Abstract

Summary

In this study of 100,949 new users of oral bisphosphonates age ≥35 years, “early quitters” were found to differ from others with poor refill compliance in terms of socioeconomic, demographic, and treatment-related characteristics. New risk factors for poor compliance and persistence were identified.

Introduction

Poor compliance with anti-osteoporotic therapy is an on-going worldwide challenge. In this study, we hypothesized that “early quitters” differ in socioeconomics, demographics, co-medications, and comorbid conditions from other patients with low compliance.

Methods

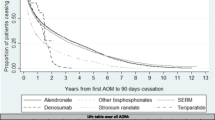

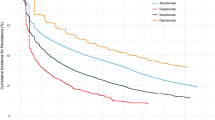

The study was a register-based nationwide cohort study of anti-osteoporotic therapy comprising 100,949 men and women. Statistical analysis including backward stepwise logistic regression analysis was used to explain causes of treatment failure and Kaplan–Meier survival analysis to estimate persistence of treatment.

Results

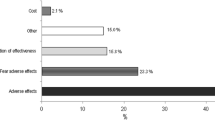

It was noted that 56.6 % of the patients were persistent and compliant, 4.7 % of the patients were persistent but “low compliant” while 38.7 % of the patients were “early quitters”. “Early quitters” were found to differ in socioeconomics from “low compliant” patients. Differences concerning increased risk of “early quitters” were associated with high household income, subjects’ age 71.9–79 years, living in the countryside or village, prior treatment with analgesics and anti-parkinson drugs, and dementia. Differences concerning decreased risk of “early quitters” were associated with male, living in an apartment, children living at home, living close to a university hospital, anti-osteoporotic therapy other than alendronate, number of drugs especially above three, pulmonary disease, collagen disease.

Conclusion

The results suggest a need for improved support for patients to facilitate the interpretation of the disease and the perception of the benefits and risks of treatment—to reduce the risk of “early quitters”. We were able to identify new risk groups that may be candidates for targeted actions.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Cadarette SM, Burden AM (2010) Measuring and improving adherence to osteoporosis pharmacotherapy. Curr Opin Rheumatol 22(4):397–403. doi:10.1097/BOR.0b013e32833ac7fe

Genant HK, Cooper C, Poor G, Reid I, Ehrlich G, Kanis J et al (1999) Interim report and recommendations of the World Health Organization Task-Force for Osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int 10(4):259–264. doi:10.1007/s001980050224

Sundhedsstyrelsen. Sund hele livet—de nationale mål og strategier for folkesundheden 2002–10. http://www.folkesundhed.dk/media/sundhelelivet.pdf. 2008

WHO. The World Health Report. http://www.who.int/whr/2008/en/index.html. 2008

Reginster JY, Burlet N (2006) Osteoporosis: a still increasing prevalence. Bone 38(2 Suppl 1):S4–S9. doi:10.1016/j.bone.2005.11.024

Christensen PM, Brixen K, Gyrd-Hansen D, Kristiansen IS (2005) Cost-effectiveness of alendronate in the prevention of osteoporotic fractures in Danish women. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol 96(5):387–396. doi:10.1111/j.1742-7843.2005.pto_08.x

Abrahamsen B, van Staa T, Ariely R, Olson M, Cooper C (2009) Excess mortality following hip fracture: a systematic epidemiological review. Osteoporos Int 20(10):1633–1650. doi:10.1007/s00198-009-0920-3

Cooper C, Harvey NC (2012) Osteoporosis risk assessment. BMJ 344:e4191. doi:10.1136/bmj.e4191

Landfeldt E, Strom O, Robbins S, Borgstrom F (2012) Adherence to treatment of primary osteoporosis and its association to fractures—the Swedish Adherence Register Analysis (SARA). Osteoporos Int 23(2):433–443. doi:10.1007/s00198-011-1549-6

Roerholt C, Eiken P, Abrahamsen B (2009) Initiation of anti-osteoporotic therapy in patients with recent fractures: a nationwide analysis of prescription rates and persistence. Osteoporos Int 20(2):299–307. doi:10.1007/s00198-008-0651-x

Siris ES, Harris ST, Rosen CJ, Barr CE, Arvesen JN, Abbott TA et al (2006) Adherence to bisphosphonate therapy and fracture rates in osteoporotic women: relationship to vertebral and nonvertebral fractures from 2 US claims databases. Mayo Clin Proc 81(8):1013–1022, AN 21973041

Imaz I, Zegarra P, Gonzalez-Enriquez J, Rubio B, Alcazar R, Amate JM (2010) Poor bisphosphonate adherence for treatment of osteoporosis increases fracture risk: systematic review and meta-analysis. Osteoporos Int 21(11):1943–1951. doi:10.1007/s00198-009-1134-4

Kothawala P, Badamgarav E, Ryu S, Miller RM, Halbert RJ (2007) Systematic review and meta-analysis of real-world adherence to drug therapy for osteoporosis. Mayo Clin Proc 82(12):1493–1501, AN 27828553

Silverman S, Gold DT (2010) Compliance and persistence with osteoporosis medications: a critical review of the literature. Rev Endocr Metab Disord 11(4):275–280. doi:10.1007/s11154-010-9138-0

Lindberg MJ, Andersen SE, Christensen HR, Kampmann JP (2008) Compliance to drug prescriptions. Ugeskr Laeger 170(22):1912–1916

WHO. Adherence to long-term therapies evidence for action. http://www.who.int/chp/knowledge/publications/adherence_full_report.pdf. 2008.

Balkrishnan R (1998) Predictors of medication adherence in the elderly. Clin Ther 20(4):764–771. doi:10.1016/S0149-2918(98)80139-2

Barat I, Andreasen F, Damsgaard EM (2001) Drug therapy in the elderly: what doctors believe and patients actually do. Br J Clin Pharmacol 51(6):615–622. doi:10.1046/j.0306-5251.2001.01401.x

Ciechanowski PS, Katon WJ, Russo JE, Walker EA (2001) The patient–provider relationship: attachment theory and adherence to treatment in diabetes. Am J Psychiatry 158(1):29–35. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.158.1.29

DiMatteo MR (2004) Social support and patient adherence to medical treatment: a meta-analysis. Health Psychol 23(2):207–218, AN: 00003615-200403000-00014

Griffith S (1990) A review of the factors associated with patient compliance and the taking of prescribed medicines. Br J Gen Pract 40(332):114–116, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1371078/pdf/brjgenprac00082-0026.pdf

Lassen LC (1989) Patient compliance in general practice. Scand J Prim Health Care 7(3):179–180, http://informahealthcare.com/doi/pdf/10.3109/02813438909087237

Block AE, Solomon DH, Cadarette SM, Mogun H, Choudhry NK (2008) Patient and physician predictors of post-fracture osteoporosis management. J Gen Intern Med 23(9):1447–1451. doi:10.1007/s11606-008-0697-7

Cortet B, Benichou O (2006) Adherence, persistence, concordance: do we provide optimal management to our patients with osteoporosis? Joint Bone Spine 73(5):e1–e7. doi:10.1016/j.jbspin.2006.02.006

McLeod KM, Johnson CS (2011) A systematic review of osteoporosis health beliefs in adult men and women. J Osteoporos 2011:1–11. doi:10.4061/2011/197454

Danmarks Statistik. Statistikbanken. http://www.statistikbanken.dk/statbank5a/default.asp?w=1280 2008

Barker C (2009) The mean, median, and confidence intervals of Kaplan–Meier survival estimate—computations and applications. Am Stat 63(1):78–80. doi:10.1198/tast.2009.0015

Nielsen DS, Langdahl BL, Sorensen OH, Sorensen HA, Brixen KT (2010) Persistence to medical treatment of osteoporosis in women at three different clinical settings—a historical cohort study. Scand J Publ Health 38(5):502–507. doi:10.1177/1403494810371243

Devold HM, Furu K, Skurtveit S, Tverdal A, Falch JA, Sogaard AJ (2012) Influence of socioeconomic factors on the adherence of alendronate treatment in incident users in Norway. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 21(3):297–304. doi:10.1002/pds.2344

Wastesson JW, Ringback WG, Parker MG, Johnell K (2012) Educational level and use of osteoporosis drugs in elderly men and women: a Swedish nationwide register-based study. Osteoporos Int. doi:10.1007/s00198-012-1945-6

Sale JE, Beaton DE, Sujic R, Bogoch ER (2010) ‘If it was osteoporosis, I would have really hurt myself’. Ambiguity about osteoporosis and osteoporosis care despite a screening programme to educate fragility fracture patients. J Eval Clin Pract 16(3):590–596. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2753.2009.01176.x

Meadows ES, Mitchell BD, Bolge SC, Johnston JA, Col NF (2012) Factors associated with treatment of women with osteoporosis or osteopenia from a national survey. BMC Womens Health 12:1. doi:10.1186/1472-6874-12-1

Fraenkel L, Gulanski B, Wittink D (2006) Patient treatment preferences for osteoporosis. Arthritis Rheum 55(5):729–735. doi:10.1002/art.22229

Haynes RB, Yao X, Degani A, Kripalani S, Garg A, McDonald HP (2005) Interventions to enhance medication adherence. Cochrane Database Syst Rev (4):CD000011. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD000011.pub3

Conflicts of interest

B. Abrahamsen has served as an investigator in clinical trials and on advisory boards and/or speakers panels for pharmaceutical companies that produce osteoporosis drugs. Clinical trials: Amgen, NPS Pharmaceuticals. Advisory boards: Amgen, Takeda-Nycomed. Speakers panels: Amgen, Nycomed, Eli Lilly, Merck.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Allocated funds from University of Southern Denmark, Gentofte University Hospital, Capital Region, Research Foundation for Health Research, Aase and Ejnar Danielsens Foundation, The Osteoporosis Society Denmark, Cabinetmaker Sophus Jacobsen and wife Astrid Jacobsens Fond

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hansen, C., Pedersen, B.D., Konradsen, H. et al. Anti-osteoporotic therapy in Denmark—predictors and demographics of poor refill compliance and poor persistence. Osteoporos Int 24, 2079–2097 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-012-2221-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-012-2221-5