Abstract

Indefinites display a great functional variety and they give rise to different pragmatic effects. We focus on free choice indefinites and in particular on the Italian qualsiasi. Our aim is to reconstruct the grammaticalization path of this item and understand how diachronic data might shed some light on existing semantic theories of free choice. We employ corpus-based tools to build a database containing occurrences of qualsiasi from its origin and early forms to its current usage. We show that qualsiasi emerged from a particular unconditional construction and we outline the different stages which led to its grammaticalization. We analyze the compatibility of our diachronic study with formal accounts of free choice inferences, with a focus on Alternative Semantics analyses for indefinite pronouns and so-called grammatical theories of free choice. Our work shows that an integration between formal semantics and historical linguistics is fruitful and worth pursuing.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Most languages show a fairly uniform morphosyntactic behaviour of indefinite expressions.Footnote 1 For instance, indefinites are either derived from interrogative structures by means of an indefinite marker (e.g. the Latin quidam, ‘someone’), or they are formed from an indefinite marker together with a general ontological-category noun (e.g. the English any-series). On the other hand, indefinites display a variety of functional distinctions, which are related to each other in a complex, but cross-linguistically interrelated, way. To see this, consider the contrast in ‘Someone/anyone knows the answer.’ While someone indicates that there is a specific person who knows the answer, anyone has clearly a non-specific flavour. In Haspelmath’s (1997) terms, this amounts to the distinction between specificity versus non-specificity. Another important function, exemplified in (1a), is the Free Choice function (fc):

In (1a) the speaker, besides claiming that John can take something, informs the addressee that all options are permitted possibilities. In this case, we say that the indefinite pronoun anything expresses the fc function.

As noted by Haspelmath (1997), a salient feature of indefinite pronouns, and fc ones in particular, is their short lifespan, since they do not tend to be stable elements of the grammar.Footnote 2 This implies that indefinite expressions can in principle lose existing functions or acquire new ones, as well as shift from being marginal to common in a given language.

In a few points of his work, Haspelmath (1997) outlined, based solely on etymological considerations, a diachronic typology of indefinite pronouns, explaining how they might arise and change over time across different languages. To our knowledge, with the exception of Aguilar-Guevara et al. (2011), de Vos (2010) and Aloni (2017), there is no previous work which tried to empirically study the grammaticalization paths of fc indefinites by looking at the diachronic evolution of specific items.Footnote 3

Existing semantic accounts of free choice have all their merits and each of them contributes to our understanding of free choice phenomena.Footnote 4 However, none of them takes into serious consideration diachronic aspects in their analyses or at least try to link diachronic considerations to the salient proprieties and distribution of fc indefinites.Footnote 5 As noted above, indefinite expressions constitute a dynamic environment and understanding how they develop in different forms across languages and acquire a grammatical status can potentially lead to new insights for the semantic debate as well.

In the present work, we will describe the diachronic development of the Italian indefinite determiner qualsiasi, which exhibits free choice functions. There are at least three reasons to engage in such study. First, it will provide us with a detailed description of the development of an Italian indefinite determiner, which is, independently of our goals, a relevant contribution to the field of historical linguistics. Second, language change is not only important for descriptive purposes, but it is a fundamental aspect of human language. Understanding how language changes is crucial for understanding what language is. Lastly the synchronic picture of language is, after all, the result of its diachronic phases. As we will see, our diachronic findings will shed light on some aspects of existing semantics accounts of fc indefinites. This means that formal semanticists, usually concerned only with the synchronic picture of language,Footnote 6 can potentially benefit from insights related to diachronic linguistics.

This paper is structured as follows. Section 2 contains some general considerations on the Italian system of fc indefinites and elaborates on the reasons which led us to take into consideration the indefinite qualsiasi and not others. Section 3 contains our corpus study and Sect. 4 discusses our diachronic results. Section 5 outlines how the emergence of the fc indefinite qualsiasi occurred. In Sect. 6 we discuss how our data might be interpreted in light of existing semantic accounts of free choice. Section 7 concludes, explaining how the empirical adequacy of semantic theories should not be simply measured synchronically, but also diachronically.

2 Italian free choice indefinites and qualsiasi

2.1 Outline of Italian fc indefinite pronouns

The Italian language exhibits a great variety of indefinite pronouns and determiners. With particular regard to fc indefinites, the most common ones are described in Table 1.

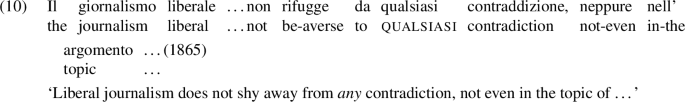

Due to the early origin of -unque Italian indefinites, it would be difficult, if not impossible, to conduct a comprehensive diachronic study for those items. Moreover, in current Italian qualsiasi is a far more common indefinite than qualsivoglia, which is normally used for emphatic or marked purposes. Consider also the frequency graph in Fig. 1, based on the 2019 Italian corpus of Google Ngram Viewer:Footnote 7

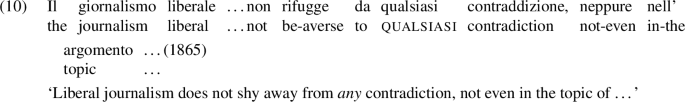

The graph above confirms how dynamic the environment of fc indefinites is. This implies that analyzing how these items developed is crucial to their correct understanding. It is important to note that these shifts would not be surprising in the case of ‘content’ words, which may simply change due to sociological reasons.Footnote 8 Indefinite pronouns are functional elements and belong to the grammar, which we might expect to be fairly stable. In particular, the focus of our work will be on the indefinite qualsiasi. We believe that studying the development of an item lately introduced in the Italian vocabulary, and whose occurrence shifted from being rarely present to being the most common indefinite pronoun, might provide useful insights with regard to its evolution and semantic changes.

2.2 Introduction to qualsiasi

Qualsiasi is a compound word originated from the wh-element ‘qual(e)’ and ‘siasi’ (the present subjunctive ‘sia’ of the verb to be, and the 3rd singular person enclitic ‘si’). According to the Italian dictionary by De Mauro (2000), the first occurrence of qualsiasi dates back to the year 1610, even though, as we will see, in our corpus study we found only three examples before the 19th century. Since the presence of qualsiasi was scarce, we also took into consideration the diachronic development of the proclitic form qualsisia, where the clitic ‘si’ precedes ‘sia’, which is significantly more common than qualsiasi in the 17th century, and mostly absent after the 18th century, if not as a form of archaism. Moreover, we also investigated the whole expression qual si sia, from which the compound forms were originated according to the Italian historical dictionary by Battaglia and Barberi Squarotti (2002).

The presence of the wh-element qual might suggest that the first environment in which qual appeared together with si and sia was a direct or indirect interrogative clause like (2), from a letter of Michelangelo Buonarroti:Footnote 9

In (2) we observe that the usage of si seems to have a strengthening effect on the whole utterance, but it does not play an essential role in the corresponding argument structure of sia and it can be potentially omitted.Footnote 10 Admittedly, an indirect interrogative clause like (2) does not seem to be related with the meaning of fc.Footnote 11 Consequently, if we want to understand where the free choice reading originated, we have to look elsewhere. Some verses, in this regard, might provide an interesting insight. Consider (3), from the Italian poet Francesco Petrarca, active in the first part of 1300s.

Even if (3) contains the first-person singular clitic mi, and not si, we observe that the combination qual + clitic + present subjunctive of to be can be used in the concessive construction ‘qual io mi sia’.Footnote 12 As the paraphrase in (3) shows, this resembles the generalizing or free choice reading typical of the indefinites under investigation. This seems to get us on the right track. Let us see if and how data from diachronic corpora are in line with these preliminary remarks.

3 Diachronic study

In this section we introduce the corpora and the data used in our study. Our diachronic study comprised four resources ranging from the 10th century to the year 2019:

-

1.

OVI (Opera del Vocabolario Italiano):Footnote 13

corpus of Old Italian ranging from the 10th century to end of the 14th century. It includes 24 billion words (occurrences) from roughly 2000 texts.

-

2.

M.I.DIA. (Morfologia dell’Italiano in DIAcronia):Footnote 14

corpus of written Italian with a temporal distribution between the beginning of the 12th century and the year 1947. It contains 7.5 billion occurrences from 800 texts.

-

3.

LIS (Lessico dell’Italiano Scritto):Footnote 15

corpus of written Italian from 1861 to 2001 with a total of 25 billion occurrences.

-

4.

Corriere della Sera:Footnote 16

Italian daily newspaper founded in 1876. We extracted the data from the online version of the newspaper from 2000 to 2019.

As said before, due to the origin of qualsiasi, the following items were analyzed: qualsiasi, qualsisia and qual si sia. Unfortunately, only single-word queries were possible in M.I.DIA. In order to obtain the results of qual si sia, we searched all the occurrences of qual and we obtained the desired examples by standard regular expression techniques. Among our corpora, only M.I.DIA. allowed for downloading the results in CSV format. In the other cases, the examples were manually added from a random selection.

3.1 Annotation

Each example was labelled according to the scheme in Table 2, which corresponds to (4).

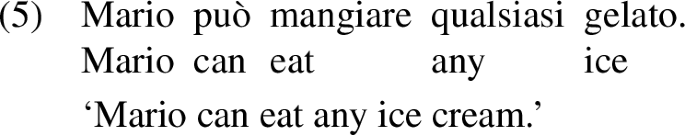

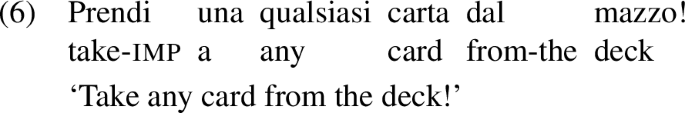

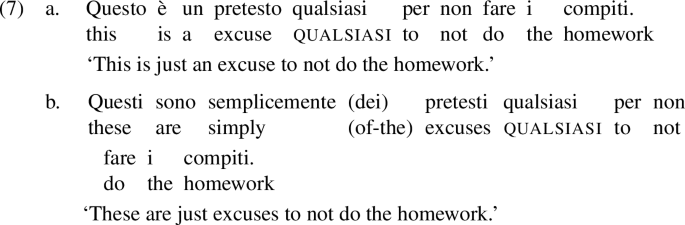

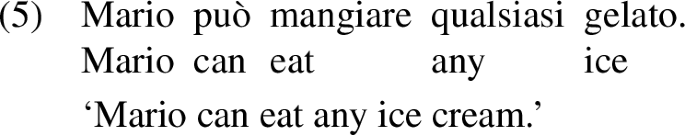

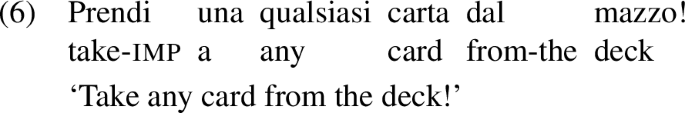

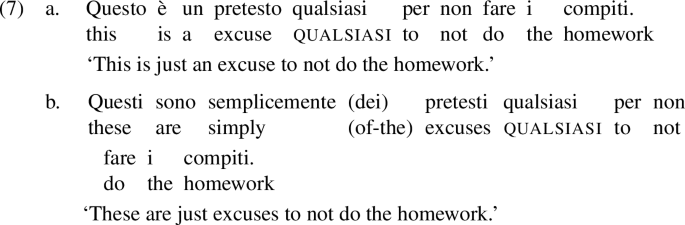

The following remarks should be taken into consideration. In the case of M.I.DIA. the year was not provided and only an alphanumeric string for the source was available. We established the year by first determining the original source in the corpus’s documentation and then finding the corresponding year of publication. If only a period of time was available, a random year within the latter was chosen. Second, syntax and type of text were labelled only when linguistically relevant (e.g. archaism, jargon, …). Besides its standard determiner position, qualsiasi can also combine with the indefinite article un and can occur in a post-nominal position with an adjective-like behaviour:

-

1.

plain qualsiasi:

qualsiasi precedes the noun and is not combined with an article, as in (5):

-

2.

un qualsiasi NP:

qualsiasi precedes the noun and is combined with an indefinite article (i.e. un[o/a]), as in (6):

-

3.

post-nominal qualsiasi:

qualsiasi precedes the noun and might be combined with an indefinite article, as in (7a), or not, as in (7b):

Accordingly, for each example we specified its form and we further classified it in some relevant categories. The latter were based on Haspelmath (1997) together with some functions introduced in Aguilar-Guevara et al. (2011) and a few introduced in the present work.

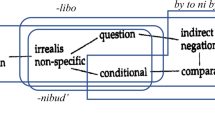

Haspelmath was the first to use a semantic map to organize the main functions of indefinites. A semantic map is a tool for a cross-linguistic visualization of linguistic expressions, which share some semantic/functional features (e.g. morphemes, constructions, concepts). The functions are organized in an implicational way: a certain item always expresses functions which are contiguous (i.e. connected by a line) on the map. An extended semantic map given by Aguilar-Guevara et al. (2011) is represented in Fig. 2, where the boldface labels indicate the new functions introduced by Aguilar-Guevara et al. (2011).Footnote 17

Aguilar-Guevara et al.’s (2011) semantic map

Besides the functions in the figure above, several off-map functions were introduced to deal with all the occurrences of qualsiasi. In certain cases, our item did not behave as an indefinite and therefore new labels for classifying all the examples were needed.

The first off-map function is the Indiscriminacy function (ind), which comes from Horn (2005) and is exemplified in (8). ind is usually existential and it gives an average and sometimes pejorative flavour to the noun it is associated with.

Another important off-map function is the no matter one, introduced by Aguilar-Guevara et al. (2011), which roughly corresponds to an English ‘whatever’ construction without strictly behaving as an indefinite. An example is provided in (9):

The labels of the functions are summarized in Table 3. The functions from a. to h. were taken from Haspelmath (1997); i. to n. from Aguilar-Guevara et al. (2011); o. and p. were introduced to label all the examples in our database.Footnote 18 As regards the annotation phase, we followed the procedure described in Aguilar-Guevara et al. (2011). If an example was unclear between two readings, we randomly assigned a function between the two. In the case the available readings were greater than two, we labelled the example as unclear.

3.2 Distribution

The total number of occurrences and labelled examples is reported in Table 4.

Figure 3 shows the temporal distribution of the item qualsiasi for the occurrences found in our corpora.

Crucially, we obtained the above temporal distribution only after the annotation phase, since the year was usually not provided, as explained in Sect. 3.1. In the chart, we made divisions of 28 years, corresponding to half of each 56-years period we considered (see Sect. 4.1). We observe an unusual peak in the years 1911–1938. There might be two reasons for this finding. First, two corpora (M.I.DIA. and LIS) were both considered in this time span, leading to an increase in the number of examples. Second, we might suppose that in these years the texts available were more numerous, given the intuitive fact that the more we go back in the past, the fewer resources we have. Therefore, we decided to consider only a random selection of 60% examples between 1911–1938. As a consequence, the whole period 1911–1967 presented a more uniform temporal distribution, which is important for a correct evaluation of the diachronic development of our functions. It might be possible that other peaks could be found by looking at shorter intervals of time. In this case, however, we believe that significant language changes cannot occur if the period is not sufficiently extensive and therefore a non-uniform distribution should not be problematic.

We also observe that in the interval 1883–1910, the post-nominal form showed a significant presence, compared to the pre-nominal one. We do not have an explanation for this fact and we decided to consider all the data. A hypothesis, by looking at the examples, is that this form was used for stylistic purposes in formal writing, but the data we considered is not sufficient to draw any clear conclusion.

The distribution of qualsisia and qual si sia is depicted in Fig. 4.

We observe a peak in the 1300s in the case of qual si sia. This is due to the presence of the OVI corpus, which covers only periods before the 14th century. If only M.I.DIA. had been considered, the number of occurrences in the 1300s and 1400s would have been somewhat similar. Furthermore, the chart shows that these forms essentially disappeared after the 1800s, in line with the predominant diffusion of qualsiasi.

4 Results

In this section, we gather the results obtained in the corpus study following the subdivisions introduced before. The database containing all the examples is available in Comma-separated values format at the following link: https://osf.io/an4hz/, (last accessed 20 May 2021).

Our main finding is a link between the no matter function and early uses of our item. This relationship was not directly observed in the case of qualsiasi. However, in the proclitic form qualsisia, the no matter function was the most prevalent. Furthermore, the original expression qual si sia displayed a great prevalence of no matter uses before stages of qual si sia with a fc meaning. As we will see in Sect. 5, our results will be particularly useful to reconstruct the emergence of the fc indefinite qual si sia and its related forms.

In Sect. 4.1, we outline the results for qualsiasi in its plain form and in combination with un. As said, even if our data do not display a clear relationship with no matter at this stage, a diachronic examination of qualsiasi’s functions is important, given the change in frequency observed in Fig. 1, as we point out in Sect. 4.2. The results for qualsisia and qual si sia are described in Sect. 4.3 and 4.4 respectively. Given the importance of the early data, we first present here the results of our annotation. Then, we dedicate Sect. 5 to a thorough examination of the early uses of qual si sia.

4.1 qualsiasi

The item qualsiasi comprised a total of 474 examples, divided in the forms in Table 5.

Before the end of the 18th century, only 3 occurrences were found in our database (1600 – ufc; 1639 – ufc; 1703 – no matter). Starting from the year 1797 we divided our data in 4 periods of 56 years. Since our database comprised different corpora and resources, the examples needed to be uniformly distributed to obtain a coherent interpretation of the results, as explained in Sect. 3.2.

We will now present the detailed results of the annotated functions for all the forms we considered.

4.1.1 Plain qualsiasi

From a synchronic point of view, the resulting Haspelmath map is depicted in Fig. 5, which was obtained by considering only the examples for qualsiasi in the last century.

An important remark concerns the presence of dn (direct negation)Footnote 19 and aa (anti-additive) functions.Footnote 20 These examples were few and we note that these environments normally host negative polarity items (npis). A possible explanation might be that a significant number of items in many languages share fc and np uses, and qualsiasi expresses this symmetry in these borderline cases.

Let us now look at the diachronic data following the divisions introduced before.

The charts seem to offer no clear conclusion with regard to the grammaticalization of qualsiasi as an indefinite, since the first occurrence which we found was already an indefinite with ufc function. Furthermore, qualsiasi does not display great variation through the periods considered in Fig. 6. In this regard, we attribute the greater variety of functions in periods (b) and (c) to the larger number of occurrences in our database, rather than to an enlargement of the semantic map of qualsiasi.

Lastly we note that the no matter function occurred with less frequency in the last two periods compared to the first two ones. The data we considered is not sufficient to conclude any statistically significant result, but this tendency should be noted in light of the impact of the no matter function in the development of indefinite uses of qualsiasi from qual si sia, as we will shortly see. Before that, let us briefly look at the case of un qualsiasi and post-nominal qualsiasi.

4.1.2 un qualsiasi NP

Synchronically, we obtained the Haspelmath map in Fig. 7 for this form, where the functions in bold were not found in the database, but considered relevant by native speakers:

Diachronically, the distribution of the functions is reported in Fig. 8. It shows that the two main functions for the form un qualsiasi NP were fc and ind. In particular, with the exception of the last period considered, the fc function displayed a slight prevalence overall.

4.1.3 post-nominal qualsiasi

For the post-nominal case, the Haspelmath map is shown in Fig. 9.

Diachronically, the same considerations of the form un qualsiasi NP seem to apply (see Fig. 10). We note, however, that in this case we observe a prevalence of the ind function over the fc one.Footnote 21

4.2 Interim conclusion

We have examined the diachronic distribution of qualsiasi and its combination with the indefinite article un between the end of the 1700s and the year 2019. We have observed no clear changes in their functional distribution. Even if the data does not show any clear pattern, these results provide an answer to one of the motivating questions of our diachronic study. In Sect. 2.2 we noted that starting from the mid of 1900s qualsiasi became the most widespread indefinite in the Italian language. The charts in Fig. 6 show that this change in frequency did not have a significant impact on the distribution of the functions of our indefinite, contrary to what one might have expected.

We also note that based on our data the form un + qualsiasi is only available starting from the mid-1800s. Crucially, this seems to coincide with the rising diffusion of qualsiasi (see frequency graph in Fig. 1). We conjecture that once qualsiasi started to become more common and somehow recognized as an indefinite determiner by the grammar, the combination with un became available by mirroring the behaviour of other fc indefinites (e.g. un qualunque).Footnote 22

We will now proceed to outline the results for the proclitic form qualsiasi and the whole expression qual si sia.

4.3 qualsisia

The first occurrence of qualsisia in our database dates back to the year 1586 and the presence of qualsisia is predominant in the 17th century, with just one example in the 18th (175–co) and only few in the 19th (1800–dn; 1827–gen; 1836–ufc; 1870–ind). As regards the form un qualsisia NP, two examples were found and they both occurred in 1620 with the ind function. The post-nominal form was not observed.

Let us now focus on the period 1586–1699. A total of 13 occurrences were found with the distribution in Fig. 11.

As shown in Fig. 11, the predominate function is no matter. This is in clear contrast with the results of qualsiasi, where the no matter function was never the most prevalent. As a result, we hypothesize that qualsisia originated from no matter uses, and then acquired an indefinite status by a process of grammaticalization. However, even in this case, qualsisia is already used as an indefinite since its first occurrences. To support our claim, we will proceed with an analysis of qual si sia, the expression from which qualsisia was formed by a morphological process of compounding.

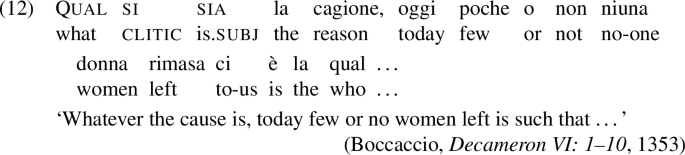

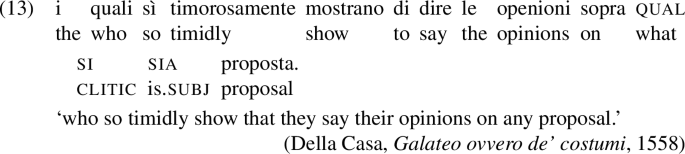

4.4 qual si sia

Our database included a total of 55 examples temporally distributed between the 14th century and the 17th one. We divided our data in periods of one century each. With particular regard to the functions of this expression, the results are summarized in Fig. 12, where the wh-embedded label was used for indirect interrogative clauses like (2).

The charts clearly show that the no matter function is predominant in early uses of qual si sia and only in a later stage indefinite uses were possible. This might support our hypothesis that fc originated from no matter uses. We will dedicate the next section to this conclusion and to its implications for semantic theories of fc. Moreover, we will also analyze the data by taking into consideration the different configurations of the no matter function. As we will see, this will enable us to reconstruct the emergence of fc uses of qualsiasi.

5 The emergence of FC qual si sia

In this section, we will try to reconstruct how qual si sia developed into a fc item. As Fig. 12 shows, in our diachronic study we found three main different constructions in which qual si sia appeared:

-

1.

Embedded wh-clause:

-

2.

No matter:

-

3.

FC indefinite:

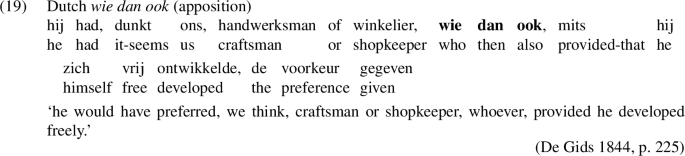

Moreover, after the first no matter uses, qual si sia started to also appear between two commas both before and after the relevant noun, as in (14a) and (14b) respectively. The associated reading was still no matter, but the nominal expression present in standard no matter cases was omitted. We analyze this kind of parenthetical constructions as appositions:

In the following section, we will delineate a more accurate description of each construction (wh-embedded, no matter, apposition), illustrating how qual si sia finally developed into a fc indefinite.

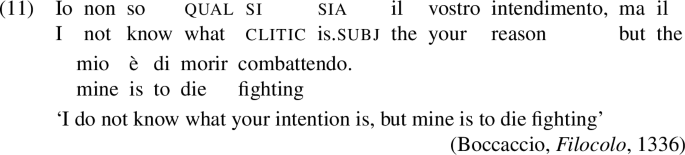

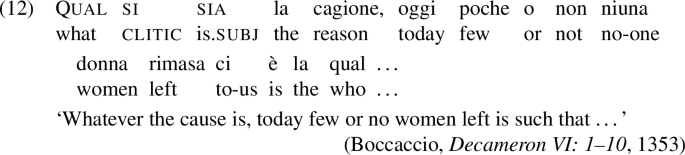

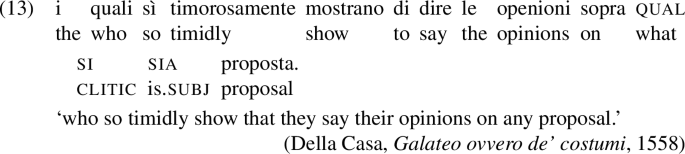

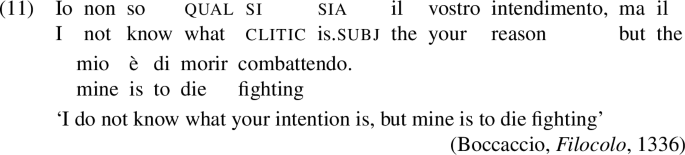

5.1 Wh-embedded clause

As noted in Sect. 2.2, qual(e) is an interrogative word and its natural environments are direct or indirect interrogative structures. The number of examples with the specific combination qual si sia were quite limited. After all, we are considering a very specific ‘indefinite plus clitic’ construction with subjunctive mood. In our database all examples were indirect interrogative questions with the verb to know in a negated form, which normally triggers subjunctive mood, as in the example (11) repeated below. We note that this usage of qual(e) survived in current Italian, even though the presence of the particle si, in this kind of indirect interrogatives, is no longer possible.

5.2 Unconditional

We will now turn our attention to what we have called no matter uses of qual si sia. Let us look at an example from the 15th century given in (15a) and a similar example in current Italian in (15b).

In the literature these kind of constructions are usually called (parametric) concessives (Haspelmath and König 1998; Gawron 2001) or (constituent) unconditionals (Zaefferer 1990; Rawlins 2008a, 2013). In the following sections, we will use the term unconditionals.

It is important to point out some remarks about the structure of the Italian construction in (15a). First, the adjunct is formed by a wh-element and the verb to be in subjunctive mood. Second, the use of the particle si, as noted in Sect. 2.2, is used here as an intensifier. Third, the clause which follows the adjunct has an inherent modal flavour. In the case of (15a), the latter amounts to the conditional mood of vorremo. Lastly, we note that the construction in (15a) is no longer possible, and the indefinite qualsiasi is now required, as in (15b).

In general, we observe that the meaning of an unconditional resembles very closely the free choice reading typically associated with qualsiasi. It might not be unreasonable to regard this particular construction as the origin of fc in the case of qualsiasi. In Sect. 6, we will see how this idea might be implemented in a specific semantic framework. Before that, let us concentrate on another subtype of no matter uses: appositional constructions.

5.3 Apposition

In our database we found an additional configuration, where qual si sia occurred alone between two commas, as in (14). The latter started to appear after the first no matter uses, and for a certain period of time, it was used concurrently with plain no matter cases. After the development of the full fc indefinite, no examples were found in the corpora we examined. In this kind of construction, our item covertly refers to a DP in the main clause. For instance, in the case of (14b), we would have something along the lines of (16):

The presence of the two commas suggests that the expression qual si sia in (16) might be considered an appositional construction, interpreted at a different level than the main clause. To see this, consider the toy example in (17):

For a nominal apposition like (17), Potts (2005) argues that the content of the main clause is at-issue, while the one expressed by the appositional construction is non at-issue and it is computed by a specific comma operator.Footnote 23 In a similar way, we claim that the appositional stage of qual si sia is interpreted at a different level than the main clause. The resulting non at-issue content, in this case, has a no-matter meaning similar to the unconditional case we discussed before:

For a sentence like (18a), the at-issue content in (18b) expresses the fact that there is a letter on the table, while the non at-issue content in (18c) conveys that it does not matter which particular letter is on the table. We would like to underline that the contribution of qual si sia is considered to be non at-issue because, broadly speaking, it is not the main point of the utterance. A common diagnostic for determining the (non) at-issue content of an utterance is by analyzing a possible assent/dissent continuation. In the case of (18a), if the addressee continues with ‘Yes, that’s true’ or with ‘No, that’s not true,’ she wants to claim that the letter is or is not on the table, but her assent or dissent does not concern the meaning expressed in (18c).Footnote 24 It is the contribution of the apposition qual si sia which gives rise to the non at-issue content in (18c), signalling that it does not matter which letter is on the table. In particular, a possible way to capture such enriched meaning would be to analyze the apposition as a hidden unconditional clause of the form ‘qual si sia the letter, it is in on the table,’ with the second part elided, along the lines of (16).

In our database, the first occurrences of qual si sia in an unconditional construction are temporally located in the early/middle 13th century. After approximately half a century (late 13th century), appositional constructions started to emerge.Footnote 25 A natural question, in this regard, is why speakers started to express the no matter function with an appositional construction and not with a full unconditional structure. We might conjecture that, when the use of qual si sia as an unconditional became more widespread and typical, ease of communication induced speakers to use a more concise formulation to express the same claim.

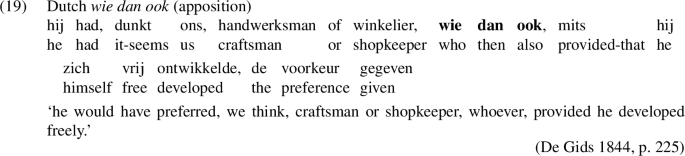

We suppose that this appositional construction acted as an intermediate configuration between standard no matter and indefinite uses, and facilitated the integration of the fc meaning at the nominal level.Footnote 26 Indeed, we conjecture that it is here that the generalizing reading of no matter constructions got reinterpreted in the meaning of the indefinite. In this regard, we note that a similar construction can be found in the emergence of the Dutch free choice item wie dan ook (see Aguilar-Guevara et al. 2011; de Vos 2010).Footnote 27As a result, our hypothesis that the Italian qual si sia went through such a stage, besides being empirically attested, is also supported by other grammaticalized fc indefinites.

5.4 Free choice indefinite

Two centuries after the first no matter uses, qual si sia started to be used as a fc indefinite. Structurally, we observe that the first form was qual si sia. After a competition period between the proclitic form qualsisia and the enclitic one qualsiasi, only the latter survived. As already noted, while the plural form qualsisiano was originally possible, the plural form was no longer available when qualsiasi became fully integrated in the grammar.

We end this section with an important remark concerning the co-occurrence of qual si sia with a series of disjunctions. The examples in (20a) and (20b) are two relevant representatives:

Our data does not show that this construction is crucial in the development of qual si sia, since these examples occur after the first fc uses, and similar cases are also possible in current Italian with the full indefinite qualsiasi. However, we note that a similar parallelism between disjunction and free choice can be found in the development of other indefinites. The example in (21), from the corpus study of Aguilar-Guevara et al. (2011), illustrates the case of the Dutch wie dan ook and the one in (22), from the work of Company Company (2016), the Spanish cualquier(a):

This kind of disjunctive construction might have constituted an intermediate context where fc got consolidated: any of the people or objects the indefinite stands for would be sufficient to satisfy the purposes the speakers are considering as a possible disjunct.

We observe that the example in (20a), as well as the Dutch case in (21), seems closer to the appositional construction we examined before, with an additional prepositional phrase triggering the apposition. By contrast, in the example in (20b) and in the Spanish one in (22) our items associate with a noun. It might also be possible that this environment facilitated the development of an indefinite determiner status of qual si sia from an appositional stage, where it was computed at a different content level, to a position outside the appositional boundaries and directly computed in the matrix clause.Footnote 28

6 Semantic analyses of FC

In this section we will examine how our diachronic data is compatible with current semantic analyses of fc. We will first start with some desiderata which any semantic theory of fc should account for. Then, we will take into consideration two different semantic frameworks: Alternative Semantics accounts for indefinites (e.g. Kratzer and Shimoyama 2002) and grammatical approaches to implicatures (e.g. Chierchia 2013). By doing so, we will try to illustrate how our diachronic investigation might shed some light on these analyses. Given the purposes of this paper, we will not focus on the technical details behind these semantic analyses. Instead, we hope that the non-initiated reader will be able to grasp the main building blocks of these accounts and thus better appreciate the role that diachronic data might have in evaluating these theories.

Semantic analyses of fc should be able to account for three main facts. First, as outlined in the introduction, indefinites display a great quantificational and functional variability. A proper account of fc should be embedded within a general theory of indefinites which explains their differences. Second, fc indefinites display a clear universal character, even if they cannot be considered universal quantifiers (see Menéndez-Benito 2010). Lastly, fc items are usually associated with a particular restricted distribution.Footnote 29 For instance, they are normally infelicitous in episodic statements, but fine under possibility modals. To see this, consider the contrast below. While (23a) is ungrammatical, a similar construction with the modal can in (23b) is fine:

One of the main challenges of semantic theories of fc is to arrive to an account of the universal meaning of fc indefinites which also explains their restricted distribution.

6.1 Alternative semantics accounts of indefinites

6.1.1 Outline

Alternative Semantics has its roots in Hamblin (1973), who proposed an extension of the basic type-theoretic framework commonly used in formal semantics in order to provide an account of questions. In Alternative Semantics, the meaning of a sentence is not captured by a single proposition, but rather by a set of propositions (a set of alternatives). Within the framework of Alternative Semantics, Kratzer and Shimoyama (2002) present an elegant account of the variety of indefinite forms: their common core is their potential to induce a set of propositional alternatives and their differences derive from their necessary association with different operations of propositional quantification.Footnote 30

More formally, in this alternative based account all expressions denote sets. Most lexical items denote singleton sets, while indefinites and wh-phrases denote (multi-membered) sets of individual alternatives. The generated alternatives keep expanding by point-wise functional application to create propositional alternatives.Footnote 31, Footnote 32 For instance, in the case of (24a), the corresponding set of propositions will be:

These alternatives keep growing until they are closed by an operator, responsible for their quantificational force. Adapting from Kratzer and Shimoyama (2002), we consider the following operators:

As stated, this is how Alternative Semantics analyses based on Kratzer and Shimoyama (2002) capture the quantificational variability between indefinite expressions: different indefinites can associate with different operators, while their core semantic meaning is their alternative-inducing behaviour. Following Menéndez-Benito (2005), Aloni (2007), we assume that the quantificational force of the alternatives generated by fc items is given by the [∀] operator, which instructs all alternatives to be true.

In addition, as originally showed by Menéndez-Benito (2005), these alternatives need to be mutually exclusive with each other.Footnote 33 In the following, we will indicate this mutual exclusiveness with an operation of propositional exhaustification and we will indicate the latter with exh. We also assume that exhaustification leads to a logical partition, as in the representation between brackets in (26c). In practice, some of these exhaustified alternatives are often eliminated due to some existential or uniqueness presuppositions.Footnote 34 Exhaustification also explains why a plain episodic statement like (24a) gives rise to a contradiction and it is normally considered infelicitous:

By contrast, the intervention of a possibility modal like can rescues the alternatives from contradictions. The resulting reading is the desired one, where each alternative is possibly true:

We note that the Alternative Semantics framework presented here can be generalized to account for subtrigging configurations (Aloni 2007), for intervention effects (Kratzer 2005), for indefinites in comparatives (Aloni and Roelofsen 2014), and it has also been empirically successful in describing the meaning of fc indefinites in a variety of languages.Footnote 35

One fundamental question which remains unexplained is why, in principle, fc indefinites need to associate with a [∀] universal operator and why they generate exhaustive alternatives. In the next section, we will see how diachronic data might provide an answer to these issues.

6.1.2 Wh-embedded clauses

As stated, in the alternative based account outlined before wh-words and indefinites both give rise to sets of alternatives. This assumption is compatible with our data. As we noted, qual is an interrogative word and the first uses of qual si sia were indirect interrogative clauses, like the one we encountered in (11).Footnote 36 Indirect interrogative clauses can be easily implemented in alternative semantics frameworks by means of specific propositional attitude operators:Footnote 37

In (28), we adopt the formalization of Aloni (2007, ex. (38)-(39)), which models know as a combination of believe and a \([\textsc{true}]\) operator.Footnote 38 In particular, the indefinite qual generates a set of alternatives which combine with the verb sia and with its predicative complement your intention.Footnote 39 After exhaustification,Footnote 40 these alternatives are selected by [Q] which avoids existential closure, which would otherwise occur as default, and signals that we are dealing with a question. The \([\textsc{true}]\) operator selects the unique true exhaustive proposition (i.e. the true answer) in the set of alternatives, capturing the factive aspect of knowledge verbs. The resulting reading is the desired one: it is not the case that the agent believes the unique true answer to the question ‘what is your intention?’.

Setting aside the specific implementation of indirect interrogative clauses, we note that at this stage the wh-element qual is simply associated with [Q] and does not display any particular integration with si sia.

6.1.3 Unconditionals

We have already noted that the free choice meaning of fc indefinites resembles very closely the generalizing reading typical of unconditionals. In this section, we will show how this latter reading is implemented in Alternative Semantics accounts of unconditionals and how this might be related to fc indefinites.Footnote 41

For ease of readability, we will now work with the toy example in (29) and then we will point out the particularities of the Italian case.

Since the first studies on unconditionals (see e.g. König 1986),Footnote 42 a strong parallelism between standard ‘if’ clauses and unconditionals has been noted. The underlying idea is that an unconditional expresses a set of conditional claims. However, unlike canonical ‘if’ clauses, unconditionals often display the following crucial features:

-

(a)

they are associated with an ‘indifference’ flavour (i.e. in (29) it does not matter which gift is);

-

(b)

the main sentence of an unconditional is entailed by the whole construction. By contrast, a standard ‘if’-clause expresses a claim that holds only if the conditional antecedent is satisfied.

Intuitively, unconditionals involve some sort of universal quantification over epistemic alternatives, as several analyses of ‘whatever’ constructions usually assume (see e.g. Dayal 1997; von Fintel 2000). Indeed, while the conditional adjunct of standard ‘if’-clauses can be bound by a variety of operators which can determine their quantificational force (Lewis 1975; Kratzer 1986), unconditionals seem to prefer operators with a quasi-universal or generic meaning (e.g. adverbs like always or almost, but not sometimes or once).Footnote 43 According to Rawlins (2008b,a) unconditionals adjuncts should be treated as interrogative structures,Footnote 44 leading to the emergence of exhaustified alternatives in the same spirit of the Alternative Semantics framework introduced above. As a result, a sentence like (29) is really a set of conditional claims:Footnote 45

In (30), ⇒ stands for a conditional operator which takes the content of the conditional adjunct and based on the latter it restricts the domain of its scope (i.e. the consequent ‘I will be happy’).Footnote 46 Due to the inherent universal character of unconditionals, each alternative acts as a restrictor on the main clause. This can be captured by a universal operator [∀] which puts together the set of conditionalized propositions by instructing that all of them are true.Footnote 47

Since the alternatives in (30) denote a partition of the logical space, the main clause is entailed, as we should expect in this kind of unconditional construction. Moreover, this analysis accounts for the ‘indifference’ flavour of no matter constructions, since all the alternatives act as a restrictor to the main clause, leading to the interpretation that ‘it does not matter which gift is, I will be happy anyways’. Furthermore, the presence of the English adverb ever widens the domain of individuals under consideration, strengthening the generalizing or indifference reading outlined above.Footnote 48 In the Italian case qual si sia,Footnote 49 there is no ‘ever’ equivalent. However, we note that here the alternatives generated by the wh-element qual combine with the ontologically most general and neutral verb (to be) with an intensifier particle (si) and in subjective mood, which is an irrealis mood conveying open possibility. Based on these considerations, we can also understand why this particular verbal form together with qual ultimately grammaticalized in a free choice indefinite.Footnote 50

It is important to note that in (30), qual, together with si sia, is still associated with a [Q] operator, given the interrogative nature of unconditional adjuncts. Then a universal operator [∀] applies on top of the conditionalized alternatives. By contrast, in the case of fc indefinites, as in (27a), [Q] is not present anymore and the alternatives are directly associated with [∀].

6.1.4 Conclusion

Let us now recap what we have discussed so far. In an Alternative Semantics account, unconditionals are a set of conditionalized propositional alternatives bounded by a universal [∀] operator. A free choice indefinite was analyzed as a set of exhaustified propositional alternatives which were conventionally associated with the [∀] operator. Based on our analysis, the diachronic development of qual si sia, and consequently its compound form qualsiasi, can be described as follows:

-

(i)

wh-embedded clause

-

a.

I do not know qual si sia your intention.

-

b.

\(\neg Bel_{I} \ [\textsc{true}] \ [Q] \ (\textbf{exh} \text{(qual(si), is your intention))}\)

-

a.

-

(ii)

unconditional

-

a.

Qual si sia the gift, I will be happy.

-

b.

[∀] ([Q] exh (qual (si), is the gift)⇒I will be happy)

-

a.

-

(iii)

fc indefinite

-

a.

Qual si sia person can sing.

-

b.

[∀](◊((exh(((qual si sia, person), sing)))))

-

a.

In step (i), the alternatives are introduced by the bare wh-indefinite qual. These alternatives associate with [Q] to avoid existential closure, and with an operator of exhaustification. The unconditional stage in step (ii) still involves an interrogative construction in the adjunct of the unconditional. As explained before, due to a conditional operator, this set of alternatives acts as a restrictor on the main clause. On top of these, a universal operator [∀] puts together the set of conditionalized alternatives and makes all of them true, leading to the desired reading. In stage (iii), the alternatives are generated directly by the fc indefinite qual si sia, which is conventionally associated with a universal [∀] operator and the exhaustification operator exh.

Appositional construction, which might be analyzed as unconditionals expressed at a different content level, might have facilitated the change from step (ii) to step (iii), as we said earlier,Footnote 51 by acting as a bridging phase between unconditional uses and the determiner status of qualsiasi. The Italian unconditional structure which we have examined has an inherent universal force and an exhaustive interpretation. By adopting an appositional construction, speakers started to associate the whole unconditional construction with the expression qual si sia. Then, qual si sia escaped the appositional boundaries, and completed its grammaticalization process.

Based on these diachronic considerations, it is reasonable to assume that the fc indefinite qualsiasi is conventionally associated with a universal propositional operator and with an exhaustive interpretation.

If this analysis is correct, it would predict that fc indefinites need to acquire their universality from a stage of language with a clear universal interpretation.Footnote 52 In this regard, Aloni (2017) showed that similar stages can be found for the case of the Spanish cualquier(a), which emerged from a universally read free relative construction, and the Dutch wie dan ook, which was initially associated with an unconditional construction similar to the one examined in the present work.

It might be possible that other languages do not display an early stage which motivates the need of a universal operator. Such language would constitute a counterexample to our generalization, since the meaning of fc could not be derived from an alleged universal operator. An example might be the case of the German irgendein, which comes from a locative particle and did not display a clear universal stage in its development (see Jäger 2008; Port and Aloni 2015). Crucially, Alternative Semantics analyses of irgendein (e.g. Kratzer and Shimoyama 2002) associate the latter with an [∃] operator and derive its fc meaning by a pragmatic inference due to domain widening. On the one hand, this shows that our [∀]-prediction is potentially falsifiable based on the different diachronic developments of fc indefinites. On the other hand, the possibility to account for different diachronic paths by offering a pluralistic treatment of fc indefinites which is tied to their diachronic development is what makes the Alternative Semantics approach particularly attractive.

Lastly, we note that our account fits very well with recent observations made by Beck (2017, 2020) about the diachronic semantic development of universal quantifiers.Footnote 53 According to Beck (2017), based on previous observations by Haspelmath (1997), universal quantifiers might emerge from so-called free choice relative clauses. The latter are analyzed in an alternative based account similar to our treatment of unconditionals outlined before (i.e. universal quantification over propositions). Crucially, Haspelmath (1997) also notes that some fc indefinites themselves might become universal quantifiers. This means that our account, together with Beck’s (2017) line of research, might be also helpful to understand how universal quantification over alternative propositions, as in fc indefinites, might then change to overt universal quantification of individuals, as in universal quantifiers.

We will now turn our attention to a different and widely adopted account of fc: the grammatical approach developed by Chierchia (2006, 2013). In the following section, we will focus on the account put forward by Chierchia (2013). As done with the Alternative Semantics account, we will explain how Chierchia’s (2013) framework deals with the tree desiderata mentioned at the beginning of Sect. 6. After a brief outline, we will argue that this analysis is less compatible with the diachronic data presented in this article.

6.2 Free choice in the grammatical approach

6.2.1 Outline

In an influential approach Chierchia (2013) treats indefinites as plain existential expressions. Marked indefinites (indefinites with a restricted distribution or polarity items) are assumed to obligatorily activate alternatives. Active alternatives require the application of an operation of exhaustification (Fox 2007). The difference between indefinites is then accounted in terms of variation of the type of alternatives they may activate and the mode of exhaustification they employ. Universal fc indefinites, like any or qualsiasi, activate so-called domain alternatives and scalar alternatives, and they allow for recursive exhaustification, leading to a universal-like (free choice) inference.

We observe that in this way Chierchia (2013) is able to capture the quantificational variability between different indefinites, as well as the universal character of fc indefinites. The latter are indeed the first two desiderata mentioned at the beginning of Sect. 6. In combination with other assumptions (wide-scope constraint and modal containment), which we explain below, Chierchia (2013) is also able to account for the restricted distribution of fc indefinites.

Let us thus consider how Chierchia (2013) derives fc and why the latter inference does not arise with episodic statements, which we know to be ungrammatical. For the purposes of this section, we will consider the case of any, but the same analysis can be generalized to qualsiasi:

We will work with a minimal toy model with two individuals in the domain. For a sentence like (31), Chierchia (2013) assumes the presence of two domains of alternatives: one generated by standard subdomain of alternatives and the other one by scalar reasoning. For readability, we will abbreviate H(a) & S(a) with A and H(a) & ¬S(a) with ¬A. Similarly for b:

The episodic sentence in (31) is represented as in (33a), where any is analyzed as an existential. The fc and scalar implicatures arise by exhaustifying with respect to the respective domains of alternatives introduced in (32).

We see that in the case of episodic sentences like (31), a clash between fc and scalar implicatures occurs, resulting in a contradiction and therefore ungrammaticality. Chierchia (2013) needs to explain why this contradiction does not arise in the case of possibility modals, as seen in (23). In order to do so, Chierchia (2013) assumes the following two constraints:Footnote 54

The first constraint is syntactic and tells us that in modal sentences the fc item any takes scope over the modal. As a result, the only admitted logical form for a sentence like (36a) is (36b):

The second constraint regards the modal bases associated with the implicatures (i.e. the set of worlds over which implicatures quantify). Chierchia (2013) argues that scalar implicatures have a smaller set than free choice ones, being SC compatible with what he calls the ‘privative’ evidential source of the speaker and FC with the intersubjective evidence of discourse participants.Footnote 55

The logical representation for a sentence like (36a) given WSC and the derivations above is the following, where w stands for the world of interpretation:

It seems that the clash between (37a) and (37b) is the same, but here MC comes into play. Since FC ⊂ SC, the implicatures can be true in different worlds given an appropriate model of interpretation.

6.2.2 A diachronic perspective

The grammatical approach presented here faces some incompatibilities with our diachronic study. First, in the Alternative Semantics case, the link between interrogative uses of qual and the fc treatment of qualsiasi is evident, since they both give rise to sets of alternatives. In the grammatical approach, there seems to be no clear connection between questions and indefinites.Footnote 56

Second, the different operators posited by Alternative Semantics accounts find a natural explanation in the semantic characterization of unconditionals. In that case, the association of the fc indefinite qualsiasi with a universal operator and with an exhaustive reading appears to be inherited by previous uses of the indefinite morphology. By contrast, the grammatical approach leaves an important issue open: why the implicature generated by fc indefinites is part of the grammar (by means of specific exhaustification operators) and what motivates its non-defeasability. In a recent work, Szabolcsi (2019) extended the grammatical approach to the analysis of unconditionals. In this framework, unconditionals are treated as existential statements which undergo recursive exhaustification. To avoid contradictions of the kind outlined before, Szabolcsi (2019) assumes the presence of a covert modal operator in the main clause of the unconditional. Setting aside the technical issues of this work, we note that this account does not fully explain why, in principle, unconditionals were associated with an obligatory (grammatical) implicature. It seems that all we can get here is a circular answer, where the central question, why fc is derived in the grammar, remains unsolved.

This does not mean the grammatical approach is necessarily wrong. One may argue that there is a general underlying principle of language which makes both unconditionals and fc items compatible with a specific kind of (recursive) exhaustification. Indeed, one of the aims of Szabolcsi (2019) is to provide a theory which brings together free choice, (negative polarity items) and unconditionals. However, this account assumes that unconditionals are themselves triggered by wh-items which independently exhibit universal fc uses (e.g. the Hungarian akárki in the case of Szabolcsi 2019). By contrast, our diachronic data showed that the unconditional structure from which qualsiasi developed was formed by the plain wh-element qual(e), which has no dedicated universal fc uses.Footnote 57

As a result, while the grammatical approach is able to bring under the same umbrella different otherwise puzzling phenomena associated with fc, it does not explain, based on our diachronic data, how to make sense of the grammaticalization of Italian fc from the plain indefinite qual(e) to the fc one qualsiasi.

7 Conclusion: Free choice and diachronic adequacy

In this work, we have examined the diachronic evolution of the fc Italian indefinite qualsiasi. Based on the collected data, we were able to reconstruct its grammaticalization path from its origin to its uses as an indefinite. We have noted that the fc reading of qualsiasi might be inherited from the generalizing reading of unconditional constructions, in which our item appeared before starting to be used as an indefinite. We have then outlined an analysis of fc based on the framework of Alternative Semantics, and we have explained how our diachronic data might be interpreted and accounted for within this analysis. By contrast, one of the main competing theories of fc, the grammatical approach, gave no principled answer to the diachronic data, which seemed hardly compatible with this account.

It is commonly assumed that semantic theories should be able to account for the empirical data of the phenomena under investigation. Usually, this is only measured at a synchronic level by means of consistency with native speakers’ grammatical intuitions. Recent development in linguistic theories taught us how important data collection of speakers’ judgements is. Similarly, the linguistic community started to recognize the value and relevance of experimental methods in assessing their theories and predictions.

In the same spirit, we believe that the empirical adequacy of semantic theories should not only be examined from a synchronic viewpoint, but diachronic considerations should have a role as well. Language involves intrinsic dynamic processes and a proper understanding of our present relies on a proper understanding of our past. On the one hand, semantic theories should be able to determine what the contribution of a certain functional expression is. On the other hand, they also need to take into consideration how that phenomenon emerged in the historical processes which ultimately constitute the basis of the current synchronic picture of language.

Notes

Evidence of this comes from the fact that their recent grammaticalization can still be witnessed in the indefinites themselves.

See however Company Company (2016), Company Company and Loyo (2006), which contain some interesting data regarding the Spanish fc indefinite cualquier(a). See also Gianollo (2019) for a valuable work on indefinite pronouns and determiners between Latin and Romance, even tough it touches only marginally fc ones.

A salient feature of fc indefinites is their fairly stable cross-linguistic distribution. For instance, they are allowed in possibility statements, but they are often disallowed in episodic contexts. See Dayal (2004) for an overview.

We are aware (see James and Weiss 2012) that Google Ngram Viewer has been largely criticized for poor OCR and incorrect metadata, such as the year of publication. This might have a huge impact on the interpretation of the results. However, given the large number of texts available after the 18th century, we suppose that some general considerations regarding the distribution of the Italian vocabulary can still be made. From a diachronic point of view, instead, Google Ngram Viewer cannot be considered a valuable resource. Indeed, we found several instances of qualsiasi before the 1800s, but the corresponding year was incorrect with an error of at least one century.

See e.g. Bybee 2015, ch. 9.

The example we are considering in this preliminary section occurred after the fc uses of qual si sia. However, as we will see in our diachronic study, the first occurrences of the expression qual si sia were indeed indirect interrogative structures.

It is interesting to note that, to our knowledge, this particular use of si is not discussed in the literature (e.g. Cinque 1988). Indeed, in current Italian a sentence like (2) is quite odd, but it is acceptable without the si. On the one hand, one may wonder if it makes sense to study such peripheral uses of the language. On the other hand, it seems that such strengthening usage of the clitic was quite standard in early stages of Italian, while nowadays it is limited to very marked cases (see fn. 12). If that is the case, one may wonder if these diachronic differences might contribute to our understanding of the Italian clitic system from a diachronic point of view.

However, we note that qual is indeed an interrogative determiner and a proper account of qual-siasi should also take this element into consideration.

The use of the clitic mi, in this construction, has again a strengthening effect. This usage survived in current Italian only in very marked forms such as ‘Io mi pensavo che’ (I mi thought that).

http://www.ovi.cnr.it/en/, last accessed 7 May 2021.

http://www.corpusmidia.unito.it/, last accessed 7 May 2021.

http://193.205.158.203/metamotorelessico/MetamotoreLessico.html, last accessed 7 May 2021.

http://archivio.corriere.it/Archivio/interface/landing.html, last accessed 7 May 2021. The latter cannot be strictly classified as a corpus (since it is not meant to serve that purpose), but as a searchable archive of all its issues.

In particular, in o. qualsiasi occurs under the scope of a universal quantifier, strengthening its universal and generalizing meaning. We note that this construction is very marginal and usually considered odd, since qualsiasi cannot normally co-occur with a universal quantifier in the same nominal structure. The function in p. was used for idiomatic uses of the indefinite (such as the English ‘in any case’).

An example of dn found in our database is the following:

We note that this usage of qualsiasi is very marked and the indefinite alcuno, which can be normally found in negative polarity environments, sounds more natural.

This might be explained by the syntactic position of modifiers in the Italian language, which tend to prefer post-nominal positions for ind-related uses.

The availability of fc indefinites together with an indefinite article is quite typical in Romance languages and a similar construction with a numeral can already be found in Latin (e.g. unus-quivis, lit ‘one any’).

Potts (2005) uses the notion of conventional implicature to refer to the non at-issue content of a sentence. In the present paper, we will use the more neutral term ‘non at-issue content,’ highlighting the asymmetry between the two content levels.

For further diagnostics on ‘at-issue vs non at-issue content,’ see Tonhauser (2012).

It is of course difficult to prove whether this observation is due to the scarcity of the data or not. However, we observe that other unconditional uses of qual + clitic + subjunctive of to be were possible (see Sect. 2.2), but no appositional constructions of these forms were found.

It is important to underline that, from a semantic point of view, our item undergoes a type shift from an unconditional construction (where qual is a separate argument of sia together with its predicative complement) to a full determiner. We believe that multidimensional semantic approaches, which can distinguish between different content levels, might provide useful insights in this regard. In this way, the appositional stage can be seen as an intermediate context where different type shifting rules between different content levels can apply. Given the descriptive nature of this article, we leave this issue for further work.

A relevant example might be following:

As already noted, the limited number of examples makes it difficult to assess the importance of this alleged bridging stage. But the parallelism with other languages is worth noticing.

For an overview, see Dayal (2013).

It should be noted that Alternative Semantics comprises many frameworks with a variety of applications, which all originated from the original account by Hamblin (1973) (e.g. Rooth’s 1992 theory of focus interpretation, Alonso-Ovalle’s 2006 account of conditionals). In this work, with the label Alternative Semantics, we specifically refer to theories of Alternative Semantics for indefinites (e.g. Kratzer and Shimoyama 2002; Menéndez-Benito 2005; Aloni 2007; Menéndez-Benito 2010).

Note that the original account of Kratzer and Shimoyama (2002) includes also quantifiers over individual alternatives. If the alternatives introduced by an indefinite are caught by one of these quantifiers, the alternatives will not ‘grow propositional.’ This possibility is exploited by Menéndez-Benito (2005, 2010) to account for the licensing of ‘any’ in generic statements.

Technically, the framework of Alternative Semantics assumed here faces a number of well-known problems when it comes to meaning composition (see e.g. Shan 2004). Various solutions have been proposed, including the inquisitive one defended by Ciardelli et al. (2018). The analysis presented in this paper can be easily reformulated in an inquisitive semantics setting by implementing the relevant abstract operators. Given that the technicalities of meaning composition are not the main concern of this paper, we will use the Alternative Semantics formulations, which are easier to parse for a non technically-oriented reader.

See in particular the Canasta example in Menéndez-Benito (2010, 36–37).

For the role of the exhaustification operator in the treatment of fc indefinites, see in particular Menéndez-Benito (2005), who however does not assume a partition. See Aloni (2007) for another approach which leads to a partition of the logical space. Common presuppositions are existence ones, which exclude the ‘nobody’ alternative, and uniqueness ones, which exclude the ‘plural’ alternatives (e.g. \(d_{1} \, \& \, d_{2}\)).

In this sense, we can also understand why a wh-indefinite like qualsiasi naturally triggers sets of alternatives in the recursive computation of meaning.

In the formalization in (28), we modelled the sentential negative marker non with ¬, since we are dealing with a singleton set of alternatives. In general, it is of course important to examine appropriately the relationship between sentential negation and explicit negative markers in indefinites.

As noted in Sect. 2.2, si is a clitic and it is essentially semantically vacuous. Its emphatic use, however, might be due to a domain widening effect, as we speculate later when we analyze its contribution in unconditionals.

We are assuming that questions denote partitions of the logical space.

The original idea of a parallel account between unconditionals and free choice in an Alternative Semantics framework can be found in Aloni (2017).

Rawlins’ claim is quite strong: all unconditionals adjuncts are interrogative structures. This has been disputed (see e.g. AnderBois 2015). In any case, the Italian unconditional structure we are considering is formed by a transparent wh-phrase. Again the operator [Q] is needed to avoid the existential closure of the adjunct of the unconditional, as said when dealing with wh-embedded clauses above. See also Ciardelli (2016) for an inquisitive account of (un)conditionals.

In Rawlins’s theory exhaustification takes place in the question operator. The claim that exhaustification is not obligatorily triggered by wh-elements in wh-phrases, but at a different level, is not new. See e.g. Li (1995) for the role of the Mandarin particle dou in this regard.

A reviewer wonders how this analysis of unconditionals might be extended to deal with plurals (e.g. ‘whatever the gifts are, …’) and what the role of exhaustification would be in this case. We would no longer get a partition of the logical space (the singleton sets are no longer there), but only a set of mutually exclusive propositions. To still get the effect that the consequent is always true we could assume that the exclusion of the singletons is a presupposition. Alternatively, we could push the idea that the partition is still there. In particular, plurals in questions (as in ‘Which students did you meet? Only Maria.’) induce an expectation of plurality (therefore the presence of ‘only’) but a singular answer is still a possible semantic answer.

Even though Bledin (2020) argues against the idea that the main sentence is always entailed.

See in particular fn. (26).

It should be noted that our observations are mostly limited to wh-based fc indefinites, where there is a clear relationship between the bare wh-phrase and the corresponding fc indefinite. For non wh-based fc indefinites (e.g. the English any), it might be more difficult to assess the validity of our diachronic claims.

We thank an anonymous reviewer to make us aware of this line of research.

Note that assuming the configuration (a) in (34) is a common assumption in the literature on fc indefinites (e.g. Dayal 2004). Moreover, in the case of Chierchia (2013), his WSC is particularly relevant for his distinction between existential and universal free choice indefinites. In the former case, a so-called economy scale constraint blocks the structure in (a) and makes (b) the only possible option. On this, see in particular Chierchia (2013, Sect. 6.4).

For a similar modal constraint, see also Dayal (2013).

See however Chierchia and Liao (2015) for an attempt to provide a unified framework of indefinites and questions in Mandarin.

We note that our analysis applies only to the case of qualsiasi, hoping, but not claiming, that our account can be in principle generalized to other languages. It might be possible to find other items where the unconditional uses come after the fc indefinite. In this case, the universality should be accounted in a different way (see e.g. Aloni 2017 for a hypothesis about the origin of the universal meaning of the Spanish fc indefinite cualquier(a), which emerged from universally read free relatives). Similarly, it might be possible that in other cases the fc meaning is actually the result of pragmatic reasoning. This might be particular relevant for the German irgendein, as said at the end of Sect. 6.1.4.

References

Aguilar-Guevara, Ana, Maria Aloni, Angelika Port, Radek Šimık, Machteld de Vos, and Hedde Zeijlstra. 2011. Semantics and pragmatics of indefinites: Methodology for a synchronic and diachronic corpus study. In Beyond semantics: Corpus-based investigations of pragmatic and discourse phenomena, eds. Stefanie Dipper and Heike Zinsmeister, 1–16. Bochum: Bochumer Linguistische Arbeiten.

Aloni, Maria. 2007. Free choice and exhaustification: An account of subtrigging effects. In Sinn und Bedeutung 11, 16–30.

Aloni, Maria. 2017. Indefinites as fossils: The case of wh-based free choice. Paper presented at workshop Grammar of Reference and Quantification, University of Bologna.

Aloni, Maria, and Floris Roelofsen. 2014. Indefinites in comparatives. Natural Language Semantics 22(2): 145–167. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11050-013-9103-z.

Alonso-Ovalle, Luis. 2006. Disjunction in alternative semantics. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Amherst.

Alonso-Ovalle, Luis. 2009. Counterfactuals, correlatives, and disjunction. Linguistics and Philosophy 32(2): 207–244.

Alonso-Ovalle, Luis, and Paula Menéndez-Benito. 2010. Modal indefinites. Natural Language Semantics 18(1): 1–31.

AnderBois, Scott. 2015. Unconditionals in Yucatec Maya. Form and Analysis in Mayan Linguistics II (FAMLi II).

Baranzini, Laura, and Alda Mari. 2019. From epistemic modality to concessivity: Alternatives and pragmatic reasoning per absurdum. Journal of Pragmatics 142: 116–138.

Battaglia, Salvatore, and Giorgio Barberi Squarotti. 2002. Grande dizionario italiano dell’uso. Torino: UTET.

Beck, Sigrid. 2017. An alternative semantic cycle for universal quantifiers. School of Linguistics and Applied Language Studies.

Beck, Sigrid. 2020. Indeterminate pronouns in old English: A compositional semantic analysis. Journal of Comparative Germanic Linguistics 23(3): 203–269.

Becker, Misha. 1999. The some indefinites. UCLA Working Papers in Linguistics 3.

Bledin, Justin. 2020. Fatalism and the logic of unconditionals. Noûs 54(1): 126–161. https://doi.org/10.1111/nous.12257.

Bybee, Joan. 2015. Language change. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Chierchia, Gennaro. 2006. Broaden your views: Implicatures of domain widening and the “logicality” of language. Linguistic Inquiry 37(4): 535–590. https://doi.org/10.1162/ling.2006.37.4.535.

Chierchia, Gennaro. 2013. Logic in grammar: Polarity, free choice, and intervention. Oxford: Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199697977.001.0001.

Chierchia, Gennaro, and Hsiu-Chen Liao. 2015. Where do Chinese wh-items fit. In Epistemic indefinites: Exploring modality beyond the verbal domain, 31–59. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Ciardelli, Ivano. 2016. Lifting conditionals to inquisitive semantics. In Semantics and Linguistic Theory (SALT) 26, 732–752. https://doi.org/10.3765/salt.v26i0.3811.

Ciardelli, Ivano, Jeroen Groenendijk, and Floris Roelofsen. 2018. Inquisitive semantics. Oxford: Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780198814788.001.0001.

Cinque, Guglielmo. 1988. On si constructions and the theory of arb. Linguistic Inquiry 19(4): 521–581.

Company Company, Concepción. 2016. Gramaticalización y cambio sintáctico. In Enciclopedia de lingüística hispánica, ed. Javier Gutiérrez-Rexach. London: Routledge.

Company Company, Concepción, and Julia Pozas Loyo. 2006. Los indefinidos compuestos y los pronombres genérico-impersonales omne y uno. In Sintaxis histórica de la lengua española, 1073–1222. Mexico: Fondo de Cultura Económica.

Condoravdi, Cleo, and Ashwini Deo. 2014. Aspect shifts in Indo-Aryan and trajectories of semantic change. Language change at the syntax-semantics interface.

Dayal, Veneeta. 1997. Free relatives and “ever”: Identity and free choice readings. In Semantics and Linguistic Theory (SALT) 7, 99–116. https://doi.org/10.3765/salt.v7i0.2787.

Dayal, Veneeta. 1998. Any as inherently modal. Linguistics and Philosophy 21(5): 433–476. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1005494000753.

Dayal, Veneeta. 2004. The universal force of free choice. Linguistic Variation Yearbook 4(1): 5–40. https://doi.org/10.1075/livy.4.02day.

Dayal, Veneeta. 2013. A viability constraint on alternatives for free choice. In Alternatives in semantics, 88–122. Dordrecht: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137317247_4.

De Mauro, Tullio. 2000. Grande dizionario italiano dell’uso. Torino: UTET.

de Vos, Machteld. 2010. Wh dan ook: The synchronic and diachronic study of the grammaticalization of a Dutch indefinite. BA thesis, University of Amsterdam.

Deo, Ashwini. 2015a. Diachronic semantics. Annual Review of Linguistics 1(1): 179–197. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-linguist-030514-125100.

Deo, Ashwini. 2015b. The semantic and pragmatic underpinnings of grammaticalization paths: The progressive to imperfective shift. Semantics and Pragmatics 8: 14–1.

Eckardt, Regine. 2006. Meaning change in grammaticalization: An enquiry into semantic reanalysis. Oxford: Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199262601.001.0001.

Farkas, Donka F. 2002. Varieties of indefinites. In Semantics and Linguistic Theory (SALT) 12, 59–83.

Fox, Danny. 2007. Free choice and the theory of scalar implicatures. In Presupposition and implicature in compositional semantics, 71–120. Dordrecht: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230210752_4.

Gawron, Jean Mark. 2001. Universal concessive conditionals and alternative NPs in English. In Logical perspectives on language and information, eds. Cleo Condovardi and Gerard Renardel de Lavalette. Stanford: CSLI Publications. https://gawron.sdsu.edu/nuccpap.pdf.

Giannakidou, Anastasia. 2001. The meaning of free choice. Linguistics and Philosophy 24(6): 659–735. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1012758115458.

Gianollo, Chiara. 2019. Indefinites between Latin and Romance, Vol. 33. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Groenendijk, Jeroen, and Martin Stokhof. 1984. Studies on the semantics of questions and the pragmatics of answers. PhD diss., University of Amsterdam. https://hdl.handle.net/11245/1.392528.

Hamblin, Charles L. 1973. Questions in Montague English. Foundations of Language 10(1): 41–53.

Haspelmath, Martin. 1997. Indefinite pronouns. Oxford: Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780198235606.001.0001.

Haspelmath, Martin. 2003. The geometry of grammatical meaning: Semantic maps and cross-linguistic comparison. In The new psychology of language, 217–248. London: Psychology Press.

Haspelmath, Martin, and Ekkehard König. 1998. Concessive conditionals in the languages of Europe, 563–640. Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110802610.563.

Horn, Laurence R. 2005. Airport’86 revisited: Toward a unified indefinite any. The Partee Effect.

Jäger, Agnes. 2008. History of German negation. Amsterdam: Benjamins.

James, Ryan, and Andrew Weiss. 2012. An assessment of Google books’ metadata. Journal of Library Metadata 12(1): 15–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/19386389.2012.652566.

Jayez, Jacques, and Lucia M. Tovena. 2005. Free choiceness and non-individuation. Linguistics and Philosophy 28(1): 1–71.

Kadmon, Nirit, and Fred Landman. 1993. Any. Linguistics and Philosophy 16(4): 353–422. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00985272.

Kim, Min-Joo, and Stefan Kaufmann. 2007. Domain restriction in freedom of choice: A view from Korean Indet-na items. In Sinn und Bedeutung 11, 375–389.

König, Ekkehard. 1986. Conditionals, concessive conditionals and concessives: Areas of contrast, overlap and neutralization. In On conditionals, eds. Elizabeth Closs Traugott, Alice Ter Meulen, Judy Snitzer Reilly, and Charles A. Ferguson, 229–246. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Kratzer, Angelika. 1986. Conditionals. Chicago Linguistics Society 22(2): 1–15.

Kratzer, Angelika. 2005. Indefinites and the operators they depend on: From Japanese to Salish. In Reference and quantification: The Partee effect 173, 113–142. http://press.uchicago.edu/ucp/books/book/distributed/R/bo3685994.html.

Kratzer, Angelika, and Junko Shimoyama. 2002. Indeterminate pronouns: The view from Japanese. In Paper presented at the 3rd Tokyo conference on psycholinguistics. https://people.umass.edu/partee/RGGU_2004/Indeterminate%20Pronouns.pdf.

Lewis, David. 1975. Adverbs of quantification. In Formal semantics of natural language, ed. Edward L. Keenan, 178–188. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.