Abstract

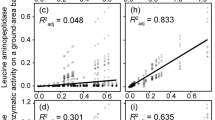

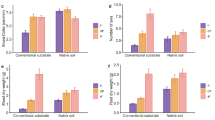

The present study aims at providing standard values for the exploration type (ET)-specific quantification of extramatrical mycelium (EMM) of ectomycorrhizal fungi applicable to ecological field studies. These values were established from mycelial systems of ectomycorrhizae (ECM) synthesized in rhizotrons with near-to-natural peat substrate. Based on image analysis, the “Specific Potential Mycelial Space Occupation” (sPMSO), i.e. the ET-specific complete area that is covered by the EMM systems (mm2 cm−1 ECM−1), and the “Specific Actual Mycelial Space Occupation” (sAMSO), i.e. the projection area of mycelial systems (mm2 cm−1 ECM−1), were analyzed as an extension of a previously described approach. The “Specific Extramatrical Mycelial Length” (sEML) [m cm−1 ECM−1] and the “Specific Extramatrical Mycelial Biomass” (sEMB) (μg cm−1 ECM−1) were calculated for each of the ET via the proportion of hyphal projected area, hyphal length and biomass, the latter two being derived from previous measurements on Piloderma croceum, a “Medium-Distance” (MD)-ET. Both sPMSO and sAMSO were highest for the “Long-Distance” (LD)-ET, whereas those of the “Short-Distance” (SD)-ET and MD-ET were similar, although showing high variation. In contrast, mycelial density per occupied area of the MD-ET was twice as high as that of the LD-ET. Proportional to the sAMSO, the EMM length and biomass differed considerably between the three ET with values of the MD-ET being 1.9 times higher than those of SD-ET, and those of the LD-ET being 15 times higher than those of the SD-ET. These standards in relation to ECM length may ease quantification of mycelial space occupation and biomass in a relatively simple way. Thereby, the ET-specific contribution of EMM can be distinguished—also of non-cultivable species—and up-scaling to large-scale estimation of cost/benefit relations is possible.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Agerer R (1987–2008) Colour atlas of ectomycorrhizae. 1st-14th del. Einhorn, Schwäbisch Gmünd

Agerer R (1991) Characterization of ectomycorrhizae. In Norris JR, Read DA, Varma AK (eds) Techniques for the study of mycorrhiza. Methods in Microbiology, vol. 23. Academic, New York, pp 25-73

Agerer R (2001) Exploration types of ectomycorrhizal mycelial systems. A proposal to classify mycorrhizal mycelial systems with respect to their ecologically important contact area with the substrate. Mycorrhiza 11:107–114

Agerer R (2002) The ectomycorrhiza Piceirhiza internicrassihyphis: a weak competitor of Cortinarius obtusus? Mycol Prog 1(3):291–299

Agerer R (2006) Fungal relationships and structural identity of their ectomycorrhizae. Mycol Prog 5(2):67–107

Agerer R (2007) Diversity of ectomycorrhizae as seen from below and above ground: the exploration types. Z Mykol 73(1):61–88

Agerer R (2009) Bedeutung der Ektomykorrhiza für Waldökosysteme. Rundgespräche der Kommission für Ökologie, Bd. 37, Ökologische Rolle von Pilzen. Pfeil, München, pp 111–121

Agerer R, Raidl S (2004) Distance related half-quantitative estimation of the extramatrical ectomycorrhizal mycelia of Cortinarius obtusus and Tylospora asterophora. Mycol Prog 3(1):57–64

Agerer R, Rambold G (2004–2009) (first posted on 2004-06-01; most recent update: 2009-01-26). DEEMY – An Information System for Characterization and Determination of Ectomycorrhizae. München, Germany. www.deemy.de/

Agerer R, Grote R, Raidl S (2002) The new method ‘micromapping’, a means to study species-specific associations and exclusions of ectomycorrhizae. Mycol Prog 1(2):155–166

Andersen CP (2003) Source-sink balance and carbon allocation below ground in plants exposed to ozone. New Phytol 157:213–228

Anderson IC, Cairney JWG (2007) Ectomycorrhizal fungi: exploring the mycelial frontier. FEMS Microbiol Rev 31(4):388–406

Bruns TD (1995) Thoughts on the processes that maintain local species diversity of ectomycorrhizal fungi. Plant Soil 170:63–73

Buée M, Vairelles D, Garbaye J (2005) Year-round monitoring of diversity and potential metabolic activity of the ectomycorrhizal community in a beech (Fagus sylvatica) forest subjected to two thinning regimes. Mycorrhiza 15:235–245

Cairney JWG, Burke RM (1996) Physiological heterogeneity within fungal mycelia: an important concept for a functional understanding of the ectomycorrhizal symbiosis. New Phytol 134:685–695

Chapin SF III, Matson PA, Mooney HA (2002) Principles of terrestrial ecosystem ecology. Springer, Berlin

Clemmensen KE, Michelsen A, Jonasson S, Shaver GR (2006) Increased ectomycorrhizal fungal abundance after long-term fertilization and warming of two arctic tundra ecosystems. New Phytol 171:391–404

Colpaert JV, van Assche JA, Luijtens K (1992) The growth of the extramatrical mycelium of ectomycorrhizal fungi and the growth responses of Pinus sylvestris L. New Phytol 120(1):127–135

Colpaert JV, van Tichelen KK (1996) Mycorrhizas and environmental stress. In Frankland JC, Magan N, Gadd GM (eds) Fungi and environmental change. Symposium of the British Mycological Society. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge pp 109-128

Donnelly DP, Boddy L, Wilkins MF (1999) Image analysis — a valuable tool for recording and analysing development of mycelial systems. Mycologist 13(3):120–125

Donnelly DP, Boddy L (2001) Mycelial dynamics during interactions between Stropharia caerulea and other cord-forming, saprotrophic basidiomycetes. New Phytol 151(3):691–704

Donnelly DP, Boddy L, Leake JR (2004) Development, persistence and regeneration of foraging ectomycorrhizal mycelial systems in soil microcosms. Mycorrhiza 14(1):37–45

Ek H (1997) The influence of nitrogen fertilization on the carbon economy of Paxillus inolutus in ectomycorrhizal association with Betula pendula. New Phytol 135:133–142

Ekblad A, Wallander H, Carlsson R, Huss-Danell K (1995) Fungal biomass in roots and axtramatrical mycelium in relation to macronutrients and plant biomass of ectomycorrhizal Pinus sylvestris and Alnus incana. New Phytol 131:443–451

Finlay R, Söderström B (1992) Mycorrhiza and carbon flow to the soil. In: Allen MJ (ed) Mycorrhizal functioning. Chapman & Hall, New York, pp 135–160

Genney DR, Anderson IC, Alexander IJ (2006) Fine-scale distribution of pine ectomycorrhizas and their extramatrical mycelium. New Phytol 170:381–390

Hedh J, Wallander H, Erland S (2008) Ectomycorrhizal mycelial species composition in apatite amended and non amended mesh bags buried in a phosphorus poor spruce forest. Mycol Res 112:681–688

Hendricks JJ, Mitchell RJ, Kuehn KA, Pecot SD, Simms SE (2006) Measuring external mycelia production of ectomycorrhizal fungi in the field: the soil matrix matters. New Phytol 171:179–186

Hobbie EA (2006) Carbon allocation to ectomycorrhizal fungi correlates with belowground allocation in culture studies. Ecology 87:563–569

Hobbie EA, Agerer R (2010) Nitrogen isotopes in ectomycorrhizal sporocarps correspond to belowground exploration types. Plant Soil 327:71–83

Högberg MN, Högberg P (2002) Extramatrical ectomycorrhizal mycelium contributes one-third of microbial biomass and produces, together with associated roots, half the dissolved organic carbon in a forest soil. New Phytol 154:791–795

Holmgren PK, Holmgren NH, Barnett LC (1990) Index Herbariorum, Part I. Herbaria of the World. 8th edn. [Regnum Vegetabile No. 120.]. New York Botanical Garden, New York. (http://www.nybg.org/bsci/ih/ih.html)

Hortal S, Pera J, Parladé J (2008) Tracking mycorrhizas and extraradical mycelium of the edible fungus Lactarius deliciosus under field competition with Rhizopogon spp. Mycorrhiza 18(2):69–77

Jones MD, Durall DM, Tinker PB (1990) Phosphorus relationship and production of extramatrical hyphae by two types of willow ectomycorrhizas at different soil phosphorus levels. New Phytol 115(2):259–268

Kammerbauer H, Agerer R, Sandermann H (1989) Studies on ectomycorrhiza XXII. Mycorrhizal rhizomorphs of Thelephora terrestris and Pisolithus tinctorius in association with Norway spruce (Picea abies): formation in vitro and translocation of phosphate. Trees 3:78–84

Kennedy PG, Peay KG, Bruns TD (2009) Root tip competition among ectomycorrhizal fungi: Are priority effects a rule or an exception? Ecology 90:2098–2107

Kjøller R (2006) Disproportionate abundance between ectomycorrhizal root tips and their associated mycelia. FEMS Microbiol Ecol 58:214–224

Klamer M, Bååth E (2004) Estimation of conversion factors for fungal biomass determination ion compost using ergosterol and PLFA 18:2 omega 6,9. Soil Biol Biochem 36:57–65

Landeweert R, Veenman C, Kuyper TW, Fritze H, Wernars K, Smit E (2003) Quantification of ectomycorrhizal mycelium in soil by real-time PCR compared to conventional quantification techniques. FEMS Microbiol Ecol 45:283–292

Leake J, Johnson D, Donelly D, Muckle G, Boddy L, Read D (2004) Networks of power and influence: the role of mycorrhizal mycelium in controlling plant communities and agroecosystems. Can J Bot 82(8):1016–1045

López-Mondéjar R, Antón A, Raidl S, Ros M, Pascual JA (2010) Quantification of the biocontrol agent Trichoderma harzianum with real-time TaqMan PCR and its potential extrapolation to the hyphal biomass. Bioresour Technol 101(8):2888–2891

Majdi H, Truus L, Johansson U (2008) Effects of slash retention and wood ash addition on fine root biomass and production and fungal mycelium in a Norway spruce stand in SW Sweden. For Ecol Manage 255:2109–2117

Markkola AM, Othonen R, Tarvainen O, Ahonen-Jonnarth U (1995) Estimates of fungal biomass in Scots pine stands on an urban pollution gradient. New Phytol 131:139–147

Martin PM (1996) The genus Rhizopogon in Europe. Edicions especials de la Societat Catalana de Micologia 5, Barcelona

Marx DH (1969) The influence of ectotrophic mycorrhizal fungi on the resistance of pine roots to pathogenic infections: I. Antagonism of mycorrhizal fungi to root pathogenic fungi and soil bacteria. Phytopathology 59:153–163

Moser M (1987) Basidiomyceten II. Röhrlinge und Blätterpilze (Agaricales). Kleine Kryptogamenflora. II/b2. 2nd edition. Stuttgart

Newton AC (1992) Towards a functional classification of ectomycorrhizal fungi. Mycorrhiza 2:75–79

Nilsson LO, Giesler R, Bååth E, Wallander H (2005) Growth and biomass of mycorrhizal mycelia in coniferous forests along short natural nutrient gradients. New Phytol 165:613–622

Nye PH, Tinker PB (1977) Solute movement in the soil-root system. Studies in Ecology 4. Blackwell, Oxford

Parrent JL, Vilgalys R (2007) Biomass and compositional responses of ectomycorrhizal fungal hyphae to elevated CO2 and nitrogen fertilization. New Phytol 176:164–174

Parladé J, Hortal S, Pera J, Galipienso L (2007) Quantitative detection of Lactarius deliciosus extraradical soil mycelium by real-time PCR and its application in the study of fungal persistence and interspecific competition. J Biotechnol 128:14–23

Peterson RL, Chakravarty P (1991) Techniques in synthesizing ectomycorrhiza. In: Norris JR, Read DJ, Varma AK (eds) Techniques for the study of mycorrhiza. Methods Microbiol 23:75–106

Pritsch K, Raidl S, Marksteiner E, Blaschke H, Agerer R, Schloter M, Hartmann A (2004) A rapid and highly sensitive method for measuring enzyme activities in single mycorrhizal tips using 4-methylumbelliferone-labelled fluorogenic substrates in a microplate system. J Microbiol Meth 58:233–241

Raidl S (1997) Studien zur Ontogenie an Rhizomorphen von Ektomykorrhizen. Bibliotheca Mycologica, vol 169. Cramer, Berlin

Raidl S, Bonfigli R, Agerer R (2005) Calibration of quantitative real-time TaqMan PCR by correlation of hyphal biomass and ITS copies in mycelia of Piloderma croceum. Plant Biol 7:713–717

Read DJ (1992) The mycorrhizal mycelium. In: Allen MF (ed) Mycorrhizal functioning. An integrative plant-fungal process. Chapman & Hall, New York, pp 102–133

Rosling A, Rosenstock N (2008) Ectomycorrhizal fungi in mineral soil. Mineralog Mag 72:127–130

Rousseau JV, Sylvia DM, Fox AJ (1994) Contribution of ectomycorrhiza to the potential nutrient absorbing surface of pine. New Phytol 128(639):644

Rygiewicz PT, Andersen CP (1994) Mycorrhiza alter quality and quantity of carbon allocated below ground. Nature 369:58–60

Schubert R, Raidl S, Funk R, Bahnweg G, Müller-Starck G, Agerer R (2003) Quantitative detection of the ectomycorrhizal fungus Piloderma croceum Erikss. & Hjortst. by fluorescent polymerase chain reaction in comparison with direct observation methods. Mycorrhiza 13:159–165

Simard SW, Perry DA, Smith JE, Molina R (1997) Effects of soil trenching on occurrence of ectomycorrhizas on Pseudotsuga menziesii seedlings in mature forests of Betula papyrifera and Pseudotsuga menziesii. New Phytol 136(2):327–340

Smith SE, Read DJ (2008) Mycorrhizal symbiosis, 3rd edn. Academic, San Diego

Söderström B (2002) Challenges for mycorrhizal research into the new millennium. Plant Soil 244:1–7

Stalpers JA (1993) The Aphyllophoraceous fungi I. Keys to the species of the Thelephorales. Stud Mycol 35:1–168

Wallander H (2000) Uptake of P from apatite by Pinus sylvestris seedlings colonised by different ectomycorrhizal fungi. Plant Soil 218:249–256

Wallander H, Nilsson LO, Hagerberg D, Bååth E (2001) Estimation of the biomass and seasonal growth of external mycelium of ectomycorrhizal fungi in the field. New Phytol 151:753–760

Wallander H, Mahmood S, Hagerberg D, Johansson L, Pallon J (2003) Elemental composition of ectomycorrhizal mycelia identified by PCR-RFLP analysis and grown in contact with apatite or wood ash in forest soil. FEMS Microbiol Ecol 44:57–65

Wallander H (2006) External mycorrhizal mycelia – the importance of quantification in natural ecosystems. New Phytol 171:240–242

Wallander H, Johansson U, Sterkenburg E, Brandström Durling M, Lindahl BD (2010) Production of ectomycorrhizal mycelium peaks during canopy closure in Norway spruce forests. New Phytol 187:1124–1134

Weigt R, Raidl S, Verma R, Rodenkirchen H, Göttlein A, Agerer R (2010) Effects of twice-ambient carbon dioxide and nitrogen amendment on biomass, nutrient contents and carbon costs of Norway spruce seedlings as influenced by mycorrhization with Piloderma croceum and Tomentellopsis submollis. Mycorrhiza (published online, doi:10.1007/s00572-010-0343-1)

Werner H, Fabian P (2002) Free-air fumigation of mature trees. Environ Sci Pollut Res 9:117–121

Wu B, Nara K, Hogetsu T (1999) Competition between ectomycorrhizal fungi colonizing Pinus densiflora. Mycorrhiza 9(3):151–159

Acknowledgment

This study was supported by the German Research Foundation (DFG) in the frame of the interdisciplinary research program “Growth and Parasite Defense” (SFB607, project B7).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

An erratum to this article can be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11557-011-0772-z.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Weigt, R.B., Raidl, S., Verma, R. et al. Exploration type-specific standard values of extramatrical mycelium – a step towards quantifying ectomycorrhizal space occupation and biomass in natural soil. Mycol Progress 11, 287–297 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11557-011-0750-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11557-011-0750-5