Abstract

Purpose

There is a strong need to improve the prognostication of breast cancer patients in order to prevent over- and undertreatment, especially when considering adjuvant chemotherapy. Tumour stroma characteristics might be valuable in predicting disease progression.

Methods

Studies regarding the prognostic value of tumour–stroma ratio (TSR) in breast cancer are evaluated.

Results

A high stromal content is related to a relatively poor prognosis. The most pronounced prognostic effect of this parameter seems to be observed in the triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) subtype.

Conclusions

TSR assessment might represent a simple, fast and reproducible prognostic factor at no extra costs, and could possibly be incorporated into routine pathological diagnostics. Despite these advantages, a robust clinical validation of this parameter has yet to be established in prospective studies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

According to the European cancer statistics for 2018, the estimated number of new breast cancer cases is 522.500 and the estimated number of deaths is 137.700 [1]. Breast tumours are classified in four molecular subtypes, namely luminal A, luminal B, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2)-enriched and basal-like [2, 3]. The triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) belongs to the basal-like phenotype in the vast majority, which is an aggressive form of breast cancer with a shorter relapse-free period (RFP) and relative survival compared to luminal A and B [4, 5]. However, gene-expression analyses have shown that this group is notoriously heterogeneous, with some molecular subtypes even associated with a relatively favourable prognosis [5]. Approximately 16% of all breast cancer cases are represented by TNBC [6].

In recent years, extensive research has been performed to discover new prognostic biomarkers and determine optimal prognostication schemes for breast cancer patients. Molecular tests, such as the 70-gene signature (MammaPrint, Agenda BV, The Netherlands) and the 21-gene assay (Oncotype DX, Genomic Health, United States), have shown to improve clinical decision making in early-stage breast cancer of certain molecular and clinical subtypes, such as oestrogen-positive (ER+) or HER2-negative (HER2−) breast cancer [7, 8]. These molecular markers are now endorsed into routine clinical practice, according to the American Society of Clinical Oncology Clinical Practice guideline, in order to reduce the administration of adjuvant chemotherapy and prevent overtreatment [9].

Despite the fact that alterations in the tumour microenvironment have been recognised as important drivers of tumour progression, the tumour environment has not been integrated in routine clinical decision making yet. A parameter which translates the amount of tumour-associated stroma is the tumour–stroma ratio (TSR), which has been extensively described as a rich source of prognostic information for various solid cancer types [10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38]. The TSR was first described as a prognostic factor in breast cancer in 2011 by De Kruijf et al. and has been validated in numerous studies [12,13,14,15, 17].

For the TSR assessment, the amount of tumour-associated stroma is determined on routine haematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stained slides of the primary tumour tissue. Each tumour is assigned to either the stroma-high or stroma-low category based on a set cut-off value [10].

In this review, literature investigating the effect of the TSR as a prognostic factor in female breast cancer is discussed with a special interest in the prognostic effect in TNBC patients.

Rationale

The influence of the tumour-associated stroma on epithelial tumour progression is mostly derived from functional in vitro studies. Similarly, those in vitro studies have demonstrated events in the stromal compartment that occur during carcinogenesis and could contribute to tumour progression. The production of growth factors and proteases by cancer cells initiate changes in the stromal environment [39]. Those alterations lie within remodelling of the matrix, recruitment of fibroblasts, the migration of immune cells and angiogenesis, all contributing to tumour progression [40]. Cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) contribute to carcinogenesis through the development of unique functions, including an amplified extracellular matrix (ECM) production, higher proliferation rate and the secretion of several cytokines, like vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), stromal cell-derived factor 1 (SDF1) and platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF), leading to angiogenesis [40]. Transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) is another factor that is thought to be strongly involved in the tumour-promoting effects of CAFs as described in colon cancer by Hawinkels et al. [41]. Those behavioural modifications lead to an elevated expression of enzymes, like matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), resulting in remodelling and deposition of the ECM, with concurrently the release of pro-angiogenic factors [42].

The ECM is frequently disorganised in tumours. One of the most important mechanisms in the ECM contributing to tumour progression is collagen crosslinking. Due to crosslinking collagen by lysyl oxidase (LOX), the ECM of the tumour becomes more stiff, leading to increased focal adhesions and enhanced PI3K signalling, thereby indirectly ensure tumour progression [43]. Besides the fact that alterations in the tumour niche lead to progression directly, the tumourigenesis can also be strengthened indirectly due to the aforementioned production of pro-angiogenic factors by CAFs and immune cells. Thus, during the process of tumourigenesis changes occur in the organisation of stromal cells, contributing both directly and indirectly to tumour growth and progression.

Previous studies investigating gene-expression profiles in stromal cells have demonstrated gene signatures related to clinical outcome and response to treatment in breast cancer [44, 45]. Clinical application of these signatures was impractical and a definitive indication was never discovered. These studies did provide a strong indication that valuable clinical information was ignored by solely focusing on the epithelial compartment. As the stromal processes that are reflected by these assays likely have a quantitative relationship with the amounts of stromal tissue within the tumour, quantitative stromal parameters might equally express prognostic information just by morphology alone [45].

Methods used for TSR assessment

In literature, two methods are described for TSR assessment in breast cancer: visual scoring, utilised by Mesker et al.; and automated point counting, a semi-automated approach, utilised by West et al. [10, 18].

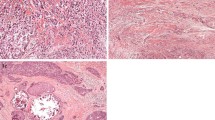

Visual eyeballing

Mesker et al. and others determined TSR by visual eyeballing [10, 12,13,14,15,16,17]. This microscopic determination of the amount of stroma in the primary tumour is performed on routine H&E stained slides. A 2.5 × or 5 × objective is used to determine the most stroma–abundant area on the slide. In this area, image fields with tumour cells at all borders of the image are used to determine the amount of stroma, using a 10 × objective. The stroma percentage is estimated in increments of 10% per image field, considering the highest scored stroma percentage as decisive. Stroma percentage ≤ 50% is categorised as stroma-low and a stroma percentage > 50% is categorised as stroma-high, based on statistical determination, initially performed on colon cancer and subsequently verified for breast cancer (Fig. 1) [10, 18]. Considerable segments of necrosis or in situ tumours were excluded in the evaluation of the TSR by neglecting them in the analysis [12, 14].

Semi-automated point counting

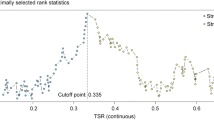

West and colleagues have objectified the measurement by evaluating the tumour tissue slides in colon carcinoma, using 300 random measurement points, validated for breast cancer by Downey et al. [18, 46, 47]. Four-micrometer-thick H&E stained sections are scanned, using a 20 × objective and subsequently two areas without large segments of necrosis are selected with a digital slide viewer. In this method, the two sampled 9 mm2 areas are in the tumour-leading edge, as well as in the non-leading edge. The group utilises a grid with a sample of 300 random points, superimposed on the selected area. Under each of the 300 points, the histopathology is categorised in ‘tumour’, ‘stroma’ or ‘unclassified’ (necrosis, blood vessels, inflammation etc.). The ultimate TSR is the proportion of ‘stroma’ under the 300 points, compared with all points per section. In other words, the TSR is the number of points, categorised as ‘stroma’ divided by the total number of points, categorised as ‘tumour’ and ‘unclassified’ [18, 46, 47]. Downey et al. have used 0.49 (i.e. 49%) as a cut-off value in their study in 2014, with ≥ 0.49 being stroma-high and < 0.49 stroma-low, based on statistical analysis [46]. However, in another study, cut-off values of 0.31 TSR for OS and 0.46 for DFS are used [47].

The inter-observer variation of these two methods, determined by the Cohen’s kappa coefficient (Κ) or intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC), lies in the range of 0.68–0.85, indicating substantial to good agreement between observers in both methods (Table 1).

Tumour–stroma ratio in breast cancer patients

The first study on TSR in breast cancer was published by De Kruijf et al. [12]. TSR was estimated by visual eyeballing according to the method described by Mesker et al. [10]. The authors showed that TSR was an independent prognostic parameter in 574 breast cancer patients with invasive breast tumours without distant metastasis (pT1–4, pN0–3, M0). Stroma-high tumours were associated with a worse RFP (Hazard Ratio (HR) 1.97, 95% Confidence Interval (CI) 1.47–2.64, P < 0.001) and overall survival (OS) (HR 1.50, 95% CI 1.18–1.91, P = 0.001) analysed with multivariate Cox regression analysis (Table 1) [12]. Vangangelt et al. analysed the prognostic value of TSR in a subset of the cohort of De Kruijf et al. in combination with immune status of tumours. Determination of classical human leukocyte antigen (HLA) class I, HLA-E, HLA-G, natural killer cells and/or regulatory T cells additional to TSR showed to have an even stronger prognostic effect [16].

Dekker et al. investigated the prognostic value of the amount of stroma determined by visual eyeballing in 403 premenopausal node-negative breast cancer patients (cT1–3) [14]. These patients were selected from the perioperative chemotherapy trial (POP trial, 10854) [48]. This study supported the earlier finding of TSR as an independent prognostic parameter for disease-free survival (DFS) (HR 1.85, 95% CI 1.33–2.59, P < 0.001) in favour of stroma-low tumours, and borderline statistical significance for OS (HR 1.60, 95% CI 1.00–2.57, P = 0.050) [14].

Gujam et al. investigated patients with invasive carcinoma of no special type (NST) (T1–3, N0–>3, grade I-III,) and subsequently found a correlation between stroma-high tumours and a poor 15-year cancer-specific survival (CSS) (HR 2.12, 95% CI 1.37–3.29, P = 0.001) in multivariate survival analysis after visual TSR assessment of H&E slides of 361 patients [15].

Downey et al. dispute this finding in his work by analysing the stromal content with semi-automated point counting [46]. They found that high tumour–stroma content in 118 women with ER+ grade 1–3 invasive breast tumours was independently associated with a better overall survival (OS) and relapse-free survival (RFS) (95% CI 0.2–0.7, P = 0.008 and 95% CI 0.1–0.6, P = 0.006, respectively) [46].

Following on their first study, Downey and colleagues investigated the stromal content in 45 patients with inflammatory breast cancer, a rare and aggressive form of breast cancer, using the semi-automated point counting method [47, 49]. However, no statistical significant difference was observed for this series (OS P = 0.53, DFS P = 0.66) [47].

Roeke et al. (T1–3, N0–2, grade I–III general BC) validated, by visual TSR assessment, that a high stromal content was a prognostic factor for worse OS (HR 1.56, 95% CI 1.18–2.05, P = 0.002), distant metastasis-free survival (DMFS) (HR 1.52, 95% CI 1.12–2.06, P = 0.008) and RFS (HR 1.35, 95% CI 1.01–1.81, P = 0.046), in their study of 737 patients with primary operable invasive breast cancer [17]. Unlike the work of Downey et al., patients with ER + stroma-high tumours were associated with a worse OS (HR 1.43, 95% CI 1.04–1.99, P = 0.030) [17].

Tumour–stroma ratio in triple-negative breast cancer

With respect to the applicability of TSR as a prognostic parameter in TNBC patients, a study has been performed by Moorman et al. in 2012. They analysed TSR in a retrospective cohort study consisting of triple-negative breast cancer patients (pT1–4, pN0–3 grade I–III) (N = 124) [13]. The amount of stroma was evaluated by visual eyeballing. Multivariate Cox regression analysis showed that the TSR was an independent prognostic factor for both RFP (HR 2.39, 95% CI 1.07–5.29, P = 0.033) and OS (HR 3.00, 95% CI 1.08–8.32, P = 0.034) in favour of stroma-low tumours. The 5-year RFP and OS for patients with stroma-low tumours compared to stroma-high tumours were 85% and 89% versus 45% and 65%, respectively [13].

A subgroup analysis for TNBC in the cohort of De Kruijf et al. of 82 TNBC patients supported the results of Moorman and colleagues that patients with stroma-high tumours had a significant shorter RFP (HR 2.92, 95% CI 1.36–6.32, P = 0.006) and OS (HR 1.87, 95% CI 1.07–3.26, P = 0.028) [12]. After 5 years of follow-up, 81% of the TNBC patients with stroma-low tumours were relapse free compared to 56% of patients with stroma-high tumours [12].

Among the 403 patients in the cohort of Dekker and colleagues, 69 patients were diagnosed with TNBC. Separate analyses of patients with stroma-high TNBC validated a 2.71 greater risk of developing a recurrence compared to patients with stroma-low TNBC (DFS; HR 2.71, 95% CI 1.11–6.61, P = 0.028) [14].

However, in the study of Gujam et al., the percentage of tumour–stroma was not found to be an independent prognostic factor for cancer-specific survival in 151 TNBC patients (P = 0.151) [15]. Likewise, Roeke et al. were not able to prove this correlation as well (P = 0.221) (Table 1) [17].

Tumour–stroma ratio in other subgroups

De Kruijf et al., Gujam et al. and Roeke et al. described the role of TSR in other subgroups. The results of De Kruijf et al. showed an independent prognostic value of TSR in patients who received only local therapy (P < 0.001), only adjuvant chemotherapy (P = 0.038) and only adjuvant endocrine therapy (P = 0.024) [12]. The latter was confirmed by Roeke et al. (P = 0.001) [17]. The same results were seen in patients with a TN tumour who received only local therapy (P = 0.006).

In non-TNBC patients (P = 0.013), ER-positive patients (P = 0.030) and HER2-negative tumours, the TSR was also of independent prognostic value [12, 17]. This was not the case for ER- and PR-negative breast tumours [17]. The last subgroup in which TSR was evaluated and proved to be statistical significant was node-negative tumours (P = 0.002 and P = 0.003) [15, 17]. A summary of these results is presented in Table 2.

Discussion of current literature

Extensive research has been performed to determine prognostic biomarkers for patient prognosis. Molecular tests, as MammaPrint and Oncotype DX, have seemed to be valuable for the improvement of clinical decision making in early-stage breast cancer [7, 8]. These tests will possibly be endorsed into routine clinical practice in order to reduce the administration of adjuvant chemotherapy and prevent overtreatment [9]. However, the disadvantages of the aforementioned molecular testing are the relatively high cost and the far mostly unknown influence of tumour heterogeneity. More specifically, intermingled non-tumour tissue may have a profound influence on the test results [50].

TSR has shown to be of prognostic value in addition to the traditional prognostic markers which are implemented in standard clinical care, for example, TNM stage, receptor status and HER2 expression, in breast cancer with a robust inter-observer variability. In Supplementary Tables 1 and 2, the effect of TSR in addition to the most important traditional prognostic markers is shown for the entire study population and triple-negative tumours, respectively.

So far, seven studies regarding TSR have been performed in the field of breast cancer, of which five have shown a significant association between high tumour–stroma content and a poor prognosis [12,13,14,15, 17]. However, the results of both studies of Downey and colleagues were not in line with the other five [46, 47]. As Downey et al. have determined the TSR in both studies with semi-automated point counting instead of visual eyeballing and have utilised different cut-off values, it may be concluded that a standardised estimation of TSR is essential for a robust method, applicable for patient management. The method of determining TSR differed considerably, resulting in underestimating the heterogeneity [51]. In contrast with previous studies, where the final TSR category is based on the highest stroma rate in the sample, Downey and colleagues scored only an area of 9 mm2 at the edge of the tumour [10, 46, 51, 52].

Although the difference in results can possibly be attributed to this inconsistency, the different breast cancer subgroups regarding basic characteristics must be taken in consideration as well. The applicability in the subtypes, namely TNBC, ER+ and inflammatory breast cancer, may differ and subsequently the individual relevance of the TSR has to be determined in different breast cancer subgroups, as is previously performed by Roeke and colleagues [17]. For example, in lobular carcinomas, the question is raised on how to determine which part is tumour-induced stroma or supportive stroma. This should be further determined in larger cohorts. With respect to TNBC, five studies have investigated this subgroup, of which three studies have shown significant results [12,13,14,15, 17]. The results of these three studies are rather promising regarding the prognostic effect of TSR [12,13,14]. However, two other studies have not validated this prognostic effect despite the favourable results earlier showed. As mentioned by Roeke et al., this discordance could possibly be contributed to the relatively low amount of stroma-high tumours in the TNBC subgroup [17]. The similar reason could be the cause for the effect of TSR in TNBC patients in the study of Gujam et al. [15]. Another explanation could be that the histological type of TNBC plays a role.

Although different studies researched the prognostic value of TSR, little is known about the composition of the stroma. Even when using conventional light microscopy, vast differences in stromal morphology can be appreciated which are surely reflective of enormous differences in stromal functionality. Molecular analyses have identified multiple molecular markers that are associated with varying degrees of stromal activation [53,54,55]. These findings might allow us to distinguish activated, highly tumour-promoting stromal tissues from non-activated or only mildly active stromal tissues. Future studies investigating stromal activation might therefore solely focus on specific highly active subsets of stromal tissues as opposed to counting all stromal tissues equally, thereby further refining this parameter: For instance, by identifying PA28 as a marker of stromal activation in a previous publication [53].

Similarly, Ahn et al. investigated the stromal composition of breast cancer tissue. Besides TSR, the dominant histological stroma type (collagen, fibroblast or lymphocytes) offers additional prognostic information. 5- and 10-year RFS rates were most favourable in the lymphocytic stroma type, followed by the fibroblast and collagen type. The latter was associated with the most aggressive tumour and consequently poorest prognosis [56]. Interestingly, Ahn et al. observed a trend between TNBC and a predominantly lymphocytic stroma type, with 56.1% of the samples being classified as ‘lymphocytic’. Considering the fact that TNBC has a relatively poor prognosis, the observed trend between TNBC and a predominantly lymphocytic stroma type, with a favourable prognosis, is striking. Leon-Ferre and colleagues showed similar results in early-stage TNBC in which the presence of low tumour-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) contributes to a poor prognosis [57].

Considering the aforementioned generally promising prognostic effect in TNBC, this subgroup is the most obvious candidate for further exploration of TSR. Currently, adjuvant systemic chemotherapy is advocated for all patients that present with operable TNBC due to the aggressive nature of this tumour subgroup. Regarding TNBC, unlike other molecular subtypes, there is no FDA approved targeted therapy yet. Forasmuch as both the aggressive nature of the subtype as the devoid of therapeutic options, supplementary research is necessary. In order to develop curative therapeutics in TNBC, stromal targets have to be determined. Given the fact that TNBC predominantly consists of lymphocytic stroma, according to Ahn and colleagues, the possible target might lie within this stroma. The quantity of programmed death ligand 1 (PD-L1), expressed on tumour cells, could be prognostic as well. Tomioka et al. have shown that low TILs in combination with high PD-L1 expression predict an unfavorable prognosis. Within the abundant lymphocytic stroma in TNBC, PD-L1 could possibly operate as a target for therapeutic options [58]. Thus, in further research, in addition to a standardised estimation of TSR, the biology or quality of the stroma should be taken into account as well, in both general breast cancer and especially in TNBC patients in order to clarify the paradox and subsequently to lay a foundation regarding targeted therapy.

Lastly, it should be noted that although previous studies demonstrated prognostic value in the past, these studies have always been performed as part of retrospective studies by researchers and pathologists with a specific interest in stromal tissues. Breast cancer is a heterogeneous disease and for this reason additional larger retrospective studies could add valuable information about the prognostic value of TSR in specific subgroups as well. Moreover, no prospective feasibility studies have been performed and as such, it remains to be seen whether broad application of this parameter would lead to reproducible test results. Current research efforts in this direction are however ongoing.

Conclusion

The current breast cancer prognostication schemes do not adequately predict patient prognosis. This leads to both over- and undertreatment with adjuvant chemotherapy. In order to better predict tumour biology and prevent unwarranted chemotherapy, additional prognostic parameters are necessary. TSR can be a valuable biomarker for determining patient prognosis. The scoring can be easily performed by the pathologist during routine pathological examination of H&E stained slides in less than a minute, with no additional costs, as it is a quick, simple method with a high reproducibility. The field of tumour–stroma provides promising perspectives, although standardisation of the methodology is desired. There is a trend towards high stromal content and a poor prognosis, being most applicable in TNBC. TSR in this case could be used to predict both disease progression and patient prognosis.

References

Ferlay J, Colombet M, Soerjomataram I, Dyba T, Randi G, Bettio M et al (2018) Cancer incidence and mortality patterns in Europe: estimates for 40 countries and 25 major cancers in 2018. Eur J Cancer. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2018.07.005

Carey LA, Perou CM, Livasy CA, Dressler LG, Cowan D, Conway K et al (2006) Race, breast cancer subtypes, and survival in the Carolina Breast Cancer Study. JAMA 295(21):2492–2502

Cancer Genome Atlas N (2012) Comprehensive molecular portraits of human breast tumours. Nature 490(7418):61–70

Engels CC, Kiderlen M, Bastiaannet E, Mooyaart AL, van Vlierberghe R, Smit VT et al (2016) The clinical prognostic value of molecular intrinsic tumor subtypes in older breast cancer patients: a FOCUS study analysis. Mol Oncol 10(4):594–600

Perou CM (2011) Molecular stratification of triple-negative breast cancers. Oncologist 16(1):61–70

de Kruijf EM, Bastiaannet E, Ruberta F, de Craen AJ, Kuppen PJ, Smit VT et al (2014) Comparison of frequencies and prognostic effect of molecular subtypes between young and elderly breast cancer patients. Mol Oncol 8(5):1014–1025

Cardoso F, van’t Veer LJ, Bogaerts J, Slaets L, Viale G, Delaloge S et al (2016) 70-gene signature as an aid to treatment decisions in early-stage breast cancer. N Engl J Med 375(8):717–729

Paik S, Shak S, Tang G, Kim C, Baker J, Cronin M et al (2004) A multigene assay to predict recurrence of tamoxifen-treated, node-negative breast cancer. N Engl J Med 351(27):2817–2826

Krop I, Ismaila N, Andre F, Bast RC, Barlow W, Collyar DE et al (2017) Use of biomarkers to guide decisions on adjuvant systemic therapy for women with early-stage invasive breast cancer: American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline focused update. J Clin Oncol 35(24):2838–2847

Mesker WE, Junggeburt JM, Szuhai K, de Heer P, Morreau H, Tanke HJ et al (2007) The carcinoma-stromal ratio of colon carcinoma is an independent factor for survival compared to lymph node status and tumor stage. Cell Oncol 29(5):387–398

Courrech Staal EF, Smit VT, van Velthuysen ML, Spitzer-Naaykens JM, Wouters MW, Mesker WE et al (2011) Reproducibility and validation of tumour stroma ratio scoring on oesophageal adenocarcinoma biopsies. Eur J Cancer 47(3):375–382

de Kruijf EM, van Nes JG, van de Velde CJ, Putter H, Smit VT, Liefers GJ et al (2011) Tumor–troma ratio in the primary tumor is a prognostic factor in early breast cancer patients, especially in triple-negative carcinoma patients. Breast Cancer Res Treat 125(3):687–696

Moorman AM, Vink R, Heijmans HJ, van der Palen J, Kouwenhoven EA (2012) The prognostic value of tumour–stroma ratio in triple-negative breast cancer. Eur J Surg Oncol 38(4):307–313

Dekker TJ, van de Velde CJ, van Pelt GW, Kroep JR, Julien JP, Smit VT et al (2013) Prognostic significance of the tumor–stroma ratio: validation study in node-negative premenopausal breast cancer patients from the EORTC perioperative chemotherapy (POP) trial (10854). Breast Cancer Res Treat 139(2):371–379

Gujam FJ, Edwards J, Mohammed ZM, Going JJ, McMillan DC (2014) The relationship between the tumour stroma percentage, clinicopathological characteristics and outcome in patients with operable ductal breast cancer. Br J Cancer 111(1):157–165

Vangangelt KMH, van Pelt GW, Engels CC, Putter H, Liefers GJ, Smit V et al Prognostic value of tumor–stroma ratio combined with the immune status of tumors in invasive breast carcinoma. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2017

Roeke T, Sobral-Leite M, Dekker TJA, Wesseling J, Smit V, Tollenaar R et al (2017) The prognostic value of the tumour–stroma ratio in primary operable invasive cancer of the breast: a validation study. Breast Cancer Res Treat 166(2):435–445

West NP, Dattani M, McShane P, Hutchins G, Grabsch J, Mueller W et al (2010) The proportion of tumour cells is an independent predictor for survival in colorectal cancer patients. Br J Cancer 102(10):1519–1523

Park JH, Richards CH, McMillan DC, Horgan PG, Roxburgh CS (2014) The relationship between tumour stroma percentage, the tumour microenvironment and survival in patients with primary operable colorectal cancer. Ann Oncol 25(3):644–651

Vogelaar FJ, van Pelt GW, van Leeuwen AM, Willems JM, Tollenaar RA, Liefers GJ et al (2016) Are disseminated tumor cells in bone marrow and tumor–stroma ratio clinically applicable for patients undergoing surgical resection of primary colorectal cancer? The Leiden MRD study. Cell Oncol (Dordr) 39(6):537–544

Aurello P, Berardi G, Giulitti D, Palumbo A, Tierno SM, Nigri G et al (2017) Tumor–Stroma Ratio is an independent predictor for overall survival and disease free survival in gastric cancer patients. Surgeon 15(6):329–335

Huijbers A, Tollenaar RA, v Pelt GW, Zeestraten EC, Dutton S, McConkey CC et al (2013) The proportion of tumor–stroma as a strong prognosticator for stage II and III colon cancer patients: validation in the VICTOR trial. Ann Oncol 24(1):179–185

Wang Z, Liu H, Zhao R, Zhang H, Liu C, Song Y (2013) Tumor–stroma ratio is an independent prognostic factor of non-small cell lung cancer. Zhongguo Fei Ai Za Zhi 16(4):191–196

Mesker WE, Liefers GJ, Junggeburt JM, van Pelt GW, Alberici P, Kuppen PJ et al (2009) Presence of a high amount of stroma and downregulation of SMAD4 predict for worse survival for stage I-II colon cancer patients. Cell Oncol 31(3):169–178

Wu J, Liang C, Chen M, Su W (2016) Association between tumor–stroma ratio and prognosis in solid tumor patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Oncotarget 7(42):68954–68965

Chen Y, Zhang L, Liu W, Liu X (2015) Prognostic significance of the tumor–stroma ratio in epithelial ovarian cancer. Biomed Res Int 2015:589301

Hansen TF, Kjaer-Frifeldt S, Lindebjerg J, Rafaelsen SR, Jensen LH, Jakobsen A et al (2018) Tumor–stroma ratio predicts recurrence in patients with colon cancer treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Acta Oncol 57(4):528–533

Li H, Yuan SL, Han ZZ, Huang J, Cui L, Jiang CQ et al (2017) Prognostic significance of the tumor–stroma ratio in gallbladder cancer. Neoplasma 64(4):588–593

Liu J, Liu J, Li J, Chen Y, Guan X, Wu X et al (2014) Tumor–stroma ratio is an independent predictor for survival in early cervical carcinoma. Gynecol Oncol 132(1):81–86

Lv Z, Cai X, Weng X, Xiao H, Du C, Cheng J et al (2015) Tumor–stroma ratio is a prognostic factor for survival in hepatocellular carcinoma patients after liver resection or transplantation. Surgery 158(1):142–150

Niranjan KC, Sarathy NA (2018) Prognostic impact of tumor–stroma ratio in oral squamous cell carcinoma: a pilot study. Ann Diagn Pathol 35:56–61

Pongsuvareeyakul T, Khunamornpong S, Settakorn J, Sukpan K, Suprasert P, Intaraphet S et al (2015) Prognostic evaluation of tumor–stroma ratio in patients with early stage cervical adenocarcinoma treated by surgery. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 16(10):4363–4368

Scheer R, Baidoshvili A, Zoidze S, Elferink MAG, Berkel AEM, Klaase JM et al (2017) Tumor–stroma ratio as prognostic factor for survival in rectal adenocarcinoma: a retrospective cohort study. World J Gastrointest Oncol 9(12):466–474

Wang K, Ma W, Wang J, Yu L, Zhang X, Wang Z et al (2012) Tumor–stroma ratio is an independent predictor for survival in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. J Thorac Oncol 7(9):1457–1461

Xi KX, Wen YS, Zhu CM, Yu XY, Qin RQ, Zhang XW et al (2017) Tumor–stroma ratio (TSR) in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) patients after lung resection is a prognostic factor for survival. J Thorac Dis 9(10):4017–4026

Zhang R, Song W, Wang K, Zou S (2017) Tumor–stroma ratio(TSR) as a potential novel predictor of prognosis in digestive system cancers: a meta-analysis. Clin Chim Acta 472:64–68

Zhang T, Xu J, Shen H, Dong W, Ni Y, Du J (2015) Tumor–stroma ratio is an independent predictor for survival in NSCLC. Int J Clin Exp Pathol 8(9):11348–11355

Zhang XL, Jiang C, Zhang ZX, Liu F, Zhang F, Cheng YF (2014) The tumor–stroma ratio is an independent predictor for survival in nasopharyngeal cancer. Oncol Res Treat 37(9):480–484

Mueller MM, Fusenig NE (2004) Friends or foes - bipolar effects of the tumour stroma in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer 4(11):839–849

Junttila MR, de Sauvage FJ (2013) Influence of tumour micro-environment heterogeneity on therapeutic response. Nature 501(7467):346–354

Hawinkels LJ, Paauwe M, Verspaget HW, Wiercinska E, van der Zon JM, van der Ploeg K et al (2014) Interaction with colon cancer cells hyperactivates TGF-beta signaling in cancer-associated fibroblasts. Oncogene 33(1):97–107

Bergers G, Brekken R, McMahon G, Vu TH, Itoh T, Tamaki K et al (2000) Matrix metalloproteinase-9 triggers the angiogenic switch during carcinogenesis. Nat Cell Biol 2(10):737–744

Levental KR, Yu H, Kass L, Lakins JN, Egeblad M, Erler JT et al (2009) Matrix crosslinking forces tumor progression by enhancing integrin signaling. Cell 139(5):891–906

Finak G, Bertos N, Pepin F, Sadekova S, Souleimanova M, Zhao H et al (2008) Stromal gene expression predicts clinical outcome in breast cancer. Nat Med 14(5):518–527

Farmer P, Bonnefoi H, Anderle P, Cameron D, Wirapati P, Becette V et al (2009) A stroma-related gene signature predicts resistance to neoadjuvant chemotherapy in breast cancer. Nat Med 15(1):68–74

Downey CL, Simpkins SA, White J, Holliday DL, Jones JL, Jordan LB et al (2014) The prognostic significance of tumour–stroma ratio in oestrogen receptor-positive breast cancer. Br J Cancer 110(7):1744–1747

Downey CL, Thygesen HH, Sharma N, Shaaban AM (2015) Prognostic significance of tumour stroma ratio in inflammatory breast cancer. Springerplus 4:68

Clahsen PC, van de Velde CJ, Julien JP, Floiras JL, Delozier T, Mignolet FY et al (1996) Improved local control and disease-free survival after perioperative chemotherapy for early-stage breast cancer. A European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Breast Cancer Cooperative Group Study. J Clin Oncol 14(3):745–753

Robertson FM, Bondy M, Yang W, Yamauchi H, Wiggins S, Kamrudin S et al (2010) Inflammatory breast cancer: the disease, the biology, the treatment. CA Cancer J Clin 60(6):351–375

Acs G, Kiluk J, Loftus L, Laronga C (2013) Comparison of Oncotype DX and Mammostrat risk estimations and correlations with histologic tumor features in low-grade, estrogen receptor-positive invasive breast carcinomas. Mod Pathol 26(11):1451–1460

Mesker WE, Dekker TJ, de Kruijf EM, Engels CC, van Pelt GW, Smit VT et al (2015) Comment on: The prognostic significance of tumour–stroma ratio in oestrogen receptor-positive breast cancer. Br J Cancer 112(11):1832–1833

Downey CL, Simpkins SA, Holliday DL, Jones JL, Jordan LB, Kulka J et al (2015) Reponse to: comment on, ‘Tumour–stroma ratio (TSR) in oestrogen-positive breast cancer patients’. Br J Cancer 112(11):1833–1834

Dekker TJ, Balluff BD, Jones EA, Schone CD, Schmitt M, Aubele M et al (2014) Multicenter matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization mass spectrometry imaging (MALDI MSI) identifies proteomic differences in breast-cancer-associated stroma. J Proteome Res 13(11):4730–4738

Witkiewicz AK, Dasgupta A, Sotgia F, Mercier I, Pestell RG, Sabel M et al (2009) An absence of stromal caveolin-1 expression predicts early tumor recurrence and poor clinical outcome in human breast cancers. Am J Pathol 174(6):2023–2034

Paulsson J, Sjoblom T, Micke P, Ponten F, Landberg G, Heldin CH et al (2009) Prognostic significance of stromal platelet-derived growth factor beta-receptor expression in human breast cancer. Am J Pathol 175(1):334–341

Ahn S, Cho J, Sung J, Lee JE, Nam SJ, Kim KM et al (2012) The prognostic significance of tumor-associated stroma in invasive breast carcinoma. Tumour Biol 33(5):1573–1580

Leon-Ferre RA, Polley MY, Liu H, Gilbert JA, Cafourek V, Hillman DW et al (2018) Impact of histopathology, tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes, and adjuvant chemotherapy on prognosis of triple-negative breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat 167(1):89–99

Tomioka N, Azuma M, Ikarashi M, Yamamoto M, Sato M, Watanabe KI et al (2018) The therapeutic candidate for immune checkpoint inhibitors elucidated by the status of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) and programmed death ligand 1 (PD-L1) expression in triple negative breast cancer (TNBC). Breast Cancer 25(1):34–42

Funding

This work was supported by Genootschap Keukenhof voor de Vroege Opsporing van Kanker, Lisse, The Netherlands. No grant number applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no potential conflict of interest.

Ethical standards

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Kramer, C.J.H., Vangangelt, K.M.H., van Pelt, G.W. et al. The prognostic value of tumour–stroma ratio in primary breast cancer with special attention to triple-negative tumours: a review. Breast Cancer Res Treat 173, 55–64 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-018-4987-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-018-4987-4