Abstract

Maternal infections are a risk factor for preterm birth (PTB); 40% to 50% of PTBs are estimated to result from infection or inflammation. Higher infection rates are reported in low- and middle-income countries (LMIC), and over 80% of PTBs occur in these settings. Global literature was synthesised to identify infections whose prevention or treatment could improve maternal and neonatal health outcomes and/or prevent mother-to-child transmission of infections.

Best evidenced risk factors for PTB were maternal infection with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) (OR2.27; 95%CI: 1.2–4.3), syphilis (OR2.09; 95%CI:1.09–4.00), or malaria (aOR3.08; 95%CI:1.2–4.3). Lower certainty evidence identified increased PTB risk with urinary tract infections (OR1.8; 95%CI: 1.4–2.1), sexually transmitted infections (OR1.3; 95%CI: 1.1–1.4), bacterial vaginosis (aOR16.4; 95%CI: 4.3–62.7), and systemic viral pathogens.

Routine blood testing and treatment are recommended for HIV, hepatitis B virus, and syphilis, as well as for malaria in areas with moderate to high transmission. In high-risk populations and asymptomatic or symptomatic disease, screening for lower genital tract infections associated with PTB should be offered at the antenatal booking appointment. This should inform early treatment and management. Heath education promoting pre-pregnancy and antenatal awareness of infections associated with PTB and other adverse pregnancy outcomes is recommended.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 Background

Infection is a major risk factor for PTB, accounting for 40–50% of all deliveries before 37 completed weeks of gestation. The most common route of infection is via the genital tract and subsequent microbial ascension and invasion of the amniotic cavity (25–40% of the total number of PTBs) [1,2,3,4]. Routine ANC provides an opportunity for health-care professionals to assess a pregnant woman’s risk of PTB and other adverse pregnancy outcomes. High rates of maternal bacterial and viral infections are reported in LMICs, and it is in these settings where most PTBs occur (approximately 81%) [5].

2 Evidence Statement

Infection in pregnancy is associated with an increased risk of PTB. Current guidelines recommend routine testing and treatment for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), hepatitis B virus, malaria (context dependent), and syphilis. The aim of this testing is to improve health outcomes of mothers and their babies and/or to prevent mother-to-child transmission.

The increased risk of PTB from other infections such as asymptomatic bacteriuria (ASB) should prompt testing a clean-catch midstream urine by microscopy, culture, and sensitivity, where available, and providing antibiotic treatment as appropriate. Pregnant women should be offered testing for lower genital tract infections in high-risk populations or cases of suspected disease, with or without symptoms, as evidence has shown that such treatment decreases PTB risk.

3 Synopsis of Best Evidenced Infectious Risk Factors for Preterm Birth

For a summary of the evidence of infectious risk factors for preterm birth, please see Table 1, in Sect. 5.

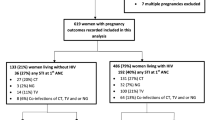

3.1 Human Immunodeficiency Virus

HIV is more prevalent in LMIC than HIC settings. HIV has been shown to increase the risk of spontaneous PTB 2.1-fold when compared to HIV-negative controls (17% vs. 8%; OR 2.27; 95% CI:1.2–4.3). Furthermore, a 3.2-fold increased risk for PTB was reported in HIV-positive women, and this was strongly associated with the use of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) in the second trimester, OR 6.2 (95% CI:1.4–26.2) [6].

3.2 Malaria

Malaria infection is a risk factor for PTB. A systematic review and meta-analysis of 58 studies with 134,801 participants across 21 East African countries reported increased risks of PTB (aOR of 3.08 (95% CI:1.2–4.3) and also when malaria is a co-infection with HIV (aOR 2.59; 95% CI:1.84–3.66) [8]. Intermittent preventive treatment of malaria in pregnancy (IPTp) is an integral part of antenatal care in areas with moderate to high malaria transmission, alongside use of long-lasting insecticidal nets (LLINs), prompt diagnosis, and effective treatment of malaria infections.

3.3 Syphilis

Infection with syphilis-causing bacteria, Treponeda pallidum, is more common in LMIC than HIC settings. Syphilis is associated with an increased risk of PTB where mothers present late to antenatal care (OR 2.09; 95% CI:1.09–4.00) [9].

3.4 Urinary Tract Infections (UTI)

UTIs are frequently reported as a risk factor for PTB, with studies stating odds ratios (OR) of 1.8 (95% CI: 1.4–2.1) [10], 1.8 (95% CI: 1.3–2.4) [11] and 5.05 (95% CI: 1.16–21.8) [12, 13]. Low quality evidence from a systematic review and meta-analysis conducted across 21 East African countries reported an OR of 5.27 (95% CI: 2.98–9.31) [8]. Symptomatic urinary tract infections should be treated with antibiotics, and repeated urine testing is advised in low- and high-risk women [8].

3.5 Asymptomatic Bacteriuria (ASB)

Many infections during pregnancy present subclinically or are asymptomatic, subsequently delaying treatment and diagnosis. Untreated ASB is associated with PTB (aOR 1.6; 95% CI: 1.5–1.7) and has been shown to develop into acute pyelonephritis, itself an independent risk factor for PTB (OR: 2.6; 95% CI: 1.7–3.9) [7, 14, 26]. Increased rates of spontaneous PTB in patients with pyelonephritis have been reported (10.3% vs 7.9%; OR:1.3; 95% CI:1.2–1.5) [27]. Routine urine dipstick testing is not advised by the WHO due to high false-positive rates (118/1000) leading to unnecessary treatment and antimicrobial resistance [7].

3.6 Sexually Transmitted Infections (STIs)

STIs of the lower genital tract have been linked to increased risk of PTB; the most robust evidence available reports an OR of 1.3 (95% CI:1.1–1.4) [17] in cases of trichomoniasis (caused by the Trichomonas vaginalis parasite). However, Gulmezoglu and Azhar (2011) reported T. vaginalis treatment with metronidazole to appear to increase risk of PTB (RR 1.78; 95%CI:1.19 to 2.66) [21, 28]. Odds ratios of 2.2 (95% CI:1.03–4.78) and 3.2 (95% CI:1.08–9.57) at <37 weeks delivery and < 35 weeks delivery, respectively, are reported where infection with Chlamydia trachomatis bacteria has been diagnosed [18, 19].

3.7 Bacterial Vaginosis (BV)

A 2014 prospective cohort study found a significant increase in PTB risk in women with higher levels of BV-associated bacteria and a previous history of PTB, adjusted OR (aOR) 16.4 (95% CI: 4.3–62.7) [22]. Strategies to treat BV have failed to lower PTB risk [4].

3.8 Systemic Viral Pathogens

Infection with some systemic viral pathogens is a risk factor for PTB; the available best evidence reports odds ratios for cytomegalovirus (CMV), 1.6 (95% CI:1.14–2.27) [24], any herpesvirus, 1.51 (95% CI:1.08–2.10) [24], and influenza A (H1N1), 2.21 (95% CI:1.47–3.33) [25].

3.9 Factors Not Yet Shown to Be Associated with Increased Risk of Preterm Birth

-

A systematic review and meta-analysis including one study of periodontal disease (PD) carried out in East Africa reported it as a risk factor for PTB (aOR 2.32; 95% CI:1.33–4.35) [8]. Currently, there is insufficient evidence to directly establish a connection between PTB and periodontal infection [4].

-

There is limited evidence suggesting infection by Neisseria gonorrhoea bacteria as a risk factor for PTB (OR 2.50; 95% CI:1.39–4.50) [19].

-

Estimations of global burden of tuberculosis (TB) found little evidence of increased risk of PTB in TB-infected pregnant women [29].

-

Colonisation by Group B Streptococcus (GBS) has previously been described as a risk factor for PTB; a 1989 meta-analysis found non-bacteriuric patients had half the risk of PTB as those with ASB resulting from GBS colonisation (RR 0.5; 95% CI:0.36–0.70) [30]; however, more recent evidence is lacking.

4 Practical Clinical Risk Assessment Instructions for PTB

Health-care workers conducting the antenatal booking assessment should determine the risk of infections linked to PTB. This enquiry should determine likelihood of specific infections known to be risk factors for PTB to inform testing and management as follows:

-

Urinary tract infections (UTI): UTIs and progression to pyelonephritis are risk factors for PTB. Information on frequency of urination and presence of dysuria or suprapubic pain should be sought. Point of care dipstick testing should be undertaken where symptomatic bacteriuria is suspected.

-

Pyelonephritis: Along with determining symptoms of a UTI, detail of any fever or loin pain should also be elicited where pyelonephritis is suspected.

-

Asymptomatic bacteriuria (ASB): A urine specimen, preferably a clean catch urine (CCU) specimen, should be collected from all women at the antenatal booking clinic. Where not feasible, a midstream urine (MSU) specimen will suffice. Dipstick testing should not be performed due to a lack of sensitivity. CCU/MSU should be sent to the laboratory for culturing.

-

Bacterial vaginosis (BV): Routine screening is not recommended for asymptomatic BV. Symptomatic BV information should be elicited through asking pregnant women about any changes to odour or consistency of vaginal discharge and/or vaginal itching.

-

Syphilis, HIV, and hepatitis B: Routine blood testing should be offered to all women at the booking clinic for syphilis, HIV, and hepatitis B. Both syphilis and HIV have been shown to be risk factors for PTB.

Enquiries and testing, where appropriate, should lead to categorisation of risk of PTB and appropriate treatment and management.

5 Interventions for Evidenced Risk Factors for PTB

The evidenced effective interventions to address infections associated with preterm birth are shown in Table 1.

6 Summary of ANC Infection Interventions to Reduce PTB

These are depicted in Table 2.

7 Research and Clinical Practice Recommendation

Clinical practice should focus on promoting awareness of infections prior to and during pregnancy rather than routine testing of all infections linked to PTB. Further research is required to consider routine testing for chlamydia in target populations and effectiveness of dipstick testing for ASB in LMIC settings.

References

Witkin SS. The vaginal microbiome, vaginal anti-microbial defence mechanisms and the clinical challenge of reducing infection-related preterm birth. Bjog-an International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2015;122(2):213–8.

Leiby JS, McCormick K, Sherrill-Mix S, Clarke EL, Kessler LR, Taylor LJ, et al. Lack of detection of a human placenta microbiome in samples from preterm and term deliveries. Microbiome. 2018;6

Sebire NJ. Implications of placental pathology for disease mechanisms; methods, issues and future approaches. Placenta. 2017;52:122–6.

Nadeau HCG, Subramaniam A, Andrews WW. Infection and preterm birth. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med. 2016;21(2):100–5.

Chawanpaiboon S, Vogel JP, Moller A-B, Lumbiganon P, Petzold M, Hogan D, et al. Global, regional, and national estimates of levels of preterm birth in 2014: a systematic review and modelling analysis. The Lancet Global health. 2018.

Lopez M, Figueras F, Hernandez S, Lonca M, Garcia R, Palacio M, et al. Association of HIV infection with spontaneous and iatrogenic preterm delivery: effect of HAART. AIDS. 2012;26(1):37–43.

World Health Organisation. WHO Recommendations on Antenatal Care for a Positive Pregnancy Experience. 2016;ISBN 978 92 4 154991 2.

Laelago T, Yohannes T, Tsige G. Determinants of preterm birth among mothers who gave birth in East Africa: systematic review and meta-analysis. Ital J Pediatr. 2020;46(1):14.

Hawkes SJ, Gomez GB, Broutet N. Early antenatal Care: does it make a difference to outcomes of pregnancy associated with syphilis? A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2013;8(2)

Schieve LA, Handler A, Hershow R, Davis F. Urinary tract infection during pregnancy–its association with maternal morbidity and perinatal outcome. Am J Public Health. 1994;84(3):405–10.

Qobadi M, Dehghanifirouzabadi A. Urinary tract infection (UTI) and its association with preterm labor: findings from the Mississippi pregnancy risk assessment monitoring system (PRAMS), 2009–2011. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2015;2(1):1577.

Pandey K, Bhagoliwal A, Gupta N, Katiyar G. Predictive value of various risk factors for preterm labour. J Obstet Gynecol India. 2010;60:141–5.

Baer RJ, Bandoli G, Chambers BD, Chambers CD, Oltman SP, Rand L, et al. Risk of preterm birth among women with a urinary tract infection by trimester of pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019;220(1):S433–S4.

Sheiner E, Mazor-Drey E, Levy A. Asymptomatic bacteriuria during pregnancy. Journal of Maternal-Fetal & Neonatal Medicine. 2009;22(5):423–7.

Angelescu K, Nussbaumer-Streit B, Sieben W, Scheibler F, Gartlehner G. Benefits and harms of screening for and treatment of asymptomatic bacteriuria in pregnancy: a systematic review. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2016;16

Smaill FM, Vazquez JC. Antibiotics for asymptomatic bacteriuria in pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;8

Cotch MF, Pastorek JG, Nugent RP, Hillier SL, Gibbs RS, Martin DH, et al. Trichomonas vaginalis associated with low birth weight and preterm delivery. Sex Transm Dis. 1997;24(6):353–60.

Andrews WW, Goldenberg RL, Mercer B, Iams J, Meis P, Moawad A, et al. The preterm prediction study: association of second-trimester genitourinary chlamydia infection with subsequent spontaneous preterm birth. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000;183(3):662–8.

Rours G, Duijts L, Moll HA, Arends LR, de Groot R, Jaddoe VW, et al. Chlamydia trachomatis infection during pregnancy associated with preterm delivery: a population-based prospective cohort study. Eur J Epidemiol. 2011;26(6):493–502.

Vuylsteke B. Syndromic approach–current status of syndromic management of sexually transmitted infections in developing countries. Sex Transm Infect. 2004;80(5):333–4.

Gülmezoglu AM, Azhar M. Interventions for trichomoniasis in pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;5

Nelson DB, Hanlon A, Nachamkin I, Haggerty C, Mastrogiannis DS, Liu CZ, et al. Early pregnancy changes in bacterial vaginosis-associated bacteria and preterm delivery. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2014;28(2):88–96.

Okun N, Gronau KA, Hannah ME. Antibiotics for bacterial vaginosis or trichomonas vaginalis in pregnancy: a systematic review. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105(4):857–68.

Gibson CS, Goldwater PN, MacLennan AH, Haan EA, Priest K, Dekkera GA, et al. Fetal exposure to herpesviruses may be associated with pregnancy-induced hypertensive disorders and preterm birth in a Caucasian population. Bjog-an Int J Obstet Gynaecol. 2008;115(4):492–500.

Doyle TJ, Goodin K, Hamilton JJ. Maternal and Neonatal Outcomes among Pregnant Women with 2009 Pandemic influenza a(H1N1) illness in Florida, 2009-2010: a population-based cohort study. PLoS One 2013;8(10).

Farkash E, Weintraub AY, Sergienko R, Wiznitzer A, Zlotnik A, Sheiner E. Acute antepartum pyelonephritis in pregnancy: a critical analysis of risk factors and outcomes. European Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology and Reproductive Biology. 2012;162(1):24–7.

Wing DA, Fassett MJ, Getahun D. Acute pyelonephritis in pregnancy: an 18-year retrospective analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2014;210(3)

Kigozi GG, Brahmbhatt H, Wabwire-Mangen F, Wawer MJ, Serwadda D, Sewankambo N, et al. Treatment of trichomonas in pregnancy and adverse outcomes of pregnancy: a subanalysis of a randomized trial in Rakai, Uganda. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;189(5):1398–400.

Sugarman J, Colvin C, Moran AC, Oxlade O. Tuberculosis in pregnancy: an estimate of the global burden of disease. Lancet Global Health. 2014;2(12):E710–E6.

Romero R, Oyarzun E, Mazor M, Sirtori M, Hobbins JC, Bracken M. Meta-analysis of the relationship between asymptomatic bacteriuria and preterm delivery low birth weight. Obstet Gynecol. 1989;73(4):576–82.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2022 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Parris, K.M., Jayasooriya, S.M. (2022). Prenatal Risk Assessment for Preterm Birth in Low-Resource Settings: Infection. In: Anumba, D.O., Jayasooriya, S.M. (eds) Evidence Based Global Health Manual for Preterm Birth Risk Assessment . Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-04462-5_5

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-04462-5_5

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-031-04461-8

Online ISBN: 978-3-031-04462-5

eBook Packages: MedicineMedicine (R0)