Abstract

Paper is a widely used packaging material and is nowadays regaining importance, e.g., as bio-based and biodegradable material. Moreover, new technologies such as polymer–fiber composites, printed electronics and the deep drawing of paper are developing. The process stability and also the resulting quality of paper converting processes such as coating, metallization, printing, and the printing of electronics are highly affected by the hygroexpansion of paper. In order to reduce production instability and to choose and develop paper substrates with ideal characteristics, critical parameters need to be known. This paper offers an extensive overview of those parameters, starting at a molecular and microscopic level with the effect of the constituents and morphology of single fibers, before moving on to paper contents, chemical modifications and additives and finally concluding with paper production and fiber network modification. It was found that the major influences are single fiber sorption, inter-fiber contacts, microfibril angle, fiber morphology (length, width, curliness) and fiber orientation. This review gives new ideas and insights for technologists working in research, development and production optimization of paper-based products.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

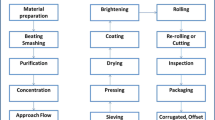

Since 1960 paper production has increased in Europe [1]. In 2015, 106,496 thousand tons of paper was produced in Europe and 407,595 thousand tons worldwide, of which 6% were produced for newsprint, 25% for other graphic applications, 57% for packaging, 9% for hygiene, sanitary and household use and 4% for other applications [2]. In the field of packaging, paper fulfills different purposes. It is used for the protection of the goods (for example, when used as single material for food wrapping), in laminates (for example for carton board liquid packaging), and for secondary packaging (for example boxes). Apart from that, it is used to improve rationalization, by being formed into small load carriers or being used as bar code labels. Moreover, it serves as a tool for communication and marketing, for example as a substrate for printing or printed electronics [3]. In all cases, the performance can be influenced by the hygroexpansion of paper. Hygroexpansion is the dimensional change due to fluctuations of the relative humidity of the surrounding atmosphere which affects the moisture content of the paper [4]. Due to hygroexpansion, laminates and labels can separate, wrinkle or curl, the distance between printing fiducial marks can be altered and the noble appearance of metallized paper can be diminished. As paper is a network of single fibers, the sheet hygroexpansion is mainly influenced by single fiber hygroexpansion. The hygroexpansion here in turn is determined by the polymers that make up the fiber and the ultrastructure of the fiber. This review therefore starts with the effect of the smallest unit—the polymers—before advancing to the fiber, chemical modification and the treatment of fibers during production and concluding with the formation of the fiber network, the effect of paper laminates and an overview of expansion models. Examples of references are given on each structural level.

Scope, aim and demarcation

In this paper, only natural fibers, which are not incorporated into a matrix such as plastics, concrete or else, are taken into account. Creep, curling, wrinkling etc. are mostly excluded. However, they are mentioned where this might help give readers some new ideas or where these properties are somehow related to hygroexpansion (e.g., shrinking [5], wet strength [6], hydroexpansion [7] or creep [8]). Effects related to humidity and dimensional stability have already been partially reviewed [9, 10]. Also, hygroexpansion measurement techniques have been presented [11]. This present review focuses on the factors which trigger hygroexpansion along the production chain, starting from at a molecular level. Regarding expansion coefficients, it has to be taken into account that these coefficients were measured using different methods for different wood species and relate to different factors (e.g., transverse, circumferential, longitudinal strain in relation to moisture content, relative humidity) in fibers or paper sheets. Therefore, expansion coefficients can vary widely and only limited comparisons can be made. In cases where no actual numbers were given in publications, values were estimated from graphs where possible.

Measurement of single fiber and paper sheet hygroexpansion

For the measurement of single fiber hygroexpansion, atomic force microscopy (AFM) [12, 13] and light microscopy [14] in combination with specially designed software for fiber analysis [15, 16] were used to acquire images of fibers and cellulose fibrils. Even 3D images can be obtained by microtomography [17, 18]. In each case, the images were used to measure the fiber dimensions under varying relative humidity, from which the expansion coefficients were calculated. The measurements were mostly done manually or via software.

In principle, the hygroexpansion of single fibers is different in the transversal and longitudinal direction. Additionally, fibers are anisotropically oriented in paper sheets. Consequently, the expansion of paper sheets is higher in the cross direction (CD) than in the machine direction (MD) (see section “Fiber orientation”). Apart from this, paper sheets of course also expand in the out-of-plane direction. In general, measurement techniques for hygroexpansion can be divided into mechanic and optical techniques.

One example of a mechanical system is the Neenah-type hygroexpansiometer. Here, a paper strip is fixed between two clamps, one of which is movable. The contraction and expansion of the sample causes a displacement of the movable clamp. This displacement is monitored via a micrometer, or in newer versions by a linear variable differential transformer [19–21] or a laser scanning position sensor [11, 22, 23]. The disadvantage is that the movable clamp needs to apply some load in order to stretch the sample. If the load is too high, this can falsely increase the measured expansion values.

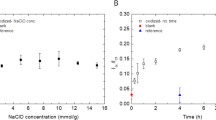

An optical approach is the scanning of paper samples with commercially available high-resolution scanners (1200 dpi). The paper sheets are placed on the scanner and ideally weighed down in order to flatten the sample. After scanning the samples at different humidities, the dimensions can be measured and the expansion calculated [24]. Digital correlation techniques are also used to monitor sheet hygroexpansion [25]. Here, a speckle pattern is applied, for example by spraying color on the paper surface (Fig. 1) [26]. At different relative humidities, images are taken of the paper surface and the varying distances between distinctive points are determined by investigation of the statistical resemblance between two groups of pixel data [27]. This method has the disadvantage that cockling and curling can negatively influence the accuracy of the test method.

Schematic illustration of speckle pattern [28]

A similar method was used by Viguie et al. [29], where 3D maps of the paper sample were obtained by X-ray synchrotron microtomography. The gray shadings of the visible fibrous and porous phases were used as a speckle pattern, based on which the expansion was then calculated as described before. Out-of-plane hygroexpansion can be measured by common thickness measurement methods using, for example, micrometers or profilometers [30].

Measurement values generally relate the hygroexpansion to a certain relative humidity or to a moisture content of the paper. The values can have the units presented in Table 1.

Impacts on the hygroexpansion of the single fibers

Wood fibers have lengths of roughly 1–3 mm and widths of 10–50 µm, with a fiber wall thickness of 1–5 µm [31]. They are assumed to appear as hollow concentric structures comprising the cell wall and the lumen (L) inside [32, 33]. As illustrated in Fig. 2, the cell wall consists of four, and sometimes five, different layers [34]. These layers are commonly called the primary cell wall (P) and the secondary wall consisting of an outer layer (S1), a middle layer (S2) and an inner layer (S3). The middle lamella (ML) surrounds every single wood fiber and strongly binds the fibers to each other. It is hence not perceived as a cell wall layer. The task of the middle lamella is to provide the connection between the cells for transport of biochemicals between the cells [35].

However, the shape of real fibers deviates from this ideal situation. According to their task, cells can be divided into those having a mechanical function, a conducting function and a storing function. In softwood, those functions are fulfilled in the same sequence by latewood tracheids, earlywood tracheids and parenchyma cells. In hardwood those are libriform, sklerenchym cells for mechanical stability, tracheids as conducting cells and parenchyma cells for storing. Accordingly, they vary in shape and size. For papermaking, the tracheids of softwood and libriform cells of hardwood are useful, as they support the mechanical stability of paper due to their length and length-to-width-ratio [36]. Additionally, latewood fibers are shorter, but the cell wall thickness is greater than in earlywood fibers. When fibers are extracted for the paper making process, their shape is additionally altered. Lignin and hemicelluloses are removed, so that the outer surface structure of chemical pulp resembles that of the S1 layer [31]. Apart from that, the lumen collapses during pulping, sheet making and beating of the fibers [32, 37]. This leads to a flattening of the fibers [38], and so sometimes they are modeled as a laminate [37]. More information about the effect of such fiber shape variations can be found in sections “Fiber morphology” “Effect of wood species, parts of the plant, age and compression wood” “Pulp fractions and hornification” “Beating and refining” and “Inter-fiber contact”.

Cell walls are composed of three main polymers: cellulose, hemicelluloses and lignin (see Fig. 3). Cellulose is arranged as lamellar membranes, which are stepwise subdivided into macrofibrils, microfibrils (diameter roughly a multiple of ~3.5 nm), elementary fibrils (~40 cellulose chains, diameter of ~3.5 nm, values highly depending on the specie and measurement technique [39–43]), and the cellulose molecules [39, 40, 44]. (These divisions are, however, not used in a stringent manner in the literature.) As Fig. 3 shows, the microfibril aggregates are assumed to consist of elementary fibrils, which are coated with hemicelluloses and then framed with lignin. However, those polymers are not distributed equally within the cell wall layers. The S layers contain a higher amount of cellulose and hemicelluloses than the P layers. The lignin content is approximately equal among the S layers [34]. The local arrangement of the polymers can be explained as follows based on their chemical affinity [45]: As the more hydrophilic lignin is not compatible with cellulose, hemicelluloses acts like a surfactant, which reduces the free energy and works as an “interfacial boundary region”. For example acetylated side groups turn toward the lignin, whereas hydroxylated side groups orient themselves toward the cellulose (due to having similar solubility parameters, “simulus sub solvuntur”). The steric overlapping of side groups between the layers can lead to an “interpenetrating polymer network [….] of diffuse character” [45]. The importance or unimportance of this inter-layer for the hygroelastic properties is addressed by Wang et al. [46] and Derome et al. [47] as well as in section “Microfibril angle”. The following subsections discuss the effect of the single polymers (cellulose, hemicelluloses and lignin), the microfibril angle, the fiber morphology and sorption on the hygroexpansion of single fibers and paper sheets.

Effects of the polymers in the fiber

As mentioned previously, fibers are constructed out of cellulose, hemicellulose and lignin. The relative amounts and the exact composition of each polymer depend on the plant, specie and part of the plant [48]. Cells generally consist out of approximately 40–50% cellulose, 5–20% lignin, 5–20% hemicelluloses and 8–12% moisture [36, 49]. For wood, average values amount to 45% cellulose, 27% lignin and 23% hemicellulose [50]. The approximate weight fraction of the polymers in the S1/S2/S3 layer is 43/20/14% for lignin, 30/33/36% for hemicellulose and 27/47/50% for cellulose [51].

Taking different sources into account, the moisture contents are about 2.5–7.5% for lignin, 5–10% for cellulose and 10–20% for hemicellulose [52–55]. Other sources state that the amount of absorbed water in a fiber is divided between the hemicellulose, cellulose and lignin in the ratio of 2.6:0:1 [56, 57]. Accordingly, the effect of hemicellulose on the elastic properties is the highest, whereas the impact of lignin and cellulose is only of medium influence [46, 58].

Apart from the weight fraction and the sorption mechanism of the different polymers, the molecular arrangement is reported to play a significant role [45, 59]. Whereas a high concentration of covalent bonds in the cross section of an oriented polymer leads to high stiffness, a high concentration of hydrogen bonds transverse to the polymer backbone leads to a high swelling capacity [34]. This is in line with the description of swelling as “the transport of the swelling agent through a system of pores and channels, leading to some splitting of hydrogen bonds of the cellulose dense, but accessible (meaning most of the time amorphous) regions” [60].

In order to give a better insight into the swelling mechanisms in the single polymers, scientific results on the expansion and water adsorption of cellulose, hemicellulose and lignin are summarized in the following section. Interested readers can find more information about the elastic properties of the single polymers as well as the softening effect of water elsewhere [58, 61, 62].

Hereinafter, findings about the swelling and adsorption of the different polymers are presented, starting with the hemicellulose, followed by cellulose before coming to lignin.

Hygroexpansion of hemicellulose

The exact composition of hemicellulose differs for different plants and parts of plants. Chemically, its main fractions are mannose, xylose, glucose, galactose and arabinose. Compared to cellulose, hemicellulose is branched and has short polymers with a degree of polymerization of only 200 [63, 64]. It has already been mentioned that hemicellulose absorbs the highest amount of water and thus shows the most extensive swelling among the fiber polymers. As swelling is related to the solubility of the constituent in a solvent, the Hansen solubility parameters [65] can be taken into account to estimate the swelling behavior [45]. Due to the high solubility parameters of hemicellulose side groups, it absorbs more water.

Hygroexpansion of cellulose

Cellulose is a hydrophilic glucan polymer, consisting of chains of 1,4-β-bonded anhydroglucose units with a degree of polymerization of 300–10000. These chains enclose alcoholic hydroxyl groups, building intramolecular and intermolecular bonds as well as bonds with ambient hydroxyl groups [48, 66] (see Fig. 4). Cellulose can be subdivided into cellulose I and II as well as α and β conformations, of which cellulose I in the native form. Whereas cellulose I molecular chains are arranged in parallel, cellulose II appears with antiparallel chains. Cellulose Iα and Iβ are composed of extended chains, aligned with the microfibril axis. The α-form has only a single chain with a triclinic unit, and the β-form has two chains in monoclinic arrangement. Cellulose II is the most stable form [66, 67]. Consequently, the high density and ordered supramolecular structure reduce the swelling capacity, although it is highly hygroscopic. Apart from the crystallinity, the chemical surrounding of the cellulose and the processing has influences on the water sorption.

The crystallinity of cellulose appears in different orders, and even amorphous regions (without any order) exist [60, 68]. The exact relative amount of crystalline and amorphous cellulose depends on the species [69]. Compared to lignin and hemicellulose, cellulose is a rather crystalline material and therefore its swelling capability—determined by the amorphous regions—is low and sometimes neglected when talking about fiber hygroexpansion [46, 70, 71] or homogenized with the swelling capability of hemicelluloses [47]. However, only 60–70% of the cellulose in cell wall layers exists in a crystalline form. Thirty to forty percent is amorphous and affected by water molecules [72]. Kocherbitov et al. evaluated the hydration of microcrystalline cellulose (cellulose I and II) and amorphous cellulose. They found that the water sorption increases from cellulose I to cellulose II to amorphous cellulose [73]. During the process of water absorption by amorphous cellulose, water molecules are first of all bound to the O6 and O2 hydroxyl groups of cellulose. Only at higher moisture contents O3 hydroxyl groups and the acetal oxygens attract water molecules. Progressively, the water molecules built clusters before filling capillary channels. The estimated volume hygroexpansion (% vol) of amorphous cellulose was 0.0097% for 0–36% hydration level (m.c.) [74]. Similar is found for different microcrystalline celluloses where a higher crystallinity led to a lower moisture content below 75% r.h. At 75% r.h. crystallinity indexes of 45–95% led to moisture contents of 12–6% m.c., respectively. Above 75% r.h., a rapid increase in moisture content was observed for highly crystalline cellulose powders [55]. However, microfibrillated and whiskered cellulose showed the same sorption isotherm even though they had different crystallinities and morphologies [53]. Contrary to expectations, no clear correlation between the crystallinity index and the hygroexpansion of paper could be found [69]. This might be related to the adverse effects that are reported for cellulose such as expansion during drying and shrinkage during water absorption [75–77].

The expansion and sorption of cellulose not only depend on the crystallinity but also on the surroundings of the cellulose molecules. Counter ions are reported to have a huge effect on the moisture sorption of cellulosic materials containing sulfate and carboxylic groups in different ionic forms [78]. Additionally, the swelling dynamics of cellulose depend on the applied solvents [45, 79]. Moreover, it was observed that the swelling was non-uniform along the fibers and showed some “ballooning” for different solvents [60]. One explanation might be that when the fibrils in the secondary wall swell transversely, the primary wall bursts at distinct spots. In these areas “ballooning” is visible, namely non-uniform swelling along the fibers [80].

Apart from the crystallinity and the chemical surroundings of the cellulose molecules, the processing and the general fiber constitution may have an effect. Such has been shown by Fahlén and Salmén [81], who observed thermally triggered reorganization of cellulose molecules (temperatures between 0 and 225 °C) leading to swelling of cellulose aggregates (18 nm diameter in unprocessed wood, 23 nm in processed wood). Moreover, a decreasing hemicelluloses content is reported to lead to a higher average fibril aggregate size (diameter of 17.9–22.2 nm) due to coalescence of the cellulose microfibrils [82].

Hygroexpansion of lignin

Lignin is a phenolic compound, consisting of the monomers p-coumaryl, coniferyl, and sinapyl alcohols. Lignin gives fibers mechanical stability [48, 83]. As lignin is commonly removed from the fibers in order to reduce paper yellowing, few publications deal with the swelling of lignin.

The sorption isotherm for lignin is very strong dependent on the extraction method. The moisture content at 50% r.h. is ~5% for dioxane lignin, ~9.5% for Klason lignin and ~10% for periodate lignin [84]. Lignin from conifer cuticles is reported to have moisture contents of 2 and 6% at 50% r.h. during adsorption and desorption, respectively [54]. The solubility and swelling of lignin is lowest in water and increases from benzene to methanol, ether and acetone. Constituents of lignin with a lower molecular weight are soluble in a wider range of solvents [85]. Moreover, the fiber swelling increases, as soon as the softening temperature (60–75 °C) has been reached possibly due to movement or flow of the lignin [86]. It was reported that the use of different lignin derivatives (aminated lignin, manganese(III) + lignin, suberin-like lignin) reduces the hygroexpansion of paper from 0.29 to 0.26% (for change of relative humidity from 33 to 66% r.h.) [87]. Apart from the chemical composition, the impact of lignin on the hygroexpansion depends on the microfibril angle in the S2 layer [46]. The combination of a higher lignin content and small microfibril angles in the S2 layer reduces the transverse fiber hygroexpansion [70].

Microfibril angle

The microfibril angle (MFA) is commonly defined as the angle between the longitudinal axis and the microfibril [88] (see Fig. 5). Microfibrils wind helically within the secondary layers. However, the winding direction of the microfibrils differs: usually S1 and S3 wind in the opposite direction of S2 [89]. Microfibrils in S1 and S3 show progressive change of winding direction toward and away from S2, respectively.

In the primary cell wall, there is a random orientation of cellulose microfibrils. In the S1 layer, MFAs of 50°–70° are common, whereas in the S2 layer the MFA is only approximately 5°–30°. In the S3 layer, the MFA is again much higher at around 70° [35]. The MFAs for different species and cell wall layers have been studied in detail [50, 89, 90, 91, 92, 93]. Within their winding direction, microfibrils show a secondary structure. Microfibrils in S1 and S2 appear as a Z-helix or S-helix, whereas in the S2 layer the microfibrils are arranged in a Z-helix [89, 94]. Although the plant species has an influence, the location of growing does not seem to affect the MFA [95]. However, the fiber treatment during paper production is reported to have an effect. Beating increased the MFA from 3°–15° to 12°–32°, whereas drying increased it further to 39°–48° [95].

The effect of the MFA in each layer depends on the thickness of each layer. Some 90% of the mass is concentrated in the S2 layer [96]. For this reason, the S2 layer defines the swelling properties of normal wood to a major degree [93]. The S1 and S3 layers can be thin and therefore have less influence [90]. Consequently, quite often only the S2 layer is taken into account. Marklund and Varna [52] even went one step further and replaced the S1, S2, and S3 layers with one single layer in the analytical model. This did not majorly affect the expansion in the longitudinal and transverse direction at different MFAs. However, Bergander and Salmén [58] evaluated the influence of the MFA depending on the layer thickness of S1 and S3. In the transverse direction, the effect of the layer thickness of S1 and S3 is distinct: by doubling the layer thickness of the S1 layer, the transverse elastic modulus increased by 20% at an MFA of 70°. This shows how important it is to take S1, its thickness, and its MFA into account.

Generally, all publications agree that a higher MFA leads to higher hygroexpansion in the longitudinal direction and lower hygroexpansion in the transverse direction of the fiber [47, 52, 97, 98, 99, 100]. For small MFAs (<30°), the longitudinal shrinkage is a lot smaller (<1%) than the transverse shrinkage (7–9%), but in the region of extremely large MFAs (40°–50°) this relation switches and the longitudinal shrinkage (<8%) is larger than the transverse shrinkage (<4%) [71]. Similarly, Neagu and Gamstedt [34] reported an increase in expansion in the longitudinal direction from about 0–0.3 (exp.) and a decrease from 0.4 to 0.2 (exp.) in the transverse direction for MFAs of 0°–50°. At a higher abstraction level, it is proven that a lower MFA leads to lower shrinkage of paper sheets [101, 96]. For in-plane isotropic sheets, a reduction from ~0.007 to ~0.004 (exp.) for MFAs of ~40° to ~23° was observed, respectively [96].

Apart from the layer thickness and the microfibril angle itself, the effect of the MFA is somewhat constrained by external factors. Likewise, the chemical characteristics of the fiber seem to have an influence on the effect of the MFA, as compression wood showed lower tangential shrinkage (5.94%) than juvenile wood (8.37%) at the same MFA (14.2°) [91]. Also, the degree of fiber restraining appears to have an effect. It was reported that for non-restrained fibers which can rotate freely (compression wood) the longitudinal expansion increased from approximately 0.025–0.4 (exp.) for MFAs of 0°–50°, whereas for restrained fibers (normal wood) the expansion coefficient stays approximately zero for MFAs of 0°–30° and only increases up to ~0.27 for MFAs of 30°–50° [70].

Although the MFA itself is constrained by external factors, it may also actively constrain other processes. Likewise, the contributions of the hemicelluloses and lignin are dependent on the MFA in S2. In the longitudinal direction, both polymers contribute equally until the MFA reaches 20°. In the MFA range from 20° to 40°, the hemicellulose dominates, whereas at MFAs higher than 40°, lignin dominates. In the transverse direction, both polymers contribute equally until the MFA reaches 30°. At higher MFAs, hemicelluloses dominates [46].

Fiber morphology

In general, the ratios of the different geometrical dimensions of fibers are related to paper properties as follows [14] (see Fig. 6):

Microscopic image of fibers [28]

-

Runkel ratio (ratio of fiber cell wall thickness to its lumen): a high ratio leads to stiff fibers with low bonding ability, and to voluminous paper. The ratio should be about 1.

-

Coefficient of flexibility (ratio of lumen width to its fiber diameter): relates to the bonding strength, tensile strength and bursting properties.

-

Relative fiber length (ratio of the fiber length to diameter): correlates with the tearing resistance of paper.

Fiber length and width and cell wall layer thickness

Fiber lengths of different species were determined by Ververis et al. [102] and varied between 0.74 and 2.32 mm. The dimensions also depend on the growing conditions with a lack of watering even improving paper pulp properties [103].

Higher fiber widths lead to higher hygroexpansion (0.12 and 0.20% expansion for a width of 20 and 35 µm, respectively; direction of measurement not indicated) [23]. Uesaka and Moss [101] observed that longer fibers lead to reduced paper hygroexpansion (expansion of ~0.05 to 0.12%exp/%m.c. for fiber lengths of 2.57–0.40 mm, respectively, direction of measurement not indicated). Similarly, Kijima and Yamakawa [104] observed an inverse correlation: they measured an expansion of 0.28 and 0.14% for hardwood fiber lengths of 0.93 and 1.09 mm, respectively. For softwood pulps, the expansions were 0.23 and 0.17% for fiber lengths of 1.88 and 2.62 mm, respectively. This observation was closely linked to the amount of inter-fiber contacts, as described in section “Inter-fiber contact”.

Conversely, a positive correlation between the addition of fines and hygroexpansion was reported (4.4 and 9.6% fines giving an expansion coefficient of 0.13 and 0.165%/%r.h., respectively) [105]. As mentioned in the previous sections, the polymers present in the cell wall and also the MFA affect the expansion of the cell wall layer. However, the importance of the thinner S1 and S2 layer is often questioned. Whereas some researchers emphasize the importance of S1 and S2 [58], or even introduce additional inter-layers between S1/S2 and S2/S3, respectively [46, 106], others even homogenize these layers into one single layer [52] (see section “Microfibril angle”). A correlation between fiber wall thickness and hygroexpansion has been reported to be negative (expansion of ~0.1 to 0.06%exp./%m.c. for fiber wall thicknesses of 2.25–4 µm) [15] or depend on the wall thickness distribution. It was found that a more peaked and wider distribution of fiber wall thickness leads to a higher hygroexpansion [107]. Pulkkinen et al. [15] found that sheet hygroexpansion is higher for fibers with thin walls at low relative humidities (10–50% r.h.) and lower at higher relative humidities (50–90% r.h.).

Fiber curl and twist

Curl often occurs due to mechanical treatments during pulp processing [108] and depends on the relative humidity [17] and plant species [15]. Fiber curl can be described by the curl factor and the shape factor. The curl factor (f) is the ratio between the fiber contour length (c) and the longest dimension of the fiber (d) (f = c/d) (some authors subtract 1 from that value). The shape factor (s) is the ratio between the longest dimension (d) and fiber contour length (c) (s = d/c). Curled fibers, namely having low shape factors of, for example 94.4 and 89.75%, lead to higher hygroexpansion of 0.12 and 0.225%, respectively (approximated values). However, this effect is reduced when the sheets are dried under restraint. This is explained by the reduction of inter-fiber contacts during restrained drying (see section “Density, fiber content and porosity”) [23]. These findings are in accordance with other studies [16, 105]. For different curl factors of 1.17 and 1.37, an increase in expansion of up to ~0.001%/%r.h. was found [105].

Effect of wood species, parts of the plant, age and compression wood

Depending on the specie, plant part, age, and growing conditions, fibers have different sorption isotherms [109, 110] and suitability for papermaking [14, 38, 102, 111]. As mentioned in the previous section, the paper properties are related to the ratios of the different geometrical dimensions of the fibers [14]. These dimensions (fiber length, diameter, and wall thickness) are in turn dependent on the plant watering. If poorly watered, the fiber length, diameter, wall thickness, and Runkel ratio were found to be reduced (except in the bark) [103]. Therefore, it is not surprising that paper sheet hygroexpansion depends on the tree species. In cross direction (CD), values of 0.48 and 0.54% for a humidity increase of 10% r.h. to 90% r.h were found for different species [15]. Generally, hardwood pulps seem to show lower hygroexpansion than softwood pulp (~0.23% expansion for softwood, 0.13% for hardwood, paper density of ~680 kg/m3) [23]. The longitudinal and transverse expansion coefficients are reported to be 0.5–2.7 and 4–8% for compression wood, 1–2 and 5–8% for juvenile wood and 1–1.5 and 6–12% for mature wood [91]. Similarly, Joffre et al. [70] found distinct differences between normal and compression wood tracheids, which can be related to the MFA, lignin content and the cylindrical structure.

Water sorption of single fibers

Paper shows an S-shaped sorption isotherm, indicating multilayer adsorption, and also a hysteresis effect between adsorption and desorption [10]. The moisture content of fibers fluctuates between ~5 and 10% at 50% r.h. [49]. For example, jute, coir and Sitka spruce have higher moisture contents than fibers containing less lignin such as hemp, flax, and cotton [112]. The water uptake of fibers can be explained by various theories such as the surface adsorption theory, solid solution theory, capillary condensation theory, two-phase mechanism, and the pore-size distribution mechanism [113]. However, the exact sorption kinetics as well as the moisture content depends on the species [114], the fiber extraction method, the exact wood constituents, the temperature, the mechanical stress, the previous history of the fibers [113], and on ambient conditions such as the pH, electrolyte concentration, and valency of the counter-ion [115]. Additionally, the swellability of fibers is affected by the charge (water retention values of ~90 and 170% for charges of 50 and 125 µeq/g, respectively, for hardwood pulp). Strongly hydrated nonionic polymers and also the number of anionic groups on the fiber wall affect the swellability of the cell wall layers and the quantity of water entering the fiber [116]. For fibers, it was shown that moisture is adsorbed in the form of clusters to the same relative degree on hydroxyl and carboxyl sites in cellulose and hemicellulose [117]. Ways of influencing the moisture content and moisture sorption kinetics are reviewed below.

Different chemical treatments that influence the sorption isotherms of the fibers have been reported [69, 112, 118, 119, 120]. The treatment of flax fibers with acetic anhydride and styrene reduced the water uptake, whereas silane and maleic anhydride do not have such a positive effect [118]. In contrast, maleic anhydride, acetylation, acrylic acid, and styrene showed a positive effect on the water sorption (i.e. a reduction of the water uptake) for Alfa (Stipa tenacissima) fibers [119]. Crosslinking by periodate slows down the moisture sorption kinetics (m.c. of 9 and 6.5% at 50% r.h. for carbonyl contents per gram fiber of 0 and 1.2 mmol/g, respectively), which leads to a higher dimensional stability [121, 122]. The relevant research teams were able to simulate the sorption isotherms using Langmuir models, Henry’s law and clustering, the Guggenheim–Anderson–de Boer (GAB) model or the Hailwood Horrobin model. Another method that has been found to alter the surface tension—and thereby the water sorption kinetics of fibers and paper—is chemical grafting. This is further described in section “Grafting”.

Chemical modification and additives

The previous section focused on effects that are inherent to the pure fibers. Once the fibers have been extracted, chemical modifications (polyelectrolyte multilayers, crosslinking) or the use of additives (lignin, fillers) can improve the pulp formulation. After paper sheet formation, the main chemical modifications are undertaken by grafting and corona treatment.

Polyelectrolyte multilayers (PEM) and crosslinking

The inter-fiber contact actively influences the wet tensile strength and sheet hygroexpansion (see section “Inter-fiber contact”). The contact area can be altered at a molecular level by polyelectrolyte multilayers (PEM) and crosslinking. Crosslinking can be achieved by oxidation of the fiber and also by a whole range of other reactions.

PEMs are commonly created using a layer-by-layer technique, where cationic and anionic solutions are alternately applied to a surface. These coatings are self-organizing [123]. PEMs made of polyallylamine hydrochloride and polyacrylic acid applied to wood fibers were reported to lead to an increase in the number of fiber–fiber joints and in the number of covalent bonds in the contact area [124]. However, for sheets dried under restraint, the PEM does not have a large influence on hygroexpansion. For sheets dried without restraint, the dimensional change was higher for virgin fibers (~0.5%) than for PEM-treated fibers (~0.35%) for a moisture content of 10%, although the moisture uptake was lower for virgin fibers at a given relative humidity. This was explained by the different dimensions of the contact area in restraint-dried and freely dried sheets and its development under humidity uptake [20, 21]. Another approach was to use dextran as an electrolyte, as its chemical structure is also made up of glucose molecules, just like cellulose. In this process, the cationic acetal dextran is adsorbed on the fiber surface. Then, it is hydrolyzed to convert the acetal groups into reactive aldehyde groups. The crosslinking step is the reaction of aldehyde groups with hydroxyl groups during paper drying. This is shown to have a positive effect on the tensile strength; however, the hygroexpansion was not studied [125].

Apart from the application of PEMs, oxidation is a common method for crosslinking fibers. Almgren et al. [126] measured the hygroexpansion of composites containing crosslinked and non-crosslinked fibers. They found that crosslinking reduced the transverse hygroexpansion from 0.28 to 0.12/% r.h.. A similar reduction was achieved by the application of periodates. Sodium metaperiodate was used to cleave the C2–C3 bond of 1,4-glucans. Consequently, two reactive aldehyde groups are formed and react with other parts of the fiber, for example by hemiacetal linkages. The water sorption and thus the hygroexpansion was reduced by approximately 28% (when the relative humidity was increased from 20 to 85%) [122]. While using the same chemical on kraft fibers, higher hydroexpansion was observed [127]. Similarly, Gimåker lowered the moisture sorption kinetics and reduced the hygroexpansion from 0.34 to 0.22% (for an increase in relative humidity from 50 to 90% r.h.) by periodate oxidation [121]. On Korean traditional paper (Hanji), the application of citric acid was reported to lead to higher dimensional stability [128].

Similarly, Larsson and Wågberg [7] combined a periodate crosslinking process with subsequent application of PEM, consisting of three layers of polyallylamine hydrochloride and two layers of polyacrylic acid. The hydroexpansion under liquid water was observed. It was found that capillary absorption was prevented, but these hydrophobic sheets showed greater expansion. This could be related to the higher moisture content in the upper fiber layers, as all the water is accumulated there.

Apart from oxidation, crosslinking can be achieved by a wide range of chemicals. The crosslinking of fibers with formaldehyde was reported to increase the dimensional stability, but the dimensional stabilization decreased with increasing reaction time [129–131]. Moreover, formaldehyde, maleic acid (also in combination with glycerol), acetylation, etherification, the use of polyethylene glycol and other methods were compared for reducing the swelling of wood fibers. In this study, polyethylene glycol showed the highest anti-swelling efficiency, followed by acetylation and formaldehyde [131] (see also [132, 133]). Alternatives to formaldehyde can be found in the cotton cellulose industry, for example, butanetetracarboxylic acid [134, 135]. The application of diepoxides, dialdehydes, polyacetals, cyclic ethylene ureas was found to reduce hygroexpansion but also the mechanical strength [136]. An increase in inter-fiber bonds thereby increasing wet web strength by 70% was achieved by the following procedure: The fibers were first treated with carboxymethylcellulose. Then, the 1-ethyl-3-[3-(dimethylaminopropyl)] carbodiimide-assisted reaction of carboxyl and amine groups was triggered and finally adipic dihydrazide was used as the crosslinking agent [137]. Elegir et al. [6] used laccase, an enzyme which oxidizes free phenolic lignin moieties. This allowed the crosslinking of lingo-cellulosic fibers and positively affected the wet tensile strength.

Grafting

As mentioned in section “Impacts on the hygroexpansion of the single fibers”, the swelling of the paper sheet and also of the single fibers depends on the water absorbance of the single fibers. By altering the chemical composition of the fiber surface, the water absorbance can be reduced. The chemical composition can be altered by grafting, namely the covalent attachment of monomers to a surface. Two grafting processes are distinguishable [138]: (a) the surface is functionalized with immobilized initiators followed by polymerization with monomers; (b) functionalized monomers react with the backbone of the polymers. In each case it must be kept in mind that only the surface of the fiber or paper sheet is treated, not the bulk. Below is a summary of publications, where different kinds of grafting were used to reduce hygroexpansion, change the water sorption isotherm, or at least increase the water repellency. Interested readers will find in-depth information about the surface treatments of paper in the extensive review by Samyn [139].

A typical application of type a) process is the corona treatment of polymer surfaces to increase the surface tension and substrate wettability. This technique uses corona discharge which forms a highly reactive gas that reacts with polymer surfaces primarily by breakage of H–C bonds [140, 141]. Consequently, polar groups, such as carbonyl and carboxyl groups are produced [141–151]. When this method was applied to paper, aldehyde groups but not carboxyl groups were formed and surprisingly the water sorption decreased slightly. The treatment seemed to trigger the formation of strong bonds which reduced the penetration of water into the paper sheet [152].

An example of type b) process is treatment of the fibers by acetylation or with styrene, acrylic acid, or maleic anhydride. These methods drastically reduced the water sorption (from ~7.5 to 6% at 50% r.h. for styrene treatment) [119]. Similar studies were performed by Alix et al. [118] who tested the effect of maleic anhydride, acetic anhydride, silane and styrene on flax fibers. Once again, styrene treatment showed the strongest effect. In another study, vinyltrimethoxysilane and g-methacryloxypropyltrimethoxysilane were grafted onto paper sheets by cold-plasma discharge. This treatment reduced the surface tension from about 29.3 to almost 0 mN/m [153]. Similar results were achieved by grafting fatty acids (C16, C18, C22) [154]. A reduction of the polar/dispersive part of the surface tension from 20/28 to 3/27 mJ/m2 was reported for a 6 h treatment with C18 [155]. By grafting methyl methacrylate onto fibers of Agave Americana L., the presence of accessible –OH groups was altered, leading to a reduction in moisture uptake from ~7 to ~4% for a graft yield of 0 and 13.6%, respectively, at a relative humidity of 55%. Simultaneously, the swelling was reduced by ~65% [156].

Lignin

Lignin is often removed from the fibers in order to reduce the yellowing of paper. It is then burnt in a recovery boiler to produce steam. However, this process is rather expensive. Therefore, its use as an additive in paper production was tested. It was found that the mechano-sorptive creep can be decreased and wet strength increased [87, 157]. Not only the wet strength but also the hygroexpansion of paper was reduced from 0.29 to 0.26% (for a change in relative humidity of 33 to 66% on in-plane isotropic sheets) by the addition of manganese (III)-lignin and suberin-like lignin derivatives. However, when pulps with increasing lignin contents were used (3–14%), this led to increased hygroexpansion (~0.2 to ~0.23%). This is explained by the simultaneous relative decrease in the amount of cellulose which helps to fixate the fibrous network (see section “Hygroexpansion of cellulose”) [158]. Moreover, a new hydrophobic coating has been developed which consists of lignin with vegetable oil and attains a contact angle with water of 120° [159].

Fillers

Fillers tend to decrease the hygroexpansion due to the inhibition or reduction of inter-fiber bonds [160]. Accordingly, Figueiredo et al. [161] found that the wet expansion under tension is strongly affected by the filler content. The excessive addition of inorganic fillers reduced the paper web dimensional stability in the cross direction (expansion of ~2.4 to ~2.75% for ash contents of ~23 to ~36%). In contrast, Laurell Lyne et al. [160] found that a filler content of 40% reduced the hygroexpansion by 20% in CD, but no difference was observed between clay and chalk. In the machine direction (MD), the expansion was almost the same for filled and unfilled sheets.

Pulp and paper production

The sections “Fiber morphology”, “Effect of wood species, parts of the plant, age and compression wood” and “Water sorption of single fibers” summarized the effects of different wood species. The fiber origin—and the relevant connected chemical composition and morphology of the fibers—play important roles. Other factors that can influence the hygroexpansion are the extraction process, reuse, and mechanical treatment.

Pulp fractions and hornification

When bleached kraft pulp is replaced by high yield pulp, hygroexpansion increases from ~0.074 to ~0.08%/% m.c. at replacements of ≥20% (direction of measurement (MD or CD) not indicated) [27]. Bleached chemo-thermomechanical (BCTM) fibers—which are a type of high yield pulp—were reported to expand more in the transverse direction than kraft pulp (5.4 and 4.1%, respectively, for r.h. in the range of 50–90% r.h.). However, when BCTMP was added to kraft pulp, the paper showed lower expansion. This is explained by the interaction with other factors such as the sheet density, structure, and inter-fiber bonding [162].

In contrast, the addition of up to 20% microfibrillated cellulose increased the hygroexpansion of freely dried sheets from ~0.9 to ~1.8% (for a humidity increase from 33 to 84%). The effect was less pronounced for restraint-dried sheets. The fineness of the additive did not have a major influence [24].

Another fiber fraction that might gain importance in coming years is recycled fiber. In order to reduce the negative environmental impact, the use of recycled fibers is being promoted. However, infinite reuse is not possible [163]. The drying of fibers causes the fibers to shrink and collapse, and the fiber walls even partially coalesce. This process reduces the accessibility for water molecules during absorption. As these surfaces absorb less water, the initial volume and softness cannot be recovered. This process is also considered as “hornification” [164, 165]. Accordingly, there is a linear correlation between the water retention value and the degree of hornification [166]. A detailed insight into the chemical processes during hornification has been given [165, 167]. The collapsing of the fiber and the reduction in water absorbance leads to a decrease in hygroexpansion when such hornified fibers are added to the pulp. The expansion coefficient in the machine direction (MD) was 0.104%/% r.h. for virgin fibers and 0.096%/% r.h for fibers that had undergone hornification. These observations were, however, dependent on the drying conditions (freely or under restraint) [20, 127] (see section “Density, fiber content and porosity”).

Beating and refining

Beating and refining are mechanical processes that are used to adjust the fiber morphology for the papermaking processes. While the word beating is rather used for laboratory scale or older processes, the word refining is used for modern mill equipment. The aim of the process is the straightening, shortening, and/or flexibilization of the fibers. Refining reduces the length, width, and coarseness of the fibers.

Lower fiber coarseness gives a higher contact area between the fibers in the paper sheet [23]. This can be related to the collapse of the lumen, the resulting flattening of the fiber, and the subsequent increase in the contact area (see section “Inter-fiber contact”). Furthermore, it was reported to increase the paper sheet density [168–171]. Both factors led to higher hygroexpansion (see sections “Density, fiber content and porosity” and “Inter-fiber contact”). In contrast, Pulkkinnen et al. [107] reported a negative effect of refining on hygroexpansion due to alteration of the fiber wall thickness. Salmén et al. [105] took two effects into account: The production of fines during beating led to a higher hygroexpansion of freely dried sheets. Additionally, reduced coarseness and curl led to a lower shrinkage during production and thus to lower hygroexpansion. When sheets with curled fibers were dried under restraint, the hygroexpansion was reduced.

Drying

The drying process in the paper machine consists of three different sections, namely the wire section, press section and drying section. The important factor concerning the hygroexpansion is the drying restraints, which are in turn influenced by process parameters such as stretching, drying, and web tension [172].

Concerning the machine parameter side, the three-dimensional deformation of paper sheets during water absorption was shown to be affected by the non-stable drying conditions in the cross direction. The drying shrinkage was found to be higher at the outer sides (~0.8% in CD) and lower in the middle of the web (~0.5% in CD) [25]. A higher shrinkage during drying also leads to higher subsequent hygroexpansion [5, 25, 173]. This can in turn lead to the three-dimensional deformation of the paper web. Such imperfections induce residual stresses in the paper web which must not be neglected when modeling the three-dimensional deformation of paper sheets [174].

Moreover, the web tension during drying was found to influence the hygroexpansion. The lower the moisture content is, until when the paper is dried under restraint, the lower the observed hygroexpansion. For example, the hygroexpansion was ~0.3, ~0.2 and ~0.15%, when the sheet was dried under restraint down to a relative humidity of 90, 50 and 16%, respectively [175]. This was also confirmed by other researchers. The higher the degree of restraining during drying, the lower is the hygroexpansion (e.g., 2.11% for unrestrained sheets, 0.73% when 4% shrinkage was allowed during drying, for an increase in relative humidity from 30 to 90%, direction of measurement not indicated). When the web was additionally stretched in cross direction, hygroexpansion was further reduced. [173]. Apart from stretching during drying, the drying itself also plays an important role. When paper was dried with superheated steam at 320 °C, the hygroexpansion coefficient was reduced by 15%. This was reasoned as being due to the thermal softening of lignin [176].

Fiber network

The dimensional stability of fiber networks is directly and/or indirectly related to the effect of moisture content. As already described, the changes in the dimensions of single fibers are basically due to their physicochemical interaction with water [12]. In addition, the expansion of the whole fiber network depends on the interaction of the fibers with each other.

Single fiber hygroexpansion

As explained in section “Measurement of single fiber and paper sheet hygroexpansion”, fibers show higher expansion in the transverse direction due to the longitudinal orientation of the polymer chains. Moreover expansion coefficients of the polymers were summarized. The dimensions of the whole fiber were found to increase by 0.10 to 0.15/ % m.c. in the transverse direction [30], by 0.17strain/%r.h. in transverse direction and 0.014strain/%r.h. in longitudinal direction [18], by 1.9–3.3% in the transverse direction, by 2.3–3.2% in the longitudinal direction, by 14.5–18.2% in area and by 12.4–17.3% in height in humidity cycles of 50–78–21% [13]. Apart from the arrangement of the polymers, another explanation for the anisotropic swelling of fibers was the “reinforced matrix hypothesis” [71, 177, 178]. In this hypothesis, the lignin-hemicellulosic matrix is assumed to shrink isotropically and to work like a skeleton in the secondary wall, whereas the cellulose microfibrils are assumed not to shrink during desorption. As a result, the shrinking of the whole fiber is assumed to be anisotropic. In order to link the single fiber hygroexpansion to the sheet hygroexpansion, Heyden, Gustafsson [179] and Uesaka [4] introduced stress transfer factors that describe the efficiency of stress transfer in the network. Simulations successfully reproduced the measured hygroexpansion values. They observed that the expansion in the cross direction (CD) depends on the fiber orientation, stress transfer, and thus on inter-fiber bonding. In contrast, the expansion in the machine direction (MD) is largely determined by the expansion of the single fibers in the longitudinal direction [4]. An additional effect worth mentioning is that the external surface area of the paper decreases between 0 and 65% r.h. when the fibers expand, most probably due to relaxation processes of the fibers [180].

Fiber orientation

Fiber orientation influences many important properties of fiber-based materials. Techniques for fiber orientation measurement have been proposed [181, 182], and the mechanical properties as a function of the fiber direction have been evaluated [183, 184].

Due to the sheet production process, fibers are mostly aligned in the machine direction (MD) (Fig. 7). As already explained, the expansion of single fibers is higher in the transverse direction than in the longitudinal direction. The expansion of paper in cross direction (CD) is up to 7 times higher than in the machine direction (MD) [25, 161, 185, 186]. However, fibers are not 100% parallel in reality and the orientation is determined by several variables of the papermaking process. This is why the hygroexpansion increases in the cross direction (CD) and decreases in the machine direction (MD) with increasing degree of orientation [4, 179]. In cases where there is no orientation, namely the fiber orientation is in-plane isotropic, the sheet hygroexpansion correlates with the transverse fiber expansion in both directions [5].

Apart from the sheet hygroexpansion, the fiber orientation also affects the three-dimensional deformation of paper. Depending on the fiber orientation, samples show a larger twist when they are cut in the cross direction (CD) than in the machine direction (MD) [188]. Additionally, irregularities in fiber orientations which can arise due to cross flows of the jet from the head box in the paper machine can result in waviness (wavelengths 4–5 cm) [189]. Likewise, a higher disorder of local fiber orientation leads to more cockling [190, 191].

Density, fiber content and porosity

Basically, the three parameters density, fiber content and porosity describe each other. The more fibers are present in a defined volume, the higher the density and the lower the porosity.

Concerning the effect of pores on hygroexpansion, different models have been proposed. For low density sheets, it is reported that pores partially compensate the expansion of the fibers, namely the fibers use the empty space for expansion, so that the pore volume decreases while the fiber volume increases. Thus, the overall volume of the paper sheet is affected only to a minor degree. For high density sheets, the fibers seem to expand, whereas the voids between the fibers stay constant [29]. On the other side, one theory states that voids do not keep their size but seem to expand during water uptake (just like voids in metal expand during thermal treatment) and thus enhance hygroexpansion in freely dried paper. For papers dried under restraint, the void expansion is reported to be equal to the overall expansion [76].

A higher density is generally reported to increase hygroexpansion. This was stated as being due to the increased inter-fiber contact (see section “Inter-fiber contact”) and the effects of pore volume [23, 29, 105, 192, 193]. However, the effect of the density is greater in freely dried sheets than in sheets dried under restraint [105]. Additionally, the hygroexpansion is more affected by drying restraints when the solid content is high [175]. For dry solid contents from 55 to 100%, an increase in hygroexpansion from ~0.04 to ~0.16 for softwood freely dried pulp was reported [193].

Inter-fiber contact

Inter-fiber bonds are contact areas between different fibers (see Fig. 8) and can be observed by X-ray microtomography [194]. When fibers swell due to moisture absorption, stresses arise at inter-fiber bonds [195, 196]. This topic has relevance to sections “Fiber curl and twist”, “Polyelectrolyte multilayers (PEM) and crosslinking”, “Fillers”, “Beating and refining”, and “Fiber orientation” because contact areas are typically dependent on fiber orientation, fiber geometry, and also on the fiber content, namely the density of the material [197]. Also, the contact area can be increased by the application of humidity/wetness and pressure. With higher humidity, the hardness of fibers decreases and thus fiber bond formation via hydrogen bonds increases. To maintain this in the dry state, the fibers need to deform plastically [198, 199]. This can be achieved by the collapse of the fiber lumen during beating [32]. Apart from wetting and softening, the interaction between fibers can be increased by hornification, crosslinking or oxidation (addressed in sections “Chemical modification and additives” and “Pulp and paper production”).

Fibrous network [28]

Marulier et al. [197] found up to 45 inter-fiber contacts/mm for fiber lengths of 0–0.5 mm. For fiber lengths >0.5 mm, the number of contacts decreases to about 30 contacts/mm. A positive, partially almost linear correlation between inter-fiber contact or density and hygroexpansion has been reported [5, 23, 76, 105, 200]. In a non-isotropic fiber network, the hygroexpansion consists of two parts: expansion in the machine direction (MD) and the cross direction (CD). The expansion in the cross direction (CD) is mainly affected by fiber orientation (see section “Fiber orientation”) and increases with the degree of inter-fiber bonding [4, 5, 200]. However, the effect of inter-fiber contacts depends on the fiber orientation and increases depending on the degree of drying restraint [21, 201]. Regarding the assumption that more inter-fiber contacts lead to a higher hygroexpansion, contrary effects for hydroexpansion have been observed. Sheets of microfibrillated cellulose (i.e. without fiber joints) and ordinary sheets showed the same expansion. It was concluded that the expansion of the paper sheet is linked to the expansion of the fiber wall and that fiber joints hardly influence the hydroexpansion [7].

Laminates

The term laminate here describes a multilayer material, consisting of paper and one or more additional polymeric layers. Although quite a view patents have been published claiming improved dimensional stability of paper by the application of coatings (see for example [202–204]), only one publication was found, dealing with the effect of polymeric coatings on the hygroexpansion of paper. It was reported that the coating of paper with polyethylene reduces the hygroexpansion in the machine direction (MD) from for example 0.0036%/% r.h. to 0.0023%/% r.h. [205].

Models

Lots of work has been put into the development of various models describing the hygroexpansion of fibers, wood, paper sheets, paper polymer multilayers or fibers in a polymer matrix. Some of the conclusions drawn in the relevant publications have been mentioned in the previous sections. It is outside of the scope of this review to compare these models. However, an overview is given of the relevant literature (Table 2).

Conclusions

This review shows that the hygroexpansion of fibers and paper is a property that is affected by and affects many other properties. From the overview in Fig. 9, it can be seen that the main factors are single fiber hygroexpansion and the inter-fiber contacts. For both factors, various methods have been described for influencing the hygroexpansion. These methods are mainly of relevance for paper producers. Only grafting, corona treatment, and coating with polymers (laminates) are of relevance for paper converters. Even the paper producers have little active influence over fiber specific characteristics such as the expansion of the individual polymers, fiber curl and twist, or microfibril angle. The easiest ways to alter the hygroexpansive properties are the drying, the application of polyelectrolyte multilayers, fillers, fiber orientation, density, fiber content and pore size, grafting, and the use of specific pulp fractions such as recycled hornified fibers.

Interplay of factors affecting hygroexpansion [28]

References

European Forest Sector Outlook Study (2005). United Nations Publications

Papierfabriken VD (2017) Papier 2017, Annual Report

Tobjörk D, Österbacka R (2011) Paper electronics. Adv Mater 23(17):1935–1961. doi:10.1002/adma.201004692

Uesaka T (1994) General formula for hygroexpansion of paper. J Mater Sci 29(9):2373–2377. doi:10.1007/BF00363429

Sampson WW, Yamamoto J (2011) The drying shrinkage of cellulosic fibres and isotropic paper sheets. J Mater Sci 46(2):541–547. doi:10.1007/s10853-010-5006-2

Elegir G, Bussini D, Antonsson S, Lindström ME, Zoia L (2007) Laccase-initiated cross-linking of lignocellulose fibres using a ultra-filtered lignin isolated from kraft black liquor. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 77(4):809–817. doi:10.1007/s00253-007-1203-6

Larsson PA, Wågberg L (2010) Diffusion-induced dimensional changes in papers and fibrillar films: influence of hydrophobicity and fibre-wall cross-linking. Cellulose 17(5):891–901. doi:10.1007/s10570-010-9433-7

Considine JM, Stoker DL, Laufenberg TL, Evans JW (1994) Compressive creep-behavior of corrugating components affected by humid environment. Tappi J 77(1):87–95

Uesaka T (1991) Dimensional stability of paper—upgrading paper performance in end use. J Pulp Pap Sci 17(2):J39–J46

Haslach HW (2000) The moisture and rate-dependent mechanical properties of paper: a review. Mech Time Depend Mater 4(3):169–210. doi:10.1023/A:1009833415827

Pulkkinen I, Fiskari J, Alopaeus V (2009) The effect of sample size and shape on the hygroexpansion coefficient—a study made with advanced methods for hygroexpansion measurement. Technical Association of the Pulp and Paper Industry of Southern Africa, pp 26–33

Lee JM (2007) An atomic force microscopy study of the local hygro-expansion behavior of cellulose microfibrils. Dissertation, North Carolina State University, Releigh

Lee JM, Pawlak JJ, Heitmann JA (2012) Dimensional and hygroexpansive behaviors of cellulose microfibrils (MFs) from kraft pulp-based fibers as a function of relative humidity. Holzforschung, pp 66

Kiaei M, Tajik M, Vaysi R (2014) Chemical and biometrical properties of plum wood and its application in pulp and paper production. Maderas Ciencia y tecnología 16(3):313–322. doi:10.4067/S0718-221x2014005000024

Pulkkinen I, Fiskari J, Alopaeus V (2008) The effect of hardwood fiber morphology on the hygroexpansivity of paper. BioResources 4(1):126–141

Pulkkinen I (2010) From eucalypt fiber distributions to technical properties of paper. Dissertation, Aalto University, Espoo

Toungara M, Latil P, Dumont PJJ, du Roscoat SR, Orgéas L, Joffre T, Passas R (2014) 3D Observation of the hygroexpansion of wood fibres. In: MécaMat Grenoble

Joffre T, Isaksson P, Dumont PJJ, Roscoat SRd, Sticko S, Orgéas L, Gamstedt EK (2016) A method to measure moisture induced swelling properties of a single wood cell. Exp Mech 56(5):723–733. doi:10.1007/s11340-015-0119-9

Mark RE, Habeger C, Borch J, Lyne MB (2001) Handbook of physical testing of paper: volume 1, vol 1. CRC Press, Boca Raton

Larsson PA (2010) Hygro-and hydroexpansion of paper: influence of fibre-joint formation and fibre sorptivity. Dissertation, KTH Royal Institute of Technology, Stockholm

Larsson PA, Wågberg L (2008) Influence of fibre–fibre joint properties on the dimensional stability of paper. Cellulose 15(4):515–525. doi:10.1007/s10570-008-9203-y

Ikuta S, Hitosugi F (1996) New expansimeter for paper sample. In: Pulp and paper research conference, Tokyo, Japan, pp 70–73

Antonsson S, Mäkelä P, Fellers C, Lindström ME (2009) Comparison of the physical properties between hardwood and softwood pulps. Nord Pulp Pap Res J 24(4):409–414. doi:10.3183/NPPRJ-2009-24-04-p409-414

Manninen M, Kajanto I, Happonen J, Paltakari J (2011) The effect of microfibrillated cellulose addition on drying shrinkage and dimensional stability of wood-free paper. Nord Pulp Pap Res J 26(3):297–305

Mendes AHT, Kim HY, Ferreira PJT, Park SW (2012) The importance of the measurement of paper differential CD shrinkage. O PAPEL 73(2):45–50

Lif JO, Fellers C, Soremark C, Sjodahl M (1995) Characterizing the in-plane hygroexpansivity of paper by electronic speckle photography. J Pulp Pap Sci 21(9):J302–J308

Barquin A (2011) Effect of high yield pulp on the dimensional stability of wood-free paper for inkjet printing applications. Master Thesis, University of Toronto, Toronto

Lindner M (2016) Nutzung des elektrischen Oberflächenwiderstandes zur Abschätzung der Hygroexpansion, Substratrauheit und Gasbarriere von aufgedampften Aluminiumschichten auf Papier und Folie. Fraunhofer IVV, Freising

Viguie J, Dumont PJJ, Mauret E, du Roscoat SR, Vacher P, Desloges I, Bloch JF (2011) Analysis of the hygroexpansion of a lignocellulosic fibrous material by digital correlation of images obtained by X-ray synchrotron microtomography: application to a folding box board. J Mater Sci 46(14):4756–4769. doi:10.1007/s10853-011-5386-y

Neagu RC, Gamstedt EK, Lindström M (2005) Influence of wood-fibre hygroexpansion on the dimensional instability of fibre mats and composites. Compos A Appl Sci Manuf 36(6):772–788. doi:10.1016/j.compositesa.2004.10.023

Chinga-Carrasco G (2011) Cellulose fibres, nanofibrils and microfibrils: the morphological sequence of MFC components from a plant physiology and fibre technology point of view. Nanoscale Res Lett 6(1):417. doi:10.1186/1556-276x-6-417

Yamauchi T (2007) A method to determine lumen volume and collapse degree of pulp fibers by using bottleneck effect of mercury porosimetry. J Wood Sci 53(6):516–519. doi:10.1007/s10086-007-0895-7

Wardrop AB, Preston RD (1947) Organisation of the cell walls of tracheids and wood fibres. Nature 160(4078):911–913

Neagu RC, Gamstedt EK (2007) Modelling of effects of ultrastructural morphology on the hygroelastic properties of wood fibres. J Mater Sci 42(24):10254–10274. doi:10.1007/s10853-006-1199-9

Wiedenhoeft AC, Miller RB (2005) Structure and Function of Wood. In: Wood handbook—wood as an engineering material. United States Department of Agriculture Forest Service, Madison, Wisconsin, p 9

Blechschmidt J (2010) Taschenbuch der Papiertechnik: mit 85 Tabellen. Hanser

Salmén L, de Ruvo A (2007) A model for the prediction of fiber elasticity. Wood Fiber Sci 17(3):336–350

Reme PA (2000) Some effects of wood characteristics and the pulping process on mechanical pulp fibres. Dissertation, Norwegian University of Science and Technology, Trondheim

Heyn A (1969) The elementary fibril and supermolecular structure of cellulose in soft wood fiber. J Ultrastruct Res 26(1–2):52–68. doi:10.1016/s0022-5320(69)90035-5

Meier H (1962) Chemical and morphological aspects of the fine structure of wood. Pure Appl Chem 5(1–2):37–52

Jakob HF, Fratzl P, Tschegg SE (1994) Size and arrangement of elementary cellulose fibrils in wood cells: a small-angle X-ray scattering study of picea abies. J Struct Biol 113(1):13–22. doi:10.1006/jsbi.1994.1028

Jakob H, Fengel D, Tschegg S, Fratzl P (1995) The elementary cellulose fibril in Picea abies: comparison of transmission electron microscopy, small-angle X-ray scattering, and wide-angle X-ray scattering results. Macromolecules 28(26):8782–8787. doi:10.1021/ma00130a010

Zhang Y, Chen X, Liu J, Gao P, Shi D, Pang S (1997) Size and arrangement of elementary fibrils in crystalline cellulose studied with scanning tunneling microscopy. J Vac Sci Technol Microelectron Nanometer Struct Process Meas Phenom 15(4):1502–1505. doi:10.1116/1.589483

Muhlethaler K (1960) Die Feinstruktur der Zellulosemikrofibrillen. Beih Z Schweiz Forstver 30:55–64

Hansen CM, Björkman A (1998) The ultrastructure of wood from a solubility parameter point of view. Holzforschung Int J Biol Chem Phys Technol Wood 52(4):335–344. doi:10.1515/hfsg.1998.52.4.335

Wang NL, Liu WY, Lai JP (2014) An attempt to model the influence of gradual transition between cell wall layers on cell wall hygroelastic properties. J Mater Sci 49(5):1984–1993. doi:10.1007/s10853-013-7885-5

Derome D, Rafsanjani A, Hering S, Dressler M, Patera A, Lanvermann C, Sedighi-Gilani M, Wittel FK, Niemz P (2013) The role of water in the behavior of wood. J Build Phys 36(4):1744259112473926. doi:10.1177/1744259112473926

Mohanty AK, Misra M, Hinrichsen G (2000) Biofibres, biodegradable polymers and biocomposites: an overview. Macromol Mater Eng 276–277(1):1–24. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1439-2054(20000301)276:1<1:AID-MAME1>3.0.CO;2-W

Saheb DN, Jog JP (1999) Natural fiber polymer composites: a review. Adv Polym Technol 18(4):351–363. doi:10.1002/(Sici)1098-2329(199924)18:4<351:Aid-Adv6>3.0.Co;2-X

Oksman K, Mathew AP, Bismarck A (2014) Handbook of green materials, volume 5: biobased composite materials, their processing properties and industrial applications. World Scientific Publishing Company, Singapore

Panshin AJ, De Zeeuw C (1980) Textbook of wood technology: structure, identification, properties, and uses of the commercial woods of the United States and Canada, vol Bd. 1. McGraw-Hill, New York

Marklund E, Varna J (2009) Modeling the hygroexpansion of aligned wood fiber composites. Compos Sci Technol 69(7–8):1108–1114. doi:10.1016/j.compscitech.2009.02.006

Belbekhouche S, Bras J, Siqueira G, Chappey C, Lebrun L, Khelifi B, Marais S, Dufresne A (2011) Water sorption behavior and gas barrier properties of cellulose whiskers and microfibrils films. Carbohyd Polym 83(4):1740–1748. doi:10.1016/j.carbpol.2010.10.036

Reina JJ, Domínguez E, Heredia A (2001) Water sorption–desorption in conifer cuticles: the role of lignin. Physiol Plant 112(3):372–378. doi:10.1034/j.1399-3054.2001.1120310.x

Mihranyan A, Llagostera AP, Karmhag R, Strømme M, Ek R (2004) Moisture sorption by cellulose powders of varying crystallinity. Int J Pharm 269(2):433–442. doi:10.1016/j.ijpharm.2003.09.030

Persson K (2000) Micromechanical modelling of wood and fibre properties. Lund University, Lund

Cave I (1978) Modelling moisture-related mechanical properties of wood part I: properties of the wood constituents. Wood Sci Technol 12(1):75–86

Bergander A, Salmén L (2002) Cell wall properties and their effects on the mechanical properties of fibers. J Mater Sci 37(1):151–156. doi:10.1023/A:1013115925679

Salmen L, Olsson AM, Stevanic JS, Simonovic J, Radotic K (2012) Structural organisation of the wood polymers in the wood fibre structure. BioResources 7(1):521–532

Cuissinat C, Navard P (2006) Swelling and dissolution of cellulose part 1: free floating cotton and wood fibres in N-methylmorpholine-N-oxide–water mixtures. Macromol Symp 244(1):1–18. doi:10.1002/masy.200651201

Salmén L (2004) Micromechanical understanding of the cell-wall structure. CR Biol 327(9–10):873–880. doi:10.1016/j.crvi.2004.03.010

Nakamura KI, Wada M, Kuga S, Okano T (2004) Poisson’s ratio of cellulose Iβ and cellulose II. J Polym Sci Part B Polym Phys 42(7):1206–1211. doi:10.1002/polb.10771

Neville AC (1993) Biology of fibrous composites: development beyond the cell membrane. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Jacobs A, Dahlman O (2001) Characterization of the molar masses of hemicelluloses from wood and pulps employing size exclusion chromatography and matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry. Biomacromol 2(3):894–905

Hansen CM (2012) Hansen solubility parameters: a user’s handbook. CRC Press, Boca Raton

Credou J, Berthelot T (2014) Cellulose: from biocompatible to bioactive material. J Mater Chem B 2(30):4767–4788. doi:10.1039/c4tb00431k

Mark RE, Borch J (2001) Handbook of physical testing of paper, vol Bd. 1. Taylor & Francis, Milton Park

Wüstenberg T (2013) Cellulose und cellulosederivate: grundlagen, Wirkungen und Applikationen. Behr’s Verlag DE, Humburg

Pulkkinen I, Fiskari J, Alopaeus V (2009) CPMAS 13C NMR analysis of fully bleached eucalypt pulp samples: links to handsheet hygroexpansivity and strength properties. J Appl Sci 9(22):3991–3998

Joffre T, Neagu RC, Bardage SL, Gamstedt EK (2014) Modelling of the hygroelastic behaviour of normal and compression wood tracheids. J Struct Biol 185(1):89–98. doi:10.1016/j.jsb.2013.10.014

Yamamoto H, Sassus F, Ninomiya M, Gril J (2001) A model of anisotropic swelling and shrinking process of wood—part 2. A simulation of shrinking wood. Wood Sci Technol 35(1–2):167–181

Alince B (2002) Porosity of swollen pulp fibers revisited. Nord Pulp Pap Res J 17(1):71–73. doi:10.3183/NPPRJ-2002-17-01-p071-073

Kocherbitov V, Ulvenlund S, Kober M, Jarring K, Arnebrant T (2008) Hydration of microcrystalline cellulose and milled cellulose studied by sorption calorimetry. J Phys Chem B 112(12):3728–3734. doi:10.1021/jp711554c

Mazeau K (2015) The hygroscopic power of amorphous cellulose: a modeling study. Carbohyd Polym 117:585–591. doi:10.1016/j.carbpol.2014.09.095

Chen WC, Tejado A, Alam MN, van de Ven TG (2015) Hydrophobic cellulose: a material that expands upon drying. Cellulose 22(4):2749–2754. doi:10.1007/s10570-015-0645-8

Salmén L, Fellers C (1989) The nature of volume hydroexpansivity of paper. J Pulp Pap Sci 15(2):J63–J65

Roseveare WE (1947) Contributions to the physics of cellulose fibres. P. H. HERMANS. Elsevier, New York-Amsterdam, 1946. In English. 221 pp. Price $4.00. J Polym Sci 2(3):354. doi:10.1002/pol.1947.120020321

Berthold J, Desbrieres J, Rinaudo M, Salmén L (1994) Types of adsorbed water in relation to the ionic groups and their counter-ions for some cellulose derivatives. Polymer 35(26):5729–5736

Uetani K, Yano H (2012) Zeta potential time dependence reveals the swelling dynamics of wood cellulose nanofibrils. Langmuir 28(1):818–827. doi:10.1021/la203404g

Cuissinat C, Navard P (2008) Swelling and dissolution of cellulose, part III: plant fibres in aqueous systems. Cellulose 15(1):67–74. doi:10.1007/s10570-007-9158-4

Fahlén J, Salmén L (2003) Cross-sectional structure of the secondary wall of wood fibers as affected by processing. J Mater Sci 38(1):119–126. doi:10.1023/A:1021174118468

Wan J, Wang Y, Xiao Q (2010) Effects of hemicellulose removal on cellulose fiber structure and recycling characteristics of eucalyptus pulp. Bioresour Technol 101(12):4577–4583. doi:10.1016/j.biortech.2010.01.026

Roberts V, Stein V, Reiner T, Lemonidou A, Li X, Lercher JA (2011) Towards quantitative catalytic lignin depolymerization. Chem Eur J 17(21):5939–5948. doi:10.1002/chem.201002438

Cousins WJ (1976) Elastic-modulus of lignin as related to moisture-content. Wood Sci Technol 10(1):9–17

Schuerch C (1952) The solvent properties of liquids and their relation to the solubility, swelling, isolation and fractionation of lignin. J Am Chem Soc 74(20):5061–5067. doi:10.1021/ja01140a020

Eriksson I, Haglind I, Lidbrandt O, Sahnén L (1991) Fiber swelling favoured by lignin softening. Wood Sci Technol 25(2):135–144. doi:10.1007/bf00226813

Antonsson S (2007) The Use of lignin derivatives to improve selected paper properties. Dissertation, Royal Institute of Technology, Stockholm

Barnett JR, Bonham VA (2004) Cellulose microfibril angle in the cell wall of wood fibres. Biol Rev 79(2):461–472. doi:10.1017/S1464793103006377

Meylan BA, Butterfield BG (1978) Helical orientation of the microfibrils in tracheids, fibres and vessels. Wood Sci Technol 12(3):219–222. doi:10.1007/BF00372867

Andersson S, Serimaa R, Torkkeli M, Paakkari T, Saranpää P, Pesonen E (2000) Microfibril angle of Norway spruce [Picea abies (L.) Karst.] compression wood: comparison of measuring techniques. J Wood Sci 46(5):343–349. doi:10.1007/bf00776394

Leonardon M, Altaner CM, Vihermaa L, Jarvis MC (2010) Wood shrinkage: influence of anatomy, cell wall architecture, chemical composition and cambial age. Eur J Wood Wood Prod 68(1):87–94. doi:10.1007/s00107-009-0355-8

Reiterer A, Jakob HF, Stanzl-Tschegg SE, Fratzl P (1998) Spiral angle of elementary cellulose fibrils in cell walls of Picea abies determined by small-angle X-ray scattering. Wood Sci Technol 32(5):335–345. doi:10.1007/bf00702790

Sahlberg U, Salmén L, Oscarsson A (1997) The fibrillar orientation in the S2-layer of wood fibres as determined by X-ray diffraction analysis. Wood Sci Technol 31(2):77–86. doi:10.1007/bf00705923

Donaldson L, Xu P (2005) Microfibril orientation across the secondary cell wall of Radiata pine tracheids. Trees 19(6):644–653. doi:10.1007/s00468-005-0428-1

Vainio A, Sirvio M, Paulapuro H (2007) Observations on the microfibril angle of Finnish papermaking fibres. In: 61st Appita annual conference and exhibition, Gold Coast, Australia 6–9 May 2007: Proceedings, 2007. Appita Inc., p 397

Courchene CE, Peter GF, Litvay J (2006) Cellulose microfibril angle as a determinant of paper strength and hygroexpansivity in Pinus taeda L. Wood Fiber Sci 38(1):112–120

Burgert I, Frühmann K, Keckes J, Fratzl P, Stanzl-Tschegg S (2004) Structure–function relationships of four compression wood types: micromechanical properties at the tissue and fibre level. Trees 18(4):480–485. doi:10.1007/s00468-004-0334-y

Eder M, Jungnikl K, Burgert I (2008) A close-up view of wood structure and properties across a growth ring of Norway spruce (Picea abies [L] Karst.). Trees 23(1):79–84. doi:10.1007/s00468-008-0256-1

Gindl W, Gupta HS, Schöberl T, Lichtenegger HC, Fratzl P (2004) Mechanical properties of spruce wood cell walls by nanoindentation. Appl Phys A 79(8):2069–2073. doi:10.1007/s00339-004-2864-y

Jäger A, Bader T, Hofstetter K, Eberhardsteiner J (2011) The relation between indentation modulus, microfibril angle, and elastic properties of wood cell walls. Compos A Appl Sci Manuf 42(6):677–685. doi:10.1016/j.compositesa.2011.02.007

Uesaka T, Moss C (1997) Effects of fibre morphology on hygroexpansivity of paper—a micromechanics approach. Fund Papermak Mater 1:663–679

Ververis C, Georghiou K, Christodoulakis N, Santas P, Santas R (2004) Fiber dimensions, lignin and cellulose content of various plant materials and their suitability for paper production. Ind Crops Prod 19(3):245–254. doi:10.1016/j.indcrop.2003.10.006

Ogbonnaya CI, Roy-Macauley H, Nwalozie MC, Annerose DJM (1997) Physical and histochemical properties of kenaf (Hibiscus cannabinus L.) grown under water deficit on a sandy soil. Ind Crops Prod 7(1):9–18. doi:10.1016/S0926-6690(97)00034-4

Kijima T, Yamakawa I (1978) Effect of beating condition on shrinkage during drying. Jpn Tappi J 32(12):722–727

Salmén L, Boman R, Fellers C, Htun M (1987) The implications of fiber and sheet structure for the hygroexpansivity of paper [curl, shrinkage, beating, fines]. Nordic Pulp Pap Res J (Sweden) 4

Wang N, Liu W, Peng Y (2013) Gradual transition zone between cell wall layers and its influence on wood elastic modulus. J Mater Sci 48(14):5071–5084. doi:10.1007/s10853-013-7295-8