Abstract

Multiple independent genomic profiling efforts have recently identified clinically and molecularly distinct subgroups of ependymoma arising from all three anatomic compartments of the central nervous system (supratentorial brain, posterior fossa, and spinal cord). These advances motivated a consensus meeting to discuss: (1) the utility of current histologic grading criteria, (2) the integration of molecular-based stratification schemes in future clinical trials for patients with ependymoma and (3) current therapy in the context of molecular subgroups. Discussion at the meeting generated a series of consensus statements and recommendations from the attendees, which comment on the prognostic evaluation and treatment decisions of patients with intracranial ependymoma (WHO Grade II/III) based on the knowledge of its molecular subgroups. The major consensus among attendees was reached that treatment decisions for ependymoma (outside of clinical trials) should not be based on grading (II vs III). Supratentorial and posterior fossa ependymomas are distinct diseases, although the impact on therapy is still evolving. Molecular subgrouping should be part of all clinical trials henceforth.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Ependymoma is a histologically defined intrinsic tumor that involves the three major anatomic compartments (supratentorial brain, posterior fossa, and spinal cord) of the central nervous system and affects both children and adults. The current standard of care therapy for patients with intracranial ependymoma remains surgical resection combined with radiotherapy. The survival benefit of chemotherapy for ependymoma and the prognostic ability of histopathological grading criteria to risk-stratify patients are still both inconclusive and contentious. No molecular or tumor-specific immunohistochemical markers are in routine current clinical use for ependymoma. Recent advances in the biological characterization of ependymal tumors have demonstrated the existence of nine clinically, demographically, and molecularly distinct entities, with three occurring in each anatomic compartment. These findings offer new opportunities to create a precise, reliable, and objective platform for stratification of ependymoma patients, and the potential for altering therapeutic decisions based on molecular features. Herein, we discuss the current consensus on the molecular subgroups of intracranial ependymoma (WHO Grade II/III) in children and adults, as well as recommendations for integration into future clinical trial designs. These discussions and recommendations were made by a collection of neuro-oncologists, neurosurgeons, neuro-pathologists, radiation oncologists, and basic scientists, meeting at the global ependymoma consensus conference (Huntsville, Ontario, Canada in September 2015) (Fig. 1).

The utility of histologic grading of ependymoma in a molecular era

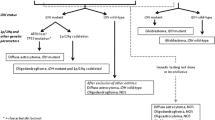

Ependymomas from throughout the central nervous system are currently sub-divided by three histology-based grades used to predict the natural course of the disease and patient outcome [19]. However, the utility of histological grading of ependymoma for risk stratification has been controversial and without consistent associations of tumor grade with patient outcome. The World Health Organization (WHO) Grade I tumors include myxopapillary ependymoma, which typically occurs in the spine, as well as subependymoma, which is usually intracranial. Grade I ependymomas are relatively easier to distinguish, occur predominantly in adults, and are associated with favorable clinical outcomes [19]. Conventional ependymomas are divided between WHO Grade II and WHO Grade III (anaplastic) tumors, the latter showing elevated mitotic activity, microvascular proliferation, and tumor necrosis. Analysis of multiple cohorts of intracranial ependymoma highlights a wide variance in the utility of the Grade II versus Grade III distinction as a robust prognostic marker [9]. Furthermore, the utility of conventional histologic grading may be confounded by the anatomic compartment [29, 37]. These considerations have raised significant questions as to whether the grading criteria should stratify patients into different therapeutic regimens. It was therefore agreed upon that: (1) treatment decisions for ependymoma should not be based on classification and grading that is solely based on histopathological characteristics (especially, the distinction of Grade II versus Grade III tumors) and (2) central and combined histologic–molecular review and classification should be a principal and integral component of any future clinical trial. Indeed, the updated 4th edition of the WHO classification of central nervous system tumors recognizes the supratentorial molecular variant, ST-EPN-RELA (see next section), as a distinct biological and clinical disease entity [20]. Integrated histo-molecular analyses of ependymal tumors from clinically well-annotated prospective international trial cohorts hold promise for inclusion of additional molecular ependymoma ‘entities’ into the upcoming 5th edition of the WHO classification of CNS tumors.

Molecular subgroups of ependymal tumors in the central nervous system

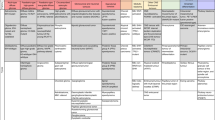

Although molecular subgroups of ependymoma arising in different anatomical sites exhibit histopathological similarities, their molecular profiles are easily discernable, owing to diverse genetic, transcriptional, and epigenetic programs [7, 8, 18, 22, 24, 30, 36, 37]. Functional cross-species analyses have provided evidence that these molecular differences may be reflective of discrete developmental and cellular origins [16, 30, 33]. Based on demographic, clinical, and molecular data, supported in multiple independent cohorts [23, 29–31, 36, 37], a full consensus was reached that: posterior fossa and supratentorial ependymoma are biologically different diseases both treated by surgery and radiotherapy. Future molecular characterization and clinical trials will assess whether posterior fossa and supratentorial ependymoma may benefit from different forms of therapy. A recent international collaborative study identified nine molecular subgroups of ependymal tumors, three in each anatomical compartment of the central nervous system, spine (SP), posterior fossa (PF), and supratentorial region (ST) [29]. One of the subgroups within each compartment was enriched with WHO Grade I subependymomas (SE), named ST-SE, PF-SE, and SP-SE. These molecular subependymomas occurred in adults only. The two other molecular subgroups within the spine predominantly matched the histopathology-based diagnoses of myxopapillary ependymoma (SP-MPE) and (WHO Grade II/III) ependymoma (SP-EPN). The remaining two molecular types of ependymoma occurred in the posterior fossa, termed PF-EPN-A and PF-EPN-B or alternatively posterior fossa Group A and B, and were independently identified in retrospective studies [36, 37]. PF-EPN-A tumors occur predominantly in infants and young children. Due to their predominant lateral localization, PF-EPN-A tumors are often difficult to completely resect and are associated with high recurrence rates [37]. Conversely, PF-EPN-B tumors occur largely in adolescents and young adults and are associated with a more favorable prognosis. More than 70% of supratentorial ependymomas are characterized by fusions between C11ORF95 and the RELA gene, and were recently termed ST-EPN-RELA [29, 30]. While ST-EPN-RELA tumors may occur in both children and adults, the remaining molecular subgroup of supratentorial ependymoma harbors recurrent fusions to the oncogene YAP1 and is enriched in the pediatric population [29, 30]. Since preliminary evidence of a small retrospective cohort indicates that patients with YAP1 fusions have an excellent prognosis, it was agreed upon that the international community should move rapidly toward determining whether ST-EPN-YAP1 is a subgroup with an extremely favorable clinical outcome and therefore might benefit from careful therapy de-escalation within the setting of a clinical trial. Retrospective classification of clinically well-annotated supratentorial ependymomas, which have been treated in clinical trials, is expected to give more detailed information on outcome within this subgroup in the near future. No consensus was made upon morphologically diagnosed ST-ependymomas without RELA/YAP1 fusion. It was felt that further investigation was needed for this apparently heterogeneous group of tumors. It was acknowledged that such issues could be addressed with a DNA methylation-based molecular classification for ependymal tumors that represents an unbiased, robust, and uniform scheme that adequately reflects the full biological, clinical, and histopathological heterogeneity across all age groups, grades, and major anatomical CNS compartments. The clinical feasibility of this platform is supported by multiple components: (1) low sample input and DNA requirements, (2) robust results from formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissue, and (3) minimal batch effects and assay consistency between different clinical-genomic facilities. In addition to DNA methylation patterns, DNA copy number profiles can be derived from this analysis. It is important to note that chromosome 1q gain has been shown to be an independent prognostic factor that occurs in a subset of PF-EPN-A, PF-EPN-B, and ST-EPN-RELA tumors [12, 17, 24, 29, 32, 37]. Future integrated molecular efforts will explore the integration of molecular subgroup, copy number alterations (namely chromosome 1q gain), and their impact on patient outcome.

Molecular sub-classification is expected to significantly support treatment decisions and simplify risk stratification processes in the immediate future, and should impact clinical trial design and operation in both children and adults. A complete consensus was reached that molecular subgrouping should be a part of all clinical trials moving forward. It was agreed that certification of diagnostic assays for molecular subgroup detection is of high importance. However, it was acknowledged that there were differences between countries regarding certifying agencies and regulations, and therefore most attendees felt that it was not reasonable and feasible to generate a consensus statement on certification processes. To further improve molecular diagnostics and identify new prognostic factors and therapeutic targets, optimal tissue material for ongoing and future biologic discovery studies is required. The great majority of attendees agreed that submitting fresh-frozen samples should be mandatory within upcoming clinical trials for ependymoma. Although DNA methylation profiling can be performed with FFPE-derived tissue, frozen samples would provide optimal material for use in future applications, such as genome sequencing. The interpretation of any tumor sequencing (from a limited gene panel up to whole genome) would dramatically benefit from a matched control to correct for aberrations inherent to the germline. As such, an agreement among most attendees was established that submission of blood samples should also be mandatory for enrollment in a clinical trial. It should be recognized that arguments were made against the mandate of fresh-frozen tissue, owing to the logistical issues of collection, storage, and submission, particularly in small community centers. Additionally, there were ethical concerns regarding the mandated submission of blood. Attendees recognized that efforts would need to be established to create standard operating procedures in smaller centers to enable reliable collection and submission of frozen tissue. Many of those agreeing on a mandate of frozen tissue and blood argued that given the rapid developments in the field of molecular genetics, with the emergence of increasingly powerful analytical devices and computational tools, the time is now to collect tissue specimens in combination with high-quality clinical data. This would enable the use of such advances to improve the care of future ependymoma patients.

Clinical management of intracranial ependymoma in the context of molecular subgroups

Clinical management of intracranial ependymomas (WHO Grade II/III) is challenging and the optimal treatment strategy is contentious. Intracranial ependymoma, particularly before administration of any therapy, demonstrates predominantly locally invasive growth patterns and has only very low metastatic potential. Surgery plays a primary role for local tumor control and the extent of neurosurgical resection has been the most consistent independent prognostic factor reported in the last decades [5, 6, 34]. The favorable outcome of patients without residual disease and the large difference in event-free and overall survival between patients with complete versus incomplete resection (up to 50% in some series) have led to the concepts of aggressive de-bulking and second-look surgery. Such neurosurgical procedures may be performed immediately following incomplete initial resection or after a short course of chemotherapy and is currently being systematically evaluated in clinical trials. A comprehensive radiological assessment of the residual disease status is expected to give the highest degree of information to base potential secondary neurosurgical intervention decisions. Attendees agreed that central radiological review of pre- and post-surgical imaging should be a principal component of every clinical trial enrolling patients with ependymoma henceforth.

In addition to surgery, post-operative field radiotherapy dosed at 54–59.4 Gy is considered the standard of care for patients with non-disseminated ependymoma to lower the risk of local recurrence [25]. Radiation margins around the target volume have also decreased from 2.0 to 1.0 cm, with no evidence of increased frequency of tumor relapse [25]. Owing to the challenging localization of ependymoma, particularly in the case of laterally located infant posterior fossa tumors, proton therapy has been explored as a radiation modality to spare proximal neurological structures [21]. In the case of recurrent ependymoma, a retrospective analysis demonstrated that the efficacy of re-irradiation, however, was associated with a decline in patient intellectual function [4].

It should be emphasized that all prior studies that evaluated the therapeutic value of neurosurgical interventions and external beam radiation in posterior fossa ependymoma have not accounted for molecular subgroup affiliation and might therefore be confounded by clinical differences in response to therapy between these subgroups. Data from a current retrospective study on four independent non-overlapping cohorts of posterior fossa ependymomas (n = 820 cases) found that patients with either PF-EPN-A or PF-EPN-B tumors benefit from gross total resection, with the survival rates being particularly poor for sub-totally resected PF-EPN-A, even in the setting of radiation therapy [31]. Participants at the conference concluded that for PF-EPN-A tumors in patients older than 12 months of age who are treated outside of clinical trials, maximal safe surgical resection and focal radiotherapy should be defined as the standard of care. Owing to the challenging localization of PF-EPN-A tumors, attendees acknowledged that patients would benefit from being treated in specialized centers by experienced neurosurgeons. Since the study strongly demonstrates that a large subset of patients with PF-EPN-B tumors who received a gross total resection did not recur, even in the absence of radiotherapy, it was agreed that a randomized clinical trial for newly diagnosed and gross totally resected PF-EPN-B ependymoma comparing observation versus standard upfront radiation should be considered. Such a trial would test the possibility of therapy to be de-escalated in some patients with PF-EPN-B ependymoma.

Observation for gross totally resected supratentorial ependymomas has also been advocated based on retrospective series that were not molecularly characterized. For example, a retrospective, multicenter study comprising 92 patients (median age was 17.5 years, range 1–83 years) with gross totally resected and non-anaplastic supratentorial ependymal tumors did not find evidence of decreased progression-free or overall survival with the omission of external beam radiation [11]. The 5–10 year Kaplan–Meier estimated overall survival for the overall cohort was 83.2 and 84.1%, respectively. Another retrospective review of only ten patients (median age 5.6 years, range 1.8–15.6 years), which also included ependymomas diagnosed as WHO grade III, found that in some children with completely resected supratentorial ependymoma, surgery alone may be an acceptable treatment option [35]. The outcomes in the aforementioned series differed from the largest cohort published to date comprising 122 supratentorial ependymal tumors that were classified according to their DNA methylation profiles as ST-EPN-RELA, ST-EPN-YAP1 and ST-SE [29]. Tumors harboring C11ORF95 gene fusions to RELA accounted for more than 70% of supratentorial ependymomas (median age 8 years, range 0–69 years) and were associated with a poor prognosis with 5-year progression-free and overall survival of 29 and 75%, respectively. Interestingly, the level of resection did not significantly affect the outcome within the ST-EPN-RELA-positive subgroup in this retrospective analysis in patient samples collected over a long period of time (>20 years). The two remaining supratentorial subgroups, ST-SE and ST-EPN-YAP1, were restricted only to adults (median age 40 years, range 22–76 years) and predominantly to children (median age 1.4 years, range 0–51 years), respectively, with both of these variants showing an excellent prognosis. As the cited studies and other available collections of single cases markedly differ regarding age distribution, therapy modalities and availability of molecular data, variations in outcome cannot be reliably linked to specific treatment approaches or molecular subgroups. It was, therefore, concluded that there was not enough evidence yet to recommend distinct treatment approaches for ST-EPN-RELA ependymoma. Molecular analyses of supratentorial ependymomas from clinically well-annotated international trial cohorts as well as from large retrospective cohorts with long-term follow-up have now been initiated. The authors expect that this approach will help to clarify questions about the clinical outcome of the molecular variants of supratentorial ependymoma and result in explicit therapy recommendations.

In contrast to surgery and radiotherapy, the role of chemotherapy in the management of ependymoma remains unproven despite extensive investigation. Cohorts of pediatric or adult patients in which the role of chemotherapy was retrospectively analyzed either failed to demonstrate a survival advantage or showed substantial variation between individual patients [3, 13, 28]. Two international randomized trials in children are currently comparing post-irradiation chemotherapy to observation only, SIOP Ependymoma II (Europe) and ACNS0831 (USA). In an attempt to delay radiotherapy in very young children, driven by concerns about long-term treatment toxicity, several groups used post-operative chemotherapy approaches in children under 3 years with 42% being the highest rate of 5-year progression-free survival reached to date [14, 15, 40]. In marked contrast, extension of immediate post-operative high-dose conformal radiotherapy to children under the age of 3 years led to 7-year progression-free survival rates of 77%, albeit long-term follow-up for toxic effects on development are still pending [25]. For this reason, radiotherapy deferral strategies that use chemotherapy have been abandoned in most institutions for children >12 months of age. Initial responses to chemotherapy after subtotal resection have been demonstrated [10] and the ependymoma trial ACNS0831 is currently assessing the role of neoadjuvant chemotherapy and second-look surgery, with a combined chemotherapy regimen of vincristine, cisplatin, etoposide, and cyclophosphamide. To date, there is no chemotherapeutic regimen that can routinely be recommended outside the context of a clinical trial. Since the consensus for therapeutic management in the molecularly well-defined PF-EPN-A subgroup does not include any systemic therapy, it will definitely open new avenues for rather rapid implementation of innovative trials for this devastating disease.

Model development and novel therapeutics

Because of the recognition that ependymal tumors comprise molecularly distinct subtypes, with potentially distinct clinical management, the generation of subgroup-specific pre-clinical models for the development and assessment of novel therapies is required. The identification of candidate cells of origin for ependymoma has permitted the generation of novel mouse models that can be leveraged for novel therapeutic discovery and evaluation [1, 16, 27, 30]. Ephrin receptor B2 (EPHB2)-driven ST ependymoma models—also highly expressed in ST-EPN-RELA tumors—have pinpointed 5-fluorouracil treatment as a potential cytotoxic therapy with efficacy in murine models and is currently being evaluated in early phase ependymoma clinical trials [1, 16, 38]. Owing to the clear genetic drivers of ST-EPN-RELA and ST-EPN-YAP1, transcriptionally faithful mouse models are currently generated, which will create similar opportunities to identify druggable targets against these specific subtypes of ependymoma [30]. In parallel, patient-derived xenograft (PDX) models have been established, permitting further therapeutic evaluation of novel drugs and compounds against ependymoma [2, 26, 39]. In the case of PF-EPN-A, the absence of a clear genetic driver has hampered efforts to create genetic mouse models of the disease. Moving forward, it will be important that pre-clinical models are developed in the context of ependymoma subgroups, such that molecular stratification of these tumors is paired with specific therapeutic targets.

Conclusions

We now recognize that ependymal tumors from different compartments of the central nervous system are biologically distinct and there are phenotypically divergent subgroups within each anatomic compartment. Future clinical trials, the development of pre-clinical model systems, and the identification and testing of subtype-specific therapeutics must accompany molecular classification to be useful to ependymoma patients and to the neuro-oncology community. The differentiation between histologically defined grade II versus grade III/anaplastic ependymomas is problematic and of limited utility for clinical decision-making, and therefore should be used with great caution outside the setting of a clinical trial. For patients with PF-EPN-A ependymoma over the age of 12 months of age, the recommended standard of care is maximal safe micro-neurosurgical removal followed by local radiotherapy, but probably does not include the routine use of chemotherapy outside the setting of a clinical trial. A subset of PF-EPN-B ependymoma patients who undergo gross total micro-neurosurgical resection are likely cured in the absence of radiotherapy, and a clinical trial to test the possibility to avoid radiotherapy in the context of complete resection for PF-EPN-B patients is indicated. The characteristics and heterogeneity between molecular subgroups of supratentorial ependymoma require additional study before specific treatment recommendations can be made. The division of an already uncommon entity (“ependymoma”) into nine new entities will necessitate great co-operation and international collaboration with the pediatric and adult neuro-oncology community if clinical trials are to be properly and expeditiously completed.

References

Atkinson JM, Shelat AA, Carcaboso AM, Kranenburg TA, Arnold LA, Boulos N, Wright K, Johnson RA, Poppleton H, Mohankumar KM et al (2011) An integrated in vitro and in vivo high-throughput screen identifies treatment leads for ependymoma. Cancer Cell 20:384–399. doi:10.1016/j.ccr.2011.08.013

Barszczyk M, Buczkowicz P, Castelo-Branco P, Mack SC, Ramaswamy V, Mangerel J, Agnihotri S, Remke M, Golbourn B, Pajovic S et al (2014) Telomerase inhibition abolishes the tumorigenicity of pediatric ependymoma tumor-initiating cells. Acta Neuropathol 128:863–877. doi:10.1007/s00401-014-1327-6

Bouffet E, Foreman N (1999) Chemotherapy for intracranial ependymomas. Child’s Nerv Syst ChNS 15:563–570

Bouffet E, Hawkins CE, Ballourah W, Taylor MD, Bartels UK, Schoenhoff N, Tsangaris E, Huang A, Kulkarni A, Mabbot DJ et al (2012) Survival benefit for pediatric patients with recurrent ependymoma treated with reirradiation. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 83:1541–1548. doi:10.1016/j.ijrobp.2011.10.039

Bouffet E, Perilongo G, Canete A, Massimino M (1998) Intracranial ependymomas in children: a critical review of prognostic factors and a plea for cooperation. Med Pediatr Oncol 30:319–329 (discussion 329–331)

Cage TA, Clark AJ, Aranda D, Gupta N, Sun PP, Parsa AT, Auguste KI (2013) A systematic review of treatment outcomes in pediatric patients with intracranial ependymomas. J Neurosurg Pediatr 11:673–681. doi:10.3171/2013.2.peds12345

Carter M, Nicholson J, Ross F, Crolla J, Allibone R, Balaji V, Perry R, Walker D, Gilbertson R, Ellison DW (2002) Genetic abnormalities detected in ependymomas by comparative genomic hybridisation. Br J Cancer 86:929–939. doi:10.1038/sj.bjc.6600180

Dyer S, Prebble E, Davison V, Davies P, Ramani P, Ellison D, Grundy R (2002) Genomic imbalances in pediatric intracranial ependymomas define clinically relevant groups. Am J Pathol 161:2133–2141. doi:10.1016/s0002-9440(10)64491-4

Ellison DW, Kocak M, Figarella-Branger D, Felice G, Catherine G, Pietsch T, Frappaz D, Massimino M, Grill J, Boyett JM et al (2011) Histopathological grading of pediatric ependymoma: reproducibility and clinical relevance in European trial cohorts. J Negat Results Biomed 10:7. doi:10.1186/1477-5751-10-7

Garvin JH Jr, Selch MT, Holmes E, Berger MS, Finlay JL, Flannery A, Goldwein JW, Packer RJ, Rorke-Adams LB, Shiminski-Maher T et al (2012) Phase II study of pre-irradiation chemotherapy for childhood intracranial ependymoma. Children’s Cancer Group protocol 9942: a report from the Children’s Oncology Group. Pediatr Blood Cancer 59:1183–1189. doi:10.1002/pbc.24274

Ghia AJ, Mahajan A, Allen PK, Armstrong TS, Lang FF Jr, Gilbert MR, Brown PD (2013) Supratentorial gross-totally resected non-anaplastic ependymoma: population based patterns of care and outcomes analysis. J Neurooncol 115:513–520. doi:10.1007/s11060-013-1254-8

Godfraind C, Kaczmarska JM, Kocak M, Dalton J, Wright KD, Sanford RA, Boop FA, Gajjar A, Merchant TE, Ellison DW (2012) Distinct disease-risk groups in pediatric supratentorial and posterior fossa ependymomas. Acta Neuropathol 124:247–257. doi:10.1007/s00401-012-0981-9

Gramatzki D, Roth P, Felsberg J, Hofer S, Rushing EJ, Hentschel B, Westphal M, Krex D, Simon M, Schnell O et al (2016) Chemotherapy for intracranial ependymoma in adults. BMC Cancer 16:287. doi:10.1186/s12885-016-2323-0

Grill J, Le Deley MC, Gambarelli D, Raquin MA, Couanet D, Pierre-Kahn A, Habrand JL, Doz F, Frappaz D, Gentet JC et al (2001) Postoperative chemotherapy without irradiation for ependymoma in children under 5 years of age: a multicenter trial of the French Society of Pediatric Oncology. J Clin Oncol 19:1288–1296

Grundy RG, Wilne SA, Weston CL, Robinson K, Lashford LS, Ironside J, Cox T, Chong WK, Campbell RH, Bailey CC et al (2007) Primary postoperative chemotherapy without radiotherapy for intracranial ependymoma in children: the UKCCSG/SIOP prospective study. Lancet Oncol 8:696–705. doi:10.1016/s1470-2045(07)70208-5

Johnson RA, Wright KD, Poppleton H, Mohankumar KM, Finkelstein D, Pounds SB, Rand V, Leary SE, White E, Eden C et al (2010) Cross-species genomics matches driver mutations and cell compartments to model ependymoma. Nature 466:632–636. doi:10.1038/nature09173

Kilday JP, Mitra B, Domerg C, Ward J, Andreiuolo F, Osteso-Ibanez T, Mauguen A, Varlet P, Le Deley MC, Lowe J et al (2012) Copy number gain of 1q25 predicts poor progression-free survival for pediatric intracranial ependymomas and enables patient risk stratification: a prospective European clinical trial cohort analysis on behalf of the Children’s Cancer Leukaemia Group (CCLG), Societe Francaise d’Oncologie Pediatrique (SFOP), and International Society for Pediatric Oncology (SIOP). Clin Cancer Res 18:2001–2011. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-11-2489

Korshunov A, Witt H, Hielscher T, Benner A, Remke M, Ryzhova M, Milde T, Bender S, Wittmann A, Schottler A et al (2010) Molecular staging of intracranial ependymoma in children and adults. J Clin Oncol 28:3182–3190. doi:10.1200/jco.2009.27.3359

Louis DN, Ohgaki H, Wiestler OD, Cavenee WK, Burger PC, Jouvet A, Scheithauer BW, Kleihues P (2007) The 2007 WHO classification of tumours of the central nervous system. Acta Neuropathol 114:97–109. doi:10.1007/s00401-007-0243-4

Louis DN, Perry A, Reifenberger G, von Deimling A, Figarella-Branger D, Cavenee WK, Ohgaki H, Wiestler OD, Kleihues P, Ellison DW (2016) The 2016 World Health Organization classification of tumors of the central nervous system: a summary. Acta Neuropathol 131:803–820. doi:10.1007/s00401-016-1545-1

Macdonald SM, Sethi R, Lavally B, Yeap BY, Marcus KJ, Caruso P, Pulsifer M, Huang M, Ebb D, Tarbell NJ et al (2013) Proton radiotherapy for pediatric central nervous system ependymoma: clinical outcomes for 70 patients. Neuro-oncology 15:1552–1559. doi:10.1093/neuonc/not121

Mack SC, Witt H, Piro RM, Gu L, Zuyderduyn S, Stutz AM, Wang X, Gallo M, Garzia L, Zayne K et al (2014) Epigenomic alterations define lethal CIMP-positive ependymomas of infancy. Nature. doi:10.1038/nature13108

Mack SC, Witt H, Wang X, Milde T, Yao Y, Bertrand KC, Korshunov A, Pfister SM, Taylor MD (2013) Emerging insights into the ependymoma epigenome. Brain Pathol (Zurich, Switzerland) 23:206–209. doi:10.1111/bpa.12020

Mendrzyk F, Korshunov A, Benner A, Toedt G, Pfister S, Radlwimmer B, Lichter P (2006) Identification of gains on 1q and epidermal growth factor receptor overexpression as independent prognostic markers in intracranial ependymoma. Clin Cancer Res 12:2070–2079. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-2363

Merchant TE, Li C, Xiong X, Kun LE, Boop FA, Sanford RA (2009) Conformal radiotherapy after surgery for paediatric ependymoma: a prospective study. Lancet Oncol 10:258–266

Milde T, Kleber S, Korshunov A, Witt H, Hielscher T, Koch P, Kopp HG, Jugold M, Deubzer HE, Oehme I et al (2011) A novel human high-risk ependymoma stem cell model reveals the differentiation-inducing potential of the histone deacetylase inhibitor Vorinostat. Acta Neuropathol 122:637–650. doi:10.1007/s00401-011-0866-3

Mohankumar KM, Currle DS, White E, Boulos N, Dapper J, Eden C, Nimmervoll B, Thiruvenkatam R, Connelly M, Kranenburg TA (2015) An in vivo screen identifies ependymoma oncogenes and tumor-suppressor gene. Nat Genet 47:878–887. doi:10.1038/ng.3323

Nuno M, Yu JJ, Varshneya K, Alexander J, Mukherjee D, Black KL, Patil CG (2016) Treatment and survival of supratentorial and posterior fossa ependymomas in adults. J Clin Neurosci 28:24–30. doi:10.1016/j.jocn.2015.11.014

Pajtler KW, Witt H, Sill M, Jones DT, Hovestadt V, Kratochwil F, Wani K, Tatevossian R, Punchihewa C, Johann P et al (2015) Molecular classification of ependymal tumors across all CNS compartments, histopathological grades, and age groups. Cancer Cell 27:728–743. doi:10.1016/j.ccell.2015.04.002

Parker M, Mohankumar KM, Punchihewa C, Weinlich R, Dalton JD, Li Y, Lee R, Tatevossian RG, Phoenix TN, Thiruvenkatam R et al (2014) C11orf95-RELA fusions drive oncogenic NF-kappaB signalling in ependymoma. Nature. doi:10.1038/nature13109

Ramaswamy V, Hielscher T, Mack SC, Lassaletta A, Lin T, Pajtler KW, Jones DT, Luu B, Cavalli FM, Aldape K et al (2016) Therapeutic impact of cytoreductive surgery and irradiation of posterior fossa ependymoma in the molecular era: a retrospective multicohort analysis. J Clin Oncol. doi:10.1200/jco.2015.65.7825

Rand V, Prebble E, Ridley L, Howard M, Wei W, Brundler MA, Fee BE, Riggins GJ, Coyle B, Grundy RG (2008) Investigation of chromosome 1q reveals differential expression of members of the S100 family in clinical subgroups of intracranial paediatric ependymoma. Br J Cancer 99:1136–1143. doi:10.1038/sj.bjc.6604651

Taylor MD, Poppleton H, Fuller C, Su X, Liu Y, Jensen P, Magdaleno S, Dalton J, Calabrese C, Board J et al (2005) Radial glia cells are candidate stem cells of ependymoma. Cancer Cell 8:323–335. doi:10.1016/j.ccr.2005.09.001

Tihan T, Zhou T, Holmes E, Burger PC, Ozuysal S, Rushing EJ (2008) The prognostic value of histological grading of posterior fossa ependymomas in children: a Children’s Oncology Group study and a review of prognostic factors. Modern Pathol 21:165–177. doi:10.1038/modpathol.3800999

Venkatramani R, Dhall G, Patel M, Grimm J, Hawkins C, McComb G, Krieger M, Wong K, O’Neil S, Finlay JL (2012) Supratentorial ependymoma in children: to observe or to treat following gross total resection? Pediatr Blood Cancer 58:380–383. doi:10.1002/pbc.23086

Wani K, Armstrong TS, Vera-Bolanos E, Raghunathan A, Ellison D, Gilbertson R, Vaillant B, Goldman S, Packer RJ, Fouladi M et al (2012) A prognostic gene expression signature in infratentorial ependymoma. Acta Neuropathol 123:727–738. doi:10.1007/s00401-012-0941-4

Witt H, Mack SC, Ryzhova M, Bender S, Sill M, Isserlin R, Benner A, Hielscher T, Milde T, Remke M et al (2011) Delineation of two clinically and molecularly distinct subgroups of posterior fossa ependymoma. Cancer Cell 20:143–157. doi:10.1016/j.ccr.2011.07.007

Wright KD, Daryani VM, Turner DC, Onar-Thomas A, Boulos N, Orr BA, Gilbertson RJ, Stewart CF, Gajjar A (2015) Phase I study of 5-fluorouracil in children and young adults with recurrent ependymoma. Neuro-oncology 17:1620–1627. doi:10.1093/neuonc/nov181

Yu L, Baxter PA, Voicu H, Gurusiddappa S, Zhao Y, Adesina A, Man TK, Shu Q, Zhang YJ, Zhao XM et al (2010) A clinically relevant orthotopic xenograft model of ependymoma that maintains the genomic signature of the primary tumor and preserves cancer stem cells in vivo. Neuro Oncol 12:580–594. doi:10.1093/neuonc/nop056

Zacharoulis S, Levy A, Chi SN, Gardner S, Rosenblum M, Miller DC, Dunkel I, Diez B, Sposto R, Ji L et al (2007) Outcome for young children newly diagnosed with ependymoma, treated with intensive induction chemotherapy followed by myeloablative chemotherapy and autologous stem cell rescue. Pediatr Blood Cancer 49:34–40. doi:10.1002/pbc.20935

Acknowledgements

The Ependymoma Consensus conference would like to thank the Robert Conner Dawes Foundation (RCD Foundation), Karine and Yannick Dumartineix (in memory of their son, Hugo), SickKids Garron Family Cancer Centre, The Pediatric Brain Tumor Foundation, Meagan’s Walk, b.r.a.i.n.child, Labatt Brain Tumour Research Centre, and Toronto Brain Tumour Research and Therapy Group for their invaluable support of the Ependymoma Consensus Panel meeting held in Huntsville, Ontario 2015.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Additional information

K. W. Pajtler and S. C. Mack contributed equally.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Pajtler, K.W., Mack, S.C., Ramaswamy, V. et al. The current consensus on the clinical management of intracranial ependymoma and its distinct molecular variants. Acta Neuropathol 133, 5–12 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00401-016-1643-0

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00401-016-1643-0