Abstract

This chapter addresses why there is a need for experts and lay people to think critically about medicine and health. It will be argued that illogical, misleading, and contradictory information in medicine and health can have pernicious consequences, including patient harm and poor compliance with health recommendations. Our cognitive resources are our only bulwark to the misinformation and faulty logic that exists in medicine and health. One resource in particular—reasoning—can counter the flawed thinking that pervades many medical and health issues. This chapter examines how concepts such as reasoning, logic and argument must be conceptualised somewhat differently (namely, in non-deductive terms) to accommodate the rationality of the informal fallacies. It also addresses the relevance of the informal fallacies to medicine and health and considers how these apparently defective arguments are a source of new analytical possibilities in both domains.

Access this chapter

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

References

Albano, J. D., Ward, E., Jemal, A., Anderson, R., Cokkinides, V. E., Murray, T., et al. (2007). Cancer mortality in the United States by education level and race. Journal of the National Cancer Institute, 99(18), 1384–1394.

Coxon, J., & Rees, J. (2015). Avoiding medical errors in general practice. Trends in Urology & Men’s Health, 6(4), 13–17.

Croskerry, P. (2003). The importance of cognitive errors in diagnosis and strategies to minimize them. Academic Medicine, 78(8), 775–780.

Cummings, L. (2002). Reasoning under uncertainty: The role of two informal fallacies in an emerging scientific inquiry. Informal Logic, 22(2), 113–136.

Cummings, L. (2004). Analogical reasoning as a tool of epidemiological investigation. Argumentation, 18(4), 427–444.

Cummings, L. (2009). Emerging infectious diseases: Coping with uncertainty. Argumentation, 23(2), 171–188.

Cummings, L. (2010). Rethinking the BSE crisis: A study of scientific reasoning under uncertainty. Dordrecht: Springer.

Cummings, L. (2011). Considering risk assessment up close: The case of bovine spongiform encephalopathy. Health, Risk & Society, 13(3), 255–275.

Cummings, L. (2012a). Scaring the public: Fear appeal arguments in public health reasoning. Informal Logic, 32(1), 25–50.

Cummings, L. (2012b). The public health scientist as informal logician. International Journal of Public Health, 57(3), 649–650.

Cummings, L. (2013a). Public health reasoning: Much more than deduction. Archives of Public Health, 71(1), 25.

Cummings, L. (2013b). Circular reasoning in public health. Cogency, 5(2), 35–76.

Cummings, L. (2014a). Informal fallacies as cognitive heuristics in public health reasoning. Informal Logic, 34(1), 1–37.

Cummings, L. (2014b). The ‘trust’ heuristic: Arguments from authority in public health. Health Communication, 29(10), 1043–1056.

Cummings, L. (2014c). Coping with uncertainty in public health: The use of heuristics. Public Health, 128(4), 391–394.

Cummings, L. (2014d). Circles and analogies in public health reasoning. Inquiry, 29(2), 35–59.

Cummings, L. (2014e). Analogical reasoning in public health. Journal of Argumentation in Context, 3(2), 169–197.

Cummings, L. (2015). Reasoning and public health: New ways of coping with uncertainty. Cham, Switzerland: Springer.

Fowler, F. J., Jr., Levin, C. A., & Sepucha, K. R. (2011). Informing and involving patients to improve the quality of medical decisions. Health Affairs, 30(4), 699–706.

Graber, M. L., Franklin, N., & Gordon, R. (2005). Diagnostic error in internal medicine. Archives of Internal Medicine, 165(13), 1493–1499.

Hamblin, C. L. (1970). Fallacies. London: Methuen.

Johnson, R. H. (2011). Informal logic and deductivism. Studies in Logic, 4(1), 17–37.

Kahane, H. (1971). Logic and contemporary rhetoric: The use of reason in everyday life. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth Publishing Company.

Loucks, E. B., Buka, S. L., Rogers, M. L., Liu, T., Kawachi, I., Kubzansky, L. D., et al. (2012). Education and coronary heart disease risk associations may be affected by early life common prior causes: A propensity matching analysis. Annals of Epidemiology, 22(4), 221–232.

Saposnik, G., Redelmeier, D., Ruff, C. C., & Tobler, P. N. (2016). Cognitive biases associated with medical decisions: A systematic review. BMC Medical Informatics and Decision Making, 16, 138. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12911-016-0377-1.

Trowbridge, R. L. (2008). Twelve tips for teaching avoidance of diagnostic errors. Medical Teacher, 30, 496–500.

Walton, D. N. (1985a). Are circular arguments necessarily vicious? American Philosophical Quarterly, 22(4), 263–274.

Walton, D. N. (1985b). Arguer’s Position. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press.

Walton, D. N. (1987). The ad hominem argument as an informal fallacy. Argumentation, 1(3), 317–331.

Walton, D. N. (1991). Begging the question: Circular reasoning as a tactic of argumentation. New York: Greenwood Press.

Walton, D. N. (1992). Plausible argument in everyday conversation. Albany: SUNY Press.

Walton, D. N. (1996). Argumentation schemes for presumptive reasoning. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Walton, D. N. (2010). Why fallacies appear to be better arguments than they are. Informal Logic, 30(2), 159–184.

Weingart, S. N., Wilson, R. M., Gibberd, R. W., & Harrison, B. (2000). Epidemiology of medical error. Western Journal of Medicine, 172(6), 390–393.

Woods, J. (1995). Appeal to force. In H. V. Hansen & R. C. Pinto (Eds.), Fallacies: Classical and contemporary readings (pp. 240–250). University Park: The Pennsylvania State University Press.

Woods, J. (2004). The death of argument: Fallacies in agent-based reasoning. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic.

Woods, J. (2007). Lightening up on the ad hominem. Informal Logic, 27(1), 109–134.

Woods, J. (2008). Begging the question is not a fallacy. In C. Dégremont, L. Keiff, & H. Rükert (Eds.), Dialogues, logics and other strange things: Essays in honour of Shahid Rahman (pp. 523–544). London: College Publications.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Chapter Summary

Key points

-

Medicine and health have tended to be overlooked in the critical thinking literature . And yet robust critical thinking skills are needed to evaluate the large number and range of health messages that we are exposed to on a daily basis.

-

An ability to think critically helps us to make better personal health choices and to uncover biases and errors in health messages and other information. An ability to think critically allows us to make informed decisions about medical treatments and is vital to efforts to reduce medical diagnostic errors.

-

A key element in critical thinking is the ability to distinguish strong or valid reasoning from weak or invalid reasoning. When an argument is weak or invalid, it is called a ‘fallacy’ or a ‘fallacious argument’.

-

The informal fallacies are so-called on account of the presence of epistemic and dialectical flaws that cannot be captured by formal logic . They have been discussed by many generations of philosophers and logicians , beginning with Aristotle .

-

Historically, philosophers and logicians have taken a pejorative view of the informal fallacies. Much of the criticism of these arguments is related to a latent deductivism in logic , the notion that arguments should be evaluated according to deductive standards of validity and soundness . Against deductive standards and norms, many reasonable arguments are judged to be fallacies.

-

Developments in logic , particularly the teaching of logic, forced a reconsideration of the prominence afforded to deductive logic in the evaluation of arguments. New criteria based on presumptive reasoning and plausible argument started to emerge. Against this backdrop, non-fallacious variants of most of the informal fallacies began to be described for the first time.

-

Today, some argument analysts characterize non-fallacious variants of the informal fallacies in terms of cognitive heuristics . During reasoning , these heuristics function as mental shortcuts, allowing us to bypass knowledge and come to judgement about complex health problems.

Suggestions for Further Reading

-

(1)

Sharples, J. M., Oxman, A. D., Mahtani, K. R., Chalmers, I., Oliver, S., Collins, K., Austvoll-Dahlgren, A., & Hoffmann, T. (2017). Critical thinking in healthcare and education. British Medical Journal, 357: j2234. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.j2234.

The authors examine the role of critical thinking in medicine and healthcare, arguing that critical thinking skills are essential for doctors and patients. They describe an international project that involves collaboration between education and health. Its aim is to develop a curriculum and learning resources for critical thinking about any action that is claimed to improve health.

-

(2)

Hitchcock, D. (2017). On reasoning and argument: Essays in informal logic and on critical thinking. Cham: Switzerland: Springer.

This collection of essays provides more advanced reading on several of the topics addressed in this chapter, including the fallacies, informal logic , and the teaching of critical thinking . Chapter 25 considers if fallacies have a place in the teaching of critical thinking and reasoning skills.

-

(3)

Hansen, H. V., & Pinto, R. C. (Eds.). (1995). Fallacies: Classical and contemporary readings. University Park: The Pennsylvania State University Press.

This edited collection of 24 chapters contains historical selections on the fallacies, contemporary theory and criticism, and analyses of specific fallacies. It also examines fallacies and teaching. There are chapters on four of the fallacies that will be examined in this book: appeal to force; appeal to ignorance ; appeal to authority; and post hoc ergo propter hoc .

Questions

-

(1)

Diagnostic errors are a significant cause of death and serious injury in patients. Many of these errors are related to cognitive factors. Trowbridge (2008) has devised twelve tips to familiarize medical students and physician trainees with the cognitive underpinnings of diagnostic errors. One of these tips is to explicitly describe heuristics and how they affect clinical reasoning . These heuristics include the following:

-

Representativeness—a patient’s presentation is compared to a ‘typical’ case of specific diagnoses.

-

Availability —physicians arrive at a diagnosis based on what is easily accessible in their minds, rather than what is actually most probable.

-

Anchoring—physicians may settle on a diagnosis early in the diagnostic process and subsequently become ‘anchored’ in that diagnosis.

-

Confirmation bias—as a result of anchoring, physicians may discount information discordant with the original diagnosis and accept only that which supports the diagnosis.

-

Using the above information, identify any heuristics and biases that occur in the following scenarios:

Scenario 1: A 60-year-old man has epigastric pain and nausea. He is sitting forward clutching his abdomen. He has a history of several bouts of alcoholic pancreatitis. He states that he felt similar during these bouts to what he is currently feeling. The patient states that he has had no alcohol in many years. He has normal blood levels of pancreatic enzymes. He is given a diagnosis of acute pancreatitis. It is eventually discovered that he has had acute myocardial infarction.

Scenario 2: A 20-year-old, healthy man presents with sudden onset of severe, sharp chest pain and back pain. Based on these symptoms, he is suspected of having a dissecting thoracic aortic aneurysm. (In an aortic dissection, there is a separation of the layers within the wall of the aorta, the large blood vessel branching off the heart.) He is eventually diagnosed with pleuritis (inflammation of the pleura, the thin, transparent, two-layered membrane that covers the lungs).

-

(2)

Many of the logical terms that were introduced in this chapter also have non-logical uses in everyday language. Below are several examples of the use of these terms. For each example, indicate if the word in italics has a logical or a non-logical meaning or use:

-

(a)

University ‘safe spaces’ are a dangerous fallacy—they do not exist in the real world (The Telegraph, 13 February 2017).

-

(b)

The MRI findings beg the question as to whether a careful ultrasound examination might have yielded some of the same information on haemorrhages (British Medical Journal: Fetal & Neonatal, 2011).

-

(c)

The youth justice system is a slippery slope of failure (The Sydney Morning Herald, 26 July 2016).

-

(d)

The EU countered with its own gastronomic analogy , saying that “cherry picking” the best bits of the EU would not be tolerated (BBC News, 28 July 2017).

-

(e)

As Ebola spreads, so have several fallacies (The New York Times, 23 October 2014).

-

(f)

Removing the statue of Confederacy Army General Robert E. Lee no more puts us on a slippery slope towards ousting far more nuanced figures from the public square than building the statue in the first place put us on a slippery slope toward, say, putting up statues of Hitler outside of Holocaust museums or of Ho Chi Minh at Vietnam War memorials (Chicago Tribune, 16 August 2017).

-

(g)

We can expand the analogy a bit and think of a culture as something akin to a society’s immune system—it works best when it is exposed to as many foreign bodies as possible (New Zealand Herald, 4 May 2010).

-

(h)

The Josh Norman Bowl begs the question: What’s an elite cornerback worth? (The Washington Post, 17 December 2016).

-

(i)

The intuition behind these analogies is simple: As a homeowner, I generally have the right to exclude whoever I want from my property. I don’t even have to have a good justification for the exclusion. I can choose to bar you from my home for virtually any reason I want, or even just no reason at all. Similarly, a nation has the right to bar foreigners from its land for almost any reason it wants, or perhaps even no reason at all (The Washington Post, 6 August 2017).

-

(j)

Legalising assisted suicide is a slippery slope toward widespread killing of the sick, Members of Parliament and peers were told yesterday (Mail Online, 9 July 2014).

-

(a)

-

(3)

In the Special Topic ‘What’s in a name?’, an example of a question-begging argument from the author’s recent personal experience was used. How would you reconstruct the argument in this case to illustrate the presence of a fallacy?

-

(4)

On 9 July 2017, the effect of coconut oil on health was also discussed in an article in The Guardian entitled ‘Coconut oil: Are the health benefits a big fat lie?’ The following extract is taken from that article. (a) What type of reasoning is the author using in this extract? In your response, you should reconstruct the argument by presenting its premises and conclusion . Also, is this argument valid or fallacious in this particular context?

When it comes to superfoods, coconut oil presses all the buttons: it’s natural, it’s enticingly exotic, it’s surrounded by health claims and at up to £8 for a 500 ml pot at Tesco, it’s suitably pricey. But where this latest superfood differs from benign rivals such as blueberries, goji berries, kale and avocado is that a diet rich in coconut oil may actually be bad for us.

The article in The Guardian also makes extensive use of expert opinion. Two such opinions are shown below. (b) What three linguistic devices does the author use to confer expertise or authority on the individuals who advance these opinions?

Christine Williams, professor of human nutrition at the University of Reading, states: “There is very limited evidence of beneficial health effects of this oil”.

Tom Sanders, emeritus professor of nutrition and dietetics at King’s College London, says: “It is a poor source of vitamin E compared with other vegetable oils”.

The author of the article in The Guardian went on to summarize the findings of a study by two researchers that was published in the British Nutrition Foundation’s Nutrition Bulletin. The author’s summary included the following statement: There is no good evidence that coconut oil helps boost mental performance or prevent Alzheimer’s disease . (c) In what type of informal fallacy might this statement be a premise ?

Answers

(1)

Scenario 1: An anchoring error has occurred in which the patient is given a diagnosis of acute pancreatitis early in the diagnostic process. The clinician becomes anchored in this diagnosis, with the result that he overlooks two pieces of information that would have allowed this diagnosis to be disconfirmed—the fact that the patient has reported no alcohol use in many years and the presence of normal blood levels of pancreatic enzymes. By dismissing this information, the clinician is also showing a confirmation bias —he attends only to information that confirms his original diagnosis.

Scenario 2: A representativeness error has occurred. The patient’s presentation is typical of aortic dissection. However, this condition can be dismissed in favour of conditions like pleuritis or pneumothorax on account of the fact that aortic dissection is exceptionally rare in 20-year-olds.

(2) (a) non-logical; (b) non-logical; (c) non-logical; (d) non-logical; (e) non-logical; (f) logical; (g) logical; (h) non-logical; (i) logical; (j) logical

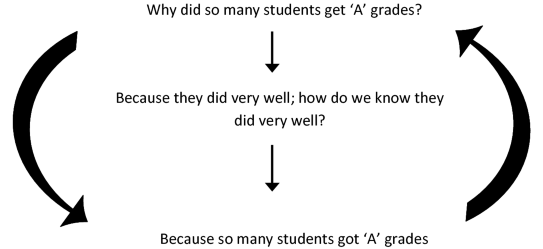

(3) The fallacy can be illustrated as follows. The head of department asks the question ‘Why did so many of these students get ‘A’ grades’? He receives the reply ‘Because they did very well’. But someone might reasonably ask ‘How do we know that they did very well?’ To which the reply is ‘Because so many students got ‘A’ grades’. The reasoning can be reconstructed in diagram form as follows:

(4)

-

(a)

The author is using an analogical argument , which has the following form:

P1: Blueberries, goji berries, kale, avocado and coconut oil are natural, exotic, pricey and surrounded by health claims.

P2: Blueberries, goji berries, kale and avocado have health benefits.

C: Coconut oil has health benefits.

This is a false analogy , or a fallacious analogical argument , because coconut oil does not share with these other superfoods the property or attribute <has health benefits>.

-

(b)

The author uses academic rank, field of specialization, and university affiliation to confer authority or expertise on individuals who advance expert opinions.

-

(c)

This statement could be a premise in an argument from ignorance .

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2020 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Cummings, L. (2020). Critical Thinking in Medicine and Health. In: Fallacies in Medicine and Health. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-28513-5_1

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-28513-5_1

Published:

Publisher Name: Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-28512-8

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-28513-5

eBook Packages: Social SciencesSocial Sciences (R0)