Abstract

Background

Only partial cross-resistance between docetaxel and paclitaxel has been demonstrated in breast and ovarian cancers. Whether weekly paclitaxel is effective in patients with advanced gastric cancer refractory to docetaxel-based chemotherapy remains unclear, and we aimed to clarify the efficacy and safety of weekly paclitaxel in such patients.

Methods

Patients who had received docetaxel-based regimens were assigned to the prior-docetaxel group, and those who had never received docetaxel were designated as the non-docetaxel group. Paclitaxel at 80 mg/m2 was administered by intravenous infusion in all patients, and this was repeated weekly for 3 weeks out of 4.

Results

Between April 2006 and June 2011, 65 patients were studied: 26 in the prior-docetaxel group and 39 patients were non-docetaxel group. The median age, gender, performance status, histological type, history of gastrectomy, and the locations and numbers of metastatic sites did not differ significantly between the two groups. In the prior-docetaxel group, the response rate (RR) was 14.2% (3/21) among patients with measurable lesions, median progression-free survival (PFS) was 79 days [95% confidence interval (CI), 47–135 days], and overall survival (OS) was 123 days (95% CI, 90–215 days) from the initiation of paclitaxel treatment. In the non-docetaxel group, the RR was 11.5% (3/26) among patients with measurable lesions, PFS was 82 days (95% CI, 52–106 days), and OS was 143 days (95% CI, 121–178 days). The efficacy of weekly paclitaxel thus appeared to be similar in the two groups.

Conclusions

Weekly paclitaxel was modestly active in patients with gastric cancer refractory to docetaxel-based chemotherapy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Recent epidemiologic studies estimate that about 0.9 million cases of gastric cancer are diagnosed annually worldwide. In more than half of all cases, the disease is advanced at the time of diagnosis [1, 2]. Systemic chemotherapy is thus essential for the management of advanced gastric cancer, especially in patients with good performance status (PS). Several chemotherapeutic regimens have been established as first-line therapy, contributing to improved survival [3]. After first-line therapy, 30–70% of patients receive second-line chemotherapy. The proportion of patients who receive second-line chemotherapy is particularly high in Japan [4–7], although its clinical benefits remain unclear.

The taxanes paclitaxel and docetaxel are microtubule-stabilizing agents that induce cell-cycle arrest at the G2/M2 stage. Both of these agents have been used to treat advanced gastric cancer. The phase III V325 study showed that adding docetaxel to cisplatin plus 5-fluorouracil improved the response rate (RR) and overall survival (OS), establishing docetaxel as an effective drug for first-line therapy [8]. Phase II studies of paclitaxel monotherapy reported an RR of 17–28% for second-line as well as first-line therapy [9–12]. Phase II studies of weekly paclitaxel, found to be effective and feasible in several types of cancer, reported an RR of 16% for second-line therapy in advanced gastric cancer [13, 14]. A recent retrospective study of weekly paclitaxel showed similar efficacy even in third-line therapy [15]. Weekly paclitaxel is therefore often used after the failure of first-line therapy. To our knowledge, however, the efficacy of weekly paclitaxel has not been reported in patients with gastric cancer who had previously received docetaxel-based regimens.

In vitro and in vivo analyses have indicated only partial cross-resistance between docetaxel and paclitaxel, although these drugs have similar mechanisms of action [16, 17]. Phase II and III studies showed that patients with metastatic breast cancer previously treated with docetaxel responded to paclitaxel given as a 96-h infusion, suggesting that paclitaxel might be effective for breast cancer resistant to docetaxel [13, 18]. Partial cross-resistance between docetaxel and paclitaxel has also been reported in ovarian cancer and prostate cancer [19, 20].

In this study, we aimed to clarify the efficacy and safety of weekly paclitaxel in patients with advanced gastric cancer refractory to docetaxel-based chemotherapy.

Subjects

We studied patients with unresectable or recurrent gastric cancer who received weekly paclitaxel at two institutions. All subjects fulfilled the following criteria: (1) a histologically confirmed diagnosis of adenocarcinoma of the stomach; (2) treatment with paclitaxel as second- or third-line therapy; (3) refractory to prior chemotherapy; (4) a performance status of 0–2 on the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group scale; (5) adequate bone marrow, renal, and hepatic functions (an absolute neutrophil count of ≥1500/μL, a hemoglobin level of ≥8.0 g/dL, a serum creatinine level of ≤1.5 g/dL, and a serum bilirubin level of ≤1.5 g/dL); (6) no synchronous double cancer or other serious disease. The presence of measurable lesions was not mandatory.

We divided the patients into two groups: patients who had received docetaxel-based regimens were designated as the prior-docetaxel group, and those who had never received docetaxel were designated as the non-docetaxel group. In the prior-docetaxel group, all patients were refractory to docetaxel-based chemotherapy.

Treatment

Paclitaxel at 80 mg/m2 in 250 ml normal saline was administered by intravenous infusion over 1 h, and this was repeated weekly for 3 weeks out of 4. Short-term premedication with dexamethasone 8 mg and ranitidine 50 mg was administered to prevent paclitaxel-induced hypersensitivity reactions. Treatment was repeated until disease progression, the occurrence of unacceptable toxicity, or the patient’s refusal to continue therapy.

Response and toxicity evaluation

We obtained all clinical data retrospectively from the patients’ medical records. Response was assessed on computed tomography (CT) scans every 2 months. Objective responses of measurable lesions were evaluated according to the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST 1.0), and the response was confirmed by CT scans. Patients without measurable lesions were excluded from the analysis of RR. Symptomatic toxicity and laboratory data were monitored every week at the outpatient clinic. Toxicity was evaluated according to the Common Toxicity Criteria for Adverse Events, version 3.0 (CTCAE 3.0).

Statistical analysis

Progression-free survival (PFS) was measured from the day of starting treatment with paclitaxel to the day on which disease progression was confirmed or the final day of follow-up without disease progression. OS was measured from the first day of treatment with paclitaxel until the day of death or the final day of follow-up. Median PFS and OS were estimated by the Kaplan–Meier method.

The two groups were compared with the use of the unpaired χ2 test or Student’s t-test. Correlations between the response to paclitaxel and the cumulative dose of docetaxel were analyzed using Pearson’s correlation coefficient. All statistical analyses were performed with using JMP version 9 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA), and P values of <0.05 (two-sided) were considered to indicate statistical significance.

Results

Patient characteristics

A total of 77 patients with unresectable or recurrent gastric cancer received weekly paclitaxel as second- or third-line therapy between April 2006 and June 2011. Twelve patients were excluded for the following reasons: eight patients had poor performance status, two had hepatic dysfunction, and two had renal dysfunction. Data on the remaining 65 patients were included in the analysis: 26 patients belonged to the prior-docetaxel group, and 39 belonged to the non-docetaxel group.

The patients’ characteristics just before starting weekly paclitaxel are summarized in Table 1. The mean age, gender, performance status, histological type, history of gastrectomy, location of metastases, and the number of metastatic sites did not differ significantly between the two groups. In the prior-docetaxel group, 19 patients had received two regimens, and seven patients with peritoneal dissemination had received one regimen before the weekly paclitaxel. The proportion of patients who received weekly paclitaxel as third-line therapy was greater than that in the non-docetaxel group (P = 0.03). In the first-line chemotherapy in the prior-docetaxel group, 18 patients had received cisplatin (40 mg/m2 on day 1), docetaxel (40 mg/m2 on day 22), and S-1 (80 mg/m2 on days 1–14 and days 22–35) every 6 weeks, and eight had received docetaxel (40 mg/m2 on day 1) and S-1 (80 mg/m2 on days 1–14) every 3 weeks. The median cumulative dose of docetaxel was 220 mg/patient (range 50–715). In the first-line chemotherapy in the non-docetaxel group, 17 patients had received cisplatin (60 mg/m2 on day 1) and S-1 (80 mg/m2 on days 1–21) every 5 weeks, 13 had received S-1 monotherapy (80 mg/m2 on days 1–28) every 6 weeks, and nine had received other regimens.

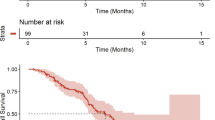

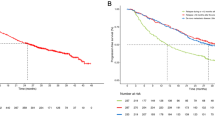

Response and survival

The responses to weekly paclitaxel are shown in Table 2. In all patients with measurable lesions, the RR and the disease control rate (DCR) for weekly paclitaxel were 12.8% (6/47) and 57.4% (27/47), respectively. The RR and DCR were, respectively, 14.2% (3/21) and 47.6% (10/21) in the prior-docetaxel group and 11.5% (3/26) and 65.3% (17/26) in the non-docetaxel group. The RR and DCR were similar in the two groups. In the study group as a whole, the median PFS was 79 days [95% confidence interval (CI), 56–106 days], and the median OS was 136 days (95% CI, 121–176 days). In the prior-docetaxel group and non-docetaxel group, the median PFS values were 79 days (95% CI, 47–135 days) and 82 days (95% CI, 52–106 days), and the median OS values were 123 days (95% CI, 90–215 days) and 143 days (95% CI, 121–178 days), respectively (Figs. 1, 2). The efficacy of weekly paclitaxel for second- or third-line therapy thus appeared to be similar regardless of whether or not docetaxel had been included in the first-line therapy. There was no correlation between the cumulative dose of docetaxel and the response to paclitaxel in the prior-docetaxel group (Fig. 3; r 2 = 0.013).

Adverse events

The hematological and non-hematological toxicities are shown in Table 3. Hematological toxicities were relatively common. The incidences of grade 3 or 4 leukopenia and neutropenia were, respectively, 19 and 8% in the prior-docetaxel group, as compared with 23 and 11% in the non-docetaxel group. Anemia was the most common adverse event, because 55 of the 65 patients had had anemia before the initiation of paclitaxel. No patient in either group had grade 3 or 4 thrombocytopenia. As for the non-hematological toxicities, anorexia and nausea were common. The incidences of grade 3 anorexia and nausea were, respectively, 15 and 4% in the prior-docetaxel group and 11 and 8% in the non-docetaxel group. The incidences of grade 3 fatigue and diarrhea were, respectively, 4 and 0% in the prior-docetaxel group and 0 and 5% in the non-docetaxel group. No patient had grade 3 or 4 vomiting, mucositis, sensory neuropathy, motor neuropathy, edema, or allergic reactions. The proportions of patients with hematological and non-hematological toxicities were similar in the two groups.

Discussion

The present retrospective study evaluated the efficacy and safety of weekly paclitaxel in patients with advanced gastric cancer who had received docetaxel-based chemotherapy. In the prior-docetaxel group, the RR was 12.8%, the median PFS was 79 days, and the median OS was 123 days. Our results showed that weekly paclitaxel was modestly active even in patients with gastric cancer refractory to docetaxel-based chemotherapy, as reported previously in other cancers [17, 18, 20, 21].

Our results are supported by preclinical and clinical evidence. Although docetaxel and paclitaxel share major parts of their structures and mechanisms of action, relative differences may play a role in partial cross-resistance. For example, docetaxel and paclitaxel have different affinities for tubulin-binding sites, different microtubule polymerization patterns, different intracellular retention times and concentrations in target cells, and different potencies for the induction of bcl-2 phosphorylation and apoptosis [16, 17]. The results of preclinical analysis of partial cross-resistance are supported by the findings of clinical studies in several cancers. In phase II trials, weekly paclitaxel after disease progression in women with breast cancer who had previously received docetaxel produced an RR of 17–32% [22–24]. On the other hand, docetaxel was found to be active in small trials of patients with paclitaxel-refractory breast cancer [18, 21].

However, it is difficult to draw firm conclusions from our results with respect to partial cross-resistance between the two drugs, because all the patients in our prior-docetaxel group had received docetaxel-based combined chemotherapy, not monotherapy. In a Japanese phase II trial, patients received docetaxel monotherapy at 60 mg/m2 every 3–4 weeks [25]. In a phase III study of docetaxel and S-1, patients received docetaxel 40 mg/m2 on day 1 and S-1 80 mg/m2 on days 1–14 every 3 weeks [26]. In a phase II study of docetaxel, cisplatin, and S-1, patients received docetaxel 40 mg/m2 and cisplatin 60 mg/m2 on day 1, and S-1 80 mg/m2 on days 1–14 every 4 weeks [27]. Considering these studies, our dose, theoretically, could have been low if the cancer cells had resistance to chemotherapeutic agents other than docetaxel in docetaxel-based chemotherapy. Paclitaxel monotherapy may be active in such cases. Therefore, gastric cancers refractory to docetaxel-based chemotherapy are considered to have two characteristics of resistance: one is being refractory to chemotherapeutic agents including docetaxel, and the other is being refractory to agents other than docetaxel.

In the non-docetaxel group in the present study, the RR was 11.5%, median PFS was 82 days, and median OS was 143 days. Two phase II studies of weekly paclitaxel as second-line therapy and a retrospective study of weekly paclitaxel as third-line therapy, respectively, reported RRs of 16–24% and 23%, median PFS values of 2.6–4.2 months and 105 days, and median OS values of 7.8–8.0 months and 201 days [14, 15, 28]. In our study, most patients were heavily pretreated, and a large proportion had a PS of 2 (31%). These factors may account for the relatively poor response and survival as compared with the results of previous studies.

Overall, we found that the toxicity of weekly paclitaxel was acceptable. Grade 3 or 4 neutropenia occurred in only 8% of the prior-docetaxel group as compared with 11% of the non-docetaxel group, and there was no febrile neutropenia. Grade 3 anorexia and nausea occurred in 15 and 4% of the prior-docetaxel group and 11 and 8% of the non-docetaxel group, respectively. Although the incidence of anorexia was moderate, most patients with anorexia had peritoneal metastasis before receiving paclitaxel. Thus, weekly paclitaxel was well tolerated in the vast majority of patients.

In conclusion, our study showed that weekly paclitaxel was modestly active and safe in patients with advanced gastric cancer refractory to docetaxel-based chemotherapy. Our findings suggest that weekly paclitaxel might be a novel treatment option for patients with advanced gastric cancer who have disease progression after first-line therapy. Further investigations, including controlled clinical trials, are needed to confirm our findings.

References

Kamangar F, Dores GM, Anderson WF. Patterns of cancer incidence, mortality, and prevalence across five continents: defining priorities to reduce cancer disparities in different geographic regions of the world. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:2137–50.

Parkin DM, Pisani P, Ferlay J. Global cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin. 1999;49:33–64.

Power DG, Kelsen DP, Shah MA. Advanced gastric cancer—slow but steady progress. Cancer Treat Rev. 2010;36:384–92.

Ajani JA, Rodriguez W, Bodoky G, Moiseyenko V, Lichinitser M, Gorbunova V, et al. Multicenter phase III comparison of cisplatin/S-1 with cisplatin/infusional fluorouracil in advanced gastric or gastroesophageal adenocarcinoma study: the FLAGS trial. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:1547–53.

Boku N, Yamamoto S, Fukuda H, Shirao K, Doi T, Sawaki A, et al. Fluorouracil versus combination of irinotecan plus cisplatin versus S-1 in metastatic gastric cancer: a randomised phase 3 study. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10:1063–9.

Koizumi W, Narahara H, Hara T, Takagane A, Akiya T, Takagi M, et al. S-1 plus cisplatin versus S-1 alone for first-line treatment of advanced gastric cancer (SPIRITS trial): a phase III trial. Lancet Oncol. 2008;9:215–21.

Narahara H, Iishi H, Imamura H, Tsuburaya A, Chin K, Imamoto H, et al. Randomized phase III study comparing the efficacy and safety of irinotecan plus S-1 with S-1 alone as first-line treatment for advanced gastric cancer (study GC0301/TOP-002). Gastric Cancer. 2011;14:72–80.

Van Cutsem E, Moiseyenko VM, Tjulandin S, Majlis A, Constenla M, Boni C, et al. Phase III study of docetaxel and cisplatin plus fluorouracil compared with cisplatin and fluorouracil as first-line therapy for advanced gastric cancer: a report of the V325 Study Group. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:4991–7.

Ajani JA, Fairweather J, Dumas P, Patt YZ, Pazdur R, Mansfield PF. Phase II study of Taxol in patients with advanced gastric carcinoma. Cancer J Sci Am. 1998;4:269–74.

Cascinu S, Graziano F, Cardarelli N, Marcellini M, Giordani P, Menichetti ET, et al. Phase II study of paclitaxel in pretreated advanced gastric cancer. Anticancer Drugs. 1998;9:307–10.

Ohtsu A, Boku N, Tamura F, Muro K, Shimada Y, Saigenji K, et al. An early phase II study of a 3-hour infusion of paclitaxel for advanced gastric cancer. Am J Clin Oncol. 1998;21:416–9.

Yamada Y, Shirao K, Ohtsu A, Boku N, Hyodo I, Saitoh H, et al. Phase II trial of paclitaxel by three-hour infusion for advanced gastric cancer with short premedication for prophylaxis against paclitaxel-associated hypersensitivity reactions. Ann Oncol. 2001;12:1133–7.

Seidman AD, Berry D, Cirrincione C, Harris L, Muss H, Marcom PK, et al. Randomized phase III trial of weekly compared with every-3-weeks paclitaxel for metastatic breast cancer, with trastuzumab for all HER-2 overexpressors and random assignment to trastuzumab or not in HER-2 nonoverexpressors: final results of Cancer and Leukemia Group B protocol 9840. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:1642–9.

Kodera Y, Ito S, Mochizuki Y, Fujitake S, Koshikawa K, Kanyama Y, et al. A phase II study of weekly paclitaxel as second-line chemotherapy for advanced gastric cancer (CCOG0302 study). Anticancer Res. 2007;27:2667–71.

Shimoyama R, Yasui H, Boku N, Onozawa Y, Hironaka S, Fukutomi A, et al. Weekly paclitaxel for heavily treated advanced or recurrent gastric cancer refractory to fluorouracil, irinotecan, and cisplatin. Gastric Cancer. 2009;12:206–11.

Bissery MC, Guenard D, Gueritte-Voegelein F, Lavelle F. Experimental antitumor activity of taxotere (RP 56976, NSC 628503), a taxol analogue. Cancer Res. 1991;51:4845–52.

Verweij J, Clavel M, Chevalier B. Paclitaxel (Taxol) and docetaxel (Taxotere): not simply two of a kind. Ann Oncol. 1994;5:495–505.

Valero V, Jones SE, Von Hoff DD, Booser DJ, Mennel RG, Ravdin PM, et al. A phase II study of docetaxel in patients with paclitaxel-resistant metastatic breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16:3362–8.

Aravantinos G, Bafaloukos D, Fountzilas G, Christodoulou C, Papadimitriou C, Pavlidis N, et al. Phase II study of docetaxel–vinorelbine in platinum-resistant, paclitaxel-pretreated ovarian cancer. Ann Oncol. 2003;14:1094–9.

Sella A, Yarom N, Zisman A, Kovel S. Paclitaxel, estramustine and carboplatin combination chemotherapy after initial docetaxel-based chemotherapy in castration-resistant prostate cancer. Oncology. 2009;76:442–6.

Lin YC, Chang HK, Wang CH, Chen JS, Liaw CC. Single-agent docetaxel in metastatic breast cancer patients pre-treated with anthracyclines and paclitaxel: partial cross-resistance between paclitaxel and docetaxel. Anticancer Drugs. 2000;11:617–21.

Yonemori K, Katsumata N, Uno H, Matsumoto K, Kouno T, Tokunaga S, et al. Efficacy of weekly paclitaxel in patients with docetaxel-resistant metastatic breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2005;89:237–41.

Sawaki M, Ito Y, Hashimoto D, Mizunuma N, Takahashi S, Horikoshi N, et al. Paclitaxel administered weekly in patients with docetaxel-resistant metastatic breast cancer: a single-center study. Tumori. 2004;90:36–9.

Taguchi T, Aihara T, Takatsuka Y, Shin E, Motomura K, Inaji H, et al. Phase II study of weekly paclitaxel for docetaxel-resistant metastatic breast cancer in Japan. Breast J. 2004;10:509–13.

Taguchi T, Sakata Y, Kanamaru R, Kurihara M, Suminaga M, Ota J, et al. Late phase II clinical study of RP56976 (docetaxel) in patients with advanced/recurrent gastric cancer: a Japanese Cooperative Study Group trial (group A). Gan To Kagaku Ryoho. 1998;25:1915–24.

Fujii M. Chemotherapy for advanced gastric cancer: ongoing phase III study of S-1 alone versus S-1 and docetaxel combination (JACCRO GC03 study). Int J Clin Oncol. 2008;13:201–5.

Koizumi W, Nakayama N, Tanabe S, Sasaki T, Higuchi K, Nishimura K, et al. A multicenter phase II study of combined chemotherapy with docetaxel, cisplatin, and S-1 in patients with unresectable or recurrent gastric cancer (KDOG 0601). Cancer Chemother Pharmacol (Epub ahead of print).

Matsuda G, Kunisaki C, Makino H, Fukahori M, Kimura J, Sato T, et al. Phase II study of weekly paclitaxel as a second-line treatment for S-1-refractory advanced gastric cancer. Anticancer Res. 2009;29:2863–7.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ando, T., Hosokawa, A., Kajiura, S. et al. Efficacy of weekly paclitaxel in patients with advanced gastric cancer refractory to docetaxel-based chemotherapy. Gastric Cancer 15, 427–432 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10120-011-0135-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10120-011-0135-0