Abstract

Purpose

We evaluated the impact of increasing tidal volume (V t), decreased chest wall compliance, and left ventricular (LV) contractility during intermittent positive-pressure ventilation (IPPV) on the relation between pulse pressure (PP) and LV stroke volume (SVLV) variation (PPV and SVV, respectively), and intrathoracic blood volume (ITBV) changes.

Methods

Sixteen pentobarbital-anesthetized thoracotomized mongrel dogs were studied both before and after propranolol-induced acute ventricular failure (AVF) (n = 4), with and without chest and abdominal pneumatic binders to decrease chest wall compliance (n = 6), and during V t of 5, 10, 15, and 25 ml/kg (n = 6). SVLV and right ventricular stroke volume (SVRV) were derived from electromagnetic flow probes around aortic and pulmonary artery roots. Arterial pressure was measured in the aorta using a fluid-filled catheter. Arterial PPV and SVV were calculated over three breaths as (max − min)/[(max + min)/2]. ITBV changes during ventilation were inferred from the beat-to-beat volume differences between SVRV and SVLV.

Results

Arterial PP and SVLV were tightly correlated during IPPV under all conditions (r 2 = 0.85). Both PPV and SVV increased progressively as V t increased and with thoraco-abdominal binding, and tended to decrease during AVF. SVRV phasically decreased during inspiration, whereas SVLV phasically decreased 2–3 beats later, such that ITBV decreased during inspiration and returned to apneic values during expiration. ITBV decrements increased with increasing V t or with thoraco-abdominal binding, and decreased during AVF owing to variations in SVRV, such that both PPV and SVV tightly correlated with inspiration-associated changes in SVRV and ITBV.

Conclusion

Arterial PP and SVLV are tightly correlated during IPPV and their relation is not altered by selective changes in LV contractility, intrathoracic pressure, or V t. However, contractility, intrathoracic pressure, and V t directly alter the magnitude of PPV and SVV primarily by altering the inspiration-associated decreases in SVRV and ITBV.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Intermittent positive-pressure ventilation (IPPV) alters venous return (VR) and left ventricular (LV) ejection pressure by altering intrathoracic pressure (ITP), right ventricular (RV) stroke volume (SVRV), and intrathoracic blood volume (ITBV) [1]. These interactions cause ventilator-dependent arterial pulse pressure (PP) and LV stroke volume (SVLV) variations (PPV and SVV, respectively). The magnitude of PPV and SVV during IPPV predict preload responsiveness in humans [2–5]. Not surprisingly, De Backer et al. [6] showed that changing tidal volume (V t), the primary forcing function altering VR, independently alters PPV. We previously explored this interaction in our canine model and humans, showing that neither systolic pressure variation nor PPV correlated with changes in SVLV or measures of cardiac preload such as LV end-diastolic volume [7, 8]. Although these and other data form the basis for the argument that absolute measures of preload do not predict volume responsiveness [2], other technical issues may cause some of these seemingly contradictory findings. For example, we previously showed in an animal model that sampling duration, V t, and contractility influence calculated PPV and SVV [9]. However, that study and others by our group cited above used conductance catheter-derived measures of SVLV, which can be prone to parallel conductance artifact and incomplete LV volume sampling [10]. Furthermore, it seems likely that arterial PP should reflect SVLV on a beat-to-beat basis since ventriculo-arterial coupling defines that arterial PP is a function of SVLV and central arterial compliance.

Since there is increasing interest in the use of both PPV and SVV to predict preload responsiveness and drive resuscitation protocols [11] we strove to document the relationship between PP and SVLV changes as baseline conditions varied over clinically relevant ranges, and define the degree to which alterations in VR and ITBV during IPPV cause these effects. Thus, we compared the relationship between PP and SVLV and the impact of various pulmonary and cardiovascular factors known to alter both PP and SVLV, including changes in V t, chest wall compliance, and cardiac contractility. Secondarily, we examined the impact of ventilation on VR, as estimated by SVRV changes, and the subsequent phasic changes in ITBV, as quantified by the volume difference between paired SVRV and SVLV over a single breath. We measured SVRV and SVLV directly using calibrated flow probes placed around the main pulmonary artery and aortic root, respectively, in an intact canine model. We hypothesized that PP and SVLV would be tightly coupled under all conditions and that the causes of IPPV-associated PPV and SVV would be the ventilation-induced changes in VR causing a phasic decrease in LV filling as quantified by proportional inspiratory decreases in ITBV.

Methods

After approval by our Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee, 16 mongrel dogs were anesthetized with intravenous pentobarbital sodium (30 ml/kg) and intubated with a 9.0-mm-ID cuffed endotracheal tube equipped with a distal port to measure airway pressure (P aw). Ventilation during the surgical procedure was accomplished by a constant-volume (10 ml/kg) ventilator (Harvard Apparatus, Cambridge, MA) with enriched inspired O2. The details of the surgical procedure and data collection have been previously described by us [1, 12] and are also listed in the electronic repository of the journal (ESM).

Protocol

The protocol consisted of noting the effects of IPPV on paired arterial PP and SVLV values across conditions as well as the dynamic changes in paired SVRV and SVLV causing changes in ITBV, with a greater SVLV connoting a decreasing ITBV and vice versa.

We studied the effects of IPPV under control conditions and after the induction of acute ventricular failure (AVF) with different V t and with normal or reduced chest wall compliance. Control was taken to be the hemodynamically stable postoperative state described above. IPPV was performed at 10 ml/kg, as described above during the surgical procedure, and then at varying V t from 5, 10, 15, and 25 ml/kg. In an attempt to independently increase ITP without concomitant increases in pulmonary vascular resistance, lung volume, or significantly compromising VR, the following method was used. Inflatable pneumatic binders (8-in. widths) placed around the chest and upper abdomen were inflated to a pressure of 25 mmHg measured at end-expiration. This amount of binder inflation did not increase apneic pleural pressure (P pl) but was associated with an elevated peak inspiratory P pl and an increased left atrial pressure (P la). All animals tolerated the binder inflation well without deterioration in gas exchange. Finally, AVF was induced by a bolus propranolol infusion (1.5–2 mg/kg) as previously described [1, 12]. After the induction of AVF, dextran or autologous blood was infused to return cardiac output to 70% of control. In practice, 10 ml/kg infused volume was required, which resulted in a transmural P la of 12 ± 2 mmHg (mean ± SD). Once baseline AVF values were obtained, the process of varying V t from 5 to 25 ml/kg and altering chest wall compliance was repeated. All animals tolerated the experimental protocol without further hemodynamic deterioration. Gas exchange was adequate without respiratory alkalosis or metabolic acidosis. Arterial PO2 was 236 ± 40 mmHg throughout the experiment.

Data analysis

P aw, aortic pressure, SVLV, and SVRV were simultaneously recorded (Gould, Cleveland, OH). Arterial PP was measured from aorta pressure as the diastolic to systolic pressure difference. Arterial PPV was calculated as 100 × (maximum PP − minimum PP)/[(PPmax + PPmin)/2], where maximum and minimum PP are the extreme PP values over a three-breath period as previously described [4, 13, 14]. LV SVV was calculated as 100 × (maximum SVLV − minimum SVLV)/[(maximum SVLV + minimum SVLV)/2], where maximum and minimum SVLV are the extreme SVLV values at any point in time during the three-breath period. To assess the influence of the above perturbations on PPV and SVV we also measured the instantaneous decrease in SVRV from apneic steady state and the SVLV − SVRV (dynamic ITBV changes) over one breath. Continuous variables are reported as mean ± SD.

Results

Sixteen dogs (18.5–25.7 kg body weight, mean 21.3 ± 2.4 kg) were studied, although no animals had all studies done because we only used data from conditions in which there was hemodynamic stability and in more than half the animals one or more of the steps were associated with intermittent arrhythmias that precluded the measure of PPV or SVV. The effect of IPPV on PP, SV, and both PPV and SVV is reported in Table 1. Baseline PP and SVLV values showed a tight correlation during control IPPV conditions (r 2 = 0.85) (ESM, Fig. 1). During control IPPV conditions, the highest PP and highest SVLV occurred at end-inspiration, and the same phenomenon was observed for the minimal values at initial expiration (Fig. 1). This tight PP–SV coupling was also maintained when increased chest wall compliance or AVF was induced (r 2 = 0.92 and 0.83, respectively) (ESM, Fig. 2).

Effect of different tidal volumes

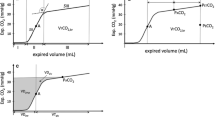

Six dogs were studied with V t of 5, 10, 15, and 25 ml/kg. In two the 25 ml/kg step was not performed for technical reasons. PP and SVLV maintained their coupling when V t was progressively increased from 5, 10, 15, and 25 ml/kg (ESM, Fig. 3) and both PPV and SVV increased in a parallel manner to the increase in V t (Table 1; Fig. 2).

Effect of varying thoraco-abdominal binding

The effect of decreasing chest wall compliance was studied in six dogs resulting in inspiration-associated increases in ITP. Binding also increased both PPV and SVV (24 ± 6 to 39 ± 6, and 24 ± 10 to 40 ± 4%, respectively). However, unlike baseline unbound conditions, wherein systolic arterial pressure varied little during ventilation, during binding systolic arterial pressure increased greatly during inspiration, and independently of changes in arterial PP (Fig. 3).

A strip chart recording of one animal during positive-pressure ventilation (10 ml/kg) under control, control-binder, and acute ventricular failure conditions. See text for discussion. SV RV right ventricular stroke volume, SV LV left ventricular stroke volume, P a arterial pressure, \( P_{{la_{tm} }} \) left atrial transmural pressure, \( P_{{pa_{tm} }} \) pulmonary artery transmural pressure, \( P_{{ra_{tm} }} \) right atrial transmural pressure, P aw airway pressure, P pl pleural pressure. Transmural pressure is vascular pressure relative to P pl. Note that pressure scaling for \( P_{{{\text{ra}}_{\text{tm}} }} \), P aw, and P pl vary across conditions

Effect of altering contractility

AVF was induced in four dogs. Both PPV and SVV decreased with impaired contractility (37 ± 24 to 26 ± 13, and 32 ± 16 to 27 ± 11%, respectively). However, PPV and SVV also increased as V t increased (respective values of PPV and SVV: 8.8 ± 4 and 9.8 ± 3% for 10 ml/kg, 10.0 ± 3 and 11.3 ± 5% for 15 ml/kg, and 10.8 ± 4 and 11.3 ± 3% for 25 ml/kg). Like control-binder conditions, during AVF the primary determinant of the PP increase as V t increased was an inspiration-associated increase in both systolic arterial pressure and PP (Fig. 3).

Effect of different ventilatory maneuvers on dynamic changes in SVRV from apneic steady state and ITBV (Tables 1, 2)

Positive-pressure inspiration caused SVRV to decrease relative to both its apneic baseline value and SVLV, such that ITBV decreased during inspiration, whereas during expiration the opposite was true. These IPPV-inspiration-associated decreases in ITBV were more pronounced as V t increased (Fig. 4). The same increases in ITBV swings were observed during increased chest wall compliance conditions when compared to unbound baseline conditions at constant V t (e.g., at 10 ml/kg V t baseline delta ITBV 15.9 ± 5.9 ml vs. thoraco-abdominal binding 22.2 ± 9.0 ml). As for PPV and SVV, ITBV changes were less pronounced when AVF was induced (9.7 ± 5.6 ml for AVF to 16.3 ± 6.2 ml for baseline). Importantly, all the maximal decreases in ITBV were due selectively to the decreases in SVRV, suggesting that the primary cause of PPV and SVV during IPPV is the phasic decrease in VR.

Discussion

This study has four primary findings. First, PP and SVLV are tightly coupled during IPPV, even with extreme tidal volumes, altered chest wall compliance to markedly increase ITP (at constant tidal volume), and when intrinsic cardiac contractility was impaired. Thus, central arterial compliance is not altered by either the respiratory cycle or changes in V t, chest wall compliance, or contractility. Thus, if PP and SV are measured accurately changes in the PPV/SVV ratio will reflect an actual change in central arterial tone. Second, that PPV and SVV increase proportionally for the same cardiovascular state as V t increases or, for a constant V t, as chest wall compliance decreases. Thus, changes in either V t, as could occur with pressure-limited ventilation, or chest wall compliance, as could occur with increased intra-abdominal pressure, will alter the magnitude of PPV and SVV independent of actual changes in volume responsiveness. Third, the magnitude of PPV and SVV decreased as contractility was pharmacologically impaired, supporting the hypothesis that both PPV and SVV reflect ventricular responsiveness to changes in preload. Fourth, the dynamic changes in ITBV are explained by inspiration-induced decreases in SVRV, and these changes parallel PPV and SVV changes, consistent with the hypothesis that ventilation-induced changes in PPV and SVV reflect ventilation-induced changes in global ventricular preload as quantified by ITBV.

The present data disagree with our previous findings of a dissociated PP and SV during IPPV reported when SVLV was estimated using conductance catheter methodology [7]. In the present study the two variables are tightly coupled. In those previous studies, SVLV was estimated from LV conductance catheter data, and the present study measured SVLV using flow probes around the aortic root. Thus, data derived from conductance catheter technologies should not be used as definitive data when used to measure absolute LV volumes or their changes during IPPV unless externally validated. However, the other findings from those previous studies, namely that varying V t causes PP and SV to also vary independent of volume status remain valid [7, 8]. Since both SVV and PPV are widely used to drive resuscitation protocols in a variety of cardiovascular states [5, 14, 15], documenting that the PPV and SVV changes remain tightly linked despite changes in tidal volume, chest wall compliance, and contractility speak of the robustness of this functional hemodynamic parameter as a marker of preload responsiveness. This V t dependency of PPV was recently underscored by Muller et al. [16] who showed that transpulmonary pressure, and not airway pressure, was a better predictor of PPV in volume responsive patients. Importantly, the ratio of PPV to SVV also defines a dynamic arterial elastance (or vasomotor tone), and can be used to predict the degree to which arterial pressure will increase in a hypotensive but volume responsive subject in response to volume loading [17]. That within a normal physiological range PP and SV are tightly coupled allows for small changes in their relation to identify changes in central arterial tone.

The influence of V t on PPV has been reported by several groups [6, 9, 15]. De Backer et al. [6] showed that PPV was an excellent dynamic index of preload responsiveness when patients were ventilated with tidal volumes higher than or equal to 8 ml/kg. However, the ability of PPV to identify preload responsiveness was not maintained when patients were ventilated with lower V t. Our data on ITBV changes support the cumulative effect of increasing V t on the degree of PPV and SVV, reinforcing the idea that the threshold PPV or SVV value used to predict fluid responsiveness should be altered according to the V t used. The smaller the tidal volume the lower the threshold value needs to be to define fluid responsiveness. Our data demonstrate the primary cause of the observed tidal volume-dependent IPPV-induced PPV and SVV, namely the dynamic swings in VR altering ITBV (Fig. 4).

The thoraco-abdominal binding studies also point to another primary concept in the use of PPV and SVV in the assessment of preload responsiveness during IPPV. For the same V t, if chest wall compliance is reduced, then ITP will increase for a constant V t increasing both PPV and SVV. Accordingly, it is the change in ITP, not the change in V t, during IPPV that determines PPV and SVV. These findings are in agreement with our previous findings that the primary determinant of ventilation-associated changes in VR [18] and RV output [19] was the change in ITP during ventilation. This finding has special relevance in the management of clinical situations such as abdominal hypertension (IAH), where massive fluid resuscitation should be avoided. The current PPV and SVV thresholds used to drive resuscitation algorithms might lead to inappropriate (non preload-responsive) and potentially deleterious fluid expansion if IAH is present. Until clinical trials examine this point specifically, caution should be used when using PPV or SVV to drive resuscitation in the setting of IAH. Accordingly, PPV and SVV as predictors of fluid response need to be interpreted in light of both the tidal volume and chest wall compliance. If chest wall compliance decreases, then for the same tidal volume and degree of volume responsiveness, both PPV and SVV will increase.

Finally, our data agree with previous observations that the magnitude of PPV and SVV decrease as contractility decreases [4, 5]. Still, under both baseline and AVF conditions, systolic and PP are higher during inspiration, though during control there is an associated expiratory decrease in SV and PP (Fig. 3). These data are consistent with our previous study [1] which documented that increasing ITP augments SVLV in heart failure but only causes SVLV to decrease in control conditions, owing to its associated decrease in RV filling. Thus, one needs to examine the phase of the PP and SV change relative to ventilation as well as its magnitude in order to ascertain its etiology. Potentially, one will see an increase in SVV in heart failure if associated with a stiff chest wall and large tidal volumes. However, as shown in Fig. 3, the increases will occur during inspiration, not expiration, as is usually seen. Accordingly, if PPV and SVV are being used to drive fluid resuscitation, attention needs to be focused on the phase relation between airway pressure and the maximal PP. If the increase in airway pressure precedes the increase in PP, then the subject may be inferred to be volume responsive. However, if the increase in airway pressure and PP coincide then caution needs to be used with giving additional fluid, as this relation may also be seen in severe heart failure.

Study limitations

Our study has several technical limitations. First, we used anesthetized canine preparation without lung pathology or anemia. The vascular responsiveness and contractile reserve of the dog are greater than those of humans and may have masked or exaggerated the responses we report. In support of that assumption, the PPV and SVV values we report are higher than those usually seen in humans. Second, our reduced sample size limits our ability to find real statistically significant differences. Although statistical significance may not have been achieved in the small number of animals the physiological implications of these findings retain clinical relevance because they display similar trends to prior studies done in less well-defined and less accurately measured scenarios of clinical care [8, 9, 12, 16, 17]. Third, we did not measure ITBV, but only the dynamic differences in SVRV and SVLV and inferred that these differences reflected changes in the blood pool between them. This analysis though accurate for noting trends in ITBV, and used by us previously, does not allow for the estimation of total ITBV which may vary widely under the different experimental conditions of the study. Fourth, we measured arterial pressure at the aortic level using a high fidelity catheter. However, in clinical practice PP and PPV are measured peripherally. Peripheral PP is higher than the aortic PP because of the pulse wave amplification phenomenon [11]. In addition, SVLV and SVV measured using arterial pressure waveform analysis can differ from SVLV and SVV measured using aortic flow probe. Therefore, the relationship between PP and SVLV and between PPV and SVV may differ at the peripheral level from what we report. Fifth, although our study unmasks the limits of the currently used thresholds of PPV and SVV, it does not allow us to ascertain why ITBV and V t changes directly cause PPV and SVV to vary, as both LV preload and afterload are simultaneously altered. Note that during thoraco-abdominal binding, systolic arterial pressure increased with inspiration independent of changes in SVLV. Still, PP and SVLV remained coupled (Fig. 3). Furthermore, we did not cross-validate the relation between PPV or SVV and volume responsiveness using a fluid challenge. Although that validation was done before, the threshold values for fluid responsiveness will vary with changes in V t and chest wall compliance. Still, our data demonstrate that the ability of both PPV and SVV parameters to predict volume responsiveness will be a function of changing chest wall compliance and tidal volume. Finally, trends in PPV or SVV in response to disease, time, and therapy remain the most relevant use of these new hemodynamic parameters.

References

Pinsky MR, Matuschak GM, Klain M (1985) Determinants of cardiac augmentation by increases in intrathoracic pressure. J Appl Physiol 58:1189–1198

Michard F, Teboul JL (2002) Predicting fluid responsiveness in ICU patients: a critical analysis of the evidence. Chest 121:2000–2008

Pinsky MR (2004) Using ventilation-induced aortic pressure and flow variation to diagnose preload responsiveness. Intensive Care Med 30:1008–1010

Michard F, Boussat S, Chemla D, Anguel N, Mercat A, Lecarpentier Y, Richard C, Pinsky MR, Teboul JL (2000) Relation between respiratory changes in arterial pulse pressure and fluid responsiveness in septic patients with acute circulatory failure. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 162:134–138

Reuter DA, Felbinger TW, Schmidt C, Kilger E, Goedje O, Lamm P, Goetz AE (2002) Stroke volume variation for assessment of cardiac responsiveness to volume loading in mechanically ventilated patients after cardiac surgery. Intensive Care Med 28:392–398

De Backer D, Heenen S, Piagnerelli M, Koch M, Vincent JL (2005) Pulse pressure variations to predict fluid responsiveness: influence of tidal volume. Intensive Care Med 31:517–523

Denault AY, Gasior TA, Gorcsan J, Mandarino WA, Deneault LG, Pinsky MR (1999) Determinants of aortic pressure variation during positive-pressure ventilation in man. Chest 116:176–186

Gunn SR, Harrigan PWJB, Denault AY, Gorcsan J III, Teboul JL, Pinsky MR (2002) Does pulse pressure variation correlate with conventional measures of preload? Crit Care Shock 5:170–176

Kim HK, Pinsky MR (2008) Effect of tidal volume, sampling duration, and cardiac contractility on pulse pressure and stroke volume variation during positive-pressure ventilation. Crit Care Med 36:2858–2862

Boltwood CM, Appleyard RF, Glantz SA (1989) Left ventricular volume measurement by conductance catheter in intact dogs. Circulation 80:1360–1377

Lopes MR, Oliveira MA, Pereira VOS, Lemos IPB, Auler JOC Jr, Michard F (2005) Goal-directed fluid management based on pulse pressure variation monitoring during high-risk surgery: a pilot randomized controlled trial. Crit Care 11:R100–R107

Pinsky MR, Summer WR, Wise RA, Permutt S, Bromberger-Barnea B (1983) Augmentation of cardiac function by elevation of intrathoracic pressure. J Appl Physiol 54:950–955

Michard F, Chemla D, Richard C, Wysocki M, Pinsky MR, Lecarpentier Y, Teboul JL (1999) Clinical use of respiratory changes in arterial pulse pressure to monitor the hemodynamic effects of PEEP. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 159:935–939

Slama M, Masson H, Teboul JL, Arnould ML, Nait-Kaoudjt R, Colas B, Peltier M, Tribouilloy C, Susic D, Frohlich E, Andrejak M (2004) Monitoring of respiratory variations of aortic blood flow velocity using esophageal Doppler. Intensive Care Med 30:1181–1187

Michard F (2005) Changes in arterial pressure during mechanical ventilation. Anesthesiology 103:419–428

Muller L, Louart G, Bousquet PJ, Candela D, Zoric L, de La Coussaye JE, Jaber S, Lefrant JY (2010) The influence of the airway driving pressure on pulsed pressure variation as a predictor of fluid responsiveness. Intensive Care Med 36:496–503

Monge García MI, Gil Cano A, Gracia Romero M (2011) Dynamic arterial elastance to predict arterial pressure response to volume loading in preload-dependent patients. Crit Care 15(1):R15

Pinsky MR (1984) Instantaneous venous return curves in an intact canine preparation. J Appl Physiol 56:765–771

Pinsky MR (1984) Determinants of pulmonary artery flow variation during respiration. J Appl Physiol 56:1237–1245

Conflict of interest

None for any author.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

This study was supported in part by NIH award HL067181.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Mesquida, J., Kim, H.K. & Pinsky, M.R. Effect of tidal volume, intrathoracic pressure, and cardiac contractility on variations in pulse pressure, stroke volume, and intrathoracic blood volume. Intensive Care Med 37, 1672–1679 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-011-2304-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-011-2304-3