Abstract

Summary

A notable proportion of hip fracture patients receive nonoperative management, but such practice is seldom analysed. Although highly variable reasons underpin hip fracture nonoperative management, none of these practices conclusively outweigh the superiority of operative management. Nonoperative management should be only considered when surgery is not an option.

Purpose

Reasons underpinning hip fracture (HF) nonoperative management (NOM) are seldom analysed. This study aims to identify the reasons behind NOM and assess the accuracy of these decisions using these patients’ survival compared with those treated with operative management (OM).

Methods

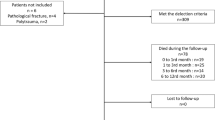

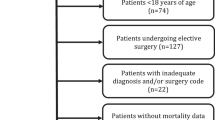

This is a retrospective cohort study based on population-wide administrative health data, including patients aged ≥ 50 with an index HF diagnosis between January 2009 and September 2017. NOM patients were subgrouped according to their expected prognoses, and their survival up to 36 months was compared with those treated surgically.

Results

From a total of 11,210 included patients, 6.8% (766) received NOM. Varying reasons lead to NOM, dividing them further into five distinct subgroups: (I) 46% NOM decision due to poor expected prognosis with OM; (II) 29% NOM decision due to poor expected prognosis for mixed reasons; (III) 15% NOM decision due to good expected prognosis with NOM; (IV) 8.0% NOM decision due to patient’s refusal of OM; and (V) 1.3% NOM decision due to occult HF. Only poor prognosis and patients who refused OM (I, II, IV) had worse survival than OM patients. However, a relatively high proportion of the poor prognosis patients survived 1 year (29%).

Conclusion

Although there was high variability in reasons underpinning HF NOM, none of these practices conclusively outweigh OM’s superiority. NOM should be considered with utmost care and only for patients for whom OM is out of the question — well-defined medical unfitness or carefully considered refusal by understanding the increased mortality risk.

Similar content being viewed by others

Data Availability

Data sharing is prohibited by the Estonian Health Insurance Fund due to the possibility of patient identification.

Code availability

The code used for analyses is available from the corresponding author on request.

Abbreviations

- CCI:

-

Charlson comorbidity index score

- EHIF:

-

Estonian Health Insurance Fund

- HF:

-

Hip fracture

- NCSP:

-

Nordic Medico-Statistical Committee’s classification of surgical procedures

- NOM:

-

Nonoperative management

- OM:

-

Operative management

References

Handoll HH, Parker MJ (2008) Conservative versus operative treatment for hip fractures in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 16:1–36. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD000337.pub2

Moulton L, Green N, Sudahar T et al (2015) Outcome after conservatively managed intracapsular fractures of the femoral neck. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 97:279–282. https://doi.org/10.1308/003588415X14181254788809

van de Ree CLP, Jongh MACD, Peeters CMM et al (2017) Hip fractures in elderly people: surgery or no surgery? a systematic review and meta-Analysis. Geriatr Orthop Surg Rehabil 8:173–180. https://doi.org/10.1177/2151458517713821

Ooi LH, Wong TH, Toh CL, Wong HP (2005) Hip fractures in nonagenarians—a study on operative and non-operative management. Injury 36:142–147. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.injury.2004.05.030

Parker M, Johansen A (2006) Hip fracture. BMJ 333:27–30. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.333.7557.27

Prommik P, Kolk H, Sarap P et al (2019) Estonian hip fracture data from 2009 to 2017: high rates of nonoperative management and high 1-year mortality. Acta Orthop 90:159–164. https://doi.org/10.1080/17453674.2018.1562816

Frenkel Rutenberg T, Vitenberg M, Haviv B, Velkes S (2018) Timing of physiotherapy following fragility hip fracture: delays cost lives. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 138:1519–1524. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00402-018-3010-1

Cram P, Yan L, Bohm E et al (2017) Trends in operative and nonoperative hip fracture management 1990–2014: a longitudinal analysis of manitoba administrative data. J Am Geriatr Soc 65:27–34. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.14538

NICE Clinical guideline CG124 (2011) The management of hip fracture in adults, Clinical guideline CG124. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg124/chapter/Recommendations#surgical-procedures. Accessed 10 November 2020

Johansen A, Golding D, Brent L et al (2017) Using national hip fracture registries and audit databases to develop an international perspective. Injury 48:2174–2179. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.injury.2017.08.001

Neuman MD, Fleisher LA, Even-Shoshan O et al (2010) Non-operative care for hip fracture in the elderly: the influence of race, income, and comorbidities. Med Care 48:314–320

(2018) National Hip Fracture Database annual report 2018. https://www.nhfd.co.uk/files/2018ReportFiles/NHFD-2018-Annual-Report-v101.pdf. Accessed 10 November 2020

Jain R, Basinski A, Kreder HJ (2003) Nonoperative treatment of hip fractures. Int Orthop 27:11–17. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00264-002-0404-y

Lim WX, Kwek EBK (2018) Outcomes of an accelerated nonsurgical management protocol for hip fractures in the elderly. J Orthop Surg 26:1–6. https://doi.org/10.1177/2309499018803408

Amrayev S, AbuJazar U, Stucinskas J et al (2017) Outcomes and mortality after hip fractures treated in Kazakhstan. Hip Int J Clin Exp Res Hip Pathol Ther 28:205–209. https://doi.org/10.5301/hipint.5000567

Penrod JD, Litke A, Hawkes WG et al (2007) Heterogeneity in hip fracture patients: age, functional status, and comorbidity. J Am Geriatr Soc 55:407–413. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01078.x

Ranhoff AH, Holvik K, Martinsen MI et al (2010) Older hip fracture patients: three groups with different needs. BMC Geriatr 10:1–7. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2318-10-65

Davies A, Tilston T, Walsh K, Kelly M (2018) Is there a role for early palliative intervention in frail older patients with a neck of femur fracture? Geriatr Orthop Surg Rehabil 9:1–6. https://doi.org/10.1177/2151459318782232

Marufu TC, Mannings A, Moppett IK (2015) Risk scoring models for predicting peri-operative morbidity and mortality in people with fragility hip fractures: qualitative systematic review. Injury 46:2325–2334. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.injury.2015.10.025

OECD County Health Profile (2019) Estonia: Country Health Profile 2019. http://www.oecd.org/publications/estonia-country-health-profile-2019-0b94102e-en.htm. Accessed 8 November 2020

The World Bank Group (2015) The state of health care integration in Estonia

Lix LM, Azimaee M, Osman BA et al (2012) Osteoporosis-related fracture case definitions for population-based administrative data. BMC Public Health 12:1–10. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-12-301

Brozek W, Reichardt B, Kimberger O et al (2014) Mortality after hip fracture in Austria 2008–2011. Calcif Tissue Int 95:257–266. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00223-014-9889-9

Diamantopoulos AP, Hoff M, Skoie IM et al (2013) Short- and long-term mortality in males and females with fragility hip fracture in Norway. A population-based study Clin Interv Aging 8:817–823. https://doi.org/10.2147/CIA.S45468

Jürisson M, Vorobjov S, Kallikorm R et al (2015) The incidence of hip fractures in Estonia, 2005–2012. Osteoporos Int 26:77–84. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-014-2820-4

Cundall-Curry DJ, Lawrence JE, Fountain DM, Gooding CR (2016) Data errors in the National Hip Fracture Database. Bone Jt J 98-B:1406–1409. https://doi.org/10.1302/0301-620X.98B10.37089

Nordic Medico-Statistical Committee (2001) NOMESCO classification of surgical procedures, Version 1.6. https://haigekassa.ee/uploads/userfiles/NCSP_1_.pdf. Accessed 4 Apr 2021

Thomas RW, Williams HLM, Carpenter EC, Lyons K (2016) The validity of investigating occult hip fractures using multidetector CT. Br J Radiol 89:. https://doi.org/10.1259/bjr.20150250

Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR (1987) A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis 40:373–383. https://doi.org/10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8

Quan H, Sundararajan V, Halfon P et al (2005) Coding algorithms for defining comorbidities in ICD-9-CM and ICD-10 administrative data. Med Care 43:1130–1139. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.mlr.0000182534.19832.83

Radley DC, Gottlieb DJ, Fisher ES, Tosteson ANA (2008) Comorbidity risk-adjustment strategies are comparable among persons with hip fracture. J Clin Epidemiol 61:580–587. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2007.08.001

Toson B, Harvey LA, Close JCT (2015) The ICD-10 Charlson comorbidity index predicted mortality but not resource utilisation following hip fracture. J Clin Epidemiol 68:44–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2014.09.017

Quan H, Li B, Couris CM et al (2011) Updating and validating the Charlson comorbidity index and score for risk adjustment in hospital discharge abstracts using data from 6 countries. Am J Epidemiol 173:676–682. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwq433

Tosteson ANA, Gottlieb DJ, Radley D et al (2007) Excess mortality following hip fracture: the role of underlying health status. Osteoporos Int J Establ Result Coop Eur Found Osteoporos Natl Osteoporos Found USA 18:1463–1472. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-007-0429-6

Quan H, Li B, Saunders LD et al (2008) Assessing validity of ICD-9-CM and ICD-10 administrative data in recording clinical conditions in a unique dually coded database. Health Serv Res 43:1424–1441. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6773.2007.00822.x

Patel K, Kay R, Rowell L (2006) Comparing proportional hazards and accelerated failure time models: an application in influenza. Pharm Stat 5:213–224. https://doi.org/10.1002/pst.213

Vochteloo AJ, Borger van der Burg BL, Mertens BJ et al (2011) Outcome in hip fracture patients related to anemia at admission and allogeneic blood transfusion: an analysis of 1262 surgically treated patients. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 12:262–268. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2474-12-262

Hu F, Jiang C, Shen J et al (2012) Preoperative predictors for mortality following hip fracture surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Injury 43:676–685. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.injury.2011.05.017

Smith T, Pelpola K, Ball M et al (2014) Pre-operative indicators for mortality following hip fracture surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Age Ageing 43:464–471. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afu065

Atzmon R, Sharfman ZT, Efrati N et al (2018) Cerebrovascular accidents associated with hip fractures: morbidity and mortality—5-year survival. J Orthop Surg 13:161–166. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13018-018-0867-1

Liu Y, Wang Z, Xiao W (2018) Risk factors for mortality in elderly patients with hip fractures: a meta-analysis of 18 studies. Aging Clin Exp Res 30:323–330. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40520-017-0789-5

Prommik P, Kolk H, Maiväli Ü et al (2020) High variability in hip fracture post-acute care and dementia patients having worse chances of receiving rehabilitation: an analysis of population-based data from Estonia. Eur Geriatr Med 11:581–601. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41999-020-00348-5

Salkeld G, Cameron ID, Cumming RG et al (2000) Quality of life related to fear of falling and hip fracture in older women: a time trade off study. BMJ 320:341–346

McDonough CM, Harris-Hayes M, Kristensen MT, et al (2021) Physical therapy management of older adults with hip fracture. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 51:CPG1–CPG81. https://doi.org/10.2519/jospt.2021.0301

Lee YH, Lim YW, Lam KS (2008) Economic cost of osteoporotic hip fractures in Singapore. Singapore Med J 49:980–984

Ryan G, Nowak L, Melo L et al (2020) Anemia at presentation predicts acute mortality and need for readmission following geriatric hip fracture. JBJS Open Access 5(e20):00048. https://doi.org/10.2106/JBJS.OA.20.00048

Norris R, Parker M (2011) Diabetes mellitus and hip fracture: a study of 5966 cases. Injury 42:1313–1316. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.injury.2011.03.021

Seitz DP, Adunuri N, Gill SS, Rochon PA (2011) Prevalence of dementia and cognitive impairment among older adults with hip fractures. J Am Med Dir Assoc 12:556–564. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2010.12.001

Hebert-Davies J, Laflamme G-Y, Rouleau D (2012) Bias towards dementia: are hip fracture trials excluding too many patients? A systematic review. Injury 43:1978–1984. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.injury.2012.08.061

McCabe JJ, Kennelly SP (2015) Acute care of older patients in the emergency department: strategies to improve patient outcomes. Open Access Emerg Med OAEM 7:45–54. https://doi.org/10.2147/OAEM.S69974

Amsellem D, Parratte S, Flecher X et al (2019) Non-operative treatment is a reliable option in over two thirds of patients with Garden I hip fractures. Rates and risk factors for failure in 298 patients. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res 105:985–990. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.otsr.2019.04.021

Gregory JJ, Kostakopoulou K, Cool WP, Ford DJ (2010) One-year outcome for elderly patients with displaced intracapsular fractures of the femoral neck managed non-operatively. Injury 41:1273–1276. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.injury.2010.06.009

Hindmarsh D, Loh M, Finch CF et al (2014) Effect of comorbidity on relative survival following hospitalisation for fall-related hip fracture in older people. Australas J Ageing 33:E1–E7. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-6612.2012.00638.x

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge Dr Pirja Sarap and Dr Egon Puuorg for their help in data validation.

Funding

This work was funded by the following projects: Interreg Baltic Sea Region Programme 2014–2020 (#R001) and the Estonian Research Council projects (TARBS14046I and PSG610).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Contributions of the authors were as follows: PP, KT, AM and HK designed the study; HK and TS validated the data; and PP and KT performed data analysis and wrote the first draft; and all five jointly revised the manuscript to its final form.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

The study was approved by the research ethics committee of the University of Tartu on 17 June 2013 (reference 227/T-12) and the Estonian Data Protection Inspectorate for the use of personalised data on 1 December 2017 (reference 2.2.-1/17/47).

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Prommik, P., Tootsi, K., Saluse, T. et al. Nonoperative hip fracture management practices and patient survival compared to surgical care: an analysis of Estonian population-wide data. Arch Osteoporos 16, 101 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11657-021-00973-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11657-021-00973-y