Abstract

Aims

The aim was to quantify the nitrogen (N) transferred via the extra-radical mycelium of the arbuscular mycorrhizal fungus Glomus intraradices from both a dead host and a dead non-host donor root to a receiver tomato plant. The effect of a physical disruption of the soil containing donor plant roots and fungal mycelium on the effectiveness of N transfer was also examined.

Methods

The root systems of the donor (wild type tomato plants or the mycorrhiza-defective rmc mutant tomato) and the receiver plants were separated by a 30 μm mesh, penetrable by hyphae but not by the roots. Both donor genotypes produced a similar quantity of biomass and had a similar nutrient status. Two weeks after the supply of 15 N to a split-root part of donor plants, the shoots were removed to kill the plants. The quantity of N transferred from the dead roots into the receiver plants was measured after a further 2 weeks.

Results

Up to 10.6 % of donor-root 15N was recovered in the receiver plants when inoculated with the arbuscular mycorrhizal fungus (AMF). The quantity of 15N derived from the mycorrhizal wild type roots clearly exceeded that from the only weakly surface-colonised rmc roots. Hyphal length in the donor rmc root compartments was only about half that in the wild type compartments. The disruption of the soil led to a significantly increased AMF-mediated transfer of N to the receiver plants.

Conclusions

The transfer of N from dead roots can be enhanced by AMF, especially when the donor roots have been formerly colonised by AMF. The transfer can be further increased with higher hyphae length densities, and the present data also suggest that a direct link between receiver mycelium and internal fungal structures in dead roots may in addition facilitate N transfer. The mechanical disruption of soil containing dead roots may increase the subsequent availability of nutrients, thus promoting mycorrhizal N uptake. When associated with a living plant, the external mycelium of G. intraradices is readily able to re-establish itself in the soil following disruption and functions as a transfer vessel.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In terrestrial ecosystems, root turnover is a key component of belowground nutrient cycling, and so provides an important source of nutrients for plant growth. The quantity of nutrient released from dead roots can be substantial, although it differs from plant species to plant species. Aerts et al. (1992) estimated the volume of organic nitrogen (N) turnover in soil associated with root decay to be 1.7 g N m−² yr−1 in Deschampsia and 19.7 g N m −2 yr −1 in Molinia grasslands. Detached Holcus grass roots lose up to 87 % of their initial N within 42 days and approximately 40 % of it is taken up by other plants (Van der Krift et al. (2001). The activity of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF) may enhance the ability of plants to recycle nutrients from dead roots (Grime et al. 1987). Moreover, AMF networks may link different mycorrhizal plant species and so provide access to N derived from the roots of distant plants. Interconnected mycorrhizal plants may be more competitive than non-mycorrhizal species or those which are less responsive to mycorrhiza (Hartnett et al. 1993). The use of isotope-labelled phosphorus has shown that AMF mycelia can transfer nutrients over a distance of as much as 50 cm (Walter et al. 1996). The application of 15N-enrichment technology in the substrates of AMF compartments (accessible to AMF but not to roots) has enabled the quantification of soil-to-plant N transfer via the AMF extra-radical mycelium (ERM) from inorganic as well as organic N sources (Ames et al. 1983; Frey and Schüepp 1993; Johansen et al. 1992; Johansen et al. 1994; Hawkins et al. 2000; Hawkins and George 2001; Mäder et al. 2000; Hodge et al. 2001; Cheng et al. 2008). For example, about 30 % of receiver plant N content derived from AMF N transfer (Ames et al. 1983; Frey and Schüepp 1993; Mäder et al. 2000) suggesting that AMF may have a large potential to improve N nutrition of host plants.

Only a few studies have investigated N transfer between live mycorrhizal plants where roots have been separated by an AMF accessible barrier (Haystead et al. 1988; Bethlenfalvay et al. 1991; Hamel et al. 1991; Ikram et al. 1994; Johansen and Jensen 1996; Jalonen et al. 2009; Li et al. 2009). A possible undesirable side-effect of such an experimental set-up is the development of a larger root system in AMF colonised donor plants, due to the presence of the symbiont. This may produce a larger nutrient pool, especially in legume species (Haystead et al. 1988; Li et al. 2009), and make the level of N transfer difficult to interpret. The extent of AMF mediated N transfer is only minor from the live root, while killing the root by removal of the shoot can enhance the quantity of N transfer (Johansen and Jensen 1996). The implication is that dead roots are a much more effective source of transferrable N than are root exudates from living plants. However, the relative contributions of live roots, dead roots and rhizodeposition products to fungal N transfer remain to be clarified. The direct uptake of N from the inner cortex of live roots by hyphae is unlikely, as it would contradict the accepted idea about a two-sided mycelium functioning, i.e. the site of N uptake and anabolic assimilation into the fungal tissue is thought to be the ERM, while N is catabolised within the intra-radical mycelium (IRM) and then released to the host plant via the arbuscules (Govindarajulu et al. 2005; Tian et al. 2010). What occurs subsequent to the dieback of colonised donor plant roots is unclear. It appears possible, however, that the AM symbiosis can facilitate the efficient (re-) absorption of root N, so that this root N is transferred directly to the receiver host plant, rather than to the rhizosphere soil, soil-borne microorganisms or non-host plants.

The initial objective of the present study was to quantify the extent of mycorrhizal N transfer from the dead roots of a donor plant to a receiver plant. The working hypothesis was that a greater quantity of N is transferred from dead mycorrhizal roots than from dead non-mycorrhizal ones. To test this, a comparison was made between a wild type [WT] tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L. cv. RioGrande 76R) and a mycorrhiza-defective [rmc] mutant tomato. The latter cannot support intra-radical colonisation by Glomus intraradices (Barker et al. 1998) but its above and below ground biomass production is similar to that of the WT (Cavagnaro et al. 2006; Bago et al. 2006). The second aim was to asses the ability of the ERM to absorb and subsequently transfer N following physical damage to the AMF network caused by tillage, which has been repeatedly shown to reduce the infectivity of a mycelium (McGonigle et al. 1990; Jasper et al. 1991). Furthermore, the re-establishment of the network and fungal mediated N transport can be clearly reduced following the severe disruption of the ERM (Frey and Schüepp 1993). Nevertheless, various AMF isolates can differ considerably from one another in terms of their sensitivity to mechanical disruption (Duan et al. 2011).

Materials and methods

Pre-cultivation of plant material

Seeds of the mycorrhiza-defective [rmc] mutant (Barker et al. 1998) and the wild type [WT] progenitor Solanum lycopersicum (L.) cv. RioGrande 76R were germinated in the dark between two layers of paper soaked with saturated CaSO4 solution. To obtain seedlings with a root system suitable to be split between two pots, plants were pre-cultivated in nutrient solution. Therefore, at a height of 5–6 cm germinated seedlings were transferred to an aerated nutrient solution (pH 6.8) composed of the following: 5 mM N (half Ca(NO3)2, half NH4NO3); 0.7 mM P (KH2PO4); 4 mM K (KH2PO4 and K2SO4); 2.5 mM Ca (Ca(NO3)2 and CaSO4); 1 mM Mg (MgCl2); 4 mM S (CaSO4 and K2SO4); 10 μM Fe (Fe-EDTA); 10 μM B (H3BO4), 5 μM Mn (MnSO4); 1 μM Zn (ZnSO4); 0.7 μM Cu (CuSO4); 0.5 μM Mo ((NH4)6Mo7O24). Fourteen days after transfer to nutrient solution, the main root of each tomato plant was cut off 1 cm above the tip to break apical dominance. The plants were grown another 2 weeks before transplantation to the experimental planting units.

Preparation of growth substrate and planting units

Tripartite planting units were constructed consisting of three square plastic pots (Teku-Tainer, Pöppelmann, Germany), placed in a row and fastened together with adhesive tape. One of the outer pots (compartments), with a volume of 0.5 L, served as the 15N labelling compartment (LC). The other two compartments, with a volume of 1.2 L, served as ‘donor’ (DC) and ‘receiver’ (RC) root compartments, respectively (see Fig. 1a). To allow for the growth of AMF mycelia but not of roots between the two larger compartments, a fungal window (height = 7 cm; width = 6 cm) comprising of a 30 μm mesh membrane (Sefar Nitex; Sefar AG, Switzerland) was cut into the two adjoining walls. Each 1.2 L and 0.5 L compartment was filled with 1.4 kg and 0.6 kg dry substrate, respectively. Material from the C-horizon of a Luvisol from Weihenstephan, southern Germany (48°25′N, 11°50′E) was used for the growth substrate. The substrate was classified as loamy sand (45.2 % sand, 42.0 % silt, 12.8 % clay). To eliminate AMF propagules it was dry heated twice for 24 h at 85 °C, each time followed by a storage period of 24 h at room temperature (modified after Smit et al. 2000). Before heating, the substrate contained (mg kg−1) 5.2 and 3.4 CaCl2 (0.0125 M)-extractable NH +4 and NO -3 , respectively. After heating, the organic matter content was 0.3 % (w/w), and the substrate had a pH (CaCl2) of 7.7. After heating the material contained (mg kg−1) 6.5 acetate lactate-extractable (CAL, Schüller 1969) P; 65.7 CAL-extractable K; and 15.0 (Mn), 0.3 (Zn) and 0.9 (Cu) CAT-extractable (Alt and Peters 1993) micronutrients. The substrate was fertilised with 200 mg K (K2SO4), 100 mg N (NH4NO3), 100 mg Mg (MgSO4), 50 mg P (KH2PO4), 10 mg Fe (Fe-EDTA), 10 mg Cu (CuSO4), 10 mg Zn (ZnSO4) per kg dry substrate.

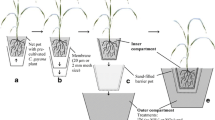

Longitudinal section illustrating the tripartite planting unit. a The roots of a donor plant (either wild type WT or a mycorrhiza-defective rmc mutant) were split between the donor root compartment (DC) and the 15N-labelling compartment (LC). The receiver root compartment (RC) contained a WT tomato plant in each case. The RC and DC root compartments were separated from another by a 30 μm mesh membrane penetrable by AMF hyphae but not by roots. Both root compartments contained one fungal compartment (FC) each. Subsequent to a 2-week labelling period, the LC and the donor shoots were removed and the substrate in the DC was either (b) left undisturbed (substrate treatment [U]) or (c) was mechanically disrupted (substrate treatment [X])

Arbuscular mycorrhizal inoculation and installation of fungal compartments

Inoculum of the AM fungus Glomus intraradices was used (Glintra IFP S/08; provided by INOQ GmbH; Schnega; Germany). It consisted of a mixture of AMF colonised roots with adhering growth substrate (quartz sand) and extra-radical mycelium with spores. To prepare mycorrhizal treatments, living inoculum was mixed with the experimental growth substrate at a rate of 7 % (w/w). The substrate in all three compartments of each planting pot was either prepared as AM inoculated [+AM], or as non-inoculated [-AM] substrate. The inoculum for [-AM] treatments was filtered with deionised water (100 ml per 50 g dry inoculum through Blue Ribbon filter paper, Schleicher and Schüll, Germany) before it was dry heated for 48 h at 85 °C to eliminate AMF propagules. The filtrate was added to [-AM] substrate to encourage a similar microflora as in [+AM] treatments.

Fungal compartments for vertical insertion into the growth substrate were constructed from 70 ml grid tubes with a latticed wall (Teku G5R, Pöppelmann, Germany), surrounded by a 30 μm mesh membrane (Sefar Nitex; Sefar AG, Switzerland). Each fungal compartment was filled with 55 ml of a 1:1 (weight) mixture of 40 μm wet sieved substrate (the same as used for pot filling) and glass beads (diameter 1–2 mm). This mixture has chemical conditions similar to the experimental substrate but allows for the efficient extraction of AM extra-radical mycelium from the fungal compartments (Neumann and George 2005). The sieved material was dry heated and fertilised in the same way as the substrate used for the planting pots. One fungal compartment each was installed into the DC and the RC, respectively, near the fungal window (see Fig. 1a).

Plant cultivation, 15N application and set-up of the donor plant treatments

At the age of 28 days, one wild type tomato [WT] ‘receiver’ plant was transferred from the nutrient solution into the centre of the receiver compartment, RC. At that time also one ‘donor’ plant, either [WT] or [rmc], was transferred into the labelling compartment (LC) and donor compartment (DC) with its root system split (see Fig. 1a). In total, 32 planting units were established.

Thirty days after planting, the substrate in the LC was supplied once with additional 240 mg N kg−1 dry substrate as Ca(NO3)2 that contained 10 atom% 15N isotope (Chemotrade GmbH, Leipzig, Germany). Fourteen days after 15 N application, all LCs together with the split-root parts contained therein, were completely removed from the donor plants and the planting units. At that time all donor plant shoots were harvested one cm above the soil surface (Fig. 1b and c). The growth substrate in the DC of harvested plants was either left undisturbed ([U]; Fig. 1b) or was disrupted ([X]; Fig. 1c, Table 1). To create disruption, the substrate inside the DC was cut vertically into columns of approximately 1 cm size and vertically mixed by hand using a spatula. Fungal compartments were removed from the DC during this process and were re-installed afterwards. The experimental plants were grown for 72 days in a glasshouse between September and November, the average day and night temperature was 22 °C and 17 °C, respectively, and the relative air humidity averaged 71 %. For the last 42 days the plants received additional light for 8 h during the day at a rate of 380 μmol m−2 s−1 delivered at plant height by 400 W lamps (SON-T Agro; Philips, Germany). Daily water loss from the planting units was estimated gravimetrically and replaced with deionised water. The irrigation water was distributed among the three compartments of each planting unit, in order to maintain average soil water content in each compartment at approximately 18 % (w/w).

Harvest and analysis of plant and AMF material

Receiver plants and the roots from donor compartments (DC) were harvested another 14 days after termination of the 15N labelling period and donor shoot removal. All roots were washed free from the substrate, and a representative sample of the fresh roots (approximately 1 g) was taken from each root compartment and stained with trypan blue in lactic acid according to Koske and Gemma (1989). The extent of AMF root colonisation was then estimated by a modified grid line intersection method (Tennant 1975). As intra-radical AMF structures were absent from rmc roots, values for these plants represent root surface colonisation by appressoria and attached hyphae only. The harvested plant material (shoot or root) was dried for 48 h at 65 °C before the dry weight (DW) was estimated. Biomass analyses for the different donor root fractions, split between the LC and the DC, were conducted separately.

The content of the fungal compartments was washed through a 40 μm sieve, and the extra-radical mycelium was extracted and freeze-dried according to Neumann and George (2005). After the DW of the ERM had been determined, subsamples of approximately 0.5 mg were transferred to 2.5 ml Eppendorf tubes and stained overnight at room temperature with a few drops of 0.05 % trypan blue in lactic acid. Stained samples were transferred to a laboratory blender (Waring Blender 7009G, Waring, USA) with 200 ml tap water, and blended at low speed for 40 s. Aliquots of 90 ml of the suspension were used to assess the length of hyphae and the number of AM spores by the membrane filter method (Hanssen et al. 1974).

Subsamples of 200 mg of ground plant material were dry ashed at 550 °C, oxidized with 5 ml 21 % HNO3, and taken up into 25 ml of 1.2 % HCl. The P concentration in the samples was then estimated colorimetrically with a spectrophotometer (EPOS analyzer, Eppendorf, Germany) at 436 nm wavelength, after staining with ammonium-molybdate-vanadate solution (Gericke and Kurmies 1952). To analyse the ground plant material for N, subsamples of 10 mg were submitted to an autoanalyser (Elementar Vario EL, Elementar, Germany). A proportion of the sample combustion gas was introduced into a coupled isotopic ratio mass spectrometer (TruSpec, LECO Corporation, USA), and 15N in atom% of the total N exceeding natural abundance was determined.

P and N analyses for the donor roots grown in the LC and the DC were conducted separately.

Calculations and statistics

Assuming that 14N and 15N are both taken up and transferred in equal quantities, the relative amount of N transferred from the donor to receiver plant (%Ntransfer) was estimated from the ratio between 15N content in the receiver plant and the sum of 15N contents in both the receiver and donor plant. The %Ntransfer was calculated using the donor plant total 15N content comprising the labelled N contents in shoot and both split-root parts from the labelling compartments (LC) and donor root compartments (DC). This was calculated as follows:

where

Since donor shoots and the LC were removed 14 days after labelling and 14 days before the harvest of the receiver plants, it may also be meaningful to estimate the N transfer percentage by taking into account only the N content in donor roots from the DC. Accordingly, the percentage N transferred to receiver plants from donor roots (%Root Ntransfer) was calculated as (according to Johansen and Jensen 1996):

The amount of N (mg plant−1) transferred from the donor root (Root Ntransfer) was estimated with the following equation:

The % of total N recovered in the receiver, derived from transfer (%NdfT), was calculated as:

Four replicates per treatment were used. Provided that results passed the test for normal distribution (Kolmogorov-Smirnov test; p > 0.05) and homogeneity of variance (Levène test; p > 0.05), data were subjected to three-way ANOVA. Data for 15N contents in receiver plant tissue were normalised by square root transformation prior to statistical analysis. In cases where the ANOVA indicated a significant effect of any factor, the multiple comparison Tukey-test was used to estimate differences between means of all treatments. P values below 0.05 obtained in both tests were interpreted as indicating significant effects. Statistic calculations were conducted using SPSS software, version 15.0 (SPSS Inc., USA). Results in tables and figures are presented as treatment means ± standard deviation.

Results

Dry weight and nutrient status of the donor plants

Donor plant dry weight and shoot phosphorus (P) concentration were not affected by genotype or AMF inoculation (data not shown). Root dry weight was also similar between undisturbed and disrupted soil treatments (Tables 2 and 3). The labelling compartment (LC) was removed from the growth unit after the labelling period, and the values measured for the nutritional status of roots from the LC in all cases reflected the results shown for the split-root part from the DC. Therefore no further results for root parts from the LC are shown. AMF inoculation lead to significantly higher root P concentrations in WT donor roots compared to non-inoculated controls. In contrast, rmc mutant plants showed no significant response to the presence of mycorrhiza (Tables 2 and 3). However, total P content in the plants was not affected by AMF inoculation or genotype (Tables S1 and S2). As a result of disruption of roots and mycelium in [X] treatments, P concentration (Tables 2 and 3) and P content (Tables S1 and S2) in donor roots were reduced by about one third compared to the undisturbed [U] treatment.

Across all treatments the average shoot nitrogen (N) concentration of donor plants averaged 18.2 ± 1.8 mg g-1 DW and was not affected by the genotype or AMF inoculation treatments. Total plant N content (data not shown) and total N content in roots were similar between the two genotypes (WT and rmc), irrespective of the AMF inoculation (Tables S1 and S2). Across all treatments the average 15N content in shoots at harvest was 10.8 ± 0.5 mg per plant, and together with the total 15N content in donor roots (Tables S1 and S2) was not affected by the genotype or disturbance treatment. Independent of the treatments the average quantity of 15N recovered in the whole donor plant was 65 ± 11 % of the amount applied to the labelling compartments of donor plants (about 16 mg 15N was applied per plant; data not shown).

All the information above allows us to show that the experimental plants of both genotypes had a similar biomass and nutrient status, which was critical for the WT and non-mycorrhizal rmc donor plant treatment. Consequently, AMF mediated N transfer could be quantified from donor plants of similar characteristics, being either colonised by AMF or not.

Intra- and extra-radical AMF development

The AMF colonised root length of all AMF-inoculated WT donor roots was 50–70 % (Table 4), including appressoria on the root surface with attached extra-radical hyphae, spores, and intra-radical fungal structures. Donor roots of rmc mutant plants showed a colonisation rate between 12 % and 16 % (Table 4). These plants had a surface colonisation, consisting of appressoria, attached extra-radical hyphae and spores. No intra-radical fungal structures were found inside of decomposing rmc mutant roots, with the exception of a few instances where intra-radical AMF spores were present. These spore clusters colonised a root length of not more than 1.2 ± 0.9 %. Receiver root colonisation rates (WT only) ranged between 60 % and 70 % and were unaffected by the soil treatments in the DC (Tables 4 and 5). No AMF colonisation was observed in non-inoculated treatments.

At the end of the experiment, in all AMF-inoculated treatments the average dry weight of the ERM from the donor fungal compartments was 0.3 ± 0.1 mg cm−3 across all treatments (data not shown). No fungal material was observed in non-inoculated compartments. When the donor root was left untreated [U], the external mycelium in WT donor fungal compartments developed approximately four times higher hyphae lengths and spore amounts per volume substrate compared to the ERM of the rmc donor fungal compartments (Fig. 2). The disruption treatment [X] did not significantly affect the hyphae length or spore number compared with the undisrupted situation (Table 5). In contrast, hyphae length and spore density of the ERM obtained from fungal compartments of the receiver root compartments were not significantly affected by genotype or disruption of the neighbouring donor plant root (Fig. 2; Table 5).

Development of the extra-radical mycelium obtained from fungal compartments located in root compartments of either donor (DC; a, b) or receiver (RC; c, d) plants. Hyphae length density and spore density in the substrate are shown. Means followed by a different letter differ significantly from another according to a multiple comparison Tukey-test (p < 0.05), as induced by the factors donor genotype [WT vs rmc] or substrate treatment in donor compartments [U vs X]

Dry weight and nutrient status of the receiver plants

Receiver plant dry weight and P status

Shoot or root biomass (Tables 6 and 7) and ratio of shoot-to-root DW (data not shown) were not affected by the donor plant genotype, donor substrate treatment or AMF inoculation. The total P content of receiver plant tissue did not differ due to the neighbour plant’s genotype or substrate treatment (Tables S3 and S4). When inoculated with AMF the shoot and root P concentration (Tables 6 and 7) as well as the total P content (Tables S3 and S4) in receiver plants were significantly increased compared to non-inoculated plants.

Receiver plant status of total nitrogen and 15N

Receiver shoot N concentration and also total shoot N content (data not shown) were not significantly affected by any of the experimental treatments. When the donor plant was an undisturbed rmc plant, a significantly higher N concentration and content (data not shown) were recorded in AMF-inoculated receiver roots compared to non-inoculated treatments. However, total N content in the receiver plant tissue was similar among all the treatments (data not shown).

15N transfer from the donor to the receiver plant was clearly affected by the treatments: Significantly higher contents of 15N were found in AMF-inoculated than in non-inoculated receiver plants (Tables S3 and S4). Only when AMF-inoculated, the quantity of 15N derived from WT plants clearly exceeded that from rmc donor plants. In undisturbed and AMF-inoculated treatments the quantity of 15N in receiver plants originating from rmc mutant roots of plants was low and in a similar range to than that of non-inoculated receiver plants. After the disruption of the donor plant substrate, AMF inoculated receiver plants obtained at least twice the amount of labelled N compared to the undisturbed treatment, irrespective of the donor plant genotype (Table S3).

The amount of total N transferred during the experiment (%Ntransfer; Eqs. 1 and 2) was up to 1.5 ± 0.5 % in WT plants and up to 0.5 ± 0.2 % in rmc plants. The highest percentage of receiver total N content that derived from fungal transfer (%NdfT; Eqs. 4 and 5) was found in WT treatments and amounted up to 0.4 ± 0.1 % in the undisturbed and 1.1 ± 0.5 % in the disturbed treatment.

The %Root Ntransfer to receiver plants (calculated with Eq. 3) was significantly higher when donor roots were AMF inoculated compared to the very low levels of non-inoculated plants (Fig. 3; Table 7). In presence of the AM fungus, average %Root Ntransfer from WT donor roots (3.4 ± 1.6 %) clearly exceeded that from rmc roots (0.3 ± 0.4 %). This effect was further enhanced by the disruption of donor roots: soil disruption increased the amount of N transfer from AMF-inoculated roots of WT to 10.6 ± 4.8 % and that of rmc roots to 3.8 ± 1.5 % (Fig. 3). The interaction between donor genotype and AMF inoculation was statistically significant (Table 7).

%Root Ntransfer to receiver plants. Different letters indicate significantly different mean values (multiple comparison Tukey-test; p < 0.05), as induced by the factors donor [WT vs rmc], presence of AMF inoculation [+AM vs −AM] and donor substrate treatment [U vs X]. Prior to statistical analysis, the data were normalised by square root transformation

Discussion

Symbiotic N transfer from mycorrhizal and non-mycorrhizal dead roots

Many tomato cultivars are unresponsive to AMF in terms of growth (Bryla and Koide 1990), including ‘RioGrande 76R’ used in the present experiment (Neumann and George 2005). Furthermore, the use of the tomato rmc mutant allows quantifying the capacity of AMF mycelium to transfer N between roots which differed with respect to their ability to support mycorrhizal colonisation but without confounding effects of differences in plant biomass. In fact, neither the dry matter production nor the total N and P content of donor and receiver plants was significantly affected by the genotype of the donor. Therewith, all receiver plants had a similar nutrient demand when grown either adjacent to a wild type or to an rmc mutant plant and on the other hand the donor plants all represented an N source of equivalent magnitude.

As also revealed by Johansen and Jensen (1996), the volume of N transferred to a receiver plant from dead roots of a donor was significantly increased when the roots were mycorrhizal. The two root systems were physically isolated from one another by a nylon mesh which, nevertheless, allowed a limited extent of direct transfer between adjacent non-inoculated roots. For example, in undisrupted treatments direct transfer in the non-inoculated WT treatment was approximately 7 % of that measured in the inoculated WT treatment. This form of direct N transfer is most likely to reflect the re-absorption of donor root N-losses by the receiver root, as also demonstrated by Li et al. (2009).

After a 2 week-period after shoot removal from donor plants, the amount of 15N present in each receiver plants increased from 2 to 8 μg (not inoculated) to 30–90 μg per plant (inoculated with AMF). The proportion of the donor root N transferred (%RootNtransfer) reached 13 %. That was about one sixth of the donor root N content still available at the end of the experiment had been recovered by the receiver plants. Related to the total N content of receiver plants the proportion of N derived from fungal transfer (%NdfT) was <1 %, irrespective of soil disturbance. Similar levels of N transfer between root systems connected by AMF mycelia have been reported by Johansen and Jensen (1996). This indicates that under the present experimental conditions the quantity of AM fungal N transfer from plant residues cannot be sufficient to have a positive impact on plant N nutrition compared to total plant N uptake, presumably mostly by roots. Fresh plant residues in soil in many circumstances are rapidly mineralised (Nett et al. 2010), and hence are a direct source for N for subsequent and neighbouring plants. Also under the present experimental conditions N losses from donor roots would have increased with a longer time of 15N exposure, as also shown by Ames et al. (1983) and Jalonen et al. (2009).

The contribution of AMF to plant N nutrition may be more important in a field situation, where mycorrhizal plants grow rather slowly and/or plant N demand exceeds its availability. This situation arises when, for example, N sources are present in an immobile form, or when drought stress limits the ability of roots to absorb nutrients from soil (Tobar et al. 1994; Subramanian and Charest 1999).

AMF-mediated N transfer as affected by the presence of mycelium within the donor root

Possible sources of AMF-mediated 15N uptake and transfer included (1) N in the substrate around donor roots, derived from rhizodeposition by live donor roots during the labelling period and from losses by root decay after shoot removal, and (2) N from inside the colonised donor root. The latter was accessible to AM mycelium connected to the receiver plant either directly from the cortex via the former intra-radical mycelium (IRM), or mobilised from fungal storage structures inside the root (vesicles). The use of the rmc mutant (lacking intra-radical colonisation) in the present experiment allowed for the separate quantification of N transfer based on the uptake via the pathway (1) (WT and rmc plants) and pathway (2) (WT plants only). Here it was shown that the extent of symbiotic N recapture was clearly determined by the donor plant’s genotype—i.e., mycorrhizal (WT) as opposed to non-mycorrhizal (rmc mutant). Nearly three times more N was transferred from inoculated WT than from the corresponding rmc mutant donor root (Table 6). Since the major source of transferred N was in the substrate released by dead donor roots, hyphal length close to the donor root may be a relevant factor. Note that the external mycelium in the rmc donor compartments was allowed to enter by means of the fungal window inserted between both neighbouring plants and therefore the fungus was likely in symbiosis with the receiver root. We observed that the fungal biomass and hyphae length in the WT compartments doubled that found in the rmc compartments.

Based on isotope-labelled fertilisation of fungal compartments, it has been shown that hyphal length density in the soil is positively correlated with the capacity of the AMF to absorb and transfer both N (Ames et al. 1983) and P (Smith et al. 2004; Jansa et al. 2005). Therefore, the observed difference in N transfer between the WT and rmc roots may at least partly be attributable to differences in hyphal density in donor root compartments, as parts of these hyphae were associated with receiver plants.

The pattern of root colonisation is important in the context of an N source derived from the internal structure of the root. The proportion of the WT root length colonised by AMF following inoculation was 50–70 %, while in the rmc root, AMF were restricted to the root surface (12–16 %) and formed only appressoria, i.e., hyphal swellings on the root epidermis. The extent of the rmc tomato mutant root surface colonised by a mixture of Glomus mosseae and Glomus intraradices was of the same order as shown by Neumann and George (2005). Even after the demise of the rmc donor roots, in the present study the only intra-radical colonisation was a small number of intra-radical spores occupying not more than 2 % of the root length. Root internal vesicles have a relevant potential to establish new root infection (Biermann and Lindermann 1983), and represent a significant location for the storage of nutrient reserves (van Aarle and Olsson 2003), to be exported to the ERM as the fungus grows (Bago et al. 2002). In view of the differences in ERM density between the WT and the rmc donor root compartments, it remains unclear to what extent intra-radical fungal structures in colonised WT donor roots contributed to the quantity of N transferred. However, following the demise of the root, the former IRM may have been able to grow and later fuse with the symbiotic ERM originating from the receiver root compartment, facilitating transfer of N also from root-internal fungal structures to the receiver.

Effect of soil disruption on N transfer to receiver plants

The effects of soil disturbance observed in the field and in pot experiments have been inconsistent, for example, host plant colonisation by AMF was decreased (Evans and Miller 1988; Jasper et al. 1989; Jasper et al. 1991), and as a consequence also a the AM fungal contribution to plant growth has been reduced (McGonigle et al. 1990), in other cases disruption had no consequences (McGonigle and Miller 2000). The effect of disruption of the hyphae during the plant growth period and the resulting consequences for AMF nutrient transfer is less well explored. Periodic mechanical disruption of the ERM located in root-free and isotope-labelled fungal compartments has been shown to reduce the soil-to-plant transfer of both N (Frey and Schüepp 1993) and P (Tuffen et al. 2002; Duan et al. 2011). Such a repeated and severe disruption of the AMF network must reduce the capacity of the AMF to absorb nutrients, as also suggested earlier (Evans and Miller 1990). Here, uniquely, mycelium was disrupted only once (as in a single tillage procedure) and root residues were used as N source (as they are usually present in vegetated soils). Under these conditions, the disruption in donor root compartments lead to higher 15N content in the receiver plants compared with undisrupted treatments. This effect was unexpected in light of earlier studies where disruption had decreased fungal nutrient transfer.

Two reasons may be responsible for the higher N transfer by hyphae after soil disruption in the present experiment. Firstly, root death can be followed by a substantial loss of nutrients from the root tissue due to autolysis (Wichern et al. 2007). For example, excised roots of rye grass incubated in soil for 3 weeks lose up to, respectively, 60 % and 70 % of their initial N and P (Eason and Newman 1990), and these nutrients rapidly become available to plant roots (Ritz and Newman 1985; Eissenstat 1990). Within a few days after mechanical disturbance, soil samples taken from a tilled field site showed a higher level of net N mineralisation accompanied by the continuous accumulation of nitrate susceptible to leaching than did soil sampled from an undisturbed site (Jackson et al. 2003). A similar contrast has been shown to apply in the comparison between sieved and non-sieved field soil samples (Calderon et al. 2000). The major effect of soil disruption in the present study included the fragmentation of the 15N-labelled donor roots, which very likely resulted in an increased root surface area exposed to microbial degradation thereby increasing N ad P losses from roots. Indeed, when the soil was disrupted P concentrations were reduced compared to undisturbed donor roots (Table 2), suggesting that more nutrients were available to hyphae in disrupted soil perhaps because of leaching from damaged tissue.

Secondly, a one-time disturbance may be quickly overcome by hyphae of some AM fungi. Representatives of the Glomus family typically develop rapidly in the soil, and the hyphal network of Glomus intraradices appears to be quite insensitive to soil disruption with respect to following root colonisation (Duan et al. 2011). Mikkelsen et al. (2008) recorded a rate of advance of the hyphal front in soil of up to 3.8 mm per day, and Giovannetti et al. (1993) measured the elongation of germinated hyphae of up to approximately 5 mm per day. Injured hyphae of Glomus isolates are able to anastomose within minutes (de la Providencia et al. 2005), reflecting the species well-developed capacity to repair its ERM network following disturbance. Here, provided that the fungal mycelium was in continuous symbiotic association with the (undisturbed) receiver plant, the 2-week interval between soil disruption and harvest was apparently sufficient for the fungus to enter the donor root compartment. Spreading from the receiver compartment, the mycelium may have entered the donor root compartment, building linkages across the fragmented mycelium. This process would have enabled the ERM network to function once more with respect to N uptake and transfer, whether the donor was a mycorrhizal or a non-mycorrhizal plant. Thus, together the new establishment by the fungus in the donor compartment and an increased availability of N from roots fragmented by soil disturbance could explain the higher fungal N transfer from both the inoculated WT and the rmc mutant donor roots compared with the non-inoculated treatments.

In conclusion, it has been possible to confirm that the quantity of N transferred between two root systems can be enhanced by the presence of AMF extra-radical mycelia. The quantity of N transferred during the short experimental duration was substantial compared to the total amount of N in the dead roots, but relatively small compared to the total N demand of a fast growing plant. Mycorrhizal N transfer from dying roots was further increased when these roots were AMF colonised before death. This difference can be reasoned by higher mycelium densities in the soil around the roots or by export of N reserves from root internal fungal structures through linkages to the receiver mycelium. Mechanical disruption to a soil containing dead roots can increase the availability of nutrients and therefore assist the process of mycorrhizal nutrient uptake and transfer. When associated with a living plant, G. intraradices appears to have a high potential to re-establish its network in the soil after disruption, and to function as a vehicle of N transfer. Agricultural practices, including reduced tillage may increase nutrient availability from plant residues and rather have a positive effect on AM symbiosis when involving fungi unsusceptible to a single mechanical disruption.

References

Aerts R, Bakker C, Decaluwe H (1992) Root turnover as determinant of the cycling of C, N, and P in a dry heathland ecosystem. Biogeochemistry 15:175–190

Alt D, Peters I (1993) Analysis of macro- and trace elements in horticultural substrates by means of the CaCl2/DTPA method. Acta Hort 342:287–292

Ames RN, Reid CPP, Porter LK, Cambardella C (1983) Hyphal uptake and transport of nitrogen from two N-15-labeled sources by Glomus mosseae, a vesicular arbuscular mycorrhizal fungus. New Phytol 95:381–396

Bago B, Zipfel W, Williams RM, Jun J, Arreola R, Lammers PJ, Pfeffer PE, Shachar-Hill Y (2002) Translocation and utilization of fungal storage lipid in the arbuscular mycorrhizal symbiosis. Plant Physiol 128:108–124

Bago A, Cano C, Toussaint JP, Smith S, Dickson S (2006) Interactions between the arbuscular mycorrhizal (AM) fungus Glomus intraradices and nontransformed tomato roots of either wild-type or AM-defective phenotypes in monoxenic cultures. Mycorrhiza 16:429–436

Barker SJ, Stummer B, Gao L, Dispain I, O’Connor PJ, Smith SE (1998) A mutant in Lycopersicon esculentum Mill. with highly reduced VA mycorrhizal colonization: isolation and preliminary characterisation. Plant J 15:791–797

Bethlenfalvay GJ, Reyessolis MG, Camel SB, Ferreracerrato R (1991) Nutrient transfer between the root zones of soybean and maize plants connected by a common mycorrhizal mycelium. Physiol Plantarum 82:423–432

Biermann B, Lindermann RG (1983) Use of vesicular-arbuscular mycorrhizal roots, intra-radical vesicles and extra-radical vesicles as inoculum. New Phytol 95:97–105

Bryla DR, Koide RT (1990) Role of mycorrhizal infection in the growth and reproduction of wild vs. cultivated plants. II. Eight wild accessions and two cultivars of Lycopersicon esculentum Mill. Oecologia 84:82–92

Calderon FJ, Jackson LE, Scow KM, Rolston DE (2000) Microbial responses to simulated tillage in cultivated and uncultivated soils. Soil Biol Biochem 32:1547–1559

Cavagnaro TR, Jackson LE, Six J, Ferris H, Goyal S, Asami D, Scow KM (2006) Arbuscular mycorrhizas, microbial communities, nutrient availability and soil aggregates in organic tomato production. Plant Soil 282:209–225

Cheng XM, Euliss A, Baumgartner K (2008) Nitrogen capture by grapevine roots and arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi from legume cover-crop residues under low rates of mineral fertilization. Biol Fert Soils 44:965–973

de la Providencia IE, de Souza FA, Fernandez F, Delmas NS, Declerck S (2005) Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi reveal distinct patterns of anastomosis formation and hyphal healing mechanisms between different phylogenic groups. New Phytol 165:261–271

Duan TY, Facelli E, Smith SE, Smith FA, Nan ZB (2011) Differential effects of soil disturbance and plant residue retention on function of arbuscular mycorrhizal (AM) symbiosis are not reflected in colonization of roots or hyphal development in soil. Soil Biol Biochem 43:571–578

Eason WR, Newman EI (1990) Rapid cycling of nitrogen and phosphorus from dying roots of Lolium-perenne. Oecologia 82:432–436

Eissenstat DM (1990) A comparison of phosphorus and nitrogen transfer between plants of different phosphorus status. Oecologia 82:342–347

Evans DG, Miller MH (1988) Vesicular arbuscular mycorrhizas and the soil-disturbance-induced reduction of nutrient absorption in maize.1. Causal relations. New Phytol 110:67–74

Evans DG, Miller MH (1990) The role of the external mycelial network in the effect of soil disturbance upon vesicular arbuscular mycorrhizal colonization of maize. New Phytol 114:65–71

Frey B, Schüepp H (1993) Acquisition of nitrogen by external hyphae of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi associated with Zea mays L. New Phytol 124:221–230

Gericke S, Kurmies B (1952) Die kolorimetrische Phosphorsäurebestimmung mit Ammonium-Vanadat-Molybdat und ihre Anwendung in der Pflanzenanalyse. J Plant Nutr Soil Sci 159:11–21

Giovannetti M, Sbrana C, Avio L, Citernesi AS, Logi C (1993) Differential hyphal morphogenesis in arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi during preinfection stages. New Phytol 125:587–593

Govindarajulu M, Pfeffer PE, Jin HR, Abubaker J, Douds DD, Allen JW, Bucking H, Lammers PJ, Shachar-Hill Y (2005) Nitrogen transfer in the arbuscular mycorrhizal symbiosis. Nature 435:819–823

Grime JP, Mackey JML, Hillier SH, Read DJ (1987) Floristic diversity in a model system using experimental microcosms. Nature 328:420–422

Hamel C, Nesser C, Barrantescartin U, Smith DL (1991) Endomycorrhizal fungal species mediate N-15 transfer from soybean to maize in non-fumigated soil. Plant Soil 138:41–47

Hanssen JF, Thingstad TF, Goksoyr J (1974) Evaluation of hyphal lengths and fungal biomass in soil by a membrane-filter technique. Oikos 25:102–107

Hartnett DC, Hetrick BAD, Wilson GWT, Gibson DJ (1993) Mycorrhizal influence on intraspecific and interspecific neighbor interactions among co-occurring prairie grasses. J Ecol 81:787–795

Hawkins HJ, George E (2001) Reduced N-15-nitrogen transport through arbuscular mycorrhizal hyphae to Triticum aestivum L. supplied with ammonium vs. nitrate nutrition. Ann Bot-London 87:303–311

Hawkins HJ, Johansen A, George E (2000) Uptake and transport of organic and inorganic nitrogen by arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi. Plant Soil 226:275–285

Haystead A, Malajczuk N, Grove TS (1988) Underground transfer of nitrogen between pasture plants infected with vesicular arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi. New Phytol 108:417–423

Hodge A, Campbell CD, Fitter AH (2001) An arbuscular mycorrhizal fungus accelerates decomposition and acquires nitrogen directly from organic material. Nature 413:297–299

Ikram A, Jensen ES, Jakobsen I (1994) No significant transfer of N and P from Pueraria phaseoloides to Hevea brasiliensis via hyphal links of arbuscular mycorrhiza. Soil Biol Biochem 26:1541–1547

Jackson LE, Calderon FJ, Steenwerth KL, Scow KM, Rolston DE (2003) Responses of soil microbial processes and community structure to tillage events and implications for soil quality. Geoderma 114:305–317

Jalonen R, Nygren P, Sierra J (2009) Transfer of nitrogen from a tropical legume tree to an associated fodder grass via root exudation and common mycelial networks. Plant Cell Environ 32:1366–1376

Jansa J, Mozafar A, Frossard E (2005) Phosphorus acquisition strategies within arbuscular mycorrhizal fungal community of a single field site. Plant Soil 276:163–176

Jasper DA, Abbott LK, Robson AD (1989) Soil disturbance reduces the infectivity of external hyphae of vesicular arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi. New Phytol 112:93–99

Jasper DA, Abbott LK, Robson AD (1991) The effect of soil disturbance on vesicular arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi in soils from different vegetation types. New Phytol 118:471–476

Johansen A, Jensen ES (1996) Transfer of N and P from intact or decomposing roots of pea to barley interconnected by an arbuscular mycorrhizal fungus. Soil Biol Biochem 28:73–81

Johansen A, Jakobsen I, Jensen ES (1992) Hyphal transport of N-15-labeled nitrogen by a vesicular-arbuscular mycorrhizal fungus and its effect on depletion of inorganic soil-N. New Phytol 122:281–288

Johansen A, Jakobsen I, Jensen ES (1994) Hyphal N transport by a vesicular-arbuscular mycorrhizal fungus associated with cucumber grown at 3 nitrogen levels. Plant Soil 160:1–9

Koske RE, Gemma JN (1989) A Modified procedure for staining roots to detect VA-Mycorrhizas. Mycol Res 92:486–505

Li YF, Ran W, Zhang RP, Sun SB, Xu GH (2009) Facilitated legume nodulation, phosphate uptake and nitrogen transfer by arbuscular inoculation in an upland rice and mung bean intercropping system. Plant Soil 315:285–296

Mäder P, Vierheilig H, Streitwolf-Engel R, Boller T, Frey B, Christie P, Wiemken A (2000) Transport of N-15 from a soil compartment separated by a polytetrafluoroethylene membrane to plant roots via the hyphae of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi. New Phytol 146:155–161

McGonigle TP, Miller MH (2000) The inconsistent effect of soil disturbance on colonization of roots by arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi: a test of the inoculum density hypothesis. Appl Soil Ecol 14:147–155

McGonigle TP, Evans DG, Miller MH (1990) Effect of degree of soil disturbance on mycorrhizal colonization and phosphorus absorption by maize in growth chamber and field experiments. New Phytol 116:629–636

Mikkelsen BL, Rosendahl S, Jakobsen I (2008) Underground resource allocation between individual networks of mycorrhizal fungi. New Phytol 180:890–898

Nett L, Averesch S, Ruppel S, Ruhlmann J, Feller C, George E, Fink M (2010) Does long-term farmyard manure fertilization affect short-term nitrogen mineralization from farmyard manure? Biol Fert Soils 46:159–167

Neumann E, George E (2005) Does the presence of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi influence growth and nutrient uptake of a wild-type tomato cultivar and a mycorrhiza-defective mutant, cultivated with roots sharing the same soil volume? New Phytol 166:601–609

Ritz K, Newman EI (1985) Evidence for rapid cycling of phosphorus from dying roots to living plants. Oikos 45:174–180

Schüller H (1969) Die CAL-Methode, eine neue Methode zur Bestimmung des pflanzenverfügbaren Phosphates in Böden. J Plant Nutr Soil Sci 123:48-63

Smit AL, Bengough AG, Engels C, van Noordwijk M, Pellerin S, van de Geijn SC (2000) Root methods: a handbook. Springer, Berlin

Smith SE, Smith FA, Jakobsen I (2004) Functional diversity in arbuscular mycorrhizal (AM) symbioses: the contribution of the mycorrhizal P uptake pathway is not correlated with mycorrhizal responses in growth or total P uptake. New Phytol 162:511–524

Subramanian KS, Charest C (1999) Acquisition of N by external hyphae of an arbuscular mycorrhizal fungus and its impact on physiological responses in maize under drought-stressed and well-watered conditions. Mycorrhiza 9:69–75

Tennant D (1975) A test of a modified line intersect method of estimating root length. J Ecol 63:995–1001

Tian CJ, Kasiborski B, Koul R, Lammers PJ, Bucking H, Shachar-Hill Y (2010) Regulation of the nitrogen transfer pathway in the arbuscular mycorrhizal symbiosis: Gene characterization and the coordination of expression with nitrogen flux. Plant Physiol 153:1175–1187

Tobar RM, Azcon R, Barea JM (1994) The improvement of plant N acquisition from an ammonium-treated, drought-stressed soil by the fungal symbiont in arbuscular mycorrhizae. Mycorrhiza 4:105–108

Tuffen F, Eason WR, Scullion J (2002) The effect of earthworms and arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi on growth of and P-32 transfer between Allium porrum plants. Soil Biol Biochem 34:1027–1036

van Aarle IM, Olsson PA (2003) Fungal lipid accumulation and development of mycelial structures by two arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi. Appl Environ Microb 69:6762–6767

van der Krift TAJ, Gioacchini P, Kuikman PJ, Berendse F (2001) Effects of high and low fertility plant species on dead root decomposition and nitrogen mineralisation. Soil Biol Biochem 33:2115–2124

Walter LEF, Hartnett DC, Hetrick BAD, Schwab AP (1996) Interspecific nutrient transfer in a tallgrass prairie plant community. Am J Bot 83:180–184

Wichern F, Mayer J, Joergensen RG, Muller T (2007) Release of C and N from roots of peas and oats and their availability to soil microorganisms. Soil Biol Biochem 39:2829–2839

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Susan Barker from the University of Western Australia for the permission to use the rmc mutant tomato seeds. We also thank the Leibniz Association and the German Federal Ministries BMELV, MIL and TMNLU for financing the MycoPakt Project. We are very grateful to the reviewers of Plant and Soil for their constructive comments and criticisms. Thanks also go to Robert Koebner (Norwich, UK) for his editorial work on this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Responsible Editor: Hans Lambers.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Table S1

Nutrient contents of donor plant roots from the donor compartment (DC). Mean values ± SD shown for wild type [WT] or mycorrhiza-defective [rmc] mutant tomato plants, either inoculated [+AM] or non-inoculated [-AM] with Glomus intraradices. The donor shoots were removed at the end of the labelling period and the substrate in the donor root compartment was either left undisturbed [U], or was manually disrupted [X]. Within each row, means followed by a different letter differ significantly from another according to a multiple comparison Tukey-test (p < 0.05) (DOC 34 kb)

Table S2

Three-way ANOVA for donor plants (for data, see Table S1). P and F values are shown for the main effects of inoculation with AMF (M), donor genotype (G), and donor substrate treatment (S). Values in bold indicate significant differences (p < 0.05) (DOC 32 kb)

Table S3

Receiver plant nutrient contents. Receiver plants were cultivated with their root system adjacent to that of either a wild type [WT] donor or a mycorrhiza-defective [rmc] tomato mutant. Both, the donor and receiver plant was either inoculated [+AM] or non-inoculated [-AM] with G. intraradices. The donor plant shoots were removed at the end of the labelling period and the substrate in the donor root compartment was either left undisturbed [U], or was manually disrupted [X]. Within each row, means followed by a different letter significantly differ from another according to a multiple comparison Tukey-test (p < 0.05) (DOC 37 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 International License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Müller, A., George, E. & Gabriel-Neumann, E. The symbiotic recapture of nitrogen from dead mycorrhizal and non-mycorrhizal roots of tomato plants. Plant Soil 364, 341–355 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11104-012-1372-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11104-012-1372-7