Abstract

To determine what capabilities wood-eating and detritivorous catfishes have for the digestion of refractory polysaccharides with the aid of an endosymbiotic microbial community, the pH, redox potentials, concentrations of short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), and the activity levels of 14 digestive enzymes were measured along the gastrointestinal (GI) tracts of three wood-eating taxa (Panaque cf. nigrolineatus “Marañon”, Panaque nocturnus, and Hypostomus pyrineusi) and one detritivorous species (Pterygoplichthys disjunctivus) from the family Loricariidae. Negative redox potentials (−600 mV) were observed in the intestinal fluids of the fish, suggesting that fermentative digestion was possible. However, SCFA concentrations were low (<3 mM in any intestinal region), indicating that little GI fermentation occurs in the fishes’ GI tracts. Cellulase and xylanase activities were low (<0.03 U g−1), and generally decreased distally in the intestine, whereas amylolytic and laminarinase activities were five and two orders of magnitude greater, respectively, than cellulase and xylanase activities, suggesting that the fish more readily digest soluble polysaccharides. Furthermore, the Michaelis–Menten constants (K m) of the fishes’ β-glucosidase and N-acetyl-β-d-glucosaminidase enzymes were significantly lower than the K m values of microbial enzymes ingested with their food, further suggesting that the fish efficiently digest soluble components of their detrital diet rather than refractory polysaccharides. Coupled with rapid gut transit and poor cellulose digestibility, the wood-eating catfishes appear to be detritivores reliant on endogenous digestive mechanisms, as are other loricariid catfishes. This stands in contrast to truly “xylivorous” taxa (e.g., beavers, termites), which are reliant on an endosymbiotic community of microorganisms to digest refractory polysaccharides.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The consumption of wood for food is rare among animals. Unlike the “greener” portions of plants, woody tissues are made of cells that are dead at functional maturity and, hence, lack the cell contents on which many herbivorous animals thrive. Because wood is composed almost entirely of structural polysaccharides (e.g., lignocellulose), it is considered to be nutrient poor (Karasov and Martínez del Rio 2007). Thus, many wood-eating, or xylivorous, animals (e.g., lower termites, beavers) require the aid of symbiotic microorganisms in their gastrointestinal (GI) tracts to digest cellulose and make the energy in this compound available to the host (Prins and Kreulen 1991; Vispo and Hume 1995). Indeed, xylivorous animals possess an expanded hindgut or cecum in which microbes reside and produce cellulolytic enzymes to aid in the digestion of woody material (Prins and Kreulen 1991; Vispo and Hume 1995; Mo et al. 2004). Because the conditions in this expanded hindgut are typically anaerobic, microbial endosymbionts operate under fermentative pathways, reducing glucose (and other monomers) to byproducts called short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs; e.g., acetate), which are then absorbed by the host animal and used to generate ATP (Bergman 1990; Karasov and Martínez del Rio 2007).

In 1993, Schaefer and Stewart described several new species as part of a lineage of neotropical catfishes, genus Panaque, which may possibly be xylivorous. The enlarged teeth these animals use to scrape wood from the surface of fallen trees in the river, and the presence of wood as the “only macroscopic material” in the fishes’ GI tracts intrigued the authors (Schaefer and Stewart 1993). Furthermore, xylivory evolved twice in loricariid catfishes, as a clade in the genus Hypostomus (Armbruster 2003) is recognized as wood-eating in addition to the Panaque (Fig. 1). Both xylivorous clades are derived within the phylogeny, but little is known of the digestive physiology of these fishes, and whether they can digest cellulose from wood.

Partial phylogenetic hypothesis for three tribes in the catfish family Loricariidae (Armbruster 2004). Phylogeny based on parsimony analysis of 214 morphological characters. See Armbruster (2004) for statistical support. Genera in bold include wood-eating species, and the asterisks (*) indicate genera from which species were investigated in this study. Numbers in parentheses indicate approximate number of taxa not shown

The xylivorous catfishes belong to the Loricariidae, a diverse catfish family (680 described species in 80 genera) endemic to the neotropics (Armbruster 2004). The diets of relatively few species of loricariids are known (Delariva and Agostinho 2001; Pouilly et al. 2003; de Melo et al. 2004; Novakowski et al. 2008; German 2009b) and appear to include animal, plant, and detrital material from the benthos. Loricariids are known to consume morphic (e.g., wood) and amorphic (i.e., unidentifiable colloidal material) detritus (German 2009b). It is clear, however, that these fishes have undergone evolutionary rearrangements of jaw structure, allowing for diversity in feeding modes and trophic specialization (Schaefer and Lauder 1986; Lujan 2009). Furthermore, loricariids have long, thin-walled intestines (Delariva and Agostinho 2001; German 2009b), which suggests that they have high levels of intake of low-quality food (Sibly and Calow 1986; Horn and Messer 1992; Karasov and Martínez del Rio 2007), such as detritus (Araujo-Lima et al. 1986). High intake equates to rapid gut transit and little endosymbiotic fermentation (Stevens and Hume 1998; Crossman et al. 2005; Karasov and Martínez del Rio 2007; German 2009a).

Nelson et al. (1999) examined digestive enzyme activities and cultured microbes from the GI tracts of Panaque maccus, and an undescribed species of Pterygoplichthys (formerly Liposarcus; Armbruster 2004), both of which they obtained via the aquarium trade. Nelson et al. were able to isolate aerobic microbes with cellulolytic capabilities from the guts of the two species and measured cellulase activities in the fishes’ GI tracts. From these results, Nelson et al. (1999) concluded that loricariids possess an endosymbiotic community in their guts capable of digesting cellulose under aerobic conditions. Conversely, German (2009b) showed that Panaque nigrolineatus and Pterygoplichthys disjunctivus passed wood through their guts in less than 4 h, could not assimilate significant amounts of cellulose from wood and, hence, did not thrive on a woody diet in the laboratory. What is clearly needed is an analysis of digestive tract function to better understand the digestive strategy of the wood-eating catfishes. Do these catfish GI tracts function more like those of other xylivorous animals (Breznak and Brune 1994; Vispo and Hume 1995; Felicetti et al. 2000), with some mechanism for slowing the flow of digesta and allowing microbes to ferment refractory polysaccharides (Clements and Raubenheimer 2006; Karasov and Martínez del Rio 2007), or are their guts more similar to those of other detritivorous fishes (Horn and Messer 1992; Crossman et al. 2005; German 2009a), with rapid gut transit, a reliance on endogenous digestive mechanisms and, hence, little digestion of refractory polysaccharides?

These divergent digestive strategies not only feature differences in digesta transit rate and gut morphology, but also involve completely different profiles of digestive enzyme activities and SCFA concentrations along the gut (Horn and Messer 1992; Jumars 2000; Crossman et al. 2005; Skea et al. 2005; Skea et al. 2007; German 2009a). For example, an animal reliant on hindgut fermentation would be expected to have high concentrations (>20 mM; Choat and Clements 1998) of SCFAs in its hindgut (Vispo and Hume 1995; Mountfort et al. 2002; Crossman et al. 2005; Pryor and Bjorndal 2005) and high activities of microbially produced digestive enzymes in this gut region (e.g., cellulase, Potts and Hewitt 1973; Nakashima et al. 2002; Mo et al. 2004). On the other hand, detritivorous fishes reliant on endogenous digestion show decreases in digestive enzyme activities distally in their intestines, low SCFA concentrations, and no pattern of SCFA concentrations along their GI tracts (Smith et al. 1996; Crossman et al. 2005; German 2009a).

In this study, we examined digestive enzyme activities, luminal carbohydrate profiles, and gastrointestinal fermentation in xylivorous and detrivorous loricariid catfishes to determine if these animals were capable of digesting a diet rich in refractory polysaccharides, and whether they were reliant on an endosymbiotic community to do so. Fishes were collected from their native habitat in the Río Marañon in northern Perú, where xylivorous catfishes are most diverse and abundant (Schaefer and Stewart 1993). In all, we collected two species from the genus Panaque (P. nocturnus Schaefer and Stewart 1993, and an undescribed species that we are calling P. cf. nigrolineatus “Marañon”; J. Armbruster, pers. comm.), representing the two clades of this genus, and one species of Hypostomus (H. pyrineusi Miranda-Ribeiro 1920) representing the other clade of xylivorous catfishes (Fig. 1). All of these taxa are sympatric in the Río Marañon. Additionally, we made use of an introduced population of a detritivorous loricariid, Pterygoplichthys disjunctivus (Weber 1991), which has been living in Florida for nearly two decades (Nico 2005; Nico et al. 2009). This study, therefore, included both clades of xylivorous catfishes and a less-derived detritivore from the same family (Fig. 1). Thus, we were able to examine the digestive physiology of closely related fishes with different diets, and those that converged independently on a woody diet.

This study had four main components. First, we measured the pH and redox conditions along the GI tracts of the fish to determine whether any portion of the gut would be hospitable to an anaerobic population of endosymbiotic microorganisms, or whether the fishes’ guts were aerobic, as proposed by Nelson et al. (1999). Second, luminal carbohydrate profiles and SCFA concentrations were measured along the GI tract to determine where nutrients were being hydrolyzed and absorbed, and where microbes might be most concentrated in the GI tract. If the fish were reliant on endosymbiont fermentation to gain energy from cellulose and other refractory polysaccharides, we would expect SCFA concentrations to be highest in the hindgut region. Third, we measured the biochemical activity levels of 14 digestive enzymes acting in the gut lumen or along the brush border of the intestine that reflect the ability of the fish to hydrolyze substrates commonly encountered in wood, algae, and detritus (Table 1). Following the methodology of Skea et al. (2005), we measured enzyme activities relative to location along the gut and determined whether the sources of these enzyme activities were endogenous (host-produced) or exogenous (produced by microorganisms). This was done by collecting three fractions from the gut sections: gut wall tissue (endogenous), gut fluid (enzymes secreted either by the fish or microorganisms), and microbial extract (exogenous). If, similar to other xylivorous animals, the catfishes were relying on endosymbionts in their hindgut to digest cellulose, we would expect refractory polysaccharide-degrading enzyme activities (e.g., cellulase) to be highest in the microbial extract of the hindgut region of the GI tract (Table 1). Digestive enzymes of endogenous origin (i.e., those produced by the fish, such as amylase, trypsin, and lipase) would be expected to show a pattern of decreasing activity toward the hindgut (German 2009a). And fourth, we measured the Michaelis–Menten (K m) constants of disaccharidases (maltase, β-glucosidase, and N-acetyl-β-d-glucosaminidase) produced by the fish (i.e., in gut wall tissue) and by microbes (i.e., in microbial extract) to determine if the fish were more efficient in digesting and assimilating disaccharides found in detritus than were microbes ingested with detritus.

Materials and methods

Fish collection

Ten adult individuals each of Panaque cf. nigrolineatus “Marañon” and P. nocturnus, and five adult individuals of Hypostomus pyrineusi were captured by seine and a backpack electroshocker from the upper Río Marañon in northern Peru (4°58.957′S, 77°85.283′W) in August 2006. Fourteen individuals of Pterygoplichthys disjunctivus were captured by hand while snorkeling from the Wekiva Springs complex in north central Florida (28°41.321′N, 81°23.464′W) in March 2006. Upon capture, fishes were placed in coolers of aerated river water and held until euthanized (up to 2 h). Fishes were euthanized in buffered water containing 1 g l−1 tricaine methanesulfonate (MS-222, Argent Chemicals Laboratory, Inc., Redmond, WA, USA), measured [standard length (SL) ± 1 mm], and dissected on a chilled (~4°C) cutting board. Guts were removed by cutting at the esophagus and at the anus and processed in a manner appropriate for specific analyses.

Gut pH and redox measurements

Upon dissection, the complete digestive tracts of four individuals each of P. cf. n. “Marañon”, P. nocturnus, and Pt. disjunctivus were placed on a sterilized, stainless-steel dissection tray at ambient temperature (22–25°C) and gently uncoiled without tearing or stretching. The pH and redox conditions of the digestive tracts were measured following Clements et al. (1994) with calibrated pH and redox microelectrodes (models PHR-146S and ORP-146, respectively; Lazar Laboratories Inc., Los Angeles, CA, USA) connected to a portable pH-redox meter (model 601A, Jenco Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). Incisions large enough to allow penetration of the microelectrode tip (~0.25 mm) into the gut fluid were made in the stomach and intestinal wall, and the pH and redox conditions were measured immediately after each incision was made. Overall, pH and redox conditions were measured in five sections of the stomach and ten sections each of the proximal, mid-, and distal intestine of each individual fish. The mean pH and redox conditions were then determined for each region of the digestive tract in an individual fish, and mean values determined for each gut region for each species. The pH and redox conditions were not measured in the intestines of H. pyrineusi because this species was not as abundant as the other taxa and, thus, we did not capture enough individuals for all of the analyses.

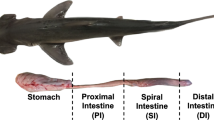

Tissue preparation for digestive enzyme analyses

For fishes designated for digestive enzyme analyses, guts were dissected out, placed on a sterilized, chilled (~4°C) cutting board, and uncoiled. The stomachs were excised, and the intestines divided into three sections of equal length representing the proximal, mid-, and distal intestine. The gut contents were gently squeezed from each of the three intestinal regions with forceps and the blunt side of a razor blade into sterile centrifuge vials. These vials (with their contents) were then centrifuged at 10,000×g for 5 min (Skea et al. 2005) in an Eppendorf 5415R desktop centrifuge powered by a 12 V car battery via a power inverter. Following centrifugation, the supernatants (heretofore called “intestinal fluid”) were gently pipetted into a separate sterile centrifuge vials, and the pelleted gut contents and intestinal fluid were frozen in liquid nitrogen. Gut wall sections were collected from each intestinal region of each specimen by excising an approximately 30 mm piece each of the proximal, mid-, and distal intestine. These intestinal pieces were then cut longitudinally, rinsed with ice-cold 0.05 M Tris–HCl buffer, pH 7.5, to remove any trace of intestinal contents, placed in sterile centrifuge vials, and frozen in liquid nitrogen. All of the samples were then transported on dry ice back to the University of Florida where they were stored at −80°C until analyzed.

The intestinal fluids and pelleted gut contents were homogenized on ice following Skea et al. (2005). Intestinal fluids were defrosted, diluted 5–10 volumes in 0.05 M Tris–HCl, pH 7.5, and gently homogenized using a Polytron homogenizer (Brinkmann Instruments, Westbury, NY) with a 7-mm generator at a setting of 1,100 rpm for 30 s. The intestinal fluid samples were then stored at −80°C in small aliquots (100–200 μl) until use. To ensure the rupture of microbial cells and the complete release of enzymes from the gut contents, the pelleted gut contents were defrosted, diluted 3–5 volumes in 0.05 M Tris–HCl, pH 7.5, sonicated at 5 W output for 3 × 20 s, with 40-s intervals between pulses, and homogenized with the Polytron homogenizer at 3,000 rpm for 3 × 30 s. The homogenized pelleted gut contents were then centrifuged at 12,000×g for 10 min at 4°C, and the resulting supernatant designated “microbial extract”.

Gut wall samples were homogenized according to German et al. (2004). Gut wall sections were defrosted, diluted in 5–100 volumes of 0.3 M mannitol in 0.001 M Hepes/NaOH (Martínez Del Rio et al. 1995; Levey et al. 1999), pH 7.0, homogenized with the Polytron homogenizer at 3,000 rpm for 3 × 30 s, and centrifuged at 9,400×g for 2 min at 4°C. Following centrifugation, the supernatants from the pelleted gut contents (microbial extract) and the gut wall sections were collected and stored in small aliquots (100–200 μl) at −80°C until just before use in spectrophotometric assays of activities of digestive enzymes. The protein content of the homogenates was measured using bicinchoninic acid (Smith et al. 1985), as detailed by German (2009a). Liver and hepatopancreas tissues were also prepared for enzymatic analyses as described by German (2008).

All assays of digestive enzyme activity were carried out at 25°C, consistent with the measured temperatures (24–26°C) of the Río Marañon, in triplicate using the BioRad Benchmark Plus microplate spectrophotomer and Falcon flat-bottom 96-well microplates (Fisher Scientific). All pH values listed for buffers were measured at room temperature (22°C), and all reagents were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Chemical (St. Louis). All reactions were run at saturating substrate concentrations as determined for each enzyme with gut tissues from the four species. Each enzyme activity (Table 1) was measured in each gut region of each individual fish, and blanks consisting of substrate only and homogenate only (in buffer) were conducted simultaneously to account for endogenous substrate and/or product in the tissue homogenates and substrate solutions (Skea et al. 2005; German et al. 2009).

Assays of polysaccharide degrading enzymes

Polysaccharidase activities (i.e., activities against starch, laminarin, cellulose, mannan, and xylan) were measured in the intestinal fluid and microbial extracts according to the Somogyi–Nelson method (Nelson 1944; Somogyi 1952). Polysaccharide substrate was dissolved [starch (2%), laminarin (0.5%), carboxymethyl cellulose (0.5%), or mannan (0.5%)] or suspended (xylan, 0.5%) in 0.8 M sodium citrate buffer, pH 7.5, containing 0.001% sodium azide. In a microcentrifuge vial, 50 μl of polysaccharide solution was combined with 50 μl of a mixture of sodium citrate buffer and intestinal fluid, tissue, or microbial extract homogenate. Homogenate volumes ranged from 1 to 30 μl, depending on the enzyme concentration in the homogenates. The incubation period varied with substrate: the assays were carried out for 10 min for starch, 2 h for laminarin, each in a water bath, and 24 h for each of carboxymethyl cellulose, mannan, and xylan, under constant shaking on a rotary shaker in an incubator. The 24-h incubations also included 1 μl of protease inhibitor (Sigma P8340) to prevent the degradation of polysaccharide degrading enzymes by proteases during the assay period. The incubations were stopped by adding 20 μl of 1 M NaOH and 200 μl of Somogyi–Nelson reagent A. Somogyi–Nelson reagent B was added after the assay solution was boiled for 10 min (see German et al. 2004 for reagent recipes). The resulting solution was diluted in water and centrifuged at 6,000×g for 5 min. The reducing sugar content of the solution was then determined spectrophotometrically at 650 nm, and polysaccharidase activity was determined from a standard curve constructed with the respective monomer (i.e., glucose for starch, laminarin, and carboxymethyl cellulose; mannose for mannan; and xylose for xylan). Enzyme activities are expressed in U (1 μmol reducing sugar liberated per minute) per gram wet weight of fluid, tissue, or content.

Chitinase activities were measured following German et al. (2009), but no activity was detected in the four species used in this study. In all assays, the background levels of N-acetyl-glucosamine detected in the blanks (>1 mM) matched what was measurable in the assay mixtures, making activity determinations impossible. However, the measurable N-acetyl-glucosamine in the gut in addition to measurable N-acetyl-glucosaminidase activities makes it likely that the fish can utilize chitin as a nutrient source.

Assays of disaccharidases

Maltase activity was measured in gut wall tissues and pelleted gut contents following Dahlqvist (1968) as described by German (2009a). In a microcentrifuge tube, 10 μl of 56 mM maltose dissolved in 100 mM maleate buffer, pH 7.0, was combined with 10 μl of regional gut wall or microbial extract homogenate. After 10 min, the reaction was stopped by the addition of 300 μl of assay reagent (Sigma GAGO20) dissolved in 1 M Tris–HCl, pH 7.0. The reaction mixture was incubated for 30 min at 37°C and was stopped by the addition of 300 μl of 12 N H2SO4. The amount of glucose in the solution was then determined spectrophotometrically at 540 nm. The maltase activity was determined from a glucose standard curve and expressed in U (1 μmol glucose liberated per minute) per gram wet weight of gut tissue or pelleted contents. The Michaelis–Menten constant (K m) for maltase was determined for gut wall and microbial extract samples with substrate concentrations ranging from 0.56 to 112 mM.

Tris is known to be an inhibitor of maltase activity (Dahlqvist 1968), but in higher concentrations (e.g., 1 M; Levey et al. 1999) than those used in our homogenate buffer (0.05 M). Nevertheless, to confirm that the different buffers used for the gut wall (Hepes–mannitol) and microbial extract (Tris–HCl) homogenates did not directly affect the K m or activity for maltase, the gut walls and pelleted gut contents of the proximal intestine of five additional Pt. disjunctivus were homogenized in the opposite buffers: gut walls in Tris–HCl and pelleted gut contents in Hepes–mannitol. For maltase, the different buffers did not produce different K m (Tris–HCl: 7.72 ± 1.91 mM; Hepes–mannitol: 7.97 ± 0.99 mM; t = 0.10, P = 0.92, df = 10) or activity (Tris–HCl: 20.74 ± 4.76 U g tissue−1; Hepes–mannitol: 12.62 ± 1.66 U g tissue−1; t = 1.38, P = 0.20, df = 10) values in the microbial extract, or K m (Tris–HCl: 4.98 ± 0.72 mM; Hepes–mannitol: 3.87 ± 0.58 mM; t = 1.20, P = 0.26, df = 10) or activity (Tris–HCl: 2.05 ± 0.41 U g tissue−1; Hepes–mannitol: 2.44 ± 0.37 U g tissue−1; t = 0.70, P = 0.50, df = 10) values in the gut wall homogenates. The low-concentration Tris–HCl was observed to have little effect on maltase activity in two previous investigations (German et al. 2004; German 2009a) in which the gut tissues were homogenized in 0.05 M Tris–HCl buffer. The different buffers also did not affect the K m and activity levels of the other disaccharidases measured in this study (see below) and, thus, we can be confident that any differences in K m and enzyme activity among the gut wall and microbial extract homogenates are not due to the different buffers used in their homogenization.

The activities of the disaccharidases β-glucosidase, β-mannosidase, β-xylosidase, and N-acetyl-β-d-glucosaminidase (NAG) were measured in gut wall tissues and microbial extracts using p-nitrophenol conjugated substrates (Nelson et al. 1999; Xie et al. 2007) dissolved in 0.1 M sodium citrate, pH 7.0. In a microplate well, 90 μl of 11.1 mM substrate (1.33 mM for NAG) was combined with 10 μl of gut wall or microbial extract homogenate and the reaction was read kinetically at 405 nm for 15 min. The disaccharidase activities were determined from a p-nitrophenol standard curve and expressed in U (1 μmol p-nitrophenol liberated per minute) per gram wet weight of gut tissue or pelleted contents. The K m was determined for gut wall and microbial extract samples for β-glucosidase and NAG. The substrate concentrations ranged from 0.1 to 12 mM for β-glucosidase and 0.04–1.2 mM for NAG.

Assays of proteases and lipase

Trypsin activity was assayed in the intestinal fluid and microbial extract using a modified version of the method designed by Erlanger et al. (1961), as described by Gawlicka et al. (2000). The substrate, 2 mM Nα-benzoyl-l-arginine-p-nitroanilide hydrochloride (BAPNA), was dissolved in 100 mM Tris–HCl buffer (pH 7.5) by heating to 95°C (Preiser et al. 1975; German et al. 2004). In a microplate, 95 μl of BAPNA was combined with 5 μl of homogenate, and the increase in absorbance was read continuously at 410 nm for 15 min. Trypsin was also assayed in the liver and hepatopancreas, but tissues homogenates from these organs were first incubated with enterokinase for 15 min to activate trypsinogen prior to combining the homogenates with substrate (German et al. 2004). Trypsin activity was determined with a p-nitroaniline standard curve and expressed in U (1 μmol p-nitroaniline liberated per minute) per gram wet weight of tissue, gut fluid, or microbial extract.

Aminopeptidase activity was measured in gut wall tissues and microbial extracts according to Roncari and Zuber (1969), as described by German et al. (2004). In a microplate, 90 μl of 2.04 mM l-alanine-p-nitroanilide HCl dissolved in 200 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.5) was combined with 10 μl of homogenate. The increase in absorbance was read continuously at 410 nm for 15 min and activity determined with a p-nitroaniline standard curve. Aminopeptidase activity was expressed in U (1 μmol p-nitroaniline liberated per minute) per gram wet weight of gut tissue or pelleted gut contents.

Lipase (nonspecific bile-salt activated E.C. 3.1.1.-) activities were assayed in the intestinal fluids and microbial extracts using a modified version of the method designed by Iijima et al. (1998). In a microplate, 86 μl of 5.2 mM sodium cholate dissolved in 250 mM Tris–HCl (pH 7.5) was combined with 6 μl of homogenate and 2.5 μl of 10 mM 2-methoxyethanol and incubated at room temperature for 15 min to allow for lipase activation by bile salts. The substrate p-nitrophenyl myristate (5.5 μl of 20 mM p-nitrophenyl myristate dissolved in 100% ethanol) was then added and the increase in absorbance was read continuously at 405 nm for 15 min. Lipase activity was determined with a p-nitrophenol standard curve and expressed in U (1 μmol p-nitrophenol liberated per minute) per gram wet weight of gut tissue.

The activity of each enzyme was regressed against the protein content of the homogenates to confirm that there were no significant correlations between the two variables. Because no significant correlations were observed, the data are not reported as U per mg protein.

Gut fluid preparation, gastrointestinal fermentation, and luminal carbohydrate profiles

Measurements of symbiotic fermentation activity were based on the methods of Pryor and Bjorndal (2005). Fermentation activity was indicated by relative concentrations of short-chain fatty acids (SCFA) in the fluid contents of the guts of the fishes at the time of death. As homogenates were prepared from the intestinal fluid samples (see “Tissue preparation for digestive enzyme analyses”), 30 μl of undiluted intestinal fluid was pipetted into a sterile centrifuge vial equipped with a 0.22 μm cellulose acetate filter (Costar Spin-X gamma sterilized centrifuge tube filters, Coming, NY) and centrifuged under refrigeration at 13,000×g for 15 min to remove particles from the fluid (including bacterial cells). The filtrates were collected and frozen until they were analyzed for SCFA and nutrient concentrations.

Concentrations of SCFA in the intestinal fluid samples from each gut region in each species were measured using gas chromatography as described by Pryor et al. (2006) and German et al. (2009). Glucose concentrations were analyzed in 2 μl of gut fluid using the same glucose content assay described for the maltase assay above, the only departure being that there was no pre-incubation with maltose.

To examine the presence of reducing sugars of various sizes in the intestinal fluids of the fish, 1 μl of filtered intestinal fluid was spotted on to pre-coated silica gel plates (Whatman, PE SIL G) together with standards of glucose, maltose, and tri- to penta-oligosaccharides of glucose. The thin layer chromatogram (TLC) was developed with ascending solvent (isopropanol/acetic acid/water, 7:2:1 (v/v)) and stained with thymol reagent (Adachi 1965; Skea et al. 2005).

Statistical analyses

Prior to all significance tests, a Levene’s test for equal variance was performed and residual versus fits plots were examined to ensure the appropriateness of the data for parametric analyses. All tests were run using SPSS (version 11) and Minitab (version 12) statistical software packages. Amylolytic, laminarinase, cellulase, and xylanase activities were compared between the intestinal fluid and microbial extract fractions of each gut region in each species with t test, using a Bonferroni correction. Intraspecific comparisons of total enzymatic activities (intestinal fluid + microbial extract) and total SCFA concentrations among the gut regions of each species were made with ANOVA followed by a Tukey’s HSD with a family error rate of P = 0.05. The numerical data for the enzyme activities are presented separately (in figures) from the actual statistical and P values (in tables). The activities of maltase, β-glucosidase, N-acetyl-β-d-glucosaminidase, β-mannosidase, and aminopeptidase were compared between the gut wall and microbial extract fractions of each gut region in each species with t test, using a Bonferroni correction. Similarly, the K m values of maltase, β-glucosidase, and N-acetyl-β-d-glucosaminidase from the proximal intestine of the fish were compared between the gut wall and microbial extract fractions of each species with t test.

Results

Gut pH and redox conditions

The pH of the digestive tracts of P. cf. n. “Marañon”, P. nocturnus, and Pt. disjunctivus were all neutral, whereas the redox conditions of the stomach were positive (Pt. disjunctivus) or less negative (P. cf. n. “Marañon”and P. nocturnus), and the redox conditions of the intestines of all three species were negative (see Supplemental Table S1 in online version). Thus, the guts of the three species were aerobic or slightly anaerobic in the stomach region, and definitively anaerobic along the intestine.

Polysaccharide degrading enzyme activities

No differences were observed in amylolytic, laminarinase, or cellulase activities between the intestinal fluid and the microbial extracts of any species (See Supplemental Table S2 in online version). However, xylanase activity was significantly greater in the microbial extracts of the proximal and mid-intestine of P. nocturnus than in the intestinal fluids of these regions. Total amylolytic activity was significantly greater in the proximal intestine than in the distal intestine of all four species (Table 2; Fig. 2).

Total (intestinal fluid + microbial extract) amylolytic, laminarinase, cellulase, and xylanase activities in three regions of the intestine of Panaque cf. nigrolineatus “Marañon” (Pm), P. nocturnus (Pn), Pterygoplichthys disjunctivus (Ptd), and Hypostomus pyrineusi (Hp). Values are means and error bars represent SEM. Intraspecific comparisons of each enzyme among gut regions were made with ANOVA followed by a Tukey’s HSD with a family error rate of P = 0.05. Regional activity levels for a specific enzyme and species that share a letter are not significantly different. No letters above the gut regions for a particular enzyme indicate that there are no differences in activity among the intestinal regions for that species. Interspecific comparisons among species were not made

Laminarinase activity was significantly higher in the proximal intestine of all four species than in their mid- or distal intestines (Table 2; Fig. 2). No laminarinase activity was detected in the distal intestines of P. nocturnus and H. pyrineusi.

Pterygoplichthys disjunctivus and H. pyrineusi exhibited significantly higher cellulase activity in their proximal intestines than in their mid- or distal intestines (H. pyrineusi lacked detectable cellulase activity in its distal intestine), whereas the two species of Panaque showed no difference in cellulase activity along the gut (Table 2; Fig. 2).

Individuals of P. cf. n. “Marañon”, Pt. disjunctivus, and H. pyrineusi possessed significantly greater xylanase activity in their proximal intestines than in their mid- or distal intestines (like cellulase, H. pyrineusi lacked detectable xylanase activity in its distal intestine). Panaque nocturnus, on the other hand, showed a slight, but insignificant increase in xylanase activity moving distally along its intestine (Table 2; Fig. 2). No mannanase activity was detected in any gut region of any species.

Disaccharidase activities

The maltase activity in the microbial extract was significantly higher than the activity of this enzyme in the gut wall of the proximal intestines of all four species (Figs. 3, 4). No significant differences were observed in the mid-intestine. The maltase activity in the gut walls of the distal intestines of the wood-eating taxa was higher than the maltase activity of the microbial extract, whereas the opposite was true for the detritivorous Pt. disjunctivus (Figs. 3, 4). All four species showed decreasing maltase activities in the microbial extract distally in the intestine, whereas all four taxa showed slight increases in gut wall maltase activity in the mid-intestine in comparison to the proximal intestine (Figs. 3, 4).

Maltase, β-glucosidase, and N-acetyl-β-d-glucosaminidase (NAG) activities in the gut walls and microbial extracts of the proximal intestine (PI), mid-intestine (MI), and distal intestine (DI) of Panaque cf. nigrolineatus “Marañon” (left column) and P. nocturnus (right column). Comparisons were made of the activities of each enzyme between the gut walls and microbial extracts of each gut region with t test. Following a Bonferroni correction for each enzyme and species, differences are considered significant at P = 0.013 [indicated with an asterisk (*)]

Maltase, β-glucosidase and N-acetyl-β-d-glucosaminidase (NAG) activities in the gut walls and microbial extracts of the proximal intestine (PI), mid-intestine (MI), and distal intestine (DI) of Pterygoplichthys disjunctivus (left column) and Hypostomus pyrineusi (right column). Comparisons were made of the activities of each enzyme between the gut walls and microbial extracts of each gut region in each species with t test. Following a Bonferroni correction for each enzyme and species, differences are considered significant at P = 0.013 [indicated with an asterisk (*)]

The β-glucosidase activities in the microbial extracts of the proximal intestines of P. cf. n. “Marañon”, P. nocturnus, and Pt. disjunctivus were all significantly higher than the activities of this enzyme in the gut wall fractions; however, the opposite was true for H. pyrineusi (Figs. 3, 4). Only Pt. disjunctivus showed significant differences in β-glucosidase activity in their mid- and distal intestines, with the gut wall activity being significantly higher in the mid-intestine, and the activity in the microbial extract being higher in the distal intestine. All four species showed decreasing β-glucosidase activity in the microbial extracts of their distal intestines (Figs. 3, 4). However, there were several different patterns for gut wall β-glucosidase activity: P. nocturnus and H. pyrineusi showed decreasing activity in their distal intestine, P. cf. n. “Marañon” showed increasing activity toward their distal intestine, and Pt. disjunctivus showed a spike in activity in the mid-intestine, followed by a decrease in the distal intestine.

Panaque nocturnus exhibited significantly greater N-acetyl-β-d-glucosaminidase (NAG) activity in the gut wall of its proximal intestine than in the microbial extract, whereas none of the other species showed differences in NAG activity between these two fractions in their proximal intestines (Figs. 3, 4). The wood-eating taxa all exhibited significantly higher NAG activity in the gut walls of their mid-intestines than in the microbial extracts from this gut region, whereas Pt. disjunctivus showed no differences between the two fractions. However, P. nocturnus and Pt. disjunctivus had significantly greater NAG activity in the gut walls of their distal intestine than in their microbial extracts, whereas the other species showed no differences between the two fractions (Figs. 3, 4). Panaque cf. n. “Marañon”, P. nocturnus, and Pt. disjunctivus showed increases in their gut wall NAG activities distally in the intestine, whereas H. pyrineusi showed a decrease. The NAG activities of the microbial extracts were variable and did not follow one pattern (increase or decrease) along the guts of any of the four species (Figs. 3, 4).

The maltase Michaelis–Menten constants (K m) from the wall of the proximal intestines of the fish were generally lower, although not significantly so, than the K m values of the microbial extracts from the proximal intestines (Table 3). However, the K m values of β-glucosidase were all significantly lower in the fish gut walls than in the microbial extracts, and the same was generally true for NAG, except for P. nocturnus (Table 3).

All four species generally possessed significantly greater β-mannosidase activities in their gut walls than in the microbial extracts (See Supplemental Table S3 in online version). β-mannosidase activity increased in the distal intestine of P. cf. n. “Marañon”, decreased in the distal intestines of P. nocturnus and Pt. disjunctivus, and spiked in the mid-intestine of H. pyrineusi.

β-xylosidase activity was only observed in the microbial extracts of the four taxa and was absent in the distal intestines of P. nocturnus, Pt. disjunctivus, and H. pyrineusi (Supplemental Table S3). Panaque cf. n. “Marañon” showed significant decreases in β-xylosidase activity distally in its intestine (ANOVA F 2,17 = 10.24, P = 0.002). Similarly, Pterygoplichthys disjunctivus (t = 2.57, P = 0.019, df = 18) and H. pyrineusi (t = 2.25, P = 0.050, df = 8) showed significant decreases in β-xylosidase activity in their mid-intestines compared to their proximal intestines, whereas P. nocturnus (t = 0.84, P = 0.421, df = 10) did not.

Protease and lipase activities

Trypsin activities significantly decreased distally in the intestines of all four species (Table 2, Supplemental Fig. S1 in online version).

All four species generally possessed significantly greater aminopeptidase activities in their gut walls than in the microbial extracts (Table 4). Aminopeptidase activities increased distally in the intestine in the wood-eating taxa, and spiked in the mid-intestine of Pt. disjunctivus (Table 4).

Lipase activities significantly decreased distally in the intestines of all of the wood-eating taxa, but slightly increased in the distal intestines of Pt. disjunctivus (Table 2, Supplemental Fig. S1).

Enzymatic activities of the hepatopancreas and liver (not shown) varied by enzyme. No cellulase or xylanase activities were detected in the hepatpancreas or liver of any species, whereas amylolytic activity, laminarinase, trypsin, and lipase were all detected in the hepatopancreas of the fish. Only amylolytic and lipase activities were detectable in the liver.

Gastrointestinal fermentation and luminal carbohydrate profiles

Hypostomus pyrineusi was the only catfish species to show any significant change in SCFA concentration along the gut, with significantly higher SCFA concentrations in the mid-intestine than in the proximal intestine (Table 5). The trends of SCFA concentrations varied among species, with Pt. disjunctivus showing an increasing concentration of SCFAs along the gut, and P. cf. n. “Marañon” showing a decrease, albeit no significant change (Table 5). The TLC plates (not shown) revealed that all four species had soluble oligo-, di-, and monosaccharides in the proximal intestine, and that these concentrations decreased until there were no soluble sugars remaining in the distal intestine. Similarly, measurable glucose was observed in the fluid of the proximal intestine of P. cf. n. “Marañon” (2.70 ± 0.29 mM) and P. nocturnus (2.86 ± 0.38 mM), but these concentrations disappeared in the mid- and distal intestine. Only H. pyrineusi showed measurable glucose in all regions of the intestine and these concentrations decreased, significantly so (ANOVA: F2,14 = 84.75, P < 0.001), from the proximal (4.98 ± 0.43 mM) to the mid- (0.93 ± 0.09 mM) to the distal (0.73 ± 0.03 mM) intestine. No glucose was detected in the fluid of any gut region of Pt. disjunctivus.

Discussion

The results of this study support the null hypothesis that wood-eating catfishes are not reliant upon endosymbionts to digest refractory polysaccharides in their GI tracts. First, even though negative redox conditions were observed in the intestinal fluids of the fishes, the SCFA concentrations were low and were not significantly greater in the distal intestine than in the other gut regions. Second, the profiles of soluble oligosaccharides in the intestinal fluids of the fish indicate that most absorption of nutrients takes place in their proximal and mid-intestines, and not in their distal intestines. Third, the patterns of digestive enzyme activities indicate that the fish target more soluble components of their detrital diet rather than refractory polysaccharides: cellulase and xylanase activities were low, variable, and generally decreased in the distal intestines of the fish; cellulase and xylanase activities were not higher in the microbial extracts, as would be expected in animals reliant on an endosymbiotic community; cellulase and xylanase activities were several orders of magnitude lower than amylolytic and laminarinase activities; and the K m values of maltase, β-glucosidase, and N-acetyl-β-d-glucosaminidase (NAG) were generally lower in the walls of the proximal intestines of the fish than in the microbial extracts, suggesting that the fish more efficiently digest soluble disaccharides than do microbial enzymes ingested with their food. Thus, consistent with our observations of rapid gut transit and poor cellulose digestibility in these fishes (German 2009b), the wood-eating loricariid catfishes appear to be more similar, from a digestive physiology standpoint, to their closely related detritivorous relatives in the genus Pterygoplichthys than to other xylivores (e.g., beavers, termites).

The pH levels and redox potentials in the catfish intestines indicated the possibility of supporting a population of anaerobic microbes, but only in the intestine. Many loricariids breathe air and have modified stomachs that are considered to be air breathing organs (Graham and Baird 1982; Armbruster 1998), which explains why the redox potentials of the stomachs of the fish in this study were positive (Pt. disjunctivus) or only slightly negative (P. cf. n. “Marañon” and P. nocturnus; Table S1). However, the loricariid stomach is not involved in digestion. For example, the stomach of Pt. disjunctivus is usually filled with air, is alkaline, and ingesta are not held in the stomach for any length of time; even individuals of this species killed minutes after consuming food had already passed the ingesta into the proximal intestine, bypassing the stomach via a small groove at its base (DPG, pers. obs.). Redox potentials measured 1 mm beyond the pyloric sphincter in this study were already −600 mV, which indicated that even the most proximal region of the intestine was not oxygenated by the fish’s breathing activity. Furthermore, similar to some detritivorous termites (Kappler and Brune 2002), detritivorous fishes (including wood-eating species) probably consume humic acids, which, in addition to other components of the intestinal fluid (e.g., bile salts and ingested metals; Kappler and Brune 2002), can increase the reductive potential, thus producing negative redox conditions. Either way, the redox potentials measured in wild-caught fish in this study suggest that the intestinal environment is highly reductive.

The concentrations of SCFAs observed in the fishes’ intestines further challenge the hypothesis that wood-eating catfishes use an endosymbiotic community to ferment recalcitrant polysaccharides. Fishes that rely on GI fermentation to meet some proportion of their daily energy needs tend to have >20 mM total SCFAs in their hindguts (Choat and Clements 1998). The highest concentrations observed in this study were in the mid-intestine of H. pyrineusi (3.20 ± 0.79 mM) and were far below concentrations observed in fishes with active endosymbiotic communities in their GI tracts (Choat and Clements 1998; Mountfort et al. 2002). Furthermore, H. pyrineusi was the only species to show any significant difference in SCFA concentrations along its gut. Coupled with rapid gut transit, it appears that some detritivorous/microalgivorous fish species target more soluble components of their diet, especially protein, and do not readily digest refractory polysaccharides (Crossman et al. 2005; German 2009a).

Perhaps the most informative biochemical data gathered in this study are the patterns of digestive enzyme activities along the fishes’ intestines. A common pattern in lower termites, which digest cellulose in their hindgut via an endosymbiotic microbial community, is increasing cellulase activities in the hindgut region (Nakashima et al. 2002; Mo et al. 2004). Similarly, marine herbivorous fishes with active hindgut microbial populations have increasing exogenously produced enzyme activities (e.g., carrageenase) in the microbial extracts of their hindguts (Skea et al. 2005). However, none of the catfish species showed increasing cellulase activity in the distal intestine and, instead, showed no pattern (no increase or decrease; P. cf. n. “Marañon” and P. nocturnus) or decreasing activity (Pt. disjunctivus and H. pyrineusi) toward the distal intestine. Moreover, the cellulase activities in the catfish guts were five orders of magnitude lower than amylolytic activities, and one to two orders lower than laminarinase activities. Thus, the fish clearly digest soluble polysaccharides, like starch and laminarin, more rapidly than refractory polysaccharides, especially given the rapid transit time of food through the gut (German 2009b).

Decaying wood in an aquatic environment will likely have more nutritious dietary items collecting on the surface of the wood, and in spaces among fibers, than the wood itself. The epilithic algal complex (EAC), which is a loose assemblage of bacteria, cyanobacteria, filamentous green algae, diatoms, and detritus that grows on hard substrates in aquatic systems (Hoagland et al. 1982; van Dam et al. 2002; Wilson et al. 2003; Klock et al. 2007; German et al. 2009) contains soluble polysaccharides in the algae (including diatoms; Painter 1983) and in exopolymeric substances produced by microbes (Leppard 1995; Wotton 2004; Klock et al. 2007). These soluble polysaccharides are likely an important energy source, not only to grazing species like Pt. disjunctivus, but also to the “xylivorous” species digging into the decaying wood. Other EAC-consuming fishes (e.g., species in the genus Campostoma) have very similar patterns and magnitudes of amylolytic and laminarinase activities to the catfishes (German 2009a; German et al. 2009), suggesting that they target similar suites of nutrients from their foods.

The xylanase activities in P. nocturnus were the only luminal enzyme activities to be different between the intestinal fluid and the microbial extract, and the activities of this enzyme slightly increased, albeit not significantly so, toward the distal intestine of this species. Xylan is a component of hemicellulose (Petterson 1984; Breznak and Brune 1994), but mammals (and probably vertebrates in general) are not known to possess an endogenous xylanase or be able to metabolize the monomer of xylan, xylose, without the aid of intestinal microorganisms (Johnson et al. 2006a, b). Additionally, the catfish species examined in this study lacked β-xylosidase activity in their gut walls and had low β-xylosidase activities in their microbial extracts, which decreased distally in the digestive tract.

Given the low and variable cellulase and xylanase activities observed in the catfish, and the lack of any consistent pattern of activity along the guts of the fish, these enzymes are likely ingested (and produced by microbes ingested) with detritus rather than produced by a resident endosymbiotic community. This stands in contrast to the conclusions of Nelson et al. (1999), who isolated microbes with cellulolytic capabilities from the guts of loricariid catfishes, suggesting that there was a resident microflora in the fishes’ GI tracts. However, this does not mean that those microorganisms are endosymbionts digesting wood (Prejs and Blaszczyk 1977; Lindsay and Harris 1980). For example, grass carp, which eats aquatic macrophytes rich in cellulose and have cellulase activities in their GI tracts (Lesel et al. 1986; Das and Tripathy 1991), poorly digests the cellulose component of their plant diet (Van Dyke and Sutton 1977). This poor cellulose digestibility is likely due to rapid gut transit and low levels of microbial fermentation in the grass carp guts (Stevens and Hume 1998). Additionally, Prejs and Blaszczyk (1977) observed elevated cellulase activities in grass carp consuming detritus (i.e., degraded plant material), and little to no activity in fishes that had eaten fresh, non-degraded plant material, suggesting that the cellulase activities were produced by the microbial community on the detritus rather than by an endosymbiotic community in the grass carp GI tracts. Nevertheless, microbes can be cultured from the guts of grass carp (Trust et al. 1979; Lesel et al. 1986), but these microorganisms do not appear to be significantly involved in cellulose digestion. Similarly, our data on wild-caught wood-eating catfishes appear to be more indicative of ingested cellulases and xylanases than those of a resident endosymbiotic community. This is especially true in Pt. disjunctivus and H. pyrineusi, which showed decreasing cellulase and xylanase activities distally in their intestines. Furthermore, cellulase and xylanase activities were not higher in the xylivorous catfish species. For example, detritivorous Pt. disjunctivus possessed the highest cellulase activity in its proximal intestine, and xylivorous P. nocturnus the lowest (German 2008).

The cellulase activities measured in this study are three orders of magnitude lower than those reported for Panaque maccus and Pterygoplichthys sp. by Nelson et al. (1999). However, there are several methodological differences between this study and that performed by Nelson et al. First, they used assay conditions designed for ruminant mammals (pH 5, 40°C), which differ from the conditions in the fishes’ guts. We designed our assay conditions to reflect the fishes’ gut pH (pH 7.5; Table S1) and ambient temperatures of their environment (25°C). Second, Nelson et al. (1999) did not specify in which region of the gut they measured the enzyme activities. Third, when performing a general reducing sugar assay for polysaccharidase activity that includes intestinal contents (as was done by Nelson et al. and in this study), it is essential to perform appropriate blanks to account for background reducing sugars in the gut, and also for additional substrate that may be a source of other reducing sugars released during the assay (Skea et al. 2005; German et al. 2009). Not doing so will result in an over-estimation of activity levels; Nelson et al. did not perform this type of blank with their assays. Fourth, the activities were likely calculated differently between the two studies. Thus, direct comparisons of enzymatic activity levels between this study and that of Nelson et al. (1999) are impossible.

The most striking digestive enzyme activity data suggesting that the catfishes digest mainly soluble components from their detrital diet comes from the disaccharidase activities. The Michaelis–Menten constants (K m) for β-glucosidase in the gut walls of the fishes were an order of magnitude lower than those of the microbial extracts (Table 3). Although the β-glucosidase activities were higher in the microbial extracts than in the gut walls of the proximal intestines of P. cf. n. “Marañon”, P. nocturnus, and Pt. disjunctivus, this may be outweighed by the more efficient (lower K m) gut wall β-glucosidase of the fish. Hypostomus pyrineusi had the double effect of lower K m and higher activity of β-glucosidase in its proximal intestine gut wall. These results are important because microbes degrading the cellulose of wood in the river excrete enzymes extracellularly (Sinsabaugh et al. 1991, 1992; Tank et al. 1998; Hendel and Marxsen 2000) and depend on di- and monosaccharides [such as cellobiose (a β-glucoside) and glucose, respectively] to diffuse back to them so that they can then further digest and assimilate (Allison and Jastrow 2006) the cellulose. The fishes consume wood detritus that is in this process of degradation and, thus, there are likely many soluble components, such as cellobiose, in the decaying wood. Because the fishes’ β-glucosidases are more efficient than those produced by the microbes degrading the wood, the fish quickly digest and assimilate the cellobiose in their detrital diet. Additionally, because microbes in the environment secrete digestive enzymes extracellularly, the enzymes themselves are also likely on the detritus (Sinsabaugh et al. 1991, 1992; Tank et al. 1998; Hendel and Marxsen 2000), as occurs in soils (Allison 2006; Allison and Jastrow 2006), and are thus digested within the guts of the fish. This may explain why the microbial extract enzyme activities, almost without exception (Tables S2, S3; Figs. 3, 4), decreased distally in the intestines of the fish. This is especially true for β-glucosidase and stands in contrast with lower termites, which exhibit increasing β-glucosidase activities in their hindguts (McEwen et al. 1980). Detritivorous fishes, however, decrease β-glucosidase activity in their distal intestines (Smoot and Findlay 2000).

The more efficient and higher N-acetyl-β-d-glucosaminidase (NAG) activity in the fish gut walls may indicate that chitin, and its degradation products (i.e., chitobiose), are important energy and nitrogen sources to the fish. Fungi, which make cell walls of chitin, are some of the most active microorganisms in wood degradation and digestion (Swift et al. 1979; Breznak and Brune 1994; Hendel and Marxsen 2000), and are likely consumed by the fish with wood detritus. We attempted to measure chitinase activity in the guts of the catfishes, but there was so much background N-acetyl-glucosamine, which is the monomer of chitin and the endpoint of chitin digestion, in the fishes’ guts (>1 mM) that the determination of chitinase activity was impossible using colorimetric methods. This stands in contrast to other fishes that consume chitinous arthropods, in which chitinase activity was readily measured (Gutowska et al. 2004; German et al. 2009). N-acetyl-glucosamine is a usable energy source for vertebrate animals (Gutowska et al. 2004), and the presence of such large amounts of this compound in the intestines of the fish suggests that chitin digestion proceeds rapidly and, thus, fungi may be an important dietary item of the fishes. Indeed, microbes in general may be an important nutrient source to the catfishes, which would make lysozyme an important enzyme for nutrient acquisition in these animals (Krogdahl et al. 2005; Karasov and Martínez del Rio 2007). Lysozyme is important not only in bacterial cell wall degradation, but also for the degradation of chitin (Marsh et al. 2001; Krogdahl et al. 2005) in fungal cell walls. Thus, future studies of digestion in loricariids should take lysozyme activity into account and should explore non-colorimetric methods for the determination of chitinase activity (e.g., release of 14C; Marsh et al. 2001; fluorometric substrates; Allison et al. 2009).

Most of the catfish species showed significantly higher β-mannosidase activities in their gut walls than in the microbial extracts in all regions of the intestine (Table S3). It is difficult to speculate what these activities mean for the fish. Most analyses of mannan, the products of mannan degradation, and the enzymes involved in mannan digestion, have been aimed at bacteria and fungi (Valaskova and Baldrian 2006; Moreira and Filho 2008). Mannan and the monomer, mannose, are components of hemicelluloses in wood (Petterson 1984; Moreira and Filho 2008). The detectable activity of β-mannosidase in the gut walls of the fish suggest that, like β-glucosidase and cellobiose, the fish may be able to digest the soluble component of mannan degradation (β-mannosides). This may provide another example of how the fish efficiently assimilate soluble components of their detrital diet.

Many animals, including herbivorous and detritivorous fishes, feed to meet protein requirements (Bowen et al. 1995; Raubenheimer and Simpson 1998; Raubenheimer et al. 2005) and target protein from their food (Crossman et al. 2005). The increasing aminopeptidase activities in the distal intestines of the catfishes likely reflect increased efforts by the fish to absorb whatever protein is available in their detrital diet (Fraisse et al. 1981; Harpaz and Uni 1999; German 2009a), especially given the decreasing microvilli surface area of the distal intestine in these fishes (German 2009b). Furthermore, the trypsin activities in the loricariid catfishes are the highest we have measured in a number of fish taxa using identical methodology (German et al. 2004; Horn et al. 2006; German 2009a; German et al. 2009). The lipase activities of the fish followed the expected pattern for a pancreatic enzyme: decreasing activity distally in the intestine (German 2009a). However, Pt. disjunctivus increased its lipase activity distally in its intestine, perhaps as a lipid-scavenging mechanism.

In conclusion, loricariid catfishes in the genera Panaque and Hypostomus appear to be detritivores that specialize on a rather ubiquitous form of coarse detritus in their environment: degraded wood. The digestive tracts of these fishes, and of a closely related non-wood-eating detritivore, Pt. disjunctivus, are clearly geared for the consumption of large amounts of low-quality food and rapid transit of this food through the gut. A detrital diet can vary widely in protein, energy, and organic content (Bowen et al. 1995; Wilson et al. 2003; Crossman et al. 2005; German 2009b), and amorphous detritus can contain considerably more ash (up to 95%; Wilson et al. 2003; Crossman et al. 2005) than a woody diet (3%; German 2009b). Thus, although the wood-eating catfishes feed on woody detritus, they consume more organic matter on a proportional basis than fishes such as Pt. disjunctivus, which consume more amorphic detritus (German 2009b). Nevertheless, the digestive enzyme activities in GI tracts of the loricariid catfishes suggest that these fish hydrolyze soluble components of ingested food more efficiently than structural polysaccharides, and the majority of this hydrolysis takes place in the proximal and mid-intestine.

These patterns match well with the higher microvilli surface area (German 2009b) and soluble oligosaccharide profiles in these regions of the gut. Additionally, though the guts of the catfishes are highly reductive and hospitable to anaerobic microbes, the low SCFA concentrations throughout the fishes’ intestines show that they do not rely on microbial symbionts to digest structural polysaccharides via fermentative pathways. Further investigations in these fishes should emphasize their ability to digest bacteria and fungi found in detritus.

The inferential nature of this paper, although bolstered by our other investigations (German 2009b), including stable isotopic evidence that the fishes’ protein must be coming from non-woody sources (German 2008), leads to a call for more definitive evidence that these fishes make a living on soluble degradation products found in detritus. More quantitative tracer techniques, such as quantum dots (Whiteside et al. 2009) bound to specific compounds (e.g., cellulose vs. β-glucosides), can provide direct evidence of the assimilation of certain compounds and not of others. Either way, loricariid catfishes are abundant in the Amazonian basin, and the wood-eating species likely contribute to nutrient cycling in these habitats by reducing the particle size of wood from coarse debris to particles on the scale of 1 mm in diameter (German 2009b).

References

Adachi S (1965) Thin-layer chromatography of carbohydrates in the presence of bisulfite. J Chromatogr 17:295–299

Allison S (2006) Soil minerals and humic acids alter enzyme stability: implications for ecosystem processes. Biogeochem 81:361–373

Allison S, Jastrow J (2006) Activities of extracellular enzymes in physically isolated fractions of restored grassland soils. Soil Biol Biochem 38:3245–3256

Allison S, LeBauer D, Ofrecio M, Reyes R, Ta A, Tran T (2009) Low levels of nitrogen addition stimulate decomposition by boreal forest fungi. Soil Biol Biochem 41:293–302

Araujo-Lima C, Forsberg B, Victoria R, Martinelli L (1986) Energy sources for detritivorous fishes in the Amazon. Science 234:1256–1258

Armbruster J (1998) Modifications of the digestive tract for holding air in loricariid and scoloplacid catfishes. Copeia 1998:663–675

Armbruster J (2003) The species of the Hypostomus cochliodon group (Siluriformes: Loricariidae)—Zootaxa 249. Magnolia Press, Auckland

Armbruster J (2004) Phylogenetic relationships of the suckermouth armoured catfishes (Loricariidae) with emphasis on the Hypostominae and the Ancistrinae. Zool J Linnean Soc 141:1–80

Bergman E (1990) Energy contributions of volatile fatty acids from the gastrointestinal tract in various species. Physiol Rev 70:567–590

Bowen SH, Lutz EV, Ahlgren MO (1995) Dietary protein and energy as determinants of food quality: trophic strategies compared. Ecology 76:899–907

Breznak J, Brune A (1994) Role of microorganisms in the digestion of lignocellulose by termites. Annu Rev Entomol 39:453–487

Choat JH, Clements KD (1998) Vertebrate herbivores in marine and terrestrial environments: a nutritional ecology perspective. Annu Rev Ecol Syst 29:375–403

Clements KD, Raubenheimer D (2006) Feeding and nutrition. In: Evans DH (ed) The physiology of fishes. CRC Press, Boca Raton, pp 47–82

Clements KD, Gleeson V, Slaytor M (1994) Short-chain fatty acid metabolism in temperate marine herbivorous fish. J Comp Physiol B 164:372–377

Crossman DJ, Choat JH, Clements KD (2005) Nutritional ecology of nominally herbivorous fishes on coral reefs. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 296:129–142

Dahlqvist A (1968) Assay of intestinal disacharidases. Anal Biochem 22:99–107

Das KM, Tripathy SD (1991) Studies on the digestive enzymes of grass carp, Ctenopharyngodon idella (Val.). Aquacult 92:21–32

de Melo CE, de Arruda Machado F, Pinto-Silva V (2004) Feeding habits of fish from a stream in the savanna of central Brazil, Araguaia Basin. Neotrop Ichthyol 2:37–44

Delariva R, Agostinho A (2001) Relationship between morphology and diets of six neotropical loricariids. J Fish Biol 58:832–847

Erlanger BF, Kokowsky N, Cohen W (1961) The preparation and properties of two new chromogenic substrates of trypsin. Arch Biochem Biophys 95:271–278

Felicetti L, Shipley L, Witmer G, Robbins CT (2000) Digestibility, nitrogen excretion, and mean retention time by North American porcupines (Erethizon dorsatum) consuming natural forages. Physiol Biochem Zool 73:772–780

Fraisse M, Woo NYS, Noaillac-Depeyre J, Murat JC (1981) Distribution pattern of digestive enzyme activities in intestine of the catfish (Ameiurus nebulosus L.) and of the carp (Cyprinus carpio L.). Comp Biochem Phys 70A:443–446

Gawlicka A, Parent B, Horn MH, Ross N, Opstad I, Torrissen OJ (2000) Activity of digestive enzymes in yolk-sac larvae of Atlantic halibut (Hippoglossus hippoglossus): indication of readiness for first feeding. Aquaculture 184:303–314

German DP (2008) Beavers of the fish world: can wood-eating catfishes actually digest wood? A nutritional physiology approach. PhD Dissertation. Zoology, University of Florida, Gainesville, FL, USA

German DP (2009a) Do herbivorous minnows have “plug-flow reactor” guts? Evidence from digestive enzyme activities, gastrointestinal fermentation, and luminal nutrient concentrations. J Comp Physiol B. doi: 10.1007/s00360-009-0359-z

German DP (2009b) Inside the guts of wood-eating catfishes: can they digest wood? J Comp Physiol B. doi:10.1007/s00360-009-0381-z

German DP, Horn MH, Gawlicka A (2004) Digestive enzyme activities in herbivorous and carnivorous prickleback fishes (Teleostei: Stichaeidae): ontogenetic, dietary, and phylogenetic effects. Physiol Biochem Zool 77:789–804

German DP, Nagle BC, Villeda JM, Ruiz AM, Thomson AW, Contreras-Balderas S, Evans DH (2009) Evolution of herbivory in a carnivorous clade of minnows (Teleostei: Cyprinidae): effects on gut size and digestive physiology. Physiol Biochem Zool (in press)

Graham J, Baird T (1982) The transition to air breathing in fishes. 1: environmental effects on the facultative air breathing of Ancistrus chagresi and Hypostomus plecostomus (Loricariidae). J Exp Biol 96:53–67

Gutowska M, Drazen J, Robison B (2004) Digestive chitinolytic activity in marine fishes of Monterey Bay, California. Comp Biochem Physiol A 139:351–358

Harpaz S, Uni Z (1999) Activity of intestinal mucosal brush border membrane enzymes in relation to the feeding habits of three aquaculture fish species. Comp Biochem Physiol A 124:155–160

Hendel B, Marxsen J (2000) Extracellular enzyme activity associated with degradation of beech wood in a central European stream. Int Rev Hydrobiol 85:95–105

Hoagland K, Roemer S, Rosowski J (1982) Colonization and community structure of two periphyton assemblages, with emphasis on the diatoms (Bacillariophyceae). Am J Bot 69:188–213

Horn MH, Messer KS (1992) Fish guts as chemical reactors: a model for the alimentary canals of marine herbivorous fishes. Mar Biol 113:527–535

Horn MH, Gawlicka A, German DP, Logothetis EA, Cavanagh JW, Boyle KS (2006) Structure and function of the stomachless digestive system in three related species of New World silverside fishes (Atherinopsidae) representing herbivory, omnivory, and carnivory. Mar Biol 149:1237–1245

Iijima N, Tanaka S, Ota Y (1998) Purification and characterization of bile salt-activated lipase from the hepatopancreas of red seabream, Pagrus major. Fish Physiol Biochem 18:59–69

Johnson S, Jackson S, Abratt V, Wolfaardt V, Cordero-Otero R, Nicolson S (2006a) Xylose utilization and short-chain fatty acid production by selected components of the intestinal microflora of a rodent pollinator (Aethomys namaquensis). J Comp Physiol B 176:631–641

Johnson S, Nicolson S, Jackson S (2006b) Nectar xylose metabolism in a rodent pollinator (Aethomys namaquensis): defining the role of gastrointestinal microflora using 14C-labeled xylose. Physiol Biochem Zool 79:159–168

Jumars PA (2000) Animal guts as ideal chemical reactors: maximizing absorption rates. Am Nat 155:527–543

Kappler A, Brune A (2002) Dynamics of redox potential and changes in redox state of iron and humic acids during gut passage in soil feeding termites (Cubitermes spp.). Soil Biol Biochem 34:221–227

Karasov WH, Martínez del Rio C (2007) Physiological ecology: how animals process energy, nutrients, and toxins. Princeton University Press, Princeton

Klock JH, Wieland A, Seifert R, Michaelis W (2007) Extracellular polymeric substances (EPS) from cyanobacterial mats: characterisation and isolation method optimisation. Mar Biol 152:1077–1085

Krogdahl Å, Hemre GI, Mommsen T (2005) Carbohydrates in fish nutrition: digestion and absorption in postlarval stages. Aquacult Nutr 11:103–122

Leppard GG (1995) The characterization of algal and microbial mucilages and their aggregates in aquatic ecosystems. Sci Total Environ 165:103–131

Lesel R, Fromageot C, Lesel M (1986) Cellulose digestibility in grass carp, Ctenopharyngodon idella and in goldfish, Carassius auratus. Aquaculture 54:11–17

Levey DJ, Place AR, Rey PJ, Martínez del Rio C (1999) An experimental test of dietary enzyme modulation in pine warblers Dendroica pinus. Physiol Biochem Zool 72:576–587

Lindsay GJH, Harris JE (1980) Carboxymethylcellulase activity in the digestive tracts of fish. J Fish Biol 16:219–233

Lujan NK (2009) Jaw morpho-functional diversity, trophic ecology, and historical biogeography of the neotropical suckermouth armored catfishes (Siluriformes, Loricariidae). PhD Dissertation. Biological Sciences, Auburn University, Auburn, AL, USA

Marsh RS, Moeb C, Lomneth RB, Fawcetta JD, Place AR (2001) Characterization of gastrointestinal chitinase in the lizard Sceloporus undulatus garmani (Reptilia: Phrynosomatidae). Comp Biochem Physiol B 128:675–682

Martínez Del Rio C, Brugger KE, Rios JL, Vergara ME, Witmer MC (1995) An experimental and comparative study of dietary modulation of intestinal enzymes in the European starling (Sturnus vulgaris). Physiol Zool 68:490–511

McEwen S, Slaytor M, O’Brien R (1980) Cellobiase activity in three species of Australian termites. Insect Biochem 10:563–567

Miranda-Ribeiro A (1920) Peixes (excl. Characinidae). A: Commissão de Linhas Telegraphicas Estrategicas de Matto-Grosso ao Amazonas. Historia Natural Zoologia. Peixes Matto-Grosso Numero 58 (Annexo 5): 1–15

Mo J, Yang T, Song X, Chang J (2004) Cellulase activity in five species of important termites in China. Appl Entomol Zool 39:635–641

Moreira L, Filho E (2008) An overview of mannan structure and mannan-degrading enzyme systems. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 79:165–178

Mountfort D, Campbell J, Clements KD (2002) Hindgut fermentation in three species of marine herbivorous fish. Appl Environ Microbiol 68:1374–1380

Nakashima A, Watanabe H, Saitoh H, Tokuda G, Azuma JI (2002) Dual cellulose-digesting system of the wood-feeding termite, Coptotermes formosanus Shiraki. Insect Biochem Mol Biol 32:777–784

Nelson N (1944) A photometric adaptation of the Somogyi method for the determination of glucose. J Biol Chem 153:375–380

Nelson JA, Wubah D, Whitmer M, Johnson E, Stewart D (1999) Wood-eating catfishes of the genus Panaque: gut microflora and cellulolytic enzyme activities. J Fish Biol 54:1069–1082

Nico LG (2005) Changes in the fish fauna of the Kissimmee River basin, penninsular Florida: non-native additions. In: Rinne JN, Hughes RM, Calamusso B (eds) Historical changes in large river fish assemblages of the Americas. American Fisheries Society, Bethesda, pp 523–556

Nico LG, Jelks HL, Tuten T (2009) Non-native suckermouth armored catfishes in Florida: description of nest burrows and burrow colonies with assessment of shoreline conditions. Aquat Nuis Spec Res Progr Bull 09-1:1–30

Novakowski GC, Hahn NS, Fugi R (2008) Diet seasonality and food overlap of the fish assemblage in a pantanal pond. Neotrop Ichthyol 6:567–576

Painter TJ (1983) Algal polysaccharides. In: Aspinall GO (ed) The polysaccharides, vol 2. Academic Press, New York, pp 196–285

Petterson R (1984) The chemical composition of wood. In: Rowell R (ed) The chemistry of solid wood, advances in chemistry series 207. American Chemical Society, Washington, DC, pp 58–126

Potts RC, Hewitt PH (1973) The distribution of intestinal bacteria and cellulase activity in the harvester termite Trinervitermes trinervoides (Nasutitermitinae). Insect Soc 20:215–220

Pouilly M, Lino F, Bretenoux J, Rosales C (2003) Dietary–morphological relationships in a fish assemblage of the Bolivian Amazonian floodplain. J Fish Biol 62:1137–1158

Preiser H, Schmitz J, Maestracci D, Crane RK (1975) Modification of an assay for trypsin and its application for the estimation of enteropeptidase. Clin Chim Acta 59:169–175

Prejs A, Blaszczyk M (1977) Relationships between food and cellulase activity in freshwater fishes. J Fish Biol 11:447–452

Prins RA, Kreulen DA (1991) Comparative aspects of plant cell wall digestion in insects. Anim Feed Sci Technol 32:101–118

Pryor GS, Bjorndal K (2005) Symbiotic fermentation, digesta passage, and gastrointestinal morphology in bullfrog tadpoles (Rana catesbeiana). Physiol Biochem Zool 78:201–215

Pryor GS, German DP, Bjorndal K (2006) Gastrointestinal Fermentation in Greater Sirens (Siren lacertina). J Herpetol 40:112–117

Raubenheimer D, Simpson S (1998) Nutrient transfer functions: the site of integration between feeding behaviour and nutritional physiology. Chemoecol 8:61–68

Raubenheimer D, Zemke-White WL, Phillips RJ, Clements KD (2005) Algal macronutrients and food selectivity by the omnivorous marine fish Girella tricuspidata. Ecology 86:2601–2610

Roncari G, Zuber H (1969) Thermophilic aminopeptidases from Bacillus stearothermophilus. I: isolation, specificity, and general properties of the thermostable aminopeptidase I. Int J Protein Res 1:45–61

Schaefer S, Lauder GV (1986) Historical transformation of functional design: evolutionary morphology of feeding mechanisms in loricarioid catfishes. Syst Zool 35:489–508

Schaefer S, Stewart D (1993) Systematics of the Panaque dentex species group (Siluriformes: Loricariidae), wood-eating armored catfishes from tropical South America. Ichthyol Explor Freshwat 4:309–342

Sibly RM, Calow P (1986) Physiological ecology of animals, an evolutionary approach. Blackwell, Oxford

Sinsabaugh RL, Repert D, Weiland T, Golladay SW, Linkins AE (1991) Exoenzyme accumulation in epilithic biofilms. Hydrobiol 222:29–37

Sinsabaugh RL, Antibus RK, Linkins AE, McClaugherty CA, Rayburn L, Repert D, Weiland T (1992) Wood decomposition over a first-order watershed: mass loss as a function of lignocellulase activity. Soil Biol Biochem 24:743–749

Skea G, Mountfort D, Clements KD (2005) Gut carbohydrases from the New Zealand marine herbivorous fishes Kyphosus sydneyanus (Kyphosidae), Aplodactylus arctidens (Aplodactylidae), and Odax pullus (Labridae). Comp Biochem Physiol B 140:259–269

Skea G, Mountfort D, Clements KD (2007) Contrasting digestive strategies in four New Zealand herbivorous fishes as reflected by carbohydrase activity profiles. Comp Biochem Physiol B 146:63–70

Smith P, Krohn R, Hermanson G, Mallia A, Gartner F, Provenzano M, Fujimoto E, Goeke N, Olson B, Klenk D (1985) Measurement of protein using bicinchoninic acid. Anal Biochem 150:76–85

Smith T, Wahl D, Mackie R (1996) Volatile fatty acids and anaerobic fermentation in temperate piscivorous and omnivorous freshwater fish. J Fish Biol 48:829–841

Smoot JC, Findlay RH (2000) Digestive enzyme and gut surfactant activity of detrivorous gizzard shad (Dorosoma cepedianum). Can J Fish Aquat Sci 57:1113–1119

Somogyi M (1952) Notes on sugar determination. J Biol Chem 195:19–23

Stevens CE, Hume ID (1998) Contributions of microbes in vertebrate gastrointestinal tract to production and conservation of nutrients. Physiol Rev 78:393–427

Swift MJ, Heal OW, Anderson JM (1979) Decomposition in terrestrial ecosystems. University of California Press, Berkeley

Tank JL, Webster JR, Benfield EF, Sinsabaugh RL (1998) Effect of leaf litter exclusion on microbial enzyme activity associated with wood biofilms in streams. J N Am Bethol Soc 17:95–103

Trust T, Bull L, Currie B, Buckley J (1979) Obligate anaerobic bacteria in the gastrointestinal microflora of the grass carp (Ctenopharyngodon idella), Goldfish (Carassius auratus), and rainbow trout (Salmo gairdneri). J Fish Res Board Can 36:1174–1179

Valaskova V, Baldrian P (2006) Degradation of cellulose and hemicelluloses by the brown rot fungus Piptoporus betulinus—production of extracellular enzymes and characterization of the major cellulases. Microbiol SGM 152:3613–3622

van Dam A, Beveridge M, Azim M, Verdegem M (2002) The potential of fish production based on periphyton. Rev Fish Biol Fisheries 12:1–31

Van Dyke JM, Sutton DL (1977) Digestion of duckweed (Lemna spp.) by the grass carp (Ctenopharyngodon idella). J Fish Biol 11:273–278

Vispo C, Hume ID (1995) The digestive tract and digestive function in the North American porcupine and beaver. Can J Zool 73:967–974

Weber C (1991) Nouveaux taxa dans Pterygoplichthys sensu lato (Pisces, Siluriformes, Loricariidae). Revue Suisse de Zoologie 98: 637–643

Whiteside MD, Treseder KK, Atsatt PR (2009) The brighter side of soils: quantum dots track organic nitrogen through fungi and plants. Ecology 90:100–108

Wilson SK, Bellwood DR, Choat JH, Furnas MJ (2003) Detritus in the epilithic algal matrix and its use by coral reef fishes. Oceanogr Mar Biol Annu Rev 41:279–309

Wotton RS (2004) The ubiquity and many roles of exopolymers (EPS) in aquatic systems. Sci Mar 68(Suppl 1):13–21

Xie XL, Du J, Huang QS, Shi Y, Chen QX (2007) Inhibitory kinetics of bromacetic acid on β-N-acetyl-d-glucosaminidase from prawn (Penaeus vannamei). Int J Biol Macromol 41:308–313

Acknowledgments