Abstract

We provide an overview of the field of rigidity theory applied at the atomic scale. This theoretical approach, initially designed for macroscopic structures such as bridges or buildings, has gained renewed interest in the past few years thanks to new methodological developments and to attractive applications in a variety of materials, such as scratch-resistant glassy sheets for mobile phones, phase-change memory, tough cement, dielectrics, and photonic devices. In parallel, basic phenomena associated with the onset of rigidity have been discovered, which have challenged our current understanding of the structural modification induced by changes in composition. This has led to the identification of “smart” glasses with multiple functionalities and superior mechanical performances. Topological prediction and engineering of physical properties are also enabling intelligent design of new disordered materials.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The link between the pioneering work of J.C. Maxwell on trusses, engineered constructions such as bridges, electric towers, and space structures, and the modern design of complex materials at the atomic scale is not obvious at first glance. Such macroscopic structures are always composed of a number of bars, connected by pins at their ends, to form a stable framework made of nodes and bars. The way loads and reactions affect the stability of the construction is determined by equations of statics applied on each node with the bar tension being the relevant force. These important contributions were fostered from the concept of mechanical constraints introduced by Lagrange1 in the late eighteenth century and Cauchy2 in 1823.

Ultimately, the density, nc, of such mechanical constraints arising from such force tensions can be compared to the number of degrees of freedom, nd, per node, and trusses fulfilling nc = nd are said to be “isostatic.” For obvious reasons, applications in civil engineering always work with nc > nd; in other words, the structure is maintained rigid, reinforced by redundant bars in order to avoid the possibility of mechanical deformations that may induce failure and structural collapse. But how does this connect to material properties at the atomic scale?

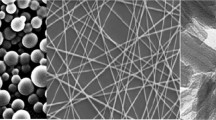

Inspired by the pioneering work of Maxwell, at the beginning of the 1980s, Phillips3 and Thorpe4 proposed applying the analysis of trusses to disordered molecular networks such as glasses or amorphous solids that exhibit a lack of periodicity at long range, but have some structural order at short range ( Figure 1). Corresponding materials were then viewed in terms of their topological and rigidity properties, involving in most cases the way atoms connect, and, more importantly, the way they interact. The transposition appears to be somewhat obvious—nodes are replaced by atoms and the bar tensions are replaced by the most relevant interactions at the molecular level, namely two-body radial and three-body angular interactions resulting in stretching and bending motions. Using the tools provided by structural rigidity, which predicts the flexibility of ensembles formed by rigid bodies connected by flexible linkages or hinges, the mechanical properties of glassy networks could be calculated from the enumeration of constraints at zero temperature.

Mean-field molecular rigidity

In the simplest (mean-field) version of the application of rigidity theory,3,4 for an r -coordinated atom, the enumeration of bond-stretching and bond-bending forces gives r/2 and (2 r – 3) constraints, respectively. The latter is obtained by considering a twofold atom (i.e., an atom with two bonds, r = 2), which has only one single angular constraint. Each additional bond onto this atom needs the definition of two additional constraints. The total number of constraints, nc, per atom in a material having different r -fold coordinated species with concentration nr is, therefore:

Detail of Gustave Eiffel’s plan shows that the well-known Paris construction is a node and bar framework. An analogy can be made at the microscopic scale, where the nodes are replaced by atoms and the bars by covalent bonds. For ease of calculation, rather than focusing on ordered networks, the authors of the initial rigidity approach preferred averaging over disorder to achieve mean-field rigidity.

With the definition of an important quantity, the mean coordination number of the network:

it is easy to verify that the condition of an iso-static network nc = nd = 3 in three dimensions (3D) can be obtained for the mean coordination number 〈r〉 = 2.4, which defines an elastic phase transition between a flexible network and a stressed-rigid one.

Here, the quantity 〈r〉 acts as a control parameter for the transition as the temperature in an ordinary ferromagnetic phase transition. The difference f = 3 − nc representing the density of flexible (floppy) modes is the order parameter. The flexibility/rigidity of such a network is then deduced from the stretching or bending of bonds between neighboring atoms, which serve as mechanical constraints. In 3D space, each atom has three translational degrees of freedom. These can be removed through the presence of such rigid bond constraints.

For select systems in which the octet or 8- N rule can be used with confidence, N being the number of outer shell electrons, the application of such ideas and concepts have proven to be remarkably successful ( Figure 2).3 For instance, in multicomponent chalcogenide glasses containing an important fraction of Group VI elements (S, Se, Te) or in multicomponent oxides, such rules permit determining the flexible-to-rigid transition due to the presence of anomalies or thresholds in various physicochemical properties, as detected from Raman scattering,5 stress relaxation and viscosity measurements,6 vibrational density of states,7 Brillouin scattering,8 and resistivity.9 However, for many other systems, including the important classes of oxides, silicates, or borosilicates, which represent the base material for many domestic and industrial applications in glass science, the question of a well-defined coordination number has been a long-standing issue. This has been resolved10 with the support of molecular dynamics (MDs)-based constraint-counting algorithms that have permitted extension of our understanding to the next level.

In summary, this practical computational scheme, the Maxwell constraint counting procedure, has been central to many contemporary calculations in noncrystalline solids, particularly on chalcogenide and oxide glasses. Larger challenges remain, however, as discussed in the articles in this issue of MRS Bulletin , focusing on the need to improve the approximate mean-field procedure, and to increase applicability of constraint-counting algorithms to new complex materials. We hope that the advances discussed in this issue will help connect the importance of rigidity theory of glasses to material properties and functionalities, and eventually clarify a number of aspects as described next.

With an appropriate alloying or applied pressure, the connectivity and number of mechanical constraints (radial and angular interactions) can be increased, thereby driving a flexible disordered network into a stressed-rigid one. For selected compositions corresponding to isostatic reversibility windows (RWs) or intermediate phases, an anomalous behavior is obtained for various physical quantities that serve for special materials design-enthalpy with small changes under aging in the RWs, reduced molar volume, low fragility, and enhanced fracture toughness. Ionic conductivity increases exponentially in flexible solid electrolytes.

Recent advances in application of rigidity theory

While the application of rigidity theory has its own interest in the field of mathematical physics, including percolation or graph theory with applications in basic science,11 it should be emphasized that important progress in materials design has also emerged in the recent years from increased applicability of rigidity theory at the atomic scale. This has been mostly achieved from three independent breakthroughs that we briefly outline here, with detailed descriptions to follow in the articles of this issue. The descriptions of these important breakthroughs and recent applications to various materials represent the core of this theme issue of MRS Bulletin.

Applications using molecular rigidity have led to the design of complex materials such as Corning’s widely known Gorilla Glass 3 that has served as a robust scratchproof glass in mobile phones and other flat-panel displays. Similarly, concepts from rigidity have been used to identify promising calcium–silicate–hydrate (CSH) compositions that form the binding phase of concrete. By analyzing the rigidity of more than 150 simulated CSH compositions, the elastic properties of these cements have been predicted as a function of composition,12 based on the number of radial and angular constraints. Among other results, it has been discovered that isostatic CSHs show an optimal fracture resistance and are reversible under compression. Using the same tools, researchers at Intel have realized that insulating materials with progressively lower dielectric constants can be optimized from the underlying rigidity properties of the Si-C:H network13 in order to minimize capacitive-related power losses in integrated circuits.

Temperature dependence

Previous applications of rigidity were performed on a fully connected network,1,2 a condition that is only valid at zero temperature. At nonzero temperatures, however, a constraint can soften depending on the amount of available thermal energy compared with the amount of energy required to break the constraint. Mauro and collaborators14,15,16 have extended the initial Phillips–Thorpe theory to quantitatively account for the effect of temperature. Moreover, they have been able to explicitly derive the nc dependence of various physicochemical properties, a result which has been considered a major step forward because previously, the theory was only able to predict the location of thresholds or transitions, not the property itself.

The incorporation of this explicit temperature dependence in rigidity theory has facilitated the design of glasses with superior toughness, and has led to an increased understanding of the effects of composition on the glass transition and the dynamical slowing down of viscous flow. It is fascinating that the hardness of glass and glass-transition temperature can be precisely predicted using rigidity theory.15 A large part of these contributions is discussed in this issue, especially in the article by Smedskjaer et al. It is worth mentioning that this has not only led to superior glass properties, but has also optimized glass production processes.

Thermally stable glasses

The determination of the mean-field rigidity transition predicted by Phillips and Thorpe has all the characteristics of deceitful simplicity. In fact, the experimental discovery of stable isostatic (neither flexible, nor stressed-rigid) glasses at select compositions and thermodynamic conditions has challenged the current understanding of elastic phase transitions in disordered networks.5 The discovery of two thresholds or two transitions by the Boolchand group has also challenged the common view of the solitary mean-field transition, and results or consequences are still being actively debated in the literature. However, it has now become clear that such intriguing effects seem to result from adaptation or self-organization at the molecular level, in order to avoid the stresses imposed by increased bond density.17

Apart from these more basic aspects of rigidity transitions, with the important body of data accumulated on chalcogenide and oxide glasses in the past few years, it has now also become evident that such isostatic glassy compositions defining an “intermediate phase” display a certain number of quite remarkable properties, such as an enhanced stability with respect to aging,18 space-filling tendencies,19 stress-free character,20 and glass transitions with minimum enthalpic changes.5 Undoubtedly, such anomalous properties will be used in the near future for the design of dedicated functionalities. In their article in this issue, Boolchand and Goodman describe a certain number of important consequences.

MDs-based constraint counting

As previously stated, MD simulations have now also permitted extension of the constraint enumeration to materials that have a complex bonding scheme that does not always permit the use of the octet rule, while also leading to the consideration of other thermodynamic conditions such as pressure or temperature.

Such simulations are routinely used to model the structure of materials with steadily increasing accuracy. A different approach can be taken, however, and one can instead examine the spread in bond lengths and bond-angle variations from the generated MD trajectories, or more precisely, the second moment of their distributions.10 This second moment is found to be small for select neighbors as anticipated, but large for all others given that “well-defined” bond distances and bond angles imposed by constraints will yield “well-defined” or narrow distributions. While the definition of coordination numbers of cations and anions in Ge and As selenides or sulfides are not much in doubt, the same cannot be said of the corresponding tellurides, where the 8- N bonding rule is known to be intrinsically broken. Using such improved tools, the elastic phase diagram of the phase-change materials could be predicted.21

Given the general use of such simulations, classical or ab initio , for the description of complex materials, the MD-based enumeration of constraints now offers the possibility to rationalize the design of new families of materials using the rigidity state of the underlying atomic network as input,22 as recently demonstrated for cements,12 and also described in the Bauchy article in this issue.

A variety of applications

Several major scientific communities (materials science, electrical engineering, and computer science) have a strong interest in the structure and compositionally induced structural changes in disordered or partially ordered materials. Here, we review some of the more promising applications ( Figure 3). These are extensively described in the articles in this issue.

The application of constraint-counting algorithms has proved to be useful in the understanding of thin-film gate dielectrics in electrical engineering. Specifically, at the Si-SiO2 interface, the first two monolayers adjacent to the Si substrate are optimally constrained and display features that are typical of isostatic glasses.23 Similarly, innovative semiconductors (e.g., SiC) with a reduced capacitive power loss can be optimized and designed by tuning the rigidity of the relevant materials upon select hydrogenation.13 In their article, Paquette et al. describe the work that is being developed at Intel Corporation. Amorphous materials also find use in solid-state batteries, sensors, and nonvolatile memories for portable devices; recent approaches using molecular rigidity have opened new avenues to understand the effects of rigidity on the functionalities of these devices. For instance, it has been discovered that molecular flexibility promotes mobility and ion conduction in solid electrolytes.24 This suggests that increased conductivity in batteries, a critical issue, can be achieved by several strategies, either by lowering network rigidity, or by increasing the fraction of ionic carriers.

Materials functionalities undergo systematic improvements that are essentially driven by changes in composition or additional alloying. In this broad context, guidance from molecular rigidity is particularly helpful. From a starting network structure, a constraint count is performed from the topology, and the effect of composition on properties is investigated. This general framework finds applications in glass science, civil engineering, electrical engineering, and optoelectronics, as well as in biology.

Chalcogenide thin films transmit in the infrared and display profound photostructural transformations that have opened new technologies in the areas of information storage, optomechanical devices, harmonic generation, and photochemical etching. Applications of rigidity theory have permitted rationalization of photostructural transformations in the context of data storage.22,25 An especially interesting application deals with materials forming the active elements of nonvolatile, highly power-efficient, fast memory devices currently used for portable electronics. Piarristeguy et al. describe some of these aspects in their article in this issue.

In their article, Zhou and Qiu describe how topological engineering has been found to be an effective approach toward high-performance photonic glasses, especially luminescent glasses.26 This approach enables modulating the chemical state of dopants (e.g., transition or rare-earth metals) in glass and tuning their local crystal field around active dopants.

Rigidity theory has also found interesting applications in earth sciences. It has been found that modified silicates display the same salient features of rigidity, with a phenomenology that is close to that observed in chal-cogenides. As magmatic liquids are made of the basic network former SiO2 and different modifiers (Al2O3, Na2O, CaO), the creation of nonbridging oxygens as in ionic Na O− bonds leads to depolymerization of a network to produce substantial variations in viscosity. There is recent experimental and numerical work to show that pressurized silica and germania are isostatic inside a pressure window,27 in which temperature-induced densification is manifested.

Finally, intermediate phases are thought to be found in a number of other disciplines of scientific inquiry and are suggested to be generic for complex network adaptation. Protein folding,28 feasibility problems in computer science,29 and the origin of pairing in high-Tc superconductors30 have been mentioned as being the manifestation of a self-organized rigidity, far from a simple formal analogy, which endows them with a special functionality.

Conclusions

Modern applications of Maxwell’s contributions have led to nascent, intense, and multifaceted research activities, and we believe that this issue of MRS Bulletin on the relationship between functionality and molecular rigidity will stimulate broad interest in the materials community at large. Given the general character of the concepts, other new and unexpected applications are likely to emerge. The various contributions in this issue are by leading experts in this field. They show how recent reformulations of the initial concepts have fostered the design and emergence of promising high-technology materials.

Among these materials, there is of course active interest in glass science and glass products that can be derived from such approaches. Progress in glass science depends much on identification of “select” compositions. In addition, with the help of MD-based design, there is an increased possibility to consider other classes of materials. Recent MD simulations on water contamination of glasses demonstrate, for example, that stressed-rigid systems show limited reactivity, while surfaces of flexible systems are far more reactive.31 On the opposite end, rigid systems show increased chemical durability of their surfaces. There is, thus, an interesting perspective to tune the composition of a material in order to achieve targeted surface properties.

In summary, there are new and exciting opportunities of an interdisciplinary character building on the concepts of molecular rigidity. From glass windows and light bulbs to lenses and fiberglass insulation, advances in glass science and technology have indisputably played a vital role in enabling modern civilization. The properties and performance of every glass product, especially high-technology glasses such as optical fibers, amorphous phase change DVDs, or scratch-resistant flat-panel displays, including mobile phones, are governed by underlying principles of flexibility/rigidity of the glass networks. Understanding the relationship between glass functionality and network rigidity holds the promise to enable design of glassy solids, thin films, and nanostructures for new applications. With the help of molecular simulations, such ideas and concepts can now be extended to a much larger variety of materials, in addition to glasses, as recently highlighted by the applications to cement,18,31 photonic, and dielectric materials.

References

J.-L. Lagrange, Mécanique Analytique (Paris, 1788).

A. Cauchy, Bull. Société Philomathique 26, 1823.

J.C. Phillips, J. Non Cryst. Solids 34, 153 (1979).

H. He, M.F. Thorpe, Phys. Rev. Lett. 54, 2107 (1985).

D. Selvenathan, W. Bresser, P. Boolchand, Phys. Rev. B Condens. Matter 61, 15061 (2000).

M. Tatsumisago, B.L. Halfpap, J.L. Green, S.M. Lindsay, C.A. Angell, Phys. Rev. Lett. 64, 1549 (1990).

W.A. Kamitakahara, R.L. Cappelletti, P. Boolchand, B. Halfpap, E. Gompf, D.A. Neumann, H. Mutka, Phys. Rev. B Condens. Matter 44, 94 (1991).

J. Gump, I. Finkler, H. Xia, R. Sooryakumar, W.J. Bresser, P. Boolchand, Phys. Rev. Lett. 92, 245501 (2004).

S. Asokan, M.Y.N. Prasad, G. Parthasarathy, Phys. Rev. Lett. 62, 808 (1989).

M. Bauchy, M. Micoulaut, J. Non Cryst. Solids 357, 2530 (2011).

M.F. Thorpe, P.M. Duxbury, Eds., Rigidity Theory and Applications (Plenum Press, New York, 1999).

M. Bauchy, M.J.A. Qomi, C. Bichara, F.J. Ulm, R.J.M. Pellenq, Phys. Rev. Lett. 114,125502 (2015).

S.W. King, J. Bielefeld, G. Xu, W.A. Lanford, Y. Matsuda, R.H. Dauskardt, N. Kim, D. Hondongwa, L. Olasov, B. Daly, G. Stan, M. Liu, D. Dutta, D. Gidley, J. Non Cryst. Solids 379, 67 (2013).

P.K. Gupta, J.C. Mauro, J. Chem. Phys. 130, 094503 (2009).

M.S. Smedskjaer, J.C. Mauro, R.E. Youngman, C.L. Hogue, M. Potuzak, Y.Z. Yue, J. Phys. Chem. B 115,12930 (2011).

M.M. Smedskjaer, J.C. Mauro, Y.Z. Yue, Phys. Rev. Lett. 105, 115503 (2010).

M. Micoulaut, J.C. Phillips, Phys. Rev. B Condens. Matter 67, 104204 (2003).

S. Chakravarty, D.G. Georgiev, P. Boolchand, M. Micoulaut, J. Phys. Cond. Matter 17, L7 (2005).

C. Bourgel, M. Micoulaut, M. Malki, P. Simon, Phys. Rev. B Condens. Matter 79, 024201 (2009).

F. Wang, S. Mamedov, P. Boolchand, B. Goodman, M. Chandrasekhar, Phys. Rev. B Condens. Matter 71, 174201 (2005).

M. Micoulaut, C. Otjacques, J.-Y. Raty, C. Bichara, Phys. Rev. B Condens. Matter 81, 174206 (2010).

C. Yildirim, J.-Y. Raty, M. Micoulaut, Nat. Commun. 7, 11086 (2016)

G. Lucovsky, J.C. Phillips, Appl. Phys. 78, 453 (2004).

M. Micoulaut, M. Malki, D.I. Novita, P. Boolchand, Phys. Rev. B Condens. Matter 80, 184205 (2009).

J. Luckas, A. Olk, P. Jost, H. Volker, J. Alvarez, A. Jaffré, P. Zalden, A. Piarristeguy, A. Pradel, C. Longeaud, M. Wuttig, Appl. Phys. Lett. 105, 092108 (2014).

S. Zhou, Q. Guo, H. Inoue, Q. Ye, A. Masuno, B. Zheng, Y. Yu, J. Qiu, Adv. Mater. 26, 7966 (2014).

K. Trachenko, M.T. Dove, V.V. Brazhkin, F.S. Elkin, Phys. Rev. Lett. 93, 135502 (2004).

A.J. Rader, B. Hespenheide, L. Kuhn, M.F.Thorpe, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99, 3540 (2002).

R. Monasson, R. Zecchina, S. Kirkpatrick, B. Selman, L. Troyansky, Nature 400, 133 (1999).

J.C. Phillips, Phys. Rev. B Condens. Matter 71, 184505 (2005).

I. Pignatelli, A. Kumar, M. Bauchy, G. Sant, Langmuir 32, 4434 (2016).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Micoulaut, M., Yue, Y. Material functionalities from molecular rigidity: Maxwell’s modern legacy. MRS Bulletin 42, 18–22 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1557/mrs.2016.298

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1557/mrs.2016.298