Abstract

The purpose of this study was to investigate if model-based post-processing of common diagnostics can be used as a diagnostic tool to quantitatively identify model misspecifications and rectifying actions. The main investigated diagnostic is conditional weighted residuals (CWRES). We have selected to showcase this principle with residual unexplained variability (RUV) models, where the new diagnostic tool is used to scan extended RUV models and assess in a fast and robust way whether, and what, extensions are expected to provide a superior description of data. The extended RUV models evaluated were autocorrelated errors, dynamic transform both sides, inter-individual variability on RUV, power error model, t-distributed errors, and time-varying error magnitude. The agreement in improvement in goodness-of-fit between implementing these extended RUV models on the original model and implementing these extended RUV models on CWRES was evaluated in real and simulated data examples. Real data exercise was applied to three other diagnostics: conditional weighted residuals with interaction (CWRESI), individual weighted residuals (IWRES), and normalized prediction distribution errors (NPDE). CWRES modeling typically predicted (i) the nature of model misspecifications, (ii) the magnitude of the expected improvement in fit in terms of difference in objective function value (ΔOFV), and (iii) the parameter estimates associated with the model extension. Alternative metrics (CWRESI, IWRES, and NPDE) also provided valuable information, but with a lower predictive performance of ΔOFV compared to CWRES. This method is a fast and easily automated diagnostic tool for RUV model development/evaluation process; it is already implemented in the software package PsN.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

INTRODUCTION

Nonlinear mixed effects (NLME) models are widely used to describe clinical data in drug development for learning about the underlying physiological system, confirming drug effects, simulating different scenarios for dose selection, and decision making (1). These models incorporate mathematical description of structural components (fixed effects) and stochastic components (random effects). Random effects account for multiple sources of variability: inter-individual variability (IIV), inter-occasion variability (IOV), and residual unexplained variability (RUV). RUV incorporates intra-individual variability, inaccuracies in dosing and sampling history, measurement errors, and model misspecification. It is assumed that the RUV model allows the transformation of a normal, independent, and identically distributed random variable to capture the full complexity of any heteroscedasticity, non-normality, and dependence in the RUV between the model and data. It has been shown that maximum likelihood estimation of model parameters with misspecified RUV model results in biased parameter estimates (2), and conclusions regarding covariate inclusion or parameter uncertainty based on such fit may not be correct (3,4). Thus, selection of an appropriate RUV model is important for maximum likelihood estimation, real-life-like simulations, better utilization of data, and subsequent model-informed decisions.

Extended RUV models have been developed to various RUV characteristics. An autoregressive (AR1) error model has been used to describe serially correlated residuals which may occur with rich data in particular (2,5). One example of this was a case study of glucose tolerance test, where AR1 errors provided a better description of the data (6). A dynamic transform both sides (dTBS) approach account for skewness and scedasticity of the residuals by estimating a shape parameter (λ) and a power term (ζ) using a Box-Cox transform to both data and model predictions (7,8). Inter-individual variability IIV in the magnitude of RUV relaxes the assumption that all subjects display a common residual error variance (9). A power error model accounts for residual error scedasticity dependent on model predictions and as such offers an alternative to the commonly used additive plus proportional RUV model. A Student’s t-distributed error model allows for symmetric heavy tails in residual distribution and thus introduces outlier robustness in the model (9). Time-varying error magnitude has been observed for example for oral pharmacokinetic profiles with higher error magnitude during the absorption phase (2). A simple implementation of such a RUV extension is through a step function where the error magnitude changes at a certain time (after dose).

Despite the availability of these extended RUV models, they are seldom tested. A factor limiting these extended RUV models from being routinely checked is the absence of a fast, easy-to-use and accurate diagnostic tool, as implementing these extended RUV models one by one can be time-consuming and computationally intensive. This gets even more complicated in simultaneous modeling of multi-dependent variables, where exploring these extended RUV models for each of the dependent variables will result in large number of combinations to be tested. The recommended diagnostic tools for assessing RUV models are limited to plots of residuals versus time/model prediction (10,11). Such graphical diagnostic provide guidance only for selection among the standard RUV models: additive, proportional, or combined error model. Extended RUV models are mostly implemented based on subjective decision (e.g., log transformation of both sides), implementation facility (e.g., numerical instability of parameter estimation), or expected features (e.g., autocorrelation with rich frequent sampling schedule). To avoid this limited and case-dependent RUV modeling, here, we investigate if post-processing of common model-based diagnostics can provide additional advantages. We propose a new diagnostic tool, based on standard output such as conditional weighted residuals (CWRES), which scan these extended RUV models for their ability to improve the description of data, without re-estimating the original NLME model.

METHODS

We choose to illustrate the diagnostic procedure using CWRES which are theoretically expected to be normally distributed with mean 0 and variance 1 for a correct NLME model (12). CWRES are computed based on individual’s empirical Bayes estimates regardless what estimation method is used (Eq. 1–5):

where \( {\overset{\rightharpoonup }{y}}_i \) is the vector of observations for the ith individual, f denotes individual model predictions,\( \overset{\rightharpoonup }{\theta } \) is the vector of population fixed effects, \( {\overset{\rightharpoonup }{\eta}}_i \) is vector of random unexplained individual deviation from the population fixed effects, h is RUV model, \( {\overset{\rightharpoonup }{\varepsilon}}_i \) is the vector of residual errors, \( E\left({\overset{\rightharpoonup }{y}}_i\right) \) is the expectation of the marginal density of the data given the model, 𝜂\( {\widehat{\eta}}_i \) is vector of empirical Bayes estimates, and \( \mathrm{COV}\left({\overset{\rightharpoonup }{y}}_i\right) \) is the covariance of the marginal density of the data given the model. Both random effects, \( {\overset{\rightharpoonup }{\eta}}_i \) and\( {\overset{\rightharpoonup }{\varepsilon}}_i \) are assumed to follow normal distribution with mean 0 and covariance matrix Ω and Σ, respectively. Hence, CWRES are directly linked to the objective function used in FOCE estimation method (12).

CWRES Base Model

As a substitute for assessing extended RUV models on the original data, the extended models were applied to a CWRES distribution. Thus, CWRES calculated from the original NLME model execution were treated as the dependent variable (DV) and modeled first by a linear base model to estimate CWRES distribution’s mean and variance as follow:

where \( {\overset{\rightharpoonup }{y}}_i \) is a vector of CWRES data from individual i, Θ1 is the population mean of CWRES, η1i is a univariate random variable describing the unexplained deviation of individual i from Θ1, and η1i is assumed to follow a normal distribution of a mean 0 with variance ω2. \( {\overset{\rightharpoonup }{\varepsilon}}_{1i} \) is a univariate random variable describing residual unexplained variability of individual i; it is assumed to be independent identically normally distributed with a mean 0 and variance σ2. When the original NLME model is describing the data adequately, the expected mean of CWRES Θ1 is 0, the expected value of ω2 is 0, and the expected value of σ2 is 1. This base model (Eq. 6) was then extended with the different RUV models (Supplementary material) as follow:

Autocorrelated Errors

The CWRES calculated from the original NLME model were modeled using an autoregressive error model AR1 as

where ɛij is the residual error for individual i at time j, ɛik is the residual error for individual i at time point k, and t1/2 is half-life governing the duration of the correlation. ΔOFVCWRES_AR1 was calculated as the difference between base model objective function value OFVCWRES_Base and AR1 error model objective function value OFVCWRES_AR1.

Dynamic Transform both Sides

The individual predictions (IPREDs) calculated from the original model were used for the dTBS implementation. The dTBS model uses a Box-Cox transformation and as such requires the underlying variable to be positive; this is an issue as CWRES data includes negative observations. Thus, two models were needed to apply dTBS on CWRES data: (1) new base model instead of (Eq. 6) called CWRES dTBS base model and (2) CWRES dTBS model.

In CWRES dTBS base model, CWRES data was first exponentiated (Eq. 8) then a dTBS model (Eq. 9) with both shape parameter λ and power term ζ fixed to zero (log-normal transformation with homoscedastic variance) was fitted to the exponentiated CWRES data to calculate OFVCWRES_dTBS_base.

In CWRES dTBS model, a dTBS model (Eq. 10) was fitted to the exponentiated CWRES data with estimating both λ and ζ, to calculate OFVCWRES_dTBS:

where an estimate of λ = 0 means CWRES data was normally distributed before being exponentiated, λ > 0 means CWRES data was left skewed before being exponentiated, and λ < 0 means CWRES data was right skewed before being exponentiated.

ΔOFVCWRES_dTBS was calculated as the difference between dTBS base model objective function value OFVCWRES_dTBS_base and dTBS model objective function value OFVCWRES_dTBS.

Inter-Individual Variability on RUV

The CWRES data outputted from the original model execution was modeled as

where η2i is random deviation of individual i from \( {\overset{\rightharpoonup }{\varepsilon}}_{1i} \), thus allowing different individuals to have different RUV magnitude. ΔOFVCWRES_IIV was calculated as the difference between base model objective function value OFVCWRES_Base and IIV on RUV model objective function value OFVCWRES_IIV.

Power Model

The individual predictions IPRED calculated on normal scale from the original model execution were used to scale individual residual error \( {\overset{\rightharpoonup }{\varepsilon}}_i \) where CWRES was modeled as

where ζ is the power exponent determining the dependence of \( {\overset{\rightharpoonup }{\varepsilon}}_i \) on model prediction. IPRED should include only positive values for successful implementation. If for instance IPRED included negative predictions because of log transformation, they were exponentiated back to normal scale. ΔOFVCWRES_power was calculated as the difference between OFVCWRES_Base and power error model objective function value OFVCWRES_power.

t-Distribution Error Model

The Laplacian method with user-defined likelihood had to be used to apply a t-distributed residual error. The conditional likelihood L of CWRES data was defined in the control file for a Laplace base model (Eq. 13) and a t-distributed error model (Eq. 14):

where σ2 is the variance of the data, IWRES is the individual weighted residuals, Γ is the gamma function, and υ is the degrees of freedom, which is the additionally estimated parameter when extending the RUV model to a t-distributed error. ΔOFVCWRES_t − dist was calculated as the difference between Laplace base model objective function value OFVCWRES_Laplace_base and t-distribution error model objective function value OFVCWRES_t − dist.

Time-Varying Error

Time, or time after dose, could be used as predictor of residual error magnitude (2), where cutoff time points for the change in variance of ɛi are selected based on data density to cut the data into N equal-size groups. CWRES were modeled as

where ɛ2i is the residual error after the cutoff time point X. The number of cutoff time points is subjective; here, we used three cutoff time points to cut the data into four equal-size groups, each with a separate error magnitude. ΔOFVCWRES_time was calculated as the difference between OFVCWRES_Base and the time-varying error model objective function value OFVCWRES_time.

Evaluations

The agreement in improvement of fit (ΔOFV) between implementing these extended RUV models on the original NLME model (ΔOFVOriginal; conventional analysis) and implementing them on CWRES data (ΔOFVCWRES) was evaluated in both simulated (n = 7) and real (n = 16) data examples as described below. For each data set and RUV model considered, there were thus two models evaluated for the original data (the original model and one with RUV model extension) and two models for the CWRES obtained from the original NLME model (the base CWRES model and the extended RUV model). In addition to CWRES, real data exercise was applied to three other diagnostics: conditional weighted residuals with interaction (CWRESI), individual weighted residuals (IWRES) and normalized prediction distribution errors (NPDE). CWRESI considers the interaction between intra- and inter-individual variability as in proportional error model. IWRES are the differences between the observations and IPRED weighted by the expected standard deviation of the residual variability (σ) only.

NPDEs are calculated by applying the inverse function of the normal cumulative density function to the decorrelated prediction discrepancies, and so it is normally distributed by construction without any approximations (13).

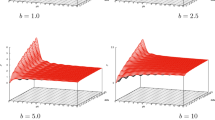

Simulations

Stochastic simulations and estimation (SSEs) were performed to investigate the ability of CWRES modeling to identify correctly the true extended RUV model in different scenarios, as well as investigating type I error rates of the likelihood ratio test employed, with null hypothesis being the absence of RUV misspecification The base simulation model was a one-compartment disposition model with first-order absorption, linear elimination, and proportional RUV model. Parameters assigned with inter-individual variability were absorption rate constant, clearance, and volume of distribution, with a correlation between the last two parameters. This base model was extended with the investigated RUV models to produce six additional models. The base model was used to simulate 200 datasets, while each of the extended RUV models was used to simulate 100 datasets; each dataset was estimated with the seven models to calculate mean ΔOFVOriginal for each extended RUV model. CWRES calculated from the estimated base models and modeled as described previously to calculate mean ΔOFVCWRES for each extended RUV model (Fig. 1). The values of parameters governing each of the extended RUV models when simulating were chosen to produce a ΔOFVOriginal of up to 100 between the base model and the true extended RUV model.

Schematic presentation of simulation setup. The base model was used to simulate 200 data sets, while each of the extended RUV models was used to simulate 100 datasets, and each dataset was estimated with the seven models to calculate mean ΔOFVOriginal for each extended RUV model. CWRES outputted from the base model fitting to the simulated data in each of the different scenarios were treated as dependent variables and modeled with same RUV extensions to calculate mean ΔOFVCWRES for each extended RUV model. Note that different base models were needed for dTBS and t-distribution error models

Real Data Examples

Models varied in complexity, amount of available data, and residual error components (Table I). Four examples modeled more than one dependent variable simultaneously. Data was log-transformed in nine examples. Two examples already included IIV on RUV model and this was then considered the base RUV model. All examples were developed using the FOCE method, and the interaction option was added in relevant RUV extended models.

Software

NONMEM version 7.3 (ICON Development Solutions, Hanover, MD, USA) (29) was used for the analysis with help of PsN (30), and graphs were generated in R (31).

RESULTS

Simulated Data Examples

CWRES modeling identified the same (correct) RUV model as the conventional analysis as shown in Fig. 2. The highest ΔOFVCWRES signaled the correct RUV extension model used in the simulation for AR1, dTBS, IIV, t-distribution, and time-varying RUV error models, e.g., ΔOFVCWRES_AR1was the highest drop between all CWRES models (red bars) when simulating with AR1 error model. Note that the Power and dTBS models are nested and the results reflected this. Since when simulating with power error model only correction for residual scedasticity was needed, both ΔOFVCWRES_power and ΔOFVCWRES_dTBS were of equal magnitude, − 20 and − 22, respectively, so it is clear that dTBS model is not providing any additional advantages over power error model which should be selected as the correct RUV model extension. Type I error rates with CWRES were 1.5, 1, 2, 5.5, 3, and 8.5% for AR1, dTBS, IIV, power, t-distribution, and time-varying RUV models, respectively, taking into account the number of estimated parameters. When simulating with the base model, none of the investigated extension showed an improvement either by CWRES modeling or conventional analysis.

Plot of mean ΔOFV vs extended RUV models show the agreement between mean ΔOFVOriginal (gray) and mean ΔOFVCWRES (red) among all seven scenarios of simulations. Abbreviations: AR1 autocorrelated errors, dTBS dynamic transform both sides, IIV inter-individual variability on RUV, Power power error model, t-dist t-distribution error model, TV time-varying error model

The improvement in goodness-of-fit ΔOFV when applying an extension was in general of similar magnitude whether based on ΔOFVCWRES or ΔOFVOriginal. However, if the method worked perfectly, ΔOFVCWRES would equal exactly ΔOFVOriginal which is not the case especially for AR1 simulation scenario, where ΔOFVCWRES were − 34, while ΔOFVOriginalwas − 100. The parameters governing these extended RUV models showed a good concordance between their estimates from CWRES and conventional analysis, with a correlation coefficient of 0.93 across all RUV extensions except for dTBS as they are on different scale.

Real Data Examples

At least one of the investigated RUV extensions resulted into a significant ΔOFVOriginal in all examples except for Daunorubicin and Digoxin PD models. When significant, the improvement was substantial with ΔOFVOriginal ranging from − 2019 for Gastric emptying with autocorrelated error to − 4 for r-hFSH PK with IIV on RUV, with a median ΔOFVOriginal of − 71 across models with significant improvement. Similar to the conventional analysis, a significant ΔOFVCWRES were found in all examples except for Daunorubicin and Digoxin PD models. The real data examples further supported the good agreement between the true misspecification in error model and what was identified by modeling of CWRES as CWRES modeling identified the most important RUV extension similar to the conventional analysis (Fig. 3). Exceptions were the two models Ethambutol PK and Disufenton sodium, where the order of the 1st (t-distribution) and 2nd most important extensions (IIV on RUV) were reversed. CWRES modeling identified the same RUV extensions to be significant improvements as conventional analysis except for t-distributed error model with Asenapine PD. The ΔOFVOriginal and ΔOFVCWRES displayed a correlation coefficient of 0.88 across all models and a median ratio \( \frac{{\Delta \mathrm{OFV}}_{CWRES}}{{\Delta \mathrm{OFV}}_{Original}} \) of 0.77 among models with significant improvement. It is not surprising that this ratio is below one as when extending the original model, there is always the potential for larger improvement in fit than CWRES as many parameters are re-estimated under the new RUV model.

The evaluation of the other diagnostics CWRESI, IWRES, and NPDE with real data examples is shown in Fig. 4, where CWRES outperformed other diagnostics in predicting ΔOFVOriginal. The root mean-squared errors (RMSE) of ΔOFVCWRES were lower than RMSE of other ΔOFVdiagnostics and so they are reported as relative to RMSE of ΔOFVCWRES as shown in Table II, where RMSE measures the differences between ΔOFVdiagnostics and the actually observed ΔOFVOriginal.

DISCUSSION

A new diagnostic tool for post-processing of CWRES was successfully developed and evaluated. CWRES modeling evaluate extended RUV models and assess in a robust and extremely fast way whether extensions are needed to implement. The method accurately identified the correct type of RUV model misspecifications as well as the expected improvement in fit in terms of ΔOFV and the expected parameters of the extended RUV model, similar to conventional analysis. This method typically does not suffer from local minima problems or other estimation-related issues because CWRES models are simple and quick to run with known expected distribution as shown by the agreement between ΔOFVOriginal and ΔOFVCWRES. In no case was modifications of initial estimates needed for the CWRES models applied here.

Simulation results elucidated the ability of different extensions to describe each other and to produce similar improvement in fit. The t-distributed error model allows the incorporation of outlier robustness into the model while IIV on RUV allows individuals to have different RUV magnitude; thus, both extensions can describe outliers and produce similar model fits. This behavior was shown when simulating with IIV on RUV; t-distributed error model was the 2nd most important RUV extension. This behavior also might explain the inflated ΔOFVCWRES_IIV when t-distributed error model was the most important improvement in both simulated and real data examples, and the reversed order of most important RUV extensions for Ethambutol PK and Disfenton sodium.

Both dTBS and Power error model can account for scedasticity; however, only dTBS can correct for both scedasticity and skewness; thus, on simulating from power error model, both extensions had similar ΔOFVCWRES but not when simulating from dTBS; a profound real data example of this was Pefloxacin where ΔOFVOriginal_power(ΔOFVCWRES_power) was − 65 (− 50) and ΔOFVOriginal_dTBS (ΔOFVCWRES_dTBS) was − 70 (− 50) as correction for scedasticity was only in need. On the other hand, a correction for both scedasticity and skewness was needed for Moxonodine PK where ΔOFVOriginal_power(ΔOFVCWRES_power) was − 60 (− 48) and ΔOFVOriginal_dTBS (ΔOFVCWRES_dTBS) was − 243 (− 87).

As mentioned in our results, ΔOFVOriginal is expected to be larger than ΔOFVCWRES, as it is more flexible with more parameters to estimate; this difference between the ΔOFVs was most pronounced with the dTBS approach as shown by most results being in the top left triangle in Fig. 3 when correction for scedasticity and skewness resulted in different non-residual error parameter estimates, for example in Disufenton sodium PK:ΔOFVOriginal_dTBS (ΔOFVCWRES_dTBS) was − 116 (− 80) as implementing dTBS led to a relative change of 126, 12, 30, 10, 6, 16, and 15% in estimates of THETAs’ from 1 to 7 respectively.

One interesting aspect is in case of multiple dependent variables, using CWRES modeling identified accurately which dependent variable needed further improvement which decrease the risk of model over parameterization. For example, the Gastric emptying PK model had four dependent variables; by conventional analysis, only the total ΔOFVOriginal_dTBS (− 433) is obtained but this does not provide information about for which dependent variable an extended RUV model is dominating the improvement in fit. On the other hand, by CWRES modeling, four separate ΔOFVCWRES_dTBS, one for each dependent variable, are obtained and only the 2nd (ΔOFVCWRES_dTBS = − 207) and 4th (ΔOFVCWRES_dTBS = − 139) dependent variables could be identified as important to transform in the original model.

Other common diagnostics CWRESI, IWRES, and NPDE are available for evaluation of model goodness of fit. Similar to CWRES, these diagnostics should be normally distributed when the model adequately describe the data, except for CWRESI because of the interaction between \( {\overset{\rightharpoonup }{\eta}}_i \) and\( {\overset{\rightharpoonup }{\varepsilon}}_i \). It had been concluded previously that IWRES perform poorly with increasing model non-linearity, leading to biased parameter estimates and misguided model development (12), and that CWRES and NPDE give the best diagnostics in different situations even when there was interaction in the model (32); our results support these conclusions with a further favor of CWRES over NPDE as shown in Fig. 4. Noting that NPDE are sensitive to the number of samples and results shown here were with setting ESAMPLE option to 10000, as lower samples resulted in poor predictions of ΔOFVOriginal.

In conclusion, the principle of model-based diagnostics post-processing for automated model building had been demonstrated and successfully applied with CWRES modeling, which is a valuable diagnostic tool for RUV model identification during model development/evaluation process, as it provides guidance for the nature and magnitude of potential RUV model misspecification/improvements.

How to Proceed in Practice

CWRES modeling can be easily implemented in analysis software; it is already implemented in PsN (available as “resmod” from version 4.7.0). The procedure requires the original NLME model file and a table with ID, TIME, CWRES, and IPRED data items from the original NLME model execution. CWRES data item can be replaced with other residuals, and DVID data item is needed in case of multiple dependent variables. TIME data item can be replaced by time after dose TAD if available. IPRED data item should be positive on normal scale for successful testing of dTBS and power error models. Options are available to account for multiple occasions and to manually set the number of time cut off points. The extended RUV models are automatically created and run; the output contains ΔOFVCWRES for each extended RUV model together with the parameters of interest for each RUV extension. Since resmod is a fast and easy to perform procedure with no limitations for continuous data, it is a good idea to always consider applying resmod when selecting between-error models for model development. Also, all parameters of the original NLME model should be re-estimated after implementing any of the extended RUV models. As we showed, these extended RUV models address different problems of the residual variability. In our preliminary results, a combination of these extended RUV models sometimes showed a better description of data; however, that was not further investigated. A previously discussed example of this was a combination of dTBS approach with t-distributed error model to address skewed residuals with outliers (7).

References

Gobburu JV. Pharmacometrics 2020. J Clin Pharmacol. 2010;50:151S–7S.

Karlsson MO, Beal SL, Sheiner LB. Three new residual error models for population PK/PD analyses. J Pharmacokinet Biopharm. 1995;23(6):651–72. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02353466.

Silber HE, Kjellsson MC, Karlsson MO. The impact of misspecification of residual error or correlation structure on the type I error rate for covariate inclusion. J Pharmacokinet Pharmacodyn. 2009;36(1):81–99. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10928-009-9112-1.

Long JS, Ervin LH. Using heteroscedasticity consistent standard errors in the linear regression model. J Am Stat. 2000;54(3):217–24. https://doi.org/10.2307/2685594.

Chi EM, Reinsel GC. Models for longitudinal data with random effects and AR(1) errors. J Am Stat Assoc. 1989;84:452–9.

Davidian M, Giltinan DM. Some general estimation methods for nonlinear mixed effects models. J Biopharm Stat. 1993;3:23–55.

Dosne A, Bergstrand M, Karlsson MO. A strategy for residual error modeling incorporating scedasticity of variance and distribution shape. J Pharmacokinet Pharmacodyn. 2015;43(2):137–51. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10928-015-9460-y.

Box GEP, Cox DR. An analysis of transformations. J R Stat Soc B. 1964;26(2):211–52.

Karlsson MO, Jonsson EN, Wiltse CG, Wade JR. Assumption testing in population pharmacokinetic models: illustrated with an analysis of Moxonidine data from congestive heart failure patients. J Pharmacokinet Biopharm. 1998;26(2):207–46.

Mould DR, Upton RN. Basic concepts in population modeling, simulation, and model-based drug development. Part 2: introduction to pharmacokinetic modeling methods. CPT Pharmacometrics Syst Pharmacol. 2013;2:e38.

Keizer RJ, Karlsson MO, Hooker AC. Modeling and simulation workbench for NONMEM: tutorial on Pirana, PsN, and Xpose. CPT Pharmacometrics Syst Pharmacol. 2013;2(6):e50.

Hooker AC, Staatz CE, Karlsson MO. Conditional weighted residuals (CWRES): a model diagnostic for the FOCE method. Pharm Res. 2007;24(12):2187–97.

Comets E, Brendel K, Mentré F. Computing normalised prediction distribution errors to evaluate nonlinear mixed-effect models: the npde add-on package for R. Comput Methods Prog Biomed. 2008;90(2):154–66.

Friberg L, Greef RD, Kerbusch T, Karlsson MO. Modeling and simulation of the time course of asenapine exposure response and dropout patterns in acute schizophrenia. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2009;86(1):84–91. https://doi.org/10.1038/clpt.2009.44.

Zingmark P, Ekblom M, Odergren T, Ashwood T, Lyden P, Karlsson MO, et al. Population pharmacokinetics of clomethiazole and its effect on the natural course of sedation in acute stroke patients. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2003;56(2):173–83. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.0306-5251.2003.01850.x.

Bogason A, Quartino AL, Lafolie P, Masquelier M, Karlsson MO, Paul C, et al. Inverse relationship between leukaemic cell burden and plasma concentrations of daunorubicin in patients with acute myeloid leukaemia. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2011;71(4):514–21. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2125.2010.03894.x.

Henning S, Friberg L, Karlsson MO. Characterizing time to conversion to sinus rhythm under digoxin and placebo in acute atrial fibrillation. PAGE 18. Abstr 1504. 2009. www.page-meeting.org/?abstract=1504.

Hornestam B, Jerling M, Karlsson MO, Held P. Intravenously administered digoxin in patients with acute atrial fibrillation: a population pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic analysis based on the digitalis in acute atrial fibrillation trial. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2003;58(11):747–55. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00228-002-0553-3.

Jonsson S, Cheng Y, Edenius C, Lees KR, Odergren T, Karlsson MO. Population pharmacokinetic modelling and estimation of dosing strategy for NXY-059, a Nitrone being developed for stroke. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2005;44(8):863–78. https://doi.org/10.2165/00003088-200544080-00007.

Jonsson S, Davidse A, Wilkins J, Walt JV, Simonsson US, Karlsson MO, et al. Population pharmacokinetics of ethambutol in south African tuberculosis patients. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2011;55(9):4230–7. https://doi.org/10.1128/aac.00274-11.

Alskär O, Bagger JI, Røge RM, Knop FK, Karlsson MO, Vilsbøll T, et al. Semimechanistic model describing gastric emptying and glucose absorption in healthy subjects and patients with type 2 diabetes. J Clin Pharmacol. 2015;56(3):340–8. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcph.602.

Hamrén B, Björk E, Sunzel M, Karlsson MO. Models for plasma glucose, HbA1c, and hemoglobin interrelationships in patients with type 2 diabetes following tesaglitazar treatment. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2008;84(2):228–35. https://doi.org/10.1038/clpt.2008.2.

Silber HE, Jauslin PM, Frey N, Gieschke R, Simonsson US, Karlsson MO. An integrated model for glucose and insulin regulation in healthy volunteers and type 2 diabetic patients following intravenous glucose provocations. J Clin Pharmacol. 2007;47(9):1159–71. https://doi.org/10.1177/0091270007304457.

El sherbiny D, Ren Y, Mcilleron H, Maartens G, Simonsson US. Population pharmacokinetics of lopinavir in combination with rifampicin-based antitubercular treatment in HIV-infected south African children. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2010;66(10):1017–23. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00228-010-0847-9.

Dorlo TP, Van Thiel PPAM, Huitema AD, Keizer RJ, Vries HJ, Beijnen JH, et al. Pharmacokinetics of miltefosine in old world cutaneous leishmaniasis patients. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2008;52(8):2855–60. https://doi.org/10.1128/aac.00014-08.

Friberg LE, Henningsson A, Maas H, Nguyen L, Karlsson MO. Model of chemotherapy-induced myelosuppression with parameter consistency across drugs. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20(24):4713–21. https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.2002.02.140.

Wahlby U, Thomson AH, Milligan PA, Karlsson MO. Models for time-varying covariates in population pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic analysis. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2004;58(4):367–77. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2125.2004.02170.x.

Karlsson MO, Wade JR, Loumaye E, Munafo A. The population pharmacokinetics of recombinant- and urinary-human follicle stimulating hormone in women. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2002;45(1):13–20. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2125.1998.00644.x.

Beal S, Sheiner LB, Boeckmann A, Bauer RJ. NONMEM User’s Guides. Icon Development Solutions, Ellicott City; 1989–2010.

Lindbom L, Pihlgren P, Jonsson EN. PsN-toolkit—a collection of computer intensive statistical methods for non-linear mixed effect modeling using NONMEM. Comput Methods Prog Biomed. 2005;79(3):241–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmpb.2005.04.005.

Team RC. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria; 2014. Available from: http://www.R-project.org.

Nyberg J, Bauer RJ, Hooker AC. Investigations of the weighted residuals in NONMEM7 PAGE 19. Abstr 1883. 2010. www.page-meeting.org/?abstract=1883.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank colleagues in Pharmacometrics research group at Uppsala University for providing their models, data, and associated investigations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.M.A.I., R.N., M.C.K., and M.O.K. wrote the manuscript. M.M.A.I., R.N., M.C.K., and M.O.K. designed the research. M.M.A.I. performed the research. M.M.A.I., R.N., M.C.K., and M.O.K. analyzed the data.

Corresponding author

Electronic Supplementary Material

ESM 1

(PDF 218 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Ibrahim, M.M.A., Nordgren, R., Kjellsson, M.C. et al. Model-Based Residual Post-Processing for Residual Model Identification. AAPS J 20, 81 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1208/s12248-018-0240-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1208/s12248-018-0240-7