Abstract

Introduction

Aberrant expression of E-cadherin has been associated with the development of metastases in patients with breast cancer. Even though the expression of E-cadherin has been studied in primary breast tumors, little is known about its expression at the distant metastatic sites. We investigate the relationship between E-cadherin expression in primary breast carcinoma and their distant, non-nodal metastases.

Methods

Immunohistochemical analysis of E-cadherin was performed in tissues from 30 patients with primary invasive breast carcinoma and their distant metastases. E-cadherin expression was evaluated as normal or aberrant (decreased when compared with normal internal positive controls, or absent).

Results

Twenty-two (73%) invasive carcinomas were ductal, and eight (27%) were lobular. Of the primary invasive ductal carcinomas, 55% (12/22) had normal E-cadherin expression and 45% (10/22) had aberrant expression. All of the metastases expressed E-cadherin with the same intensity as (12 tumors) or with stronger intensity than (10 tumors) the corresponding primaries. Of the invasive lobular carcinomas, one of eight (12%) primary carcinomas and none of the metastases expressed E-cadherin in the cell membranes, but they accumulated the protein in the cytoplasm.

Conclusion

Aberrant E-cadherin expression is frequent in invasive ductal carcinomas that progress to develop distant metastases. Distant metastases consistently express E-cadherin, often more strongly than the primary tumor. Invasive lobular carcinomas have a different pattern of E-cadherin expression, suggesting a different role for E-cadherin in this form of breast carcinoma.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Tumor invasion with subsequent metastases is the major cause of morbidity and mortality in patients with cancer. For patients with breast cancer, the development of metastases is the most important prognostic factor, as almost all patients with distant metastasis succumb to the disease [1–3].

Numerous studies have linked aberrant expression of E-cadherin with the development of metastases in breast cancer and other cancers. E-cadherin is a transmembrane glycoprotein that mediates calcium-dependent intercellular adhesion and is specifically involved in epithelial cell-to-cell adhesion [4–6]. The E-cadherin gene, located on chromosome 16q22.1, is an important regulator of morphogenesis [7, 8]. In cancer, decreased E-cadherin expression is one of the alterations that characterizes the invasive phenotype, and the data support its role as a tumor suppressor gene [9–12]. Studies have shown that aberrant E-cadherin expression is associated with the acquisition of invasiveness and more advanced tumor stage for many cancers including lung cancer [13], prostate cancer [14, 15], gastric cancer [16], colorectal carcinoma [17], and breast cancer [18–20].

Normal ductal epithelial cells in the mammary gland strongly express E-cadherin protein in the cytoplasmic membrane [21, 22]. Some studies in breast cancer have demonstrated that aberrant E-cadherin expression is associated with high-grade, estrogen receptor (ER)-negative, and metastatic breast carcinomas, whereas other studies have failed to confirm these findings [22–24]. In the present article, we set out to determine and compare the expression patterns of E-cadherin in primary breast carcinomas and their distant, non-nodal metastases.

Materials and methods

Patient selection

Thirty patients with breast cancer who developed distant metastases were identified using a computerized database. Breast tissues from the primary carcinoma and the corresponding distant, non-nodal metastases were retrieved from the Surgical Pathology files in our institution, with Institutional Review Board approval.

We identified 30 cases of primary invasive breast carcinomas and 32 cases of distant metastases (two patients each had two metastatic sites). Hematoxylin and eosin stained slides were available for review in all cases. Primary invasive carcinomas were measured microscopically, and were classified as invasive ductal carcinoma, invasive lobular carcinoma or other special types according to well-accepted criteria [25, 26]. A histologic grade was assigned to each primary invasive carcinoma [27].

Immunohistochemistry

E-cadherin protein expression was studied by immunohistochemistry using specific monoclonal antibodies against E-cadherin (HEC-D10; Zymed Laboratories, San Francisco, CA, USA). For assessment of ER, progesterone receptor (PR) and HER2/neu expression, specific monoclonal antibodies for ER (Ventana Medical Systems, Tucson, AZ, USA), PR (DAKO, Carpinteria, CA, USA), and HER2/neu (Herceptest; DAKO) were used following the manufacturers' recommended dilutions.

Immunohistochemistry was performed using an automated immunostainer (Biotek Techmate 500; Ventana Medical Systems) as described previously [28]. Briefly, 5 μm-thick sections were cut onto glass slides from formalin-fixed, paraffin tissue blocks. Sections were deparaffinized and were microwaved (1000 W Model #MTC1080-2A; Frigidaire, Dublin, OH, USA) in a pressure cooker (Nordic Ware, Minneapolis, MN, USA) with 1 l of 10 mM citrate buffer (pH 6.0). The sections were subsequently cooled with the lid on for an additional 10 min. After removing the lid, the entire pressure cooker was filled with cold, running tap water for 2–3 min or until the slides were cool. At 36°C, the stainer sequentially added an inhibitor of endogenous peroxidase, the primary antibodies (32 min), a biotinylated secondary antibody, an avidin–biotin complex with horseradish peroxidase, 3,3'-diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride, and copper enhancer. The slides were then counter-stained with hematoxylin.

Interpretation of immunohistochemical analysis

E-cadherin expression was interpreted as either normal (strong) or aberrant (reduced or absent) [29]. Internal positive controls, such as benign breast lobules and ducts, were present in most cases. Aberrant staining was defined as either negative staining or < 70% membranous staining of the population of cells examined. Normal staining was defined as ≥70% membranous staining of the cancer cells [29]. The ER and PR were considered positive when > 10% of the tumor cell nuclei were stained. For HER-2/neu, the strength of the membranous staining was recorded as 0, 1+ to 3+, and a sample was considered positive when 10% or more neoplastic cells had a staining intensity of ≥2+ [30].

Statistical analysis

Differences in percentages of E-cadherin-positive cases between the primary and metastatic groups were tested for statistical significance using Fisher's exact test. P < 0.05 was considered significant. A two-sample t test was also performed to compare the size, the ER, PR and HER-2/neu status, and the E-cadherin expression.

Results

Clinical and pathological features

The patients' characteristics are presented in Table 1. All patients were female.

The median age at diagnosis of the primary invasive breast carcinoma was 53.9 years (range, 39–80 years). All primary tumors were treated by surgical excision. Of the primary tumors, 22 were invasive ductal carcinomas and eight were invasive lobular carcinomas. Metastatic sites included the liver (six cases), the bone marrow (five cases), the skin (four cases), the lung (three cases), the femoral head (three cases), the pelvic girdle (two cases), the vertebrae (two cases), the brain (two cases), the colon (one case), the ovary (one case), the pericardium (one case), the abdominal wall (one case), and the contralateral breast (one case).

E-cadherin expression in primary and distant metastases

Normal breast epithelial cells were used as internal positive controls for E-cadherin staining in tissue sections. The glandular epithelium consistently demonstrated unequivocal and strong membranous staining localized at the cell borders. The nonepithelial components were negative for E-cadherin protein expression. Of the invasive ductal carcinomas, 55% (12/22) had normal E-cadherin expression and 45% (10/22) had aberrant E-cadherin protein expression. Of the distant metastases of ductal carcinomas, 70% (16/23) had normal E-cadherin expression and 30% (7/23) had aberrant expression.

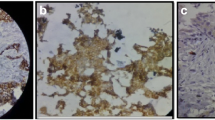

When we compared the staining intensity, all the metastatic cancer cells had E-cadherin expression equal to (13/23) or stronger than (10/23) the corresponding primary tumors. Figure 1 shows a primary invasive ductal carcinoma with aberrant E-cadherin expression that developed a metastasis to the iliac bone expressing normal levels of E-cadherin (or re-expression). Figure 2 shows examples of distant metastases of invasive ductal carcinomas with normal E-cadherin expression.

E-cadherin expression at the primary and distant metastatic sites. (A) and (B) Primary invasive ductal carcinoma with aberrant (reduced) E-cadherin expression. (C) This tumor metastasized 3 years later to the iliac bone. The metastatic carcinoma cells express normal levels of E-cadherin (re-expression). 200 × magnification.

E-cadherin is expressed at normal levels at the metastatic foci. Distant metastases from two different primary invasive ductal carcinomas to (A) the lung and (B) the bone. Note the crisp membranous staining for E-cadherin, which is specific for the cancer cells. Fibroblasts and other stromal cells are negative. 200 × magnification.

All invasive lobular carcinomas (eight cases) showed cytoplasmic staining and no protein in the cellular membrane (Fig. 3). Seventy-eight percent (7/9) of metastatic lobular carcinomas showed E-cadherin protein localized to the cytoplasm of the tumor cells. The other two metastatic foci of lobular carcinoma had normal E-cadherin expression (Table 2). No association was found between E-cadherin expression in primary invasive ductal carcinomas and the ER, PR and HER-2/neu status, the histologic grade, and the tumor size.

E-cadherin is accumulated in the cytoplasm of primary and metastatic lobular carcinomas of the breast. (A) and (B) Primary invasive lobular carcinoma invading fat. Notice the cellular discohesion and vacuolization typical of invasive lobular carcinomas. This tumor has cytoplasmic accumulation of E-cadherin. (C) Distant metastasis to the liver 8 years later exhibiting the pattern of E-cadherin expression as the primary tumor. 200 × magnification.

Discussion

The expression of E-cadherin in breast cancer metastases is largely unknown and, to our knowledge, there are no studies that specifically investigate the expression of E-cadherin in primary breast carcinomas in relationship to their distant metastases. We found that aberrant E-cadherin expression is a common event in primary invasive ductal carcinomas that progress to develop distant metastases, as aberrant expression was found in 45% of these cases.

There is increasing evidence that cancer cells may re-express E-cadherin protein once they reach distant sites. We found that all the metastatic deposits from invasive ductal carcinomas expressed E-cadherin, and the degree of expression was either equal to or stronger than that of the primary tumor. By studying E-cadherin expression in nodal breast cancer metastases, Bukholm and colleagues found that 19 of 20 lymph node metastases strongly expressed E-cadherin protein [21]. The mechanism and biologic role of E-cadherin re-expression at the metastatic site has not been elucidated, although it appears that translational regulation and post-translational events are probable mechanisms of E-cadherin re-expression [31].

In order to metastasize, cancer cells must break away from the primary tumor, move into the surrounding stroma, intravasate into the circulation, extravasate, and successfully re-establish growth at other sites. It is possible that loss of E-cadherin is a transient phenomenon that allows malignant cells to invade vascular channels and tissues. We have previously demonstrated that intralymphatic breast cancer emboli strongly express E-cadherin protein, and we postulate that re-expression of E-cadherin occurs in the circulating tumor cells, enabling the cancer cells to form tumor emboli and to survive [28]. E-cadherin re-expression may also enable malignant cells to form a metastatic deposit by facilitating intercellular adhesion. The normal expression or re-expression of E-cadherin in cancer metastases appears to be similar in breast cancer and prostate cancer. Rubin and colleagues studied a large group of prostate cancers that included 77 distant metastases and detected normal E-cadherin expression in 90% of these cases [29].

In breast cancer, a relationship between E-cadherin expression and ER expression has been noted previously. ER-positive tumors have been demonstrated to express normal amounts of E-cadherin protein, and loss of ER and E-cadherin genes has been linked to disease progression in invasive carcinomas of the breast. Nass and colleagues found an association between coincident methylation of E-cadherin and the ER gene during breast cancer progression, probably not attributable to coincidence of methylation for the two genes [32]. In our study, however, we did not find an association between E-cadherin expression and the ER, PR or HER-2/neu status.

The role of E-cadherin in the pathogenesis and progression of invasive lobular carcinoma is intriguing. We found that all of the primary invasive lobular carcinomas and nearly all of the metastatic foci had accumulation of E-cadherin protein in the cytoplasm of the neoplastic cells, with no membranous staining. Several studies have demonstrated that E-cadherin is commonly downregulated in invasive lobular carcinomas [33–36]. Berx and colleagues found somatic mutations of the E-cadherin gene in 56% (27/48 cases) of invasive lobular carcinomas, and 90% of these tumors had allelic losses at the E-cadherin locus. No mutations were identified in 50 nonlobular breast cancers [34]. Sarrio and colleagues recently reported that promoter hypermethylation is another common mechanism of E-cadherin inactivation in invasive lobular carcinomas, occurring in 41% (19/46) of cases [36]. De Leeuw and colleagues reported that 84% (32/38) of invasive lobular carcinomas had completely absent membranous staining by immunohistochemistry, and 56% of these cases had staining in the cytoplasm of the cancer cells [33].

The clearly different pattern of E-cadherin expression in invasive ductal and lobular carcinomas suggests that this protein may play different roles in the development of each specific type of tumor. The absence of membranous E-cadherin expression in invasive lobular carcinomas may determine the morphologic features such as the characteristic cellular discohesion of the lobular carcinoma cells, as well as the distinct pattern of stromal invasion of invasive lobular carcinomas, typically as single cells or rows of cells.

In summary, the present study provides evidence that approximately one-half of the invasive ductal carcinomas that develop distant metastases have aberrant E-cadherin protein expression. E-cadherin is expressed or re-expressed at the distant metastatic foci of invasive ductal carcinomas, supporting the hypothesis that re-expression of E-cadherin may play a role in the establishment of the metastatic cells at distant sites. Invasive lobular carcinomas have a different pattern of E-cadherin expression both at the primary carcinoma and the metastatic sites, which suggests a different role for E-cadherin in this form of breast cancer.

Conclusion

In the present study we specifically determine the expression of E-cadherin protein in primary invasive carcinomas and their corresponding distant metastases. We conclude that E-cadherin is expressed at normal levels at the distant metastatic site regardless of the level of expression at the primary invasive ductal carcinoma. This observation may have biological implications, as re-expression of E-cadherin may allow malignant cells to form the metastatic deposits. Invasive lobular carcinomas have a different pattern of E-cadherin expression both in the primary tumor and at the metastatic site.

Abbreviations

- ER:

-

estrogen receptor

- PR:

-

progesterone receptor.

References

Haybittle JL, Blamey RW, Elston CW, Johnson J, Doyle PJ, Campbell FC, Nicholson RI, Griffiths K: A prognostic index in primary breast cancer. Br J Cancer. 1982, 45: 361-366.

Rosen PR, Groshen S, Saigo PE, Kinne DW, Hellman S: A long-term follow-up study of survival in stage I (T1N0M0) and stage II (T1N1M0) breast carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 1989, 7: 355-366.

Danforth DN, Lichter A, Lippman ME: The diagnosis of breast cancer. In Diagnosis and Management of Breast Cancer. Edited by: Danforth Jr DN, Lichter A, Lippman ME. 1988, Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders, 50-94.

Gumbiner BM: Regulation of cadherin adhesive activity. J Cell Biol. 2000, 148: 399-404. 10.1083/jcb.148.3.399.

Deman JJ, Van Larebeke NA, Bruyneel EA, Bracke ME, Vermeulen SJ, Vennekens KM, Mareel MM: Removal of sialic acid from the surface of human MCF-7 mammary cancer cells abolishes E-cadherin-dependent cell–cell adhesion in an aggregation assay. In Vitro Cell Dev Biol Anim. 1995, 31: 633-639.

Shore EM, Nelson WJ: Biosynthesis of the cell adhesion molecule uvomorulin (E-cadherin) in Madin-Darby canine kidney epithelial cells. J Biol Chem. 1991, 266: 19672-19680.

Day ML, Zhao X, Vallorosi CJ, Putzi M, Powell CT, Lin C, Day KC: E-cadherin mediates aggregation-dependent survival of prostate and mammary epithelial cells through the retinoblastoma cell cycle control pathway. J Biol Chem. 1999, 274: 9656-9664. 10.1074/jbc.274.14.9656.

Peifer M: Beta-catenin as oncogene: the smoking gun. Science. 1997, 275: 1752-1753. 10.1126/science.275.5307.1752.

Gamallo C, Palacios J, Suarez A, Pizarro A, Navarro P, Quintanilla M, Cano A: Correlation of E-cadherin expression with differentiation grade and histological type in breast carcinoma. Am J Pathol. 1993, 142: 987-993.

Frixen UH, Behrens J, Sachs M, Eberle G, Voss B, Warda A, Lochner D, Birchmeier W: E-cadherin-mediated cell–cell adhesion prevents invasiveness of human carcinoma cells. J Cell Biol. 1991, 113: 173-185.

Pierceall WE, Woodard AS, Morrow JS, Rimm D, Fearon ER: Frequent alterations in E-cadherin and alpha- and beta-catenin expression in human breast cancer cell lines. Oncogene. 1995, 11: 1319-1326.

Chen WC, Obrink B: Cell–cell contacts mediated by E-cadherin (uvomorulin) restrict invasive behavior of L-cells. J Cell Biol. 1991, 114: 319-327.

Shimoyama Y, Hirohashi S, Hirano S, Noguchi M, Shimosato Y, Takeichi M, Abe O: Cadherin cell-adhesion molecules in human epithelial tissues and carcinomas. Cancer Res. 1989, 49: 2128-2133.

Umbas R, Isaacs WB, Bringuier PP, Schaafsma HE, Karthaus HF, Oosterhof GO, Debruyne FM, Schalken JA: Decreased E-cadherin expression is associated with poor prognosis in patients with prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 1994, 54: 3929-3933.

Umbas R, Isaacs WB, Bringuier PP, Xue Y, Debruyne FM, Schalken JA: Relation between aberrant alpha-catenin expression and loss of E-cadherin function in prostate cancer. Int J Cancer. 1997, 74: 374-377. 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0215(19970822)74:4<374::AID-IJC2>3.0.CO;2-S.

Mayer B, Johnson JP, Leitl F, Jauch KW, Heiss MM, Schildberg FW, Birchmeier W, Funke I: E-cadherin expression in primary and metastatic gastric cancer: down-regulation correlates with cellular dedifferentiation and glandular disintegration. Cancer Res. 1993, 53: 1690-1695.

Dorudi S, Hanby AM, Poulsom R, Northover J, Hart IR: Level of expression of E-cadherin mRNA in colorectal cancer correlates with clinical outcome. Br J Cancer. 1995, 71: 614-616.

Rasbridge SA, Gillett CE, Sampson SA, Walsh FS, Millis RR: Epithelial (E-) and placental (P-) cadherin cell adhesion molecule expression in breast carcinoma. J Pathol. 1993, 169: 245-250.

Oka H, Shiozaki H, Kobayashi K, Inoue M, Tahara H, Kobayashi T, Takatsuka Y, Matsuyoshi N, Hirano S, Takeichi M: Expression of E-cadherin cell adhesion molecules in human breast cancer tissues and its relationship to metastasis. Cancer Res. 1993, 53: 1696-1701.

Palacios J, Benito N, Pizarro A, Suarez A, Espada J, Cano A, Gamallo C: Anomalous expression of P-cadherin in breast carcinoma. Correlation with E-cadherin expression and pathological features. Am J Pathol. 1995, 146: 605-612.

Bukholm IK, Nesland JM, Borresen-Dale AL: Re-expression of E-cadherin, alpha-catenin and beta-catenin, but not of gamma-catenin, in metastatic tissue from breast cancer patients [see comments]. J Pathol. 2000, 190: 15-19. 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9896(200001)190:1<15::AID-PATH489>3.3.CO;2-C.

Bukholm IK, Nesland JM, Karesen R, Jacobsen U, Borresen-Dale AL: E-cadherin and alpha-, beta-, and gamma-catenin protein expression in relation to metastasis in human breast carcinoma. J Pathol. 1998, 185: 262-266. 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9896(199807)185:3<262::AID-PATH97>3.0.CO;2-Y.

Jones JL, Royall JE, Walker RA: E-cadherin relates to EGFR expression and lymph node metastasis in primary breast carcinoma. Br J Cancer. 1996, 74: 1237-1241.

Moll R, Mitze M, Frixen UH, Birchmeier W: Differential loss of E-cadherin expression in infiltrating ductal and lobular breast carcinomas. Am J Pathol. 1993, 143: 1731-1742.

Rosen PP, Oberman HA: Tumors of the Mammary Gland. Atlas of Tumor Pathology. 1993, Washington, DC: Armed Forces Institute of Pathology

Tavassoli F: General considerations in breast pathology. In Breast Pathology. Edited by: Tavassoli F. 1999, Connecticut: Appelton & Lange, 27-74.

Elston CW, Ellis IO: Pathological prognostic factors in breast cancer. I. The value of histological grade in breast cancer: experience from a large study with long-term follow-up. Histopathology. 1991, 19: 403-410.

Kleer CG, van Golen KL, Braun T, Merajver SD: Persistent E-cadherin expression in inflammatory breast cancer. Mod Pathol. 2001, 14: 458-464.

Rubin MA, Mucci NR, Figurski J, Fecko A, Pienta KJ, Day ML: E-cadherin expression in prostate cancer: a broad survey using high-density tissue microarray technology. Hum Pathol. 2001, 32: 690-697. 10.1053/hupa.2001.25902.

Seidman AD, Fornier MN, Esteva FJ, Tan L, Kaptain S, Bach A, Panageas KS, Arroyo C, Valero V, Currie V, Gilewski T, Theodoulou M, Moynahan ME, Moasser M, Sklarin N, Dickler M, D'Andrea G, Cristofanilli M, Rivera E, Hortobagyi GN, Norton L, Hudis CA: Weekly trastuzumab and paclitaxel therapy for metastatic breast cancer with analysis of efficacy by HER2 immunophenotype and gene amplification. J Clin Oncol. 2001, 19: 2587-2595.

Rashid MG, Sanda MG, Vallorosi CJ, Rios-Doria J, Rubin MA, Day ML: Posttranslational truncation and inactivation of human E-cadherin distinguishes prostate cancer from matched normal prostate. Cancer Res. 2001, 61: 489-492.

Nass SJ, Herman JG, Gabrielson E, Iversen PW, Parl FF, Davidson NE, Graff JR: Aberrant methylation of the estrogen receptor and E-cadherin 5' CpG islands increases with malignant progression in human breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2000, 60: 4346-4348.

De Leeuw WJ, Berx G, Vos CB, Peterse JL, Van de Vijver MJ, Litvinov S, Van Roy F, Cornelisse CJ, Cleton-Jansen AM: Simultaneous loss of E-cadherin and catenins in invasive lobular breast cancer and lobular carcinoma in situ. J Pathol. 1997, 183: 404-411. 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9896(199712)183:4<404::AID-PATH1148>3.0.CO;2-9.

Berx G, Cleton-Jansen AM, Nollet F, de Leeuw WJ, van de Vijver M, Cornelisse C, van Roy F: E-cadherin is a tumour/invasion suppressor gene mutated in human lobular breast cancers. Embo J. 1995, 14: 6107-6115.

Berx G, Cleton-Jansen AM, Strumane K, de Leeuw WJ, Nollet F, van Roy F, Cornelisse C: E-cadherin is inactivated in a majority of invasive human lobular breast cancers by truncation mutations throughout its extracellular domain. Oncogene. 1996, 13: 1919-1925.

Sarrio D, Moreno-Bueno G, Hardisson D, Sanchez-Estevez C, Guo M, Herman JG, Gamallo C, Esteller M, Palacios J: Epigenetic and genetic alterations of APC and CDH1 genes in lobular breast cancer: relationships with abnormal E-cadherin and catenin expression and microsatellite instability. Int J Cancer. 2003, 106: 208-215. 10.1002/ijc.11197.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by DOD grant DAMD 17-02-1-0490 and DAMD 17-02-0491 (CGK), and by a grant from the John and Suzanne Munn Endowed Research Fund of the University of Michigan Comprehensive Cancer Center (CGK).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

None declared.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kowalski, P.J., Rubin, M.A. & Kleer, C.G. E-cadherin expression in primary carcinomas of the breast and its distant metastases. Breast Cancer Res 5, R217 (2003). https://doi.org/10.1186/bcr651

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/bcr651