Abstract

The grain aphid Sitobion avenae (F.) is a major pest of wheat, acting as a virus vector as well as causing direct plant damage. Commonly grown wheat varieties in the UK have only limited resistance to this pest. The present study was carried out to investigate the potential of a diploid wheat line (ACC20 PGR1755), reported as exhibiting resistance to S. avenae, to serve as a source of resistance genes. The diploid wheat line was confirmed as partially resistant, substantially reducing the fecundity, longevity and growth rate of the aphid. Proteomic analysis showed that approximately 200 protein spots were reproducibly detected in leaf extracts from both the resistant line and a comparable susceptible line (ACC5 PGR1735) using two-dimensional gel electrophoresis and image comparison software. Twenty-four spots were significantly up-regulated (>2-fold) in the resistant line after 24 h of aphid feeding (13 and 11 involved in local and systemic responses, respectively). Approximately 50 % of all differentially expressed protein spots were identified by a combination of database searching with MS and MS/MS data, revealing that the majority of proteins up-regulated by aphid infestation were involved in metabolic processes (including photosynthesis) and transcriptional regulation. However, in the resistant line only, several stress response proteins (including NBS–LRR-like proteins) and oxidative stress response proteins were identified as up-regulated in response to aphid feeding, as well as proteins involved in DNA synthesis/replication/repair. This study indicates that the resistant diploid line ACC20 PGR1755 may provide a valuable resource in breeding wheat for resistance to aphids.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Wheat, Triticum aestivum L., is currently second to rice as the main human food crop and is the leading source of vegetable protein in human nutrition (United Nations 2012). Aphids (Order Hemiptera) are major insect pests of world agriculture, damaging crops by removing photoassimilates and vectoring numerous plant viruses (Smith and Boyko 2007). The grain aphid, Sitobion avenae (Fabricius), is considered a serious pest of commercial wheat in the UK. Many aphid species have evolved resistance to insecticides (Devonshire and Field 1991), and restrictions on the availability of active ingredients for insecticide production in Europe (European Directives 91/414/EEC) have prioritised research on crop varieties with resistance to aphid pests (Smith 2005). Most commercial wheat varieties have very little resistance to aphid pests (Migui 2002; Migui and Lamb 2003), with at best partial antibiosis, antixenosis and tolerance in some winter varieties (Havlícková 1993). However, recently a synthetic wheat line (98-10-35) with moderate levels of resistance to the grain aphid has been developed, although the mechanism of this constitutive resistance to S. avenae is not known (Wang et al. 2013).

Aphids differ from many other pest insects in their mode of feeding in that they do not cause major tissue damage or induce plant wounding responses (Farmer and Ryan 1992; Gatehouse 2002) since they feed from plant phloem by inserting a stylet between the cells. As a result, plant responses to aphid feeding have been reported to be similar to those induced by pathogen attack and, in some cases, have been classified as gene-for-gene interactions characteristic of plant–pathogen interactions (Walling 2000; Moran and Thompson 2001; Moran et al. 2002; Smith and Boyko 2007). This response has been reported to be induced by aphid-derived elicitors with salicylic acid (SA) as the major signalling molecule (Walling 2000; Moran et al. 2002; Smith and Boyko 2007). However, aphids can also induce a non-specific defence response in the plant, resulting in a general stress response, which can be detected in both aphid-resistant and aphid-susceptible plants (Smith and Boyko 2007). Plants experience extensive transcriptome reprogramming when they are subjected to insect attack (Moran and Thompson 2001; Zhang et al. 2004; De Vos et al. 2005; Yuan et al. 2005; Wei et al. 2009). Ferry et al. (2011) demonstrated that the proteome of wheat, variety ‘Claire’ a commercial winter wheat cultivar commonly grown in the UK, changed following aphid infestation. These changes were more consistent with SA-induced responses than the jasmonic acid (JA)-induced wounding responses, although none of these were sufficient to confer resistance to the grain aphid. These findings confirm previous studies where rice brown planthopper (Nilaparvata lugens) caused changes in the expression of rice proteins involved in signalling pathways, oxidative stress/apoptosis, wound response, drought response and pathogen-related response (Zhang et al. 2004).

Whilst none of the commercial wheat varieties grown in Europe are resistant to S. avenae or other cereal aphids of European origin (Di Pietro et al. 1998; Migui 2002; Migui and Lamb 2003), some commercial wheat has partial resistance towards Russian wheat aphids, Diuraphis noxia (Mordvilko) (RWA). Ten RWA resistance genes have been identified in T. aestivum and named Dn genes (Ma et al. 1998). Microarray and real-time PCR analysis revealed that more than 180 genes up-regulated on attack by D. noxia are related to reactive oxygen species, signalling, pathogen defence and arthropod allelochemical and physical defence (Smith et al. 2010). In a further study, superoxide dismutase, glutathione reductase and ascorbate peroxidase were uniquely up-regulated in the RWA resistant wheat (T. aestivum) cultivar Tugela DN, compared to the RWA susceptible cultivar Tugela after D. noxia infestation. These findings suggest the involvement of antioxidative enzymes in the RWA–wheat resistance response to minimise toxic effects to plant cells (Moloi and van der Westhuizen 2006, 2008).

Modern wheat varieties are hexaploid and have low genetic diversity for insect resistance traits (Ogbonnaya et al. 2013; Donini et al. 2000). A screen of 87 ancient diploid wheat genotypes, including 67 Triticum monococcum L. genotypes, 13 Triticum boeoticum Bois genotypes, 7 Triticum urartu Tumanian ex Gandilyan genotypes, showed that many exhibited higher resistance to S. avenae than a cultivar of the modern wheat T. aestivum (variety ‘Arminda’; Di Pietro et al. 1998). Accessions of the diploid ancestral wheat—Einkorn wheat, T. monococcum with partial resistance to aphids—have been reported (Migui and Lamb 2004). Furthermore, accessions of wild wheat species, T. boeoticum (Bois), T. tauschii (Coss.) Schmal. and T. araraticum Jakubz., were also found to exhibit high levels of resistance to aphids (Migui and Lamb 2003). Thus, ancient diploid wheat may be a useful source of genes for improving resistance to S. avenae in modern wheat (Di Pietro et al. 1998). However, no previous studies have been carried out to investigate differential gene expression in these lines in response to aphid infestation. The aim of this study was therefore to identify putative defence genes in diploid wheat lines (T. monococcum) in response to grain aphid (S. avenae) feeding using differential proteomics to better understand the basis of this observed resistance/tolerance.

Materials and methods

Plant materials and treatment

Two diploid accessions of wild Einkorn wheat, ACC5 PGR1735 and ACC20 PGR1755, were selected for study, representing lines exhibiting aphid susceptibility and tolerance, respectively. These seeds were kindly donated by R. J. Lamb from seed collections of Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada. They are described as ‘accessions’ in Migui and Lamb (2004). Wheat seedlings were grown to the four-leaf stage in soil (John Innes, No. 2) under controlled environmental conditions in custom-built growth rooms (HA Davie Ltd, U.K.) under the following conditions (light intensity; photosynthetically active photon flux: 600 mol/m2/s, 16:8 LL:DD light regime) with a temperature regime of 18 °C (day):16 °C (night) and 70 % relative humidity.

Aphid bioassays

Grain aphids, S. avenae, were obtained from a laboratory culture and maintained at 20 °C, 55 % relative humidity (R.H.) under a 16:8 LL:DD light regime. The aphids were reared on oats (Avena sativa L., cv. Coast Black), and infested plants were kept in 45 × 45 × 50 cm Perspex cages with new plant material supplied weekly.

Growth, survival and fecundity of S. avenae were evaluated on thirteen accessions of Triticum monoccoccum diploid wheat (Fig. 1). Experiments were also set up using a hexaploid wheat cultivar (Claire) and oats (Coast Black as comparisons). Single seedlings, at the two-leaf stage, of each wheat cultivar and oats were planted in 9-cm pots containing John Innes No. 3 compost and allowed to establish for 2–3 days. To assess fecundity and longevity, two-leaf stage seedlings of the different wheat varieties were each infested with one neonate nymph and randomly arranged within a growth room 20 °C, 55 % R.H. under a 16:8 LL:DD light regime. On each day following infestation, the survival of aphids was monitored, and following ecdysis to the adult stage, the production of nymphs was recorded. Ten replicates were set up for each plant type. To determine mean relative growth rates (MRGRs), neonate nymphs were removed from culture using a fine camel hair paintbrush and weighed on a Mettler AT20 balance. The aphids were then transferred singly to a seedling of one of the wheat varieties or oats. Following infestation, the plants were enclosed in 25 × 9 cm ventilated plastic cylinders to prevent aphid escape and arranged randomly within a growth room maintained at the conditions detailed above. The nymphs were reweighed after 4 days and again when they had moulted to the adult. The mean relative growth rates of aphids developing on the different plants, and over different time scales, were calculated using the methods described by Leather and Dixon (1984).

Thirteen accessions of diploid Einkorn wheat lines together with an oat line (cv. Coast Black) and a hexaploid wheat reference line (cv. Claire) were screened for aphid (Sitobion avenae) resistance using three parameters: mean fecundity (a), longevity (b) and relative growth rates (c). Based on this bioassay data, a resistant (R, ACC20 PGR1755) and a susceptible line (S, ACC5 PGR1735) were selected for further study to investigate potential genes involved in aphid tolerance/resistance using a reverse genetic approach

Data were analysed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). Means were subsequently separated by Tukey–Kramer I tests. Analysis was conducted using GraphPad Prism 5.0.

Aphid infestation for proteomic experiments

The set-up and protocol for aphid infestation on both resistant and susceptible wheat plants (local and systemic treatments) were the same as the ones used by Ferry et al. (2011). In brief, wheat seedlings (four-leaf stage) were infested with S. avenae adults (20 aphids per leaf) confined to two leaves with clip cages (12 plants per treatment). There were 8 treatments in total in this study, as illustrated in the table:

Time of infestation | Time of infestation | |

|---|---|---|

Wheat line | 24 h | 8 days |

Resistant accession | Local | Local |

Systemic | Systemic | |

Susceptible accession | Local | Local |

Systemic | Systemic |

Aphids were left on the seedlings for either 24 h or 8 days after which time they were removed and leaf tissues immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen. Tissues exposed to aphids were designated ‘local treatment’ and the leaves not infested on the same plant designated ‘systemic treatment’. Corresponding tissues were taken from aphid-free control plants for all time points and treatments.

Protein extraction

Leaf samples from 12 experimental plants (4-leaf stage, divided into local and systemic infested tissues) and six control plants were ground to a fine powder using a mortar and a pestle with liquid nitrogen. Samples were pooled into three biological replicates per treatment; six technical replicates of the pooled samples were used in this work. Protein extraction, resuspension, quantification, IEF, SDS-PAGE and staining were carried out following the protocol used in Ferry et al. (2011). In brief, samples were incubated in 10 % (w/v) trichloroacetic acid/acetone with 0.07 % v/v 2-mercaptoethanol at -20 °C for 5 h and then centrifuged at 35,000×g for 20 min. The pellets were washed with ice-cold acetone (0.07 % 2-mercaptoethanol) incubated at −20 °C for 1 h and centrifuged at 12,000×g for 15 min. This wash was repeated six times. Pellets were vacuum dried, and the resultant powder suspended in 7 M urea, 2 M thiourea, 4 % CHAPS, 60 mM DTT, 0.5 % v/v pH 3–10 carrier ampholytes and 1 % v/v protease inhibitor mix (GE Healthcare, Bucks, UK) by sonication. Centrifugation at 20,000×g for 20 min at 4 °C removed insoluble debris, and the total protein content of the supernatant was determined using the 2-D Quant kit (GE Healthcare) method with BSA as standard. Isoelectric focussing (IEF) and SDS-PAGE were carried out essentially according to the manufacturers’ instructions on an Ettan IPGphor II and Ettan DALTsix system (GE Healthcare). For IEF, 18-cm IPG strips with a nonlinear gradient (pH 3–10) were actively rehydrated using 340 μl of DeStreak Rehydration solution (GE Healthcare) at 30 V for 10 h. Five hundred micrograms of protein from each pooled sample was loaded, and IEF conducted at 20 °C under the following conditions: 500 V for 500 Vh, followed by two gradients of 1,000 V for 800 Vh, 8,000 V for 13,500 Vh and finally 8,000 V for 20,000 Vh. The focussed strips were equilibrated for 15 min in 10 mL equilibration solution (75 mM Tris–HCl, 6 M urea, 30 % w/v glycerol, 2 % w/v SDS, 1 % w/v DTT) followed by equilibration in buffer containing 3 % w/v iodoacetic acid for another 15 min. Strips were transferred to a vertical SDS-PAGE gel, and the second dimension performed on a 12.5 % gel using the Ettan DALTsix system (GE Healthcare) at 4 °C. Protein spots were stained with colloidal Coomassie blue G-250 (Sigma).

Image and data analysis

Wet stained gels were scanned using a LabScan 5.0 (GE Healthcare) at a resolution of 600 dpi, bit depth 12. Image analysis, spot detection and quantification were carried out using the Progenesis SameSpots software package version 4.0 and 4.1 (Nonlinear Dynamics, Newcastle, UK). Image and data analysis were as previously described (Ferry et al. 2011). Total spot volume (from matched gel replicates) for each treatment was compared to control images, and a threshold level of ±2-fold change set and subjected to statistical analysis using ANOVA. Spots were determined to be significantly up- or down-regulated when p value was <0.05 (Tukey–Kramer post hoc test). Within group comparisons allowed quality control of images. The molecular masses of protein spots were determined by co-electrophoresis of Mark 12 standard protein markers (Invitrogen), and pI values estimated from the Immobiline DryStrip as per manufacturers recommendations and further calibrated by comparison to published wheat leaf proteomes (Ferry et al. 2011).

MALDI-TOF MS, MS/MS and database search

Selected protein spots from 2D gels with two changes in spot volume after aphid infestation were excised from gel, digested with sequencing grade trypsin (Promega, USA) and subjected to MALDI-TOF MS and MS/MS combined with database searching to assign putative identities to the proteins, as previously described (Ferry et al. 2011). Tryptic peptides were deposited onto 384-well stainless steel target plates manually with a calibration mix (Peptide calibration standard; Bruker Daltonics, Germany) spotted between every 4 sample wells and overlaid with 0.5 μl matrix (CHCA). Peptide mass spectra were recorded using a Bruker UltraFlex II MALDI mass spectrometer in positive reflectron mode over a m/z range of 700–4,500 and analysed using the instruments Flex Analysis software (v3.0). Monoisotopic peak selection was restricted to 50 peptides, and known trypsin autolysis peaks deleted, the peak list was searched against the nrNCBI and Swiss-Prot databases restricted to ‘Viridiplantae’ using the MASCOT (www.matrixscience.com) search engine or a local custom-built restricted database constructed from freely available EST libraries (8,530 wheat and 7,341 barley, http://trifldb.psc.riken.jp/index.pl) with the MASCOT 2.2 software allowing an m/z error of 50 ppm, maximum two missed cleavages, and possible modification of cysteines by carbamidomethylation as well as oxidation of methionine. Protein identification was accepted based on a significant MOWSE score and at least four matched peptide masses. Matching ESTs were queried to the nrNCBI database with a significance cut-off value of 1e-5 using BLASTX searches. Gene ontology (GO) phrases were collected using the PRO protein ontology search engine (http://pir.georgetown.edu/pro/) using the generic GO Slim. Putative protein ID and gene annotation are listed in Tables 1 and 2.

Results

Resistance of diploid wheat lines to grain aphid

A significant impact on the reproductive capacity of S. avenae was recorded when developing on different lines of T. monoccoccum, oats or hexaploid wheat (F 14,111 = 4.67, P < 0.0001) (Fig. 1a). Whilst two diploid lines allowed aphids to produce in excess of 20 offspring per female, five lines only allowed for mean fecundities of less than 5 nymphs per female (Fig. 1a). By comparison, the hexaploid cultivar Claire was intermediate, with aphids producing an average of ca. 13 nymphs per female. Longevity closely reflected fecundity and was also significantly affected by variety (F 14,112 = 3.78, P < 0.0001), such that aphids that produced the largest numbers of offspring typically exhibited the longest lifespans (Fig. 1b). Mean relative growth rate was similarly significantly affected by variety (Fig. 1c), although less markedly than fecundity or longevity (F 14,113 = 8.32, P < 0.0001). Notably, the growth rate was highest on the commercial hexaploid wheat variety (Claire) and the habitual laboratory host, oats (Coast Black). These bioassays thus identified the following as exhibiting resistance to S. avenae: ACC16 INRA TM44, ACC17 PGR1752, ACC20 PGR1755, ACC26 PGR1761 and ACC27PGR1762, whilst ACC5 PGR1735 and ACC PGR1758 showed susceptibility to S. avenae. Based on these bioassays, the resistant diploid line (ACC20 PGR1755; #11) and the susceptible line ACC5 PGR1735 were selected in the present study to investigate genes and proteins potentially involved in the observed aphid resistance/tolerance.

Proteome responses of wheat seedlings to aphid infestation

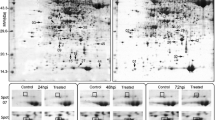

Local and systemic changes in the wheat leaf proteome in both a resistant diploid line (ACC20 PGR1755) and a susceptible diploid line (ACC5 PGR1735) in response to aphid infestation were investigated. Two time points were selected, 24 h (early response) and 8 days (late response). The proteome maps for 24 h and 8 days post-treatment control gels were consistent with previous 2-D gel separations reported for wheat and barley leaves (Geddes et al. 2008; Jiang et al. 2008; Ferry et al. 2011).

Proteome maps of wheat leaf tissues from each treatment (a resistant and a susceptible line) were compared with their respective controls using Progenesis SameSpots software (S Fig 1) and differentially regulated proteins identified by MS and MS/MS searches of nrNCBI/Swiss-Prot and a locally restricted wheat EST database. Differentially expressed proteins identified after 24 h and 8 days aphid infestation are presented in Tables 1 and 2, respectively. For both time points, both local and systemic responses were investigated. Approximately 200 protein spots were detected on each gel, with the differences in protein expression levels between a given line/time point/feeding site with its respective control varying from 4 to 34 protein spots. In the susceptible line, 16 protein spots were significantly up-regulated after 24-h aphid feeding, with 12 being involved in the local response and 4 involved in the systemic response, but after 8 days the up-regulated spots had decreased to 12 (8 locally and 4 systemically). In contrast, in the resistant line, 28 protein spots were significantly up-regulated after 24-h aphid feeding (17 locally and 11 systemically), and the number of up-regulated spots increased to 41 (37 locally and 4 systemically) after 8 days. Thus, the data show that more proteins were observed to be up-regulated in the resistant line at day 8 compared to the other treatments.

Differentially expressed proteins in response to aphid infestation over time

Identified up-regulated protein spots listed in Tables 1 and 2 are grouped by functional categories in Fig. 2a, b. The results clearly show that the majority of identified proteins that were differentially regulated in both the resistant (ACC20 PGR1755) and susceptible (ACC5 PGR1735) diploid line following aphid infestation were involved in photosynthesis or other metabolic processes or were classified as being uncharacterised/unknown. Other proteins identified in both lines were shown to be involved in: ATP synthesis, proteolysis, post-translational modification, immune response, nuclear mRNA splicing, mRNA and miRNA processing, chromosome organisation, cell division and cytokinesis (Tables 1, 2). However, there were notable differences in the response of these two lines, particularly in respect of the up-regulation of general and specific stress response proteins. Importantly, these results show that proteins known to be involved in the stress response and the defence response were clearly induced in the resistant line, but not the susceptible line, in response to aphid infestation (Fig. 3a, b) and that different proteins were up-regulated at different time points. Thus, both spatial and temporal effects were observed. For example, at 24 h (representing an early response), a heat stress TF and dehydrin were up-regulated as part of the local response, whereas NBS–LRR type resistant protein was up-regulated as part of the systemic response. At 8 days (late response), a different set of proteins (two putative stress-induced protein sti1, putative viral resistance protein, MEDsa GLB1 and HSP20-like chaperone) was up-regulated as part of the local response, whilst a NBS-containing resistance-like protein was up-regulated as part of the systemic response. Additionally, at 24 h post-infestation, transcription factors and proteins with roles in signalling were shown to be clearly induced in the resistant line; by day 8, proteins involved in protein synthesis were shown to be up-regulated in this line. Interestingly, DNA repair proteins were also up-regulated in the resistant line. These results also show that the majority of the up-regulated proteins (in terms of number) were induced locally rather than systemically (Fig. 2a, b).

Changes in diploid wheat leaf proteins following aphid infestation for 24 h (a) or for 8 days (b). Proteins identified were assigned to categories based on biological process GO terms, shown as number of total response in each category for each treatment. Proteins that could not be identified were not included. First character: R resistant line, S susceptible line. Second character: L local tissues, S systemic tissues

Global changes in wheat leaf proteins following aphid infestation of (a) the susceptible diploid line (ACC5 PGR#1735) and b the resistant diploid line (ACC20 PGR1755). Proteins identified were assigned to categories based on biological process GO terms, shown as number of total response in each category for each line at all time points tested. The results show that proteins involved in the stress response and the defence response were up-regulated in the resistant line, but only in response to aphid feeding. No such proteins were identified in the susceptible line either prior to, or following aphid infestation. (Color figure online)

General stress response proteins

The fold change (in normalised spot volume) for selected stress response proteins up-regulated in the resistant line in response to aphid infestation is presented in Table 3. The heat stress transcription factor A-5 (Oryza sativa) and dehydrin (Nicotiana tabacum) were up-regulated 2.6- and 2.9-fold, respectively, in the resistant line after 24-h aphid infestation (local response), as was a lipoxygenase (Oryza sativa), a compound with multiple roles including plant response to stress, where the normalised spot volume showed a 3.2-fold increase. A putative stress-induced protein Sti1 (Oryza sativa and Arabidopsis thaliana), a non-symbiotic haemoglobin 1 MEDsa GLB1 (Medicago sativa) and a protein with similarity to guanylate binding proteins from Arabidopsis were also up-regulated in this line (3.5-, 3.7-, 2.8- and 2.2-fold increases, respectively), but only after 8 days aphid infestation (local response). In addition to these general stress response proteins, proteins with known roles in plant defence and apoptosis, such as NBS–LRR type resistance protein (Oryza sativa), were also shown to be systemically up-regulated in the resistant line after 24-h aphid infestation (2.4-fold increase). After 8 days of aphid feeding, a putative viral resistance protein (Oryza sativa) was identified as part of the local response in this resistant line (4.3-fold increase), whilst an NBS-containing resistance-like protein was identified as part of the systemic response (2.7-fold increase). Interestingly, proteins involved in protein synthesis and transcriptional regulation (ras-related protein Rab-18, Zea mays, 2.1-fold increase) were also up-regulated in the resistant line, but none were identified as being up-regulated in the susceptible line in response to aphid infestation (Fig. 2a, b; Table 3). Other proteins such as chaperones (SGS; HSP20-like chaperone, Medicago truncatula, 4.1-fold increase) and heat-shock proteins (sti 1) were also shown to be induced in the resistant line after 8 days post-aphid infestation. No stress/defence proteins were identified in the susceptible line in response to aphid infestation.

Oxidative stress response proteins

Of particular interest, proteins associated with oxidative stress caused by insect herbivores were detected. After 24-h aphid infestation (local response), one stress response protein, called dehydrin from cultivated tobacco, and one redox protein from Arabidopsis (Table 1, spot RL v RC 1), were identified putatively in resistant plants, whilst after 8 days, a further three stress response proteins, putative stress-induced protein sti1 (from rice), non-symbiotic haemoglobin 1 (from alfalfa) and a stress-induced protein sti1-like protein (from Arabidopsis), which is involved in response to hydrogen peroxide and oxidative stress, were identified in these resistant plants. Surprisingly, no such protein was identified in the resistant plants as a systemic response, and neither were any such proteins identified in the susceptible plant line, irrespective of the time frame (24 h or 8 days).

Proteins involved in photosynthesis and metabolism

Proteins involved in photosynthesis and metabolism formed the majority of proteins differentially expressed in either the susceptible or the resistant line in response to aphid infestation; interestingly, more proteins in these categories were detected after 24-h than 8-day aphid infestation (Tables 1, 2). Putative proteins involved in photosynthesis that were shown to be up-regulated locally in the resistant line at 24 h post-infestation included the large subunit of ribulose-1, 5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase and two ribulose bisphosphate oxygenase carboxylase activase from barley. Putative proteins involved in metabolism that were up-regulated locally at this same time point included a lipase class 3 family protein from rice (lipid metabolism), whilst a methyltransferase (Os06g0128100 protein from rice) was identified locally in these resistant plants, but after 8 days. Proteins with roles in protein degradation were also noted to be differentially regulated. For example, a protein with cysteine-type peptidase activity (OSJNBb0003B01.14 protein from rice) was identified putatively in the resistant line after 8 days aphid infestation as part of the local response, whilst a cell division protease (ftsH homolog 2 from rice), which is a probable ATP-dependent zinc metallopeptidase with hydrolase, metalloprotease and protease activities, was identified putatively as part of the local response in susceptible plants after 24-h aphid infestation.

Proteins involved in transcriptional regulation

Proteins with roles in transcriptional regulation were also changed in response to aphid infestation, but predominantly in the susceptible wheat genotype. For example, a protein called At1g55310 from Arabidopsis, which is involved in nuclear mRNA splicing, was identified putatively in the susceptible line at 24 h post-local aphid infestation, whilst 5′-3′ exoribonuclease 2 (from Arabidopsis), which is involved in mRNA processing and miRNA catabolic processes, was also identified putatively in these plants after 24 h, but only as part of the systemic response. Furthermore, a putative uncharacterised protein, OSJNBa0042F15.18 from rice, which is involved in DNA integration and RNA-dependent DNA replication, was identified putatively in the susceptible line after 24-h aphid local infestation. After 8d aphid infestation (local), two retrotransposon proteins, known to be involved in RNA-dependent DNA replication, were identified putatively in the resistant genotype after 24-h aphid infestation as part of the local response.

Discussion

The preliminary bioassays carried out with diploid wheat lines and a standard commercial cultivar showed clear differences in susceptibility towards cereal aphids, although none of the lines tested showed strong resistance in the sense of causing significant levels of mortality of the pest. However, the partial resistance observed is sufficient to be useful in minimising cereal aphid outbreaks in the field by slowing the rate of population increase and thus provide a useful basis for further investigation. These results allowed two diploid wheat lines to be selected for a ‘resistant’ versus ‘susceptible’ comparison by proteomic analyses. The proteomics results showed that there were notable differences in terms of proteins up-regulated between the resistant and susceptible diploid wheat lines in response to aphid feeding. In this study, only up-regulated proteins were identified, as they are more likely to be directly involved in plant resistance to aphid infestation. Down-regulated proteins are likely to be the result of aphid manipulation or sabotage of plant defence (Smith and Boyko 2007).

Previous studies demonstrated that two-dimensional gel protein electrophoresis followed MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry (MS and MS/MS) was an effective initial tool for identifying differentially expressed proteins in wheat in response to aphid infestation (Ferry et al. 2011). Although the wheat genome has not been fully annotated, over 50 % of the protein spots excised from gels could be putatively identified as showing significant similarity to known wheat or other cereal/plant genes using NCBI, Swiss-Prot and wheat EST databases. Results from the previous study using the commercial line Claire (T. aestivum, hexaploid, AuAuBBDD) showed little resistance to aphid feeding, and thus, the diploid accessions were investigated as potential sources of aphid resistance genes/gene products (Diploid AmAm; T. monococcum) for exploitation in subsequent breeding programmes.

The present study could not definitively identify any specific gene-for-gene interactions between the diploid wheat T. monococcum and the grain aphid S. avenae, although proteins with similarity to NBS–LRR (nucleotide-binding site leucine-rich repeat) resistance proteins were identified as being systemically induced in the resistant line (ACC20 PGR1755) (Table 3). Most of the disease resistance genes (R genes) in plants cloned to date encode nucleotide-binding site leucine-rich repeat (NBS–LRR) proteins characterised by nucleotide-binding site (NBS) and leucine-rich repeat (LRR) domains. These abundant proteins are involved in the detection of pathogens (bacteria, viruses, fungi), nematodes and insects (McHale et al. 2006). Plant NBS–LRR proteins are numerous and are encoded by one of the largest gene families known in plants (Monosi et al. 2004). Disease resistance is the only function so far demonstrated for NBS–LRR proteins; however, a role in resistance has yet to be confirmed for most (Deslandes et al. 2002). Little is known about the regulation of the plant genes that encode NBS–LRRs. Consistent with the need for a rapid response to pathogen attack, many NBS–LRR-encoding genes are constitutively expressed at low levels in healthy, unchallenged tissue, although some show tissue-specific expression (McHale et al. 2006). They are upregulated, however, in response to bacterial flagellin, which induces basal resistance, suggesting that plants can establish a state of heightened sensitivity to pathogen attack (Zipfel et al. 2004). The tomato Mi-1 gene encoding an NBS–LRR-like protein confers resistance to both root-knot nematodes and potato aphids (Vos et al. 1998; Li et al. 2006), and aphid resistance in Medicago truncatula involves antixenosis and phloem-specific, inducible antibiosis, which maps to a single locus flanked by NBS–LRR resistance gene analogues (Klingler et al. 2005). Thus, findings from the present study provide the basis for a future molecular analysis of aphid resistance.

The diploid resistant line also responded to aphid infestation by significant up-regulation of stress response proteins, oxidative stress response proteins, defensive proteins and transcriptional regulators; interestingly, these same proteins were not detected in the susceptible line ACC5 PGR1735 in response to aphid infestation (Fig. 2a, b). This result suggests that the above proteins are playing a role in the observed resistance/tolerance of line ACC20 PGR1755 to aphid infestation. Furthermore, the diploid resistant wheat exhibited greater up-regulation of DNA synthesis/replication/repair proteins, which could have potential impact on plant resistance/tolerance to aphids and plant survival under aphid attack and oxidative stress.

Overall, the aphid responsive changes in the diploid wheat lines investigated were both spatially and temporally regulated, with differences between the two time points (24 h and 8 days), as well as differences in local and systemic responses (Tables 1, 2, 3; Fig. 2a, b). These proteins are grouped by functional categories (Fig. 3) to allow comparison between the resistant and susceptible lines and their potential roles discussed below.

Metabolism related proteins

Plants experience a metabolic re-programming when attacked by herbivores; genes that are involved in photosynthesis may be up-regulated to compensate for nutritional loss caused by aphid attack (Smith and Boyko 2007). Photosynthetic adjustments in wheat can significantly contribute to its tolerance to damage/metabolic drain caused by Russian wheat aphid (RWA; D. noxia; Haile et al. 1999). In the present study, several enzymes involved in photosynthesis and ATP synthesis were up-regulated in response to aphid infestation (ribulose-1, 5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase large subunit, ribulose bisphosphate oxygenase carboxylase activase and ATPase alpha subunit) after 24-h infestation. Similar changes in metabolic processes were detected in both rice and barley following insect or pathogen attack, respectively (Wei et al. 2009; Geddes et al. 2008). Differential expression of photosynthetic or photorespiration genes have also been observed for Myzus persicae feeding on leaves of celery, D. noxia feeding on wheat foliage, M. nicotianae feeding on Nicotiana attenuata foliage, Schizaphis graminum feeding on N. attenuata foliage (Smith and Boyko 2007) and Bemisia tabaci feeding on Arabidopsis (Yin et al. 2012). These changes indicate the potential switch of plant metabolic resources from normal growth to defensive functions, when it is subjected to attack by phloem feeders. Thus, we also observe changes in protein turnover as plants adapt to different environmental conditions, including the challenge raised by insect pests (Pickart and Eddins 2004; Dreher and Callis 2007).

In the present study, a protein, OSJNBb0003B01.14 (Table 2, spot 20), with proteolysis/cysteine-type peptidase activity was found to be up-regulated locally after 8 days aphid infestation in the resistant line. Feng et al. (2003) showed similar results of regulated proteolysis of endogenous proteins can be a contributing factor to plant defence against insect pests. Similarly, changes in transcriptional regulators are essential to plants under different abiotic and biotic stresses. In this study, heat stress transcription factor A-5 (Table 1, spot RLvsRC2) and a Dof zinc finger protein (Fragment) (Table 1, spot RLvsRC8) were up-regulated locally in the resistant line 24-h post-aphid infestation. These findings are in agreement with those of other studies that suggest that transcription factors play an important role in plant response to environmental changes through regulation of plant signalling pathways (Lucyshyn and Wigge 2009; Koini et al. 2009; Casson et al. 2009). Metabolic reprogramming is further illustrated by results showing that aphid feeding up-regulates proteins involved in mRNA and miRNA processing (Fig. 2a, b), which in turn leads to changes in protein synthesis. Similar results have been shown for RWA feeding on wheat leading to the up-regulation of transcripts that are involved in protein synthesis (Boyko et al. 2006; Smith et al. 2010).

Stress response and oxidative stress response proteins

Components of aphid salivary secretions are known to generate local and systemic production of reactive oxygen species (ROS; Tjallingii 2006), which is a commonly known early plant response to biotic stress (Apel and Hirt 2004; Bolwell and Wojtaszek 1997). ROS are important for plant signalling under insect attack, but can cause oxidative damage of membrane integrity due to lipid peroxidation, and can also generate highly cytotoxic compounds in the process. Therefore, plants have to enhance their resistance mechanisms, such as ROS scavenging and cell defence, to maintain homeostasis under stress conditions.

In this study, stress response proteins were identified as up-regulated in the resistant line after both 24-h and 8-day aphid infestation. A heat stress transcription factor A-5 (Oryza sativa, 24 h RL) and dehydrin (Nicotiana tabacum, 24 h RL) were induced early in the response, whilst after 8 days other known stress response proteins were induced including non-symbiotic haemoglobin 1, MEDsa GLB1 (Medicago sativa, 8 days RL) and two putative stress-induced protein sti1 (O. sativa and Arabidopsis, 8 days RL). The stress-induced protein sti1-like proteins (Table 3, induced in the resistant line as part of the local response, 8 days after infestation) are also thought to be induced in response to hydrogen peroxide and oxidative stress (Sano et al. 2013). Additionally, a hypothetical protein (Arabidopsis, 24 h RL, spot 1) is also thought to have a role in oxidative stress. These results indicate that diploid wheat plants recognised aphid infestation as a threat and a general stress response was triggered at or near the site of feeding, which was shown by the up-regulation of multiple stress-related proteins in leaves of the resistant line (24 h RL or 8 days RL). Interestingly, this stress response was not detected in the susceptible wheat line under the same treatment or the systemically infested resistant wheat leaves. This conclusion is further supported by the identification of induction of heat-shock proteins (HSPs) in the resistant line in response to aphid infestation. Stresses usually cause protein dysfunction, and maintaining functional proteins is particularly important for cell survival under stress. Many HSPs act as chaperones during protein folding, assembly, translocation and degradation, and can assist in protein refolding under stress conditions: for example, the HSP-70 chaperone system is crucial during both the stress response and development because protein misfolding and aggregation disrupt cellular homeostasis (Koizumi et al. 2014). They thus protect plants against stress by re-establishing normal protein conformation and hence cellular homeostasis (Wang et al. 2004). Similar results have been reported in other systems, for example, several proteins with putative functions in stress responses were identified in barley in response to Rhopalosiphum padi infestation (Gaupels et al. 2008). However, some chaperones are also multifunctional and may show enzymatic functions besides roles in protein folding (Scranton et al. 2012).

The induction of oxidative stress following aphid feeding is suggested by the identification of two stress-induced protein sti1-like proteins (Table 3) in this study and indeed in other aphid studies. Previous studies have shown that D. noxia infestation significantly induced an early accumulation of hydrogen peroxide and not only increased NADPH oxidase activity in a resistant (cv. Tugela DN) wheat line (Moloi and van der Westhuizen 2006), but also antioxidative enzyme activity in this same resistant wheat line compared to a susceptible wheat line (Moloi and van der Westhuizen 2008). Thus, the ability to control ROS levels in the wheat plant is closely linked to its resistance to aphid infestation. Oxidative stress is one of the first general reactions to the damage caused by phloem-feeding insects when they penetrate the plant (Wei et al. 2009). The expression of oxidative stress-related proteins, including a catalase, an ascorbate peroxidase and five extracellular class III peroxidases, was significantly increased in rice (O. sativa) in response to the brown plant hopper (Nilaparvata lugens; Wei et al. 2009). Proteomic studies carried out by Collins et al. (2010) revealed that proteins known to be involved in limiting ROS were more abundant in the resistant rather than susceptible varieties of Arabidopsis when under insect stress. Oxidative stress may also explain why proteins involved in DNA repair were identified in the present study. Interestingly, there are more DNA processing proteins up-regulated in the resistant line than the susceptible line following aphid feeding, suggesting some involvement of these proteins in the observed resistance/tolerance of line ACC20 PGR1755 to aphid infestation. Micro-array studies have similarly identified transcripts involved in DNA repair in Arabidopsis following aphid infestation, for example the increased expression of a nucleoside diphosphate-linked moiety transcript (Couldridge et al. 2007). Filkowski et al. (2004) found that mutant Arabidopsis lines impaired in certain aspects of protection against elevated levels of free radicals induce the production of scavenging enzymes earlier than wild-type plants. The higher levels of radical species resulted in the increased incidence of spontaneous double-strand breaks resulting in a higher expression of DNA repair genes. Gene sequences putatively involved in DNA synthesis were identified in wheat plants containing Dn genes in response to RWA biotype I attack (Boyko et al. 2006).

In addition to investigating both local and systemic responses in diploid wheat lines to aphid infestation, the present study also investigated this response over time to represent both an early response (24 h) and late response (8 days). Whilst stress and defence proteins were up-regulated at both time points, these represented different stress proteins, with more occurring during the late response phase. Interestingly, transcription factors and proteins with roles in signalling were shown to be induced during the early phase, as opposed to the late phase. Few studies have attempted to investigate these responses either over time or at the proteome level. Previous studies have shown that changes in transcript expression in wheat in response to RWA, where tolerance has previously been well characterised, comprise two phases: an immediate response (i.e. hypersensitive response) 24 h after infestation with RWA and a second prolonged response that prevails in the tissue for an extended period of time (i.e. systemic acquired resistance) (Botha et al. 2006), although differences in expression of transcripts were not reported. However, recently this same group has reported the differential regulation of transcripts involved in stress, signal transduction, photosynthesis, metabolism and gene regulation in susceptible wheat lines in response to RWA to better understand the different modes of resistance in wheat to this aphid species and the role of Dn genes (Botha et al. 2014). The ability of these genes to confer tolerance to S. avenae is currently being investigated.

Ultimately, the aim of the present study was to try to identify potential aphid resistance proteins. An NBS–LRR type resistance protein, types of which are known to be involved in apoptosis and plant defence (Takken and Joosten 2000; De Young and Innes 2006), was found to be up-regulated systemically in the resistant line following 24-h aphid infestation (Table 3). Furthermore, a putative viral resistance protein was shown to be up-regulated locally in the resistant line post 8 days aphid infestation as was the NBS-containing resistance-like protein (Table 3); however, in this case, the protein was systemically up-regulated. Both proteins have previously been shown to be involved in apoptosis and plant defence responses (Takken and Joosten 2000; De Young and Innes 2006; Rossignol et al. 2006). Possible involvement of these proteins in aphid resistance may occur, although further study is required to confirm and better understand their contributions to the observed resistance.

Currently, there is a major focus to identify potential aphid resistance genes through the study of aphid-induced gene expression (Thompson and Goggin 2006; De Vos et al. 2007; Smith et al. 2010). However, previous studies with commercial wheat lines have shown that this crop has a relatively poor inducible defence system (Ferry et al. 2011). Whilst there was very little evidence of any local induction of defensive proteins, e.g. proteinase inhibitors or other wound-responsive genes in response to grain aphid infestation (Thompson and Goggin 2006; Ferry et al. 2011) in this study, it does give new insights into the aphid-stress response in diploid wheat. The results suggest that stress response, oxidative stress response, defence response, apoptosis and DNA synthesis/replication/repair proteins play an important role in conferring resistance in the diploid line studied to S. avenae. This study indicates that the resistant diploid line ACC20 PGR1755 may provide a valuable resource in breeding wheat for resistance to aphids.

References

Apel K, Hirt H (2004) Reactive oxygen species: metabolism, oxidative stress, and signal transduction. Annu Rev Plant Biol 55:373–399

Bolwell GP, Wojtaszek P (1997) Mechanisms for the generation of reactive oxygen species in plant defence—a broad perspective. Phys Mol Plant Path 51:347–366

Botha A-M, Lacock L, van Niekerk C, Matsioloko MT et al (2006) Is photosynthetic transcriptional regulation in Triticum aestivum L. cv. ‘TugelaDN’ a contributing factor for tolerance to Diuraphis noxia (Homopera: Aphididae)? Plant Cell Rep 25:41–54

Botha A-M, van Eck L, Burger NFV, Swanevelder ZH (2014) Near-isogenic lines of Triticum aestivum with distinct modes of resistance exhibit dissimilar transcriptional regulation during Diuraphis noxia feeding. Biol Open. doi:10.1242/bio.201410280

Boyko EV, Smith CM, Thara VK, Bruno JM, Deng YP, Starkey SR, Klaahsen DL (2006) Molecular basis of plant gene expression during aphid invasion: wheat Pto- and Pti-like sequences are involved in interactions between wheat and Russian wheat aphid (Homoptera: Aphididae). J Econ Entomol 99:1430–1445

Casson SA, Franklin KA, Gray JE, Grierson CS et al (2009) Phytochrome B and PIF4 regulate stomatal development in response to light quantity. Curr Biol 19:229–234

Collins RM, Afzal M, Ward DA, Prescott MC et al (2010) Differential proteomic analysis of arabidopsis thaliana genotypes exhibiting resistance or susceptibility to the insect herbivore, Plutella xylostella. PLos One (open access publishing)

Couldridge CE, Newbury HJ, Ford-Lloyd BV, Bale JS, Pritchard J (2007) Exploring plant responses to aphid feeding using a full Arabidopsis microarray reveals a small number of genes with significantly altered expression. Bull Entomol Res 97:523–532

De Vos M, Van Oosten VR, van Poecke RMP, Van Pelt JA et al (2005) Signal signature and transcriptome changes of Arabidopsis during pathogen and insect attack. Mol Plant Microbe 18:923–937

De Vos M, Kim J-H, Jander G (2007) Biochemistry and molecular biology of Arabidopsis-aphid interactions. BioEssays 29:871–883

De Young BJ, Innes RW (2006) Plant NBS–LRR proteins in pathogen sensing and host defense. Nat Immunol 7:1243–1249

Deslandes L, Olivier J, Theulieres F, Hirsch J, Feng DX, Bittner-Eddy P, Beynon J, Marco Y (2002) Resistance to Ralstonia solanacearum in Arabidopsis thaliana is conferred by the recessive RRS1-R gene, a member of a novel family of resistance genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 99:2404–2409

Devonshire AL, Field LM (1991) Gene amplification and insecticide resistance. Ann Rev Entomol 36:1–23

Di Pietro JP, Caillaud CM, Chaubet B, Pierre JS, Trottet M (1998) Variation in resistance to the grain aphid, Sitovion avenae (Sternorhynca: Aphididae), among diploid wheat genotypes: multivariate analysis of agronomic data. Plant Breed 117:407–412

Donini P, Law JR, Koebner RMD, Reeves J, Cooke RJ (2000) Temporal trends in the diversity of UK wheat. Theor Appl Genet 100:912–917

Dreher KA, Callis J (2007) Ubiquitin, hormones and biotic stress in plants. Ann Bot 9:787–822

Farmer EE, Ryan CA (1992) Octadecanoid precursors of jasmonic acid activate the synthesis of wound-inducible proteinase inhibitors. Plant Cell 4:129–134

Feng W, Shi Y, Li M, Zhang M (2003) Tandem PDZ repeats in glutamate receptor-interacting proteins have a novel mode of PDZ domain-mediated target binding. Nat Struct Biol 10:972–978

Ferry N, Stavroulakis S, Guan W, Davison GM, Bell HA, Weaver RJ, Down RE, Gatehouse JA, Gatehouse AMR (2011) Molecular interactions between wheat and cereal aphid (Sitobion avenae); analysis of changes to the wheat proteome. Proteomics 11:1985–2002

Filkowski J, Kovalchuk O, Kovalchuk I (2004) Genome stability of vtc1, tt4, and tt5 Arabidopsis thaliana mutants impaired in protection against oxidative stress. Plant J 38:60–69

Gatehouse JA (2002) Plant resistance towards insect herbivores: a dynamic interaction. New Phytol 156:145–169

Gaupels F, Buhtz A, Knauer T, Deshmukh S et al (2008) Adaptation of aphid stylectomy for analyses of proteins and mRNAs in barley phloem sap. J Exp Bot 59(12):3297–3306

Geddes J, Eudes F, Laroche A, Selinger LB (2008) Differential expression of proteins in response to the interaction between the pathogen Fusarium graminearum and its host. Hordeum Vulgare Proteomics 8:545–554

Haile FJ, Higley LG, Ni XZ, Quisenberry SS (1999) Physiological and growth tolerance in wheat to Russian wheat aphid (Hopoptera: Aphididae) injury. Environ Entomol 28(5):787–794

Havlícková H (1993) Level and nature of the resistance to the cereal aphid, Sitobion avenae (F.), in thirteen winter wheat cultivars. J Agron Crop Sci 171:33–137

Jiang Q, Chen H, Pan X, Shi Y et al (2008) Proteomic analysis of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) hybrid necrosis. Plant Sci 175:394–401

Klingler J, Creasy R, Gao L, Nair RM, Calix AS, Jacob HS, Singh KB (2005) Aphid resistance in Medicago truncatula involves antixenosis and phloem-specific, inducible antibiosis, and maps to a single locus flanked by NBS–LRR resistance gene analogs. Plant Physiol 137(4):1445–1455

Koini MA, Alvey L, Allen T, Tilley CA et al (2009) High temperature-mediated adaptations in plant architecture require the phytochrome-interacting bHLH factor PIF4. Curr Biol 19:408–413

Koizumi S, Ohama N, Mizoi J, Shinozaki K, Yamaguchi-Shinozaki K (2014) Functional analysis of the Hikeshi-like protein and its interaction with HSP70 in Arabidopsis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 450:396–400

Leather SR, Dixon AFG (1984) Aphid growth and reproductive rates. Ent Exp Appl 35:137–140

Li Q, Xie QG, Smith-Becker J, Navarre DA et al (2006) Mi-1-mediated aphid resistance involves salicylic acid and mitogen-activated protein kinase signalling cascades. Mol Plant Microbe Interact 19:655–664

Lucyshyn D, Wigge PA (2009) Plant development: PIF4 integrates diverse environmental signals. Curr Biol 19:265–266

Ma Z-Q, Saidi A, Quick JS, Lapitan NLV (1998) Genetic mapping of Russian wheat aphid resistance genes Dn2 and Dn4 in wheat. Genome 41(2):303–306

McHale L, Tan X, Koehl P, Michelmore RW (2006) Plant NBS–LRR proteins: adaptable guards. Genome Biol 7:212

Migui SM (2002) Host relationships of three aphid species on wheat in the genus Triticum: potential for crop resistance in spring wheat. PhD thesis, University of Manitoba, Winnipeg, Canada

Migui SM, Lamb RJ (2003) Patterns of resistance to three cereal aphids among wheats in the genus Triticum (Poaceae). Bull Entomol Res 93(4):323–333

Migui SM, Lamb RJ (2004) Seedling and adult plant resistance to Sitobion avenae (Hemiptera: Aphididae) in Triticum monococcum (Poaceae), an ancestor of wheat. Bull Entomol Res 94:35–46

Moloi MJ, van der Westhuizen AJ (2006) The reactive oxygen species are involved in resistance responses of wheat to the Russian wheat aphid. J Plant Physiol 163(11):1118–1125

Moloi MJ, van der Westhuizen AJ (2008) Antioxidative enzymes and the Russian wheat aphid (Diuraphis noxia) resistance response in wheat (Triticum aestivum). Plant Biol 10(3):403–407

Monosi B, Wisser RJ, Pennill L, Hulbert SH (2004) Full-genome analysis of resistance gene homologues in rice. Theor Appl Genet 109:1434–1447

Moran PJ, Thompson GA (2001) Molecular responses to aphid feeding in Arabidopsis in relation to plant defence pathways. Plant Physiol 125:1074–1085

Moran P, Cheng Y, Cassell JL, Thompson GA (2002) Gene expression profiling of Arabidopsis thaliana in compatible plant-aphid interactions. Arch Insect Biochem Phys 51:182–203

Ogbonnaya FC, Abdalla O, Mujeeb-Kazi A, Kazi AG, Xu SS, Gosman N, Lagudah ES, Bonnett D, Sorrells ME, Tsujimoto H (2013) Synthetic Hexaploids: Harnessing Species of the Primary Gene Pool for Wheat Improvement. In: Janick J (ed) Plant Breeding Reviews, vol 37. Wiley, New York, pp 35–122. doi:10.1002/9781118497869.ch2

Pickart CM, Eddins MJ (2004) Ubiquitin: structures, functions, mechanisms. Biochim Biophys Acta 695:55–72

Rossignol M, Peltier J-B, Mock H-P, Matros A et al (2006) Plant proteome analysis: a 2004–2006 update. Proteomics 6(20):5529–5548

Sano N, Masaki S, Tananari T, Yamada T, Hirasawa T, Kanekatsu M (2013) Proteomic analysis of stress-related proteins in rice seeds during the desiccation phase of grain filling. Plant Biotechnol 30:147–156

Scranton MA, Yee A, Park SY, Walling LL (2012) Plant leucine aminopeptidases moonlight as molecular chaperones to alleviate stress-induced damage. J Biol Chem 22:18408–18417

Smith CM (2005) Plant resistance to arthropods—molecular and conventional approaches. Springer, Berlin

Smith CM, Boyko EV (2007) The molecular bases of plant resistance and defence responses to aphid feeding: current status. Entomol Exp Appl 122:1–16

Smith CM, Liu X, Wang LJ, Liu X, Chen M-S, Starkey S, Bai J (2010) Aphid feeding activates expression of transcriptome of oxylipin-based signals in wheat involved in resistance to herbivory. J Chem Ecol 36:260–276

Takken FLW, Joosten MHAJ (2000) Plant resistance genes: their structure, function and evolution. Eur J Plant Pathol 106:699–713

Thompson GA, Goggin FL (2006) Transcriptomics and functional genomics of plant defence induction by phloem-feeding insects. J Exp Bot 57:755–766

Tjallingii WF (2006) Salivary secretions by aphids interacting with proteins of phloem wound responses. J Exp Bot 57(4):739–745

United Nations (2012) Searchable online statistical database from Food and Agriculture Division of the United Nations. FAOSTAT

Vos P, Simons G, Jesse T, Wijbrandi J, Heinen L, Hogers R, Zabeau M (1998) The tomato Mi-1 gene confers resistance to both root-knot nematodes and potato aphids. Nat Biotechnol 16(13):1365–1369

Walling LL (2000) The myriad plant responses to herbivores. J Plant Growth Regul 19:195–216

Wang W, Vinocur B, Shoseyov O, Altman A (2004) Role of plant heat-shock proteins and molecular chaperones in the abiotic stress response. Trends Plant Sci 9:244–252

Wang C-P, Wang Z-H, Zhao H-Y, Zhu Q-D, Luo K, Wang L-M, Dong P-H (2013) Expression of potential resistance genes to the english grain aphid, Sitobion avenae, in wheat, Triticum aestivum. J Insect Sci 13:90. doi:10.1673/031.013.9001

Wei Z, Hu W, Lin QS, Cheng XY et al (2009) Understanding rice plant resistance to the Brown Planthopper (Nilaparvata lugens): a proteomic approach. Proteomics 9:2798–2808

Yin H, Yan F, Ji J, Li Y, Wang R, Xu C (2012) Proteomic analysis of Arabidopsis thaliana leaves infested by tobacco whitefly Bemisia tabaci (Gennadius) B biotype. Plant Mol Biol Rep 30:379–390

Yuan H, Chen X, Zhu L, He G (2005) Identification of genes responsive to brown planthopper Nilaparvata lugens Stål (Homoptera: Delphacidae) feeding in rice. Planta 221:105–112

Zhang F, Zhu L, He G (2004) Differential gene expression in response to brown planthopper feeding in rice. J Plant Physiol 161:53–62

Zipfel C, Robatzek S, Navarro L, Oakeley EJ, Jones JD, Felix G, Boller T (2004) Bacterial disease resistance in Arabidopsis through flagellin perception. Nature 428:764–767

Acknowledgments

Funding to support the work described in this paper was provided by the BBSRC (Crop Science Initiative; Grant BB/E006280/1) and is gratefully acknowledged. The authors would like to thank R. J. Lamb for the diploid wheat seeds that were kindly donated from the seed collections of Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada and for critically commenting on the MS. The authors also thank the British Wheat Breeders for advice and support throughout the programme.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Wenzhu Guan and Natalie Ferry have equally contributed to this work.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

11032_2015_220_MOESM1_ESM.ppt

Supplementary material 1 Leaf proteome of resistant wheat (R, ACC20 PGR1755) following 24-h aphid infestation showing the local response versus non-infested leaf proteome of same aged resistant wheat plants. Up-regulated protein spots of twofold change or greater are indicated by O; down-regulated protein spots of twofold change or greater are indicated by O (PPT 3092 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License which permits any use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and the source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Guan, W., Ferry, N., Edwards, M.G. et al. Proteomic analysis shows that stress response proteins are significantly up-regulated in resistant diploid wheat (Triticum monococcum) in response to attack by the grain aphid (Sitobion avenae). Mol Breeding 35, 57 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11032-015-0220-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11032-015-0220-x