Abstract

A good understanding of the mechanical behavior of functionally graded material (FGM) cylindrical shells is necessary for designers and researchers. However, the 3D transient response of FGM cylindrical shells under various boundary conditions has not yet been analyzed. In this paper, the problem is addressed by proposing an approach integrating the state space method, differential quadrature method, and Durbina’s numerical inversion method of Laplace transform. The laminate model is used to obtain the transient solution in the radial direction. At the edges, four kinds of boundary conditions are considered: Clamped-Clamped, Clamped-Simply supported, Clamped-Free, and Simply supported-Simply supported. The results of the proposed method and finite element (FE) method agree with each other excellently. Convergence studies show that the proposed method has a fast convergence rate. The natural frequencies obtained by the proposed method, experiment, and other theoretical methods are in close agreement with each other. The effects of the load frequency and duration, length/outer radius ratio, and the (outer radius-inner radius)/outer radius ratio on the transient response of FGM shells are investigated. Two laws of variation of material properties along the radial direction are considered: the first has material properties varying according to an exponential law along the radial direction, while the second has material properties varying according to a power law. The effect of a functionally graded index on the transient response of FGM shells is investigated in both cases. The results obtained in this paper can serve as benchmark data for further research.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Functionally graded material (FGM) has mechanical properties and volume fractions that vary gradually in one or two directions. Delamination caused by large inter-laminar stresses, and the initiation and propagation of cracks are avoided in FGMs (Carrera and Soave, 2011; Abbasnejad et al., 2013). Well tailored FGMs have much superiority over conventional composites (Wen et al., 2011; Liang et al., 2014). Recently, FGMs have gained a lot of popularity and been widely applied in various engineering fields, such as the aerospace industry, power industry, and civil engineering (Miyamoto et al., 1999; Liang et al., 2014; 2015a; Ng, 2014). As a common structural element, cylindrical shells have many advantages, such as a good strength to weight ratio, simple manufacture, savings in material cost, and large containment capability (Hosseini-Hashemi et al., 2012). Owing to their superior properties, cylindrical shells have been used in many engineering branches, such as aerospace, marine, civil, and nuclear engineering (Shadmehri et al., 2014). Therefore, a good understanding of the mechanical behavior of FGM cylindrical shells is necessary for designers and researchers.

The static and dynamic behavior of FGM cylindrical shells has been studied by employing many shell theories. Khdeir and Aldraihem (2011) developed analytical solutions for the static behavior of crossply smart laminated shells with extension piezoelectric laminae based on the rigorous first-order shell theory. Liew et al. (2012) studied the postbuckling of cylindrical shells under axial compression and thermal loads using the element-free kp-Ritz method and first-order shear deformation theory (FSDT). By employing a high order shear deformation shell theory, Shen and Wang (2013) carried out thermal buckling analysis on fiber reinforced cylindrical shells. Torki et al. (2014) studied the flutter of FGM cylindrical shells under distributed axial follower forces using FSDT. However, some displacement or stress variables are assumed to be zero in these shell theories, and the assumptions lead to numerical errors.

Some research has been devoted to 3D solutions which have no simplification in the thickness direction. For example, Neves et al. (2013) studied the free vibration behavior of FGM shells by radial basis functions collocation. They used the equations of motion and the boundary conditions obtained by Carrera’s Unified Formulation based on the principle of virtual work and further interpolated by collocation with radial basis functions. The state space method (SSM) satisfies all of the fundamental equations (Ying and Wang, 2009; Ying et al., 2009), and has been widely used for static and dynamic analyses of FGM cylindrical shells. Chen et al. (2004) studied the free vibration of an FGM cylinder filled with fluid. Hasheminejad and Rajabi (2008) performed an exact analysis for 3D scattering of a time-harmonic plane-progressive sound wave obliquely incident upon an arbitrarily thick bilaminated circular hollow cylinder of infinite extent. Tarn et al. (2009) carried out an exact analysis of a deformation and stress field in a finite circular elastic cylinder under its own weight. Alibeigloo and Liew (2014) presented an exact 3D free vibration solution for sandwich cylindrical panels with an FGM core.

The differential quadrature method (DQM) is an efficient numerical technique for initial and boundary problems (Bellman and Casti, 1971; Bert and Malik, 1996). Chen et al. (2003) integrated SSM and DQM for solving a free vibration problem. Lü et al. (2007) gave semi-analytical elasticity solutions for the bending of angle-ply laminates in cylindrical bending. Akbari Alashti and Khorsand (2012) performed 3D thermo-elastic analysis of FGM cylindrical shells with piezoelectric layers.

Research on the transient response of FGM structures have also been carried out (Wang et al., 2013a). Wang et al. (2007) developed a thermoelastic dynamic solution of a multilayered hollow cylinder in the state of axisymmetric plane strain, by employing the method of superposition. Some researchers carried out transient analysis on FGM rectangular plates, by employing SSM and Laplace transform (Wen et al., 2011; Zhou et al., 2011; Hasheminejad and Gheshlaghi, 2012; Wang et al., 2013b; Liang et al., 2015a). Wang (2013) developed a quasi-static approach for the transient thermal analysis of an FGM hollow cylinder using SSM and initial parameter method. Liang et al. (2015b) proposed a semianalytical method for the transient response of FGM rectangular plates by integrating SSM, DQM, and Laplace transform.

A comprehensive overview of the analytical method for the statics and dynamics of FGM cylindrical shells is carried out. To our knowledge, 3D analytical and semi-analytical methods for the transient response of FGM cylindrical shells with arbitrary boundary conditions have not been reported yet. In this paper, the problem is addressed by developing an approach that integrates the SSM, DQM, and Durbin (1974)’s numerical inversion method of Laplace transform. For the purpose of validation, the results obtained by the developed method and by the finite element (FE) method are compared. Convergence studies for different numbers of sampling points along the length direction and for different numbers of layers along the radial direction are carried out. Natural frequency studies are performed. The effects of the load frequency and duration, functionally graded index, length/outer radius ratio, and the (outer radius—inner radius)/outer radius ratio on the transient response of FGM cylindrical shells are investigated.

2 Problem description

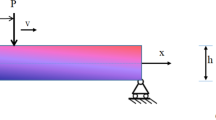

Consider a linear elastic FGM cylindrical shell of length l, inner radius b, and outer radius a. The problem geometry and the coordinate system are depicted in Fig. 1, where the (r, θ, z) frame is assumed to be located on the left surface of the shell. r and θ are in the radial and circumferential directions of the shell, respectively. z is perpendicular to the surface (r, θ). The mechanical properties are assumed to vary along the radial direction of the shell in an arbitrary fashion. It is assumed that the shell consists of K homogeneous layers of equal thickness.

Assuming every layer is orthotropic, the stress-displacement relationships for an arbitrary layer canbe expressed as

where

C ij (i, j=1, 2, ..., 6) represents the material elastic stiffness coefficients, σ r , σ θ , and σ z are the radial stress components, τ zθ , τ rz , and τ rθ are the shear stress components, and u r , u θ , and u z are the displacement components. In the absence of body forces, the governing equations of motion are

where ρ is the mass density.

2.1 Boundary conditions at the edges

Four different kinds of boundary conditions are considered here: Clamped-Clamped (C-C), Clamped-Simply supported (C-S), Clamped-Fee (C-F), and Simply supported-Simply supported (S-S).

Clamped (z=0)-Clamped (z=l):

Clamped (z=0)-Simply supported (z=l):

Clamped (z=0)-Free (z=l):

Simply supported (z=0)-Simply supported (z=l):

2.2 Boundary conditions at the inner and outer surfaces

The boundary conditions at the inner (r=b) and outer (r=a) surfaces are given as at the inner surface (r=b,

and at the outer surface (r=a),

where f θ and f z are the tangential traction forces, and f r is the normal traction force.

3 Semi-analytical solution

3.1 Normalization

The following normalized variables are now introduced:

where the over-vector ⇀ denotes the normalized value, t is the time, and the longitudinal wave velocity

The normalized displacement and stress components can be expanded into a Fourier series form as

where j=0, 1, 2, …, ∞ is the circumferential wave number, and the over-bar denotes the Fourier transformed function.

3.2 Applying Laplace transform and DQM

By substituting Eqs. (14)–(16) and employing the Laplace transform, the fundamental equations can be rewritten in terms of transformed Fourier and Laplace functions as

where

The induced variables in transformed domain are determined by

The DQM used in this study can be found in (Liang et al., 2015b). By applying DQM, the new state-space equations for the mth point are derived as

where \({\tilde \bar \sigma _{rm}} = {\tilde \bar \sigma _r}\left( {\mathord{\buildrel{\lower3pt\hbox{$\scriptscriptstyle\rightharpoonup$}} \over r} ,{{\mathord{\buildrel{\lower3pt\hbox{$\scriptscriptstyle\rightharpoonup$}} \over z} }_m},\mathord{\buildrel{\lower3pt\hbox{$\scriptscriptstyle\rightharpoonup$}} \over s} } \right),{\tilde \bar u_{rm}} = {\tilde \bar u_r}\left( {\mathord{\buildrel{\lower3pt\hbox{$\scriptscriptstyle\rightharpoonup$}} \over r} ,{{\mathord{\buildrel{\lower3pt\hbox{$\scriptscriptstyle\rightharpoonup$}} \over z} }_m},\mathord{\buildrel{\lower3pt\hbox{$\scriptscriptstyle\rightharpoonup$}} \over s} } \right), \ldots \) .

The induced variables for the mth sample point are determined by

By applying the DQM, Fourier and Laplace transform on Eqs. (4)–(11), the boundary conditions at the edges can be expressed as

-

Clamped (z=0)-Clamped (z=l):

$${\tilde \bar u_{r1}} = {\tilde \bar u_{\theta 1}} = {\tilde \bar u_{z1}} = 0,{\rm{ }}z = 0$$((22))$${\tilde \bar u_{rM}} = {\tilde \bar u_{\theta M}} = {\tilde \bar u_{zM}} = 0,{\rm{ }}z = l$$((23)) -

Clamped (z=0)-Simply supported (z=l): \({{\tilde \bar u}_{r1}} = {{\tilde \bar u}_{\theta 1}} = {{\tilde \bar u}_{z1}} = 0,{\rm{ }}z = 0\) \({{\tilde \bar \sigma }_{zM}} = {{\tilde \bar u}_{\theta M}} = {{\tilde \bar u}_{rM}} = 0,{\rm{ }}z = l\)

-

Clamped (z=0)-Free (z=l):

$${{\tilde \bar u}_{r1}} = {{\tilde \bar u}_{\theta 1}} = {{\tilde \bar u}_{z1}} = 0,{\rm{ }}z = 0$$((26))$${{\tilde \bar \sigma }_{zM}} = {{\tilde \bar \tau }_{z\theta M}} = {{\tilde \bar \tau }_{rzM}} = 0,{\rm{ }}z = l$$((27)) -

Simply supported (z=0)-Simply supported (z=l):

$${{\tilde \bar \sigma }_{z1}} = {{\tilde \bar u}_{\theta 1}} = {{\tilde \bar u}_{r1}} = 0,{\rm{ }}z = 0$$((28))$${{\tilde \bar \sigma }_{zM}} = {{\tilde \bar u}_{\theta M}} = {{\tilde \bar u}_{rM}} = 0,{\rm{ }}z = l$$((29))

Similarly, by applying the DQM, Fourier and Laplace transform to Eqs. (12) and (13), the boundary conditions at the inner and outer surfaces can be rewritten as

-

at the inner surface (r=b),

$${\tilde \bar \sigma _{rb}} = {\tilde \bar f_{rb}},{\rm{ }}{\tilde \bar \tau _{r\theta b}} = {\tilde \bar f_{\theta b}},{\rm{ }}{\tilde \bar \tau _{rzb}} = {\tilde \bar f_{zb}}$$((30)) -

and at the outer surface (r=a),

$${\tilde \bar \sigma _{ra}} = {\tilde \bar f_{ra}},{\rm{ }}{\tilde \bar \tau _{r\theta a}} = {\tilde \bar f_{\theta a}},{\rm{ }}{\tilde \bar \tau _{rza}} = {\tilde \bar f_{za}}$$((31))

where \({\tilde \bar \sigma _{rb}} = \left[ {{{\tilde \bar \sigma }_{r1}},{{\tilde \bar \sigma }_{r2}},{\rm{ }} \cdots ,{{\tilde \bar \sigma }_{rM}}} \right]_{r = b}^{\rm{T}},{\tilde \bar f_{\theta a}} = \left[ {{{\tilde \bar f}_{\theta 1}},{{\tilde \bar f}_{\theta 2}},{\rm{ }} \cdots ,{{\tilde \bar f}_{\theta M}}} \right]_{r = a}^{\rm{T}},{\rm{ }} \ldots \)

3.3 Semi-analytical solution

Eq. (20) is a differential equation with variable coefficients and is hard to solve. Therefore, an approximation is carried out to simplify the equations. The radial local coordinate ζ k , located at the center of the kth arbitrary layer is introduced here. Adopting an approximation ζ k /R k ≪1 in which each layer is viewed as a thin cylindrical shell, the following equations can be obtained by employing binomial series expansion (Alibeigloo and Shakeri, 2009):

where \({\xi _k} = r - {R_k}\) and \({\lambda _{k = }}{\xi _k}/{R_k}\) . According to Soong’s assumption (Soong, 1970), λ k can be neglected in comparison to unit (Jing and Tzeng, 1993; Alibeigloo and Shakeri, 2009). Hence, Eq. (20) can be rewritten in the following matrix form:

where \(\tilde \bar V = \left[ {{{\tilde \bar \sigma }_r},{{\tilde \bar u}_r},{{\tilde \bar u}_\theta },{{\tilde \bar u}_z},{{\tilde \bar \tau }_{rz}},{{\tilde \bar \tau }_{r\theta }}} \right],{{\tilde \bar \sigma }_r} = {\left[ {{{\tilde \bar \sigma }_{r1}},{{\tilde \bar \sigma }_{r2}}, \cdots ,{{\tilde \bar \sigma }_{rM}}} \right]^{\rm{T}}}{\rm{, }}{{\tilde \bar u}_{r1}} = {\left[ {{{\tilde \bar u}_{r1}},{{\tilde \bar u}_{r2}}, \cdots ,{{\tilde \bar u}_{rM}}} \right]^T},{\rm{ }} \ldots \) . The matrix H is given in Appendix A. After substituting Eqs. (22)–(29), the matrix H for different boundary conditions can be rewritten as shown in Appendix B.

The solution of Eq. (33) can be obtained as

where H k is the matrix H for the kth layer

Eq. (34) at λ=λk yields

where h k is the thickness of the kth layer

Subsequently,

Proceeding in the same manner for all K layers, the relation between the state vectors at the outer and inner surfaces of the FGM cylindrical shell is expressed as

where

Substituting the boundary conditions (30) and (31) at the outer and inner surfaces into Eq. (37) yields

where

After finding the nontrivial solution of Eq. (40), the solution in time domain can be obtained by applying the numerical inversion of Laplace transform. The algorithm for numerical inversion used in this paper can be found in (Cohen, 2007; Liang et al., 2015b).

4 Numerical results

For implementation, a Mathematica package was developed for the proposed method. Firstly, a comparison between the results obtained by the proposed method and the FE method was carried out to validate the proposed method. Subsequently, convergence studies were carried out. Lastly, the effects of the length/outer radius ratio (l/a), the (outer radius—inner radius)/outer radius ratio ((a–b)/a), and the functionally graded index γ were investigated.

4.1 Validation

To validate the proposed method, its results were compared to those obtained by FE method via commercial software ANSYS. The details of four cases considered are listed in Table 1.

The exponential variation law is given below:

where the over-hat denotes the corresponding value of material properties at r=a, and γ; is the functionally graded (FG) index.

The power variation law is given as

where VA(r) and VC(r) are the volume fractions of aluminum and ceramic zirconia, respectively. Thus, the elastic constants along the radial direction can be expressed as

where Cij,C and ρC are the elastic parameter and density of ceramic zirconia, and Cij,A and ρA are the elastic parameter and density of aluminum, respectively. The material properties of the two materials are given in Table 2 (Hasheminejad and Gheshlaghi, 2012).

Material properties ( Hasheminejad and Gheshlaghi, 2012 )

Subsequently, the material properties of the kth layer in the laminate model are given by

where k=1,2, …, K.

The load acting on the inner face of the cylindrical shell (r=b) is given by

where \({c_{\rm{A}}} = {\left( {{C_{33,{\rm{A}}}}/{\rho _{\rm{A}}}} \right)^{{1 \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {1 2}} \right. \kern-\nulldelimiterspace} 2}}}\) is the longitudinal wave velocity of aluminum.

For all four cases, the number M of sampling points along the z-direction and number of layers K along the radial direction are 21 and 4, respectively. The FE models for the four cases are given in Fig. 2. For the purpose of validation, the time histories of the normalized deflection \({u_r}/h\) at a chosen position \(\left( {x = \left( {a + b} \right)/2,y = 0,{\rm{ and }}z = h/2} \right)\) of FGM cylindrical shells subjected to transient loads obtained by the proposed method (SSM) and the FE analysis (FEA) are compared (Fig. 3). The results predicted by the two methods agree with each other, no matter which geometry, load, law of variation of material properties, FG index, or boundary condition is employed.

4.2 Convergence studies

To further illustrate the accuracy of our proposed method, convergence studies for different numbers of sampling points M along the length z-direction and for different numbers of layers K along the radial r-direction were carried out. The law of variation of material properties, FG index, load parameter, geometry of the cylindrical shell, and boundary conditions used in the convergence studies were the same as those in case 4 (Table 1).

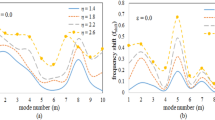

Firstly, a convergence study using different numbers of sampling points M along the z-direction was carried out. A series of numbers of sampling points M=7, 11, 17, 21, and 27 were used. The layer number q was fixed as 4. For all the five sampling point numbers, the time histories of the normalized deflection \({u_r}/h\) at a chosen position \(\left( {x = \left( {a + b} \right)/2,y = 0,{\rm{ and }}z = h/2} \right)\) of FGM cylindrical shells are plotted in Fig. 4a. The cases with M larger than 11 predicted nearly the same time histories, showing that the proposed method converges fast with increasing sampling points.

Secondly, a convergence study employing different numbers of layers along the radial direction was performed. A series of layer numbers of K=2, 4, 8, and 12 were employed. The sampling number was fixed as 21. For all four layer numbers, the time histories of the normalized deflection \({u_r}/h\) at a chosen position \(\left( {x = \left( {a + b} \right)/2,y = 0,{\rm{ and }}z = h/2} \right)\) of FGM cylindrical shells are plotted in Fig. 4b. The cases with K larger than 4 gave coincident time histories. We conclude that the proposed method has a rapid convergence rate with increasing layer numbers.

4.3 Natural frequency studies

To further demonstrate the reliability and accuracy of our proposed method, a homogeneous cylindrical shell with clamped-free boundary conditions was considered. Table 3 shows the results of our proposed method compared with those obtained by experiment (Sharma, 1984) and from other theoretical methods (Hosseini-Hashemi et al., 2013). Another homogeneous cylindrical shell with Clamped-Clamped boundary conditions was also considered. Table 4 shows the results of our proposed method compared with those obtained by experiment and from other theoretical methods (Leissa, 1973; Santos et al., 2009). The results obtained by our proposed method, experiment, and other theoretical methods agree with each other very well.

4.4 Effect of load frequency and duration

The effect of load frequency on the response of FGM cylindrical shells was investigated. Two cylindrical shells with Clamped-Clamped boundary condition and different thicknesses (cylindrical shell A: a−b=0.02 m and cylindrical shell B: a−b=0.04 m) were considered. The FG indexes γ, geometries loads, and boundary conditions were the same as those in case 3 (Table 1).

A natural frequency analysis was carried out and the results for the two cylindrical shells are listed in Table 5. Subsequently, the responses of the FGM cylindrical shells with a force \({f_{\rm{r}}} = \sin \left( {\omega t} \right)\) acting at a point \(\left( {\left( {a + b} \right)/2,{\rm{ 0, }}l} \right)\) were investigated by employing the proposed method. The ranges of the frequency ω for shells A and B were 0—300 Hz and 100—475 Hz, respectively. The amplitudes of displacements at a point \(\left( {\left( {a + b} \right)/2,{\rm{ 0, }}l/2} \right)\) of the two cylindrical shells are plotted in Figs. 5 and 6, respectively. The figures show that the cylindrical shells resonate at the natural frequency.

4.5 Effects of l/a and (a−b)/a

The effects of the length/outer radius ratio (l/a) and the (outer radius-inner radius)/outer radius ratio ((a−b)/a) on the transient response of FGM cylindrical shells were examined. The law of variation of material properties, FG index, load parameter, and boundary conditions used in this section were the same as those in case 4 (Table 1). The sampling number was 21 and the layer number was 4.

Firstly, the effect of l/a was investigated. A series of length/outer radius ratios l/a=1, 2, 4, and 8 were used. The outer radius a and inner radius b were fixed to be 1 and 0.98 m, respectively. Fig. 7a gives the time histories of the normalized deflection \({u_r}/h\) at a chosen position \(\left( {x = \left( {a + b} \right)/2,y = 0,{\rm{ and }}z = h/2} \right)\) of FGM cylindrical shells with different length/outer radius ratios l/a. The deflection of FGM cylindrical shells under this type of load increases as l/a increases.

Secondly, the effect of the (outer radius−inner radius)/outer radius ratio (a−b)/a was studied. A series of (outer radius−inner radius)/outer radius ratios (a−b)/a=0.02, 0.04, 0.08, and 0.16 were employed. The length and outer radius were fixed to be 1 and 1 m, respectively. Fig. 7b gives the time histories of the normalized deflection \({u_r}/h\) at a chosen position \(\left( {x = \left( {a + b} \right)/2,y = 0,{\rm{ and }}z = h/2} \right)\) of FGM cylindrical shells with different (a−b)/a. The deflection decreases as (a−b)/a increases.

4.6 Effect of functionally graded index

The effect of the FG index γ on the shell response was studied. The load parameter, geometry, and boundary conditions used in this section were the same as those in case 4 (Table 1). The sampling number was 21 and the layer number was 4.

Two laws of variation of material properties were considered. Under the law of exponential variation the material properties vary according to an exponential law, while under the law of power variation the material properties vary according to a power law, along the radial direction. For the exponential variation law, a series of FG parameters γ=5, 2, -2, and -5 were employed. For the power variation law, a series of FG parameters γ=5, 2, 0.5, and 0.2 were used.

For the two laws of variation of material properties, the time histories of the normalized deflection \({u_r}/h\) at a chosen position \(\left( {x = \left( {a + b} \right)/2,y = 0,{\rm{ and }}z = h/2} \right)\) of FGM cylindrical shells are given in Fig. 8. For the FGM shell with exponential variation law, the deflection of the shell decreases as the FG index γ increases. For the FGM shell with the power variation law, the deflection of the shell increases as the FG index γ increases.

5 Conclusions

A 3D semi-analytical method was proposed to analyze the transient response of FGM cylindrical shells. The boundary conditions at the edges can be arbitrary. The SSM, DQM, and Laplace transform and its numerical inversion method were integrated into the proposed method. The SSM was used to obtain a 3D analytical solution; the DQM was used to deal with the arbitrary boundary conditions at the edges; and the Laplace transform and its numerical inversion method were used to obtain solutions in time domain. At the edges, four kinds of boundary conditions were considered: C-C, C-S, C-F, and S-S.

A comparison between the results generated by the proposed method and by the FE method showed that the two methods predicted nearly the same results. Convergence studies were carried out. The proposed method showed a fast convergence rate with increasing sample number along the length direction and increasing layer number along the radial direction. The natural frequencies obtained by the proposed method, experiment, and other theoretical methods were in close agreement with each other. The effects of load frequency, load duration, length/outer radius ratio, and (outer radius−inner radius)/outer radius ratio on the transient response of FGM shells were investigated. The exponential and power laws of variation of material properties were considered. For the two laws of variation of material properties, the effect of functionally graded index on the transient response of FGM shells was investigated. The results obtained in this paper can serve as benchmark data in further research.

References

Abbasnejad, B., Rezazadeh, G., Shabani, R., 2013. Stability analysis of a capacitive FGM micro-beam using modified couple stress theory. Acta Mechanica Solida Sinica, 26(4):427–440. [doi:10.1016/S0894-9166(13)60038-5]

Akbari Alashti, R., Khorsand, M., 2012. Three-dimensional dynamo-thermo-elastic analysis of a functionally graded cylindrical shell with piezoelectric layers by DQ-FD coupled. International Journal of Pressure Vessels and Piping, 96–97:49–67. [doi:10.1016/j.ijpvp.2012.06.006]

Alibeigloo, A., Shakeri, M., 2009. Elasticity solution for static analysis of laminated cylindrical panel using differential quadrature method. Engineering Structures, 31(1): 260–267. [doi:10.1016/j.engstruct.2008.08.012]

Alibeigloo, A., Liew, K.M., 2014. Free vibration analysis of sandwich cylindrical panel with functionally graded core using three-dimensional theory of elasticity. Composite Structures, 113:23–30. [doi:10.1016/j.compstruct.2014.03.004]

Bellman, R., Casti, J., 1971. Differential quadrature and longterm integration. Journal of Mathematical Analysis and Applications, 34(2):235–238. [doi:10.1016/0022-247X(71)90110-7]

Bert, C.W., Malik, M., 1996. Differential quadrature method in computational mechanics: a review. Applied Mechanics Reviews, 49(1):1–28. [doi:10.1115/1.3101882]

Carrera, E., Soave, M., 2011. Use of functionally graded material layers in a two-layered pressure vessel. Journal of Pressure Vessel Technology, 133(5):051202. [doi:10.1115/1.4003458]

Chen, W.Q., Lv, C.F., Bian, Z.G., 2003. Elasticity solution for free vibration of laminated beams. Composite Structures, 62(1):75–82. [doi:10.1016/S0263-8223(03)00086-2]

Chen, W.Q., Bian, Z.G., Lv, C.F., et al., 2004. 3D free vibration analysis of a functionally graded piezoelectric hollow cylinder filled with compressible fluid. International Journal of Solids and Structures, 41(3–4):947–964. [doi:10.1016/j.ijsolstr.2003.09.036]

Cohen, A.M., 2007. Numerical Methods for Laplace Transform Inversion. Springer Science & Business Media.

Durbin, F., 1974. Numerical inversion of Laplace transforms: an efficient improvement to Dubner and Abate’s method. The Computer Journal, 17(4):371–376. [doi:10.1093/comjnl/17.4.371]

Hasheminejad, S.M., Rajabi, M., 2008. Scattering and active acoustic control from a submerged piezoelectric-coupled orthotropic hollow cylinder. Journal of Sound and Vibration, 318(1–2):50–73. [doi:10.1016/j.jsv.2008.04.005]

Hasheminejad, S.M., Gheshlaghi, B., 2012. Threedimensional elastodynamic solution for an arbitrary thick FGM rectangular plate resting on a two parameter viscoelastic foundation. Composite Structures, 94(9): 2746–2755. [doi:10.1016/j.compstruct.2012.04.010]

Hosseini-Hashemi, S., Ilkhani, M.R., Fadaee, M., 2012. Identification of the validity range of Donnell and sanders shell theories using an exact vibration analysis of functionally graded thick cylindrical shell panel. Acta Mechanica, 223(5):1101–1118. [doi:10.1007/s00707-011-0601-0]

Hosseini-Hashemi, S., Ilkhani, M.R., Fadaee, M., 2013. Accurate natural frequencies and critical speeds of a rotating functionally graded moderately thick cylindrical shell. International Journal of Mechanical Sciences, 76:9–20. [doi:10.1016/j.ijmecsci.2013.08.005]

Jing, H.S., Tzeng, K.G., 1993. Approximate elasticity solution for laminated anisotropic finite cylinders. AIAA Journal, 31(11):2121–2129. [doi:10.2514/3.11899]

Khdeir, A.A., Aldraihem, O.J., 2011. Exact analysis for static response of cross ply laminated smart shells. Composite Structures, 94(1):92–101. [doi:10.1016/j.compstruct.2011.07.013]

Leissa, A.W., 1973. Vibration of shells. Scientific and Technical Information Office, National Aeronautics and Space Administration, Washington.

Liang, X., Wang, Z., Wang, L., et al., 2014. Semi-analytical solution for three-dimensional transient response of functionally graded annular plate on a two parameter viscoelastic foundation. Journal of Sound and Vibration, 333(12):2649–2663. [doi:10.1016/j.jsv.2014.01.021]

Liang, X., Wang, Z., Wang, L., et al., 2015a. A semianalytical method to evaluate the dynamic response of functionally graded plates subjected to underwater shock. Journal of Sound and Vibration, 336:257–274. [doi:10. 1016/j.jsv.2014.10.013]

Liang, X., Wu, Z., Wang, L., et al., 2015b. Semianalytical three-dimensional solutions for the transient response of functionally graded material rectangular plates. Journal of Engineering Mechanics, 04015027. [doi:10.1061/(ASCE)EM.1943-7889.0000908]

Liew, K.M., Zhao, X., Lee, Y.Y., 2012. Postbuckling responses of functionally graded cylindrical shells under axial compression and thermal loads. Composites Part B: Engineering, 43(3):1621–1630. [doi:10.1016/j.compositesb.2011.06.004]

Lü, C.F., Lim, C.W., Xu, F., 2007. Stress analysis of anisotropic thick laminates in cylindrical bending using a semi-analytical approach. Journal of Zhejiang University-SCIENCE A, 8(11):1740–1745. [doi:10.1631/jzus.2007. A1740]

Miyamoto, Y., Kaysser, W.A., Rabin, B.H., et al., 1999. Functionally Graded Materials: Design, Processing and Applications. Kluwer Academic Publishers, Boston. [doi:10.1007/978-1-4615-5301-4]

Neves, M.A., Ferreira, J.M., Carrera, E., et al., 2013. Free vibration analysis of functionally graded shells by a higher-order shear deformation theory and radial basis functions collocation, accounting for through-thethickness deformations. European Journal of Mechanics -A/Solids, 37:24–34. [doi:10.1016/j.euromechsol.2012.05.005]

Ng, C.W.W., 2014. The state-of-the-art centrifuge modelling of geotechnical problems at HKUST. Journal of Zhejiang University-SCIENCE A (Applied Physics & Engineering), 15(1):1–21. [doi:10.1631/jzus.A1300217]

Santos, H., Mota Soares, C.M., Mota Soares, C.A., et al., 2009. A semi-analytical finite element model for the analysis of cylindrical shells made of functionally graded materials. Composite Structures, 91(4):427–432. [doi:10.1016/j.compstruct.2009.04.008]

Shadmehri, F., Hoa, S., Hojjati, M., 2014. The effect of displacement field on bending, buckling, and vibration of cross-ply circular cylindrical shells. Mechanics of Advanced Materials and Structures, 21(1):14–22. [doi:10. 1080/15376494.2012.677102]

Sharma, C.B., 1984. Free vibrations of clamped-free circular cylinders. Thin-Walled Structures, 2(2):175–193. [doi:10.1016/0263-8231(84)90011-9]

Shen, H.S., Wang, H., 2013. Thermal postbuckling of functionally graded fiber reinforced composite cylindrical shells surrounded by an elastic medium. Composite Structures, 102:250–260. [doi:10.1016/j.compstruct.2013.03.011]

Soong, T.V., 1970. A sub divisional method for linear system. Proceedings of the 11th AIAA/ASME Structures, Structural Dynamics and Material Conferences, New York, p.211–223.

Tarn, J.Q., Tseng, W.D., Chang, H.H., 2009. A circular elastic cylinder under its own weight. International Journal of Solids and Structures, 46(14–15):2886–2896. [doi:10. 1016/j.ijsolstr.2009.03.016]

Torki, M.E., Kazemi, M.T., Reddy, J.N., et al., 2014. Dynamic stability of functionally graded cantilever cylindrical shells under distributed axial follower forces. Journal of Sound and Vibration, 333(3):801–817. [doi:10.1016/j.jsv.2013.09.005]

Wang, H.M., 2013. An effective approach for transient thermal analysis in a functionally graded hollow cylinder. International Journal of Heat and Mass Transfer, 67:499–505. [doi:10.1016/j.ijheatmasstransfer.2013.08.043]

Wang, H.M., Ding, H.J., Ge, W., 2007. Transient responses in a two-layered elasto-piezoelectric composite hollow cylinder. Composite Structures, 79(2):192–201. [doi:10.1016/j.compstruct.2005.12.005]

Wang, Z., Liang, X., Liu, G., 2013a. An analytical method for evaluating the dynamic response of plates subjected to underwater shock employing Mindlin plate theory and Laplace transforms. Mathematical Problems in Engineering, 2013:803609. [doi:10.1155/2013/803609]

Wang, Z., Liang, X., Fallah, A.S., et al., 2013b. A novel efficient method to evaluate the dynamic response of laminated plates subjected to underwater shock. Journal of Sound and Vibration, 332(21):5618–5634. [doi:10.1016/j.jsv.2013.05.028]

Wen, P.H., Sladek, J., Sladek, V., 2011. Three-dimensional analysis of functionally graded plates. International Journal for Numerical Methods in Engineering, 87(10): 923–942. [doi:10.1002/nme.3139]

Ying, J., Wang, H.M., 2009. Magnetoelectroelastic fields in rotating multiferroic composite cylindrical structures. Journal of Zhejiang University-SCIENCE A, 10(3):319–326. [doi:10.1631/jzus.A0820517]

Ying, J., Lu, C.F., Lim, C.W., 2009. 3D thermoelasticity solutions for functionally graded thick plates. Journal of Zhejiang University-SCIENCE A, 10(3):327–336. [doi:10.1631/jzus.A0820406]

Zhou, F., Li, S., Lai, Y., 2011. Three-dimensional analysis for transient coupled thermoelastic response of a functionally graded rectangular plate. Journal of Sound and Vibration, 330(16):3990–4001. [doi:10.1016/j.jsv.2011.03.015]

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Project supported by the National Basic Research Program (973 Program) of China (No. 2013CB035901), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 51209185, 51079127, 51179171, 51279180, and 51379185), the International Postdoctoral Exchange Fellowship Program, and the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (No. 2013M531462)

ORCID: Xu LIANG, http://orcid.org/0000-0002-1268-7036; Hailei KOU, http://orcid.org/0000-0003-2545-1652

Appendices

Appendix A

Appendix B

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Liang, X., Kou, Hl., Liu, Gh. et al. A semi-analytical state-space approach for 3D transient analysis of functionally graded material cylindrical shells. J. Zhejiang Univ. Sci. A 16, 525–540 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1631/jzus.A1500016

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1631/jzus.A1500016

Key words

- State space method

- Numerical inversion of Laplace transform

- Differential quadrature method

- Functionally graded material (FGM)

- Cylindrical shells