Abstract

It has long been suggested that habitat structure affects how colonial birds are distributed within their nesting aggregations, but this hypothesis has never been formally tested. The aim of this study was to test for a correlated evolution between habitat heterogeneity and within-colony distributions of Ciconiiformes by using Pagel’s general method of comparative analysis for discrete variables. The analysis indicated that central-periphery gradients of distribution (high-quality individuals occupying central nesting locations) prevail in species breeding in homogeneous habitats. These were mainly ground-nesting larids and spheniscids, where clear central-periphery patterns were recorded in ca. 80 % of the taxa. Since homogeneous habitats provide little variation in the physical quality of nest sites, central nesting locations should be largely preferred because they give better protection against predators by means of more efficient predator detection and deterrence. By contrast, central-periphery gradients tended to be disrupted in heterogeneous habitats, where 75 % of colonial Ciconiiform species showed uniform patterns of distribution. Under this model of distribution, edge nest sites of high physical quality confer higher fitness benefits in comparison to low-quality central sites, and thus, high-quality pairs are likely to choose nest sites irrespectively of their within-colony location. Breeding in homogeneous habitats and uniform distribution patterns were identified as probable ancestral states in Ciconiiformes, but there was a significant transition rate from uniform to central-periphery distributions in species occupying homogeneous habitats.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

According to classic theoretical predictions on resource acquisition in animals, individuals should be distributed in environments so as to maximise their fitness. If there are no competitive asymmetries between conspecifics, the habitat should be occupied proportionally to the available resources under the assumptions of the ideal free distribution model of Fretwell and Lucas (1970), which implies that the density of individuals should increase along with the increasing quality of the habitat patch. However, in natural populations of animals, individuals only rarely gain equal access to resources, as they notably differ in their competitive abilities. Conforming to the empirical evidence on competitive asymmetries within populations, a model of ideal despotic distribution was proposed, assuming that dominant individuals have capacities to secure the best available territories and to relegate conspecifics of lower phenotypic quality to less attractive habitats (Fretwell 1972).

Although there is abundant empirical evidence for ideal despotic distributions in territorial birds (Andrén 1990; Ens et al. 1995; Møller 1995; Petit and Petit 1996), information on the patterns of distribution in colonial species are much more scarce. Distribution patterns of colonial birds are typically considered on at least three different levels: (1) distribution of colonies in the available environment; (2) distribution of individuals among colonies; and (3) distribution of individuals within colonies. Large-scale patterns of colony distribution as well as distribution of individuals among the colonies located in the habitat patches of different quality have both recently received increasing attention (Brown and Rannala 1995). It has been demonstrated that the foundation of new colonies in several avian species follows a despotic model (Serrano and Tella 2007; Oro 2008) and that individuals of low phenotypic quality (expressed by young age or poor physical quality) may be excluded from colonies that are located in the best habitat patches (Rendón et al. 2001).

By contrast, much less empirical data has been collected on the distribution of individuals within their breeding colonies. Despite this relative scarcity of information, it seems safe to distinguish two major components of nesting site attractiveness that may have important fitness consequences for colonially breeding species and that, consequently, are likely to determine within-colony distribution patterns. The first of the components is associated with the within-colony location of nest sites, as it is generally accepted that the centres of colonies offer the highest benefits in terms of fitness (Coulson 1968; Aebischer and Coulson 1990). It has been commonly reported that pairs nesting in the centres are likely to achieve higher breeding success due to decreased predation-related losses of eggs and chicks (Götmark and Andersson 1984; Yorio and Quintana 1997; Minias and Kaczmarek 2013), thus indicating that colonies may act as selfish herds against predation (Brown and Brown 2001). The mechanisms explaining lower susceptibility of central pairs to predation may include more efficient detection and deterrence of predators in the central parts of colonies. Central nests are also likely to be less accessible to predators, although this may largely depend on the type of predator (Brunton 1997). However, in general, there is large empirical support that colonial birds dilute the risk of predation (Brown and Brown 2001) and that central nesting sites are by far the most efficiently protected sites against predators. Although the breeding success of centrally nesting pairs may be decreased due to density-dependent intraspecific interactions (Jovani and Grimm 2008; Ashbrook et al. 2010) and parasitic rates (Tella 2002), many studies have demonstrated higher reproductive output in colony centres in comparison to the edges (Patterson 1965; Gochfeld 1980; Becker 1995; Vergara and Aguirre 2006). For this reason individuals of higher quality are likely to occupy the best central sites and to relegate individuals of lower quality to less attractive edge sites. Assuming such a despotic mechanism of colony formation, one would expect a central-periphery pattern of distribution where the phenotypic quality of breeding birds declines from the centre towards the edges of a colony (Coulson 1968).

The physical quality of nesting sites may be considered as the second major component of their attractiveness for colonial birds. If the habitat is heterogeneous on a small spatial scale, considerable variation in the physical quality of nesting sites within colonies is expected. Under this assumption, nest sites of high quality would be likely to provide much more effective protection against predators or adverse weather conditions and thus would promote higher reproductive success. It has been suggested that if the fitness benefits of nesting in sites of good physical quality considerably exceeds benefits associated with the central nesting position, then high-quality pairs may choose the best available nesting sites independently of their location in a colony (Velando and Freire 2001). Under such circumstances, the central-periphery patterns could be disrupted and pairs of varying quality could be distributed more or less uniformly among the central and peripheral zones of colonies.

Although the effects of habitat heterogeneity on the within-colony patterns of distribution in birds have long been hypothesised, most of the empirical evidence has only been circumstantial and the suggested relationship has never been supported by a formal analysis. The aim of this study was to test for evolutionary correlations between the structure of breeding habitat and within-colony distributions in Ciconiiformes (sensu Sibley and Ahlquist 1990), a phylogenetic group with the highest prevalence of coloniality among birds (Siegel-Causey and Kharitonov 1990). According to the theoretical predictions, I expected that birds nesting in homogeneous habitats should form colonies according to the central-periphery model of distribution, whereas in heterogeneous habitats, the central-periphery gradients should be disrupted (uniform model of distribution).

Methods

For the purpose of the analysis, I collected data from the literature for 34 colonial species of Ciconiiformes grouped into nine families (Table 1). Each species was assigned a prevailing model of within-colony distribution: central-periphery or uniform. The central-periphery model was assigned when all studied reproductive parameters or parental quality traits declined from the centre of the colony towards the peripheries. In contrast, the uniform model corresponded to a situation in which the central-periphery gradients were disrupted, at least with respect to some of the studied traits or in some of the studied colonies. With such an approach, the distribution patterns could be coded binarily, with central-periphery distributions denoted as 0 and distributions in which central-periphery gradients were disrupted (uniform models) denoted as 1. Heterogeneity of the breeding habitat was also treated as a categorical variable with two states. Bare ground and mats of floating vegetation were identified as homogeneous habitats, as these provide none or negligible variation in the physical quality of nesting sites and all nests are more or less equally vulnerable to predators or adverse weather conditions (denoted as 0). All of the other habitats that may provide moderate or considerable variation in the physical quality of nesting sites were considered to be heterogeneous habitats (denoted as 1). This category mostly included rocky habitats (cliff ledges, rocky slopes and islets, rock crevices, hollows and burrows) and vegetated habitats (woodlands and shrubs).

Since data from different species are not independent due to their shared ancestral states, it is widely acknowledged that comparative analyses must control for the phylogeny. I based my phylogenetic tree on the classification of Sibley and Ahlquist (1990). This phylogeny is uniquely available for the entire order of Ciconiiformes, and for this reason, it was used to branch the families of my tree (Fig. 1). Although the phylogeny of Sibley and Ahlquist (1990) was once considered controversial (Sheldon and Gill 1996), it is now assumed as quite robust for phylogenetic analyses in birds (reviewed in Mooers and Cotgreave 1994), and hence, it has been broadly used in comparative studies (Cézilly et al. 2000; Dubois and Cézilly 2002; Garamszegi et al. 2005; Olson et al. 2008), including those on avian coloniality (Rolland et al. 1998; Varela et al. 2007). In order to branch the genera and species, I used five phylogenies based on both molecular and morphological data (Sheldon 1987; Kennedy et al. 2000; Thomas et al. 2004; Bertelli and Giannini 2005; Smith 2010). Since different approaches were used to construct the above phylogenies, I decided not to control for branch lengths, which followed from other comparative studies (Dubois et al. 1998; Rolland et al. 1998; Cézilly et al. 2000; Varela et al. 2007). Setting equal branch lengths is considered conservative (Pagel 1994), and it has been demonstrated that it does not bias the results qualitatively (Møller et al. 1998; Nunn 1999).

To test for a correlated evolution between breeding habitat structure and within-colony distribution patterns, I used Pagel’s discrete variable method (1994) which uses the continuous-time Markov model in order to characterise evolutionary changes in selected pairs of variables along each branch of the phylogenetic tree. The method compares the fit of two different models assuming an either independent or dependent (the rate of change of one trait depends on the background state of the other) evolution of traits. The models were fitted using maximum likelihood and compared using the likelihood ratio (LR) statistic, which is expressed as LR = 2 (logL (D) − logL (I)), where L (D) is the likelihood of the model that allows the traits to evolve in a correlated fashion and L (I) is the likelihood of the independent model. The LR statistic is asymptotically distributed as χ 2 with four degrees of freedom for this test (Pagel 1997).

The discrete variables method was also used to estimate the ordering and direction of the evolutionary changes of the two analysed variables (so-called temporal order tests). For this purpose, one needs to fit reduced models in which a certain rate of evolutionary transition q ij is excluded a priori (set to 0). The constrained seven-parameter models are then compared to the full eight-parameter model which tests the hypotheses whether the specified transition rates differ significantly from zero. The tests are asymptotically distributed as χ 2 with one degree of freedom (Pagel 1994). In this manner, the evolution between the ancestral states and the derived states of both selected variables may be traced. For root reconstruction of ancestral states, I used the maximum-likelihood reconstruction method of Pagel (1999). All analyses were performed with BayesTraits (Pagel and Meade 2008).

Results

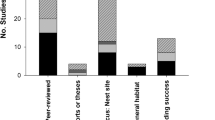

Among the 34 taxa used for the analysis, there were 20 species that nested in homogeneous habitats (59 %) and 14 that chose heterogeneous habitats for breeding (41 %). A similar proportion was found between the number of species that exhibited central-periphery distribution within colonies and those in which central-periphery gradients were disrupted (56 vs. 44 %, Table 1). There was a clear tendency for species breeding in homogeneous habitats to be distributed central-peripherally within the colonies (Fig. 2). The log-likelihood of the model of independent evolution was estimated at L 0 = −36.10 and was significantly lower in comparison to the likelihood of the dependent model L 1 = −30.18 (χ 2 = 11.83, df = 4, P = 0.019). Such results support the hypothesis of a correlated evolution between preferences for heterogeneous breeding habitats and uniform patterns of within-colony distribution.

Breeding in homogeneous habitats and uniform distribution of pairs within colonies were identified as ancestral states with a probability of 94.8 %. I found a significant rate of transition from uniform to central-periphery distribution in species that bred in homogeneous habitats (χ 2 = 4.54, df = 1, P = 0.033). I also found a significant rate of reversed transitions, i.e. from central-periphery to uniform patterns of distribution (χ 2 = 7.50, df = 1, P = 0.006). The rate of evolution from breeding in homogeneous to heterogeneous habitats with no change in the background state of uniform distribution pattern was not significant (χ 2 = 1.14, df = 1, P = 0.29), but it cannot be excluded that this could have resulted from the low power of the test. All the other transition rates were also non-significant (all P > 0.05).

Discussion

This study was the first to formally demonstrate a link between within-colony distribution patterns in birds and the structure of preferred nesting habitat by using comparative analysis. It was shown that as much as 85 % of colonial Ciconiiformes species which breed in homogeneous habitats tend to show clear central-periphery patterns of distribution within their colonies and that these are mostly ground-nesting species from the Spheniscidae and Laridae families. In general, bare-ground habitats, such as sandy islands or dunes, provide no apparent variation in the physical quality of the nesting sites. Under such conditions, each nest site is likely to be equally exposed to predation and inclement weather. Consequently, nest-site selection patterns should evolve towards choosing an appropriate location within the colony, where pressure coming from predators will be minimised. Assuming that all nest sites are physically similar, the highest fitness benefits are expected to be acquired via nesting in the central parts of colonies (Coulson 1968). As colony centres are usually associated with higher nesting densities, the mechanisms which may explain lower predation rates at these locations include: (1) restricted accessibility for predators (Siegel-Causey and Hunt 1981); (2) more efficient communal defence (Elliot 1985); (3) more efficient detection of predators (Roberts 1996); and (4) lower probability of being depredated due to the dilution effect (Murphy and Schauer 1996).

By contrast, heterogeneous habitats were found to disrupt the central-periphery patterns of distribution within colonies. In habitats of moderate or high heterogeneity, edge nest sites of high physical quality are likely to confer higher fitness benefits in comparison to low-quality central sites. Thus, high-quality pairs are expected to choose nest sites irrespectively of their within-colony location, and thus, they are expected to be uniformly distributed among the central and peripheral zones of colonies. Central-periphery distributions were found to be disrupted in nearly 75 % of colonial Ciconiiformes species that nested in heterogeneous habitats. It seems that uniform patterns of distribution are especially common in birds that establish colonies on cliffs or in other rocky habitats, including various Phalacrocoracidae and Sulidae species. Nesting sites such as crevices under fallen rocks, open ground caves and open ledges on cliffs usually show great variation in their physical quality and attractiveness for birds; for example, a clear preference for sites with more lateral and overhead cover, with better drainage and with better visibility has been demonstrated for the European Shag Phalacrocorax aristotelis (Velando and Freire 2003). Such physical characteristics of nesting sites have been shown to provide more effective protection against predators and to prevent broods from flooding, unfavourable atmospheric conditions and intra-specific inference, which greatly affected the hatching success of Shags (Velando and Freire 2003). The distribution of birds within the same colony of Shags did not conform to the assumptions of the central-periphery model, as individuals of different quality were distributed despotically among the sites of varying physical quality (Velando and Freire 2001, 2003).

Disruptions in the central-periphery patterns of distribution were also recorded in several waterbird species associated with woodland habitats; although, this kind of environment is expected to provide only moderate variation in the physical quality of nesting sites, most commonly expressed by variation in tree height and canopy structure. In several tree-nesting colonial avian species, tree height was identified as an important predictor of reproductive success and was suggested to determine accessibility of nests to ground and tree-dwelling predators (Post 1990; Childress and Bennun 2000). The breeding success of the Scarlet Ibis Eudocimus ruber correlated positively with nest cover by overhanging branches (Olmos 2003), and the study on Cattle Egrets Bubulcus ibis indicated higher fledging success in pairs nesting close to the trunks of trees (Si Bachir et al. 2008). However, in some cases, the fitness benefits that were associated with nesting in the sites of high physical quality could be acquired via mechanisms not related to anti-predatory protection; for example, in the tree-nesting subspecies of Great Cormorant Phalacrocorax carbo sinensis, the physical quality of nesting sites (tree height) determined the probability of nest collapse before the conclusion of breeding activities (Minias and Kaczmarek 2013).

References

Aebischer NJ, Coulson JC (1990) Survival of the kittiwake in relation to sex, year, breeding experience and position in the colony. J Anim Ecol 59:1063–1071

Andrén H (1990) Despotic distribution, unequal reproductive success, and population regulation in the jay Garrulus glandarius L. Ecology 71:1796–1803

Andrews DJ, Day KR (1999) Reproductive success in the Cormorant Phalacrocorax carbo carbo in relation to colony nest position and timing of nesting. Atl Seabirds 1:107–120

Antolos M, Roby DD, Lyons DE, Anderson SK, Collins K (2006) Effects of nest density, location and timing of breeding success of Caspian Terns. Waterbirds 29:465–472

Ashbrook K, Wanless S, Harris MP, Hamer KC (2010) Impacts of poor food availability on positive density dependence in a highly colonial seabird. Proc R Soc Lond B 277:2355–2360

Barbosa A, Moreno J, Potti J, Merino S (1997) Breeding group size, nest position and breeding success in the Chinstrap Penguin. Polar Biol 18:410–414

Becker PH (1995) Effects of coloniality on gull predation on Common Tern (Sterna hirundo) chicks. Colon Waterbirds 18:11–22

Bertelli S, Giannini NP (2005) A phylogeny of extant penguins (Aves: Sphenisciformes) combining morphology and mitochondrial sequences. Cladistics 21:209–239

Blus LJ, Keahey JA (1978) Variation in reproductive success with age in the Brown Pelican. Auk 95:128–134

Bried J, Jouventin P (2001) The King Penguin Aptenodytes patagonicus, a non-nesting bird which selects its breeding habitat. Ibis 143:670–673

Brown CR, Brown MB (2001) Avian coloniality: progress and problems. Curr Ornithol 16:1–82

Brown CR, Rannala B (1995) Colony choice in birds: models based on temporally invariant site quality. Behav Ecol Sociobiol 36:221–228

Brunton DH (1997) Impact of predators: center nests are less successful that edge nests in a large nesting colony of Least Terns. Condor 99:372–380

Buckley PA, Buckley FG (1977) Hexagonal packing of Royal Tern nests. Auk 94:36–43

Burger J, Shisler JK (1980) The process of colony formation among Herring Gulls Larus argentatus nesting in New Jersey. Ibis 122:15–26

Cézilly F, Dubois F, Pagel M (2000) Is mate fidelity related to site fidelity? A comparative analysis in Ciconiiformes. Anim Behav 59:1143–1152

Childress RB, Bennun LA (2000) Nest size and location in relation to reproductive success and breeding timing of tree-nesting Great Cormorants. Waterbirds 23:500–505

Côté SD (2000) Aggressiveness in King Penguins in relation to reproductive status and territory location. Anim Behav 59:813–821

Coulson JC (1968) Differences in the quality of birds nesting in the center and on the edges of a colony. Nature 217:478–479

Coulson JC, Wooller RD (1976) Differential survival rates among breeding Kittiwake gulls Rissa tridactyla. J Anim Ecol 45:205–213

Davis LS, McCaffrey FT (1986) Survival analysis of eggs and chicks of Adélie Penguins (Pygoscelis adeliae). Auk 103:379–388

Decamps S, Le Bohec C, Le Mahoy Y, Gendner J-P, Gauthier-Clerc M (2009) Relating demographic performance to breeding-site location in the King Penguin. Condor 111:81–87

Dexheimer M, Southern WE (1974) Breeding-success relative to nest location and density in Ring-billed Gull colonies. Wilson Bull 86:288–290

Dubois F, Cézilly F (2002) Breeding success and mate retention in birds: a meta-analysis. Behav Ecol Sociobiol 52:357–364

Dubois F, Cézilly F, Pagel MD (1998) Mate fidelity and coloniality in waterbirds: a comparative analysis. Oecologia 116:433–440

Duffy DC (1983) Competition for nesting space among Peruvian Guano birds. Auk 100:680–688

Elliot RD (1985) The exclusion of avian predators from aggregations of nesting Lapwings (Vanellus vanellus). Anim Behav 33:308–314

Ens BJ, Weissing FJ, Drent RH (1995) The despotic distribution and deferred maturity: two sides of the same coin. Am Nat 146:625–650

Forster IP, Phillips RA (2009) Influence of nest location, density and topography on breeding success in the Black-Browed Albatross Thalassarche melanophris. Mar Ornithol 37:213–217

Frere E, Gandini P, de Boersma P (1992) Effects of nest type on reproductive success of the Magellanic Panguin Spheniscus magellanicus. Mar Ornithol 20:1–6

Fretwell SD (1972) Populations in seasonal environments. Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ

Fretwell SD, Lucas HLJ (1970) On territorial behaviour and other factors influencing habitat distribution in birds. Acta Biotheor 19:16–36

Garamszegi LZ, Eens M, Hurtez-Boussès S, Møller AP (2005) Testosterone, testes size, and mating success in birds: a comparative study. Horm Behav 47:389–409

Gibbs HM, Norman FI, Ward SJ (2000) Reproductive parameters, chick growth and adult ‘age’ in Australasian Gannets Morrus serrator breeding in Port Philip Bay, Victoria, in 1994-95. Emu 100:175–185

Gochfeld M (1980) Timing of breeding and chick mortality in central and peripheral nests of Magellanic Penguins. Auk 97:191–193

Götmark F, Andersson M (1984) Colonial breeding reduces nest predation in the common gull (Larus canus). Anim Behav 32:485–492

Grieco F (1994) Fledging rate in the Cormorant Phalacrocorax carbo at the colony of Val Campotto (Po Delta, N-E Italy). Avocetta 18:57–61

Hagan JM, Walters JR (1990) Foraging behaviour, reproductive success, and colonial nesting in ospreys. Auk 107:506–521

Haymes GT, Blokpoel H (1980) The influence of age on breeding biology of Ring-billed Gulls. Wilson Bull 92:221–228

Hull CL, Hindell M, Le Mar K, Scofield P, Wilson J, Lea M-A (2004) The breeding biology and factors affecting reproductive success in rockhopper penguins Eudyptes chrysocome at Macquarie Island. Polar Biol 27:711–720

Jovani R, Grimm V (2008) Breeding synchrony in colonial birds: from local stress to global harmony. Proc R Soc Lond B 275:1557–1563

Kennedy M, Gray RD, Spencer HG (2000) The phylogenetic relationships of the shags and cormorants: can sequence data resolve a disagreement between behavior and morphology? Mol Phylogenet Evol 17:345–359

Léger C, McNeil R (1987) Nest placement choice in cormorants (Phalacrocorax auritus) from the Madeleine Islands, Québec. Can J Zool 65:24–34

Ludwig JP (1974) Recent changes in the Ring-billed Gull population and biology in the Laurential Great Lakes. Auk 91:575–594

Mínguez E, Belliure I, Ferrer M (2001) Bill size in relation to position in the colony in the Chinstrap Penguin. Waterbirds 24:34–38

Minias P, Kaczmarek K (2013) Is it always beneficial to breed in the centre? Trade-offs in nest site selection within the colony of a tree-nesting waterbird. J Ornithol 154:945–953

Minias P, Kaczmarek K, Janiszewski T, Wojciechowski Z (2011) Spatial variation in clutch size and egg size within the colony of Whiskered Terns (Chlidonias hybrida). Wilson J Ornithol 123:486–491

Minias P, Kaczmarek K, Janiszewski T (2012a) Distribution of pair quality in a tree-nesting waterbird colony: central-periphery model vs. satellite model. Can J Zool 90:861–867

Minias P, Lesner B, Janiszewski T (2012b) Nest location affects chick growth rates in Whiskered Terns Chlidonias hybrida. Bird Study 59:372–375

Minias P, Janiszewski T, Lesner B (2013) Central-periphery gradients of chick survival within the colony of Whiskered Terns Chlidonias hybrida may be explained by the variation in the maternal effects of egg size. Acta Ornithol 48:179–186

Møller AP (1995) Developmental stability and ideal despotic distribution of blackbirds in a patchy environment. Oikos 72:228–334

Møller AP, Sorci G, Erritze J (1998) Sexual dimorphism in immune defense. Am Nat 152:605–619

Montevecchi WA (1978) Nest site selection and its survival value among laughing gulls. Behav Ecol Sociobiol 4:143–161

Mooers AO, Cotgreave P (1994) Sibley and Ahlquist’s tapestry dusted off. Trends Ecol Evol 9:458–459

Murphy EC, Schauer JH (1996) Synchrony in egg-laying and reproductive success of neighboring Common Murres, Uria aalge. Behav Ecol Sociobiol 39:245–258

Nunn CL (1999) The number of males in primate social groups: a comparative test of the socioecological model. Behav Ecol Sociobiol 46:1–13

Olmos S (2003) Nest location, clutch size and nest success in the Scarlet Ibis Eudocimus ruber. Ibis 145:E12–E18

Olson VA, Liker A, Freckleton RP, Székely T (2008) Parental conflict in birds: comparative analyses of offspring development, ecology and mating opportunities. Proc R Soc Lond B 275:301–307

Oro D (2008) Living in a ghetto within a local population: an empirical example of an ideal despotic distribution. Ecology 89:838–846

Ospina-Alvarez A (2008) Coloniality of Brown Booby (Sula leucogaster) in Gorgona National Natural Park, Eastern Tropical Pacific. Ornitol Neotrop 19:517–529

Pagel M (1994) Detecting correlated evolution on phylogenies: a general method for the comparative analysis of discrete characters. Proc R Soc Lond B 255:37–45

Pagel M (1997) Inferring evolutionary processes from phylogenies. Zool Scr 26:331–348

Pagel M (1999) The maximum likelihood approach to reconstructing ancestral character states of discrete characters on phylogenies. Syst Biol 48:612–622

Pagel M, Meade A (2008) BayesTraits. Available at: <http://www.evolution.rdg.ac.uk/BayesTraits.htlm>

Patterson IJ (1965) Timing and spacing of broods in the Black-headed Gull Larus rididbundus. Ibis 107:433–459

Petit LJ, Petit DR (1996) Factors governing habitat selection by prothonotary warblers: field tests of the Fretwell-Lucas models. Ecol Monogr 66:367–387

Post W (1990) Nest survival in a large ibis-heron colony during a three-year decline to extinction. Colon Waterbirds 13:50–61

Pugasek BH, Diem KL (1983) A multivariate study of the relationship of parental age to reproductive success in California Gulls. Ecology 64:829–839

Pyk TM, Bunce A, Norman FI (2008) The influence of age on reproductive success and diet in Australasian gannets (Morus serrator) breeding at Pope’s Eye, Port Phillip Bay, Victoria. Aust J Zool 55:267–274

Ramos JA (2002) Spatial patterns of breeding parameters in tropical Roseate Terns differ from temperate seabirds. Waterbirds 25:285–294

Ranglack GS, Angus RA, Marion KR (1991) Physical and temporal factors influencing breeding success of Cattle Egrets (Bubulcus ibis) in a West Alabama colony. Colon Waterbirds 14:140–149

Regehr HM, Rodway MS, Montevecchi WA (1998) Antipredator benefits of nest-site selection in Black-legged Kittiwakes. Can J Zool 76:910–915

Rendón MA, Garrido A, Ramírez JM, Rendón-Martos M, Amat JA (2001) Despotic establishment of breeding colonies of greater flamingos, Phoenicopterus ruber, in southern Spain. Behav Ecol Sociobiol 50:55–60

Roberts G (1996) Why individual vigilance declines as group size increases. Anim Behav 51:1077–1086

Rolland C, Danchin E, de Fraipont M (1998) The evolution of coloniality in birds in relation to food, habitat, predation, and life-history traits: a comparative analysis. Am Nat 151:514–529

Ryder JP (1975) Egg-laying, egg size, and success in relation to immature-mature plumage of Ring-billed Gulls. Wilson Bull 87:534–542

Ryder PL, Ryder JP (1981) Reproductive performance of Ring-billed Gulls in relation to nest location. Condor 83:57–60

Samraoui F, Menaï R, Samraoui B (2007) Reproductive ecology of the Cattle Egret (Bubulcus ibis) at Sidi Achour, north-eastern Algeria. Ostrich 78:481–487

Serrano D, Tella JL (2007) The role of despotism and heritability in determining settlement patterns in the colonial Lesser Kestrel. Am Nat 169:E53–E67

Shaw P (1985) Age-differences within breeding pairs of Blue-eyed Shags Phalacrocorax atriceps. Ibis 127:537–543

Sheldon FH (1987) Phylogeny of herons estimated from DNA-DNA hybridization data. Auk 104:97–108

Sheldon FH, Gill FB (1996) A reconsideration of songbird phylogeny, with emphasis on the evolution of titmice and their sylvioid relatives. Syst Biol 45:473–495

Si Bachir S, Barbraud C, Doumandji S, Hafner H (2008) Nest site selection and breeding success in an expanding species, the Cattle Egret Bubulcus ibis. Ardea 96:99–107

Sibley CG, Ahlquist JE (1990) Phylogeny and Classification of Birds. Yale University Press, New Haven

Siegel-Causey D, Hunt GL Jr (1981) Colonial defense behavior in Double-crested and Pelagic Cormorants. Auk 98:522–531

Siegel-Causey D, Hunt GL Jr (1986) Breeding site selection and colony formation in Double-crested and Pelagic Cormorants. Auk 103:230–234

Siegel-Causey D, Kharitonov SP (1990) The evolution of coloniality. In: Power DM (ed) Current Ornithology, vol 7. Plenum Press, New York, pp 285–330

Siegfried WF (1972) Breeding success and reproductive output of the Cattle Egret. Ostrich 43:43–55

Smith ND (2010) Phylogenetic analysis of Pelecaniformes (Aves) based on osteological data: implications for waterbird phylogeny and fossil calibration studies. PLoS ONE 5:e13354

Spurr EB (1975) Breeding of the Adélie Penguin Pygoscelis adeliae at Cape Bird. Ibis 117:324–338

Staverees L, Crawford RJM, Underhill LG (2008) Factors influencing breeding success of Cape Gannet Morus capensis at Malgas Island in 2002/2003. Ostrich 79:62–72

Svagelj WS, Quintana F (2011) Breeding performance of the Imperial Shag (Phalacrocorax atriceps) in relation to year, laying date and nest location. Emu 111:162–165

Taylor RH (1962) The Adelie Penguin Pygoscelis adeliae at Cape Royds. Ibis 104:176–204

Tella JL (2002) The evolutionary transition to coloniality promotes higher blood parasitism in birds. J Evol Biol 15:32–41

Tenaza R (1971) Behavior and nesting success relative to nest location in Adelie Penguin (Pygoscelis adeliae). Condor 73:81–92

Thomas GH, Wills MA, Székely T (2004) A supertree approach to shorebird phylogeny. BMC Evol Biol 4:28

Uzun A (2009) Do the height and location of Black-Crowned Night Heron (Nycticorax nycticorax) nests affect egg production and breeding success? Waterbirds 32:357–359

Uzun A, Kopij G (2010) Effect of the colony edge on the clutch size and fledging success in the Little Egrets Egretta garzetta (L.). Pol J Ecol 58:393–396

Van Vessem J, Draulans D (1986) The adaptive significance of colonial breeding in the Grey Heron Ardea cinerea: inter- and intra-colony variability in breeding success. Ornis Scand 17:356–362

Varela SAM, Danchin É, Wagner RH (2007) Does predation select for or against avian coloniality? A comparative analysis. J Evol Biol 20:1490–1503

Velando A, Freire J (2001) How general is the central-periphery distribution among seabird colonies? Nest spatial pattern in the European Shag. Condor 103:544–554

Velando A, Freire J (2003) Nest-site characteristics, occupation and breeding success in the European Shag. Waterbirds 26:473–483

Vergara P, Aguirre JI (2006) Age and breeding success in relation to nest position in a White Stork Ciconia ciconia colony. Acta Oecol 30:414–418

Wooller RD, Coulson JC (1977) Factors affecting the age of first breeding in the Kittiwake Rissa tridactyla. Ibis 119:339–349

Yorio P, Quintana F (1997) Predation by Kelp Gulls Larus dominicanus at a mixed species colony of Royal Terns Sterna maxima and Cayenne Terns Sterna eurygnatha in Patagonia. Ibis 139:536–541

Acknowledgments

I appreciate the comments and discussion by Jerzy Bańbura and Krzysztof Kaczmarek. I also wish to thank the Associate Editor, Charles R. Brown, and an anonymous reviewer for their constructive suggestions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Communicated by C. R. Brown

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License which permits any use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and the source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Minias, P. Evolution of within-colony distribution patterns of birds in response to habitat structure. Behav Ecol Sociobiol 68, 851–859 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00265-014-1697-8

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00265-014-1697-8