Abstract

We investigate the relationship between social class belonging and contributions to local public goods. By utilizing the social class classifications in Colombia and an experimental design based on the strategy method, we can both study contributions to public goods and classify subjects into contribution types. We find similar contribution levels between high and medium-low social classes and also similar distributions of contributor types. However, low social class members conditionally contribute a significantly higher level than high social class members. This has implications for policymakers, who may need to consider differential policy schemes for locally provided public goods.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

It should be noted that in a multi-period public goods experiment, a selfish individual might contribute for strategic reasons just to encourage other group members to contribute.

By culture we mean classification of people which is not directly related to genetic inheritance; it can be both material as well as non-material such as beliefs and norms.

To explicitly test for the group effect, Gächter and Thöni (2005) created artificial groups within a culture in a public goods experiment. They conducted a two-stage public goods experiment where they first conducted a one-shot public goods experiment to identify types of contributors and then grouped subjects of similar contribution types together (and informed them about it) in a multi-period public goods experiment. They found that cooperative groups managed to maintain high levels of cooperation throughout the experiment and vice versa. Similar findings are reported in, e.g., Gunnthorsdottir et al. (2007), Ones and Putterman (2007), and Page et al. (2005).

The labeling “low-low” is a direct translation of the Spanish labeling “bajo-bajo.” Although this term would probably be better labeled as “very low” in English, we decided to keep the original Spanish labeling.

The exchange rate at the time of the experiment was approximately US$ 1 = COP 2000.

In cases where samples have different opportunity costs, either the absolute amount in the experiment or the opportunity cost can be kept constant. We decided to keep the opportunity cost constant; it should be noted that Kocher et al. (2008) did not find a significant stake effect using a one-shot public goods experiment. In our experiment, a lunch at the MEDIUM-LOW social-class university costs approximately 75 % of a lunch at the HIGH social-class university, and similar differences exist for other goods in the respective neighborhoods.

Both figures include a show-up fee of COP 5000.

When comparing material resources and subjective socio-economic status not using broad categories of social class (university) but instead by socio-economic strata, the results hold. This indicates that socio-economic stratification is a good proxy for social class.

In fact, the conditional contribution of participants from stratum 1 is higher than the average contribution from the other group members, i.e., it is above the perfect conditional contribution schedule.

At the MEDIUM-LOW social class university, 27 % of the participants perfectly match their unconditional contribution given their beliefs and their responses in in the conditional contribution table; the corresponding figure is 20 % for the HIGH social class university. Based on a test of proportions we cannot reject the hypothesis that they are the same (p value = 0.39).

The results hold when using socio-economic strata as an independent variable instead of a dummy variable for HIGH social class.

References

Adler NE, Epel ES, Castellazzo G, Ickovics JR (2000) Relationship of subjective and objective social status with psychological and physiological functioning: preliminary data in healthy, white women. Health Psychol 19:586–592

Anderson L, DiTraglia F, Gerlach J (2011) Measuring altruism in a public goods experiment: a comparison of U.S. and Czech subjects. Exp Econ 14:426–437

Anderson CM, Putterman L (2006) Do non-strategic sanctions obey the law of demand? The demand for punishment in the voluntary contribution mechanism. Games Econ Behav 54:1–24

Axelrod R (1984) The evolution of cooperation. Basic Books, New York

Baland JM, Platteau JP (1996) Halting degradation of natural resources: is there a role for rural communities?. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Rome

Bowlby J (1979) The making and breaking of affectional bonds. Tavistock, London

Brandts J, Saijo T, Schram AJHC (2004) A four-country comparison of spite and cooperation in public goods games. Public Choice 119:381–424

Buckley E, Croson R (2006) Income and wealth heterogeneity in the voluntary provision of linear public goods. J Public Econ 90:935–955

Burlando RM, Hey JD (1997) Do Anglo-Saxons free ride more? J Public Econ 64:41–60

Cárdenas J-C (2003) Real wealth and experimental cooperation: experiments in the field lab. J Dev Econ 70:263–289

Cárdenas JC (2011) Social norms and behavior in the local commons as seen through the lens of field experiments. Environ Resour Econ 48:451–485

Cárdenas J-C, Carpenter J (2008) Behavioural development economics: lessons from field labs in the developing world. J Dev Stud 44:337–364

Cárdenas J-C, Stranlund J, Willis C (2000) Local environmental control and institutional crowding-out. World Dev 28:1719–1733

Carpenter JP (2007) The demand for punishment. J Econ Behav Organ 62:522–542

Chan KS, Mestelman S, Moir R, Muller A (1996) The voluntary provision of public goods under varying income distributions. Can J Econ 29:54–69

Chaudhuri A (2011) Sustaining cooperation in laboratory public goods experiments: a selective survey of the literature. Exp Econ 14:47–83

Cherry TD, Kroll S, Shogren JF (2005) The impact of endowment heterogeneity and origin on public good contributions: evidence from the lab. J Econ Behav Organ 57:357–365

Drentea P (2000) Age, debt, and anxiety. J Health Soc Behav 41:437–450

Fehr E, Fischbacher U (2003) The nature of human altruism. Nature 425:785–791

Fehr E, Fischbacher U, Gächter S (2002) Strong reciprocity, human cooperation, and the enforcement of social norms. Hum Nature 13:1–25

Fehr E, Gächter S (2000) Cooperation and punishment in public goods experiments. Am Econ Rev 90:980–994

Fehr E, Gächter S (2002) Altruistic punishment in humans. Nature 415:137–140

Fischbacher U, Gächter S (2010) Social preferences, beliefs, and the dynamics of free riding in public good experiments. Am Econ Rev 100:541–556

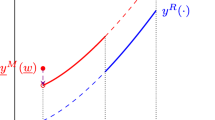

Fischbacher U, Gächter S, Fehr E (2001) Are people conditionally cooperative? Evidence from a public goods experiment. Econ Lett 71:397–404

Gardner A, West S (2004) Cooperation and punishment, especially in humans. Am Nat 164:753–764

Goergantzis N, Proestakis A (2011) Accounting for real wealth in heterogeneous-endowment public good games. ThE Papers 10/20, Department of Economic Theory and Economic History of the University of Granada

Gächter S (2007) Conditional cooperation: behavioural regularities from the lab and the field and their policy implications. In: Frey BS, Stuzter A (eds) Psychology and economics: a promising new cross-disciplinary field (Cesinfo seminar Series). MIT Press, Cambridge, pp 19–50

Gächter S, Herrmann B (2011) The limits of self-goverence when cooperators get punished: experimental evidence from urban and rural Russia. Eur Econ Rev 55:193–210

Gächter S, Renner E (2010) The effects of (Incentivized) belief elicitation in public goods experiments. Exp Econ 13:364–377

Gächter S, Thöni C (2005) Social learning and voluntary cooperation among like-minded people. J Eur Econ Assoc 3:303–314

Gächter S, Herrmann B, Thöni C (2010) Culture and cooperation. Philos Transit R Soc B Biol Sci 365:2651–2661

Gintis H (2000) Strong reciprocity and human sociality. J Theor Biol 206:169–179

Gunnthorsdottir A, Houser D, McCabe K (2007) Disposition, history and contributions in public goods experiments. J Econ Behav Organ 62:304–315

Hammerstein P (ed) (2003) Genetic and cultural evolution of cooperation. The MIT Press, Cambridge

Hardin G (1968) The tragedy of the commons. Science 162:1243–1248

Henrich J, Henrich N (2007) Why humans cooperate: a cultural and evolutionary explanation. Evolution and cognition series. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Herrmann B, Thöni C, Gächter S (2008) Antisocial punishment across societies. Science 319:1362–1367

Herrmann B, Thöni C (2009) Measuring conditional cooperation: a replication study in Russia. Exp Econ 12:87–92

Hofmeyr A, Burns J, Visser M (2007) Income inequality, reciprocity and public good provision: an experimental analysis. S Afr J Econ 75:508–520

Kocher M, Martinsson P, Visser M (2012) Social background, cooperative behavior, and norm enforcement. J Econ Behav Organ 81:341–354

Kocher M, Cherry T, Kroll S, Netzer R, Sutter M (2008) Conditional cooperation on three continents. Econ Lett 101:175–178

Kosfeld M, Heinrichs M, Zak PJ, Fischbacher U, Fehr E (2005) Oxytocin increases trust in humans. Nature 453:673–676

Kraus MW, Piff PK, D (2009) Social class, the sense of control, and social explanation. J Personal Soc Psychol 97:992–1004

Kraus MW, Horberg EJ, Goetz JL, Keltner D (2011) Social class rank, threat vigilance, and hostile reactivity. Personal Soc Psychol Bull 37:1376–1388

Kraus MW, Piff PK, Mendoza-Denton R, Rheinschmidt ML, Keltner D (2012) Social class, solipsism, and contextualism: how the rich are different from the poor. Psychol Rev 119:546–572

Lamba S, Mace R (2011) Demography and ecology drive variation in cooperation across human populations. Proc Natl Acad Sci 108:14426–14430

Ledyard JO (1995) Public goods: a survey of experimental research. In: Kagel J, Roth A (eds) The handbook of experimental economics. Princeton University Press, Princeton, pp 94–111

Maier-Rigaud F, Martinsson P, Staffiero G (2010) Ostracism and the provision of a public good: experimental evidence. J Econ Behav Organ 73:387–395

Martinsson P, Pham-Khanh N, Villegas-Palacio C (2013) Conditional cooperation and disclosure in developing countries. J Econ Psychol 34:148–155

Masclet D, Villeval MC (2008) Punishment, inequality and welfare: a public good experiment. Soc Choice Welf 31:475–502

National Department of Statistics of Colombia (2011a) Documento Conpes 3386: Focaliz Subsidious Servicios Publicos. National Department of Statistics of Colombia. http://www.dane.gov.co/files/dig/CONPES_3386_oct2005_Focaliz_subsidios_servicios_publicos.pdf. Accessed 01 Oct 2012

National Department of Statistics of Colombia (2011b) Database. http://www.dane.gov.co. Accessed 01 Oct 2012

Oakes JM, Rossi RH (2003) The measurement of SES in health research: current practice and steps toward a new approach. Soc Sci Med 56:769–784

Ones U, Putterman L (2007) The ecology of collective action: a public goods and sanctions experiment with controlled group formation. J Econ Behav Organ 62:495–521

Olson M (1965) The logic of collective action: public goods and the theory of groups. Harvard University Press, Boston

Ostrom E, Gardner R, Walker J (1992) Rules, game and common pool resources. The University of Michigan Press, Michigan

Ostrom E (1991) Governing the commons: the evolution of institutions for collective action. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Page T, Putterman L, Unel B (2005) Voluntary association in public goods experiments: reciprocity, mimicry, and efficiency. Econ J 115:1032–1052

Piff PK, Stancato DM, Côté S, Mendoza-Denton R, Keltner D (2012) Higher social class predicts increased unethical behavior. Proc Natl Acad Sci 109:4086–4091

Rico D (2005) Evaluación del costo de las matrículas en la Universidad Nacional de Colombia. Universidad Nacional De Colombia, mimeo, Sede Medellín, Oficina de Planeación

Rustagi D, Engel S, Kosfeld M (2010) Conditional cooperation and costly monitoring explain success in forest commons management. Science 330:961–965

Shogren JF (1990) On increased risk and voluntary provision of public goods. Soc Choice Welf 7:221–229

Snibbe AC, Markus HR (2005) You can’t always get what you want: educational attainment, agency, and choice. J Personal Soc Psychol 88:703–720

Sober E, Wilson DS (1998) Unto others. The evolution and psychology of unselfish behaviour. Harvard University Press, Cambridge

Taylor SE, Klein LC, Lewis BP, Gruenewald TL, Gurung RAR, Updegraff JA (2000) Biobehavioral responses to stress in females: tend-and-befriend, not fight-or-flight. Psychol Rev 107:411–429

Thöni C, Tyran J-R, Wengström E (2012) Microfoundations of social capital. J Public Econ 96:635–643

Zelmer J (2003) Linear public goods experiments: a meta-analysis. Exp Econ 6:299–310

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the financial support from the Swedish Research Council (Vetenskapsrådet), Formas through the program Human Cooperation to Manage Natural Resources (COMMONS), and the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (Sida) to the Environmental Economics Unit at the University of Gothenburg. We are also grateful to the School of Engineering (Escuela de Ingeniería de Antioquia), Medellín, Colombia, and Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Sede Medellín, for their support of our experiment. Special thanks go to Antonio Villegas-Rivera and Felipe Mejía for excellent research assistance, and to Martin Kocher, Marta Matute, Katarina Nordblom, Patrik Söderholm, Alba Upegui, managing editor Clemens Puppe, and two anonymous referees for their helpful comments.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Martinsson, P., Villegas-Palacio, C. & Wollbrant, C. Cooperation and social classes: evidence from Colombia. Soc Choice Welf 45, 829–848 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00355-015-0886-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00355-015-0886-3