Abstract

Background and objectives

More and more anticancer chemotherapies are now available as oral formulations. This relatively new route of administration in oncology leads to problems with patient education and non-compliance. The aim of this study was to explore the performances of the ‘inverse problem’, namely, estimation of compliance from pharmacokinetics. For this purpose, we developed and evaluated a method to estimate patient compliance with an oral chemotherapy in silico (i) from an a priori population pharmacokinetic model; (ii) with limited optimal pharmacokinetic information collected on day 1; and (iii) from a single pharmacokinetic sample collected after multiple doses.

Methods

Population pharmacokinetic models, including estimation of all fixed and random effects estimated on a prior dataset, and sparse samples taken after the first dose, were combined to provide the individual POSTHOC Bayesian pharmacokinetic parameter estimates. Sampling times on day 1 were chosen according to a D-optimal design. Individual pharmacokinetic profiles were simulated according to various dose-taking scenarios.

To characterize compliance over the n previous dosing times (supposedly known without error), 2n different compliance scenarios of doses taken/not taken were considered. The observed concentration value was compared with concentrations predicted from the model and each compliance scenario. To discriminate between different compliance profiles, we used the Euclidean distance between the observed pharmacokinetic values and the predicted values simulated without residual errors.

This approach was evaluated in silico and applied to imatinib and capecitabine, the pharmacokinetics of which are described in the literature, and which have quite different pharmacokinetic characteristics (imatinib has an elimination half-life of 17 hours, and α-fluoro-β-alanine [FBAL], the metabolite of capecitabine, has an elimination half-life of 3 hours). 1000 parameter sets were drawn according to population distributions, and concentration values were simulated at several timepoints under various compliance patterns to compare with the predicted ones. In addition, several simulation scenarios were run in order to explore the impact of the quality of the error model, interoccasion variability (IOV), error in the number of pills taken, and the performance of the compliance estimation method.

Results

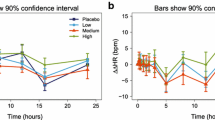

The best compliance estimate was obtained with pharmacokinetic samples taken 5 hours after the last dose. Performance of the method varied between simulation scenarios. In both the imatinib and capecitabine basic simulations, patient compliance was correctly estimated on the two last scheduled doses (with better results for imatinib). The magnitude of the error model also had a great impact on the quality of the compliance estimate.

Conclusions

We highlight the effect of three parameters on the quality of compliance estimates based on limited pharmacokinetic information: the plasma elimination half-life, interdose interval and magnitude of the error model. Nevertheless, the pharmacokinetic method is not informative enough and should be used with electronic monitoring, which provides additional information on compliance. Our method will be used in a future phase IV clinical trial where the relationships between compliance, efficacy and tolerability will be assessed.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Liu G, Franssen E, Fitch MI, et al. Patient preferences for oral versus intravenous palliative chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol 1997 Jan; 15(1): 110–5

Chau I, Legge S, Fumoleau P. The vital role of education and information in patients receiving capecitabine (Xeloda®). Eur J Oncol Nurs 2004; 8(3 Suppl.): S41–53

Gerbrecht BM, Kangas T. Implications of capecitabine (Xeloda®) for cancer nursing practice. Eur J Oncol Nurs 2004; 8(3 Suppl.): S63–71

Grober SE, Carpenter RC, Glassman M, et al. A comparison of patients’ perceptions of oral cancer treatments and intravenous cancer treatments: what the health care team needs to know [abstract no. 3000]. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol 2003; 22: 746

Catania C, Didier F, Sbanotto A, et al. Fully oral chemotherapy regimens: patient’s or physician’s preference [abstract no. 3122]. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol 2003; 22: 777

Waterhouse DM, Calzone KA, Mele C, et al. Adherence to oral tamoxifen: a comparison of patient self-report, pill counts, and microelectronic monitoring. J Clin Oncol 1993 Jun; 11(6): 1189–97

Partridge AH, Avorn J, Wang PS, et al. Adherence to therapy with oral antineoplastic agents. J Natl Cancer Inst 2002 May 1; 94(9): 652–61

Urquhart J, De Klerk E. Contending paradigms for the interpretation of data on patient compliance with therapeutic drug regimens. Stat Med 1998 Feb 15; 17(3): 251–67

Zeppetella G. How do terminally ill patients at home take their medication?. Palliat Med 1999 Nov; 13(6): 469–75

Iskedjian M, Einarson TR, MacKeigan LD, et al. Relationship between daily dose frequency and adherence to antihypertensive pharmacotherapy: evidence from a meta-analysis. Clin Ther 2002 Feb; 24(2): 302–16

Mu S, Ludden TM. Estimation of population pharmacokinetic parameters in the presence of non-compliance. J Pharmacokinet Pharmacodyn 2003 Feb; 30(1): 53–81

Cramer JA, Mattson RH, Prevey ML, et al. How often is medication taken as prescribed? A novel assessment technique. JAMA 1989 Jun 9; 261(22): 3273–7

De Tullio PL, Kirking DM, Arslanian C, et al. Compliance measure development and assessment of theophylline therapy in ambulatory patients. J Clin Pharm Ther 1987 Feb; 12(1): 19–26

Jonsson EN, Wade JR, Almqvist G, et al. Discrimination between rival dosing histories. Pharm Res 1997 Aug; 14(8): 984–91

Pullar T, Kumar S, Tindall H, et al. Time to stop counting the tablets?. Clin Pharmacol Ther 1989 Aug; 46(2): 163–8

Urquhart J. The electronic medication event monitor: lessons for pharmacotherapy. Clin Pharmacokinet 1997 May; 32(5): 345–56

Feldman HI, Hackett M, Bilker W, et al. Potential utility of electronic drug compliance monitoring in measures of adverse outcomes associated with immunosuppressive agents. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 1999 Jan; 8(1): 1–14

Rudd P. In search of the gold standard for compliance measurement. Arch Intern Med 1979 Jun; 139(6): 627–8

Levine AM, Richardson JL, Marks G, et al. Compliance with oral drug therapy in patients with hematologic malignancy. J Clin Oncol 1987 Sep; 5(9): 1469–76

Urquhart J. Role of patient compliance in clinical pharmacokinetics: a review of recent research. Clin Pharmacokinet 1994 Sep; 27(3): 202–15

Lim LL. Estimating compliance to study medication from serum drug levels: application to an AIDS clinical trial of zidovudine. Biometrics 1992 Jun; 48(2): 619–30

Rubio A, Cox C, Weintraub M. Prediction of diltiazem plasma concentration curves from limited measurements using compliance data. Clin Pharmacokinet 1992 Mar; 22(3): 238–46

Pullar T, Kumar S, Chrystyn H, et al. The prediction of steady-state plasma phenobarbitone concentrations (following low-dose phenobarbitone) to refine its use as an indicator of compliance. Br J Clin Pharmacol 1991 Sep; 32(3): 329–33

Vrijens B, Tousset E, Rode R, et al. Successful projection of the time course of drug concentration in plasma during a 1-year period from electronically compiled dosing-time data used as input to individually parameterized pharmacokinetic models. J Clin Pharmacol 2005 Apr; 45(4): 461–7

Santschi V, Wuerzner G, Schneider MP, et al. Clinical evaluation of IDAS II, a new electronic device enabling drug adherence monitoring. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 2007 Dec; 63(12): 1179–84

Duffull S, Denman M, Eccleston J, et al. WinPOPT user guide (version 1.1). Dunedin: University of Otago, 2006

Beal SL, Sheiner LB. The NONMEM system. Am Stat 1980; 34: 118–9

Beal SL, Sheiner LB. NONMEM user’s guides. San Francisco (CA): NONMEM Project Group, University of California, 1992

Insightful Corporation. S-Plus 6 user’s guide. Seattle (WA): Insightful Corporation, 2002

Widmer N, Decosterd LA, Csajka C, et al. Population pharmacokinetics of imatinib and the role of alpha-acid glycoprotein. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2006 Jul; 62(1): 97–112

Gieschke R, Reigner B, Blesch KS, et al. Population pharmacokinetic analysis of the major metabolites of capecitabine. J Pharmacokinet Pharmacodyn 2002 Feb; 29(1): 25–47

Reigner B, Blesch K, Weidekamm E. Clinical pharmacokinetics of capecitabine. Clin Pharmacokinet 2001; 40(2): 85–104

Wang W, Husan F, Chow SC. The impact of patient compliance on drug concentration profile in multiple doses. Stat Med 1996 Mar 30; 15(6): 659–69

Girard P, Sheiner LB, Kastrissios H, et al. Do we need full compliance data for population pharmacokinetic analysis?. J Pharmacokinet Biopharm 1996 Jun; 24(3): 265–82

Li J, Nekka F. A pharmacokinetic formalism explicitly integrating the patient drug compliance. J Pharmacokinet Pharmacodyn 2007 Feb; 34(1): 115–39

Lu J, Gries JM, Verotta D, et al. Selecting reliable pharmacokinetic data for explanatory analyses of clinical trials in the presence of possible noncompliance. J Pharmacokinet Pharmacodyn 2001 Aug; 28(4): 343–62

Kshirsagar SA, Blaschke TF, Sheiner LB, et al. Improving data reliability using a non-compliance detection method versus using pharmacokinetic criteria. J Pharmacokinet Pharmacodyn 2007 Feb; 34(1): 35–55

Gupta P, Hutmacher MM, Frame B, et al. An alternative method for population pharmacokinetic data analysis under noncompliance. J Pharmacokinet Pharmacodyn 2008 Apr; 35(2): 219–33

Soy D, Beal SL, Sheiner LB. Population one-compartment pharmacokinetic analysis with missing dosage data. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2004 Nov; 76(5): 441–51

Girard P, Blaschke TF, Kastrissios H, et al. A Markov mixed effect regression model for drug compliance. Stat Med 1998 Oct 30; 17(20): 2313–33

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Prof. Franck Chauvin for requesting a method to estimate compliance from pharmacokinetics, Dr Paul Kretchmer for editing the manuscript, and the reviewers whose advice helped to improve the manuscript. Pascal Girard is funded by INSERM (Paris, France). No sources of funding were used to assist in the preparation of this study. The authors have no conflicts of interest that are directly relevant to the content of this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hénin, E., Tod, M., Trillet-Lenoir, V. et al. Pharmacokinetically Based Estimation of Patient Compliance with Oral Anticancer Chemotherapies. Clin Pharmacokinet 48, 359–369 (2009). https://doi.org/10.2165/00003088-200948060-00002

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.2165/00003088-200948060-00002