Purpose

The objective of this study was to investigate the correlation between the microscopic findings of positive lymph nodes, especially focusing on capsular invasion, and the outcome after curative surgical resection of colorectal cancer.

Methods

We analyzed 480 positive lymph nodes from 155 consecutive patients with Stage III colorectal cancer to determine the frequency and significance of lymph node capsular invasion. Recurrence-free and cancer-specific survival rates were assessed in the patients with and without lymph node capsular invasion.

Results

Between April 1995 and December 2000, 406 consecutive patients with primary colorectal cancer underwent curative resection. Regional lymph node metastases were present in 155 cases (38.2 percent). During the median follow-up period of 4.8 years, 41 patients (26.5 percent) developed recurrent disease and 28 patients died of cancer. Lymph node capsular invasion was detected in one or more lymph nodes from 75 cases (48.3 percent). The five-year recurrence-free rate was 56.1 percent in this group, whereas in the 80 patients without lymph node capsular invasion the rate was 88 percent (P<0.01). Features that were associated with recurrent disease were greater number of positive lymph nodes, venous invasion in primary tumor, infiltrative growth pattern of intranodal tumor, and presence of lymph node capsular invasion. Multivariate analysis identified lymph node capsular invasion as the only significant prognostic factor for recurrence. In multivariate analysis with regard to survival, lymph node capsular invasion, venous invasion, and number of positive nodes remained as significant prognostic factors.

Conclusions

Lymph node capsular invasion, determined by routine hematoxylin-eosin staining, is a potent prognostic factor in Stage III colorectal cancer.

Similar content being viewed by others

Lymph node involvement is an important prognostic factor in patients with colorectal cancer, and many studies have indicated that the number and location of metastatic nodes affect prognosis.1–4 In the latest TNM system,5,6 patients with histologically involved nodes have been subdivided into two groups: those with one to three involved nodes (N1), and those with four or more (N2).

Recently, new technologies have been developed, including immunohistochemistry and other special techniques, such as in situ hybridization, which allow the identification of carcinoma cells in lymph nodes, previously undetected by routine histology.7–9 These relatively new and highly sensitive approaches, although proved to be useful and valid in research settings, are not yet available in routine clinical practice. Moreover, the clinical significance of these findings is still controversial.

Routine histologic diagnosis is based only on the identification of cancer cells in lymph nodes. Pathologists diagnose the lymph nodes as positive or negative, but further meticulous morphologic investigation is rarely performed. Komuta et al.10 have reported the prognostic value of extracapsular invasion of positive lymph nodes in patients with resectable colorectal cancer; however, it seems that their method of categorization based on histopathologic findings is complex.

This study was designed to refine the prognostic subsets in Stage III colorectal cancer patients and, for this purpose, we retrospectively reviewed a consecutive series of patients who underwent curative resection and were histologically proved to be node-positive. All the positive lymph nodes were evaluated concerning the size and patterns of microscopic tumor growth, especially focusing on lymph node capsular invasion, and their prognostic value was investigated.

Patients and Methods

During the period from April 1995 to December 2000, 406 consecutive patients with primary colorectal cancer received curative (R0) resection at the Division of Colorectal Surgery, the International Medical Center of Japan. All patients had T1, T2, T3, or T4 adenocarcinoma, and patients with distant metastasis at the time of diagnosis and those with rectal cancer that had circumferential resection margin of <1 mm were excluded from the present study. Regional lymph node metastases were present in 155 cases (38.2 percent), which constituted the study group.

None of these 155 cases received any kind of neoadjuvant therapy, including preoperative radiation therapy. At that time, in our surgical division, there was no established protocol of adjuvant chemotherapy, and therefore, it was not routinely recommended to patients even if they were node-positive. Treatment with oral 5-fluorouracil alone was the most common protocol adopted.

The information extracted from the clinical record of each patient was as follows: date of birth; date of surgery; date of last follow-up; date of first recurrence; location of the primary tumor (cecum, ascending, transverse, descending, sigmoid colon, or rectum); site of first recurrence (liver, lung, local, bone, peritoneal, or other); administration of adjuvant therapy; and preoperative serum carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) level.

Follow-up was performed in accordance with the division’s protocol and was based on periodic evaluations of the patients, concerning the serum CEA levels (every 3 months), abdominal/pelvic CT scan or ultrasonography (every 6 months), and chest x-ray (every 12 months). The follow-up findings were confirmed for all patients on September 30, 2004.

Pathologic Review

As a part of our routine practice, specimens were delivered to the pathology division in the fresh state and, immediately after the operation, we grossly examined the specimens and dissected the lymph nodes by careful palpation.

The microscopic slides of all specimens and the surgical pathology reports were reviewed for the following information: tumor depth of invasion; tumor size (maximum diameter of the primary lesion); predominant histologic tumor grade (well, moderately, poorly differentiated, and mucinous); grade of lymphatic or venous invasion (focal or extensive); number of lymph nodes recovered; number of lymph nodes that contained metastases. If a tumor nodule of ≥3 mm in diameter was identified in the mesorectum or mesocolon and there was no histologic evidence of residual nodal tissue, it was classified as a regional lymph node metastasis, in accordance with the rules of the fifth edition of TNM staging.11

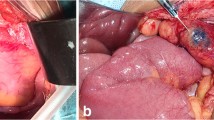

In addition to the routine pathologic examination, all of the positive lymph nodes were retrospectively reviewed and evaluated for the following findings: size of intranodal tumor (sum of tumor diameter in lymph nodes per case); pattern of tumor growth (infiltrative or expansive); and presence of capsular invasion (defined as growth of adenocarcinoma through or beyond the lymph node capsule and evaluated as present or absent; Fig. 1). We defined the size of intranodal tumor as the sum of maximum dimensions of the tumor nodules measured on the slide. If infiltrative tumor growth or capsular invasion was observed in at least one node, we categorized the case as “infiltrative” and, therefore, “with capsular invasion.” After the appearance of the node was characterized, interobserver agreement between the two independent observers (HY and YS, with 16 and 28 years, respectively, of experience in surgery) was measured.

Statistical Analysis

Recurrence-free period was defined as the interval from surgery to the time recurrent disease was diagnosed. For the evaluation of cancer-specific survival, only cancer-related deaths were considered events and data on the patients who died from other causes or who were still alive at the end of our study were censored. Recurrence-free and cancer-specific survival rates were calculated by the Kaplan-Meier method. The log-rank test was used to evaluate differences between survival curves. Univariate analysis was conducted with regard to the following variables: location, size, depth of invasion, tumor grade, and lymphovascular invasion of main tumors; number of positive nodes; and patterns of lymph node involvement. Multivariate analysis was performed for variables that were statistically significant in univariate analysis using the Cox proportional hazards model and stepwise logistic regression. Associations were analyzed using the chi-squared test or Fisher’s exact probability test (two-sided) for categoric variables and Mann-Whitney U test was used to compare means. Interobserver agreement for the microscopic assessment of intranodal tumor growth pattern or capsular invasion was assessed by use of the κ statistic. P<0.05 was considered a statistically significant association. Statistical analysis was performed with SPSS® software, version 12.0 (SPSS Japan Inc., Tokyo, Japan).

Results

Microscopic Findings

Of the 155 Stage III patients, the mean and median number of lymph nodes recovered per case was 29 and 27, respectively (range, 1–107). The mean and median number of positive lymph nodes per case was 3.1 and 2, respectively (range, 1–23). Fifty-six patients had one positive node, 45 patients had two, 12 patients had three, and 42 patients had four or more. A total of 480 positive nodes were examined.

The size of intranodal tumor per case ranged from 0.3 to 100 (median, 8) mm. Infiltrative growth pattern of intranodal tumor was observed in 86 cases (55.5 percent), whereas expansive growth pattern was seen in 69 cases (44.5 percent). Lymph node capsular invasion was present in 75 cases (48.4 percent) and absent in 80 cases (51.6 percent). Tumor nodules without histologic evidence of residual lymph node were observed in 17 cases (11 percent). Because all of them had an irregular contour or accompanied lymph nodes with capsular invasion, they were categorized into the capsular invasion positive group in this study. Interobserver agreement for assessing the microscopic findings of lymph nodes was 85 percent, with a κ score of 0.693.

Patient Characteristics

Table 1 shows the clinicopathologic features of 155 patients whose positive lymph nodes were analyzed for the presence of lymph node capsular invasion. The mean size of the primary tumor was 4.9 (range, 1.3–17) cm in maximum diameter. Six tumors were T1, 10 were T2, 133 were T3, and 6 were T4.

Clinical Outcomes

The overall median follow-up period was 4.9 years (range, 4 months to 8.9 years). All the patients with a follow-up period of less than one year were free of disease and died of causes other than cancer, and none of the patients died of surgical complications.

During this period, 41 cases (26.5 percent) among the 155 Stage III patients developed recurrent disease. Initial recurrence occurred in the liver in 20 cases, in the lungs in 9 cases, in the local regions (including anastomotic or pelvic recurrence) in 6 cases, in the peritoneum in 5 cases, and in other organs in 6 cases. The median time period until the recurrent disease became clinically apparent was 12 months (range, 2 months to 4.1 years). Twenty-eight cancer-related deaths were observed, and 16 patients died of other causes during the period.

The median follow-up period for those patients who did not develop recurrence was 5.4 years (range, 4 months to 8.9 years). The median follow-up period for those who were still alive was 5.5 years.

Analysis of Recurrence

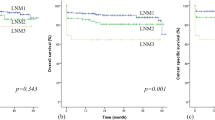

The features that were associated with recurrent disease in univariate analysis were as follows: higher grade of venous invasion; greater number (≥4) of positive lymph nodes; presence of lymph node capsular invasion; and infiltrative intranodal growth pattern. Figure 2 shows the Kaplan-Meier curves of recurrence-free rates for those features. Multivariate analysis using Cox proportional hazards model revealed lymph node capsular invasion to be the only significant prognostic factor associated with recurrence (hazard ratio, 3.812; 95 percent confidence interval, 1.638–8.871; Table 2). The five-year recurrence-free rates of patients with and without lymph node capsular invasion were 56.1 and 88 percent, respectively.

Among the 75 patients with lymph node capsular invasion, 32 patients developed recurrence, 26 of whom (81.3 percent) recurred in distant organs. Of the 80 patients without lymph node capsular invasion, on the other hand, only 9 recurred and 8 of them (88.9 percent) developed distant metastasis. No significant association was observed between lymph node capsular invasion and site of initial recurrence (distant or local).

Analysis of Survival

Univariate analysis for cancer-specific survival showed statistical association with the following features: higher grade of lymphatic and venous invasion; greater number (≥4) of positive lymph nodes; presence of lymph node capsular invasion; and infiltrative intranodal growth pattern. Among those, the following features remained as the significant prognostic factors associated with survival in multivariate analysis: lymph node capsular invasion; number of positive lymph nodes; and venous invasion (hazard ratio and 95 percent confidence interval are shown in Table 3). Kaplan-Meier curves of cancer-specific survival for those features are presented in Figure 3. The five-year survival rates of patients with and without lymph node capsular invasion were 70.4 and 90.5 percent, respectively.

Factors Associated with Lymph Node Capsular Invasion

The features that were associated with the presence of lymph node capsular invasion were as follows: depth of primary tumor; lymphatic and venous invasion; number of lymph node metastases; intranodal tumor growth pattern; and treatment with adjuvant chemotherapy (Table 1).

Discussion

In the current study, we identified a novel histopathologic finding that can serve as a significant prognostic determinant based on the biologic behavior of Stage III tumors. Our results show that lymph node capsular invasion, determined by routine histology, can be a more critical variable in predicting prognosis than other variables, such as T status, lymphovascular invasion, and number of positive nodes. They also indicate that patients with capsular invasion should be regarded as a high-risk group for recurrence and, therefore, should be the candidates for adjuvant chemotherapy along with intensive follow-up.

There are many investigators who have reported a close relationship between survival and number of involved lymph nodes.1–4,12,13 In the latest International Union Against Cancer/American Joint Committee on Cancer (UICC/AJCC) TNM staging,5,6 patients with histologically involved nodes have been subdivided into two groups: those with one to three involved nodes (N1), and those with four or more involved nodes (N2). Wong et al.14 reported that the number of involved nodes, rather than the volume of metastatic involvement of the regional lymph nodes, determines outcome and the presence or absence of nodal metastases represents the most important prognostic factor in colorectal cancer; our results are congruent with their report.

Although conventional prognostic factors, such as vascular invasion and number of positive nodes, proved to be associated with survival in both univariate and multivariate analyses in the present study, they did not have prognostic significance in multivariate analysis with regard to recurrence and lymph node capsular invasion remained as the only significant prognostic factor. These findings indicate that lymph node capsular invasion is a potent prognostic factor associated with recurrence.

The reason why capsular invasion is a significant prognostic factor for distant metastasis and local recurrence is unknown. Given that capsular invasion is associated with depth and lymphovascular invasion of primary tumor and number of positive nodes, it may represent the ability of colorectal tumor cells to disseminate to distant sites, which might be a process distinct from the ability to spread to local lymph nodes. Otherwise, tumor cells penetrate into vascular structures in the lymph node, leading to hematogenous dissemination, or drain into the efferent lymphatics of lymph nodes and eventually into the systemic circulation. In fact, lymph node capsular invasion was identified in all Stage IV patients who had their main tumor resected during the same period (data not shown).

Extracapsular extension of lymph node metastasis has been suggested to be of prognostic value in a variety of solid tumors, such as breast,15,16 head-and-neck,17,18 thyroid,19 prostate,20 skin,21 gynecologic,22 and gastrointestinal cancers.10,23,24 Local control, disease-free survival, and overall survival also may be affected in colorectal cancer.10,23,25 Komuta et al.10 have identified extracapsular invasion of the metastatic nodes as a useful and unfavorable prognostic factor in 84 colorectal cancer patients in terms of recurrence and survival, and our findings support their results. They have claimed, however, that no significant association was found between extracapsular invasion and other clinicopathologic features; moreover, no statistically significant difference was observed in recurrence or survival between N1 and N2 groups according to TNM classification. These observations may be attributable to a smaller number of patients in their study. Heide et al.23 have correlated extracapsular extension of nodal metastasis with poor local control in 96 patients with node-positive rectal cancer. In the present work, a larger number of patients with Dukes C colorectal cancer was examined and, to the best of our knowledge, no studies have previously evaluated the prognostic significance of lymph node capsular invasion using multivariate analysis.

Adequate retrieval and assessment of lymph nodes in colorectal cancer resection specimens is an important component of staging.26–29 The number of nodes examined in a specimen varies substantially from case to case, which is dependent on the anatomic variability or the different operative procedures, as well as on the extent or diligence of pathologic examination.13,26–31 Recent National Cancer Institute guidelines suggest that a minimum of 12 lymph nodes is required to accurately determine whether a patient has positive lymph nodes,32 and it is adopted by the TNM Classification of AJCC and UICC. The fat-clearance technique has been shown to increase the accuracy of lymph node harvest in surgical specimens compared with manual dissection.33,34 More recently, immunohistochemical or genetic techniques have been proposed to identify small clusters of cancer cells (“micrometastases”) within lymph nodes, and ultrastaging, by serial sectioning combined with immunohistochemical techniques, has improved detection of nodal micrometastasis.7–9,35–38 These techniques, however, are time-consuming and labor-intensive for routine clinical use. Moreover, consensus has not yet been achieved regarding the prognostic significance of micrometastasis or isolated tumor cells in lymph nodes identified by those special techniques.39–42 Originally, the Dukes classification and records developed during many decades at St. Mark’s Hospital were based on a single section through each node and so is the latest TNM classification.

In this study, lymph nodes were retrieved manually without fat clearance, a single section was obtained through each node, monoclonal antibodies were not used routinely, and tumor deposits without residual nodal tissue were counted as positive nodes in accordance with the fifth edition of UICC/AJCC staging guidelines. The mean time required to complete the retrieval was approximately 60 minutes. As a result, the median number of lymph nodes harvested in this study was 27, which is far more than those found using manual dissection in previous studies.26,27,29,43 This might be attributable to the extent of lymph node dissection and to our diligence in identifying nodes. Overall node-positive rate in our study population was 38.2 percent, which is consistent with that observed in other studies.27,29

Lymph node capsular invasion may represent various patterns of cancer invasion: afferent or efferent vessel invasion, hilar tissue invasion, or intranodal tumor extending beyond the capsule. It often is difficult to distinguish between them, unless tumor cells show focal invasion. Lymph nodes have unidirectional lymphatic flow, with most of the supply coming from the hilar vessels.15,44,45 Lymph flow enters the lymph node from the multiple afferent lymphatic vessels, into the subcapsular sinus, moves down the lymphatic sinuses, and leaves through the efferent lymphatic vessel in the hilum. Colorectal cancer cells may involve the afferent vessels of the lymph node, leading to direct extension from the afferent vessels to the subcapsular sinus. In addition, the tumor cells may involve the lymph node in a variety of patterns, intrasinusoidal or parenchymal, and also may involve the hilar tissue and efferent vessels. They might sometimes completely replace the lymph node.

Because histologic types of metastatic deposits in lymph nodes often varied in a patient with Stage III tumor, we found it difficult to determine the predominant type in each case. When examined in each positive node, histologic types of metastatic deposits were not associated with capsular invasion (data not shown).

Microsatellite instability (MSI) status has been known as a prognostic factor in colorectal cancer46,47 and MSI-H status has been reported to correlate with histologic parameters, such as mucinous or medullary histology and Crohn’s-like lymphoid infiltrates, and with right sidedness of the tumor.48,49 Although we did not assess the MSI status of the tumors by use of immunohistochemical or molecular method in the present study, predominant mucinous histology of the main tumor was identified in 11 patients and medullary histology in 2 patients; 41 tumors were located in the right side. These features did not correlate with favorable outcome in our study; moreover, no significant association was observed between these clinicopathologic features and lymph node capsular invasion.

Even the definition of an involved lymph node remains controversial. According to the fifth edition of the UICC/AJCC staging guidelines, a tumor nodule ≥3 mm in diameter in the pericolic or perirectal fat without histologic evidence of residual lymph node is classified as regional lymph node metastasis.11 However, it has been suggested that those nodules often are not derived from destroyed metastatic nodes but are intravascular, perivascular, or perineural extensions of the primary tumor, and represent a feature of poor prognosis, independently of their number and size.25,50,51 Thus, the sixth edition of the UICC/AJCC staging guidelines classified those nodules into two entities: a nodule with a smooth contour is classified in the pN category as a regional lymph node metastasis, whereas a nodule with an irregular contour is classified in the T category coded as V1 or V2 for venous invasion.5,6 In the present study, the authors identified tumor nodules without histologic evidence of residual node in 17 cases (11 percent) from Stage III patients. We, therefore, applied the two different approaches in the analyses according to both guidelines. Fortunately, the results of the two analyses were similar.

A possible limitation of the study is that our study population was relatively small, although it was larger than those of the previous studies by Komuta et al.10 and Heide et al.,23 which might have diluted the significance of conventional prognostic factors leading to accentuate that of lymph node capsular invasion. Furthermore, the favorable outcome of the entire population of Stage III patients in our study (five-year, recurrence-free and cancer-specific survival rates were 72.4 and 73.8 percent, respectively) may have further augmented the effect. It would be of value to further investigate the prognostic significance of lymph node capsular invasion.

In the current study, one experienced surgeon (YS) participated in both the preoperative diagnosis and the operative procedure of all patients. This probably eliminates the variable of surgeon-related prognostic factors noted in previously published multicenter studies. The surgical procedure consisted of standard radical resection in most cases and of limited resection in a few cases.

Patients with TNM Stage III colorectal cancer are a heterogeneous group. Approximately half, without lymph node capsular invasion, have good prognosis similar to that of patients with Stage II disease, whereas the other half, with capsular invasion, have a poor prognosis, indicating the need for adjuvant therapy and intensive follow-up. Surgery and adjuvant chemotherapy are considered the standard treatments for Stage III disease (irrelevant to N-number), which include 5-fluorouracil and leucovorin.52 New drugs, such as irinotecan or oxaliplatin, are coming to be incorporated not only for the advanced stages but also in an adjuvant setting.53 Considering the adverse effects and cost-effectiveness of these drugs as well as the wide spectrum of Stage III disease, better assessment of prognosis in patients with Stage III colorectal cancer could allow individually adapted treatment decisions with the potential of toxicity sparing and therapy intensification.

References

InstitutionalAuthorNameGastrointestinal Tumor Study Group (1984) ArticleTitleAdjuvant therapy of colon cancer–results of a prospectively randomized trial N Engl J Med 310 737–743 Occurrence Handle10.1056/NEJM198403223101201

ER Fisher R Sass A Palekar B Fisher N Wolmark (1989) ArticleTitleDukes’ classification revisited. Findings from the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Projects (Protocol R-01) Cancer 64 2354–2360 Occurrence Handle2804927 Occurrence Handle1:STN:280:DyaK3c%2FjtVWnsw%3D%3D Occurrence Handle10.1002/1097-0142(19891201)64:11<2354::AID-CNCR2820641127>3.0.CO;2-#

R Tang JY Wang JS Chen et al. (1995) ArticleTitleSurvival impact of lymph node metastasis in TNM stage III carcinoma of the colon and rectum J Am Coll Surg 180 705–712 Occurrence Handle7773484 Occurrence Handle1:STN:280:DyaK2M3ptFGnsg%3D%3D

JR Jass SB Love JM Northover (1987) ArticleTitleA new prognostic classification of rectal cancer Lancet 1 1303–1306 Occurrence Handle2884421 Occurrence Handle1:STN:280:DyaL2s3islOiug%3D%3D Occurrence Handle10.1016/S0140-6736(87)90552-6

FL Greene DL Page ID Fleming et al. (2002) AJCC cancer staging manual EditionNumber6 Springer New York

LH Sobin C Wittekind (Eds) (2002) International Union Against Cancer (UICC). TNM classification of malignant tumours EditionNumber6 Wiley New York

M Sasaki H Watanabe JR Jass et al. (1997) ArticleTitleOccult lymph node metastases detected by cytokeratin immunohistochemistry predict recurrence in “node-negative” colorectal cancer J Gastroenterol 32 758–764 Occurrence Handle9430013 Occurrence Handle1:STN:280:DyaK1c%2FptFynug%3D%3D Occurrence Handle10.1007/BF02936951

AE Merrie AM Rij Particlevan ER Dennett LV Phillips K Yun JL McCall (2003) ArticleTitlePrognostic significance of occult metastases in colon cancer Dis Colon Rectum 46 221–231 Occurrence Handle12576896 Occurrence Handle10.1007/s10350-004-6527-z

GJ Liefers AM Cleton-Jansen CJ Velde Particlevan de et al. (1998) ArticleTitleMicrometastases and survival in stage II colorectal cancer N Engl J Med 339 223–228 Occurrence Handle9673300 Occurrence Handle1:STN:280:DyaK1czivVKhuw%3D%3D Occurrence Handle10.1056/NEJM199807233390403

K Komuta S Okudaira M Haraguchi J Furui T Kanematsu (2001) ArticleTitleIdentification of extracapsular invasion of the metastatic lymph nodes as a useful prognostic sign in patients with resectable colorectal cancer Dis Colon Rectum 44 1838–1844 Occurrence Handle11742171 Occurrence Handle1:STN:280:DC%2BD3MjgtV2isQ%3D%3D Occurrence Handle10.1007/BF02234464

LH Sobin C Wittekind (Eds) (1997) International Union Against Cancer (UICC). TNM classification of malignant tumours EditionNumber5 Wiley New York

AM Cohen S Tremiterra F Candela HT Thaler ER Sigurdson (1991) ArticleTitlePrognosis of node-positive colon cancer Cancer 67 1859–1861 Occurrence Handle2004298 Occurrence Handle1:STN:280:DyaK3M7mvVSltw%3D%3D Occurrence Handle10.1002/1097-0142(19910401)67:7<1859::AID-CNCR2820670707>3.0.CO;2-A

C Ratto L Sofo M Ippoliti et al. (1999) ArticleTitleAccurate lymph-node detection in colorectal specimens resected for cancer is of prognostic significance Dis Colon Rectum 42 143–154 Occurrence Handle10211489 Occurrence Handle1:STN:280:DyaK1M3is1Cksw%3D%3D Occurrence Handle10.1007/BF02237119

JH Wong S Steinemann P Tom S Morita P Tauchi-Nishi (2002) ArticleTitleVolume of lymphatic metastases does not independently influence prognosis in colorectal cancer J Clin Oncol 20 1506–1511 Occurrence Handle11896098 Occurrence Handle10.1200/JCO.20.6.1506

NS Goldstein A Mani F Vicini J Ingold (1999) ArticleTitlePrognostic features in patients with stage T1 breast carcinoma and a 0.5-cm or less lymph node metastasis. Significance of lymph node hilar tissue invasion Am J Clin Pathol 111 21–28 Occurrence Handle9894450 Occurrence Handle1:STN:280:DyaK1M7htFyhsw%3D%3D

KB Stitzenberg AA Meyer SL Stern et al. (2003) ArticleTitleExtracapsular extension of the sentinel lymph node metastasis: a predictor of nonsentinel node tumor burden Ann Surg 237 607–612 Occurrence Handle12724626 Occurrence Handle10.1097/00000658-200305000-00002

M Brasilino de Carvalho (1998) ArticleTitleQuantitative analysis of the extent of extracapsular invasion and its prognostic significance: a prospective study of 170 cases of carcinoma of the larynx and hypopharynx Head Neck 20 16–21 Occurrence Handle9464947 Occurrence Handle1:STN:280:DyaK1c7isVGqtg%3D%3D Occurrence Handle10.1002/(SICI)1097-0347(199801)20:1<16::AID-HED3>3.0.CO;2-6

JN Myers JS Greenberg V Mo D Roberts (2001) ArticleTitleExtracapsular spread. A significant predictor of treatment failure in patients with squamous cell carcinoma of the tongue Cancer 92 3030–3036 Occurrence Handle11753980 Occurrence Handle1:STN:280:DC%2BD38%2Fgt1ShsQ%3D%3D Occurrence Handle10.1002/1097-0142(20011215)92:12<3030::AID-CNCR10148>3.0.CO;2-P

H Yamashita S Noguchi N Murakami H Kawamoto S Watanabe (1997) ArticleTitleExtracapsular invasion of lymph node metastasis is an indicator of distant metastasis and poor prognosis in patients with thyroid papillary carcinoma Cancer 80 2268–2272 Occurrence Handle9404704 Occurrence Handle1:STN:280:DyaK1c%2Fmslajug%3D%3D Occurrence Handle10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(19971215)80:12<2268::AID-CNCR8>3.0.CO;2-Q

TL Griebling D Ozkutlu WA See MB Cohen (1997) ArticleTitlePrognostic implications of extracapsular extension of lymph node metastases in prostate cancer Mod Pathol 10 804–809 Occurrence Handle9267823 Occurrence Handle1:STN:280:DyaK2svhtlWrsg%3D%3D

MT Ballo MD Bonnen AS Garden et al. (2003) ArticleTitleAdjuvant irradiation for cervical lymph node metastases from melanoma Cancer 97 1789–1796 Occurrence Handle12655537 Occurrence Handle10.1002/cncr.11243

J Velden Particlevan der AC Lindert Particlevan FB Lammes et al. (1995) ArticleTitleExtracapsular growth of lymph node metastases in squamous cell carcinoma of the vulva. The impact on recurrence and survival Cancer 75 2885–2890 Occurrence Handle7773938 Occurrence Handle10.1002/1097-0142(19950615)75:12<2885::AID-CNCR2820751215>3.0.CO;2-3

J Heide A Krull J Berger (2004) ArticleTitleExtracapsular spread of nodal metastasis as a prognostic factor in rectal cancer Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 58 773–778 Occurrence Handle14967433 Occurrence Handle10.1016/S0360-3016(03)01616-X

T Lerut W Coosemans G Decker et al. (2003) ArticleTitleExtracapsular lymph node involvement is a negative prognostic factor in T3 adenocarcinoma of the distal esophagus and gastroesophageal junction J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 126 1121–1128 Occurrence Handle14566257 Occurrence Handle1:STN:280:DC%2BD3svovFaluw%3D%3D Occurrence Handle10.1016/S0022-5223(03)00941-3

H Ueno H Mochizuki S Tamakuma (1998) ArticleTitlePrognostic significance of extranodal microscopic foci discontinuous with primary lesion in rectal cancer Dis Colon Rectum 41 55–61 Occurrence Handle9510311 Occurrence Handle1:STN:280:DyaK1c7mvFWgsw%3D%3D Occurrence Handle10.1007/BF02236896

NS Goldstein (2002) ArticleTitleLymph node recoveries from 2427 pT3 colorectal resection specimens spanning 45 years: recommendations for a minimum number of recovered lymph nodes based on predictive probabilities Am J Surg Pathol 26 179–189 Occurrence Handle11812939 Occurrence Handle10.1097/00000478-200202000-00004

F Cianchi A Palomba V Boddi et al. (2002) ArticleTitleLymph node recovery from colorectal tumor specimens: recommendation for a minimum number of lymph nodes to be examined World J Surg 26 384–389 Occurrence Handle11865379 Occurrence Handle10.1007/s00268-001-0236-8

FC Wright CH Law LD Last et al. (2004) ArticleTitleBarriers to optimal assessment of lymph nodes in colorectal cancer specimens Am J Clin Pathol 121 663–670 Occurrence Handle15151206 Occurrence Handle10.1309/17VK-M33B-FXF9-T8WD

JH Wong R Severino MB Honnebier P Tom TS Namiki (1999) ArticleTitleNumber of nodes examined and staging accuracy in colorectal carcinoma J Clin Oncol 17 2896–2900 Occurrence Handle10561368 Occurrence Handle1:STN:280:DC%2BD3c%2FjtVSqtQ%3D%3D

S Caplin JP Cerottini FT Bosman MT Constanda JC Givel (1998) ArticleTitleFor patients with Dukes’ B (TNM Stage II) colorectal carcinoma, examination of six or fewer lymph nodes is related to poor prognosis Cancer 83 666–672 Occurrence Handle9708929 Occurrence Handle1:STN:280:DyaK1cznt1Klsg%3D%3D Occurrence Handle10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(19980815)83:4<666::AID-CNCR6>3.0.CO;2-I

G Cserni (1999) ArticleTitleLymph node harvest reporting in patients with carcinoma of the large bowel: a French population-based study Cancer 85 243–245 Occurrence Handle9922000 Occurrence Handle1:STN:280:DyaK1M7hvV2ksQ%3D%3D Occurrence Handle10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(19990101)85:1<243::AID-CNCR35>3.0.CO;2-L

H Nelson N Petrelli A Carlin et al. (2001) ArticleTitleGuidelines 2000 for colon and rectal cancer surgery J Natl Cancer Inst 93 583–596 Occurrence Handle11309435 Occurrence Handle1:STN:280:DC%2BD3M3hvFejtg%3D%3D Occurrence Handle10.1093/jnci/93.8.583

L Herrera JR Villarreal (1992) ArticleTitleIncidence of metastases from rectal adenocarcinoma in small lymph nodes detected by a clearing technique Dis Colon Rectum 35 783–788 Occurrence Handle1644003 Occurrence Handle1:STN:280:DyaK38zlsVCqtg%3D%3D Occurrence Handle10.1007/BF02050329

J Hida M Yasutomi K Fujimoto et al. (1996) ArticleTitleAnalysis of regional lymph node metastases from rectal carcinoma by the clearing method. Justification of the use of sigmoid in J-pouch construction after low anterior resection Dis Colon Rectum 39 1282–1285 Occurrence Handle8918439 Occurrence Handle1:STN:280:DyaK2s%2Fns1WhsA%3D%3D Occurrence Handle10.1007/BF02055123

S Noura H Yamamoto Y Miyake et al. (2002) ArticleTitleImmunohistochemical assessment of localization and frequency of micrometastases in lymph nodes of colorectal cancer Clin Cancer Res 8 759–767 Occurrence Handle11895906

J Mulsow DC Winter JC O’Keane PR O’Connell (2003) ArticleTitleSentinel lymph node mapping in colorectal cancer Br J Surg 90 659–667 Occurrence Handle12808612 Occurrence Handle1:STN:280:DC%2BD3s3otVCktQ%3D%3D Occurrence Handle10.1002/bjs.4217

MR Kell DC Winter GC O’Sullivan F Shanahan HP Redmond (2000) ArticleTitleBiological behaviour and clinical implications of micrometastases Br J Surg 87 1629–1639 Occurrence Handle11122176 Occurrence Handle1:STN:280:DC%2BD3M%2FnvFersw%3D%3D Occurrence Handle10.1046/j.1365-2168.2000.01606.x

R Broll V Schauer H Schimmelpenning et al. (1997) ArticleTitlePrognostic relevance of occult tumor cells in lymph nodes of colorectal carcinomas: an immunohistochemical study Dis Colon Rectum 40 1465–1471 Occurrence Handle9407986 Occurrence Handle1:STN:280:DyaK1c%2FmvFyktw%3D%3D Occurrence Handle10.1007/BF02070713

JK Greenson CE Isenhart R Rice C Mojzisik D Houchens EW Martin SuffixJr (1994) ArticleTitleIdentification of occult micrometastases in pericolic lymph nodes of Duke’s B colorectal cancer patients using monoclonal antibodies against cytokeratin and CC49. Correlation with long-term survival Cancer 73 563–569 Occurrence Handle7507795 Occurrence Handle1:STN:280:DyaK2c7jtVahtA%3D%3D Occurrence Handle10.1002/1097-0142(19940201)73:3<563::AID-CNCR2820730311>3.0.CO;2-D

N Hayashi H Arakawa H Nagase et al. (1994) ArticleTitleGenetic diagnosis identifies occult lymph node metastases undetectable by the histopathological method Cancer Res 54 3853–3856 Occurrence Handle8033106 Occurrence Handle1:CAS:528:DyaK2cXlt1Kht7c%3D

MD Jeffers GM O’Dowd H Mulcahy M Stagg DP O’Donoghue M Toner (1994) ArticleTitleThe prognostic significance of immunohistochemically detected lymph node micrometastases in colorectal carcinoma J Pathol 172 183–187 Occurrence Handle7513353 Occurrence Handle1:STN:280:DyaK2c3itlCmsg%3D%3D Occurrence Handle10.1002/path.1711720205

J Tschmelitsch DS Klimstra AM Cohen (2000) ArticleTitleLymph node micrometastases do not predict relapse in stage II colon cancer Ann Surg Oncol 7 601–608 Occurrence Handle11005559 Occurrence Handle1:STN:280:DC%2BD3cvltVGktw%3D%3D

KW Scott RH Grace (1989) ArticleTitleDetection of lymph node metastases in colorectal carcinoma before and after fat clearance Br J Surg 76 1165–1167 Occurrence Handle2688803 Occurrence Handle1:STN:280:DyaK3c%2FovF2msQ%3D%3D

I Carr (1983) ArticleTitleLymphatic metastasis Cancer Metastasis Rev 2 307–317 Occurrence Handle6367969 Occurrence Handle1:STN:280:DyaL2c7ls1amsQ%3D%3D Occurrence Handle10.1007/BF00048483

P Brodt (1991) ArticleTitleAdhesion mechanisms in lymphatic metastasis Cancer Metastasis Rev 10 23–32 Occurrence Handle1914072 Occurrence Handle1:CAS:528:DyaK3sXmsVKku7c%3D Occurrence Handle10.1007/BF00046841

MR Kohonen-Corish JJ Daniel C Chan et al. (2005) ArticleTitleLow microsatellite instability is associated with poor prognosis in stage C colon cancer J Clin Oncol 23 2318–2324 Occurrence Handle15800322 Occurrence Handle1:CAS:528:DC%2BD2MXjsVyhsrw%3D Occurrence Handle10.1200/JCO.2005.00.109

CM Wright OF Dent RC Newland et al. (2005) ArticleTitleLow level microsatellite instability may be associated with reduced cancer specific survival in sporadic stage C colorectal carcinoma Gut 54 103–108 Occurrence Handle15591513 Occurrence Handle1:CAS:528:DC%2BD2MXntFOqtw%3D%3D Occurrence Handle10.1136/gut.2003.034579

A Buckowitz HP Knaebel A Benner et al. (2005) ArticleTitleMicrosatellite instability in colorectal cancer is associated with local lymphocyte infiltration and low frequency of distant metastases Br J Cancer 92 1746–1753 Occurrence Handle15856045 Occurrence Handle1:CAS:528:DC%2BD2MXjvVansLc%3D Occurrence Handle10.1038/sj.bjc.6602534

R Ward A Meagher I Tomlinson et al. (2001) ArticleTitleMicrosatellite instability and the clinicopathological features of sporadic colorectal cancer Gut 48 821–829 Occurrence Handle11358903 Occurrence Handle1:STN:280:DC%2BD3M3msl2isA%3D%3D Occurrence Handle10.1136/gut.48.6.821

A Prabhudesai S Arif CJ Finlayson D Kumar (2003) ArticleTitleImpact of microscopic extranodal tumor deposits on the outcome of patients with rectal cancer Dis Colon Rectum 46 1531–1537 Occurrence Handle14605575 Occurrence Handle10.1007/s10350-004-6809-5

NS Goldstein JR Turner (2000) ArticleTitlePericolonic tumor deposits in patients with T3N+MO colon adenocarcinomas: markers of reduced disease free survival and intra-abdominal metastases and their implications for TNM classification Cancer 88 2228–2238 Occurrence Handle10820343 Occurrence Handle1:STN:280:DC%2BD3c3otlSgtw%3D%3D Occurrence Handle10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(20000515)88:10<2228::AID-CNCR5>3.0.CO;2-1

N Wolmark H Rockette E Mamounas et al. (1999) ArticleTitleClinical trial to assess the relative efficacy of fluorouracil and leucovorin, fluorouracil and levamisole, and fluorouracil, leucovorin, and levamisole in patients with Dukes’ B and C carcinoma of the colon: results from National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project C-04 J Clin Oncol 17 3553–3559 Occurrence Handle10550154 Occurrence Handle1:CAS:528:DyaK1MXnvVGltLo%3D

T Andre C Boni L Mounedji-Boudiaf et al. (2004) ArticleTitleOxaliplatin, fluorouracil, and leucovorin as adjuvant treatment for colon cancer N Engl J Med 350 2343–2351 Occurrence Handle15175436 Occurrence Handle1:CAS:528:DC%2BD2cXks1Gjt78%3D Occurrence Handle10.1056/NEJMoa032709

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Nelson H. Tsuno, M.D., Ph.D., Department of Transfusion Medicine, University of Tokyo, Naomi Uemura, M.D., Ph.D., Department of Gastroenterology, International Medical Center of Japan, and Takuro Sasaki, Varie Co. Ltd. for assistance.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Read in part at the meeting of The International Society of University Colon and Rectal Surgeons, Budapest, Hungary, June 9, 2004.

Reprints are not available.

About this article

Cite this article

Yano, H., Saito, Y., Kirihara, Y. et al. Tumor Invasion of Lymph Node Capsules in Patients with Dukes C Colorectal Adenocarcinoma. Dis Colon Rectum 49, 1867–1877 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10350-006-0733-9

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10350-006-0733-9