Abstract

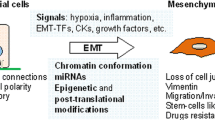

Cellular plasticity lies at the core of cancer progression, metastasis, and resistance to treatment. Stemness and epithelial-mesenchymal plasticity in cancer are concepts that represent a cancer cell’s ability to coopt and adapt normal developmental programs to promote survival and expansion. The cancer stem cell model states that a small subset of cancer cells with stem cell-like properties are responsible for driving tumorigenesis and metastasis while remaining especially resistant to common chemotherapeutic drugs. Epithelial-mesenchymal plasticity describes a cancer cell’s ability to transition between epithelial and mesenchymal phenotypes which drives invasion and metastasis. Recent research supports the existence of stable epithelial/mesenchymal hybrid phenotypes which represent highly plastic states with cancer stem cell characteristics. The cell adhesion molecule CD44 is a widely accepted marker for cancer stem cells, and it lies at a functional intersection between signaling networks regulating both stemness and epithelial-mesenchymal plasticity. CD44 expression is complex, with alternative splicing producing many isoforms. Interestingly, not only does the pattern of isoform expression change during transitions between epithelial and mesenchymal phenotypes in cancer, but these isoforms have distinct effects on cell behavior including the promotion of metastasis and stemness. The role of CD44 both downstream and upstream of signaling pathways regulating epithelial-mesenchymal plasticity and stemness make this protein a valuable target for further research and therapeutic intervention.

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

Not applicable.

References

Reya T, Morrison SJ, Clarke MF, Weissman IL (2001) “Stem cells, cancer, and cancer stem cells,” (in eng). Nature 414(6859):105–111. https://doi.org/10.1038/35102167

Dalerba P et al (2007) Phenotypic characterization of human colorectal cancer stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci 104(24):10158. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0703478104

Li C et al (2007) “Identification of pancreatic cancer stem cells,” (in eng). Cancer Res 67(3):1030–1037. https://doi.org/10.1158/0008-5472.can-06-2030

Zheng H et al (2018) “Single-cell analysis reveals cancer stem cell heterogeneity in hepatocellular carcinoma,” (in eng). Hepatology 68(1):127–140. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.29778

Boesch M et al (2016) “Heterogeneity of cancer stem cells: rationale for targeting the stem cell niche,” (in eng). Biochim Biophys Acta 1866(2):276–289. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbcan.2016.10.003

Hirata A, Hatano Y, Niwa M, Hara A, Tomita H (2019) “Heterogeneity in colorectal cancer stem cells,” (in eng). Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 12(7):413–420. https://doi.org/10.1158/1940-6207.capr-18-0482

Chaffer CL et al (2011) “Normal and neoplastic nonstem cells can spontaneously convert to a stem-like state,” (in eng). Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 108(19):7950–7955. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1102454108

Singh M, Yelle N, Venugopal C, Singh SK (2018) “EMT: mechanisms and therapeutic implications,” (in eng). Pharmacol Ther 182:80–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pharmthera.2017.08.009

Lu W, Kang Y (2019) “Epithelial-mesenchymal plasticity in cancer progression and metastasis,” (in eng). Dev Cell 49(3):361–374. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.devcel.2019.04.010

Nieto MA, Huang RY, Jackson RA, Thiery JP (2016) “EMT: 2016,” (in eng). Cell 166(1):21–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2016.06.028

Mani SA et al (2008) “The epithelial-mesenchymal transition generates cells with properties of stem cells,” (in eng). Cell 133(4):704–715. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2008.03.027

Li J, Zhou BP (2011) “Activation of β-catenin and Akt pathways by twist are critical for the maintenance of EMT associated cancer stem cell-like characters” (in eng). BMC Cancer. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2407-11-49

Sato R, Semba T, Saya H, Arima Y (2016) “Concise review: stem cells and epithelial-mesenchymal transition in cancer: biological implications and therapeutic targets,” (in eng). Stem Cells 34(8):1997–2007. https://doi.org/10.1002/stem.2406

Jolly MK et al (2015) “Implications of the hybrid epithelial/mesenchymal phenotype in metastasis,” (in eng). Front Oncol 5:155. https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2015.00155

Zheng X, Dai F, Feng L, Zou H, Xu M (2021) “Communication between epithelial-mesenchymal plasticity and cancer stem cells: new insights into cancer progression,” (in eng). Front Oncol 11:617597. https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2021.617597

Xu H et al (2015) “The role of CD44 in epithelial-mesenchymal transition and cancer development,” (in eng). Onco Targets Ther 8:3783–3792. https://doi.org/10.2147/ott.s95470

Chen C, Zhao S, Karnad A, Freeman JW (2018) The biology and role of CD44 in cancer progression: therapeutic implications. J Hematol Oncol 11(1):64. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13045-018-0605-5

Williams ED, Gao D, Redfern A, Thompson EW (2019) “Controversies around epithelial-mesenchymal plasticity in cancer metastasis,” (in eng). Nat Rev Cancer 19(12):716–732. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41568-019-0213-x

Chaffer CL, Brennan JP, Slavin JL, Blick T, Thompson EW, Williams ED (2006) “Mesenchymal-to-epithelial transition facilitates bladder cancer metastasis: role of fibroblast growth factor receptor-2,” (in eng). Cancer Res 66(23):11271–11278. https://doi.org/10.1158/0008-5472.can-06-2044

Saha B et al (2007) “Overexpression of E-cadherin protein in metastatic breast cancer cells in bone” (in eng). Anticancer Res 27(6):3903–3908

Kowalski PJ, Rubin MA, Kleer CG (2003) “E-cadherin expression in primary carcinomas of the breast and its distant metastases,” (in eng). Breast Cancer Res 5(6):R217–R222. https://doi.org/10.1186/bcr651

Chao Y, Wu Q, Acquafondata M, Dhir R, Wells A (2012) “Partial mesenchymal to epithelial reverting transition in breast and prostate cancer metastases,” (in eng). Cancer Microenviron 5(1):19–28. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12307-011-0085-4

Thiery JP, Acloque H, Huang RY, Nieto MA (2009) “Epithelial-mesenchymal transitions in development and disease,” (in eng). Cell 139(5):871–890. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2009.11.007

Zheng X et al (2015) “Epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition is dispensable for metastasis but induces chemoresistance in pancreatic cancer,” (in eng). Nature 527(7579):525–530. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature16064

Krebs AM et al (2017) “The EMT-activator Zeb1 is a key factor for cell plasticity and promotes metastasis in pancreatic cancer,” (in eng). Nat Cell Biol 19(5):518–529. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncb3513

Bornes L, Belthier G, van Rheenen J (2021) “Epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition in the light of plasticity and hybrid E/M states,” (in eng). J Clin Med 10(11):2403. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm10112403

Bhatia S, Monkman J, Toh AKL, Nagaraj SH, Thompson EW (2017) “Targeting epithelial-mesenchymal plasticity in cancer: clinical and preclinical advances in therapy and monitoring,” (in eng). Biochem J 474(19):3269–3306. https://doi.org/10.1042/bcj20160782

Jolly MK et al (2016) “Stability of the hybrid epithelial/mesenchymal phenotype,” (in eng). Oncotarget 7(19):27067–27084. https://doi.org/10.18632/oncotarget.8166

Puram SV et al (2017) “Single-cell transcriptomic analysis of primary and metastatic tumor ecosystems in head and neck cancer,” (in eng). Cell 171(7):1611-1624.e24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2017.10.044

Karacosta LG et al (2019) “Mapping lung cancer epithelial-mesenchymal transition states and trajectories with single-cell resolution,” (in eng). Nat Commun 10(1):5587. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-13441-6

Grosse-Wilde A et al (2015) Stemness of the hybrid epithelial/mesenchymal state in breast cancer and its association with poor survival. PLoS ONE 10(5):e0126522. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0126522

Strauss R et al (2011) “Analysis of epithelial and mesenchymal markers in ovarian cancer reveals phenotypic heterogeneity and plasticity” (in eng). PLoS One 6(1):16186. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0016186

Cook DP, Vanderhyden BC (2020) “Context specificity of the EMT transcriptional response” (in eng). Nat Commun 11(1):2142. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-16066-2

Pastushenko I et al (2018) Identification of the tumour transition states occurring during EMT. Nature 556(7702):463–468. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-018-0040-3

Pastushenko I et al (2021) “Fat1 deletion promotes hybrid EMT state, tumour stemness and metastasis,” (in eng). Nature 589(7842):448–455. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-020-03046-1

Kröger C et al (2019) “Acquisition of a hybrid E/M state is essential for tumorigenicity of basal breast cancer cells,” (in eng). Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 116(15):7353–7362. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1812876116

Stylianou N et al (2019) “A molecular portrait of epithelial-mesenchymal plasticity in prostate cancer associated with clinical outcome,” (in eng). Oncogene 38(7):913–934. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41388-018-0488-5

Ocaña OH et al (2012) “Metastatic colonization requires the repression of the epithelial-mesenchymal transition inducer Prrx1,” (in eng). Cancer Cell 22(6):709–724. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ccr.2012.10.012

Tsai JH, Donaher JL, Murphy DA, Chau S, Yang J (2012) “Spatiotemporal regulation of epithelial-mesenchymal transition is essential for squamous cell carcinoma metastasis,” (in eng). Cancer Cell 22(6):725–736. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ccr.2012.09.022

Yae T et al (2012) Alternative splicing of CD44 mRNA by ESRP1 enhances lung colonization of metastatic cancer cell. Nat Commun 3:883. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms1892

Beerling E et al (2016) “Plasticity between epithelial and mesenchymal states unlinks EMT from metastasis-enhancing stem cell capacity,” (in eng). Cell Rep 14(10):2281–2288. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep.2016.02.034

Celià-Terrassa T et al (2012) “Epithelial-mesenchymal transition can suppress major attributes of human epithelial tumor-initiating cells,” (in eng). J Clin Invest 122(5):1849–1868. https://doi.org/10.1172/jci59218

Li Y et al (2020) “Genetic fate mapping of transient cell fate reveals n-cadherin activity and function in tumor metastasis,” (in eng). Dev Cell 54(5):593-607.e5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.devcel.2020.06.021

Yu M et al (2013) “Circulating breast tumor cells exhibit dynamic changes in epithelial and mesenchymal composition,” (in eng). Science 339(6119):580–584. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1228522

Jolly MK et al (2019) Hybrid epithelial/mesenchymal phenotypes promote metastasis and therapy resistance across carcinomas. Pharmacol Therapeutics 194:161–184. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pharmthera.2018.09.007

Dang H, Ding W, Emerson D, Rountree CB (2011) “Snail1 induces epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition and tumor initiating stem cell characteristics” (in eng). BMC Cancer 11:396. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2407-11-396

Wellner U et al (2009) “The EMT-activator ZEB1 promotes tumorigenicity by repressing stemness-inhibiting microRNAs,” (in eng). Nat Cell Biol 11(12):1487–1495. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncb1998

Morel AP, Lièvre M, Thomas C, Hinkal G, Ansieau S, Puisieux A (2008) “Generation of breast cancer stem cells through epithelial-mesenchymal transition” (in eng). PLoS One 3(8):e2888. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0002888

Quan Q et al (2020) “Cancer stem-like cells with hybrid epithelial/mesenchymal phenotype leading the collective invasion,” (in eng). Cancer Sci 111(2):467–476. https://doi.org/10.1111/cas.14285

Marcucci F, Ghezzi P, Rumio C (2017) “The role of autophagy in the cross-talk between epithelial-mesenchymal transitioned tumor cells and cancer stem-like cells,” (in eng). Mol Cancer 16(1):3. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12943-016-0573-8

Garg M (2020) “Epithelial plasticity, autophagy and metastasis: potential modifiers of the crosstalk to overcome therapeutic resistance,” (in eng). Stem Cell Rev Rep 16(3):503–510. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12015-019-09945-9

Shibue T, Weinberg RA (2017) “EMT, CSCs, and drug resistance: the mechanistic link and clinical implications,” (in eng). Nat Rev Clin Oncol 14(10):611–629. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrclinonc.2017.44

Marín-Aguilera M et al (2014) “Epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition mediates docetaxel resistance and high risk of relapse in prostate cancer,” (in eng). Mol Cancer Ther 13(5):1270–1284. https://doi.org/10.1158/1535-7163.mct-13-0775

Creighton CJ et al (2009) “Residual breast cancers after conventional therapy display mesenchymal as well as tumor-initiating features,” (in eng). Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106(33):13820–13825. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0905718106

Redfern AD, Spalding LJ, Thompson EW (2018) “The Kraken Wakes: induced EMT as a driver of tumour aggression and poor outcome,” (in eng). Clin Exp Metastasis 35(4):285–308. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10585-018-9906-x

Gallatin WM, Weissman IL, Butcher EC (1983) A cell-surface molecule involved in organ-specific homing of lymphocytes. Nature 304(5921):30–34. https://doi.org/10.1038/304030a0

Ponta H, Sherman L, Herrlich PA (2003) “CD44: from adhesion molecules to signalling regulators,” (in eng). Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 4(1):33–45. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrm1004

Oppenheimer-Marks N, Davis LS, Lipsky PE (1990) “Human T lymphocyte adhesion to endothelial cells and transendothelial migration. Alteration of receptor use relates to the activation status of both the T cell and the endothelial cell,” (in eng). J Immunol 145(1):140–148

Zöller M (2011) CD44: can a cancer-initiating cell profit from an abundantly expressed molecule? Nat Rev Cancer 11(4):254–267. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrc3023

Al-Hajj M, Wicha MS, Benito-Hernandez A, Morrison SJ, Clarke MF (2003) “Prospective identification of tumorigenic breast cancer cells,” (in eng). Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 100(7):3983–3988. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0530291100

Patrawala L et al (2006) “Highly purified CD44+ prostate cancer cells from xenograft human tumors are enriched in tumorigenic and metastatic progenitor cells,” (in eng). Oncogene 25(12):1696–1708. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.onc.1209327

Zhao S et al (2016) “CD44 expression level and isoform contributes to pancreatic cancer cell plasticity, invasiveness, and response to therapy,” (in eng). Clin Cancer Res 22(22):5592–5604. https://doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-15-3115

Screaton GR, Bell MV, Jackson DG, Cornelis FB, Gerth U, Bell JI (1992) “Genomic structure of DNA encoding the lymphocyte homing receptor CD44 reveals at least 12 alternatively spliced exons,” (in eng). Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 89(24):12160–12164. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.89.24.12160

Azevedo R et al (2018) “CD44 glycoprotein in cancer: a molecular conundrum hampering clinical applications,” (in eng). Clin Proteomics 15:22–22. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12014-018-9198-9

Screaton GR, Bell MV, Bell JI, Jackson DG (2021) “The identification of a new alternative exon with highly restricted tissue expression in transcripts encoding the mouse Pgp-1 (CD44) homing receptor. Comparison of all 10 variable exons between mouse, human, and rat,” (in eng). J Biol Chem 268(17):12235–8

Roy Burman D, Das S, Das C, Bhattacharya R (2021) “Alternative splicing modulates cancer aggressiveness: role in EMT/metastasis and chemoresistance,” (in eng). Mol Biol Rep 48(1):897–914. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11033-020-06094-y

Bánky B, Rásó-Barnett L, Barbai T, Tímár J, Becságh P, Rásó E (2012) Characteristics of CD44 alternative splice pattern in the course of human colorectal adenocarcinoma progression. Mol Cancer 11(1):83. https://doi.org/10.1186/1476-4598-11-83

Bonnal SC, López-Oreja I, Valcárcel J (2020) Roles and mechanisms of alternative splicing in cancer—implications for care. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 17(8):457–474. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41571-020-0350-x

Prochazka L, Tesarik R, Turanek J (2014) “Regulation of alternative splicing of CD44 in cancer,” (in eng). Cell Signal 26(10):2234–2239. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cellsig.2014.07.011

Warzecha CC, Sato TK, Nabet B, Hogenesch JB, Carstens RP (2009) “ESRP1 and ESRP2 are epithelial cell-type-specific regulators of FGFR2 splicing,” (in eng). Mol Cell 33(5):591–601. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molcel.2009.01.025

Preca BT et al (2015) A self-enforcing CD44s/ZEB1 feedback loop maintains EMT and stemness properties in cancer cells. Int J Cancer 137(11):2566–2577. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijc.29642

Reinke LM, Xu Y, Cheng C (2012) “Snail represses the splicing regulator epithelial splicing regulatory protein 1 to promote epithelial-mesenchymal transition,” (in eng). J Biol Chem 287(43):36435–36442. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M112.397125

Warzecha CC et al (2010) “An ESRP-regulated splicing programme is abrogated during the epithelial-mesenchymal transition,” (in eng). Embo j 29(19):3286–3300. https://doi.org/10.1038/emboj.2010.195

Cheng C, Sharp PA (2006) “Regulation of CD44 alternative splicing by SRm160 and its potential role in tumor cell invasion,” (in eng). Mol Cell Biol 26(1):362–370. https://doi.org/10.1128/MCB.26.1.362-370.2006

Watermann DO, Tang Y, Zur Hausen A, Jäger M, Stamm S, Stickeler E (2006) “Splicing factor Tra2-beta1 is specifically induced in breast cancer and regulates alternative splicing of the CD44 gene,” (in eng). Cancer Res 66(9):4774–80. https://doi.org/10.1158/0008-5472.can-04-3294

Loh TJ et al (2014) “SC35 promotes splicing of the C5–V6-C6 isoform of CD44 pre-mRNA,” (in eng). Oncol Rep 31(1):273–279. https://doi.org/10.3892/or.2013.2812

Goodison S, Urquidi V, Tarin D (1999) “CD44 cell adhesion molecules,” (in eng). Mol Pathol 52(4):189–196. https://doi.org/10.1136/mp.52.4.189

Grimme HU et al (1999) “Colocalization of basic fibroblast growth factor and CD44 isoforms containing the variably spliced exon v3 (CD44v3) in normal skin and in epidermal skin cancers,” (in eng). Br J Dermatol 141(5):824–832. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2133.1999.03154.x

Ishimoto T et al (2011) “CD44 variant regulates redox status in cancer cells by stabilizing the xCT subunit of system xc(-) and thereby promotes tumor growth,” (in eng). Cancer Cell 19(3):387–400. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ccr.2011.01.038

Orian-Rousseau V, Chen L, Sleeman JP, Herrlich P, Ponta H (2002) “CD44 is required for two consecutive steps in HGF/c-Met signaling,” (in eng). Genes Dev 16(23):3074–3086. https://doi.org/10.1101/gad.242602

Matzke-Ogi A et al (2016) “Inhibition of tumor growth and metastasis in pancreatic cancer models by interference with CD44v6 signaling,” (in eng). Gastroenterology 150(2):513–25.e10. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2015.10.020

Ma L, Dong L, Chang P (2019) “CD44v6 engages in colorectal cancer progression,” (in eng). Cell Death Dis 10(1):30. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41419-018-1265-7

Bellerby R et al (2016) “Overexpression of specific CD44 isoforms is associated with aggressive cell features in acquired endocrine resistance,” (in eng). Front Oncol 6:145. https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2016.00145

Wang SJ, Wreesmann VB, Bourguignon LY (2007) “Association of CD44 V3-containing isoforms with tumor cell growth, migration, matrix metalloproteinase expression, and lymph node metastasis in head and neck cancer,” (in eng). Head Neck 29(6):550–558. https://doi.org/10.1002/hed.20544

Lokeshwar VB, Fregien N, Bourguignon LY (1994) “Ankyrin-binding domain of CD44(GP85) is required for the expression of hyaluronic acid-mediated adhesion function,” (in eng). J Cell Biol 126(4):1099–1109. https://doi.org/10.1083/jcb.126.4.1099

Yonemura S, Hirao M, Doi Y, Takahashi N, Kondo T, Tsukita S (1998) “Ezrin/radixin/moesin (ERM) proteins bind to a positively charged amino acid cluster in the juxta-membrane cytoplasmic domain of CD44, CD43, and ICAM-2,” (in eng). J Cell Biol 140(4):885–895. https://doi.org/10.1083/jcb.140.4.885

Legg JW, Isacke CM (1998) “Identification and functional analysis of the ezrin-binding site in the hyaluronan receptor, CD44,” (in eng). Curr Biol 8(12):705–708. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0960-9822(98)70277-5

Vuorio J et al (2021) N-glycosylation can selectively block or foster different receptor–ligand binding modes. Sci Rep 11(1):5239. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-84569-z

Zhou J et al (2019) CD44 expression predicts prognosis of ovarian cancer patients through promoting epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) by regulating snail, ZEB1, and caveolin-1. Front Oncol 9:802. https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2019.00802

Brown RL et al (2011) “CD44 splice isoform switching in human and mouse epithelium is essential for epithelial-mesenchymal transition and breast cancer progression,” (in eng). J Clin Invest 121(3):1064–1074. https://doi.org/10.1172/jci44540

Göttgens EL, Span PN, Zegers MM (2016) “Roles and regulation of epithelial splicing regulatory proteins 1 and 2 in epithelial-mesenchymal transition,” (in eng). Int Rev Cell Mol Biol 327:163–194. https://doi.org/10.1016/bs.ircmb.2016.06.003

Horiguchi K et al (2012) “TGF-β drives epithelial-mesenchymal transition through δEF1-mediated downregulation of ESRP,” (in eng). Oncogene 31(26):3190–3201. https://doi.org/10.1038/onc.2011.493

Tripathi V et al (2016) “Direct regulation of alternative splicing by SMAD3 through PCBP1 is essential to the tumor-promoting role of TGF-β,” (in eng). Mol Cell 64(3):549–564. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molcel.2016.09.013

Chen Q et al (2021) “TGF-β1 promotes epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition and stemness of prostate cancer cells by inducing PCBP1 degradation and alternative splicing of CD44,” (in eng). Cell Mol Life Sci 78(3):949–962. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00018-020-03544-5

Bhattacharya R, Mitra T, Ray Chaudhuri S, Roy SS (2018) Mesenchymal splice isoform of CD44 (CD44s) promotes EMT/invasion and imparts stem-like properties to ovarian cancer cells. J Cell Biochem 119(4):3373–3383. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcb.26504

Larsen JE et al (2016) ZEB1 drives epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition in lung cancer. J Clin Invest 126(9):3219–3235. https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI76725

Chen Q et al (2015) Poly r(C) binding protein-1 is central to maintenance of cancer stem cells in prostate cancer cells. Cell Physiol Biochem 35(3):1052–1061. https://doi.org/10.1159/000373931

Mima K et al (2012) “CD44s regulates the TGF-β-mediated mesenchymal phenotype and is associated with poor prognosis in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma,” (in eng). Cancer Res 72(13):3414–3423. https://doi.org/10.1158/0008-5472.can-12-0299

Okabe H et al (2014) CD44s signals the acquisition of the mesenchymal phenotype required for anchorage-independent cell survival in hepatocellular carcinoma. Br J Cancer 110(4):958–966. https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2013.759

Mima K et al (2013) High CD44s expression is associated with the EMT expression profile and intrahepatic dissemination of hepatocellular carcinoma after local ablation therapy. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci 20(4):429–434. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00534-012-0580-0

Dang H, Steinway SN, Ding W, Rountree CB (2015) “Induction of tumor initiation is dependent on CD44s in c-Met+ hepatocellular carcinoma,” (in eng). BMC Cancer 15:161. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-015-1166-4

Miwa T, Nagata T, Kojima H, Sekine S, Okumura T (2017) Isoform switch of CD44 induces different chemotactic and tumorigenic ability in gallbladder cancer. Int J Oncol 51(3):771–780. https://doi.org/10.3892/ijo.2017.4063

Wang Z et al (2019) “The prognostic and clinical value of CD44 in colorectal cancer: a meta-analysis,” (in eng). Front Oncol 9:309. https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2019.00309

Cho SH et al (2012) CD44 enhances the epithelial-mesenchymal transition in association with colon cancer invasion. Int J Oncol 41(1):211–218. https://doi.org/10.3892/ijo.2012.1453

Fernández JC et al (2004) “CD44s expression in resectable colorectal carcinomas and surrounding mucosa,” (in eng). Cancer Invest 22(6):878–885. https://doi.org/10.1081/cnv-200039658

Bendardaf R et al (2006) “Comparison of CD44 expression in primary tumours and metastases of colorectal cancer,” (in eng). Oncol Rep 16(4):741–746

Kunimura T, Yoshida T, Sugiyama T, Morohoshi T (2009) “The relationships between loss of standard CD44 expression and lymph node, liver metastasis in T3 colorectal carcinoma,” (in eng). J Gastrointest Cancer 40(3–4):115–118. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12029-009-9100-0

Huh JW et al (2009) “Expression of standard CD44 in human colorectal carcinoma: association with prognosis,” (in eng). Pathol Int 59(4):241–246. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-1827.2009.02357.x

Sadeghi A, Roudi R, Mirzaei A, Zare Mirzaei A, Madjd Z, Abolhasani M (2019) “CD44 epithelial isoform inversely associates with invasive characteristics of colorectal cancer” (in eng). Biomark Med 13(6):419–426. https://doi.org/10.2217/bmm-2018-0337

Mashita N et al (2014) “Epithelial to mesenchymal transition might be induced via CD44 isoform switching in colorectal cancer,” (in eng). J Surg Oncol 110(6):745–751. https://doi.org/10.1002/jso.23705

Pires BR et al (2017) “NF-kappaB is involved in the regulation of EMT genes in breast cancer cells,” (in eng). PLoS ONE 12(1):e0169622. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0169622

Smith SM, Cai L (2012) “Cell specific CD44 expression in breast cancer requires the interaction of AP-1 and NFκB with a novel cis-element,” (in eng). PLoS ONE 7(11):e50867. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0050867

Smith SM, Lyu YL, Cai L (2014) “NF-κB affects proliferation and invasiveness of breast cancer cells by regulating CD44 expression,” (in eng). PLoS ONE 9(9):e106966. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0106966

Dongre A, Weinberg RA (2019) “New insights into the mechanisms of epithelial-mesenchymal transition and implications for cancer,” (in eng). Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 20(2):69–84. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41580-018-0080-4

Zhan T, Rindtorff N, Boutros M (2017) “Wnt signaling in cancer,” (in eng). Oncogene 36(11):1461–1473. https://doi.org/10.1038/onc.2016.304

Wang L et al (2015) “ATDC induces an invasive switch in KRAS-induced pancreatic tumorigenesis,” (in eng). Genes Dev 29(2):171–183. https://doi.org/10.1101/gad.253591.114

Schmitt M, Metzger M, Gradl D, Davidson G, Orian-Rousseau V (2015) CD44 functions in Wnt signaling by regulating LRP6 localization and activation. Cell Death Differ 22(4):677–689. https://doi.org/10.1038/cdd.2014.156

Xia P, Xu X-Y (2015) “PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling pathway in cancer stem cells: from basic research to clinical application,” (in eng). Am J Cancer Res 5(5):1602–1609

Grille SJ et al (2003) “The protein kinase Akt induces epithelial mesenchymal transition and promotes enhanced motility and invasiveness of squamous cell carcinoma lines,” (in eng). Cancer Res 63(9):2172–2178

Todaro M et al (2014) “CD44v6 is a marker of constitutive and reprogrammed cancer stem cells driving colon cancer metastasis,” (in eng). Cell Stem Cell 14(3):342–356. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.stem.2014.01.009

Jolly MK et al (2018) “Interconnected feedback loops among ESRP1, HAS2, and CD44 regulate epithelial-mesenchymal plasticity in cancer,” (in eng). APL Bioeng 2(3):031908. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.5024874

Senbanjo LT, Chellaiah MA (2017) CD44: a multifunctional cell surface adhesion receptor is a regulator of progression and metastasis of cancer cells. Front Cell Dev Biol 5:18. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcell.2017.00018

Chen C, Zhao S, Karnad A, Freeman JW (2018) The biology and role of CD44 in cancer progression: therapeutic implications. J Hematol Oncol 11(1):64. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13045-018-0605-5

Orian-Rousseau V, Ponta H (2015) Perspectives of CD44 targeting therapies. Arch Toxicol 89(1):3–14. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00204-014-1424-2

Sauter A et al (2007) Pharmacokinetics, immunogenicity and safety of bivatuzumab mertansine, a novel CD44v6-targeting immunoconjugate, in patients with squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Int J Oncol 30(4):927–935

Rupp U et al (2007) Safety and pharmacokinetics of bivatuzumab mertansine in patients with CD44v6-positive metastatic breast cancer: final results of a phase I study. Anticancer Drugs 18(4):477–485. https://doi.org/10.1097/CAD.0b013e32801403f4

Menke-van der Houven CW, van Oordt CG et al (2016) First-in-human phase I clinical trial of RG7356, an anti-CD44 humanized antibody, in patients with advanced, CD44-expressing solid tumors. Oncotarget 7(48):80046–80058. https://doi.org/10.1832/oncotarget.11098

Uchino M et al (2010) Nuclear beta-catenin and CD44 upregulation characterize invasive cell populations in non-aggressive MCF-7 breast cancer cells. BMC Cancer 10:414. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2407-10-414

Murphy JF, Lennon F, Steele C, Kelleher D, Fitzgerald D, Long AC (2005) Engagement of CD44 modulates cyclooxygenase induction, VEGF generation, and proliferation in human vascular endothelial cells. FASEB J 19(3):446–448. https://doi.org/10.1096/fj.03-1376fje

Handorean AM, Yang K, Robbins EW, Flaig TW, Iczkowski KA (2009) Silibinin suppresses CD44 expression in prostate cancer cells. Am J Transl Res 1(1):80–86

Patel S et al (2014) Silibinin, a natural blend In polytherapy formulation For targeting Cd44v6 expressing colon cancer stem cells. Sci Rep 8(1):16985. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-35069-0

Iida J et al (2014) DNA aptamers against exon v10 of CD44 inhibit breast cancer cell migration. PLoS ONE 9(2):e88712. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0088712

Ababneh N et al (2013) In vitro selection of modified RNA aptamers against CD44 cancer stem cell marker. Nucleic Acid Ther 23(6):401–407. https://doi.org/10.1089/nat.2013.0423

Pecak A et al (2020) Anti-CD44 DNA aptamers selectively target cancer cells. Nucleic Acid Ther 30(5):289–298. https://doi.org/10.1089/nat.2019.0833

Ahrens T et al (2001) Soluble CD44 inhibits melanoma tumor growth by blocking cell surface CD44 binding to hyaluronic acid. Oncogene 20(26):3399–3408. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.onc.1204435

Pall T, Gad A, Kasak L, Drews M, Stromblad S, Kogerman P (2004) Recombinant CD44-HABD is a novel and potent direct angiogenesis inhibitor enforcing endothelial cell-specific growth inhibition independently of hyaluronic acid binding. Oncogene 23(47):7874–7881. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.onc.1208083

Tijink BM et al (2006) A phase I dose escalation study with anti-CD44v6 bivatuzumab mertansine in patients with incurable squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck or esophagus. Clin Cancer Res 12(20 Pt 1):6064–6072. https://doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-0910

Raso-Barnett L, Banky B, Barbai T, Becsagh P, Timar J, Raso E (2013) “Demonstration of a melanoma-specific CD44 alternative splicing pattern that remains qualitatively stable, but shows quantitative changes during tumour progression,” (in eng). PLoS ONE 8(1):e53883–e53883. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0053883

Mima K et al (2012) CD44s regulates the TGF-beta-mediated mesenchymal phenotype and is associated with poor prognosis in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Res 72(13):3414–3423. https://doi.org/10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-0299

Dang H, Steinway SN, Ding W, Rountree CB (2015) Induction of tumor initiation is dependent on CD44s in c-Met(+) hepatocellular carcinoma. BMC Cancer. 15:161. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-015-1166-4

Riechelmann H et al (2008) Phase I trial with the CD44v6-targeting immunoconjugate bivatuzumab mertansine in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Oral Oncol 44(9):823–829. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oraloncology.2007.10.009

H.-L. Roche (2016) "A study of RO5429083 in patients with metastatic and/or locally advanced, CD44-expressing, malignant solid tumors," Clinicaltrails.gov, Clinical trial 2016.

Yang Y, Zhao X, Li X, Yan Z, Liu Z, Li Y (2017) Effects of anti-CD44 monoclonal antibody IM7 carried with chitosan polylactic acid-coated nano-particles on the treatment of ovarian cancer. Oncol Lett 13(1):99–104. https://doi.org/10.3892/ol.2016.5413

Patel S et al (2018) Silibinin, a natural blend in polytherapy formulation for targeting Cd44v6 expressing colon cancer stem cells. Sci Rep 8(1):16985. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-35069-0

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by BX002086 (VA merit), CA250383 (NIH/NCI), CA216746 (NIH/NCI) and Nebraska Research Initiative (NRI) to P.D.

Funding

This study was supported by BX002086 (VA merit), CA250383 (NIH/NCI), CA216746 (NIH/NCI) and Nebraska Research Initiative (NRI) to P.D.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

PD and MP: Conceptualization, PD, MP, SG: Writing, Review, and Editing, PD: Supervision, PD: Funding Acquisition. The author(s) read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

There are no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

Ethical approval

Not applicable.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

All authors have agreed to publish this manuscript.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Primeaux, M., Gowrikumar, S. & Dhawan, P. Role of CD44 isoforms in epithelial-mesenchymal plasticity and metastasis. Clin Exp Metastasis 39, 391–406 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10585-022-10146-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10585-022-10146-x