Abstract

Azobenzene derivatives due to their photo- and electroactive properties are an important group of compounds finding applications in diverse fields. Due to the possibility of controlling the trans–cis isomerization, azo-bearing structures are ideal building blocks for development of e.g. nanomaterials, smart polymers, molecular containers, photoswitches, and sensors. Important role play also macrocyclic compounds well known for their interesting binding properties. In this article selected macrocyclic compounds bearing azo group(s) are comprehensively described. Here, the relationship between compounds’ structure and their properties (as e.g. ability to guest complexation, supramolecular structure formation, switching and motion) is reviewed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The year 2017 appears to be a very special for supramolecular chemistry. 50 years ago Charles Pedersen [1] published papers describing the syntheses and completely untypical and unknown until that time intriguing complexing properties of macrocyclic polyethers, i.e. crown ethers [2, 3]. The discovery turned out to be a milestone in chemistry that changed the whole chemical world, gave new fascination and opened up new perespectives for science and technology. Crown ethers are excellent example of unexpected discovery that gained worldwide fame. Since discovery of crown ethers, many their applications have been developed, for example in chromatography [4, 5], sample preparations [6], catalysis [7,8,9], and chemical sensing [10].

Macrocyclic compounds had entered the laboratories all over the world, in particular after the discovery of macrocycles containing oxygen and nitrogen electron donors, being the base for three dimensional cryptands, synthesized and studied by Lehn [11, 12] and spherands, obtained and investigated by Cram [13,14,15,16]. All these discoveries initiated host–guest [17, 18] and supramolecular chemistry [19,20,21,22]. For their achievements Pedersen [23], Cram [18] and Lehn [20] were honored in 1987 with a Nobel Prize. The Nobel Prize in Chemistry 2016 was awarded to: Jean-Pierre Sauvage, Sir J. Fraser Stoddart and Ben L. Feringa “for the design and synthesis of molecular machines” [24,25,26], which have close relationship with the above mentioned branches of chemistry.

A year after Pedersen’s publication on crown ethers and their unique metal cation binding abilities, Park and Simmons published work on macrobicyclic amines i.e. catapinands, the first anion receptors [27,28,29]. Since that time supramolecular chemistry of anions for many years seemed to be almost forgotten, but last two decades were a renaissance of anion recognition studies [30,31,32,33].

Within the last 50-years a lot of macrocyclic compounds of sophisticated structures have been synthesized and investigated [34]. The skeleton of the vast majority of macrocyles can be more or less easily modified by introducing functional groups, which bring about additional chemical or physical features in comparison to the parent compounds as well as to the respective supramolecular species. Functionalized supramolecular systems can be applied in many branches of science and life [35], including e.g. the development of new analytical [36,37,38,39,40,41] and therapeutic [42,43,44] systems, modern, intelligent (nano)materials [45,46,47,48,49,50] and molecular devices and machines [51,52,53,54,55,56,57].

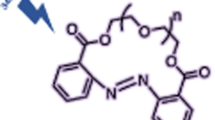

One of the most convenient and useful functionalization of macrocyclic compounds is the introduction of azo group(s): incorported in the ring or on its periphery. Azo moiety due to its ability to alter the geometry upon photochemical or thermal trans–cis isomerization can be utilized as a light triggered switch in vast variety of functional materials such as for example molecular containers, polymers, supramolecular protein channels, and sensors. As upon photoisomerization process of azo bearing molecules electromagnetic radiation is converted to mechanical work, those compounds can be used in light-driven molecular machines. Here, we present an extensive review of selected azomacrocyclic compounds with the special focus on supramolecular interactions (host–guest complex formation, self-assembly) and trans–cis isomerization of azo group.

Azobenzene and its derivatives

The properties and functions of the supramolecular systems can be controlled by external stimuli such as changing of pH, temperature, irradiation with the selected wavelength, action with electric or magnetic field. For specific goals, moieties sensitive to one or more of the above factors must be present or introduced to macrocycle structure upon its functionalization. The synthetic routes leading to macrocyclic compounds are often laborious, hence additional functionalization preferably needs relatively simple procedures. A nice example of relatively easy-to-implement functional unit with photo- and redox active properties is the azo group –\(\bar {\text{N}}{=}\bar {\text{N}}\)–, which is also pH sensitive.

Azo compounds are one of the oldest synthesized organic compounds, being produced till now on a large scale in dye industry [58]. The main synthetic approach is based on diazotization reaction discovered by Peter Griess in nineteenth century. The most common methods of azo group incorporation are schematically shown in Fig. 1. Nowadays, diverse modifications of the orginal process of diazocoupling are available; also new, synthetic procedures are proposed for preparation of azo compounds for varied purposes [59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66], including methods identified as environmentally friendly [67,68,69].

Colored azobenzenes and their more sophisticated derivatives, among others, can undergo light-driven reversible trans–cis (E⇄Z) isomerization. The reversible E⇄Z photoisomerization of azobenzene presents well-understood process widely used for construction of light-driven functional molecules for energy storage or conversion of light energy into mechanical motion, exemplified by molecular devices and machines [70]. Cis isomer of azobenzene was discovered in 1937 by Hartley [71]. Trans (E) and cis (Z) azobenzene isomers are shown in Fig. 2 that also illustrates the reversible isomerization.

Trans isomer of azobenzene is thermodynamically more stable than the cis isomer. In most cases trans→cis isomerization occurs upon irradiation with UV light (Fig. 2a). However, azobenzene derivatives undergoing reversible trans⇄cis isomerization upon visible light illumination have been also reported [72,73,74]. Such molecular switches are more applicable and safer for biological uses where harmful ultraviolet light should be avoided.

The cis⇄trans isomerization may occur by spontaneous thermal back reaction or reverse photoisomerization cycle.

The light-driven reversible E⇄Z isomerization of azobenzene is associated with substantial changes of structure, size, geometry and physical properties. Structural changes of azobenzene moiety inbuilt into a larger or more complicated compound affect also the behavior and properties of the azo-functionalized molecular systems like it is for example in photoswitches.

Dipole moment of trans isomer of azobenzene is near zero. Cis isomer of azobenzene has dipole moment 3.1 D, what determines hydrophobic/hydrophilic character of isomers. Trans (E) azobenzene is almost planar, opposite to cis (Z) isomer. In solid state in cis azobenzene the parallel phenyl rings are twisted 56° out of the plane of the azo group (Fig. 2). The different geometry of trans and cis isomers of azobenzene affects their UV–Vis spectra. The spectra (Fig. 2c) of trans and cis isomers are overlapping, but differ significantly. Band at ~ 440 nm originating from n→π* transition is more distinct for cis isomer. Strong absorption band at ~ 320 nm for trans isomer can be attributed to π→π* transition. In a spectrum of cis-azobenzene less intensive π→π* transition bands are observed at lower wavelength. The spectral differences cause different colors of both isomers, what makes the observation of isomerization process possible also in non-instrumental manner (by naked eye). Spectral properties of azobenzene derivatives are strongly dependent on the substituents in phenyl rings.

Azobenzene can also act as an important functional unit if incorporated into electrochromic materials (ECMs), which properties can be stimulated by applied potential. Such substances are outstanding candidates for materials used for production of electronic paper [75,76,77,78] or dual-stimuli-responsive systems [79, 80].

The electrochemistry of azobenzene and its derivatives in different solvents was studied exhaustively in details for both trans and cis isomers [81,82,83,84,85]. It was found that the electrochemical reduction of azobenzene is strongly dependent on conditions, such as type of the solvent, pH or reagent concentrations. However, in general it can be summarized that the reduction of azobenzene occurs in a single two electrons, two protons process with a final formation of hydrazobenzene. The simplified way of the electrochemical reduction of azobenzene is shown in Scheme 1.

The properties of self-assembled monolayers of azobenzene derivatives—also macrocyclic—on different surfaces [86,87,88,89,90,91,92] showed, that such materials are promising candidates for molecular devices for energy storage and conversion.

Cyclic and macrocyclic derivatives of azobenzene(s)

Small rings

Derivatives of cinnoline 1, e.g. benzo[c]cinnoline 2 (Scheme 2) can be considered as structural, cyclic analogs of azobenzene. These compounds are used in manufacturing of dyes, electrochromic polymers, coloured polyamide fibers and have microbial and herbicidal activities [93, 94]. Cinnolines were also studied as potential anticancer agents [95, 96]. The reduction of 2,2′-dinitrobiphenyl to 3,4-benzocinnoline (benzo[c]cinnoline) 2 (Scheme 2) was first described by Wohlfart [97] and later by other groups [98,99,100,101,102,103,104,105,106,107].

The crystal structure of benzo[c]cinnoline complex with ytterbium Yb(BC)3(thf)2 (BC = benzo[c]cinnoline) was described [108]. Fe2(BC)(CO)6 complex was examined as a candidate for a new structural and functional model for [FeFe]-hydrogenases [109, 110].

Modified with benzo[c]cinnoline or its derivatives surfaces of e.g. glassy carbon [111, 112], gold [113] or platinum [114, 115] are often used in organic, inorganic, and biochemical catalytic transformations.

Öztürk et al. [116] reported an amperometric lactate biosensor based on a carbon paste electrode modified with benzo[c]cinnoline and multiwalled carbon nanotubes. Its characteristics showed, that it can be used for determination of lactate in human serum. Incorporation of benzo[c]cinnoline moieties into poly[2-methoxy-5-(2-ethylhexyloxy)-1,4-phenylenevinylene] (MEH-PPV) indicated that p-type semiconductors based on the above polymer can be transformed into n-type materials [117].

Larger analog of cinnoline, (5,6-dihydrodibenzo[c,g][1,2]diazocine) (Fig. 3, compound 3) comprising azobenzene moiety joined by ethylene bridge at 2,2′-positions was identified as a molecular switch with interesting photochemical characteristics [118,119,120].

Adapted with permission from [119]. Copyright 2009 American Chemical Society

a 5,6-dihydrodibenzo[c,g][1,2]diazocine (3): equilibrium structures of 3Z and 3E in the electronic ground states from quantum chemical calculations at the B3LYP/def2-TZVP level of theory using the TURBOMOLE program and b colors of 3Z before irradiation and color 3E upon irradiation in n-hexane.

Interestingly, in this case cis isomer is thermodynamically more stable than trans isomer. Remarkably, both isomers of 3 have well pronounced n→π* bands in UV–Vis absorption spectra. Reversible trans to cis photoisomerization occurs with efficiency close to 100% under the illumination with visible light of 480–550 nm. The back process of rapid kinetics can be achieved at near ultraviolet at 380–400 nm.

Cyclic oligomers of azobenzene (oligoazobenzenophanes)

Oligoazobenzenophanes are compounds consisting of at least two or more azobenzene units forming macrocycles. Azobenzene moieties can be joined in para-, meta- or ortho- positions by sp3 hybridized spacers with or without heteroatoms forming relatively flexible, non-conjugated azobenzophanes (Fig. 4a). More rigid, conjugated azobenzophanes are obtained by joining azobenzene units without sp3 tether. As an example of conjugated azobenzophane the simplest cyclotrisazobenzene is shown in Fig. 4b.

Synthetic procedures leading to azobenzophanes involve also approaches typical for macrocyclization, e.g. high dilution technique or template synthesis. The formation of azo group can be the final step of ring closure or can be achieved from substrate(s) bearing functional group(s) by substitution or condensation reactions. An exhaustive review on synthetic protocols was published by Reuter and Wegner [121] that shows preparation of vast varieties of azobenzophane skeletons by cyclizations based on nucleophilic reactions, Schiff bases condensations, reductive or oxidative azocouplings, palladium catalyzed N-arylations, and electrophilic aromatic substitutions of diazonium salts.

The utility of azobenzophanes lies in reversible photoisomerization. Opposite to azobenzene for which only two possible states Z or E can be achieved by photoisomerization, macrocyclic azobenzophanes offer multiple molecular states, depending on the number of azo units. For example, for azobenzophane composed of two azobenzene fragments three states can be considered: E,E, E,Z and Z,Z (Fig. 4c) with the ratio of the isomers depending on e.g. the structure of macrocycle and photoisomerization conditions. The simplest conjugated azobenzophane cyclotrisazobenzene 4 (Fig. 4b) exits only in all-E form and has no tendency to be converted into Z form under illumination [121]. Unusual behavior of cyclotrisazobenzene was exhaustively investigated by Dreuw and Wachtveitl [122]. According to experimental and theoretical studies on ultrafast dynamics of this macrocycle the authors stated that the structural constrains prevent isomerization of azo units. The azo bonds respond elastically to the motion along the isomerization coordinates leading to complete and ultrafast dissipation of the UV excitation as heat. It was proposed that the molecules of this type can be used as UV absorbers e.g. in sunscreens.

Azobenzophanes of various structures are studied inter alia as metal cation complexing reagents. Tamaoki and co-workers [123] have obtained a series of azobenzophanes 6–8 (Fig. 5) by reductive macrocyclization of bis(3-nitrophenyl)methane under high dilution conditions. Macrocycles constructed of two, three or four azobenzene units with methylene linkers were isolated as all-E isomers. For comparative studies trans-3,3′-dimethylazobenzene 5 was prepared (Fig. 5).

The position of UV–Vis absorption maxima for compounds 6–8 and 5 registered in benzene are ring size dependent. The shift of the main band (π→π*) towards longer wavelength can be ordered as follows: 8 > 7 > 6 and reverse order for n→π* (cf. Fig. 5b) and can be associated with steric distortion of the azobenzene moieties. The position of the main absorption band of the largest compound 8 is comparable to a spectrum of open chain analog trans-3,3′-dimethylazobenzene.

The UV–Vis spectra of all-trans 6 macrocycle and all-trans isomer of acyclic dimer 5′ (Fig. 5a) in acetonitrile are compared in Fig. 6 [124]. The same Figure shows also changes upon irradiation with 313 nm wavelength light.

Reprinted from [124]. Copyright 2006 with permission from John Wiley and Sons

Left: changes in the absorption spectra of a 6 and b 5′ (Fig. 5) in acetonitrile upon irradiation at 313 nm. The insets show the n,π* band, spectral range (370–550 nm). Bold lines are the initial (solid) and final (dash) traces. Right: absorption spectra of each isomer of a 6 and b 5′ measured by use of a photodiode array detector attached to an HPLC system. Spectra are normalized at the isosbestic points (269 and 272 nm for 6 and 5′, respectively). Numbers for compounds in reproduced material correspond to following numbers of compounds in this work: 1 = 6, 2 = 5′.

Photoisomerization of macrocycles 6–8 (Fig. 5) and acyclic compound 5′ from all-trans(E) to all-cis(Z) isomers proceeds gradually via respective trans(E)/cis(Z) isomers (depending on the number of azo groups). Comparison of UV–Vis spectra of macrocycle 6 trans/trans, and its acyclic analog 5′ is shown in Fig. 6 (left). Photoisomerization studies of all-trans isomers of compounds 6–8 showed that the ratio of all-cis isomers is irradiation wavelength dependent. The increase in quantity of cis azobenzene units upon irradiation at 366 nm and decrease at 436 nm was observed for 7 and 8 in chloroform. Similar behaviour was found for photoisomerization of 6 in acetonitrile. The ratios of isomers at the photostationary state for compounds 6–8 are schematically shown in Fig. 7a–c [123].

The ratios of isomers at the photostationary state (PPS) at various wavelength irradiation for a 6 in acetonitrile, for b 7 in chloroform and c 8 in chloroform [123]

It was found that macrocyclic compounds 6–8 form complexes with alkali metal cations in methanol (determined by mass spectrometry, MS ESI). For all-trans isomers the highest peak in mass spectra was observed for cesium complexes; peak intensities for particular macrocycles can be ordered as: 6 > 7 > 8. The observed trend was disturbed upon irradiation when cis isomers also participate in complex formation. It was explained by the softer character of trans isomers. However, the clear relationship: the intensity of peaks versus ion diameter in correlation with the size of macrocyle ring was not defined. It was concluded that other factors than only host–guest geometrical complementarity affect the binding strength of metal cations by azobenzophanes 6–8 [123].

Norikane et al. [125] obtained azobenzophanes 9 and 10 (Fig. 8), having structures similar to 6–8 (Fig. 5). The modification of the macrocyclic skeleton by attaching long alkoxyl chains resulted in photoresponsive liquid crystallinity.

Azobenzophanes obtained by Norikane et al. [125]

The effect of different bulky substituents on the properties of azobenzophanes having the same macroring size was investigated by Mayor and co-workers [126]. Four m-terphenyl compounds 11–14 (Fig. 9) comprising different peripheral substituents were synthesized by multistep reactions, and different strategies, with the final step of reductive macrocyclization (LiAlH4, THF, r.t.) of the respective nitro compounds. Compounds 11–13 are symmetric opposite to derivative 14 with two different substituents at peripheral positions.

Bulky azobenzophanes synthetized by Mayor and co-workers [126]

The structures of obtained macrocycles were confirmed spectroscopically and the molecular weights of oligomers were determined by vapor pressure osmometry. UV–Vis spectra registered for macrocycles 11–14 in THF are shown in Fig. 10 (left) [126].

Reprinted from [126]. Copyright 2009 with permission from John Wiley and Sons

Left: absorption spectra of azobenzophanes 11–14: 11-solid black line, 12-dashed line, 13-solid grey line, 14-dotted line, in THF. Right: changes in absorption spectra of macrocycle 11 in THF upon irradiation at 313 nm. Inset: absorbance change versus irradiation time.

Similar shape of spectra, i.e. π→π* ~350 nm and n→π* ~450 nm was found for all compounds, although below 300 nm in UV–Vis spectra of macrocycles 11–14 the differences are more pronounced. The blue shift of absorption bands for compounds 12 and 13 can be attributed to the effect of substituents on the central phenyl rings. UV–Vis spectra of 11–14 undergo changes upon illumination (313 nm, in THF). For all compounds comparable changes were observed, what is exemplified for 11 in Fig. 10 (right). The photostationary state was reached within 8 min. Photoisomerization is observable in UV–Vis spectra by the decrease of the π→π* and the increase in the n→π* absorption bands upon irradiation over time. These changes are associated with the formation of Z isomer. Photoisomerization was monitored by 1H NMR measurements along with UV–Vis experiments (Fig. 11). By integration of the corresponding 1H NMR signals the amounts of E isomer at the photostationary state was determined to be 15%. In all cases no intermediate E,Z isomer was observed as it was in the case of similar systems studied by Tamaoki [123]. This property can be attributed to the extremely rigid structure of macrocycles 11–14. The back Z→E isomerization proceeds upon illumination or thermally. The Z isomers of the macrocycles 11–14 are stable pointing to very slow thermal back-reaction (the rate constant 1.15 × 10−6 s−1). The reversibility of the photoisomerization was investigated under illumination (450 nm). Contrary to the thermal-back process, under which macrocyles were fully converted back to E isomers, upon light stimuli ~ 15% remain in their Z form. However, this process seems to be reversible what was confirmed by experiments performed in several cycles.

Reprinted from [126]. Copyright 2009 with permission from John Wiley and Sons

a UV-Vis spectra of macrocycle 11 showing the corresponding E/Z ratio (black: thermally stable state; dark grey: 50% isomerized; light grey: photostationary state). b Corresponding 1H NMR spectra (markers indicate the peaks corresponding to the Z isomer).

The effect of the strain in azobenzophanes on the photoisomerization of azobenzene unit is well seen in cyclotriazobenzenes, a special class of azobenzenophanes, in which all azobenzene units are conjugated. The simplest compound of this class has been already shown in Fig. 4b. Wegner and co-workers [127] prepared bromo- and t-butyl derivatives of the simplest cyclotrisazobenzene 4 using o-phenylenediamine as a substrate (Scheme 3).

The general synthetic route for preparation of cyclotrisazobenzenes 4, 15 and 16 reported by Wegner and co-workers [127]

Irradiation of 4, 15 and 16 (Scheme 3) showed no isomerization under various conditions. The unfavorable change of geometry upon possible photoisomerization should result in extreme strain in the macrocyclic skeleton, thus 4, 15 and 16 exist only as all-E isomers [cf.122]

Light controlled sol–gel transition of azobenzene bismacrocycle 17 (Fig. 12) was described by Reuter and Wegner [128].

Macrocycle 17 described by Reuter and Wegner [128]

Due to significant π–π-stacking interactions macrocycle 17 forms 3D networks. Its gelation was observed in aromatic solvents, attributable to the incorporation of the solvent molecule inside the 3D π-stacking network. After UV irradiation at 365 nm the gel in o-xylene slowly liquefies as a result of dissociation of 3D network. The gel–liquid conversion of 17 upon irradiation till now is the first example of switchable 3D system which was controlled by two factors: incorporation of azobenzene units and non-covalent interaction, namely π-stacking of the azobenzene macrocyles. The proposed system can be potentially used in process where small molecules are released from the 3D network upon light stimulation.

In photoswitchable cyclic azobenzenes several factors such as ring strain and the number of azo units are crucial for photochemical properties. These features depend also on rigidity and the position of linkers connecting the azobenzene units, the symmetry of the macrocycle and the degree of bonds conjugation. If at the beginning, i.e. before the illumination, a compound with several azo units is fully symmetrical in all-E configuration, the change of one of the azo groups into Z isomer affects the geometry of the macrocycle. The more azo units in macrocyle the more configuration variations (number of isomers) and geometrical changes can be expected. Wegner and co-workers [129] investigated the effect of symmetry changes on the photostationary state upon E→Z isomerization stimulated by both light and temperature. For this purpose they used macrocyle 18 with four azo moieties shown in Fig. 13. The isomerization of 18 was monitored by UV–Vis measurements and 1H NMR spectroscopy with in situ light irradiation. 18 in THF exists in the form of all-E isomer. Upon irradiation of this solution (125 μM) at 424 nm for 73 min. a mixture of five among six possible isomers was detected: the starting all-E (21%), E,E,E,Z (49%), E,E,Z,Z (19%), E,Z,E,Z (7%), and E,Z,Z,Z (4%). Under elevated (50 °C) temperature, at photostationary state, much higher ratio of the all-E isomer (55%) was detected, but lower quantities of E,E,E,Z (32%), E,E,Z,Z (4%) and E,Z,Z,Z (1.7%) isomers and almost unchanged amount of E,Z,E,Z (6.8%) isomer. It was concluded that at photostationary state the E,E,Z,Z isomer is favored over the E,Z,E,Z isomer. Comparison of the rates of thermal back isomerization reveals that the E,Z,E,Z isomer has the highest and the E,E,Z,Z isomer the lowest thermal stability. This can be ascribed to the ring strain of the particular forms. Different states can be achieved by the arrangement of the azo groups in macroring reflecting the overall symmetry of the molecule without introduction of additional substituents or applying different wavelength of the light used for illumination.

Macrocycle 18 with four azo moieties studied by Wegner and co-workers and combination of its possible E-Z isomers [129]. (Color figure online)

Interesting, well organized system utilizing highly ordered pyrolytic graphite (HOPG) based on the photosensitive macrocycle bearing four azobenzene units 19 (4NN-M, Fig. 14) immobilized in the TCDB network was obtained and investigated by Wang and co-workers [130]. Upon UV illumination of the prepared material E,E,E,Z and E,Z,E,Z isomers are present at photostationary state. The proposed methodology was found to be useful for fabrication of nanostructures and can be valuable for production of photosensitive nanodevices.

Photoresponsive system based on macrocycle 19 (4NN-M) and TCDB on HOPG surface [130]

A ternary switch utilizing chiral macrocycle was presented by Reuter and Wegner [131]. They obtained both enantiomers R and S and racemic form of chiral bismesitylcyclotrisazobiphenyl compound 20 (Fig. 15) in about 40% yield.

Reprinted with the permission from [131]. Copyright 2011 American Chemical Society

Top: (R)-20 and (S)-20 enantiomer of bismesitylcyclotrisbiphenyl macrocyle obtained by Reuter and Wegner [131]. Bottom: CD spectra at different photostationary states at 302 nm (solid line), visible light (dashed line), and 365 nm (dotted line) (5.9 × 10−5 M), with an enlarged graph for the region 270–280 nm (inset).

Three different photostationary states were gained by irradiation of 20 with different UV (302 and 365 nm) and visible light. The photoisomerization was investigated by CD spectroscopy. A large increase in the optical rotation angle for (S)-20: [α]20D = 2128° and for (R)-20: [α]20D = − 2077° in comparison with acyclic 3,3′-diaminobismesityls comes from the helical shape of macrocyclic compounds. All E-isomer was obtained by heating samples of (S)-20 and (R)-20 at 45 °C overnight. CD spectra of two all-E enantiomers are mirror images with four different absorption maxima. Upon irradiation of all E-isomer of (S)-20 with three different wavelength the photostationary state was reached after ~ 15 min. For (S)-20 seven different isomers were detected by 1H NMR measurements: six species being different E/Z isomers (one (E,E,E), two (E,E,Z), two (E,Z,Z), and one (Z,Z,Z)). The seventh one was described as a stable conformer of the (E,E,Z)-isomer with azo bond next to the bimesityl unit in Z-form. The different ratio of these isomers at particular photostationary state is manifested in CD spectra that varied mostly in intensities, but with preserved similar overall shape. However, a difference can be observed at 275 nm, when irradiating sample with mentioned above three different wavelengths: at 302 nm—positive value, visible light—no dichroism, at 365 nm negative value what is promising for ternary switch with +, − and 0 output (Fig. 15, bottom).

Crown ethers with azobenzene moiety(-ies)

Azobenzene unit incorporated into crown ethers skeleton was first reported by Takagi and co-workers almost 40 years ago [132, 133]. Azo bearing crowns 21–24 (Fig. 16a) were obtained by Williamson reaction from dihydroxyazobenzene and alkylating agents. The synthesis of this type of compounds (21–23, Fig. 16a) was also elaborated in details by Biernat and co-workers [134,135,136,137,138,139,140]. Reductive macrocyclization of dinitropodands allowed the preparation of vast number of macrocyclic compounds showing diverse properties. By this method azoxycompounds are formed next to azocompounds. They were studied e.g. as ionophores in ion-selective membrane electrodes and chromogenic agents for metal cation complexation. At first glance—these simple compounds bring a great potential in supramolecular chemistry not only as metal cation complexing properties, but also due to photosensitivity. There are also known crown ethers with azo group located at the periphery of the molecule with brilliant example of so called “butterfly crown ethers” obtained and investigated by Shinkai et al. [141, 142]. These photo-switchable compounds were used for light-driven transport of potassium and sodium. Figure 16b shows the scheme of light-driven transport of potassium cations across organic bulk membrane with the use of photoresponsive azobis(benzo-15-crown-5) 25.

These early works on azo group bearing crown ethers inspired further development of synthetic methods, challenging functionalization, and studies (both experimental and theoretical) of properties and finally applications of macrocyclic polyethers.

Crown ethers with inherent azobenzene group(s)

Among the first synthesized crown ethers with azo unit incorporated into the macrocycle were so called “all or nothing” crown ethers exemplified by 26 (Fig. 17) obtained by Shinkai et al. [141, 143]. These photoswitchable compounds form complexes with metal cations with affinity that depends on the geometry of azo group. The cis isomer obtained by illumination binds cations, whereas in the dark the cation is released due to decreasing the cavity size being a consequence of isomerization to trans form. The spectral behavior of “all or nothing” crowns of different size of the macrocycle and their ability to form complexes with alkali metal cations was later studied theoretically using density functional theory (DFT) [144]. The results showed good agreement between experimental and computational attempts.

Computational methods were also used by Wang and co-workers [145] to study trans-azobenzene embedded N-(11-pyrenyl methyl)aza-21-crown-7 27 (Fig. 18) as a fluorogenic receptor for alkaline-earth metal cations.

Azobenzene embedded N-(11-pyrenyl methyl)aza-21-crown-7, 27 studied by DFT by Wang and co-workers [145]

According to density functional theory using B3LYP/6-31G(d) it was determined that the ether chain of trans isomer of the compound becomes almost a straight line forming a strip crown ring. Calculated structure of cis isomer shows cavity enables coordination of metal cation inside the macrocycle. The optimized structures of complexes of the host molecule and alkaline earth metal cations (Mg2+, Ca2+, Sr2+, and Ba2+) indicate that the ligand binds calcium cations the strongest due to the best match of ion radius to the cavity size. These results showed, that proposed system can act as molecular device of double function.

Tamaoki and co-workers [146] studied the effect of trans–cis isomerization of [5.5](4,4′)azobenzeno(1,5)naphthalenophane 28 (Fig. 19) on silver(I) complexation. The resolved crystal structure of 1:1 complex showed that two silver cations are complexed to form dimeric structure with azobenzenonaphthalenophane in trans form (Fig. 19 left).

Adapted with permission form [146]. Copyright 2010 American Chemical Society. (Color figure online)

Left: crystal structure of dimeric AgI complex E-28. Right: schematic illustration of photoresponsive cleavage/binding of cation-π bond. Numbering of compound in the reproduced material corresponds to number of compound in this work: 1 = 28.

1H NMR studies showed that complexation of silver cation is controlled by reversible trans–cis isomerisation of azo moiety; photoisomerization of trans to cis isomer causes the cleavage of the π–cation interaction. The opposite change was found under reverse isomeriation (Fig. 19, right).

Kirichenko and co-workers [147] described synthesis and complexing properties of four crownophanes 29–32 (Fig. 20) containing 2,7-dioxyfluorenone and 4,4′-azobiphenoxy groups joined with di-, tri-, tetra-, and pentaethylene glycol moieties. Based on NMR, UV–Vis, and X-ray data it was concluded that all macrocycles exist in solution and in solid state in trans-configuration of azobenzene unit. The trans to cis isomerization of 30 can be achieved by UV-light (365 nm) irradiation. Macrocycles 30–32 bind 4,4′-dimethylbipyridinium (paraquat) bis(hexafluorophosphate), an electron-deficient model compound. The derivatives of this compound are used in synthetic procedures leading to interpenetrating complexes (pseudorotaxanes). Complex formation of paraquat with macrocyles is based on π–π interactions between π-donor aromatic moieties of cyclophanes and π-acceptor dipyridinium core of the guest. 1H NMR and MS measurements showed the formation of 1:1 inclusion complexes of pseudorotaxane type. The stability of complexes changes in the order: 31 > > 30 > 32. The smallest macrocycle 29 does not complex the guest due to lack of complementarity between size of the guest and cavity of the host.

Crownophanes 29–32 bearing 2,7-dioxyfluorenone and 4,4′-azobiphenoxy groups synthesized and studied by Kirichenko and co-workers [147] showing binding ability of dimethylbipyridinium (paraquat) bis(hexafluorophosphate)

Described by Takagi’s and Biernat’s groups 13- and 16-membered crown ethers 22 and 23, as it was stated earlier, form complexes with metal cations. The X-ray structure of complexes of 13-membered crown with lithium bromide [148] and sodium iodide [149] were described. Metal cation complexes of larger, 16-membered crowns were also obtained. In solid state 16-membered crown forms sodium complex of 1:1 stoichiometry [150] while with potassium salt sandwich type 2:1 (crown:ion) complex [151] is created. In all cases the azo group is in trans configuration. It was also shown that the analysis of crystal structures of complexes of azobenzocrown ethers with alkali metal cations can be helpful in interpretation of the selectivity of ion-selective electrodes doped with particular macrocyle [152].

The X-ray structures of uncomplexed trans isomers of crown 22 and 23 were also investigated [153]. In the unit cells there are two independent molecules 22A and 22B or 23A and 23B (Fig. 21).

Reprinted from [153]. Copyright 2008 with permission from Elsevier. (Color figure online)

ORTEP view of a crown 22 (molecules 22A and 22B), b crown 23 (molecules 23A and 23B). In both cases the thermal ellipsoids are drawn at the 50% probability level.

The kinetics of the buildup and decay of photoinduced birefringence of crown ethers with inherent azo groups 21–24 (Fig. 16a) of different size of the macrocyle was investigated in poly(methyl methacrylate) matrix [154]. For all cases it was found that the kinetics of the buildup of the birefringence was suitably described by a sum of two exponential functions, the time constants (being function of the pumping light characteristic) and sample thickness. The dark decays were described the best by the stretched exponential function, with the characteristic parameters (time constant and stretch coefficient) being practically independent of the type of crown ether. The time constants of the signal decay were orders of magnitude shorter than the respective constants of the dark isomerization of the azo crown ethers. Thus it indicates that the process controlling the decay was a relaxation of the polymer matrix and/or a rearrangement of the flexible parts of the crowns.

The introduction of the azo group into compounds results not only in photoresponsive but also redox active properties. An example can serve 16-memebered crown 33 (Fig. 22) [155] with naphthalene joined by two oxyethylene chains. This macrocycle was used for the preparation of Langmuir–Blodgett (LB) film deposited onto solid ITO substrate. The complexation of metal cations on these electrodes can be successfully observed by cyclic voltammetry (CV). Figure 22 shows CV obtained for a 22-monolayers LB film on an ITO electrode in solutions of KCl, NaCl and LiCl (0.1 M). Bare ITO shows no redox peaks in the presence of K+, Na+ or Li+ ions. For the LB film based on crown 33 film, an electrochemical response in the presence of metal salts was observed. The change of observed signal was attributed to the specific interactions between the film and the metal ions. The peaks in voltammograms can be ascribed to the electro-reduction of the azo moiety to the hydrazo group, which consumes two electrons and two protons according to the overall reaction. The strongest effect was observed in the presence of lithium cation, showing the possibilities of its electrochemical sensing.

Reprinted from [155]. Copyright 2009 with permission from Elsevier

16-membered crown 33 and voltammograms for 22-monolayers LB films on ITO, based on this macrocyclic compound, electrode in solutions of KCl, NaCl and LiCl (0.1 M) registered with a sweeping rate of 50 mVs−1.

Similar experiments were performed for a number of macrocyclic compounds, e.g. larger 29-membered macrocyle 34 (Fig. 23), bearing two n-octyl substitutents in benzene rings and two azo groups as a part of macrocycle [156]. Langmuir–Blodgett (LB) and physical vapor deposition (PVD) films on ITO showed electrochemical response towards metal cations. Cyclovoltamperometric curves registered for LB films of 29-membered compound 34 point out that among alkali metal cations Li+, Na+ K+, potassium ion was preferentially complexed under applied conditions suggesting the best host and guest size complementarity.

29-Membered diazocrown 34 showing electrochemical response towards potassium cations [156]

The selectivity of crown ethers and other host molecules towards metal cation can be controlled also by changing the type of donor atoms. 16- and 18-membered azo- and azoxythiacrown (forming next to azo compounds) ethers 35–40 (Fig. 24, right) were obtained in satisfactory yields by Kertmen and Szczygelska-Tao [157] using reductive macrocyclization procedure. Thiacrowns were tested as ionophores in ion-selective, graphite screen printed electrodes. Opposite to their oxygen analogs, sulfur containing compounds preferentially supposed to form complexes with softer metal cations. All electrodes doped both with azo- and azoxythiacrowns 35–40 (Fig. 24) showed high sensitivity towards heavy metal cations. The effect of softer sulfur donor atom in the skeleton of macrocycles on the response of ISE with membrane doped with 35–40 can be visualized by comparison of the order of potentiometric selectivity of thia-crown and its oxaanalog [137], shown in Fig. 24 (right, in a frame).

Left: Thiaazo- (35–37) and thiaazoxy (38–40) crown ethers obtained by Kertmen and Szczygelska-Tao. Right: comparison of the trend of potentiometric selectivity coefficients of electrodes with crown 36 and its oxygen analog shown is in a frame [157]

Potassium selectivity of electrodes based on derivatives of 16-membered crown ether 23 was well-proved over years of working with ISEs. 13-membered azobenzocrowns, derivatives of compound 22 (Fig. 16a) are sodium ionophores [134, 136,137,138, 158,159,160]. To improve the characteristic of the sodium and potassium sensors, important for clinical analyses, new derivatives of both 13- and 16-membered crowns were prepared and at the same time new technical solutions, including miniaturization of the sensors, were applied. Recently, a series of bis-(azobenzocrown)s (compounds 41–48, Scheme 4) based on the skeleton of parent 13- and 16-membered crowns 22 and 23 (Fig. 16a) linked by α,ω-dioxaalkane chains between two macrocycles have been obtained [162]. Bis-crowns were synthesized from the respective hydroxyazobenzocrowns obtained in reaction analogous to Wallach rearrangement elaborated by Luboch [161].

Synthetic route for preparation of bis-(azobenzocrown)s 41–48 from hydroxyazobenzocrowns as substrates [162]

The unique structure of intermolecular of 2:2 stoichiometry sandwich-type complex of bis-(azobenzocrown) 41 with sodium iodide was obtained [162]. It is presented in Fig. 25.

Reprinted from [162]. Copyright 2012 with permission from Elsevier

Two projections of macrocyclic cation [Na2(trans-41)2]2+ in 41-NaI complex with a partial labeling scheme.

Bis-(azobenzocrown)s 41–48 were used as ionophores both in classic and miniature, all-solid state, screen-printed, graphite ion-selective electrodes. New sodium and potassium sensors feature by short response times, stable potential and high selectivity, in particular high K/Na selectivity.

Bis-(azobenzocrown)s 41–48 form complexes with metal cations also in acetonitrile. The increase of stability constant values comparing analogous monocrown bearing alkoxy substituent proves beneficial effect of the presence of two binding sites in one molecule.

Another example of biscrowns are diester derivatives of dodecylmethylmalonic acid joining two 13-membered azobenzocrown moieties obtained in Luboch group [163] (compounds 49 and 50, Scheme 5). Biscrowns were obtained using bromoalkoxy derivatives of azobenzocrowns [164] and potassium salt of dodecylmethylmalonic acid in ~ 40% yield. For comparative studies monoester derivative 51 was synthesized.

Synthesis of bis-(azobenzocrown)s 49 and 50, diesters of dodecylmethylmalonic acid and monoazobenzocrown 51 [163]

For biscrowns 49 and 50 three isomers trans–trans, trans–cis and cis–cis can be considered. From 1H NMR spectra registered in d-acetone it was found that in solutions of 49 and 50 trans–trans and trans–cis isomers dominate representing altogether ~ 90% of the total amount of compounds. The presence of cis–cis isomer of 49 was observed upon irradiation with UV light. For monoester derivative 51 the ratio of trans to cis isomer was evaluated as 6:4. Trans–trans and trans–cis isomers of 49 and especially of 50, differ significantly in TLC properties. This can be associated with different complexation properties of both isomers [166]. Trans isomers of azobenzocrowns show higher affinity towards metal cations than cis forms. Thus trans–trans isomer is probable able to form intramolecular sandwich type complexes (Fig. 26) with metal cations whereas for trans–cis isomer rather intermolecular complexes are expected. This hypothesis finds confirmation in previously published works of the above authors and in articles published by other groups [149, 166, 167].

Reprinted without changes from [163]. Copyright 2016 with permission from Springer Publishing Company (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

Proposed organization of biscrown 49 sodium cation complex.

Formation of sodium complex by trans–trans isomer of 49 was confirmed also by 1H NMR measurements. Stability constant value of (1:1) complex of 49 in acetone was estimated as logK ~ 3.0 from UV–Vis titrations.

Bis-crowns 49 and 50 based on 13-membered rings, were tested as sodium ionophores in classic and miniature, solid contact: screen-printed and particularly glassy carbon membrane ion-selective electrodes. Plasticizers 2-nitrophenyl octyl ether (o-NPOE) and more lipophilic di(2-ethylhexyl) sebacate (DOS) can be successfully used for bis(azobenzocrown) containing membranes. It was proved that possible isomerization under usual conditions does not significantly affect the characteristics of the prepared electrodes. The influence of UV irradiation on the properties of glassy carbon electrode with ionophore 49 is shown in Fig. 27. After exposition to UV light (1 h, 365 nm), the electrode regains its properties practically after 2 h conditioning in NaCl solution.

a Selectivity coefficients (SSM, 0.1M) and b potentiometric response characteristics: LDL [loga] and slope [mV/dec] for glassy carbon sodium selective electrodes based on 49 as ionophore. UV-electrode upon irradiation with UV light (9W) [163]. (Color figure online)

Electrodes with the tested biscrowns 49 and 50 were found to have better selectivity coefficients KNa/K than the electrodes with the monocrown 51. The best selectivity coefficient Na/K was achieved for the screen printed graphite electrode with the addition of carbon nanotubes into the membrane (50 as the ionophore, logKNa,K = − 2.6). No significant differences were also observed between the selectivities of the classic and solid contact electrodes. In the last case lower detection limits (LDL) may be obtained. The membrane doped with carbon nanotubes deposited onto graphite screen-printed electrodes results in the better potential stability, detection limit and selectivity of biscrown-based electrodes. The electro-conductive material was introduced directly into the membrane in a manner analogous to that proposed by Ivaska and co-workers [168]. For glassy carbon electrodes to improve the conductivity, between the membrane and glassy carbon the conductive PEDOT/PSS polymer blend was introduced by electropolymerization. Such electrodes have better (lower) LDL than plain glassy carbon electrode. Electrodes with ionophores 49 and 50 characterize with response times not longer than 10 s, illustrated in Fig. 28 for membrane electrode doped with 49.

Reprinted without changes from [163]. Copyright 2016 with permission from Springer Publishing Company (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/). (Color figure online)

Response time of glassy carbon electrode with membrane with ionophore 49 (o-NPOE as plasticizer) A 0.9 mL of NaCl solution (0.1M) was injected to 100 mL of NaCl solution (10−4 M), B 0.9 mL of NaCl solution (1M) was injected to 100 mL of NaCl solution (10−3 M).

Electrodes based on 49–51 characterize by stable potential in a wide range of pH, depending on the type of the used plasticizer, e.g. electrodes with compound 49 and DOS show stable potential in the pH range 2–10 (0.1M NaCl). Proposed sodium sensor (based on 50) fulfills requirements for electrodes used in clinical analysis [169]. The response of electrodes based on 50 for sodium in the presence of interfering metal cations corresponding to their blood plasma levels are shown in Fig. 29.

Reprinted without changes from [163]. Copyright 2016 with permission from Springer Publishing Company (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

Response curves for Na+ obtained with ISEs based on ionophre 50 a graphite screen-printed electrode b glassy carbon electrode. Curve A indicates the response for Na+ without and curve B Na+ in the presence of interfering ions (4.2 mM K+, 1.1 mM Ca2+, 0.6 mM Mg2+).

The electrodes were tested for sodium in blood plasma giving consistent results with independent measurements carried out in clinical analytical laboratory.

Crown ethers with peripheral azo group

The interactions between photoswitchable azobis-(benzo-18-crown-6) and alkaline earth metal cations were studied by DFT and reactive molecular dynamics (reactive MD) by Pang et al. [170]. Optimized structures of complexes revealed that in the case of Ba2+ complex the distance between two cations is the largest among tested complexes in their trans form, and the shortest among cis complexes. Macrocycles become face-to-face when complexing Ba2+ ions. Small energy difference between Ba2+ complex in its trans and cis form indicates facile cis to trans thermal conversion. Calculation the Ba2+ complex allows to conclude that it is a suitable candidate for photocontrolled catalysis.

To mimick the structure and function of biological ion channels the light-regulated transmembrane system was proposed by using tris(macrocycle) system based on diaza-18-crown-6 joined by azobenzene photoswitchable moieties 52 (hydraphile 1, Fig. 30) [171]. The liposome-based ion transport assays revealed that compound 52 displays an efficient transmembrane activity with Ymax around 0.7 at 40 μmol/L of 52 in DMSO. Due to the presence of azobenzene moieties the potassium ion transport by the molecule across bilayer membranes can be regulated by applaying of external source of light. The photoisomerization of azo groups induces changes of transmembrane length of the ion channel and this way regulating the efficiency of the ion transport.

Reprinted from [171]. Copyright 2015 with permission from Elsevier

Tris(macrocyle), amphiphilic azobenzene moiety bearing compound 52 - hydraphile 1 (top) and schematic presentation of transmembrane ion transport in photoswitchable system based on hydraphile.

In many chemical and photochemical processes donor–acceptor complexes (D-A complexes) play an important role. Such systems are also investigated as organic conductors and photoconductors that find applications in nonlinear optics. D–A complexes of a series of bis(crown)stilbenes, and also of bis(crown)azobenzene with salts of alkylammonium viologen derivatives were studied in solution and in a solid state by Gromov and co-workers [172]. X-ray structure of complex of bis(18-crown-6)azobenzene 53 (Fig. 31) with viologen derivative 54 showed that the central parts of donor and acceptor molecules feature planar geometry. The proposed systems can be used for the design of optical sensors and molecular devices.

Structure of bimolecular complex of bis(18-crown-6)azobenzene 53 with viologen derivative 54. Reproduced from [172]. Copyright 2008 with permission from Springer Publishing Company

Colorimetric and spectrophotometric ion receptors

Molecular recognition can be utilized in many branches of science and technique if the information about host–guest interaction could be converted into analytically useful signal, e.g. optical or electrochemical. Optical signaling in the visible range of the electromagnetic spectrum draws special attention because it enables non-instrumental sensing of various chemical species such as ions or neutral molecules, e.g. for monitoring of ions of biological or/and environmental importance. The receptor molecule besides binding site should be equipped with additional signaling unit, a functional group joined via linker or chromophoric/fluorophoric moiety forming an integral part of the molecule. Schematically, the idea of chromo- and fluorogenic molecular receptors is shown in Scheme 6. The mechanism of sensing depends on the nature of both the host and the guest. The binding mode, selectivity and sensitivity can be also influenced or controlled by the effect of the solvent and/or receptor immobilization on solid surfaces of various properties.

Inter alia functionalized macrocyclic compounds bearing azo moiety belong to this relatively popular group of sensing materials.

In the case of para- and ortho- hydroxyderivatives of azocompounds the color signaling mechanism may be associated with the change in the tautomeric equilibrium upon complexation. This is well illustrated by tautomeric switch based on functionalized azacrown ether 55 (Fig. 32) synthesized and investigated by Antonov and co-workers [173]. Uncomplexed ligand in acetonitrile exists in azophenol form stabilized by intramolecular hydrogen bond between phenolic OH group and nitrogen atom of crown ether residue. In the presence of alkali and alkaline earth metal cations—the color of the solution turns from yellow to orange–red, what is a result of bathochromic and hyperchromic effects in UV–Vis spectra. The complex formation is connected with the shift of the tautomeric equilibrium towards ketone (quinone-hydrazone) form. Metal cations are complexed by ether oxygen donor atoms and by carbonyl oxygen atom of ketone form.

The mechanism of color change of azacrown ether modified with 4-(phenyldiazenyl)naphthalen-1-ol 55 synthesized by Antonov et al. exemplified by sodium complexation [173]

Lithium and sodium cations form complexes of 1:1 stoichiometry with azacrown 55 (Fig. 33). For magnesium and calcium initially 1:1 complex is formed. Under an excess of a metal salt 2:2 complex dominates. Direct 2:2 complex formation was found for barium perchlorate. Absorption spectra of azacrown registered in the presence of metal perchlorates are shown in Fig. 33a. In Fig. 33b the values of the stability constants of 1:1 and 2:2 metal complexes with discussed azacrown 55 are presented.

a Normalized absorption spectra of azacrown 55 (─) in CH3CN and its final complexes with alkali and alkaline earth metal ions. Reprinted from [173]. Copyright 2010 with permission from Elsevier. b the values of the stability constants of azacrown with metal cations and the position of the absorption maxima for the respective complexes

Aza-15-crown-5 56 (Fig. 34) skeleton is a hopeful building block for colorimetric sensors. Lincoln and Sumby [174] used this macrocyle to synthesize N-[4-(phenyldiazo)benzenesulfonyl]-aza-15-crown-5 57 (Fig. 34). This chromogenic compound was obtained in 55% yield by treating commercially available 4-phenyldiazobenzenesulfonyl chloride with aza-15-crown-5 in DMF in the presence of triethylamine. The synthesized lariat ether was studied as metal cation reagent in ethanol–water (75:25 v/v, pH 6.66) mixture. The stability constant values of 1:1 complexes of sodium and potassium cations with 57 are higher than for the parent aza-15-crown-5 56 (Fig. 34) and its derivatives [175,176,177,178]. The solved X-ray structure of [Na(57)(H2O)]2(ClO4)2 complex showed that it is a dimer with the sulfonamide oxygen atom engaged in cation complexation. This indicates the cooperation of sulfonamide side arm and crown ether moiety in ion binding and explains the higher values of the stability constant compared with data for unsubstituted aza-15-crown-5.

The selectivity of metal cation binding can be controlled by using macrocycles with softer, sulfur donor atoms. Lee and Lee [179] synthesized, under high dilution conditions, macrocyclic derivatives incorporating aromatic moiety, i.e. benzene 59 or pyridine 60 (Scheme 7) within the macroring. Chromogenic character of macrocycles was achieved by extending the structure by diazocoupling of the obtained in the first step N-phenylated macrocyles 58 with p-diazonium salt.

Synthetic route for preparation chromogenic macrocyles 59 and 60 [179]

Both compounds 59 and 60 selectively bind mercury(II) in acetonitrile forming 1:1 complexes. Complexation of Hg2+ causes hipsochromic shift of absorption bands from 480 to 339 and 378 nm for 59 and 60, respectively. Among other investigated metals only copper(II) cations cause bathochromic shift of absorption band of 59, whereas spectral behavior of 60 remains intact. Color and spectral changes of 59 and 60 in acetonitrile solutions in the presence of metal salts are shown in Fig. 35. The crystal structure of 60 complex with mercury(II) ion showed metal cation located inside the macrocycle cavity. The difference in selectivity towards mercury ions versus other metal cations was explained by the engagement of the pyridine nitrogen atom in complex formation in case of 60.

Reprinted with permission from [179]. Copyright 2009 American Chemical Society

UV–Vis spectra of a 59 and b 60—(40 μM) in the presence of metal perchlorates (5.0 equiv) in acetonitrile. Numbers of compounds in reproduced material correspond to following numbers of compounds in this work: L1 = 59; L2 = 60.

Spectral and color changes in the presence of Hg2+ were found to be anion dependent (Fig. 36). Addition of perchlorates or nitrates to the acetonitrile solution of mercury(II) complexes of 59 and 60 causes spectral and color changes, which can be attributed to the ability of mercury to coordinate these anions. The obtained results indicate that proposed macrocycles can be used not only as mercury, but also as anion sensing molecules.

Reprinted with permission from [179]. Copyright 2009 American Chemical Society

UV–Vis spectra of a 59 and b 60 - (40 μM) in the presence of Hg2+ (5.0 equiv) upon addition of anion salts in acetonitrile. Numbers of compounds in reproduced material correspond to following numbers of compounds in this work: L1 = 59; L2 = 60.

Spectral and color changes caused by complexation of heavy metal cations were also found for macrocyle 61 bearing as chromogenic substituent p-nitroazobenzene [180] that was obtained in multistep reaction shown in Scheme 8.

Synthesis of chromogenic macrocyle 61 [180]

Red acetonitrile solution of 61 changes color to yellow upon addition of metal salt, which is a result of metal cation induced hypsochromic shift of absorption band. The largest spectral and color changes among investigated metal cations causes copper(II) (Δλmax = 174 nm). The spectral and color changes of 61 in the presence of metal nitrates are shown in Fig. 37.

Reprinted with permission from [180]. Copyright 2009 American Chemical Society

Changes in the UV–Vis spectrum of 61 on addition of metal nitrates in acetonitrile (ligand concentration, 5.0 × 10−5 M; and added metal ion, 3.0 equiv). Number of compound in reproduced material corresponds to following number of compound in this work: L2 = 61.

Compound 61 forms two types of solid state complexes, which differ in color: [Cu(61)NO3]NO3·CH2Cl2, a pale-yellow and dark red [{Cu(61)}2(μOH)2](ClO4)2·2CH2Cl2·2H2O. The effect of counter ion on spectral changes upon copper(II) complexation was investigated using chloride, nitrate, perchlorate, acetate, and sulfate salts. A blue shift was observed and the influence of anion can be set in the following order: NO3−, ClO4− > Cl−, AcO− > SO42−, which is in accordance with the Hofmeister series of relative anion lipophilicities.

Colored systems can be also used for preparation of sensing materials by immobilization of the respective receptor(s) on a chosen solid surface. For example, macrocycle 62 (Scheme 9) bearing azo unit, was immobilized on a silica nanotubes (SNT) using sol–gel method [181]. The described system (SNT-62) was presented as a heterogenous “naked-eye” and spectrophotometric metal cation sensor.

Schematically: modification of silica nanotubes with chromogenic macrocylic derivative 62 (SNT-62) [181]

Inorganic–organic nanomaterial (SNT-62) shows in water selective response by color change from yellow to violet towards Hg2+ among all other investigated metal cations: Ag+, Co2+, Cd2+, Pb2+, Zn2+, Fe3+, Cu2+. The color of suspensions also changes in the presence of nitrate and perchlorate anions from yellow to pink and violet, respectively. The addition of Cl−, Br−, I−, SCN−, or SO42− salts does not cause color change. It was also shown that modified silica nanotubes can act not only as colorimetric sensor for mercury(II) cation, but also for preparation of stationary phases for ion chromatography. The use of suspensions can be sometimes troublesome, thus a portable chemosensor kit was prepared by modification of the glass surface with SNT-62. The material also in this form exhibits selective response towards Hg2+ with color change from yellow to violet upon dipping in solution of mercury(II) salt. Color changes of the water suspensions of SNT-62 upon addition of mercury(II) nitrate at different concentrations are shown in Fig. 38 (left). The color change of the glass sensor modified with SNT-62 upon immersion into mercury(II) and for comparison copper(II) aqueous solutions is shown in Fig. 38 (right).

Reprinted from [181]. Copyright 2007 with permission from John Wiley and Sons

Left: pictures of the suspensions: a SNT-62, b SNT-62 + 0.01 mM Hg(NO3)2, c STN-62 + 1.0 mM Hg(NO3)2. Right color changes of glass plates coated with SNT-62: a before immersion and after immersion in b Hg2+ (0.01 mM) and c Cu2+ (0.01 mM) solution in water.

Environmentally hazardous mercury(II) sensing based on dithiaazadioxo crown ether system with peripheral azo unit was described by Ha and co-workers [182]. Compounds 63 and 64 (Fig. 39) were investigated as Hg2+ receptors in solvents of diverse polarity (acetonitrile, its mixture with water and in chloroform). It was found that host–guest interaction strongly depends on the solvent nature. According to 1H NMR and spectrophotometric measurments it was stated that both ligands in acetonitrile form 1:1 complexes, if Hg2+ is coordinated inside the macrocyclic cavity (Fig. 39). As a consequence of molecular recognition solutions of both ligands undergo discoloration in the presence of Hg2+ ions. In less polar chloroform, different mechanism of ligand-ion interaction was proposed. Two molecules of 63 probably bind one mercury(II) cation forming sandwich complex. This is manifested by color change from yellow to pink. In the case of macrocycle 64 in chloroform complexes of 2:2 stoichiometry are formed.

Proposed mechanism of mercury(II) complexation by macrocycles 63 and 64 depending on the solvent type [182]

Ha and Jeon continued the work on selective mercury(II) sensing using compound 63 (Fig. 39) [183]. The colored macrocycle was applied for recognition of Hg2+ ions in aqueous solution. The effect of two surfactants cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB) and sodium dodecylsulfate (SDS) on spectral and color behavior of 63 was investigated. In the presence of CTAB the solution of 63 is yellow, while pink color is observed in the presence of SDS (Fig. 40). In the presence of Hg2+ the pink solution of 63-SDS system becomes colorless enabling naked-eye ion recognition with detection limit 1.6 μM. The 63-SDS based system was also used for preparation of the mercury sensitive cellulose test strips.

Reprinted from [183] Copyright 2015 with permission from John Wiley and Sons. (Color figure online)

Color and spectral changes of 63 in various concentrations of a CTAB and b SDS.

Functionalized azobenzocrowns (azo moiety as a part of the macrocycle)

This chapter highlights the preparation and properties of azobenzocrowns, of different size of the macrocycle, equipped with additional functional groups in benzene rings: hydroxyl, amino, and dimethylamino, as well as pull–push type azobenzocrowns with nitro and dimethylamino groups.

13-, 16- and 19-membered crowns bearing electron donating (dimethylamino) 65–67 or two different electron donating/accepting groups (dimethylamino and nitro) 68–70 in the azobenzene fragment (Scheme 10) were obtained with the yields up to 55% [159].

Synthesis of functionalized azobenzocrowns 65–70 [159]

Compounds 65–70 exist only in E form, both in the solid state and in solution. In Fig. 41 X-ray structure of 70·2H2O is presented, showing the E geometry of the azo unit with aromatic moieties in the trans-positions and proved the existence of a molecular diaqua-complex [159].

Reprinted from [159]. Copyright 2005 with permission from Elsevier

Molecular structure of 70·2H2O with atom labeling scheme; ellipsoids are drawn at 50% probability level.

The absorption spectra of 65–70, opposite to the parent azobenzocrowns 22–24 (Fig. 16a) have sharp and well pronounced maxima (Fig. 42).

Comparison of absorption spectra of azobenzocrowns: parent—22 (solid line), and functionalized with: dimethylamino—65 (dashed line) and dimethylamino- and nitro—68 (dotted line); (c = 7.0 × 10−5 M) in acetonitrile. Spectra reproduced from [159]. Copyright 2005 with permission from Elsevier

The UV–Vis studies of alkali and alkaline metal cation complexation by compounds 65–70 showed magnesium selectivity of 19-membered azobenzocrown 67 in acetonitrile. Only in this case the complexation is characterized by significant spectral shift (Fig. 43) and by distinctive color change from orange to pink.

Reprinted from [159]. Copyright 2005 with permission from Elsevier

The comparison of absorption spectra of 67 (solid line, c = 5.7 × 10−5 M) and limiting spectra in the presence of: potassium (dashed line, c = 2.6 × 10−3 M), strontium (dotted line, c = 4.4 × 10−5 M) and magnesium (solid line with maximum at ~ 520 nm, c = 1.9 × 10−3 M) perchlorates in acetonitrile.

Another set of synthesized and investigated functionalized azobenzocrowns consists of derivatives with a hydroxyl substituent. Azobenzocrowns with hydroxyl group located in one of the benzene rings, in the para position to the azo group, have been synthesized prior to 2002 [158] and are also a part of current works carried in Luboch’s group.

A simple method for the synthesis of 13- and 16-membered azobenzocrown ethers, derivatives 4-hexylresorcinol 71–73 with two peripheral groups, i.e. nitro and hydroxyl groups at two opposite sides of the conjugated chromophoric system has been described by Luboch et al. (Scheme 11) [160].

The synthesis of azobenzocrown ethers with peripheral hydroxyl group 71–73—derivatives of 4-hexylresorcinol [160]

Typical for 13-membered azobenzocrowns, including compounds 71 and 72 is selective binding of lithium cations. The most significant, among all investigated so far compounds of this type, is the spectral shift of 95 nm and color change from yellow to pink found for 72 (Fig. 44) in basic acetonitrile (Et3N) solution. Crown 73 is more lithium sensitive, but less selective, versus sodium and potassium (Fig. 44) giving the color change. The chromoionophoric behavior of the compounds potentially allows their application, under selected conditions, for construction of optical sensors.

Reprinted from [160]. Copyright 2009 with permission from Elsevier

Color changes of azobenzocrowns solutions with peripheral hydroxyl group 72 (n = 1) and 73 (n = 2) in the presence of metal perchlorates in acetonitrile.

As shown in Scheme 12 the hydroxyazobenzocrowns undergo tautomeric equilibrium to quinone-hydrazones. The tautomeric equilibrium of hydroxyazobenzocrowns is affected by the size of the macrocycle. The larger the cavity size the lower the tendency to occur in the quinone-hydrazone form. This can be explained by weaker hydrogen bonds in macrocycles of larger cavity. 13-membered macrocyclic p-hydroxyazobenzene derivative—compound 74 (Scheme 11), in the solid state and in solvents of different polarity (chloroform, acetonitrile, acetone or methanol) exists in the quinone-hydrazone form. The azophenol form was observed (~ 30%) in DMSO.

Tautomeric equilibrium for hydroxyazobenzocrown ethers 74–76 showing hydrogen bond inside the cavity of quinone-hydrazone form [158]

16-Membered crown 75 in chloroform and in acetonitrile exists, like 74, in the quinone-hydrazone form, but in DMSO only the azophenol form was found. Compound 76 of 19-membered ring entirely exists in the azophenol form in DMSO and chloroform. In acetonitrile no less than 75% of this form was detected [159], but in acetone both forms exist in comparable amounts.

p-Hydroxyazobenzocrown ethers can be obtained from O-protected podands by reduction [158] or directly from dihydroxyazocompounds as shown for stericaly hindered crowns 71–73 [160]. The reaction analogous to the Wallach rearrangement was proposed as a method for preparation of p-hydroxyazobenzocrowns using azoxybenzocrowns as substrates [161]. However, the reaction carried out in the mixture of concentrated sulfuric acid and ethanol suffers from the formation of side products and large amounts of used reagents [162]. Exhaustive synthetic research on the applicability of Wallach rearrangement allowed to conclude that the decrease of the side-products formation, lower amounts of reagents and finally, the most importantly, significant yield increase is obtained by carrying out the Wallach rearrangement in a mixture of concentrated sulfuric acid and dimethylformamide [165]. Under elaborated reaction and isolation conditions a series of hydroxyazobenzocrowns 74, 75 and 77–83 were successfully obtained (Scheme 13).

Rearrangement of azoxybenzocrowns in the presence of concentrated sulfuric acid and DMF [165]

In contrast to the Wallach rearrangement conducted under strongly acidic conditions where mostly p-hydroxyazo compounds are formed, the photochemical rearrangement leads also to ortho-hydroxyazo compounds 84, 85 (Scheme 14) [162]. Under fixed conditions the ratio of para to ortho hydroxyazobenzocrown isomers was dependent on the solvent. In toluene o-substituted compounds were dominating, p-substituted crowns were the main product in ethanol, whereas in DMF a mixture of comparable amounts of both isomers were obtained.

Azoxybenzocrowns: trans–cis photoisomerisation and photochemical rearrangement leading to ortho- (84, 85) and para-hydroxyazobenzocrowns (74, 75) [165]

o-Hydroxyazobenzocrowns opposite to p-substituted analogs, exist mainly in azophenol form.

The spectral properties of o-hydroxyazobenzocrowns 84 and 85 were compared with 74 and 75, and unsubstituted crowns 22 and 23 (Fig. 16a) [165]. Their normalized UV–Vis spectra (acetonitrile) (solid lines) and the corresponding protonated forms (dashed lines) are shown in Fig. 45a, b. Protonation constants in acetonitrile solutions are compared in Fig. 45 (right). The protonation constants can be ordered: p-hydroxyazobenzocrowns > o-hydroxyazobenzocrowns > unsubstituted azobenzocrowns ~ acyclic analog of azobenzocrowns 86.

Reprinted from [165]. Copyright 2013 with permission from Elsevier. (Color figure online)

Left: comparison of normalized UV–Vis spectra of (a) 13-membered (b) 16-membered azobenzocrowns (solid) and their protonated forms (dashed lines) Right: proton binding constants for 22, 84, 74 and 23, 85, 75 azobenzocrowns and for acyclic analog 86 in acetonitrile. Number of compounds in reproduced material correspond to following numbers of compounds in this work: 10 = 74; 10a = 22; 23 = 84; 11 = 75; 11a = 23; 24 = 85; 22 = 86.

p-Hydroxyazobenzocrowns were used as substrates in the synthesis of bisazobenzocrowns (Scheme 15) of different lipophilicity, where two macrocyclic residues are joined via dioxymethylene group. Biscrowns (87–93) were obtained in yields up to 72%.

Synthesis of bisazobenzocrowns 87–93 with dioxymethylene spacer [165]

Bisazobenzocrowns were used as ionophores in classic and miniature (screen-printed) ion-selective electrodes. A selectivity coefficient logKNa,K = − 2.5 (SSM, 10−1 M) for electrode with crown 87 as ionophore was one of the best result obtained for the whole group of the electrodes based on the 13-membered azobenzocrowns. Within the investigated 16-membered bisazocrowns the best potassium over sodium selectivity coefficient for potassium electrodes was logKK,Na = − 3.5 (SSM, 10−1 M) found for compound 88.

13- and 16-Membered azobenzocrowns (Scheme 16) with aromatic amino (94, 95), amide (96, 97), ether–ester (98–103) or ether–amide (104–107) residue in para position to an azo moiety were synthesized and investigated [184].

Synthesis of a amino (94, 95), b amide (96, 97), c ether–ester (98–103) or ether–amide (104–107) derivatives of azobenzocrowns [184]

The studies of tautomeric equilibrium of aminocrowns 94 and 95 showed that in majority of solvents, similarly to open chain aminoazocompounds [185] they exist in aminoazoform (Scheme 17). It is opposite to discussed above hydroxyazobenzocrowns for which tautomeric equilibrium was found to be more solvent dependent [158, 159, 186].

Comparison of tautomerism of 13-membered hydroxy- and aminoazobenzocrowns [184]

The protonation of aminoazobenzocrowns shifts the tautomeric equilibrium towards protonated iminohydrazone form.

13-Membered crown 94, as expected, in acetonitrile preferentially complexes lithium ions. Stability constant of this 1:1 complex is logK = 4.0. This value is comparable with the value for unsubstituted 22 (logK = 4.1), but it is higher than for the corresponding 13-membered hydroxyazobenzocrown 74. The stability constant obtained for magnesium complex, logK = 6.43, is the highest value for magnesium complex among all studied so far azobenzocrowns. Changes in the absorption spectra upon spectrophotometric titration of a solution of 94 with lithium and magnesium perchlorates in acetonitrile are illustrated in Fig. 46a, c. Fig. 46b shows limiting spectra for 94 upon titration with alkaline earth metal perchlorates.

Reprinted from [184]. Copyright 2013 with permission from Elsevier. (Color figure online)

Changes in absorption spectra upon titration of solution of 94 (c = 3.27 × 10−5 M) with perchlorates: a lithium; c magnesium; b the limiting spectra obtained during spectrophotometric titration of solution of 94 with alkaline earth metal perchlorates in acetonitrile.

16-Membered aminoazobenzocrown 95 forms 1:1 complexes with alkali and alkaline earth metal cations. In all cases, with exception for potassium, the values of the corresponding stability constants are higher than for parent azobenzocrown 23, which are in turn higher than for complexes of hydroxyazobenzocrown 75. The introduction of electron-donor amino group into the benzene ring in para position to azo moiety enhanced binding properties of azobenzocrowns.

Lithium binding was investigated for a series of 13-membered azobenzocrown with oxyalkylcarbonester moiety as side chain 98, 100, 102 (Scheme 16) and was compared with properties of 22 and its alkoxy derivative 108 (Fig. 47).

Alkoxy azobenzocrown 108 [184]

The general trend of spectral changes upon lithium complexation for oxyalkylcarbonester derivatives is similar as for 108. The length of aliphatic acid chain has some effect on the binding strength of the lithium ions, however it cannot be the complexation of the same type as for lariat type crowns. The side chain seems to be too short to participate in complex formation. This is to some extent confirmed by the crystal structure of sodium iodide complex 101 (Fig. 48).

Reprinted from [184]. Copyright 2013 with permission from Elsevier

The crystal structure of sodium iodide complex of compound 101.

Vast majority of azo compounds, with few exceptions [105, 187,188,189,190] show no fluorescence. Protonated azobenzocrowns exhibit orange-red fluorescence. The position of emission band, and the value of the Stoke’s shift is dependent on the presence and nature of the substituent in the para position to the azo group [184]. Comparison of normalized absorption and the corresponding emission spectra for protonated forms of 13-membered azobenzocrowns 22, 94 and 96 are shown in the Fig. 49a, b.

Reprinted from [184]. Copyright 2013 with permission from Elsevier. (Color figure online)

Normalized a UV and b fluorescence spectra of protonated 13-membered azobenzocrowns 22 (λex = 487 nm, λem = 608 nm), 94 (λex = 482 nm, λem = 568 nm) and 96 (λex = 490 nm, λem = 576 nm) in acetonitrile. Numbers of compounds in reproduced material correspond to following numbers of compounds in this work: A = 22; 1 = 94; 3 = 96.

Changes in the UV–Vis and emission spectra of compound 96 solution upon titration with solution of p-toluenesulfonic acid in acetonitrile are shown in Fig. 50a, b. Photos show a color change and red fluorescence of 96 caused by protonation.

Reprinted from [184]. Copyright 2013 with permission from Elsevier. (Color figure online)

a Changes in UV–Vis and c in emission spectra of 96 (λex = 510 nm, λem = 598 nm) (3.73 × 10−5 M) upon titration its solution with p-toluenesulfonic acid solution (TosOH); b color change and d red fluorescence of 96 in the presence of two-fold excess of TosOH in acetonitrile.

Selected functionalized azobenzocrowns (Scheme 16) were tested as ionophores in ion-selective membrane electrodes. Ether-ester 100–103 and ether-amide 104–107, similarly to described earlier alkyl and dialkyl derivatives [136, 137, 158] are good ionophores in membrane electrodes. The mechanism of ion selectivity can be explained by formation of “sandwich” type complexes with the main ions [149, 151].

The 1H NMR studies of tautomeric equilibrium of hydroxyazobenzocrowns with phenyl substituents in benzene rings (Fig. 51) showed that 13-membered crown 109 in acetonitrile exists in quinone-hydrazone form [191]. 10% of azophenol form was detected in DMSO. For 16-membered crown 110 the presence of quinone-hydrazone form was stated in acetone and chloroform [191] and also in DMSO (50%).

Hydroxyazobenzocrowns 109 and 110 with phenyl substituents in benzene rings [191]

For 13-membered hydroxyazobenzocrown 109 spectral response with spectral shift ~ 40 nm (Fig. 52a) and color change from yellow to orange (Fig. 52, top) caused by the presence of lithium salt was observed only in basic solution (Et3N) of acetonitrile. This corresponds to lithium complex formation by ionized hydrazone form of 109. Lithium response is observed also in the presence of the excess of sodium salt (Fig. 52b).

Reprinted from [191]. Copyright 2017 with permission from Elsevier

Top: comparison of color acetonitrile solution of 109 in the presence of Et3N and both Et3N and LiClO4. Bottom: a UV–Vis titration of 109 (7.2 × 10−5 M) with LiClO4 (0-5.5 × 10−2 M) in pure acetonitrile. Dashed lines are spectra registered upon addition to the titrated system solution of Et3N (2.8 × 10−2 M); b UV–Vis spectra showing the competitive binding of lithium by 109 in the presence of sodium salt and triethylamine in acetonitrile. Number of compound in reproduced material correspond to following number of compound in this work: 3 = 109.

16-Membered crown without phenyl substituents 75 (Scheme 12) forms complexes both in neutral and basic acetonitrile solution. In pure acetonitrile the presence of alkali and alkaline earth metal cations causes a blue spectral shift corresponding to shift of tautomeric equilibrium and formation of complex in azophenol form. Under the same conditions no spectral changes were observed in the presence of lithium and sodium for 110. In basic acetonitrile (Et3N) for both 75 and 110 the presence of lithium and sodium salts (no changes in the presence of potassium) causes red shift of absorption band. This corresponds to formation of complexes by quinone-hydrazone forms. The comparison of the stability constants (logK), determined by UV–Vis titrations, of lithium and sodium complexes of 75 in neutral and basic acetonitrile and 110 in basic acetonitrile are shown in Fig. 53. Stability constant values of complexes of 23 in neutral acetonitrile were also included for comparison.