Abstract

Introduction and hypothesis

In recent years the number of caesarean sections has increased worldwide for different reasons. to review the scientific evidence relating to the impact of the type of delivery on pelvic floor disorders (PFDs) such as urinary and faecal incontinence and pelvic organ prolapse.

Methods

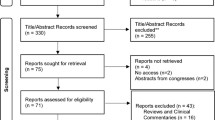

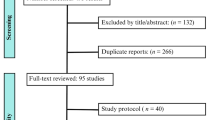

A review of systematic reviews and meta-analysis, drawn from the following databases: MEDLINE (via PubMed), Scopus, Web of Science, The Cochrane Library and LILACS (Literatura Latinoamericana y del Caribe en Ciencias de la Salud/Latin American and Caribbean Health Sciences Literature) prior to January 2019. The directives of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses were used in assessing article quality.

Results

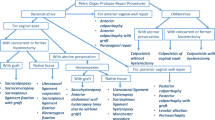

Eleven systematic reviews were evaluated, 6 of which found a significantly decreased risk of urinary incontinence associated with caesarean section and 3 meta-analyses showed a significant reduction in POP for caesarean section, compared with vaginal delivery. Of 5 reviews that examined delivery type and faecal incontinence, only one indicated a lower incidence of faecal incontinence associated with caesarean delivery. However, most of the studies included in these reviews were not adjusted for important confounding factors and the risk of PFDs was not analysed by category of caesarean delivery (elective or urgent).

Conclusion

When compared with vaginal delivery, caesarean is associated with a reduced risk of urinary incontinence and pelvic organ prolapse. These results should be interpreted with caution and do not help to address the question of whether elective caesareans are protective of the maternal pelvic floor.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Hallock JL, Handa VL. The epidemiology of pelvic floor disorders and childbirth: an update. Obstet Gynecol Clin N Am. 2016;43:1–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ogc.2015.10.008.

Islam RM, Oldroyd J, Rana J, Romero L, Karim MN. Prevalence of symptomatic pelvic floor disorders in community-dwelling women in low and middle-income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int Urogynecol J. 2019;30:2001–11. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-019-03992-z.

Rortveit G, Subak LL, Thom DH, et al. Urinary incontinence, fecal incontinence and pelvic organ prolapse in a population-based, racially diverse cohort: prevalence and risk factors. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2010;16:278–83. https://doi.org/10.1097/SPV.0b013e3181ed3e31.

Mirskaya M, Lindgren EC, Carlsson IM. Online reported women’s experiences of symptomatic pelvic organ prolapse after vaginal birth. BMC Womens Health. 2019;19:129. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-019-0830-2.

Milsom I, Coyne KS, Nicholson S, Kvasz M, Chen CI, Wein AJ. Global prevalence and economic burden of urgency urinary incontinence: a systematic review. Eur Urol. 2014;65:79–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eururo.2013.08.031.

Sung VW, Washington B, Raker CA. Costs of ambulatory care related to female pelvic floor disorders in the United States. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;202:483.e1–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2010.01.015.

Wu JM, Kawasaki A, Hundley AF, Dieter AA, Myers ER, Sung VW. Predicting the number of women who will undergo incontinence and prolapse surgery, 2010 to 2050. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;205:230.e1–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2011.03.046.

Handa VL, Blomquist JL, McDermott KC, Friedman S, Munoz A. Pelvic floor disorders after vaginal birth: effect of episiotomy, perineal laceration, and operative birth. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;119(2 Pt 1):233–9. https://doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0b013e318240df4f.

Chow D, Rodriguez LV. Epidemiology and prevalence of pelvic organ prolapse. Curr Opin Urol. 2013;23(4):293–8. https://doi.org/10.1097/MOU.0b013e3283619ed0.

Yuaso DR, Santos JLF, Castro RA, et al. Female double incontinence: prevalence, incidence, and risk factors from the SABE (health, wellbeing and aging) study. Int Urogynecol J. 2018;29:265–72. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-017-3365-9.

Sandall J, Tribe RM, Avery L, et al. Short-term and long-term effects of caesarean section on the health of women and children. Lancet. 2018;392:1349–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31930-5.

Betran AP, Torloni MR, Zhang JJ, Gülmezoglu AM, WHO Working Group on Caesarean Section. WHO statement on caesarean section rates. BJOG. 2016;123:667–70. https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-0528.13526.

Betran AP, Ye J, Moller AB, Zhang J, Gulmezoglu AM, Torloni MR. The increasing trend in caesarean section rates: global, regional and national estimates: 1990–2014. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0148343. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0148343.

Mariani GL, Vain NE. The rising incidence and impact of non-medically indicated pre-labour cesarean section in Latin America. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med. 2019;24:11–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.siny.2018.09.002.

Stoll KH, Hauck YL, Downe S, Payne D, Hall WA; International childbirth attitudes—prior to pregnancy (ICAPP) study team. Preference for cesarean section in young nulligravid women in eight OECD countries and implications for reproductive health education. Reprod Health. 2017;14:116. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-017-0354-x.

Wanden-Berghe C, Sanz-Valero J. Systematic reviews in nutrition: standardized methodology. Br J Nutr. 2012;107(Suppl 2):S3–7. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007114512001432.

Gea Cabrera A, Sanz-Lorente M, Sanz-Valero J, López-Pintor E. Compliance and adherence to enteral nutrition treatment in adults: a systematic review. Nutrients. 2019;11:2627. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu11112627.

Sanz-Valero J, Casterá VT, Wanden-Berghe C. Bibliometric study of scientific output published by the Revista Panamericana de Salud Pública/pan American journal of public health from 1997–2012. Rev Panam Salud Publica. 2014;35:81–8.

Hutton B, Catala-Lopez F, Moher D. The PRISMA statement extension for systematic reviews incorporating network meta-analysis: PRISMA-NMA. Med Clin (Barc). 2016;147:262–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.medcli.2016.02.025.

Azam S, Khanam A, Tirlapur S, Khan K. Planned caesarean section or trial of vaginal delivery? A meta-analysis. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2014;26:461–8. https://doi.org/10.1097/GCO.0000000000000114.

Keag OE, Norman JE, Stock SJ. Long-term risks and benefits associated with cesarean delivery for mother, baby, and subsequent pregnancies: systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 2018;15:e1002494. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1002494.

Leng B, Zhou Y, Du S, et al. Association between delivery mode and pelvic organ prolapse: a meta-analysis of observational studies. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2019;235:19–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejogrb.2019.01.031.

Nelson RL, Furner SE, Westercamp M, Farquhar C. Cesarean delivery for the prevention of anal incontinence. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;2010:CD006756. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD006756.pub2.

Nelson RL, Go C, Darwish R, et al. Cesarean delivery to prevent anal incontinence: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Tech Coloproctol. 2019;23:809–20. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10151-019-02029-3.

Nelson RL, Westercamp M, Furner SE. A systematic review of the efficacy of cesarean section in the preservation of anal continence. Dis Colon Rectum. 2006;49:1587–95. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10350-006-0660-9.

Press JZ, Klein MC, Kaczorowski J, Liston RM, von Dadelszen P. Does cesarean section reduce postpartum urinary incontinence? A systematic review. Birth. 2007;34:228–37. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1523-536X.2007.00175.x.

Pretlove SJ, Thompson PJ, Toozs-Hobson PM, Radley S, Khan KS. Does the mode of delivery predispose women to anal incontinence in the first year postpartum? A comparative systematic review. BJOG. 2008;115(4):421–34. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-0528.2007.01553.x.

Tähtinen RM, Cartwright R, Tsui JF, et al. Long-term impact of mode of delivery on stress urinary incontinence and urgency urinary incontinence: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Urol. 2016;70:148–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eururo.2016.01.037.

Thom DH, Rortveit G. Prevalence of postpartum urinary incontinence: a systematic review. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2010;89:1511–22. https://doi.org/10.3109/00016349.2010.526188.

Yang XJ, Sun Y. Comparison of caesarean section and vaginal delivery for pelvic floor function of parturients: a meta-analysis. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2019;235:42–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejogrb.2019.02.003.

Hannah ME, Hannah WJ, Hodnett ED, et al. Term breech trial 3-month follow-up collaborative group. Outcomes at 3 months after planned cesarean vs planned vaginal delivery for breech presentation at term: the international randomized term breech trial. JAMA. 2002;287:1822–31. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.287.14.1822.

Hannah ME, Whyte H, Hannah WJ, et al. Term breech trial 3-month follow-up collaborative group. Maternal outcomes at 2 years after planned cesarean section versus planned vaginal birth for breech presentation at term: the international randomized term breech trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;191:917–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2004.08.004.

Hutton EK, Hannah ME, Willan AR, et al. Twin birth study collaborative group. Urinary stress incontinence and other maternal outcomes 2 years after caesarean or vaginal birth for twin pregnancy: a multicentre randomised trial. BJOG. 2018;125:1682–90. https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-0528.15407.

Wilson D, Dornan J, Milsom I, Freeman R. UR-CHOICE: can we provide mothers-to-be with information about the risk of future pelvic floor dysfunction? Int Urogynecol J. 2014;25(11):1449–52. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-014-2376-z.

Bernabeu-Martínez MA, Ramos Merino M, Santos Gago JM, Álvarez Sabucedo LM, Wanden-Berghe C, Sanz-Valero J. Guidelines for safe handling of hazardous drugs: a systematic review. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0197172. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0197172.

Acknowledgements

José Alvaro Beviá Romero helped with the data collection and first description of the results.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

None.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

ESM 1

(DOC 64 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

López-López, A.I., Sanz-Valero, J., Gómez-Pérez, L. et al. Pelvic floor: vaginal or caesarean delivery? A review of systematic reviews. Int Urogynecol J 32, 1663–1673 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-020-04550-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-020-04550-8