Abstract

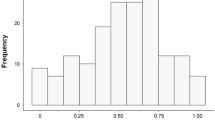

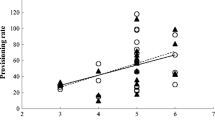

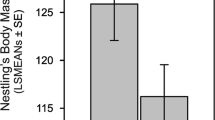

Post-fledging care constitutes a large proportion of the total costs of parental care in many bird species. Despite being recognized as of critical importance to the survival of the offspring and their recruitment into the breeding population, post-fledging care, including the relative contribution by male and female parents, is under-studied. In this study, we quantified food provisioning (prey deliveries) by male and female Tengmalm’s Owl (Aegolius funereus) parents to their offspring both in the nestling and the post-fledging stages, in years of differing natural prey abundance. Parents and at least one offspring in 26 families were fitted with radio-transmitters. Male parents exhibited higher delivery rates than did females throughout the late nestling and post-fledging stages, but the intersexual difference was smaller in broods that were not deserted by the female at any stage. The female deserted her mate and offspring at some stage in 63% of the broods. Overall, deserted males delivered more prey to their offspring than did non-deserted males. Delivery rates were generally higher post-fledging. Prey delivery rates differed among years, and were highest in low vole years (probably because of smaller prey items), intermediate in peak vole years, and lowest in years of vole increase. Prey delivery rates increased with increasing brood size for both sexes, but the response was stronger in females. We suggest that female Tengmalm’s Owls contribute less than males because they are in a position to decide on their level of provisioning effort first, and because of the potential for re-mating after deserting the first brood.

Zusammenfassung

Geschlechterrollen bei der Fürsorge für Flügglinge: Weibliche Raufußkäuze tragen wenig zur Futterversorgung bei

Die Fürsorge für Flügglinge macht bei vielen Vogelarten einen großen Anteil der Gesamtkosten der Brutpflege aus. Obwohl bekannt ist, dass die Fürsorge für Flügglinge von entscheidender Bedeutung für das Überleben der Nachkommen und ihre Rekrutierung in die Brutpopulation ist, ist dieser Aspekt der Brutpflege, einschließlich des relativen Beitrags von Männchen und Weibchen, nicht gut untersucht. In dieser Studie haben wir in Jahren mit unterschiedlicher natürlicher Beuteabundanz quantifiziert, wie männliche und weibliche Raufußkäuze (Aegolius funereus) ihre Nachkommen mit Futter versorgten, sowohl im Nestlingsstadium als auch nach dem Ausfliegen. Die Elternvögel und mindestens ein Jungvogel aus 26 Familien wurden mit Radiosendern ausgestattet. Männchen wiesen während des späten Nestlingsstadiums und nach dem Ausfliegen höhere Fütterraten auf als Weibchen, aber der Unterschied zwischen den Geschlechtern war geringer in Bruten, die nicht zu irgendeinem Zeitpunkt vom Weibchen verlassen wurden. Das Weibchen verließ irgendwann seinen Partner und seine Nachkommen in 63% der Bruten. Insgesamt brachten verlassene Männchen ihren Nachkommen mehr Beute als nicht verlassene. Die Fütterraten waren nach dem Ausfliegen generell höher. Sie unterschieden sich zwischen den Jahren und waren am höchsten in Jahren mit geringer Wühlmausabundanz (wahrscheinlich aufgrund kleinerer Beutestücke), mittel in Jahren mit höchster Wühlmausabundanz und niedrig in Jahren mit zunehmender Wühlmausabundanz. Die Fütterraten nahmen mit ansteigender Brutgröße für beide Geschlechter zu, doch die Antwort war bei Weibchen stärker ausgeprägt. Wir schlagen vor, dass weibliche Raufußkäuze einen geringeren Beitrag leisten als Männchen, da sie in der Lage sind, über das Ausmaß ihres Fütterungsaufwands zuerst zu entscheiden, und für sie die Möglichkeit besteht, sich nach Verlassen der ersten Brut wieder zu verpaaren.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Anderson DR, Link WA, Johnson DH, Burnham KP (2001) Suggestions for presenting the results of data analyses. J Wildl Manag 65:373–378

Andersson M, Norberg RÅ (1981) Evolution of reversed sexual size dimorphism and role partitioning among predatory birds, with a size scaling of flight performance. Biol J Linn Soc 15:105–130

Arroyo BE, DeCornulier Th, Bretagnolle V (2002) Parental investment and parent-offspring conflicts during the postfledging period in Montagu’s harriers. Anim Behav 63:235–244

Bjørnstad ON, Ims RA, Lambin X (1999) Spatial population dynamics: analyzing patterns and processes of population synchrony. Trends Ecol Evol 14:427–432

Bolker BM, Brooks ME, Clark CJ, Geange SW, Poulsen JR, Stevens MHH, White J-SS (2008) Generalized linear mixed models: a practical guide for ecology and evolution. Trends Ecol Evol 24:127–135

Bustamante J (1994) Behavior of colonial Common Kestrels (Falco tinnunculus) during the post-fledging dependence period in southwestern Spain. J Raptor Res 28:79–83

Bustamante J, Negro JJ (1994) The post-fledging dependence period of the lesser kestrel (Falco naumanni) in southwestern Spain. J Raptor Res 28:158–163

Carlsson B-G, Hörnfeldt B (1994) Determination of nestling age and laying date in Tengmalm’s Owl: use of wing length and body mass. Condor 96:555–559

Clutton-Brock TH (1991) The evolution of parental care. Princeton University Press, Princeton

Cockburn A (2006) Prevalence of different modes of parental care in birds. Proc R Soc Lond B 273:1375–1383

Collopy MW (1984) Parental care and feeding ecology of Golden Eagle nestlings. Auk 101:753–760

Cramp S (1985) The birds of the western palearctic, vol IV. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Dawson RD, Bortolotti GR (2002) Experimental evidence for food limitation and sex-specific strategies of American kestrels (Falco sparverius) provisioning offspring. Behav Ecol Sociobiol 52:43–52

Eldegard K, Sonerud GA (2009) Female offspring desertion and male-only care increase with natural and experimental increase in food abundance. Proc R Soc Lond B 276:1713–1721

Eldegard K, Sonerud GA (2010) Experimental increase in food supply influences the outcome of within-family conflicts in Tengmalm’s owl. Behav Ecol 64:815–826

Eldegard K, Selås V, Sonerud GA, Steel C, Rafoss T (2003) The effect of parent sex on prey deliveries to fledgling Eurasian sparrowhawks Accipiter nisus. Ibis 145:667–672

Grüebler MU, Naef-Daenzer B (2010) Survival benefits of post-fledging care: experimental approach to a critical part of avian reproductive strategies. J Anim Ecol 79:334–341

Guo H, Cao L, Peng L, Zhao G, Tang S (2010) Parental care, development of foraging skills, and transition to independence in the red-footed booby. Condor 112:38–47

Hakkarainen H, Korpimäki E (1995) Contrasting phenotypic correlations in food provision of male Tengmalm’s owls (Aegolius funereus) in a temporally heterogenous environment. Evol Ecol 9:30–37

Harding AMA, van Pelt TI, Lifjeld JT, Mehlum F (2004) Sex differences in little auk Alle alle parental care: transition from biparental to paternal-only care. Ibis 146:642–651

Hinde CA (2006) Negotiation over offspring care?—a positive response to partner-provisioning rate in great tits. Behav Ecol 17:6–12

Hinde CA, Kilner RM (2007) Negotiations within the family over the supply of parental care. Proc R Soc Lond B 274:53–60

Hipkiss T (2002) Sexual size dimorphism in Tengmalm’s owl (Aegolius funereus) on autumn migration. J Zool 257:281–285

Hörnfeldt B, Carlsson B-G, Löfgren O, Eklund U (1990) Effects of cyclic food supply on breeding performance in Tengmalm’s owl (Aegolius funereus). Can J Zool 68:522–530

Johnstone RA, Hinde CA (2006) Negotiation over offspring care–how should parents respond to each other’s efforts? Behav Ecol 17:818–827

Kokko H, Jennions MD (2008) Parental investment, sexual selection and sex ratios. J Evol Biol 21:919–948

Korpimäki E (1981) On the ecology and biology of Tengmalm’s owl (Aegolius funereus) in Southern Ostrobothnia and Suomenselkä, western Finland. Acta Univ Oulu Ser A Bio 13:1–84

Korpimäki E (1987) Clutch size, breeding success and brood size experiments in Tengmalm’s owl Aegolius funereus: a test of hypotheses. Ornis Scand 18:277–284

Korpimäki E (1988) Diet of breeding Tengmalm’s owls Aegolius funereus: long term changes and year-to-year variation under cyclic food conditions. Ornis Fenn 65:21–30

Korpimäki E (1990) Body mass of breeding Tengmalm’s owls Aegolius funereus: seasonal, between-year, site and age-related variation. Ornis Scand 21:169–178

Korpimäki E, Lagerström M (1988) Survival and natal dispersal of fledglings of Tengmalm’s owl in relation to fluctuating food conditions and hatching date. J Anim Ecol 57:433–441

Korpimäki E, Salo P, Valkama J (2011) Sequential polyandry and brood desertion increases female fitness in a bird with obligatory bi-parental care. Behav Ecol Sociobiol 65:1093–1102

Kosztolányi A, Cuthill IC, Székely T (2008) Negotiation between parents over care: reversible compensation during incubation. Behav Ecol 20:446–452

Krüger O (2005) The evolution of reversed sexual size dimorphism in hawks, falcons and owls: a comparative study. Evol Ecol 19:467–486

Lessells CM, Parker GA (1999) Parent-offspring conflict: the full-sib half-sib fallacy. Proc R Soc Lond B 266:1637–1643

Masman D, Daan S, Dijkstra C (1988) Time allocation in the kestrel (Falco tinnunculus), and the principle of energy minimization. J Anim Ecol 57:411–432

Massemin S, Korpimäki E, Wiehn J (2000) Reversed sexual size dimorphism in raptors: evaluation of the hypotheses in kestrels breeding in a temporally changing environment. Oecologia 124:26–32

Middleton HA, Green DJ, Krebs EA (2007) Fledgling begging and parental responsiveness in American dippers (Cinclus mexicanus). Behaviour 144:485–501

Mikkola H (1983) Owls of Europe. Poyser, Calton

Naef-Daenzer L, Grüebler MU, Naef-Daenzer B (2011) Parental care trade-offs in the inter-brood phase in barn swallows Hirundo rustica. Ibis 153:27–36

Newton I (1979) Population ecology of raptors. Poyser, Berkhamsted

Newton I (1986) The sparrowhawk. Poyser, Calton

Olson VA, Liker A, Freckleton RP, Székely T (2008) Parental conflict in birds: comparative analyses of offspring development, ecology and mating opportunities. Proc R Soc Lond B 275:301–307

Penteriani V, Delgado MM, Maggio C, Aradis A, Sergio F (2005) Development of chicks and predispersal behavior of young in the eagle owl Bubo bubo. Ibis 147:155–168

Real J, Mañosa S, Codina J (1998) Post-nestling dependence period in the Bonelli’s eagle Hieraaetus fasciatus. Ornis Fenn 75:129–137

Rogers AC, Mulder RA (2004) Breeding ecology and social behaviour of an antiphonal duetter, the eastern whipbird (Psophodes olivaceus). Aust J Zool 52:417–435

Roulin A, Bersier L-F (2007) Nestling barn owls beg more intensely in the presence of their mother than in the presence of their father. Anim Behav 74:1099–1106

Roulin A, Ducrest A-L, Dijkstra C (1999) Effect of brood size manipulations on parents and offspring in the barn owl Tyto alba. Ardea 87:91–100

Selås V, Sonerud GA, Histøl T, Hjeljord O (2001) Synchrony in short-term fluctuations of body mass of moose calves and population density of bank voles supports the mast depression hypothesis. Oikos 92:271–278

Slagsvold T, Sonerud GA (2007) Prey size and ingestion rate in raptors: importance for sex roles and reversed sexual size dimorphism. J Avian Biol 38:650–661

Sonerud GA (1985) Nest hole shift in Tengmalm’s owl Aegolius funereus as defence against nest predation involving log-term memory in the predator. J Anim Ecol 54:179–192

Sonerud GA (1986) Effect of snow cover on seasonal changes in diet, habitat, and regional distribution of raptors that prey on small mammals in boreal zones of Fennoscandia. Holarctic Ecol 9:33–47

Sonerud GA (1988) What causes extended lows in microtine cycles? Analysis of fluctuations in sympatric shrew and microtine populations in Fennoscandia. Oecologia 76:37–42

Stearns SC (1992) The evolution of life histories. Oxford University Press, New York

Steen H, Ims RA, Sonerud GA (1996) Spatial and temporal patterns of small-rodent population dynamics at a regional scale. Ecology 77:2365–2372

Sunde P (2008) Parent-offspring conflict over duration of parental care and its consequences in tawny owls Strix aluco. J Avian Biol 39:242–246

Sunde P, Markussen BEN (2005) Using counts of begging young to estimate post-fledging survival in tawny owls Strix aluco. Bird Study 52:343–345

Sunde P, Bølstad MS, Møller JD (2003) Reversed sexual dimorphism in tawny owls, Strix aluco, correlates with duty division in breeding effort. Oikos 101:265–278

Székely T, Webb JN, Houston AI, McNamara JM (1996) An evolutionary approach to offspring desertion in birds. In: Nolan V, Ketterson ED (eds) Current ornithology. Plenum, New York, vol 13, pp 271–330

Tarwater CE, Brawn JD (2010) The post-fledging period in a tropical bird: patterns of parental care and survival. J Avian Biol 41:479–487

Temeles EJ (1985) Sexual size dimorphism of bird-eating hawks: the effect of prey vulnerability. Am Nat 125:485–499

Trivers RL (1972) Parental investment and sexual selection. In: Campbell B (ed) Sexual selection and the descent of man, 1871–1971. Aldine Atherton, Chicago, pp 136–179

Vega LB, Holloway GJ, Millett JE, Richardson DS (2007) Extreme gender-based post-fledging brood division in the toc–toc. Behav Ecol 18:730–735

Vekasy MS, Marzluff JM, Kochert MN, Lehman RN, Steenhof K (1996) Influence of radio transmitters on prairie falcons. J Field Ornithol 67:680–690

Vergara P, Fargallo JA (2008) Sex, melanic coloration, and sibling competition during the postfledging dependence period. Behav Ecol 19:847–853

Vergara P, Fargallo J, Martínez-Padilla J (2010) Reaching independence: food supply, parent quality, and offspring phenotypic characters in kestrels. Behav Ecol 21:507–512

Verhulst S, Hut RA (1996) Post-fledging care, multiple breeding and the costs of reproduction in the great tit. Anim Behav 51:957–966

Wells KMS, Harvey HT, White JD et al (2007) A review of the avian post-fledging literature: major themes and future recommendations. COS 4-2 contributed oral abstract. In: COS4—conservation ecology and ecosystem management: planning and policy. Ecological Society of America/Society for Ecological Restoration International, Joint Meeting August 2007

Wiehn J, Korpimäki E (1997) Food limitation on brood size: experimental evidence in the Eurasian kestrel. Ecology 78:2043–2050

Wiens JD, Noon BR, Reynolds RT (2006) Post-fledging survival of northern goshawks: the importance of prey abundance, weather, and dispersal. Ecol Appl 16:406–418

Ydenberg RC (2007) Provisioning. In: Stephens DW, Brown JS, Ydenberg RC (eds) Foraging: behaviour and ecology. University of Chicago Press, Chicago, pp 273–303

Ydenberg RC, Forbes LS (1991) The survival-reproduction selection equilibrium and reversed size dimorphism in raptors. Oikos 60:115–120

Acknowledgments

We thank O. Heie, E.J. Hildrum, I. Løvdal, and H. Vognild for assistance in the field; R. Bjørnstad, G. Nyhus, the late F. Rønning, K. Skjærvik, O. Skjærvik, T. Wernberg, and E. Østby for finding some of the owl nests; and H. Antonsen, G. Fry, V. Selås, P. Sunde, J. O. Vik and three anonymous reviewers for comments on previous drafts of the manuscript. The Directorate for Nature Management and the National Animal Research Authority in Norway granted permission to trap and radio-tag the owls, and the Directorate for Nature Management granted permission to trap small mammals. The Research Council of Norway (grant no. 123604/410) and the Nansen Endowment (grants no. 75/96 and 81/97) provided financial support for the study.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical standards

This study complies with Norwegian law; trapping, handling, radio-tagging and follow-up of radio-tagged individuals were done with permission from, and in accordance with, the ethical standards provided by, the Directorate for Nature Management and the National Animal Research Authority of Norway. An ethical note is given in Online Resource 1.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Communicated by T. Friedl.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Appendices

Appendix 1

See Table 3.

Appendix 2

See Table 4.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Eldegard, K., Sonerud, G.A. Sex roles during post-fledging care in birds: female Tengmalm’s Owls contribute little to food provisioning. J Ornithol 153, 385–398 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10336-011-0753-7

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10336-011-0753-7