Abstract

Background

Recently, the laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy (LSG) has become popular as a single-stage procedure for the treatment of morbid obesity and its co-morbidities. However, the incidence of micronutrient deficiencies after LSG have hardly been researched.

Methods

From January 2005 to October 2008, 60 patients underwent LSG. All patients were instructed to take daily vitamin supplements. Patients were tested for micronutrient deficiencies 6 and 12 months after surgery.

Results

Anemia was diagnosed in 14 (26%) patients. Iron, folic acid, and vitamin B12 deficiency was found in 23 (43%), eight (15%), and five (9%) patients, respectively. Vitamin D and albumin deficiency was diagnosed in 21 (39%) and eight (15%) patients. Hypervitaminosis A, B1, and B6 were diagnosed in 26 (48%), 17 (31%), and 13 (30%) patients, respectively.

Conclusions

Due to inadequate intake and uptake of micronutrients, patients who underwent LSG are at serious risk for developing micronutrient deficiencies. Moreover, some vitamins seem to increase to chronic elevated levels with possible complications in the long-term. Multivitamins and calcium tablets should be regarded only as a minimum and supplements especially for iron, vitamin B12, vitamin D, and calcium should be added to this regimen based on regular blood testing.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

A laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy (LSG) is often used as a first-stage procedure followed either by Laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (LRYGB) or duodenal switch (DS). LSG is performed to obtain weight loss and co-morbidity reduction by restricting the food capacity of the stomach. Currently, LSG is performed less often than laparoscopic gastric banding and LRYGB, but reports of LSG used as a single procedure in morbidly obese patients are increasing [1–8].

Deficiencies in micronutrients after bariatric procedures are a known threat if not corrected appropriately [9–13]. Surprisingly, reports on anemia and micronutrient deficiencies specifically in patients who underwent LSG are scarce. As part of our standard follow-up care, we conducted this prospective study to evaluate the deficiencies in the first year following LSG.

Patients and Methods

From January 2005 to October 2008, 60 morbidly obese patients were treated with an LSG by two surgeons as a first-stage procedure towards a DS. This group of patients consisted of 36 males and 24 females with a mean age of 44 (18–70) years. Mean initial weight and body mass index (BMI) were 178 (±33.9) kg and 56.8 (±10.9) kg/m2, respectively. Demographics are shown in Table 1.

All patients underwent a LSG as a first step in order to reduce operative risks (ASA score) of the DS in the second stage. In our clinic, the gastric volume is reduced by stapling the gastric fundus and greater curvature parallel to a 36 French boogie, which is inserted in the stomach through the esophagus. Stapling starts from a distance of 3 to 5 cm from the pylorus at the greater curvature side towards the angle of His. This results in a tube-like stomach made from the lesser curvature only.

Standard laboratory evaluation was performed preoperatively consisting of a complete blood count, a mean cell volume (MCV) and kidney function. Results are shown in Table 2. After 6 and 12 months, the laboratory evaluation was repeated along with plasma iron, total iron binding capacity (TIBC), calcium, serum calcidiol (vitamin D3), parathyroid (PTH), serum retinol (vitamin A), serum thiamin (vitamin B1), serum pyridoxine (vitamin B6), serum folate (vitamin B11), and serum cobalamin (vitamin B12).

Patients were instructed to take multivitamin tablets three times daily (150% RDA). Other postoperative medication consisted of a CaD 1000/880® sachet for 1 year to prevent bone loss, Omeprazol® 40 mg once daily for 6 months to prevent ulceration of the staple lines and the remaining stomach and 5700U of Fraxiparine® once daily for 6 weeks postoperatively to prevent thrombosis.

During the first year of follow-up, six patients, none of which were anemic before surgery, underwent a DS as the second stage for the treatment for their morbid obesity. These patients were excluded for the 12-month laboratory evaluation.

Laboratory results were evaluated according to the values mentioned in Table 3. Once a deficiency was identified, it was treated accordingly. Data were prospectively collected and processed using SPSS16®. All data are reported as mean ± standard error of the mean unless otherwise specified. P < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Preoperatively, five (8.3%) patients were anemic of which one had microcytic red blood cells. Additionally, two patients without anemia were diagnosed with microcytic red blood cells.

Perioperative complications occurred in two patients. One patient had a staple line leakage that was oversewn during reoperation. A second patient developed a leakage in the staple line at the esophageal–gastric junction which was clipped endoscopically and resolved after a few months.

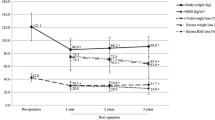

One year after surgery mean weight loss and excess BMI loss were 51 kg and 16.4 kg/m2, respectively. Mean excess weight loss was 52% (22.1–84.3%) after the first year. All patients adhered to the multivitamin supplements advised in the first year. Laboratory results are shown in Table 3.

Anemia de novo developed in ten patients during the first year. Only one patient who was anemic before surgery reached a normal Hb level with suppletion of the deficiencies found. From all new anemic patients, only two developed microcytic red blood cells. In total, 14 (26%) patients where anemic after 1 year.

Iron deficiency was found in 23 (43%) patients. From these patients, only three were diagnosed with a raised TIBC and six developed microcytic red blood cells.

Calcium levels corrected for albumin remained between acceptable levels. Two patients had slightly raised levels, with a maximum of 2.58 mmol/L. Of more concern were the high PTH levels and low levels of vitamin D found. Twenty-one (39%) patients had elevated PTH levels, and 21 (39%) patients were diagnosed with low serum vitamin D levels. This shows a fast change in bone metabolism after LSG, despite the specific medication that was prescribed for preventing bone loss.

In a number of patients, vitamin levels were above normal range. Vitamin A appeared to be high in 26 (48%) patients, vitamin B1 was high in 17 (31%) patients, and vitamin B6 was high in 13 (30%) patients. Vitamin B1, however, was also low in six (11%) patients.

Folic acid deficiency was found in eight (15%) patients and vitamin B12 deficiency in five (9%) patients. No patients developed macrocytic red blood cells during the first year.

Discussion

Deficiencies in micronutrients in morbidly obese patients are frequently diagnosed. Due to a limited diet for certain micronutrients, a great number of patients already develop these deficiencies prior to a bariatric procedure [14, 15]. Because LSG is a restrictive procedure and therefore lacks the malabsorptive component of for example a RYGB, the risk for developing deficiencies after surgery is considered low and therefore often not tested. However, because of the resection of the fundus, a number of micronutrients like iron and vitamin B12 are less likely to be absorbed, and the low risk status for developing deficiencies can be questioned [11, 16–18].

In the past, a number of publications presented data on micronutrient deficiencies found after partial gastrectomy for the treatment for ulcer disease. Iron, folate, and vitamin B12 deficiencies were most frequently reported. Long-term follow-up was advised to identify anemia, vitamin, and mineral deficiencies [19–23].

During the first year of follow-up, we found that anemia was identified in almost a third of patients. This implicates that preventing and screening for anemia and possible deficiencies leading to anemia should be one of the priorities in postoperative care. Although only eight patients developed abnormal MCVs it is likely that, with 23 (43%) patients developing iron deficiency and eight (15%) patients developing folate deficiency, these two deficiencies eventually contribute to the number of anemic patients. The iron deficiencies found can be partially explained by pre-existing shortage [14], but also by the LSG itself. Iron needs to be transformed to an absorbable form by hydrochloric acid in the normal stomach [11, 14]. The quantity of hydrochloric acid produced in the stomach is reduced and nutrients may pass the stomach faster after an LSG, thus making it more difficult to absorb iron [5]. Folic acid stores deplete quickly when intake is insufficient. This is also the most likely explanation for the eight patients (15%) who were found to have folate deficiency [24]. A normal individual has an average store of 2 mg of vitamin B12 that should last for 2 years when intake is insufficient. Morbidly obese patients have a higher risk of having a pre-existing vitamin B12 deficiency or lower storage levels, due to insufficient intake. Vitamin B12 uptake after LSG can become inadequate due to the lower production of hydrochloric acid which is needed to release bounded vitamin B12 in food [16, 17]. In the first year, five patients were diagnosed with a vitamin B12 deficiency, but it can be expected that this number will increase over the years when vitamin B12 stores have depleted.

Bone metabolism can change during the first year after LSG. Part of this change is explained by the weight loss itself due to the loss of pressure on the weight bearing bones, thus losing a potent stimulant for bone preservation. Furthermore, normal levels of vitamin D are essential for an adequate intestinal calcium uptake. A shortage in vitamin D eventually leads to a negative calcium balance and causes a compensatory rise in PTH to promote bone resorption [25, 26]. Although calcium levels were almost all within acceptable margins, 39% of the patients were diagnosed with elevated PTH levels and 39% were diagnosed with vitamin D deficiency. Suboptimal vitamin D levels (<50 nmol/L) occurred in 30 (55.5%) patients. The rise in PTH is, in some cases, most likely due to secondary hyperparathyroidism and not solely explained by a decreased uptake of calcium by insufficient calcium intake or low vitamin D levels. Albumin levels dropped in the first year resulting from protein malnutrition especially in the first months after the LSG. This is a second explanation for these results. Clearly, these patients are at risk for osteoporosis in the long-term when not corrected or treated for their calcium, vitamin D, and albumin deficiencies.

Another phenomenon arises when patients who underwent LSG are supplemented with multivitamins. Some vitamins showed a significant rise in serum levels. Serum vitamin A was elevated most frequently (48%). It is known for its function in cell differentiation and phototransduction. An excess in serum vitamin A can lead to ataxia, alopecia, dry skin, hepatotoxia, hepatomegaly, and might have an effect on bone metabolism by increasing bone resorption [27, 28]. Furthermore, high serum levels of vitamin A can be harmful in pregnant women due to the teratogenic effects on the fetus [13, 29, 30]. The serum levels in our patients, however, did not exceed 4 μmol/L after 1 year.

Vitamin B1 was low in six (11%) patients, but was found too high in 17 (31%) patients with a maximum of 230 nmol/L. Neurological abnormalities like Wernicke–Korsakoff can occur when thiamin levels are below the adequate level [11]. There has even been a report on Wernicke's encephalopathy after an LSG [31]. Reports on anaphylactic shock after intake of high doses of vitamin B1 have been published, but complications due to high levels seem rare [32, 33].

As vitamin B6 plays a role in amino acid metabolism, gluconeogenesis, and neurotransmitter synthesis, it is important to ensure adequate serum levels [32]. No patients had deficient serum vitamin B6, which is less than after a RYGB [34]. During this study, one patient developed neuropathy in hands and feet, which can be a symptom of high levels of vitamin B6 [35]. This patient had taken extra vitamin B6 on his own initiative, and serum levels had risen to seven times the maximum normal serum level. Supplements were stopped, and the symptoms vanished after a few weeks.

Conclusion

Supplementing patients is a very important part of patient care after every bariatric procedure. Balancing between low and high levels of micronutrients is a challenging part of postoperative care. In this study, a quarter of our patients were diagnosed with anemia, over 40% with iron deficiency and almost 40% with secondary hyperparathyroidism in the first year postoperative. We want to stress the risk of developing certain deficiencies after LSG, but also the risk of developing undesirable high levels of micronutrients. Our concern is that, due to the use of multivitamin tablets after LSG in the long-term, the serum levels of some potential harmful vitamins will be chronically elevated or rise towards toxic levels. The multivitamin and CaD regiment used in this study is insufficient for supplementing patients after LSG. We therefore advise to prescribe multivitamins and calcium tablets only as a minimum and to withdraw or add supplements to this regimen based on regular blood testing, especially for iron, vitamin B12, vitamin D, and calcium.

References

Dapri G, Vaz C, et al. A prospective randomized study comparing two different techniques for laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy. Obes Surg. 2007;17(11):1435–41.

Akkary E, Duffy A, et al. Deciphering the sleeve: technique, indications, efficacy, and safety of sleeve gastrectomy. Obes Surg. 2008;18(10):1323–9.

Deitel M, Crosby RD, et al. The first international consensus summit for sleeve gastrectomy (SG), New York City, October 25–27, 2007. Obes Surg. 2008;18(5):487–96.

Felberbauer FX, Langer F, et al. Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy as an isolated bariatric procedure: intermediate-term results from a large series in three Austrian centers. Obes Surg. 2008;18(7):814–8.

Melissas J, Daskalakis M, et al. Sleeve gastrectomy—a “food limiting” operation. Obes Surg. 2008;18(10):1251–6.

Nocca D, Krawczykowsky D, et al. A prospective multicenter study of 163 sleeve gastrectomies: results at 1 and 2 years. Obes Surg. 2008;18(5):560–5.

Fuks D, Verhaeghe P, et al. Results of laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy: a prospective study in 135 patients with morbid obesity. Surgery. 2009;145(1):106–13.

Nugent C, Bai C, et al. Metabolic syndrome after laparoscopic bariatric surgery. Obes Surg. 2008;18(10):1278–86.

Alvarez-Leite JI. Nutrient deficiencies secondary to bariatric surgery. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2004;7(5):569–75.

Bloomberg RD, Fleishman A, et al. Nutritional deficiencies following bariatric surgery: what have we learned? Obes Surg. 2005;15(2):145–54.

Mason ME, Jalagani H, et al. Metabolic complications of bariatric surgery: diagnosis and management issues. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2005;34(1):25–33.

Malone M. Recommended nutritional supplements for bariatric surgery patients. Ann Pharmacother. 2008;42(12):1851–8.

Guelinckx I, Devlieger R, et al. Reproductive outcome after bariatric surgery: a critical review. Hum Reprod Update. 2009;15:189–201.

Kaidar-Person O, Person B, et al. Nutritional deficiencies in morbidly obese patients: a new form of malnutrition? Part B: minerals. Obes Surg. 2008;18(8):1028–34.

Kaidar-Person O, Person B, et al. Nutritional deficiencies in morbidly obese patients: a new form of malnutrition?: Part A: vitamins. Obes Surg. 2008;8:870–6.

Behrns KE, Smith CD, et al. Prospective evaluation of gastric acid secretion and cobalamin absorption following gastric bypass for clinically severe obesity. Dig Dis Sci. 1994;39(2):315–20.

Ponsky TA, Brody F, et al. Alterations in gastrointestinal physiology after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. J Am Coll Surg. 2005;201(1):125–31.

Malinowski SS. Nutritional and metabolic complications of bariatric surgery. Am J Med Sci. 2006;331(4):219–25.

Hines JD, Hoffbrand AV, et al. The hematologic complications following partial gastrectomy. A study of 292 patients. Am J Med. 1967;43(4):555–69.

Mahmud K, Kaplan ME, et al. The importance or red cell B12 and folate levels after partial gastrectomy. Am J Clin Nutr. 1974;27(1):51–4.

Mahmud K, Ripley D, et al. Vitamin B 12 absorption tests. Their unreliability in postgastrectomy states. Jama. 1971;216(7):1167–71.

Tovey FI, Clark CG. Anaemia after partial gastrectomy: a neglected curable condition. Lancet. 1980;1(8175):956–8.

Amaral JF, Thompson WR, et al. Prospective hematologic evaluation of gastric exclusion surgery for morbid obesity. Ann Surg. 1985;201(2):186–93.

Decker GA, Swain JM, et al. Gastrointestinal and nutritional complications after bariatric surgery. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102(11):2571–80. quiz 2581.

Schweitzer DH. Mineral metabolism and bone disease after bariatric surgery and ways to optimize bone health. Obes Surg. 2007;17(11):1510–6.

Williams SE, Cooper K, et al. Perioperative management of bariatric surgery patients: focus on metabolic bone disease. Cleve Clin J Med. 2008;75(5):333–4. 336, 338 passim.

Crandall C. Vitamin A intake and osteoporosis: a clinical review. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2004;13(8):939–53.

Genaro Pde S, Martini LA. Vitamin A supplementation and risk of skeletal fracture. Nutr Rev. 2004;62(2):65–7.

Penniston KL, Tanumihardjo SA. The acute and chronic toxic effects of vitamin A. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;83(2):191–201.

Ribaya-Mercado JD, Blumberg JB. Vitamin A: is it a risk factor for osteoporosis and bone fracture? Nutr Rev. 2007;65(10):425–38.

Makarewicz W, Kaska L, et al. Wernicke’s syndrome after sleeve gastrectomy. Obes Surg. 2007;17(5):704–6.

Snodgrass SR. Vitamin neurotoxicity. Mol Neurobiol. 1992;6(1):41–73.

Parkes E. Nutritional management of patients after bariatric surgery. Am J Med Sci. 2006;331(4):207–13.

Clements RH, Katasani VG, et al. Incidence of vitamin deficiency after laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass in a university hospital setting. Am Surg. 2006;72(12):1196–202. discussion 1203–4.

Gdynia HJ, Muller T, et al. Severe sensorimotor neuropathy after intake of highest dosages of vitamin B6. Neuromuscul Disord. 2008;18(2):156–8.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Aarts, E.O., Janssen, I.M.C. & Berends, F.J. The Gastric Sleeve: Losing Weight as Fast as Micronutrients?. OBES SURG 21, 207–211 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-010-0316-7

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-010-0316-7