymal stromal cells. Blood. 2007;110:3499–506.

Kim J, Hematti P. Mesenchymal stem cell-educated macrophages: a novel type of alternatively activated macrophages. Exp Hematol. 2009;37:1445–53.

Shabbir A, Zisa D, Suzuki G, Lee T. Heart failure therapy mediated by the trophic activities of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells: a noninvasive therapeutic regimen. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2009;296:1888–97.

Uccelli A, Moretta L, Pistoia V. Mesenchymal stem cells in health and disease. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8:726–32.

Le Blanc K, Rasmusson I, Sundberg B, Götherström C, Hassan M, Uzunel M, et al. Treatment of severe acute graft versus-host disease with third party haploidentical mesenchymal stem cells. Lancet. 2004;363:1439–41.

Tögel F, Hu Z, Weiss K, Isaac J, Lange C, Westenfelder C. Administered mesenchymal stem cells protect against ischemic acute renal failure through differentiation-independent mechanisms. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2005;289:F31–42.

Colnot C, Lu C, Hu D, Helms JA. Distinguishing the contributions of the perichondrium, cartilage, and vascular endothelium to skeletal development. Dev Biol. 2004;269:55–69.

Lu C, Hansen E, Sapozhnikova A, Hu D, Miclau T, Marcucio RS. Effect of age on vascularization during fracture repair. J Orthop Res. 2008;26:1384–9.

Jacobsen KA, et al. Bone formation during distraction osteogenesis is dependent on both VEGFR1 and VEGFR2 signaling. J Bone Miner Res. 2008;23:596–609.

Prisby RD, Ramsey MW, Behnke BJ, Dominguez JM 2nd, Donato AJ, Allen MR, et al. Aging reduces skeletal blood flow, endothelium-dependent vasodilation, and NO bioavailability in rats. J Bone Miner Res. 2007;22:1280–8.

Prisby RD. Bone marrow blood vessel ossification and “microvascular dead space” in rat and human long bone. Bone. 2014;64:195–203.

Frenkel-Denkberg G, Gershon D, Levy AP. The function of hypoxia-inducible factor 1 (HIF-1) is impaired in senescent mice. FEBS Lett. 1999;462:341–4.

Wagatsuma A. Effect of aging on expression of angiogenesis-related factors in mouse skeletal muscle. Exp Gerontol. 2006;41:49–54.

Kosaki N, et al. Impaired bone fracture healing in matrix metalloproteinase-13 deficient mice. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;354:846–51.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

Daniel Clark, Mary Nakamura, and Ralph Marcucio declare no conflict of interest. This work was funded by NIH/NIA R01AG046282.

Theordore Miclau reports grants and personal fees from the Foundation for Orthopedic Trauma, grants from National Institutes of Health and Baxter, and personal fees from Depuy-Synthes, Acelity, Surrozen, and Arquos outside the submitted work.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Orthopedic Management of Fractures

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Clark, D., Nakamura, M., Miclau, T. et al. Effects of Aging on Fracture Healing. Curr Osteoporos Rep 15, 601–608 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11914-017-0413-9

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11914-017-0413-9