Abstract

To date, information on the ontogeny of renal transporters is limited. Here, we propose to estimate the in vivo functional ontogeny of transporters using a combined population pharmacokinetic (popPK) and physiology-based pharmacokinetic (PBPK) modeling approach called popPBPK. Clavulanic acid and amoxicillin were used as probes for glomerular filtration, combined glomerular filtration, and active secretion through OAT1,3, respectively. The predictive value of the estimated OAT1,3 ontogeny function was assessed by PBPK predictions of renal clearance (CLR) of other OAT1,3 substrates: cefazolin and piperacillin. Individual CLR post-hoc values, obtained from a published popPK model on the concomitant use of clavulanic acid and amoxicillin in critically ill children between 1 month and 15 years, were used as dependent variables in the popPBPK analysis. CLR was re-parameterized according to PBPK principles, resulting in the estimation of OAT1,3-mediated intrinsic clearance (CLint,OAT1,3,invivo) and its ontogeny. CLint,OAT1,3,invivo ontogeny was described by a sigmoidal function, reaching half of adult level around 7 months of age, comparable to findings based on renal transporter-specific protein expression data. PBPK-based CLR predictions including this ontogeny function were reasonably accurate for piperacillin in a similar age range (2.5 months–15 years) as well as for cefazolin in neonates as compared to published data (%RMSPE of 21.2 and 22.8%, respectively and %PE within ±50%). Using this novel approach, we estimated an in vivo functional ontogeny profile for CLint,OAT1,3,invivo that yields accurate CLR predictions for different OAT1,3 substrates across different ages. This approach deserves further study on functional ontogeny of other transporters.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

INTRODUCTION

Pediatric renal clearance (CLR) is driven by physiology related changes to kidney size, number of glomeruli and nephron filtration capacity, renal blood flow, expression of drug binding plasma proteins and expression of transporters. Throughout the pediatric age-range, the maturation of glomerular filtration rate (GFR) has been extensively studied by various groups (1,2,3,4,5,6,7), however, less is known about the functional in vivo development of other processes contributing to CLR (8) such as active tubular secretion (ATS), which is mediated through transporters in the kidneys.

In vivo transporter activity cannot be directly quantified but has to be derived from other measures. Recently, the ontogeny of individual renal transporters has been quantified by measuring transporter-specific protein expressions in postmortem kidney samples from children of different ages (9). However, there is limited information about how protein expression relates to in vivo transporter activity and whether this relationship remains constant with age. Alternatively, ontogeny of ATS has been quantified in vivo as net secretion of drugs with non-selective affinity for transporters. Net secretion aggregates the activity of all active secretion transporters involved in renal excretion and of reabsorption (3, 10). Since ontogeny patterns may differ between transporters, their relative contributions to CLR will also differ throughout the pediatric age-range, as drugs may have a broad spectrum in transporter affinity and can be transported by one or more transporters at once. Therefore, it would be of relevance to separately quantify the ontogeny of each renal transporter in vivo. Here we propose a new method to derive functional transporter ontogeny profiles in vivo.

Empirically, clinical pharmacokinetic (PK) data (i.e., concentration-time data) are analyzed using population PK (popPK) models. When analyzing pediatric PK data, the inter-individual variability in different parameters is driven by differences in underlying developing physiological processes. These differences are usually captured by a function that describes the relation between the individual deviations in parameter values from typical parameter values and a relatively small set of demographic variables that vary with age, i.e., covariate relationship. In pediatric physiology-based PK (PBPK) modeling, quantitative knowledge on developing physiology is included a priori in functions that describe changes in system-specific parameters. Subsequently, these models describe the interaction between drugs with certain physicochemical properties and this system. The parameters in a PBPK model can be derived from various data sources (e.g. in vitro experiments, clinical studies, etc.). Recently, combined popPK and PBPK approaches (which were referred to as popPBPK approaches, to not be confused with virtual PBPK populations) have been proposed to derive physiological measures for PBPK models that cannot be obtained through direct measures, by leveraging concentration-time data (11, 12). When selecting drugs that are predominantly eliminated by one main pathway, inferences can be made regarding system-specific parameters that are particular for that pathway.

In this study, the ontogeny of in vivo renal organic anion transporters 1 and 3 (OAT1,3) activity was characterized with this popPBPK approach. To this end, PK data obtained in critically ill children of different ages after the concomitant administration of clavulanic acid and amoxicillin was used. Each drug was assumed a probe for their specific elimination pathway, i.e., clavulanic acid for glomerular filtration (GF) and amoxicillin for a combination of GF and ATS through OAT1,3 (13, 14). With this methodology the ontogeny function of OAT1,3 could be estimated. Its predictive value was assessed by including the ontogeny function in a pediatric PBPK model to predict CLR of two other OAT1,3 substrates including cefazolin and piperacillin.

METHODS

Software

For the present analysis we used NONMEM v7.3 integrated with Pirana v2.9.9 for developing the model and R v3.5 integrated with RStudio for graphics and evaluation.

Quantifying the Ontogeny Function of OAT1,3 In Vivo

Clinical studies showed that the majority of an amoxicillin and clavulanic acid dose is recovered unchanged in urine (15,16,17,18) and in vitro evidence suggests that active secretion of amoxicillin is mainly mediated through OAT3 and to a lesser extent by OAT1 (13, 19). Different minor elimination routes may be involved, yet here we assume the clinical data to reflect the major elimination routes only. This implies the assumption that clavulanic acid clearance through other elimination routes than GF mature at the same rate as GF. For amoxicillin the extent of clearance through elimination routes other than active tubular secretion is assumed to be the same as for clavulanic acid and the difference in clearance between these two drugs is fully attributed to active tubular secretion through OAT1/3. Finally, even though the OAT1/3 transporter works in tandem with MRP4 efflux transporters, the contribution of MRP4 transporters to the CLR of amoxicillin and for piperacillin and cefazolin, mentioned later in the “methods” section, was excluded in the current example as the expression of this transporter was found to remain constant with age (9).

Individual post-hoc CLR values for clavulanic acid and amoxicillin in pediatric patients were obtained from a population PK model of De Cock et al. (20). In short, a simultaneous popPK analysis was performed for both drugs based on data obtained after the administration of a fixed dose ratio of 1:10 (clavulanic acid:amoxicillin) in 50 intensive care pediatric patients with ages between 1 month and 15 years (median age of 2.6 years) (20). The PK of clavulanic acid and amoxicillin were described by a two- and a three-compartment model, respectively, with inter-individual variability (IIV) on renal clearance (CLR) and central volume of distribution. The covariate analysis identified current weight as a statistically significant predictor for the IIV on both central volume of distribution and CLR, whereas vasopressor treatment and cystatin C were found to be statistically significant predictors only for the IIV on CLR (20).

In a sequential step, CLR was re-parameterized according to PBPK principles to reflect clearance through glomerular filtration (CLGF) and through active tubular secretion (CLATS) (Eqs. 1 and 2) (21). The PBPK-based model for CLR assumes a serial arrangement for GF and ATS, in which CLR of clavulanic acid was described by CLGF only (CLATS = 0), while CLR of amoxicillin was described by a combination of CLGF and CLATS.

In equation 1, GFR stands for glomerular filtration rate, fu for drug fraction unbound, QR for renal blood flow, CLsec,OAT1,3 for secretion clearance through OAT1,3, and BP for blood to plasma ratio. Equation 2 shows how CLsec,OAT1,3 is obtained by multiplying CLint,OAT1,3,in vivo that stands for OAT1,3-mediated in vivo intrinsic clearance in adults, with ontOAT1,3 that stands for the ontogeny function for OAT1,3, PTCPGK that stands for proximal tubule cells per gram kidney, and KW that stands for kidney weight in grams.

The adult PBPK-based model for CLR through a combination of GF and ATS (Eqs. 1 and 2) was extrapolated to the pediatric population. For this, published functions that describe the age-related changes of the system-specific parameters (i.e., GFR (2), renal blood flow (22), and kidney weight (22)) and of the drug-specific parameters impacted by changes in system-specific parameters (i.e., serum albumin concentrations (4) that influence the fraction unbound (23), and hematocrit levels that influence BP (22)) were inputted, as shown in Table S1. Values for fu (24) and BPamox .(25) as reported in adults were used (fu clav.acid = 0.75; fu amox = 0.82; BPamox.= 0.55). CLint,OAT1,3,in vivo reflects both the expression and activity of the OAT1,3 transporter in adults. Assuming PTCPGK to remain constant at adult values, this only leaves CLint,OAT1,3,in vivo and its ontogeny function (ontOAT1,3) to be estimated. This was done using the individual CLR values from the population model as dependent variables and deriving the system-specific PBPK parameters based on the individual patient characteristics for each patient.

Pediatric typical CLGF values were obtained using a published GFR maturation function developed for children with a normal renal function (2). However, when compared to normal CLGF values, CLR of both drugs as estimated with the population PK models, were found to be increased in the critically ill children included in the dataset of the current analysis (20). Hence, the PBPK-based re-parameterization of CLGF included a typical GF correction factor (θcorr) with IIV (ƞGFR) to account for this difference (equations 3).

As both amoxicillin and clavulanic acid were administered simultaneously to each child, from the data on clavulanic acid the GF correction factor and IIV on GFR for each pediatric patient was estimated. According to Eqs. 4 and 5, the difference between the individual values for CLR of amoxicillin and CLR of clavulanic acid were used to estimate CLATS, which was the basis for the estimation of the IIV on the in vivo CLsec,OAT1,3 value and subsequently the OAT1,3 ontogeny function (ontOAT1,3).

To quantify the ontogeny profile of CLint,OAT1,3,in vivo, different covariates (i.e. postnatal age, postmenstrual age, weight) were explored using sigmoid relationships (Eq. 6) or a simplification of this equation (i.e., an exponential equation). In Eq. 6, hill is the hill coefficient, which quantifies the steepness of the ontogeny slope and TM50 quantifies the age at which OAT1,3 reaches half of the adult value.

The statistical significance of including the ontOAT1,3 function in the equation for CLsec,OAT1,3,i to obtain CLR of amoxicillin was assessed according to the likelihood ratio test on the difference in objective function value. Under the assumption of a χ2 distribution, the objective function value of a model with one more degree of freedom had to be 3.84 points lower, with a corresponding p < 0.05 to indicate statistical significance (26). For graphical goodness-of-fit, a plot was made to check for prediction bias of the individual CLR values obtained either with the PBPK model or the individual post hoc values from the population PK model that served as the dependent variable in these fits. In addition, ETA (ƞGFR, ƞCLint,OAT1,3,invivo) vs. covariate plots (age, weight) are made to check for structural accuracy in PK parameters.

Predictive Properties of the OAT1,3 Ontogeny Function for New Substrates

To assess the predictive performance of the obtained OAT1,3 maturation function, the PBPK model that includes the estimated ontogeny function for OAT1,3 (Eqs. 1 and 2) was used for pediatric PBPK CLR predictions of piperacillin and cefazolin, two other substrates of the OAT1,3 transporter. PBPK predictions of CLR were compared to published typical pediatric CLR predictions by population PK models of the same drugs. Population models are considered the gold standard for deriving CLR values from observed concentration-time data and since neither the PBPK model nor the typical predictions by a population PK model take random inter-individual deviations in CLR into account, they can be directly compared.

To obtain the pediatric PBPK predictions for CLR, we collected literature values for fu, adult of 0.8 (27) and 0.31 (25) for piperacillin and cefazolin, respectively, and for BP adult of 0.55 for both drugs. CLint,OAT1,3,in vivo in Eq. 2 had to be derived for both drugs. This was done based on published in vitro activity data as measured in assays with OAT1,3 transfected cells (1.95 μl/min/mg protein (27) and 7.1 μl/min/mg protein (25) for piperacillin and cefazolin respectively). These values were further optimized based on the in vivo adult values for CLint,OAT1,3 using a retrospective IVIVE approach. More details on the retrospective IVIVE are provided in the supplemental materials.

The drug-specific CLint,OAT1,3, in vivo values obtained in the retrospective IVIVE step were used in Eqs. 1 and 2 of the renal PBPK model to obtain pediatric CLR predictions for cefazolin and piperacillin. Pediatric PBPK CLR predictions for piperacillin and cefazolin were made for typical individuals with the same demographic characteristics as the individual patients reported in the original publications describing the pediatric population PK models of these drugs (20, 28). This means that, for piperacillin, PBPK CLR values were estimated for 47 pediatric patients with ages between 2.5 months and 15 years (median age of 2.83 years). For cefazolin, the PBPK CLR values were estimated for 26 near-term neonates with gestational age higher than 35 weeks and postnatal age (PNA) between 1 and 30 days (median of 8 days). For this, the OAT3 ontogeny function obtained above for children of 1 month and older based on data from clavulanic acid and amoxicillin was extrapolated to the neonatal population.

Pediatric PBPK CLR predictions were visually and quantitatively compared to typical estimates obtained with published population PK models for these two OAT1,3 substrates. Precision was quantified as percentage root mean square prediction error (%RMSPE) (Eq. 7) and bias as percentage prediction error (%PE) (Eq. 8).

In both equations, CLR,PBPK are the CLR predictions obtained with the renal PBPK model in pediatrics and CLR,reference represents the CLR values for typical CLR predictions obtained with the published population PK models (28, 29). %RMSPE and %PE were calculated separately for piperacillin and cefazolin and reported overall as well as per age group. CLR,PBPK was considered to be accurately predicted if %RMSPE and %PE was within ±30%, reasonably accurately predicted between −30–−50% and 30–50% and inaccurate when %RMSPE and %PE were outside ±50%. Note that %RMSPE can only take positive values.

RESULTS

Quantifying the Ontogeny Function of OAT1,3

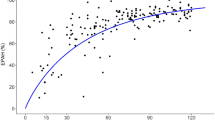

With the popPBPK approach, CLGF was separated from CLATS such that CLint,OAT1,3,in vivo and its ontogeny profile could be estimated in children as young as 1 month up to 15 years of age. Figure 1 shows the ontogeny profile of OAT1,3 as best described by a sigmoidal relationship based on PNA. CLint, OAT1,3, in vivo was estimated to be 15.8 ml/h/g kidney (RSE% of 5%) at 15 years with an IIV of 78.5%. This high IIV suggests large differences between individual values obtained for CLint, OAT1,3, in vivo. CLint, OAT1,3, in vivo was found to reach half of the adult capacity at a PNA of 27.3 weeks (RSE of 28%), which is around 7 months. The rapid ontogeny of OAT1,3 was captured by a hill exponent of 1.17 (%RSE of 36%). The estimated transporter ontogeny fractions range from 0.1 at 1 month and 1 at 15 years. The GF correction factor used to account for the increased CLR in critically ill children was estimated at 1.83 (RSE of 4%) with an IIV of 24.4%.

Ontogeny function for OAT1,3-mediated intrinsic clearance normalized by kidney weight (CLsec,OAT1,3– blue line) described by a sigmoidal function based on age and displayed throughout the studied pediatric age-range (1 month to 15 years), on a double-log scale. The orange dots represent the individual secretion clearance estimates normalized by kidney weight. See Eq. [5] for more details

The goodness-of-fit plots did not show any bias for CLR predictions obtained with CLR re-parameterized according to PBPK principles. Neither Fig. S1, which depicts popPBPK CLR predictions vs. the popPK CLR predictions, nor Fig. S2, which depicts the ƞGFR and ƞCLint,OAT1,3,in vivo vs. covariates (i.e., weight and age) show any bias. This suggests that the PBPK-based re-parameterization as CLGF (Eq. 3) can predict individual clavulanic acid CLR values accurately and that the reparameterization for CLGF together with CLATS (Eq. 4) can accurately predict the CLR of amoxicillin as excreted by GF and ATS through OAT1,3.

Figure 2 shows the total CLR for amoxicillin and the contribution of CLGF and CLATS to CLR for each individual. Total CLR increases almost 7-fold between neonates younger than 1 year and children of 10 years and older (median of 1.64 L/h and 12 L/h, respectively). The median contribution of ATS to amoxicillin CLR for the studied pediatric population was 22% (range: 4–40%). Even if variability in ATS contribution was high within groups of individuals with similar ages, the ATS contribution increased with age, on average, from 14% in children younger than 1 year to 18% in children of 1–2 years, 21% for children of 2–5 years, 24% for children 5–10 years, reaching 29% for children older than 10 years.

Contribution of clearance through glomerular filtration (CLGF – bottom blue boxes) and through active tubular secretion (CLATS – top orange boxes) to total renal clearance of amoxicillin (CLR – sum of blue and orange boxes) for each pediatric patient of the studied population sorted and grouped by age. The numbers in each box show the relative contribution of CLGF and CLATS to total CLR for each individual

Predictive Properties of the OAT1,3 Ontogeny Function

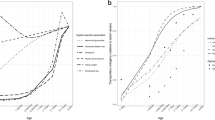

Figure 3 shows the pediatric CLR predictions for piperacillin and cefazolin obtained with the PBPK-based model and the identified OAT1,3 ontogeny function based on clavulanic acid and amoxicillin overlaid with the typical clearance estimates obtained with the published population PK models. The %RMSPE calculated between PBPK CLR and typical CLR predictions for piperacillin (Fig. 3a) over the entire age-range (2.5 months to 15 years) was 21.8% with a %PE interval between −33.2% and 25.4%. When stratified per age groups (i.e., younger than 1 year, 1–2 years, 2–5 years, 5–10 years and older than 10 years) %RMSPE is generally higher for children under 5 years (23.3, 22.2, and 27.4% vs. 14.9, 18.8%). For neonates (Fig. 3b), the %RMSPE calculated between PBPK CLR and typical CLR predictions for cefazolin was 22.2% with %PE interval between −34.4 and 46%.

For both pediatric populations the PBPK-based CLR predictions can be considered reasonably accurate with %RMPE < 30% and %PE within ±50%. For piperacillin, the PBPK-based CLR predictions tend towards overprediction (Fig. 3a), with all %PE values below 0%, although percentage deviations were acceptable [%PE between −13.3 and −28.8%] for children older than 1 year. For cefazolin in neonates, predictions are reasonably accurate (Fig. 3b), with PBPK-based CLR predictions tending towards underprediction [%PE between 18.1 and 46%] for children older than 10 days.

DISCUSSION

With a combined population PK with PBPK approach, referred to as popPBPK, we estimated the functional in vivo ontogeny profile for OAT1,3, a parameter that cannot be obtained through direct measurements, down to the age of 1 month. Under the assumption that clavulanic acid is entirely eliminated through GF and amoxicillin through GF and ATS through OAT1,3, we used clinical PK data of children that received both drugs at the time to define a maturation function for ATS through OAT1,3. Using a population PK approach, we derived the individual CLR values for both drugs that served as dependent variable for the popPBPK approach. CLR was re-parameterized according to PBPK principles to take advantage of existing information about drug- and system-specific properties while estimating the ontogeny of OAT1,3 in vivo and the variability on GFR and on OAT1,3-mediated intrinsic clearance in vivo (CLint,OAT1,3, in vivo).

Our group recently developed a PBPK simulation framework for investigating the impact of ontogeny of renal secretion transporters on CLR by predicting pediatric CLR for hypothetical drugs with an array of drug properties (30). By looking at the difference between PBPK CLR predictions with or without inclusion of the ontogeny function, probe drugs for quantifying the ontogeny of transporters were identified. According to the findings with this framework, amoxicillin, which has an estimated CLint,OAT1,3, in vivo of 4.4 μl/min/mg protein and a fu of 0.82 (31), has the potential of serving as a probe to quantify OAT1,3 ontogeny. Furthermore, the clinical data available for probe drugs for GF and a combination of GF and ATS (clavulanic acid and amoxicillin, respectively) administrated to the same individuals was paramount to separate between these two processes.

OAT1,3 ontogeny for the OAT1,3-mediated intrinsic clearance is steep in the first year of life, attaining half of the adult value around 7 months of age. This estimated ontogeny function was included in the pediatric PBPK-based model for CLR through GF and ATS. Even though the functional in vivo OAT1,3 ontogeny profile was derived from clinical data obtained in critically ill patients without renal disfunction, it predicted the CLR for other drugs that are substrates for OAT1,3 reasonably accurate, as compared to popPK CLR predictions for these drugs. Assuming clearance to be only mediated by GF and ATS, for piperacillin the PBPK CLR predictions over an age-range of 2.5 months to 15 years lead to a %RMSPE of 21.8% [%PE: −33.2–25.4%] with a trend towards over-prediction for children older than 1 year. For cefazolin, extrapolation of CLR predictions to near term neonates with ages between 1- and 30-days lead to a %RMSPE of 22.2% [%PE: −34.4%–46%.], with a trend towards under-prediction for children older than 10 days.

Previously, Hayton et al. used para-aminohippurate to derive an ontogeny profile of undifferentiated active renal secretion in vivo, concluding that 50% maturation is achieved around 1 year of age (3), which is comparable with our findings. Recently, more insight into differentiated ontogeny profiles of individual renal transporters have been quantified based on direct measurements of the expression of transporter-specific proteins in kidney samples taken postmortem from children of various ages, as described in detail by Cheung et al. (9). This group characterized the ontogeny of OAT1,3 as a sigmoidal function based on PNA in weeks with children reaching half of the adult values around 8 months of age (TM50 = 30.7 weeks [95% CI: 16.64–50.97]) and the steepness of the ontogeny slope given by a hill coefficient of 0.51 (95% CI: 0.35–0.71). While our findings align with Cheung et al. regarding the age at which half of the adult level is reached, which was estimated to be around 7 months with our function, we found a steeper ontogeny for OAT1,3, as shown by a 2-fold higher estimated hill coefficient. The impact of these differences on the ontogeny profiles is illustrated in Fig. 4. This figure shows relatively similar OAT1,3 ontogeny found by both methods at ages above the TM50 values, but for younger ages the function quantified in our work shows lower ontogeny values. Given the low number of observed values at these younger ages in both analyses, the uncertainty around the ontogeny below 7 months of age is high for both analyses. More data are required to establish the accuracy of the estimated in vivo functional ontogeny profile in the first year of life.

Ontogeny functions for OAT(1),3-mediated intrinsic clearance normalized by kidney weight (CLint,OAT1,3,in vivo) throughout the studied pediatric age-range (1 month to 15 years). The solid line shows the sigmoidal function estimated in the current analysis whereas the dashed line shows the ontogeny function for OAT1 as published by Cheung (9). The orange dots represent the individual secretion clearance estimates normalized by kidney weight derived from amoxicillin CLR values obtained with the current analysis. See Eq. [5] for more details

Although drugs may be predominantly eliminated by a particular pathway, they are rarely exclusively cleared through a single, well-defined pathway. However, despite the fact that the estimated functional OAT1,3 ontogeny profile may be impacted by minor elimination pathways contributing to the clearance of clavulanic acid and amoxicillin, this function could be used to obtain accurate pediatric PBPK-based CLR predictions for two other drugs that are predominantly, though not exclusively, eliminated through GF and OAT1,3-mediated ATS, namely piperacillin and cefazolin. Despite small trends towards over and under-prediction respectively, CLR predictions for piperacillin and cefazolin were reasonably accurate with %RMSPE of 21.8 and 22.2%, which is well below the 2-fold error, which is the generally accepted criterion for accuracy of PBPK predictions. The tendency towards over-prediction of pediatric PBPK CLR for piperacillin could be explained by other processes involved in renal elimination that are not accounted for in the PBPK model. It could for instance be that there is passive or active reuptake of these drugs in the kidneys. Alternatively, the authors of the popPK model that served as the reference values, reported a (temporary) impairment of the renal maturation function (29) which could explain the lower CLR values obtained with the popPK model as compared to the PBPK CLR predictions, the latter of which does not take (potential) renal impairment into account. A second drug, cefazolin, was used to assess the accuracy of this function for extrapolations to term newborns below 1 month of age. Remarkably, despite a small trend towards under-prediction of CLR values for cefazolin in part of the newborns, all predictions can still be considered accurate.

The methodology proposed here is the first to enable the assessment of functional in vivo activity, rather than mRNA or transporter expression or ex vivo activity. As such it cannot only augment the currently available methods to study renal transporter maturation throughout the pediatric age-range, but can also offer a valuable new dimension to this research. Essential in our approach is the requirement of data on two probe drugs that are predominantly excreted by specifically GFR and a combination of GFR and ATS through a specific transporter. As studies in healthy pediatric populations are not allowed, the two probe drugs would have to be regularly prescribed for therapeutic purposes in children across the entire age-range. Furthermore, practical and ethical constraints may require assumptions to be made in the implementation of this method. For instance, in the example used here to illustrate our approach, we assumed exclusive elimination of our probe drugs through GF and OAT1,3-mediated ATS, as ethical and practical constraints prevent urine collection over prolonged durations and thereby the formal assessment of the contribution of renal excretion to overall drug elimination. This may have impacted the accuracy of the obtained ontogeny function, but it does not impact our proposed methodology conceptually. If information on minor elimination routes would become available, this could be included in the PBPK model to further refine the estimated ontogeny function.

CONCLUSION

The ontogeny of functional in vivo OAT1,3 activity was derived by using a combined population PK and PBPK modeling approach. This popPBPK approach leverages the knowledge on underlying physiological processes included in PBPK models and information carried by individual PK parameters as quantified with a population approach, to derive parameters that cannot be measured in vivo. With this methodology we derived the renal OAT1,3 transporter ontogeny in vivo. This ontogeny function was included in the pediatric PBPK-based model CLR for two other OAT1,3 substrates and on average predicted CLR throughout the entire pediatric age-range accurately. This methodology could be applied to other transporters substrates to characterize the in vivo ontogeny of the remaining renal transporters to further increase our understanding on renal development and increase the accuracy in predicting pediatric CLR.

References

Rhodin MM, Anderson BJ, Peters AM, Coulthard MG, Wilkins B, Cole M, et al. Human renal function maturation: a quantitative description using weight and postmenstrual age. Pediatr Nephrol. 2009;24(1):67–76.

Salem F, Johnson TN, Abduljalil K, Tucker GT, Rostami-Hodjegan A. A re-evaluation and validation of ontogeny functions for cytochrome P450 1A2 and 3A4 based on in vivo data. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2014;53(7):625–36.

Hayton WL. Maturation and growth of renal function: dosing renally cleared drugs in children. AAPS PharmSci. 2000;2(1):E3.

Johnson TN, Rostami-Hodjegan A, Tucker GT. Prediction of the clearance of eleven drugs and associated variability in neonates, infants and children. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2006;45(9):931–56.

Mahmood I. Dosing in children: a critical review of the pharmacokinetic allometric scaling and modelling approaches in paediatric drug development and clinical settings. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2014;53(4):327–46.

De Cock RFW, et al. Simultaneous pharmacokinetic modeling of gentamicin, tobramycin and vancomycin clearance from neonates to adults: towards a semi-physiological function for maturation in glomerular filtration. Pharm Res. 2014;31(10):2643–54.

Bueters R, Bael A, Gasthuys E, Chen C, Schreuder MF, Frazier KS. Ontogeny and cross-species comparison of pathways involved in drug absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion in neonates (review): kidney. Drug Metab Dispos. 2020;48(5):353–67.

Brouwer KLR, Aleksunes LM, Brandys B, Giacoia GP, Knipp G, Lukacova V, et al. Human ontogeny of drug transporters: review and recommendations of the Pediatric Transporter Working Group. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2015;98(3):266–87.

Cheung KWK, Groen BD, Spaans E, Borselen MD, Bruijn ACJM, Simons-Oosterhuis Y, et al. A comprehensive analysis of ontogeny of renal drug transporters: mRNA analyses, quantitative proteomics, and localization. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2019;106:1083–92.

Rubin MI, Bruck E, Rapoport M, Snively M, McKay H, Baumler A. Maturation of renal function in childhood: clearance studies. J Clin Invest. 1949;28(5 Pt 2):1144–62.

Tsamandouras N, Rostami-Hodjegan A, Aarons L. Combining the “bottom up” and “top down” approaches in pharmacokinetic modelling: fitting PBPK models to observed clinical data. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2015;79(1):48–55.

Calvier EAM, et al. Can population modelling principles be used to identify key PBPK parameters for paediatric clearance predictions? An innovative application of optimal design theory. Pharm Res. 2018;35:209.

Parvez MM, et al. Comprehensive substrate characterization of 22 antituberculosis drugs for multiple solute carrier (SLC) uptake transporters in vitro. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2018;62(9):1–12.

Horber FF, Frey FJ, Descoeudres C, Murray AT, Reubi FC. Differential effect of impaired renal function on the kinetics of clavulanic acid and amoxicillin. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1986;29(4):614–9.

Bolton GC, Allen GD, Davies BE, Filer CW, Jeffery DJ. The disposition of clavulanic acid in man. Xenobiotica. 1986;16:853–63.

Arancibia A, Guttmann J, Gonzalez G, Gonzalez C. Absorption and disposition kinetics of amoxicillin in normal human subjects. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1980;17:199–202.

RxList database. https://www.rxlist.com/amoxicillin-drug.htm#clinpharm.

EMA. AUGMENTIN® (amoxicillin/clavulanate potassium) https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/referral/augmentin-article-30-annex-iii_en.pdf.

Varma MV, el-Kattan AF, Feng B, Steyn SJ, Maurer TS, Scott DO, et al. Extended Clearance Classification System (ECCS) informed approach for evaluating investigational drugs as substrates of drug transporters. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2017;102(1):33–6.

De Cock PAJG, et al. Augmented renal clearance implies a need for increased amoxicillin-clavulanic acid dosing in critically ill children. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2015;59(11):7027–35.

Rowland Yeo K, Aarabi M, Jamei M, Rostami-Hodjegan A. Modeling and predicting drug pharmacokinetics in patients with renal impairment. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol. 2011;4(2):261–74.

Simcyp (a Certara Company). Simcyp v18. 2018.

McNamara PJ, Alcorn J. Protein binding predictions in infants. AAPS PharmSci. 2002;4(1):E4.

FDA. AUGMENTIN® (amoxicillin/clavulanate potassium): Prescribing information https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2009/050755s014lbl.pdf.

Mathialagan S, Piotrowski MA, Tess DA, Feng B, Litchfield J, Varma MV. Quantitative prediction of human renal clearance and drug-drug interactions of organic anion transporter substrates using in vitro transport data: a relative activity factor approach. Drug Metab Dispos. 2017;45(4):409–17.

Nguyen THT, Mouksassi MS, Holford N, al-Huniti N, Freedman I, Hooker AC, et al. Model evaluation of continuous data pharmacometric models: metrics and graphics. CPT Pharmacometrics Syst Pharmacol. 2017;6(2):87–109.

Wen S, et al. OAT1 and OAT3 also mediate the drug-drug interaction between piperacillin and tazobactam. Int J Pharm. 2018;537(1-2):172–82.

De Cock RFW, et al. Population pharmacokinetic modelling of total and unbound cefazolin plasma concentrations as a guide for dosing in preterm and term neonates. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2014;69(5):1330–8.

De Cock PAJG, et al. Dose optimization of piperacillin/tazobactam in critically ill children. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2017;72(7):2002–11.

Cristea S, et al. The influence of drug properties and ontogeny of transporters on pediatric renal clearance through glomerular filtration and active secretion: a simulation-based study. AAPS J. 2020;22(4):1–10.

FDA. AUGMENTIN® (amoxicillin/clavulanate potassium) Powder for Oral Suspension and Chewable Tablets 2008. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2008/050575s037550597s044050725s025050726s019lbl.pdf.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

ESM 1

(DOCX 511 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Cristea, S., Krekels, E.H.J., Allegaert, K. et al. Estimation of Ontogeny Functions for Renal Transporters Using a Combined Population Pharmacokinetic and Physiology-Based Pharmacokinetic Approach: Application to OAT1,3. AAPS J 23, 65 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1208/s12248-021-00595-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1208/s12248-021-00595-9