Abstract

Academic misconduct is a growing concern within Canadian higher education and around the world. Research suggests that university faculty have an extensive history of addressing academic misconduct, with an increased focus on detection and prevention. There has been little research, however, on faculty teaching in community colleges and their experiences with reporting and prevention, particularly within the Canadian context. As concern with academic misconduct continues to rise, we suggest that there needs to be more focus on these issues, particularly with respect to approaches that support a cultural shift with faculty that encompasses the fundamental values of academic integrity. For this to occur, it is essential for educational institutions to understand the forces that influence potential dishonest behaviors among students, create policies to address and support academic integrity, while creating a culture of academic integrity which supports both faculty and students alike. Faculty play a crucial role in creating environments that expound and uphold the values of academic integrity. Faculty are the frontline contact, espousing the values and expectations of their institution to students, monitoring, and reporting. Our scholarship of teaching and learning (SoTL) research was motivated by the aim to help community college faculty address the issue of academic misconduct within their classrooms and institutional environments. Barriers to reporting academic dishonesty, identified by faculty, include time and workload in reporting, a perceived lack of institutional support from administration and applicable institutional policies, as well as the perceived threat felt by faculty in reporting incidents.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

Introduction

The purpose of this chapter is to provide an understanding of the challenges and barriers perceived by faculty teaching within community colleges in Canada in identifying and responding to incidences of academic misconduct. Community colleges within Canada have a long-standing history of providing publicly funded, open-access educational programs; an education-for-all approach supporting individuals' edifying and workforce training needs. While programming varies from province to province and amongst institutions, the prevalence of academic misconduct remains a universal phenomenon. This is in part due to the complex nature of academic integrity and ambiguous roles in the ownership of and responsibility for upholding institutional cultures of integrity (Gottardello & Karabag, 2020).

As much of the literature examines this phenomenon from the lens of student responsibility, there is a gap in understanding faculty responsibilities for teaching and upholding the principles of academic integrity, particularly within Canadian community colleges. This chapter addresses this gap, presenting findings from our research on the perceived barriers identified by faculty in reporting academic misconduct. These hindrances include time and workload involved in reporting incidents; perceived lack of support by senior administration; faculty's lack of awareness of institutional policies related to academic integrity; and the perceived threats to faculty if they choose to report incidents.

It is essential to understand the faculty perspective within the community college environment and perceived barriers in order to provide appropriate and adequate support to address these impediments. This chapter will offer ways in which community colleges and, by extension, all post-secondary institutions can better equip their faculty to understand, communicate, teach, and uphold the fundamental principles of academic integrity; honesty, trust, respect, responsibility, and courage (International Center for Academic Integrity [ICAI] 2021). This includes advocating for clear and concise academic policies, professional development for faculty around an array of topics, and advocating for faculty support and resources.

We write this chapter wearing many hats. According to Eaton (2021), addressing academic integrity issues requires a multi-stakeholder approach. At the community college level, we work comfortably within the 4M Framework (Kenny & Eaton, 2022). At the micro level, we both have taught within nursing education for a combined total of over 30 years. We have seen many instances of academic integrity violations in the classroom including plagiarism, cheating on exams and projects, and contract cheating. Furthermore, we have seen instances of dishonesty in the clinical setting such as falsifying documents and assessments. We understand first-hand that faculty struggle with how to detect and whether to report academic integrity violations.

Wolsky has previously been the academic chair for the School of Health Sciences and Allied Health programs as well as the Bachelor of Nursing program where she was responsible to monitor and report academic integrity violations. She currently teaches within the Bachelor of Nursing program, working alongside faculty, and advocating for a culture of academic integrity. Hamilton is an educational developer and currently works at the meso level in the Centre for Teaching and Learning as the academic integrity lead. Along with a team, Hamilton ensures there is professional development for all college employees who teach and support students, related to academic integrity. We understand the barriers to reporting academic dishonesty as we have worked side by side with the faculty who have identified them. We chose to complete a scholarship of teaching and learning (SoTL) research project on academic integrity as “developing personal and informal networks of support is essential for supporting academic integrity” (Eaton, 2021, p. 77) in addition to the outcomes of the study.

Background

Despite faculty efforts to encourage students not to engage in academic misconduct, evidence suggests that academic misconduct remains rampant in higher education and is a growing concern on college and university campuses worldwide (Christensen Hughes & McCabe, 2006; Madara & Namango 2016). The continued advancement of technology-assisted educational practices has contributed to the continuing rise of academic misconduct (Anney & Mosha, 2015; Bristor & Burke, 2016) and while software for detecting plagiarism can help ease the burden of verifying referenced material, it is costly and not available at all educational institutions (Anney & Mosha, 2015). This has left faculty feeling frustrated and discouraged, as they attempt to stay one step ahead of new and innovative cheating methods (DiBartolo & Walsh, 2010).

Academic integrity polices are one-way institutions can address this emergent issue as part of a systemic approach. Bretag et al. (2011) undertook an analysis of 39 Australian universities' academic integrity policies to identify exemplar policies. This was done under the supposition that “a culture of academic integrity is central to all aspects of policy and practice” (p. 2). Additional research studies identified that even though institutional policies related to academic integrity exist, faculty are often reluctant to adhere to these policies (Bertram Gallant, 2008; Bertram Gallant & Drinan 2006) or choose at their discretion, a variety of ways in which to address the situation (Bristor & Burke, 2016). This may include a formal code of conduct reprimand, a one-on-one teaching opportunity with or without official reporting, or a chance to redo the assessment (Keener et al., 2019).

McCabe (1993) was one of the first authors to explore faculty reactions to suspected incidents of academic misconduct. He found that faculty were reluctant to report academic integrity violations formally, preferring instead to handle violations one-on-one, and depending on the severity of the event, give students a warning. Unfortunately, over 30 years later, faculty remain reluctant to address and report incidents of student academic misconduct. The International Centre for Academic Integrity (ICAI) espouses that academic integrity should be a fundamental component in education and is foundational in preparing students to succeed (ICAI, 2021). Whether students intentionally or unintentionally engage in unethical academic behavior, it is most often left to front-line faculty to educate and monitor students' academic activities. So why are faculty so resistant to report these incidents?

Faculty are concerned that reporting academic misconduct may negatively affect their employment in terms of professional reputations, application for tenure, and anxious whether their fellow peers would support them through the reporting process (Fontana, 2009; Tayan, 2017) in additional to potential litigation by the student. Faculty experience significant anxiety and stress related to the physiological discomfort experienced in reporting a student. They fear receiving poor student evaluations and are concerned with potentially damaging relationships with future students (Blau et al., 2018; Christensen Hughes & McCabe, 2006; Keith-Spiegel et al., 2010; Thomas, 2017).

The time required in reporting and attending a hearing is also perceived as a deterrent to reporting. Faculty are unenthusiastic to take on the enormous burden of reporting acts of academic misconduct, as faculty who had previously reported such incidents seemed unwilling to go through the arduous process again in the future (Eaton et al., 2020; Keith-Spiegel et al., 2010; Thomas 2017). According to Schneider (1999), a heavy teaching workload is one of the main reasons' faculty chose not to report academic misconduct. Grading huge volumes of scholarly papers can be daunting, without the onerous task of checking each student's references for acts of plagiarism.

The culture of academic integrity within the community college setting has been minimally explored within the literature but does present its own unique challenges. Many faculty hired by community colleges are employed on a short-term, contractual (hourly) basis. They are often employed elsewhere as well, resulting in an emotional and ethical detachment from the students and the institution (Bertram Gallant, 2018). Faculty hired to teach within community colleges often come from the industry in which they have been hired to teach—trades, policing, healthcare, agriculture—and do not have formal training related to teaching and learning. Contractual faculty also receive minimal orientation to the role of teacher, related explicitly to academic policies (Crossman, 2019) and may not feel adequately supported, or feel they have the required tools or knowledge to minimize cheating within their classroom (Garza Mitchell & Parnther, 2018). In addition, educational programs within community colleges are often short in duration; students can complete their program in under a year, providing faculty minimal time to cultivate professional, ethical practices in their students.

Context: Comprehensive Community Colleges and Academic Integrity

We situated our work within the Canadian community college context. Specifically, both educational institutions that participated in this study were from the province of Alberta. The Alberta post-secondary landscape has six publicly funded post-secondary institutions. The context of our research took place in the Comprehensive Community College (CCC) environment. According to the Alberta Government (n.d.), CCCs are responsible for preparing students for work in industry or providing them with the education needed for admission into other post-secondary programs. Comprehensive Community Colleges offer programming which includes academic upgrading, apprenticeship training programs, certificate and diploma programs, as well as some undergraduate degree programs. Comprehensive Community Colleges operate independently of one another but will often collaborate with other post-secondary institutions. Faculty who teach within CCC environments are expected to follow institutional policies and procedures.

Policies and Procedures

The literature provides information on developing effective policies and procedures (Clark et al., 2020; Stoesz et al., 2019). Many researchers and advocates of academic integrity suggest that it is essential for educational institutions to understand the motivations for academic misconduct, to create policies that address, enforce, and educate students and faculty, and to develop a culture of academic integrity which both faculty and students can understand and support (Orr, 2018; Shane et al., 2018). Institutional policies alone cannot address this complex issue. Instead as Morris (2018) explains, a “multi-pronged strategy is required for higher education institutions to promote and support academic integrity and effectively address its ‘shadow’—student academic misconduct, particularly plagiarism, collusion, and contract cheating” (p. 2). Institutional policies on academic integrity should help guide students to adhere to the ICAI's six fundamental values, as students in post-secondary education are learning to develop their own moral compasses (ICAI, 2021; McCabe et al., 2012). Orr (2018) suggests that post-secondary faculty play a critical role by teaching their students values, including honesty and academic integrity, while schooling them on what constitutes academic misconduct and potential consequences.

Institutional Policies Are Imperative

Even though institutional policies and procedures that address academic integrity are essential, more is still needed. Stoesz et al. (2019) explain that “educational organizational policies are formal statements of principle that are used to establish boundaries, provide guidance, and outline best practices for educational institutions and should support their mission and values” (p. 1). Senior leaders need to explicitly demonstrate their support, reminding faculty about institutional policies on academic integrity, the expectation that they are followed, where to find the policies, and how to apply them. As noted in the work of Bretag and Harper (2017, slide #20), an institution-wide, holistic, and systemic approach is needed in addressing issues of academic integrity.

Academic policies are just one component of an institutional academic integrity strategy that includes supporting faculty and students. Proponents of such strategies suggest that programming should have an educational emphasis and should consist of topics and activities around professional development for all employees on academic integrity and misconduct (Bretag & Mahmud, 2016; Morris, 2018; Morris & Carroll, 2016). The topic of integrity should furthermore be woven into events such as “student recruitment, orientation and induction; policy and procedures, teaching and learning practices, working with students, the professional development of staff; and the use of technology” (Bretag & Harper, 2017, pp. 2–3).

Scholarship of Teaching and Learning Research Design

-

Why do faculty within community colleges not report acts of known academic dishonesty among students?

-

What perceived barriers exist to faculty in reporting acts of academic dishonesty among students?

Method

The overall aim of this study was to gain a better perspective of barriers perceived by faculty teaching at community colleges in reporting incidents of academic misconduct. Additionally, we explored to what extent faculty are reporting incidents of academic misconduct and influences impacting their decision to report or not report. We chose to situate our research from an interpretive lens, giving credence to the faculty's subjective experience and the institutional context wherein it occurred.

Data Collection

A quantitative non-experimental survey design was used, administered as an online digital distribution through Fluidsurvey. Our data collection tool included twenty-four questions using a five-point Likert-Scale questionnaire. Four of the questions allowed open-ended responses, so participants could give examples to support their answers. Participating institutions included two mid-sized community colleges from Alberta, Canada. An email communication inviting participation was distributed to all faculty at each institution via the faculty listserv. This included full-time and part-time continuing, term-certain, and contact (hourly) faculty (sometimes referred to as sessional). The email message provided information on assuring anonymity and contact information for the researchers.

Limitations

Limitations of the research study included using only two community colleges within Alberta, Canada. The findings in this study may not be generalizable to community colleges across Alberta or Canada. In addition, institutional culture at community colleges varies to that at research intensive universities (RIU), so we acknowledge faculty experiences between the two types of institutions may vary.

Results and Findings

We had a response rate of approximately 20% (n = 101), with 56 females and 44 males (1 response gender not indicated). Additional demographic information collected included the highest level of completed formal education (Table 24.1) and, years teaching in post-secondary education (Table 24.2).

Additional demographic information included which discipline of teaching was the respondent's primary area of instruction. The initial question included all programming areas among the two community colleges involved in the study. The data were then collated into five major academic disciplines as seen in Table 24.3.

While there is a breadth of literature on what faculty perceive as constituting academic misconduct and how faculty choose to address these events, there is less available literature on the barriers faculty face when trying to report, especially within the Canadian Comprehensive Community College context. While a significant percentage of participants identified that they would always report misconduct occurrences (24%), the remaining participants identified a plethora of reasons as to why they would not report.

We utilized an inductive approach to the coding the responses to the open-ended questions within the survey as we wanted the participants responses to determine the themes. From the open-ended questions in the survey the following four overarching themes emerged: time, knowledge, support, and fear. Figure 24.1, utilizing the sketchnote method, presents a visual representation of the four themes identified.

Discussion

For the purpose of the chapter, we have summarized the results of the open-end responses at a high level. It is our intention to use our initial findings to develop a second research project using a qualitative semi-structured interview approach to delve more deeply into participants views on community college faculty's perceptions of barriers to reporting academic integrity violations.

The Four Overarching Themes

Theme One: Time

There was significant agreement among the participants that reporting student incidents was too time-consuming (15%). This included the amount of time it took to document the student's behavior, fill out the required forms, meet with the department heads, along with a general lack of time due to current teaching workload. This finding is congruent with existing literature (Bertram Gallant, 2018; Crossman, 2019; Thomas, 2017) in which both continuing and hourly contract faculty alike feel the encumbrance of time constraints. Crossman (2019) aligns with this view, recognizing that the extra time involved to address academic misconduct is not clearly identified within employment contracts, contributing to a culture of indifference.

Theme Two: Knowledge

An underlying assumption may be that all faculty are aware of intuitional academic policies and, as such, are able to act in accordance. Our findings identified that 14% of participants were unfamiliar with the institutional academic misconduct policies. This is consistent with other studies such as Eaton et al.'s (2020) study on the gap between institutional policy and educator practice in which 10.5% of respondents rated themselves as having a low understanding of their institution's policies on academic integrity. A lack of awareness around academic policies and institutional guidelines to assist faculty in dealing with transgressions can leave faculty feeling lost and unsupported (Crossman, 2019).

Theme Three: Support

To uphold the values, policies, and procedures of an institution, senior administration must be involved and supportive of faculty and students' alike. Otherwise, faculty will not engage in the process of reporting, with 19% of respondents identifying they felt a lack of support from their immediate senior supervisor. This can set a discerning tone of non-risk to students violating academic integrity policies. To ensure faculty hold students accountable, senior administration must also provide their accountability related to their assigned responsibilities (Bristor & Burke, 2016) and support faculty accordingly. Support for faculty should also be clearly enacted within the integrity policy to ensure practical supports are outlined and available (Bretag et al., 2011). A perceived lack of support by faculty of senior administration will deter reporting misconduct (Garza Mitchell & Parnther, 2018), inadvertently creating a culture of acceptance by faculty and students.

Theme Four: Fear

Overall, it seemed a sense of fear played a significant role in whether faculty reported academic misconduct. The fear felt by faculty encompassed several different aspects, including; fear of damaged relationships between the faculty member and their colleagues (9%); fear of negative impact from senior administration (8%); fear of negative student evaluations (6%); fear of confrontation (6%); fear of negative peer evaluations (4.5%); fear of verbal or physical assault by the student (4.5%); fear of damage to the relationship between student and the faculty member (4.5%); fear of damage to the faculty's reputation (4%); and fear of faculty losing their job (3%). These findings are substantiated by earlier research studies, ascertaining that faculty are fearful of repercussions if they identify and report incidents of academic misconduct (Crossman, 2019; Eaton et al., 2020; Keith-Spiegel et al., 1998).

While it is essential for community colleges to have comprehensive policies on academic integrity, it is equally important that faculty are aware of, understand the intricacies of the policy, and support a culture of integrity (Gottardello & Karabag, 2020). Faculty are key players who interact with students directly on a day-to-day basis and who are in the prime position to clearly communicate institutional expectations and policy information, including potential penalties (Bristor & Burke, 2016). Faculty's intrinsic beliefs regarding ethical and moral behaviors will influence how they choose to respond to incidents of academic misconduct. This can create a complicated situation on how to best respond to suspected incidents of academic misconduct.

Community College Faculty Profiles

From our research data, we developed three faculty profiles to clarify further the faculty's approach and position in how they identified they would handle academic misconduct among their students. These profiles were created based thematic analysis, and direct quotes have been included as further evidence. These typologies are useful in further understanding faculty's perspective and attitude in addressing academic misconduct.

Teaching Opportunity Faculty

Jane teaches classes that have a high number of international and ESL students. Jane has encountered several academic misconduct incidents this year already but has chosen not to report any of them. Instead, Jane feels that each of these incidents is a learning opportunity, thinks that none of her students are genuinely dishonest in their activities, and really wants each of them to graduate.

-

“Some ESL students bring their cultural norms to the college, and on such occasions, this becomes a teaching moment.”

-

“It is a teaching opportunity. I sit down with the student and discuss academic dishonesty and teach them how to maintain academic integrity.”

-

“Used the incident as an opportunity to engage the student and correct/direct on a better approach to school.”

Independent Faculty

Gurpreet is considered a senior faculty member, having taught in higher education for many years. Gurpreet chooses not to report incidents of academic misconduct but instead deals with it personally. This may result in a one-to-one conversation or a zero on the assignment. Gurpreet believes it is his responsibility to manage these incidents and not senior administration.

-

“Prefer to handle it my own way.”

-

“I dealt with the matter with the student redoing the assignment but did not report it.”

-

“Failed student on the assignment rather than report it.”

-

“Personal policy of handling first-time, minor offences myself.”

-

“I dealt with it myself, I didn't report it to my Chair.”

Fearful Faculty

Miya is passionate about the courses she teaches. She really enjoys the student interaction and works to make her classrooms fun. However, Miya believes that teaching and monitoring academic integrity are not her responsibility. She doesn't believe her students cheat or cheat intentionally. She wants them all to graduate and is afraid of what might happen if she does report.

-

“Unsure if student truly intended to be dishonest—gave the student the benefit of the doubt.”

-

“Want the students to graduate.”

-

“I wasn't 100% sure it happened and if I could prove it.”

-

“Fear for the students future: i.e. losing scholarships or not being accepted to a grad school of their choice.”

-

“Difficult to prove the dishonesty.”

-

“Was accused of contributing to the student attrition rate in the program by the Dean by making waves and taking action.”

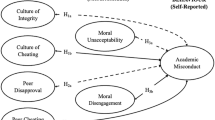

Recommendations

We have noted numerous challenges when discussing faculty barriers related to reporting academic misconduct. However, there are some recommendations that we suggest will assist faculty in addressing and overcoming these barriers. Key stakeholders must work collaboratively in upholding the integrity of the institution. A multifaceted approach is crucial in creating an institutional academic community that upholds the institutional academic standards while promoting and cultivating a moral and ethical society. The following recommendations encompass the three perspectives in which academic integrity is largely studied: from a teaching and learning standpoint, from a policy issue, and from a moral perspective (see Fig. 24.2).

Adapted from Student Perspectives on Plagiarism, by L. Adam, 2016, In T. Bretag (Ed.), Handbook of Academic Integrity (pp. 519–535) and Plagiarism: A Canadian Higher Education Case Study of Policy and Practice Gaps by S. E. Eaton et al., 2020, Alberta Journal of Educational Research, 66(4)

Conceptual lenses for academic integrity inquiry. Note

While there are several initiatives aimed at students, we will discuss supports and initiatives specifically focused on faculty, addressing the equated perceived barriers. In Fig. 24.3 we illustrate, via a sketchnote, there are many ways to assist faculty members and overcome these barriers. First and foremost, institutions must commit to creating a culture of integrity while supporting faculty in learning, upholding, and reporting academic misconduct. Each one of these aspects falls within each of the three conceptual lenses of academic integrity (see Fig. 24.2), intertwined and linked together, a multilayered approach.

Culture Change

Due to the very nature that cheating is so rampant in higher education, one could declare that higher education is inundated with a “cheating culture.” If not addressed, the culture of cheating will extend beyond the borders of higher education and into student's professional lives (Caldwell, 2010). Faculty have a responsibility to assist students in developing their moral compass. A culture change is not merely about developing or adopting honor codes for students, but rather it is about supporting and teaching students to always act with integrity. Clear academic policies need to be in place to support faculty and students alike to help cultivate a culture of integrity. These policies are most effective, as identified by Stoesz and Eaton (2020), when they encompass more than one conceptual lens, incorporating an educational approach along with clear disciplinary outcomes. From a policy lens (see Fig. 24.2), institutions must include both formal institutional polices as well as guiding documents, procedures, and forms (Eaton, 2021) as ethical codification is an essential resource in fostering a culture of change.

Faculty Professional Development (Teaching and Learning)

Developing a space for faculty to learn about academic integrity is one of the most critical steps. Frequently faculty at the community college level are hired for their professional expertise (trades professions, nurses, police officers) and may not have the educational background or experiences specifically related to the discipline of teaching. Professional development related to the faculty's knowledge of and role pertaining to academic policies is a vital component. This includes addressing gaps in faculty's understanding on how to handle and manage their courses, the different measures by which students can violate academic policies, including what constitutes misconduct and preventable measures (Bristor & Burke, 2016).

The role of faculty within the college classroom is to convey to students the concept and values of academic integrity and to uphold their course's integrity. This can be accomplished through classroom discussions on integrity and plagiarism, developing and maintaining the integrity of authentic assessments, and having a clear understanding of institutional (Gottardello & Karabag, 2020). This knowledge is not inherent to faculty and therefore requires a means by which faculty can obtain this understanding. Professional development and faculty support can also address the disparity that occurs between “the rhetoric of policy documents and the actual practice of integrating academic integrity in the classroom” (Gottardello & Karabag, 2020, p. 1). Taking a developmental approach in closing the praxis gap of what is ideal within best-practice and policy to implementation within the student learning environment is most effective.

Professional development may facilitate a shared understanding of integrity and the shared values inherent to the institution's socio-cultural aspects (Gottardello & Karabag, 2020). One surprising finding in our research identified that 14% of respondents felt that academic integrity among students was not important. Edification may first need to begin with faculty to impart the importance of academic integrity related to the institution's mission and vision while contributing to society's moral well-being.

Modeling Behavior

As faculty have day-to-day interactions with students, it places them in a prime position to act as role models; to collaborate, teach, engage, and inspire. Within the conceptual lens of moral perspective (Eaton et al., 2020), modeling behavior around academic integrity is one of the most valuable ways that faculty can lead by example. Faculty are leaders, experts in their fields, and professional in nature due to their role as educators. Poor role modeling can lead to misinforming students and providing bad practice occurrences, resulting in negative outcomes (Morris & Carroll, 2016). Modeling of behavior would also align with Eaton et al.'s (2020) conceptual lens of teaching and learning (see Fig. 24.2), in that faculty should ensure their own academic integrity related to course documents and resources, class activities and handouts, as well as assessments. In addition, faculty can support and encourage principles of integrity by using educational approaches to help students learn and understand these principles. Aligning with Bertram Gallant's (2008) statement that academic integrity is a crucial component to teaching and learning imperative, we believe that modeling behavior for students is one of the key outcomes of our study. Fortuitously, our research collected data related to role modeling and academic integrity within the faculty by faculty. We had more than once incident where faculty were concerned with the behavior of their colleagues and their lack of integrity. We suggest future research would be valuable related to faculty incidences of academic dishonesty.

Support

Support of and for faculty is crucial to developing a culture of integrity. In addition to exemplar academic policies, the identification of specific supports for faculty must also be included (Bretag et al., 2011; Garza Mitchell & Parnther, 2018). Supports can refer to a multitude of endeavors such as academic integrity champions (Bretag & Mahmud, 2016) who are well versed in the academic integrity discourse and can educate and support faculty. Faculty also need to feel backed by senior administration (Bristor & Burke, 2016) as faculty who do not believe they will be supported by senior administration are less likely to address and report incidents, creating further disillusionment. This includes individuals in direct supervision of faculty as well as deans, provosts, and executive leadership (Bristor & Burke, 2016). Bristor and Burke reiterate that to create and sustain a culture of integrity, all members within the community must be committed and accountable for their assigned responsibilities.

Conclusion

This chapter presented perceived barriers faced by faculty when addressing academic integrity within their institutions. Time, knowledge, support, and fear all play a significant role in determining to what extent, if at all, faculty report and address incidents of academic misconduct within the community college setting. Faculty are the front-line workers who interact with students daily and are in a prime position to positively influence students' ethical and moral integrity while upholding the intrinsic values of academic integrity, their primary institution, and post-secondary education. The faculty's role not only includes edifying students on course content and engaging students within the learning process, but faculty must also encourage fair, honest practices, and promote and model a high standard of integrity (Gottardello & Karabag, 2020). This can be achieved through initiatives that support faculty and, by extension, students, through the conceptual lenses of academic integrity including teaching and learning, policy development, and from a moral development perspective (Eaton et al., 2020). Our research identified a disjuncture between faculty's perceptions and understanding about academic misconduct and institutional expectations and policies. It is essential that academic integrity is integrated into routine discourse in all matters related to post-secondary education. This will in return create a collective understanding and community that is dedicated to upholding the fundamental principles integral to academic integrity (ICAI, 2021). These fundamental values will support students not only in achieving their educational goals but will also assist them in developing an ethical perspective, contributing to the wellbeing of society.

References

Adam, L. (2016). Student perspectives on plagiarism. In T. Bretag (Ed.), Handbook of academic integrity (pp. 519–535). Springer.

Alberta Government. (n.d.). Types of publicly funded institutions. https://www.alberta.ca/types-publicly-funded-post-secondary-institutions.aspx#jumplinks-2

Anney, V. N., & Mosha, M. A. (2015). Student's plagiarisms in higher learning institutions in the era of improved internet access: Case study of developing countries. Journal of Education and Practice, 6(13), 203–216. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1080502

Bertram Gallant, T. (2008). Academic integrity in the twenty-first century: A teaching and learning imperative. Wiley.

Bertram Gallant, T. (2016). Leveraging institutional integrity for the betterment of education. In T. Bretag (Ed.), Handbook of academic integrity (pp. 979–993). Singapore.

Bertram Gallant, T. (2018). Part-time integrity? Contingent faculty and academic integrity. New Directions for Community Colleges, 183, 45–54. https://doi.org/10.1002/cc.20316

Bertram Gallant, T., & Drinan, T. (2006). Organizational theory and student cheating: Explanation, responses, and strategies. The Journal of Higher Education, 77(5), 839–860. https://doi.org/10.1353/jhe.2006.0041

Blau, G., Szewczuk, R., Fitzgerald, J., Paris, D. A., & Guglielmo, M. (2018). Comparing business school faculty classification for perceptions of student cheating. Journal of Academic Ethics, 4(16), 301–315. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10805-018-9315-4

Bretag, T., Mahmud, S., Wallace, M., Walker, R., James, C., Green, M., East, J., McGowan, U., & Partridge, L. (2011). Core elements of exemplar academic integrity policy in Australian higher education. International Journal for Educational Integrity, 7(2), 3–12. https://ro.uow.edu.au/asdpapers/341

Bretag, T., & Harper, R. (2017). Addressing contract cheating: Local and global responses. [PowerPoint slides]. Contract Cheating and Assessment Design. https://cheatingandassessment.edu.au/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/addressing-contract-cheating_local-and-global-responses.pdf

Bretag, T., & Mahmud, S. (2016). A conceptual framework for implementing exemplary academic integrity policy in Australian higher education. In T. Bretag (Ed.), Handbook of academic integrity (pp. 463–480). Springer.

Bristor, J., & Burke, M. M. (2016). Academic integrity policies: Has your institution implemented an effective policy? The Accounting Educators' Journal, 26, 1–10. https://www.aejournal.com/ojs/index.php/aej/article/view/338

Caldwell, C. (2010). A ten-step model for academic integrity: A positive approach to business schools. Journal of Business Ethics, 92, 1–13. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007%2Fs10551-009-0144-7

Christensen Hughes, J. M., & McCabe, D. L. (2006). Academic misconduct within higher education in Canada. The Canadian Journal of Higher Education, 36(2), 1–21. http://journals.sfu.ca/cjhe/index.php/cjhe/article/view/183537/183482

Clark, A., Goodfellow, J., & Shoufani, S. (2020). Examining academic integrity using course-level learning outcomes. The Canadian Journal For The Scholarship of Teaching And Learning, 11(2). https://doi.org/10.5206/cjsotl-rcacea.2020.2.8508

Crossman, K. (2019). Is this in my contract? How part-time contract faculty face barriers to reporting academic integrity breaches. Canadian Perspectives on Academic Integrity, 2(1), 32–39. https://doi.org/10.11575/cpai.v2i1.68934

DiBartolo, M. C., & Walsh, C. M. (2010). Desperate times call for desperate measures: Where are we in addressing academic integrity? Journal of Nursing Education, 49(10), 543–544. https://doi.org/10.3928/01484834-20100921-01

Eaton, S. E., Fernandez Conde, C., Rothschuh, S., Guglielmin, M., & Kojo Otoo, B. (2020). Plagiarism: A Canadian higher education case study of policy and practice gaps. Alberta Journal of Educational Research, 66(4), 471–488. https://journalhosting.ucalgary.ca/index.php/ajer/article/view/69204

Eaton, S. E. (2021). Plagiarism in higher education: Tackling tough topics in academic integrity. Libraries Unlimited.

Fontana, J. S. (2009). Nursing faculty experiences of students’ academic misconduct. Journal of Nursing Education, 48(4), 181–185. https://doi.org/10.3928/01484834-20090401-05

Garza Mitchell, R. L., & Parnther, C. (2018). The shared responsibility for academic integrity education. New Directions for Community Colleges, 183, 55–64. https://doi.org/10.1002/cc.20317

Gottardello, D., & Karabag, S. F. (2020). Ideal and actual roles of university professors in academic integrity management: A comparative study. Studies in Higher Education. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2020.1767051

Hendricks, E., Young-Jones, A., & Foutch, J. (2011). To cheat or not to cheat: Academic misconduct in the college classroom. LOGOS: A Journal of Undergraduate Research, 4, 68–75. https://www.missouristate.edu/Assets/honorslogos/logos_vol4_full.pdf#page=76

International Center for Academic Integrity (ICAI). (2021). The fundamental values of academic integrity (3rd ed.). https://www.academicintegrity.org/fundamental-values/

Keener, T. A., Peralya, M. G., Smith, M., Swager, L., Ingles, J., Wen, S., & Barbier, M. (2019). Student and faculty perceptions: Appropriate consequences of lapses in academic integrity in health sciences education. BMC Medical Education, 19(209), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-019-1645-4

Keith-Spiegel, P., Tabachnick, B. G., Whitley Jr, B. E., & Washburn, J. (1998). Why professors ignore cheating: Opinions of a national sample of psychology instructors. Ethics and Behavior, 8(3), 215-227.https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327019eb0803_3

Keith-Spiegel, P., Tabachnick, B. G., Whitley Jr., B. E., & Washburn, J. (2010). Why professors ignore cheating: Opinions of a national sample of psychology faculty. Ethics and Behavior, 8(3), 215–227. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327019eb0803_3

Kenny, N., & Eaton, S. E. (2022). Academic integrity through a SoTL lens and 4M framework: An institutional self-study. In S. E. Eaton & J. Christensen Hughes (Eds.), Academic integrity in Canada: An enduring and essential challenge. Springer.

Madara, D. S., & Namango, S. (2016). Faculty perceptions on cheating in exams in undergraduate engineering. Journal of Education and Practice, 7(30), 70–86. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1118895.pdf

McCabe, D. L. (1993). Faculty responses to academic misconduct: The influence of student honor codes. Research in Higher Education, 34(5), 647–658. https://www.jstor.org/stable/40196116

McCabe, D. L., Butterfield, K., & Treviño, L. K. (2012). Cheating in college: Why students do it and what educators can do about it. John Hopkins University Press.

Morris, E. J., & Carroll, J. (2016). Developing a sustainable holistic institutional approach: Dealing with realities ‘on the ground’ when implementing an academic integrity policy. In T. Bretag (Ed.), Handbook of academic integrity (pp. 449–462). Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-287-098-8_23

Morris, E. J. (2018). Academic integrity matters: Five considerations for addressing contract cheating. International Journal for Educational Integrity, 14(15). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40979-018-0038-5

Orr, J. (2018). Developing a campus academic integrity education seminar. Journal of Academic Ethics, 16(3), 195–209. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10805-018-9304-7

Parnther, C. (2016). It's on us: A case study of academic integrity in a Mid-Western community college (Publication No. 2468) (Doctoral dissertation, Western Michigan University, 2016). Scholarworks. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=3490&context=dissertations

Schneider, A. (1999). Why professors don't do more to stop students who cheat. The Chronicle of Higher Education, 45(20), 8–13. https://www.chronicle.com/article/why-professors-dont-do-more-to-stop-students-who-cheat-25673/

Shane, M. J., Carson, L., & Edwards, M. (2018). A case study in updating academic policies and procedures. New Directions for Community Colleges, 2018(183), 83–93. https://doi.org/10.1002/cc.20320

Stoesz, B. M., & Eaton, S. E. (2020). Academic integrity policies of publicly funded universities in western Canada. Educational Policy. https://doi.org/10.1177/0895904820983032

Stoesz, B. M., Eaton, S. E., Miron, J., & Thacker, E. J. (2019). Academic integrity and contract cheating policy analysis of colleges in Ontario, Canada. International Journal for Educational Integrity, 15(4), 2–18. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40979-019-0042-4

Tayan, B. M. (2017). Academic misconduct: An investigation into male students’ perceptions, experiences & attitudes towards cheating and plagiarism in a Middle Eastern university context. Journal of Education and Learning, 6(1), 158–166. https://doi.org/10.5539/jel.v6n1p158

Thomas, A. (2017). Faculty reluctance to report student plagiarism. A case study. African Journal of Business Ethics, 11(1), 103–119. https://doi.org/10.15249/11-1-148

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2022 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Hamilton, M., Wolsky, K. (2022). The Barriers to Faculty Reporting Incidences of Academic Misconduct at Community Colleges. In: Eaton, S.E., Christensen Hughes, J. (eds) Academic Integrity in Canada. Ethics and Integrity in Educational Contexts, vol 1. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-83255-1_24

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-83255-1_24

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-83254-4

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-83255-1

eBook Packages: EducationEducation (R0)