Abstract

Background

Several studies have shown that treatment with HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors (statins) can reduce coronary heart disease (CHD) rates. However, the cost effectiveness of statin treatment in the primary prevention of CHD has not been fully established.

Objective

To estimate the costs of CHD prevention using statins in Switzerland according to different guidelines, over a 10-year period.

Methods

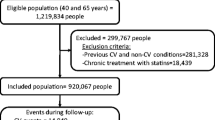

The overall 10-year costs, costs of one CHD death averted, and of 1 year without CHD were computed for the European Society of Cardiology (ESC), the International Atherosclerosis Society (IAS), and the US Adult Treatment Panel III (ATP-III) guidelines. Sensitivity analysis was performed by varying number of CHD events prevented and costs of treatment.

Results

Using an inflation rate of medical costs of 3%, a single yearly consultation, a single total cholesterol measurement per year, and a generic statin, the overall 10-year costs of the ESC, IAS, and ATP-III strategies were 2.2, 3.4, and 4.1 billion Swiss francs (SwF [SwF1 = $US0.97]). In this scenario, the average cost for 1 year of life gained was SwF352, SwF421, and SwF485 thousand, respectively, and it was always higher in women than in men. In men, the average cost for 1 year of life without CHD was SwF30.7, SwF42.5, and SwF51.9 thousand for the ESC, IAS, and ATP-III strategies, respectively, and decreased with age. Statin drug costs represented between 45% and 68% of the overall preventive cost. Changing the cost of statins, inflation rates, or number of fatal and non-fatal cases of CHD averted showed ESC guidelines to be the most cost effective. Conclusion: The cost of CHD prevention using statins depends on the guidelines used. The ESC guidelines appear to yield the lowest costs per year of life gained free of CHD.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Leal J, Luengo-Fernández R, Gray A, et al. Economic burden of cardiovascular diseases in the enlarged European Union. Eur Heart J 2006; 27(13): 1610–9.

Swiss Health Observatory. Health in Switzerland. National Health Report 2008-summary. Neuchâtel: Federal Statistical Office (FSO), 2008.

Federal Office of Statistics. Décès: nombre, évolution et causes. Neuchâtel: Federal Statistical Office (FSO), 2009 Apr 6.

Wietlisbach V. Commission d’information de la Fondation Suisse de Cardiologie. Chiffres et données sur les maladies cardio-vasculaires en Suisse [in French]. Bern: Swiss Heart Foundation, 2004.

Thavendiranathan P, Bagai A, Brookhart MA, et al. Primary prevention of cardiovascular diseases with statin therapy: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Arch Intern Med 2006; 166(21): 2307–13.

Morrison A, Glassberg H. Determinants of the cost-effectiveness of statins. J Manag Care Pharm 2003; 9(6): 544–51.

Szucs TD. Pharmaco-economic aspects of lipid-lowering therapy: is it worth the price? Eur Heart J 1998; 19 Suppl. M: M22–8.

Ward S, Lloyd Jones M, Pandor A, et al. A systematic review and economic evaluation of statins for the prevention of coronary events. Health Technol Assess 2007; 11(14): 1–160.

Franco OH, der Kinderen AJ, De Laet C, et al. Primary prevention of cardiovascular disease: cost-effectiveness comparison? Int J Technol Assess Health Care 2007; 23(1): 71–9.

Franco OH, Peeters A, Looman CW, et al. Cost effectiveness of statins in coronary heart disease. J Epidemiol Comm Health 2005; 59(11): 927–33.

Nanchen D, Chiolero A, Cornuz J, et al. Cardiovascular risk estimation and eligibility for statins in primary prevention comparing different strategies. Am J Cardiol 2009; 103(8): 1089–95.

Firmann M, Mayor V, Vidal PM, et al. The CoLaus study: a population-based study to investigate the epidemiology and genetic determinants of cardiovascular risk factors and metabolic syndrome. BMC Cardiovasc Disord 2008; 8: 6. Epub.

Assmann G, Cullen P, Schulte H. Simple scoring scheme for calculating the risk of acute coronary events based on the 10-year follow-up of the prospective cardiovascular Munster (PROCAM) study. Circulation 2002; 105(3): 310–5.

Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults. Executive Summary of the third report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III). JAMA 2001; 285(19): 2486–97.

Conroy RM, Pyörälä K, Fitzgerald AP, et al. Estimation of ten-year risk of fatal cardiovascular disease in Europe: the SCORE project. Eur Heart J 2003; 24(11): 987–1003.

Graham I, Atar D, Borch-Johnsen K, et al. European guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice: executive summary. Fourth Joint Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology and Other Societies on Cardiovascular Disease Prevention in Clinical Practice. Eur Heart J 2007; 28(19): 2375–414.

International Atherosclerosis Society. Harmonized guidelines on prevention of atherosclerotic cardiovascular diseases: full report, 30 April 2003 [online]. Available from URL: www.athero.org.cn/gdline/fullreport.pdf [Accessed 2009 Apr 1].

Rodondi N, Cornuz J, Marques-Vidal P, et al. Aspirin use for the primary prevention of coronary heart disease: a population-based study in Switzerland. Prev Med 2008; 46(2): 137–44.

Manuel DG, Kwong K, Tanuseputro P, et al. Effectiveness and efficiency of different guidelines on statin treatment for preventing deaths from coronary heart disease: modelling study. BMJ 2006; 332(7555): 1419–24.

Fox CS, Evans JC, Larson MG, et al. Temporal trends in coronary heart disease mortality and sudden cardiac death from 1950 to 1999: the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation 2004; 110(5): 522–7.

Rickenbach M, Wietlisbach V, Barazzoni F, et al. Hospitalisation pour infarctus du myocarde dans les cantons de Vaud, Fribourg et Tessin: résultats de l’étude MONICA pour la période 1985–1988. Médecine et Hygiène 1992; 50: 350–4.

Tunstall-Pedoe H, Kuulasmaa K, Mahonen M, et al. Contribution of trends in survival and coronary-event rates to changes in coronary heart disease mortality: 10-year results from 37 WHO MONICA project populations. Monitoring trends and determinants in cardiovascular disease? Lancet 1999; 353(9164): 1547–57.

Arzneimittel-Kompendium der Schweiz [online]. Available from URL: http:// www.kompendium.ch/NutzungsbedingungenAkzeptieren [Accessed 2010 Nov 1].

Bramkamp M, Radovanovic D, Erne P, et al. Determinants of costs and the length of stay in acute coronary syndromes: a real life analysis of more than 10,000 patients. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther 2007; 21(5): 389–98.

Levy E, Gabriel S, Dinet J. The comparative medical costs of atherothrombotic disease in European countries. Pharmacoeconomics 2003; 21(9): 651–9.

Jeanloz T. Evolution des salaires 2007 [in French]. Neuchâtel: Office fédéral de la statistique (OFS), 2008.

Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). OECD reviews of health systems Switzerland. Paris: Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), 2006.

Abbas AE, Brodie B, Stone G, et al. Frequency of returning to work one and six months following percutaneous coronary intervention for acute myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol 2004; 94(11): 1403–5.

Brink E, Brändström Y, Cliffordsson C, et al. Illness consequences after myocardial infarction: problems with physical functioning and return to work. J Adv Nurs 2008; 64(6): 587–94.

Salomaa V, Ketonen M, Koukkunen H, et al. Decline in out-of-hospital coronary heart disease deaths has contributed the main part to the overall decline in coronary heart disease mortality rates among persons 35 to 64 years of age in Finland: the FINAMI study. Circulation 2003; 108(6): 691–6.

Statistique Suisse [online]. Available from URL: http://www.bfs.admin.ch/bfs/ portal/fr/index/themen/03/04/ [Accessed 2010 Nov 1].

Salomaa V, Ketonen M, Koukkunen H, et al. Trends in coronary events in Finland during 1983–1997: the FINAMI study. Eur Heart J 2003; 24(4): 311–9.

Lee H, Manns B, Taub K, et al. Cost analysis of ongoing care of patients with end-stage renal disease: the impact of dialysis modality and dialysis access. Am J Kidney Dis 2002; 40(3): 611–22.

Martin PY, Burnier M. La dialyse oui, mais a quel prix [in French]? Rev Med Suisse 2005; 1(8): 531–2.

Pletcher MJ, Lazar L, Bibbins-Domingo K, et al. Comparing impact and cost-effectiveness of primary prevention strategies for lipid-lowering. Ann Intern Med 2009; 150(4): 243–54.

Rockson SG. Benefits of lipid-lowering agents in stroke and coronary heart disease: pharmacoeconomics. Curr Atheroscler Rep 2000; 2(2): 144–50.

Franco OH, Steyerberg EW, Peeters A, et al. Effectiveness calculation in economic analysis: the case of statins for cardiovascular disease prevention. J Epidemiol Comm Health 2006; 60(10): 839–45.

Müller-Nordhorn J, Binting S, Roll S, et al. An update in regional variation in cardiovascular mortality within Europe. Eur Heart J 2008; 29(10): 1316–26.

Marques-Vidal P, Rodondi N, Bochud M, et al. Predictive accuracy of original and recalibrated Framingham risk score in the Swiss population. Int J Cardiol 2009; 133(3): 346–53.

Marrugat J, D’Agostino R, Sullivan L, et al. An adaptation of the Framingham coronary heart disease risk function to European Mediterranean areas. J Epidemiol Comm Health 2003; 57(8): 634–8.

Grover SA, Ho V, Lavoie F, et al. The importance of indirect costs in primary cardiovascular disease prevention: can we save lives and money with statins? Arch Intern Med 2003; 163(3): 333–9.

Hayward RA, Krumholz HM, Zulman DM, et al. Optimizing statin treatment for primary prevention of coronary artery disease. Ann Intern Med 2010; 152(2): 69–77.

McElduff P, Jaefarnezhad M, Durrington PN. American, British and European recommendations for statins in the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease applied to British men studied prospectively. Heart 2006; 92(9): 1213–8.

Conway AM, Musleh G. Which is the best statin for the postoperative coronary artery bypass graft patient? Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2009; 36(4): 628–32.

Tran YB, Frial T, Miller PS. Statin’s cost-effectiveness: a Canadian analysis of commonly prescribed generic and brand name statins. Can J Clin Pharmacol 2007; 14(2):e205–14.

Acknowledgments

The CoLaus study was supported by research grants from Glaxo-SmithKline, the Faculty of Biology and Medicine of Lausanne, Switzerland and the Fonds National Suisse de la Recherche (grant no: 33CSCO-122661). Dr Rodondi has received unrestricted grant funding from Pfizer for an investigator-initiated study to assess quality of care in Switzerland and speaker fees from Pfizer, AstraZeneca, and MSD. None of the other authors have any additional conflicts of interest to declare that relate to the content of this article. The authors express their gratitude to the participants in the Lausanne CoLaus study; to the investigators who have contributed to the recruitment of patients, and in particular Yolande Barreau, Anne-Lise Bastian, Binasa Ramic, Martine Moranville, Martine Baumer, Marcy Sagette, Jeanne Ecoffey, and Sylvie Mermoud for data collection. We thank Vincent Mooser from GlaxoSmithKline and Christophe Pinget for assistance in writing the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix 1

Appendix 1

Formulas used

10-year cost of prevention for one subject

Pr ev = (A × 365.25 + B + C) × 10 × (1 + D)9

A = daily cost of statins (see Methods for further details)

B = yearly cost of biological assessments (see Methods for further details)

C = yearly cost of medical consultations (see Methods for further details)

D = yearly inflation of medical costs (set here at 3%).[27]

Overall cost of prevention for sex x

Nix = number of subjects eligible and untreated in the Swiss population without cardiovascular disease for age group i and sex x (obtained from Nanchen et al.[11]).

It is assumed that the number of subjects who cease to take statins due to death or other reasons is negligible relative to SNix.

Cost to prevent one death from coronary heart disease for sex x

Deathix = number of potential CHD deaths averted by statins in the Swiss population if there is full compliance with guidelines for age group i and sex x (obtained from Nanchen et al.[11]).

Five-year cost of a non-fatal myocardial infarction (MI) for sex x

5NF x − (E + F + G × (K − 1)) × (1 + D)4 + (12 × J × K) × H x

D = yearly inflation of medical costs (set here at 3%)[27]

E = cost of acute treatment of an MI[24]

F = first year (non-acute) cost of treating a patient with an MI[25]

G = subsequent yearly cost of treating a patient with an MI[25]

Hx = median monthly salary for sex x (set here at SwF6000 for men and SwF5000 for women)[26]

J = % work loss (set here at 20%)[28,29]

K = number of years (set here at the median of the 10-year period, i.e. 5).

The first part of the equation relates to medical expenses while the other part relates to productivity losses.

Five-year cost of a fatal MI for sex x

5F x = (E × L x) + (12 × K) × H x × (1 + M)K −1

E = cost of acute treatment of an MI[24]

K = number of years (set here at the median of the 10-year period, i.e. 5)

Lx = percentage of fatal myocardial infarctions of sex x who are hospitalized (set here at 27% for men and 40% for women)[32]

Hx = median monthly salary for sex x (set here at SwF6000 for men and SwF5000 for women)[26]

M = average yearly increase in salaries (set here at 2%).

The first part of the equation relates to medical expenses while the other part relates to productivity losses.

Average cost of year of life gained for a 5-year period for sex x (as in table III)

Deathix = number of potential CHD deaths averted by statins in the Swiss population if there is full compliance with guidelines for age group i and sex x (obtained from Nanchen et al.[11]).

Average cost of year of life without CHD for a 5-year period for sex x (as in table IV)

CHDix = potential MI averted if statin for all eligible adults of age i and sex x (obtained from Nanchen et al.[11]).

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ito, M., Nanchen, D., Rodondi, N. et al. Statins for Cardiovascular Prevention According to Different Strategies. Am J Cardiovasc Drugs 11, 33–44 (2011). https://doi.org/10.2165/11586760-000000000-00000

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.2165/11586760-000000000-00000