Abstract

Background

Routine utilization of evidence-based clinical practice guidelines (CPGs) is an effective strategy to optimize patient care and reduce practice variation. Healthcare professionals’ failure to adhere to CPGs introduces risks to both patients and the sustainability of healthcare systems. The integration of theory to investigate adherence provides greater insight into the often complex reasons for suboptimal behaviors.

Aim

To determine the coverage of literature surrounding the use of theory in studies of CPG adherence, report the key findings and identify the knowledge gaps.

Method

In April 2021, three bibliographic databases were searched for studies published since January 2010, adopting theory to investigate health professionals’ adherence to CPGs. Two reviewers independently screened the articles for eligibility and charted the data. A narrative approach to synthesis was employed.

Results

The review includes 12 articles. Studies were limited to primarily investigations of physicians, quantitative designs, single disease states and few countries. The use of behavioral theories facilitated pooling of data of barriers and facilitators of adherence. The domains and constructs of a number of the reported theories are captured within the Theoretical Domains Framework (TDF); the most common barriers aligned with the TDF domain of environmental context and resources, fewer studies reported facilitators.

Conclusion

There is emerging use of behavioral theories investigating physicians’ adherence to CPGs. Although limited in number, these studies present specific insight into common barriers and facilitators, thus providing valuable evidence for refining existing and future implementation strategies. Similar investigations of other health professionals are warranted.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Impact Statements

-

Investigations underpinned with behavioural theory provide more robust and generalizable evidence of healthcare professionals’ failure to adhere to Clinical Practice Guidelines, such data is essential to inform the refinement of existing and future implementation strategies.

-

The domains and constructs of a number of the reported theories are captured within the Theoretical Domains Framework, thus demonstrating its versatility and advantage for such studies.

-

Further investigations of physicians in alternative settings and of other health professionals are warranted to confirm the generalizability and the association of the existing literature.

Introduction

Healthcare systems continuously seek strategies to enhance the quality of service delivery through promoting evidence-based practice and addressing inefficiencies. The implementation and routine utilization of clinical practice guidelines (CPGs) has long since been proposed to be an effective strategy to optimize patient care and reduce practice variation [1]. Equally, there is established consensus within the literature that failure to systematically develop, implement, and adhere to CPGs introduces risks to both patients and the sustainability of healthcare systems [1, 2].

For example, implementation investigations, which refers to the extent to which efficacious health interventions, such as CPGs, are effectively integrated into real-world clinical service systems [3]; have revealed the influence of numerous multilevel (patient, provider, team, organization system), often competing, factors that makes implementation of clinical guidelines complex and challenging[4,5,6]. Similarly adherence, which refers to the degree in which one’s behaviour coincides with recommendations [7], such as those included in CPGs, has been widely investigated, reporting a multitude of reasons for non-adherence to CPGs (e.g. patient preference, contra-indications, lack of knowledge) and its potential to result in suboptimal healthcare delivery and inefficiencies[1, 8,9,10].

The definition of CPGs most frequently cited is that of Field and Lohr, “systematically developed statements to assist practitioner and patient decisions about appropriate health care for specific clinical circumstances” [11]. Since the 1980s, there has been a rapid increase in the number and scope of CPGs; subsequent studies have reported their outcomes. Systematic reviews focusing on numerous clinical areas have reported improved patient health outcomes, reduced admission rates and length of hospital stay, less resource utilization and decreased medical costs [12,13,14,15,16,17,18]

However, the development of CPGs is complex and not without its challenges. Panel composition influencing recommendations; multiple scoring systems for the quality of evidence and ‘grades of recommendations’ and the limitations thereof; and timely guideline updating are but a few of the issues that warrant significant consideration in order to develop credible CPGs and necessitate appropriate critical appraisal skills of clinicians in order to advantage from them [19]. Furthermore, the rapid increase in the number of CPGs produced by different organizations on the same or similar topics, which can either agree or disagree with each other, can generate uncertainty in clinicians and patients about optimal recommendations, and instill doubt in the process of CPG development [20, 21]. Thus, for CPGs to benefit outcomes, specific attention is required to the processes of their dissemination, implementation and adherence. Indeed, there is an increasing body of literature reporting on the effectiveness of interventions to improve these processes and thereby enhance the routine use of CPGs in clinical settings. Relevant systematic reviews have focused on investigating interventions to uptake CPGs or best practices that target specific clinicians, including physicians [22,23,24,25], nurses [26,27,28,29] and allied health professionals [30,31,32,33]. These reviews have reported mixed outcomes, with only two conclusively reporting a positive improvement on professional outcomes such as knowledge and practice behaviors [31, 32].

Eccles et al. propose that adopting theory in such investigations provides further valuable insight on how determinants (e.g. physician attitude) influence the association between processes and outcomes, and facilitates more detailed understanding of strategies that may mitigate against determinants to support processes associated with desirable outcomes [34]. One subsequent scoping review sought to investigate how theory (including models and frameworks) had been employed to plan or evaluate the implementation and use of guidelines among physicians [35]. The review revealed that a range of theories (or models/frameworks) have been utilized in different aspects of individual study designs, and positive outcomes were achieved only in the few studies that had applied theory to evaluate interventions. The review also concluded that reported studies did not explicitly link pre-identified determinants of guideline use to specific theoretical constructs; and subsequently recommended further research to establish the number of types of theories that result in improved guideline use to help understand why theory-informed interventions fail to consistently achieve desired outcomes [35].

Similarly a systematic review by Davies et al. on studies evaluating guideline dissemination or implementation strategy targeting physicians concluded greater use of explicit theory, specifically behavioral change theories, is required to understand barriers, design interventions, and explore mediating pathways and moderators [36]. These theories intend to provide greater insight into the often complex reasons for suboptimal behaviors [37, 38]

Such recommendations are closely aligned to those of the United Kingdom (UK) Medical Research Council (MRC) guidance on ‘Developing and implementing complex interventions’, which attributes theory a central role within the process [37].

While reviews have focused on the stage of implementation of CPGs and the use of theory, none have reported the key process of adherence.

Aim

The aims of this scoping review were to determine the coverage of literature surrounding the use of theory in studies of CPG adherence, report the key findings and identify the knowledge gaps.

Method

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) checklist guided the conduct and reporting of this review [39, 40].

Inclusion criteria

Studies reporting any health professional practicing in any setting which applied any theory or theoretical framework to study adherence to clinical guidelines were included in the review; this included both interventional and non-interventional studies. Studies which focused on implementation were excluded. The search included peer-reviewed studies published in English from January 2010 until April 2021 were included; editorials, commentaries, abstracts and letters were excluded.

Search strategy

The search was conducted in PubMed, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) and Scopus. References lists of included articles were reviewed for inclusion. The following Medical Subject Headings [MeSH] and keywords were adapted to each database using ‘OR’: "theor*", "framework(s)". These were combined with "guideline(s) using ‘AND’. The results from this search were combined with the following using ‘AND’: "health personnel", "clinician(s)", “delivery of health care", "practitioner(s)".

All articles were exported to the support platform for the development of systematic reviews Rayyan QCRI® [41], and duplicates were removed. Two reviewers independently screened titles and abstracts followed by full text for eligibility, with disagreements resolved by discussion or consultation with a third reviewer.

Data extraction

Data were independently extracted by two reviewers using a standardized pilot data collection tool. The following data were extracted: study aim; setting, study design; simple size; health professionals studied; and the theory or theoretical framework used.

Synthesis

A narrative approach to data synthesis was employed to pool the evidence on how the theories and theoretical frameworks were used, and the main findings in relation to the aim around clinical guideline adherence. These findings were mapped to key behavioural determinants of adherence.

Results

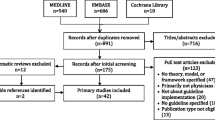

A total of 8679 studies were identified from the search, with 6364 remaining following removal of duplicates. Review of titles and abstracts resulted in 71 full-text studies being screened and 12 retained for data extraction and synthesis (Table 1). The main reason for exclusion at full-text review was the study outcomes of implementation and not adherence (n = 38) (see Fig. 1).

Study characteristics

Table 2 gives the study characteristics. Studies were conducted in the United States (US) [42,43,44], Palestine [45,46,47], the Netherlands [48, 49], Belgium [50], Canada/US [51], Cyprus [52] and the United Kingdom [53]. The most common methodology was a cross-sectional survey [42,43,44,45,46, 48, 50], with the questionnaires used in two studies being informed by prior qualitative research [48, 50]. Survey participant numbers ranged from 133 to 264 [42, 48], with response rates of 38.0% to 93.3% [45, 46, 48]. Participants were largely physicians, with a smaller number of nurses, representing hospitals and family medicine facilities. Five qualitative studies were reported, two of which employed focus groups [51, 52], two semi-structured interviews [47, 49], and one a combination of focus groups and semi-structured interviews [53]. A total of 126 individuals participated in the qualitative studies, ranging from 16 to 43 comprising physicians, nurses, chiropractors and health care assistants, representing hospitals, family medicine facilities and research centres.

Study aims

Study aims focused on issues of adherence and associated beliefs, and perceptions of barriers and facilitators relating to an array of clinical guidelines. The guidelines largely focused on single disease states or therapeutics issues, specifically diabetes mellitus in four studies [43, 45,46,47], and one study each for antimicrobials [50], cystic fibrosis [42], dental referral [44], exposure to microorganisms [52], smoking cessation [49], spine disorders [51] and suspected encephalitis [53]. One study targeted four different guidelines (red eye, cerebrovascular accident, urinary tract infection and thyroid disorders) [48].

Theories and theoretical frameworks used

Table 2 summarizes the theories and theoretical frameworks used, the rationale for use provided by the authors, how they were used, and the main findings. All are related to aspects of behavior and behavior change. The Cabana Framework was the most frequently used [42, 44, 45, 47, 48], followed by the Theoretical Domains Framework (TDF) [51, 53], the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) [50], Competing Value Framework [46], and the Health Belief Model (HBM) [52]. Two studies utilized a combination of theories; I-Change Model and the Diffusion of Innovations Theory [49], TPB and Theory of Work Adjustment (TWA) [43].

The domains or constructs of the theories and theoretical frameworks are illustrated in Supplementary File 1.

Theories and frameworks were largely justified in terms of the underlying domains and constructs in relation to the study aims. Other reasons included the tradition of using a particular theory or framework in studying particular behaviors or in specific clinical settings. For example, Backman et al. reported that TDF had been applied in a variety of settings and studies of clinical behaviors [53]. Cartoos et al. noted that the Theory of Planned Behavior had been used effectively in the evaluation of medical practice, including antibiotic use [50]. No justification was provided in two studies [44, 48], both of which used the Cabana Framework. Questionnaires were derived with reference to the theories and theoretical frameworks in the cross-sectional surveys; these aided the development of data generation tools and analytical coding frameworks in the qualitative studies.

Main findings in relation to the aims

The use of behavioral theories and theoretical frameworks facilitated pooling of data of barriers and facilitators of adherence. In addition, the domains and constructs of a number of the behavioral theories (e.g., TPB, HBM) are captured within TDF. Almost all studies reported barriers to adherence, the most common aligning with the TDF domain of environmental context and resources. Participants reported several related factors limiting adherence, including busy schedules [42, 44, 45, 47, 52, 53], guidelines being outdated or a perceived lack of trustworthiness in the recommendations [45, 47, 49], practising according to the guidelines considered burdensome [42, 52], lack of specific resources [45, 47, 53] and insufficient training [49]. There were also issues relating to knowledge of the existence of guidelines and their content [42, 44, 48, 51, 53]. Several studies reported barriers aligning to the belief of consequences domain. There were reports of concern that adhering to the guidelines would deliver the clinical gains claimed [1, 2, 4, 11]. There were also issues of belief of capabilities in being able to apply the guideline recommendations [49][1, 2, 4, 7]. TDF domains which emerged less commonly were those relating to social influences, including other health professionals not adhering [4] and pressure from patients not to adhere [6]. Two studies reported the issues of behavioral regulation, notably the lack of incentives to adhere [9, 10]. Memory, attention and decision making was noted to be an issue in one study, specifically remembering to apply the guideline [1].

Fewer studies reported facilitators to guideline adherence. These included belief of consequences of the clinical gain to be achieved [4] and cost savings [5]. Participants in one study cited guideline adherence to be part of their professional role and identity [12], while others noted constant reminders as a positive influence [4].

Discussion

The key finding of this scoping review is that a limited number of studies have applied any theory to explore health professionals’ adherence to CPGs. Use of TDF (or individual behavioural theories integral to TDF) identified barriers to adherence relating to the environmental context and resources, beliefs of consequences, beliefs of capabilities and aspects of knowledge. Few studies reported any facilitators to adherence.

This scoping review was conducted according to best practice through the application of rigorous and transparent processes [39, 40]. Munn et al. suggest that scoping reviews are particularly appropriate for reporting the coverage of literature and examining evidence when it is uncertain if more specific questions can be answered through conducting a systematic review [54]. One further key difference compared to a systematic review is the absence of quality assessment of included studies. Limitations of the review are the index search date of 2010 and restricting the search to CPGs. It is likely that extending the review to other forms of guidelines would have captured a greater body of work. Furthermore, it is conceivable that the related concepts of adoption and implementation are reported on in the literature without clear distinction; further complexity may be added by the variation in terminology and classification of terms across countries. Indeed, a review of research funding agencies in nine countries revealed 29 distinct terms referring to aspects of dissemination and implementation research [55].

This scoping review has identified a paucity of theory informed studies, with only 12 identified from seven countries, which contrasts with the vast number of systematic and scoping reviews on the wider literature of health professionals’ adherence to CPGs. There is therefore a clear gap in the literature in terms of the number and coverage of studies. This gap is reinforced given that most studies were cross-sectional surveys with less qualitative studies and no mixed methods studies. The lack of studies must be borne in mind when interpreting the findings.

Theories were largely used to develop data collection tools and analytical frameworks, with the most common being the Cabana Framework and TDF. TDF is an integrative framework of 33 behaviour change theories and 128 theoretical constructs, described in 14 overarching domains [56, 57]. Of note, three further studies used the HBM, TPB and Diffusion of Innovations, which are included in the 33 theories captured in TDF. While there is some similarity between the theories identified in the scoping review of implementation studies by Liang et al. [35], it must be acknowledged that implementation and adherence are very different, albeit related processes. Implementation studies are more likely to apply implementation theories and frameworks, such as the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) [58], rather than adherence studies which are more likely to focus on behavior change theories and frameworks such as TDF.

There are a number of benefits to applying theory, including enhancing the robustness and rigour, and the relevance and impact of research findings. Theories provide comprehensive explanations, e.g., the 14 domains TDF represent the determinants of (influences on) any behaviour which may be facilitators, barriers, or have no or little influence. Using theory enables researchers to connect pieces of research data to generate findings which fit into a collation of other studies [59]. The robust and rigorous evidence of behavioural determinants can aid the development of targeted interventions, which are more likely to be effective and sustained rather than those developed more pragmatically. The UK Medical Research Council guidance, ‘Developing and implementing complex interventions’ [60], emphasizes the importance of theory in the development stage. ‘Complex interventions’ are essential those with multiple interacting components and players, which aligns to the processes and number of potentially influences on CPG adherence.

Key barriers to adherence were TDF domains of environmental context and resources (e.g., outdated guidelines, burdensome guidelines, lack of resources), belief of consequences (e.g., adhering would not deliver clinical gains claimed), belief of capabilities (e.g., ability to apply CPGs) and knowledge (e.g., existence of CPGs). Those studies which used the Cabana Framework identified similar issues. These barriers can act as behaviour change intervention (BCI) targets, defined as `coordinated sets of activities designed to change specified behaviour patterns'. BCIs consist of interacting components known as `behaviour change techniques' (BCTs) which are `observable and replicable components designed to change behaviour' [61, 62]. Evidence based BCTs are mapped to specific TDF domains to facilitate intervention development [56, 57]. For example, BCTs mapped to beliefs of consequences include: anticipated regret (inducing or raising awareness of expectations of future regret); and comparative imaging of future outcomes (prompt or advise the imagining and comparing of future outcomes). These BCTs would form the basis of interventions which would be tested through the stages of feasibility and pilot testing, evaluation and implementation in future studies. There may be merit in conducting a systematic review to systematically review, critically appraise and synthesize the evidence on the application and use of theory in the development and evaluation of behaviour change interventions designed to improve health professionals’ adherence to CPGs. The Theory Coding Scheme (TCS) would aid assessment of the specific ways in which theory had been applied. Consisting of 19 items, provides a detailed and comprehensive checklist for assessing the extent to which behaviour change interventions are theoretically based [63]. One potential limitation to this systematic review would be the likely small number of relevant studies.

Conclusion

There is emerging use of behavioural theories investigating physicians’ adherence to CPGs; notably the domains and constructs of a number of the reported theories are captured within the TDF. Although limited in number, these studies present specific insight into the barriers, which align to the environmental context and resources TDF domain, and less frequently the facilitators of physicians’ adherence to CPGs. This data provide valuable evidence for refining existing and the development of future implementation strategies. Similar investigations of physicians in alternative settings and of other health professionals are warranted to confirm the generalizability and the association of these findings.

References

Woolf SH, Grol R, Hutchinson A, et al. Potential benefits, limitations, and harms of clinical guidelines. BMJ. 1999;318(7182):527–30.

Mackey TK, Liang BA. The role of practice guidelines in medical malpractice litigation. AMA J Ethics. 2011;13(1):36–41.

Spiegelman D. Evaluating public health interventions: 1. Examples, definitions, and a personal note. Am J Public Health. 2016;106(1):70–3.

Flottorp SA, Oxman AD, Krause J, et al. A checklist for identifying determinants of practice: a systematic review and synthesis of frameworks and taxonomies of factors that prevent or enable improvements in healthcare professional practice. Implement Sci. 2013;8(1):1–11.

Sheldon TA, Cullum N, Dawson D, et al. What's the evidence that NICE guidance has been implemented? Results from a national evaluation using time series analysis, audit of patients' notes, and interviews, British Medical Journal Publishing Group; 2004.

McGlynn EA, Asch SM, Adams J, et al. The quality of health care delivered to adults in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(26):2635–45.

Gardner CL. Adherence: a concept analysis. Int J Nurs Knowl. 2015;26(2):96–101.

Grol R. Personal paper: beliefs and evidence in changing clinical practice. BMJ. 1997;315(7105):418–21.

Grol R, Grimshaw J. From best evidence to best practice: effective implementation of change in patients’ care. Lancet. 2003;362(9391):1225–30.

Cabana MD, Rand CS, Powe NR, et al. Why don’t physicians follow clinical practice guidelines? A framework for improvement. JAMA. 1999;282(15):1458–65.

Field MJ, Lohr KN. Clinical practice guidelines. In: Directions for a new program, 1990;pp. 1990.

Bahtsevani C, Udén G, Willman A. Outcomes of evidence-based clinical practice guidelines: a systematic review. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2004;20(4):427–33.

Pérez-Panero AJ, Ruiz-Muñoz M, Cuesta-Vargas AI, et al. Prevention, assessment, diagnosis and management of diabetic foot based on clinical practice guidelines: a systematic review. Medicine, 2019; 98(35).

Nguyen T, Seiler N, Brown E, et al. The effect of Clinical Practice Guidelines on prescribing practice in mental health: a systematic review. Psychiatry Res. 2020;284: 112671.

Meriwether KV, Antosh DD, Olivera CK, et al. Uterine preservation vs hysterectomy in pelvic organ prolapse surgery: a systematic review with meta-analysis and clinical practice guidelines. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018;219(2):129-146,e2.

Tomaschek R, Gemperli A, Rupp R, et al. A systematic review of outcome measures in initial rehabilitation of individuals with newly acquired spinal cord injury: providing evidence for clinical practice guidelines. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med. 2019;55(5):605–17.

Abboud J, Abdel Rahman A, Kahale L, et al. Prevention of health care associated venous thromboembolism through implementing VTE prevention clinical practice guidelines in hospitalized medical patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Implement Sci. 2020;15(1):1–11.

Mammen MJ, Pai V, Aaron SD, et al. Dual LABA/LAMA therapy versus LABA or LAMA monotherapy for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis in support of the American Thoracic Society clinical practice guideline. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2020;17(9):1133–43.

Browman GP. Evidence-based clinical practice guideline development: principles, challenges, and accountability to evidence. J Surg Oncol. 2010;101:1–2.

Birch S, Alraek T, Lee MS. Challenges for clinical practice guidelines in traditional medicines: the example of acupuncture. Eur J Integr Med. 2016;8(4):332–6.

Franco JVA, Arancibia M, Meza N, et al. Clinical practice guidelines: concepts, limitations and challenges. Medwave, 2020; 20(3).

Flodgren G, Eccles MP, Shepperd S, et al. An overview of reviews evaluating the effectiveness of financial incentives in changing healthcare professional behaviours and patient outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev; 2011(7).

Vergouwen AC, Bakker A, Katon WJ, et al. Improving adherence to antidepressants: a systematic review of interventions. J Clin Psychiatry. 2003;64(12):8795.

Williams JW Jr, Gerrity M, Holsinger T, et al. Systematic review of multifaceted interventions to improve depression care. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2007;29(2):91–116.

Kawamoto K, Lobach DF. Clinical decision support provided within physician order entry systems: a systematic review of features effective for changing clinician behavior. In: AMIA Annual Symposium Proceedings; 2003. American Medical Informatics Association.

Robinson JD, Segal R, Lopez LM, et al. Impact of a pharmaceutical care intervention on blood pressure control in a chain pharmacy practice. Ann Pharmacother. 2010;44(1):88–96.

Thompson DS, Estabrooks CA, Scott-Findlay S, et al. Interventions aimed at increasing research use in nursing: a systematic review. Implement Sci. 2007;2(1):1–16.

Thompson C, Stapley S. Do educational interventions improve nurses’ clinical decision making and judgement? A systematic review. Int J Nurs Stud. 2011;48(7):881–93.

Foxcroft D, Cole N. Organisational infrastructures to promote evidence based nursing practice. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2000. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD002212.

Scott SD, Albrecht L, O’Leary K, et al. Systematic review of knowledge translation strategies in the allied health professions. Implement Sci. 2012;7(1):1–17.

Menon A, Korner-Bitensky N, Kastner M, et al. Strategies for rehabilitation professionals to move evidence-based knowledge into practice: a systematic review. In: Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE): Quality-assessed Review; 2009.

van der Wees PJ, Jamtvedt G, Rebbeck T, et al. Multifaceted strategies may increase implementation of physiotherapy clinical guidelines: a systematic review. Aust J Physiother. 2008;54(4):233–41.

Bérubé M-È, Bastien M, Laliberté L-A, et al. Strategies to translate knowledge related to common musculoskeletal conditions into physiotherapy practice: a systematic review. Physiotherapy. 2018;104(1):1–8.

Eccles M, Grimshaw J, Walker A, et al. Changing the behavior of healthcare professionals: the use of theory in promoting the uptake of research findings. J Clin Epidemiol. 2005;58(2):107–12.

Liang L, Bernhardsson S, Vernooij RW, et al. Use of theory to plan or evaluate guideline implementation among physicians: a scoping review. Implement Sci. 2017;12(1):1–12.

Davies P, Walker AE, Grimshaw JM. A systematic review of the use of theory in the design of guideline dissemination and implementation strategies and interpretation of the results of rigorous evaluations. Implement Sci. 2010;5(1):1–6.

Skivington K, Matthews L, Simpson SA, et al. A new framework for developing and evaluating complex interventions: update of Medical Research Council guidance. BMJ, 2021; 374

Michie S, Van Stralen MM, West R. The behaviour change wheel: a new method for characterising and designing behaviour change interventions. Implement Sci. 2011;6(1):1–12.

Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(7):467–73.

McGowan J, Straus S, Moher D, et al. Reporting scoping reviews—PRISMA ScR extension. J Clin Epidemiol. 2020;123:177–9.

Ouzzani M, Hammady H, Fedorowicz Z, et al. Rayyan—a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst Rev. 2016;5(1):1–10.

Glauser T, Nevins P, Williamson J, et al. Adherence to the 2007 cystic fibrosis pulmonary guidelines: a national survey of CF care centers. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2012;47(5):434–40.

Waddimba AC, Beckman HB, Mahoney TL, et al. The moderating effect of job satisfaction on physicians’ motivation to adhere to financially incentivized clinical practice guidelines. Med Care Res Rev. 2017;74(2):148–77.

Zhu Y, Close K, Zeldin L, et al. A clinical vignette-based study of physicians’ adherence to guidelines for dental referrals of young children. Acad Pediatr. 2019;19(2):195–202.

Radwan M, Akbari Sari A, Rashidian A, et al. Attitudes of Palestinian health-care professionals in Gaza to clinical practice guideline for diagnosis and treatment of diabetes mellitus. Front Endocrinol. 2017;8:288.

Radwan M, Akbari Sari A, Rashidian A, et al. Influence of organizational culture on provider adherence to the diabetic clinical practice guideline: using the competing values framework in Palestinian Primary Healthcare Centers. Int J Gen Med. 2017;10:239.

Radwan M, Akbari Sari A, Rashidian A, et al. Factors hindering the adherence to clinical practice guideline for diabetes mellitus in the Palestinian primary healthcare clinics: a qualitative study. BMJ Open. 2018;8(9):e021195.

Lugtenberg M, Burgers JS, Besters CF, et al. Perceived barriers to guideline adherence: a survey among general practitioners. BMC Fam Pract. 2011;12(1):1–9.

De Ruijter D, Smit E, De Vries H, et al. Understanding Dutch practice nurses’ adherence to evidence-based smoking cessation guidelines and their needs for web-based adherence support: results from semistructured interviews. BMJ Open. 2017;7(3):e014154.

Cortoos P-J, Schreurs BH, Peetermans WE, et al. Divergent intentions to use antibiotic guidelines: a theory of planned behavior survey. Med Decis Making. 2012;32(1):145–53.

Bussières AE, Patey AM, Francis JJ, et al. Identifying factors likely to influence compliance with diagnostic imaging guideline recommendations for spine disorders among chiropractors in North America: a focus group study using the theoretical domains framework. Implement Sci. 2012;7(1):1–11.

Efstathiou G, Papastavrou E, Raftopoulos V, et al. Factors influencing nurses’ compliance with Standard Precautions in order to avoid occupational exposure to microorganisms: a focus group study. BMC Nurs. 2011;10(1):1–12.

Backman R, Foy R, Michael BD, et al. The development of an intervention to promote adherence to national guidelines for suspected viral encephalitis. Implement Sci. 2015;10(1):1–12.

Munn Z, Peters MD, Stern C, et al. Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2018;18(1):1–7.

Green LW. From research to “best practices” in other settings and populations. Am J Health Behav. 2001;25(3):165–78.

Cane J, O’Connor D, Michie S. Validation of the theoretical domains framework for use in behaviour change and implementation research. Implement Sci. 2012;7(1):1–17.

Michie S, Johnston M, Abraham C, et al. Making psychological theory useful for implementing evidence based practice: a consensus approach. BMJ Qual Saf. 2005;14(1):26–33.

Damschroder LJ, Aron DC, Keith RE, et al. Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: a consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implement Sci. 2009;4(1):1–15.

Stewart D, Klein S. The use of theory in research. Int J Clin Pharm. 2016;38(3):615–9.

Barnett-Itzhaki Z, Berman T, Grotto I, et al. Household medical waste disposal policy in Israel. Isr J Health Policy Res. 2016;5(1):48.

Michie S, Richardson M, Johnston M, et al. The behavior change technique taxonomy (v1) of 93 hierarchically clustered techniques: building an international consensus for the reporting of behavior change interventions. Ann Behav Med. 2013;46(1):81–95.

Michie S, Wood CE, Johnston M, et al. Behaviour change techniques: the development and evaluation of a taxonomic method for reporting and describing behaviour change interventions (a suite of five studies involving consensus methods, randomised controlled trials and analysis of qualitative data). Health Technol Assess, 2015. 19(99).

Michie S, Prestwich A. Are interventions theory-based? Development of a theory coding scheme. Health Psychol. 2010;29(1):1.

Funding

Open Access funding provided by the Qatar National Library. No funds were sourced to conduct this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

Derek Stewart is Editor-in-Chief and Yolande Hanssens Associate Editor of the International Journal of Clinical Pharmacy. They had no role in handling the manuscript, specifically the processes of editorial review, peer review and decision making.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Stewart, D., Al Hail, M., Al-Shaibi, S. et al. A scoping review of theories used to investigate clinician adherence to clinical practice guidelines. Int J Clin Pharm 45, 52–63 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11096-022-01490-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11096-022-01490-9