Abstract

Background

Virtual patient-to-provider messaging systems such as text messaging have the potential to improve healthcare access; however, little research has used theory to understand the barriers and facilitators impacting uptake of these systems by patients and healthcare providers. This review uses the Capability-Opportunity-Motivation-Behaviour (COM-B) model and the Theoretical Domains Framework (TDF) to explore barriers and facilitators of patient-to-provider messaging.

Methods

A rapid umbrella review method was followed. Medline and CINAHL were searched for review articles that examined patient-to-provider implementation barriers and facilitators by patients or healthcare providers. Two coders extracted implementation barriers and facilitators, and one coder mapped these barriers and facilitators on to the COM-B and TDF.

Results

Fifty-nine unique barriers and facilitators were extracted. Regarding healthcare provider oriented barriers and facilitators, the most frequently identified COM-B components included Reflective Motivation (identified in 42% of provider barriers and facilitators), Psychological Capability (19%) and Physical Opportunity (19%) and TDF domains included Beliefs about Consequences (identified in 28% of provider barriers and facilitators), Environmental Context and Resources (19%), and Social Influences (17%). Regarding patient oriented barriers and facilitators, the most frequently identified COM-B components included Reflective Motivation (identified in 55% of patient barriers and facilitators), Psychological Capability (16%), and Physical Opportunity (16%) and TDF domains included Beliefs about Consequences (identified in 30% of patient barriers and facilitators), Environmental Context and Resources (16%), and Beliefs about Capabilities (11%).

Conclusions

Both patients and healthcare providers experience barriers to implementing patient-to-provider messaging systems. By conducting a COM-B and TDF-based analysis of the implementation barriers and facilitators, this review highlights several theoretical domains for researchers, healthcare systems, and policy-makers to focus on when designing interventions that can effectively target these issues and enhance the impact and reach of virtual messaging systems in the future.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Find the latest articles, discoveries, and news in related topics.Background

With the rapid adoption of virtual healthcare services seen during the COVID-19 pandemic [1,2,3,4], and widespread acceptability of mobile devices, there has been a shift towards electronic and mobile health (‘eHealth’ and ‘mHealth’, respectively) solutions to augment traditional in-person healthcare services [5]. For example, adoption of eHealth and mHealth (herein referred to as ‘virtual care’) increased dramatically, with 86% of patients in the province of British Columbia, Canada connecting with their primary care physician virtually between April and September 2020 [6]. To enhance the effectiveness of primary care during COVID-19, primary healthcare providers employed virtual care solutions for remote triage, consultations, monitoring, and prescriptions [7, 8]. The wide-scale adoption and implementation of equitable virtual care services has the potential to improve access to care, reduce risk of disease transmission, reduce tension on healthcare facilities, and support continuity of care [9].

Patient-to-provider messaging is a commonly used virtual care service defined as any virtual messaging system which facilitates written communication between a healthcare provider and their patients. Some examples of patient-to-provider messaging include text messaging, emails, or messaging embedded within smartphone applications. The low overhead costs and time commitments required for patient-to-provider messaging [10,11,12,13,14,15] has proven useful in supplementing care services and has been shown to improve adherence to health behaviours (e.g., medication adherence, appointment attendance) [16]. Patient-to-provider messaging also has the potential to improve continuity of care by providing patients with ongoing support from healthcare providers remotely [15]. Despite these promises, the sudden shift to virtual care seen during the COVID-19 pandemic has been criticized as it was implemented in haste, and may have inadvertently intensified the marginalization of those already experiencing inequities in healthcare (e.g., older adults, racialized communities, etc.) [17]. Given that virtual care appears here to stay, there is a timely need to generate evidence to inform best practices for developing and delivering equitable, person-centred virtual care via patient-to-provider messaging.

Developing theory-based interventions

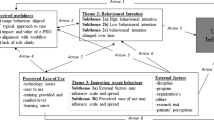

One effective approach to generate actionable evidence and support virtual care delivery is by incorporating theory into intervention development. The Behaviour Change Wheel is a comprehensive intervention development framework which includes both the Capability, Opportunity, Motivation, Behaviour (COM-B) model, and the Theoretical Domains Framework (TDF) [18]. The Behaviour Change Wheel has been widely used to guide the development of theory-based interventions for virtual care [19,20,21]. The COM-B model and TDF (refer to Fig. 1) form the core of the Behaviour Change Wheel (refer to Fig. 2), and are used at the initial stages of intervention development to identify barriers and facilitators which influence a target behaviour [22].

Theoretical domains framework depicted in yellow mapped onto the COM-B model depicted in green. TDF domains include: Soc Social influences, Env Environmental context and resources, Id Social/professional role and identity, Bel Cap Beliefs about capabilities, Opt Optimism, Int Intentions, Goals Goals, Bel Cons Beliefs about consequences, Reinf Reinforcement, Em Emotion, Know Knowledge, Cog Cognitive and interpersonal skills, Mem Memory, attention, and decision processes, Beh Reg Behavioural regulation, Phys Physical skills

The Behaviour Change Wheel (reproduced with permission from Michie, Atkins, et al., [18]). Protected by copyright

The COM-B model conceptualizes behaviour as part of a system of interacting components including an individuals capability (physical and psychological), opportunity (physical and social), and motivation (reflective and automatic) [22]. Similarly, the TDF, which is often used alongside with the COM-B model [23, 24], provides a framework of 14 theoretical domains used to explain theoretical constructs considered as determinants of behaviour [25]. The 14 TDF domains map directly onto the COM-B components [25] (see Fig. 1), allowing intervention designers the ability to use the TDF in conjunction with the COM-B. Using an integrated approach allows for the expansion of each component of the COM-B model, providing more detailed insights by incorporating the TDF [26,27,28,29,30]. Using the COM-B and TDF to examine barriers and facilitators to patient-to-provider messaging amongst existing evidence will result in a list of modifiable factors to target; listing such factors can aid designers to create theory-informed interventions, thereby potentially improving the implementation and effectiveness of virtual care services in the future.

Current study

Understanding how barriers and facilitators align with theoretical insights on behaviour change is essential for making system level improvements, healthcare service planning, and policy formulation, all of which may contribute to the sustained use of patient-to-provider messaging within virtual care services. As such, the purpose of this rapid umbrella review is to synthesize barriers and facilitators to engaging with patient-to-provider messaging using the COM-B model and TDF; this represents the first step towards intervention development according to the Behaviour Change Wheel.

Methods

A rapid umbrella review was conducting following published recommendations [31]. Rapid reviews are a form of knowledge synthesis which accelerates the process of conducting traditional systematic reviews by omitting or streamlining certain steps in the process [32], such as the number of individuals required to screen and extract data. Within the context of virtual care, in which innovations are constantly evolving, rapid reviews are better suited to provide actionable evidence in a more timely manner compared to traditional systematic or scoping reviews [31].

To improve methodological rigour the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) checklist [33] and the PRISMA flow diagram were used to outline key methodological processes (see Additional file 1 and Fig. 3, respectively). This review was registered on Open Science Framework [34].

Identify the research question

The current umbrella review aims to answer the following questions to inform recommendations for improving patient-to-provider messaging:

-

(I)

What are patient and healthcare provider barriers and facilitators to engaging with patient-to-provider messaging?

-

(II)

What COM-B components and TDF domains should be targeted in future patient-to-provider messaging services to improve implementation and uptake?

Identify relevant studies

Medline and CINAHL were searched for studies relating to: (I) patient-to-provider messaging (e.g., MeSH terms “text messaging”, keywords “short messag* service*”, “email”), (II) barriers, facilitators, or best practice (e.g., MeSH terms “communication barriers”, keywords “best practice*”), and (III) review articles. Databases were searched from inception until November 2022. The full search strategy can be found on the published registration [34], and the Medline search strategy can be found in Additional file 2.

Eligibility criteria

For inclusion criteria as it related to the Population, Intervention, Comparator groups, and Outcomes (PICO), see Table 1. To improve the timeliness of this review, articles were limited to review type articles (including any type of review article; e.g., narrative, rapid, scoping, systematic, qualitative, scans, etc.). Conference proceedings, newspaper articles, dissertations, and non-peer review articles were excluded. To be included, review articles had to refer to the use of patient-to-provider messaging in the context of healthcare. No limits on date of publication, geographical location, or research setting (e.g., lab, community, hospital) were imposed. Only studies published in English were included.

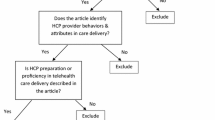

Study screening and selection

All studies obtained from the search were uploaded into the systematic review software Covidence (Veritas Health Innovation Ltd., Melbourne, Australia) for processing. Removal of duplicate studies was completed automatically within Covidence. Following this, one author (MM) completed title and abstract screening. Full-text screening was performed by two authors (MM and SK). First, a sample of five records was screened independently by both authors to determine the degree of consistency in individual assessment, which subsequently yielded 100% agreement. Due to the high levels of agreement, the remaining full-texts were screened by a single reviewer for inclusion to improve the timeliness of this review.

Charting and extracting the data

A custom data extraction form was developed to characterize general study information (author, title, year of publication, review location, review type); participant information (gender, sex, age, ethnicity, race, health status); and a description of the patient-to-provider messaging system assessed (type of virtual messaging, barriers, facilitators). Two reviewers independently extracted data from half of the articles with 20% checked by both reviewers.

Protocol deviations

While the published registration states that quality evaluation/risk of bias was not going to be assessed, review authors felt that contextualizing the rapid review within the quality of evidence would benefit readers and healthcare authorities wishing to utilize this information in their decision making; therefore, a risk of bias was completed by both authors using the Assessment of Multiple Systematic Reviews (AMSTAR) 2 tool [35]. This tool evaluates the quality of review articles by answering 16 items. Five items (4, 9, 11, 12, and 15) are considered “critical” domains. Study quality was defined as high (none or 1 non-critical weakness), moderate (> 1 non-critical weakness), low (1 critical weakness), and critically low (> 1 critical weakness). Further, to increase the generalizability of results, one author (MM) used the TDF and COM-B to code all extracted barriers facilitators according to the 14 TDF domains and 6 COM-B components.

Results

After de-duplication, the search resulted in 796 records. Of these, 69 were included for full-text review, resulting in a total of 12 included review articles (see Fig. 3). Reviews were conducted primarily in the United States [36,37,38], Canada [39, 40], and the United Kingdom [41, 42], with remaining reviews conducted in Australia [43], China [44], Denmark [45], Germany [46], and New Zealand [47]. Reviews were published from 2009 until 2022, with the majority (92%) published in the past 10 years.

From the 12 included reviews, five (42%) were scoping reviews [37,38,39, 44, 46], four (33%) were systematic reviews [36, 40, 41, 43], two (17%) were narrative reviews [42, 45], and one (8%) was an integrative literature review [47]. Reviews included studies targeting both patient/caregiver and healthcare provider perspectives across a variety of patient populations (older adults, patients in rural settings, and those with HIV, diabetes, cancer, or overweight and obesity). Only four reviews (33%) summarized demographic information beyond the patient condition being treated [36, 38, 43, 44], none of which provided information on participant race, ethnicity, culture, or socio-economic status.

Patient-to-provider messages were sent via multiple modalities including text messaging, social media, emails, and web-messaging. Barriers and facilitators to implementing or engaging with patient-to-provider messaging were identified in 10 studies (83%), one study outlined facilitators only, and one outlined barriers only. A total of 59 unique barriers and facilitators were identified; see Table 2 for specific barriers and facilitators identified for patients, and Table 3 for barriers and facilitators identified for healthcare providers.

Barriers

Of the 27 unique barriers identified amongst both populations, 21 (78%) were oriented towards the healthcare provider or clinical practice (e.g., addition of technology results in healthcare providers having to add “tech support” to their scope of practice), and 19 (70%) were oriented towards the patient (e.g., digital health literacy). Interestingly, from this list of 27 barriers, a total of 13 (48%) were coded as being oriented towards both the patient and provider (e.g., blurring of boundaries in the relationship).

Across studies, the most frequent barriers extracted were related to privacy and confidentiality (reported in n = 7 reviews; 58%; TDF = Environmental Context and Resources and Beliefs about Consequences; COM-B = Physical Opportunity’ and Reflective Motivation), technical problems (n = 3; 25%; TDF = Knowledge and Environmental Context and Resources; COM-B = Psychological Capability and Physical Opportunity), disparities in internet access (n = 3; 25%; TDF = Environmental Context and Resources; COM-B = Physical Opportunity), affordability of technology for patient and clinician/practice (n = 3; 25%; TDF = Environmental Context and Resources; COM-B = Physical Opportunity), perceived increase in clinician workload (n = 3; 25%; TDF = Beliefs about Consequences; COM-B = Reflective Motivation), and a lack of clinician training (n = 3; 25%; TDF = Skills, Knowledge, and Environmental Context and Resources; COM-B = Physical Capability, Psychological Capability, and Physical Opportunity).

Provider barriers

The most frequently coded TDF domains relating to barriers for healthcare providers engaging with patient-to-provider messaging were Environmental Context and Resources (n = 5 out of 21 provider-oriented barriers; 24%), Beliefs about Consequences (n = 5; 24%), Knowledge (n = 3; 14%), and Social or Professional Role and Identity (n = 3; 14%). See Table 4 for information on all domains.

Regarding the COM-B, Motivation was the most the most frequently identified components for healthcare provider barriers (n = 9; 43% barriers identified within the sub domain Reflective Motivation; n = 0; 0% Automatic motivation), followed by Opportunity (n = 5; 24% Physical Opportunity, n = 2; 10% Social Opportunity), then Capability (n = 4; 19% Psychological Capability, n = 1; 5% Physical Capability).

Patient barriers

The most frequently coded TDF domains relating to barriers for patients engaging with patient-to-provider messaging were Environmental Context and Resources (n = 5 out of 19 patient-oriented barriers; 26%), and Beliefs about Consequences (n = 5; 26%). See Table 4 for information on all domains.

Regarding the COM-B, Motivation was the most the most frequently identified category for patient barriers (n = 11; 58% barriers identified within the sub domain Reflective Motivation; n = 0; 0% Automatic motivation), followed by Opportunity (n = 5; 26% Physical Opportunity, n = 0; 0% Social Opportunity), then Capability (n = 2; 11% Psychological Capability, n = 1; 5% Physical Capability).

Facilitators

Of the 32 unique facilitators identified, 15 (47%) were oriented towards the healthcare provider or clinical practice, and 25 (78%) towards the patient. Interestingly, from this list of 32 facilitators, a total of 8 (25%) were coded as being oriented towards both the patient and provider.

Across studies, the most frequent facilitators identified were related to patients feeling empowered to ask questions via virtual messaging that they may otherwise not have asked (n = 4; 33%; TDF = Beliefs about Capabilities, Social or Professional Roles and Identity; COM-B = Reflective Motivation), improved access to information (n = 3; 25%; TDF = Beliefs about Consequences; COM-B = Reflective Motivation), having a written record aids recall (n = 3; 25%; TDF = Memory, Attention, and Decision Processes; COM-B = Psychological Capability), and reduced travel time (n = 3; 25%; TDF = Beliefs about Consequences; COM-B = Reflective Motivation).

Provider facilitators

The most frequently identified TDF domains relating to facilitators for healthcare providers engaging with patient-to-provider messaging were Beliefs about Consequences (n = 5 out of 15 provider-oriented facilitators; 33%), and Social Influences (n = 4; 27%). See Table 4 for information on all domains.

Regarding the COM-B, Motivation (n = 6; 40% barriers identified within the sub domain Reflective Motivation; n = 0; 0% Automatic motivation) and Opportunity (n = 2; 13% Physical Opportunity, n = 4; 27% Social Opportunity) were the most the most frequently identified COM-B components for healthcare provider facilitators, followed by Capability (n = 3; 20% Psychological Capability, n = 0; 0% Physical Capability).

Patient facilitators

The most frequently identified TDF domains relating to facilitators for patients engaging with patient-to-provider messaging were Beliefs about Consequences (n = 8 out of 25 patient-oriented facilitators; 32%), Beliefs about Capabilities (n = 3; 12%), and Memory, Attention, and Decision Processes (n = 3; 12%). See Table 4 for information on all domains.

Regarding the COM-B, Motivation was the most the most frequently identified category for patient facilitators (n = 13; 52% barriers identified within the sub domain Reflective Motivation; n = 3; 12% Automatic motivation), followed by Capability (n = 5; 20% Psychological Capability, n = 0; 0% Physical Capability), and then Opportunity (n = 2; 8% Physical Opportunity, n = 2; 8% Social Opportunity).

Study quality

From the 12 included reviews, none were of high quality, 3 were moderate, 8 were low, and 1 was of critically low quality (Additional file 3 shows the AMSTAR 2 evaluation for all included reviews). All, or nearly all, of the included reviews reported on: all PICO components within the research question (item 1), literature search (item 4), details on included studies (item 8), and discussion of heterogeneity in results (item 14). None, or nearly none, of the included reviews reported on: a priori protocol (item 2), risk of bias assessment (item 9), information on funding sources (item 10), and accounting for risk of bias in interpretation (item 13).

Discussion

The development and implementation of patient-to-provider messaging is paramount to providing a cost-efficient, sustainable, and accessible form of text-based virtual care. With that said, various barriers and facilitators exist towards its adoption and effectiveness. The current rapid umbrella review represents the first systematic analysis and integration of barriers and facilitators associated with patient-to-provider messaging using the TDF and COM-B model. While use of the TDF or COM-B model to synthesize research literature is a relatively new concept [48], both have previously guided data analysis in other reviews focused on health behaviours and interventions [49,50,51].

This review provides valuable insights into the factors affecting healthcare providers and patients when using virtual messaging services, and highlights that both encounter numerous barriers and facilitators to implementing and engaging with patient-to-provider messaging. Further, the barriers and facilitators identified in this review span all COM-B components and all TDF domains (except for Goals); the most commonly identified COM-B category was Reflective Motivation which was identified in 39 out of the 59 unique barriers and facilitators (66%). Of the 39 barriers which fell within Reflective Motivation, the majority were further specified as Beliefs about Consequences using the TDF (23/39; 60%).

Barriers

The results of this review indicate that barriers to patient-to-provider messaging are almost evenly distributed within the literature between healthcare providers (8/27 barriers oriented towards providers alone; 30%) and patients (6/27 barriers oriented towards patients alone; 22%), with 13 out of 27 barriers (48%) affecting both groups. Barriers oriented towards healthcare providers were primarily found within the TDF domains Environmental Context and Resources, Beliefs about Consequences, Knowledge, and Social or Professional Role and Identity, and COM-B components of Reflective Motivation, Physical Opportunity, and Psychological Capability. These provider barriers focused on aspects such as the addition of technology to their scope of practice, perceived increases in workload, and a lack of training. Patient-oriented barriers were primarily found within the TDF domains Environmental Context and Resources and Beliefs about Consequences, and the COM-B components of Reflective Motivation and Physical Opportunity. These patient barriers highlight the importance of addressing issues such as digital health literacy and disparities in internet access. Notably, privacy and confidentiality emerged as a prominent barrier across studies for both healthcare providers and patients, emphasizing the significance of ensuring data security and privacy safeguards in patient-to-provider messaging.

Facilitators

Results demonstrate a higher proportion of facilitators oriented towards patients (17/32 barriers oriented towards patients alone; 53%) compared to healthcare providers (7 barriers oriented towards providers alone; 22%), with only 8 out of 32 barriers (25%) spanning both groups. For healthcare providers, the TDF domains Beliefs about Consequences and Social Influences and COM-B components Reflective Motivation and Social Opportunity were the most frequently identified facilitators. The asynchronous nature of messaging allows healthcare providers to consult with colleagues and provide more considered responses, thereby allowing them the opportunity to prioritize the content of their messages to build and maintaining rapport with their patients. Contrary to the experiences noted as barriers, providers reported a perceived decrease in workload once patient-to-provider messaging was integrated into their clinical practice. This finding suggests that highlighting the potential benefits of improved efficiency and productivity through messaging could enhance provider motivation to adopt messaging practices.

Patient related facilitators were primarily found within the TDF domains Beliefs about Consequences, Beliefs about Capabilities, and Memory, Attention, and Decision Processes, and COM-B components of Reflective motivation, and Psychological Capability. These patient facilitators emphasized patients feeling empowered to ask questions, improved access to information, the aid of written records in recall, and reduced travel time. The findings suggest that patient-to-provider messaging has the potential to enhance patient engagement, information accessibility, and convenience, thereby enabling patients to play a more active role in their healthcare.

An interesting finding from this review is the potential impact of patient-to-provider messaging on the therapeutic relationship, as indicated by barriers and facilitators from both healthcare providers and patients. Patients reported feeling more comfortable sharing sensitive information through messaging, which they otherwise might not feel comfortable discussing in person. Additionally, the asynchronous nature of messaging allows patients to ask relevant questions at their convenience. However, providers expressed concerns about the informal nature of messaging and its potential to blur the patient-provider relationship. These results appear to underscore the importance of maintaining appropriate boundaries and ensuring clear communication channels within text-based patient-to-provider messaging.

Developing patient-to-provider messaging interventions to target barriers and facilitators

The current analysis of barriers and facilitators using the COM-B model and TDF provides a “behavioural diagnosis” of potentially modifiable factors which enables a target behaviour to occur, and can be linked to intervention functions and behaviour change techniques through the guidance of the Behaviour Change Wheel [18]. By using the COM-B model, TDF, and associated intervention functions linked by the Behaviour Change Wheel, future researchers can develop and implement theory-based solutions to address barriers and promote facilitators identified within this review. Specifically, using the Behaviour Change Wheel, the most commonly identified TDF domains and COM-B components correspond to the following intervention functions: Training, Restriction, Environmental Restructuring, Enablement, Education, Persuasion, and Modelling [18]. For an example of how the Behaviour Change Wheel can be used in conjunction with the COM-B model and TDF for intervention design, see Fig. 4. Additionally, for example policy and clinical solutions for the top identified barriers in this review, see Table 5.

Strengths and limitations

While the primary strength of this review is the use of the COM-B model and the TDF to categorize provider- and patient-level barriers and facilitators influencing the implementation of virtual care identified in previous research on patient-to-provider messaging, it is important to also recognize its limitations. In conducting this umbrella review, a rapid review methodology was used which streamlines the systematic review process while also potentially introducing bias into specific review steps. For example, a limited number of databases were searched, and inclusion was limited to English language review articles. By limiting to only review type articles, the authors did not have access to the raw data from each article within eligible reviews; therefore only barriers and facilitators that were reported within the review articles could be extracted and coded, and findings may not encompass the full range of factors influencing implementation of patient-to-provider virtual messaging. Further, the majority of screening and data extraction, and the entirety of the TDF coding was completed by a single author to expedite the review process. Future research should consider a formal systematic review that includes patient-to-provider messaging from other article types to provide more comprehensive and generalizable findings.

Most of the included reviews were assessed as having low confidence (Additional file 3). Specifically, many reviews lacked an a priori study protocol, and a quality assessment of included studies. Another important limitation for this work is the lack of demographic reporting within the included reviews. Only four of the twelve included reviews summarized demographic information beyond the patient condition being treated, and none provided information on participant race, ethnicity, culture, or socio-economic status. Such important factors are likely to influence barriers and facilitators for implementing and engaging with patient-to-provider virtual messaging and limit generalizability of these results. Future research should prioritize collecting and reporting on demographic information to identify any differences in barriers and facilitators of patient-to-provider virtual messaging experienced by different populations so that potential differences in the perception of barriers and facilitators of patient-to-provider virtual messaging can be identified and addressed.

Conclusions

This rapid umbrella review provides insights into the barriers and facilitators to implementing patient-to-provider messaging services (e.g., text messaging) within healthcare settings. Barriers and facilitators were primarily associated with the COM-B components Reflective Motivation, Psychological Capability, and Physical Opportunity and TDF domains Beliefs about Consequences, Environmental Contexts and Resources, Social Influences, and Beliefs about Capabilities. Using a COM-B model and TDF-based analysis, this review offers a theoretical foundation for researchers, healthcare systems, and policy-makers to design interventions that can effectively target potential implementation issues thus enhancing the impact and accessibility of patient-to-provider messaging systems in the future.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- AMSTAR:

-

A MeaSurement Tool to Assess systematic Reviews

- BCT:

-

Behaviour Change Technique

- BCW:

-

Behaviour Change Wheel

- COM-B:

-

Capability, Opportunity, Motivation, Behaviour model for behaviour change

- eHealth:

-

Electronic health

- IF:

-

Intervention functions

- mHealth:

-

Mobile health

- PICO:

-

Population, intervention, comparator group, outcomes

- TDF:

-

Theoretical Domains Framework

References

Wong AKC, Wong FKY, Chow KKS, Wong SM, Lee PH. Effect of a telecare case management program for older adults Who Are homebound during the COVID-19 pandemic: a pilot randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(9):e2123453–e2123453.

Colbert GB, Venegas-Vera AV, Lerma EV. Utility of telemedicine in the COVID-19 era. Rev Cardiovasc Med. 2020;21(4):583–7.

Mann DM, Chen J, Chunara R, Testa PA, Nov O. COVID-19 transforms health care through telemedicine: evidence from the field. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2020;27(7):1132–5.

Hincapié MA, Gallego JC, Gempeler A, Piñeros JA, Nasner D, Escobar MF. Implementation and usefulness of telemedicine during the COVID-19 pandemic: a scoping review. J Prim Care Community Health. 2020;11:2150132720980612.

Canadian Institute for Health Information. How Canada Compares: Results From the Commonwealth Fund’s 2021 International Health Policy Survey of Older Adults in 11 Countries. Ottawa: CIHI; 2022.

Canada H. Virtual care policy framework. 2022 [cited 2022 Sep 22]. Available from: https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/corporate/transparency/health-agreements/bilateral-agreement-pan-canadian-virtual-care-priorities-covid-19/policy-framework.html

Kumpunen S, Webb E, Permanand G, Zheleznyakov E, Edwards N, van Ginneken E, et al. Transformations in the landscape of primary health care during COVID-19: themes from the European region. Health Policy. 2022;126(5):391–7.

Joy M, McGagh D, Jones N, Liyanage H, Sherlock J, Parimalanathan V, et al. Reorganisation of primary care for older adults during COVID-19: a cross-sectional database study in the UK. Br J Gen Pract. 2020;70(697):e540–7.

Demeke HB, Pao LZ, Clark H, Romero L, Neri A, Shah R, et al. Telehealth practice among health centers during the COVID-19 pandemic—United States, July 11–17, 2020. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(50):1902.

Hall AK, Cole-Lewis H, Bernhardt JM. Mobile text messaging for health: a systematic review of reviews. Annu Rev Public Health. 2015;36:393–415.

Shaw R, Bosworth H. Short message service (SMS) text messaging as an intervention medium for weight loss: a literature review. Health Inf J. 2012;18(4):235–50.

Car J, Gurol-Urganci I, de Jongh T, Vodopivec-Jamsek V, Atun R. Mobile phone messaging reminders for attendance at healthcare appointments. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;7:CD007458.

Perron NJ, Dao MD, Righini NC, Humair J-P, Broers B, Narring F, et al. Text-messaging versus telephone reminders to reduce missed appointments in an academic primary care clinic: a randomized controlled trial. BMC Health Serv Res. 2013;13(1):125.

Free C, Phillips G, Watson L, Galli L, Felix L, Edwards P, et al. The effectiveness of mobile-health technologies to improve health care service delivery processes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 2013;10(1): e1001363.

Dash J, Haller DM, Sommer J, Junod PN. Use of email, cell phone and text message between patients and primary-care physicians: cross-sectional study in a French-speaking part of Switzerland. BMC Health Serv Res. 2016;16(1):1–7.

Schwebel FJ, Larimer ME. Using text message reminders in health care services: a narrative literature review. Internet Interv. 2018;13:82–104.

D’cruz M, Banerjee D. ‘An invisible human rights crisis’: the marginalization of older adults during the COVID-19 pandemic–An advocacy review. Psychiatry Res. 2020;292: 113369.

Michie S, Atkins L, West R. The behaviour change wheel. In: A guide to designing interventions. 1st ed. Great Britain: Silverback Publishing; 1003, 2014. p. 1010.

Chiang N, Guo M, Amico KR, Atkins L, Lester RT. Interactive two-way mHealth interventions for improving medication adherence: an evaluation using the behaviour change wheel framework. JMIR MHealth UHealth. 2018;6(4): e9187.

Truelove S, Vanderloo LM, Tucker P, Di Sebastiano KM, Faulkner G. The use of the behaviour change wheel in the development of ParticipACTION’s physical activity app. Prev Med Rep. 2020;20: 101224.

English C, Attia JR, Bernhardt J, Bonevski B, Burke M, Galloway M, et al. Secondary prevention of stroke: study protocol for a telehealth-delivered physical activity and diet pilot randomized trial (ENAbLE-Pilot). Cerebrovasc Dis. 2021;50(5):605–11.

Michie S, Campbell R, Brown J, West R. ABC of behaviour change theories. London: Silverback Publishing; 2014.

Alexander KE, Brijnath B, Mazza D. Barriers and enablers to delivery of the Healthy Kids Check: an analysis informed by the Theoretical Domains Framework and COM-B model. Implement Sci. 2014;9(1):1–14.

Cassidy C, Bishop A, Steenbeek A, Langille D, Martin-Misener R, Curran J. Barriers and enablers to sexual health service use among university students: a qualitative descriptive study using the theoretical domains framework and COM-B model. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18(1):1–12.

Cane J, O’Connor D, Michie S. Validation of the theoretical domains framework for use in behaviour change and implementation research. Implement Sci. 2012;7:1–17.

Connell LA, McMahon NE, Tyson SF, Watkins CL, Eng JJ. Mechanisms of action of an implementation intervention in stroke rehabilitation: a qualitative interview study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2016;16:1–10.

Courtenay M, Rowbotham S, Lim R, Peters S, Yates K, Chater A. Examining influences on antibiotic prescribing by nurse and pharmacist prescribers: a qualitative study using the theoretical domains framework and COM-B. BMJ Open. 2019;9(6): e029177.

Fulton EA, Brown KE, Kwah KL, Wild S. StopApp: using the behaviour change wheel to develop an app to increase uptake and attendance at NHS Stop Smoking Services. In Healthcare. 2016;4(2):31. MDPI.

Handley MA, Harleman E, Gonzalez-Mendez E, Stotland NE, Althavale P, Fisher L, et al. Applying the COM-B model to creation of an IT-enabled health coaching and resource linkage program for low-income Latina moms with recent gestational diabetes: the STAR MAMA program. Implement Sci IS. 2016;11(1):73.

Templeton AR, Young L, Bish A, Gnich W, Cassie H, Treweek S, et al. Patient-, organization-, and system-level barriers and facilitators to preventive oral health care: a convergent mixed-methods study in primary dental care. Implement Sci. 2015;11(1):1–14.

MacPherson MM, Wang RH, Smith EM, Sithamparanathan G, Sadiq CA, Braunizer AR. Rapid Reviews to Support Practice: A Guide for Professional Organization Practice Networks. Can J Occup Ther. 2022;0(0). https://doi.org/10.1177/00084174221123721.

Garritty C, Gartlehner G, Nussbaumer-Streit B, King VJ, Hamel C, Kamel C, et al. Cochrane Rapid Reviews Methods Group offers evidence-informed guidance to conduct rapid reviews. J Clin Epidemiol. 2021;130:13–22.

Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, O’Brien KK, Colquhoun H, Levac D, et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(7):467–73.

MacPherson M. How Can Healthcare Providers Optimally Engage Patients using Virtual Messaging Systems? A Rapid Review. 2022. https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/8KW6U.

Shea B J, Reeves B C, Wells G, Thuku M, Hamel C, Moran J, et al. AMSTAR 2: a critical appraisal tool for systematic reviews that include randomised or non-randomised studies of healthcare interventions, or both. BMJ. 2017;358:j4008. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.j4008.

Buchholz SW, Wilbur J, Ingram D, Fogg L. Physical activity text messaging interventions in adults: a systematic review. Worldviews Evid Based Nurs. 2013;10(3):163–73.

Lee SA, Zuercher RJ. A current review of doctor–patient computer-mediated communication. J Commun Healthc. 2017;10(1):22–30.

Kerrigan A, Kaonga NN, Tang AM, Jordan MR, Hong SY. Content guidance for mobile phones short message service (SMS)-based antiretroviral therapy adherence and appointment reminders: a review of the literature. AIDS Care. 2019;31(5):636–46.

LeBlanc M, Petrie S, Paskaran S, Carson DB, Peters PA. Patient and provider perspectives on eHealth interventions in Canada and Australia: a scoping review. Rural Remote Health. 2020;20(3):5754.

Wijeratne DT, Bowman M, Sharpe I, Srivastava S, Jalink M, Gyawali B. Text messaging in cancer-supportive care: a systematic review. Cancers. 2021;13(14):3542.

van Velthoven MHMMT, Brusamento S, Majeed A, Car J. Scope and effectiveness of mobile phone messaging for HIV/AIDS care: a systematic review. Psychol Health Med. 2013;18(2):182–202.

Barnard-Kelly K. Utilizing eHealth and telemedicine technologies to enhance access and quality of consultations: it’s not what you say, it’s the way you say it. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2019;21(S2):S241–7.

Macdonald EM, Perrin BM, Kingsley MI. Enablers and barriers to using two-way information technology in the management of adults with diabetes: A descriptive systematic review. J Telemed Telecare. 2018;24(5):319–40.

Lyu M, Zhao Q, Yang Y, Hao X, Qin Y, Li K. Benefits of and barriers to telehealth for the informal caregivers of elderly individuals in rural areas: a scoping review. Aust J Rural Health. 2022;30(4):442–57.

Basevi R, Reid D, Godbold R. Ethical guidelines and the use of social media and text messaging in health care: a review of literature. N Z J Physiother. 2014;42(2):68–80.

Wallwiener M, Wallwiener CW, Kansy JK, Seeger H, Rajab TK. Impact of electronic messaging on the patient-physician interaction. J Telemed Telecare. 2009;15(5):243–50.

Fage-Butler AM, Jensen MN. The relevance of existing health communication models in the email age: an integrative literature review. Commun Med Equinox Publ Group. 2015;12(2/3):117–28.

Little EA, Presseau J, Eccles MP. Understanding effects in reviews of implementation interventions using the Theoretical Domains Framework. Implement Sci. 2015;10(1):1–16.

Richardson M, Khouja CL, Sutcliffe K, Thomas J. Using the theoretical domains framework and the behavioural change wheel in an overarching synthesis of systematic reviews. BMJ Open. 2019;9(6): e024950.

Rosário F, Santos MI, Angus K, Pas L, Ribeiro C, Fitzgerald N. Factors influencing the implementation of screening and brief interventions for alcohol use in primary care practices: a systematic review using the COM-B system and Theoretical Domains Framework. Implement Sci. 2021;16:1–25.

Cox NS, Oliveira CC, Lahham A, Holland AE. Pulmonary rehabilitation referral and participation are commonly influenced by environment, knowledge, and beliefs about consequences: a systematic review using the Theoretical Domains Framework. J Physiother. 2017;63(2):84–93.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge that this work was conducted within the Fraser Health Authority. Fraser Health provides care on the unceded and traditional homelands of the Coast Salish and Nlaka’pamux Nations.

Funding

This work was supported by the Virtual Health Team grant from the Health Research Foundation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MM was responsible for all aspects of this review. SK was responsible for data collection and analyses. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) Checklist.

Additional file 2.

MEDLINE Search Strategy.

Additional file 3.

AMSTAR ratings for all included reviews.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

MacPherson, M.M., Kapadia, S. Barriers and facilitators to patient-to-provider messaging using the COM-B model and theoretical domains framework: a rapid umbrella review. BMC Digit Health 1, 33 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s44247-023-00033-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s44247-023-00033-0