Abstract

Background

This study aims to propose surgical approaches intended to localize and preserve the marginal mandibular nerve (MMN) during routinely performed head and neck surgical procedures.

Main body of abstract

Preservation of the functional integrity of the MMN is a critical measure in the success of orofacial surgeries involving the submandibular triangle. This study systematically reviews the anatomical description of the nerve including origin, course relative to fascial planes, relation to the parotid gland and facial pedicle, branching pattern and anastomosis of nerve and consolidate the findings of several significant studies to determine the “surgically safe” approaches to avoid iatrogenic injury to MMN.

Short conclusion

The systematic approaches described in this study have helped the authors precisely determine which particular MMN preserving approach to be adopted for each aspect of head and neck surgery. This has definitely enhanced the quality of surgery performed and the postoperative satisfaction of the patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

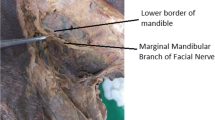

Marginal mandibular nerve is a terminal branch of the extracranial part of the facial nerve and leaves the parotid from its antero-inferior border and travels beneath the platysma muscle and deep cervical neck fascia, after which its course becomes superficial to the facial vessels. From the inferior border of the mandible, the nerve turns upwards across the body of mandible where it gives off motor innervations to risorius, depressor anguli oris, depressor labii inferioris, and mentalis, thereby maintaining facial symmetry during various facial expressions.

Iatrogenic marginal mandibular nerve injuries are common during maxillofacial surgical procedures. It has been documented that the incidence of marginal mandibular nerve (MMN) injury depends on the surgery performed and can range from 0 to 20% after excision of submandibular gland [1,2,3], 5.6 to 16.3% after parotidectomy and up to 23% after neck dissection [4, 5].

Injury to the nerve results in esthetic and functional deformity. Such deficits can affect the patient’s quality of life and have several legal implications [6]. The esthetic deformity that results during crying has been termed as “asymmetric crying facies” [7, 8]. The functional impairment is in the form of salivary incontinence.

It is imperative to have a clear understanding of its anatomical course, surface, and surgical landmarks that help in nerve localization, along with accurate knowledge on surgical approaches to obviate the detriment caused by nerve palsy.

We have revisited the previously described techniques to identify and preserve the MMN and proposed our techniques with an anatomical basis.

Main text

Sandwich technique

A flap is raised by dissecting under the submandibular gland fascia in primary cases involving the submandibular region and the nerve is preserved as it is sandwiched between the platysma and submandibular fascia (Figs. 1, 2, and 3). A modification of this is used in re-operative cases by raising a flap below the superficial layer of deep cervical fascia, below the hyoid bone, so the nerve is sandwiched between this fascia and platysma muscle (Figs. 4, 5, and 6).

Node of Stahr approach

The facial node is identified (Fig. 7) and dissection is done medially to it to expose the facial artery (Figs. 8, 9, 10, and 11). The facial artery is ligated below the lower mandibular margin to preserve the nerve.

Hayes-Martin approach

The facial vein is identified and ligated over the surface of the submandibular gland at two fingerbreadths below the mandible and the ligated vein is flipped superiorly by retracting the superficial cervical fascia, as in the majority of cases, the nerve courses over the facial vein (Figs. 12 and 13).

Parotid-masseteric fascia approach

The parotid-masseteric fascia is opened below the platysma, along the course of the facial nerve in the region of angle of the mandible to identify and preserve it (Figs. 14 and 15).

Pterygo-masseteric sling approach

The pterygo-masseteric sling is incised to retract the masseter as the nerve travels over the masseter muscle (Figs. 16 and 17).

Pouch technique

The neck skin is incised and the flap is raised in a subcutaneous dissection plane till the area of interest is reached. Then, the platysma-SMAS window is opened and dissection is performed between the branches of the facial nerve (Figs. 18, 19, and 20). This technique avoids a large area of subplatysmal dissection.

Discussion

Surgical anatomy and related considerations

Relation to parotid gland

The marginal mandibular nerve (MMN) leaves from anterior caudal margin of the parotid gland underneath the parotid-masseteric and deep cervical neck fascia just below the angle of the mandible and is anatomically protected by a thick superficial musculo-aponeurotic system (SMAS) after it exits the parotid gland [9] (Fig. 21). A systematic meta-analysis report by Marcuzzo et al. [10] reported a prevalence of 30% for MMN originating at the parotid apex and 20% originating at the anterior border of the parotid and established the nerve location relative to the parotid gland. The results suggest that the nerve is above the parotid gland in 76% and below in 18% cases. Study report by Atif et al. [11] shows that in 95% of cases, MMN exits the parotid gland from its anterior border. This is in contrast to reports by Khanfour et al. [12] which concludes that the nerve originates from the parotid apex in 70% cases and is consistent with studies by Batra et al. [13]. The parotid-masseteric fascia technique for approaching condyle using a periangular approach is proposed considering the origin and course of MMN in the parotid region (Figs. 14 and 15).

Relation to facial vessels

In majority of cases, the MMN has been reported to course above the lower border of the mandible [14] (Fig. 23). However, in 19% cases, as reported by Owsley et al. [15], the nerve runs 1–3 cm beneath the lower mandibular margin and penetrates the deep cervical fascia close to the insertion of the masseter muscle at its anterior border to become superficial to the facial artery. The importance of the facial artery as a landmark to localize the nerve was highlighted by Balagopal et al. [16] in their study and they concluded that the mean distance from the lower mandibular margin to where MMN intersects the facial artery, considering all branches of the nerve, was found to be 1.73 mm. Huettner et al. [17] established the “masseteric fusion zone” as the most likely area of iatrogenic injury to the facial nerve during SMAS release. This zone is described at an average distance of 23.1 mm from the gonial angle along the inferior mandibular margin where the MMN exits parotid-masseteric fascia to enter the subplatysmal plane. Further, Hazani et al. [9] proposed that the MMN crosses above the facial artery at about one-fourth distance from the masseteric tuberosity up to mandibular midline and can be used as a reliable landmark for nerve localization. Meta-analysis by Marcuzzo et al. [10] concluded that the MMN lies superficial to facial artery in 44% cases when the nerve has multiple branches and 36% cases when a single nerve branch is found. However, they emphasized that the relation to the anterior facial vein (AFV) is more constant and reliable as the nerve lies superficial to AFV in most cases.

Seckel [18] described the area close to the crossing point of nerve over facial vessels as “danger zone” in which the platysma-SMAS thins out exposing the MMN to a higher risk of iatrogenic injury. This zone is described as an area of 2 cm radius with the center located at a point 2 cm posterior to labial commissure. Safe dissections in this zone can be ensured by planning dissections superficial to platysma-SMAS as the nerve transits into the subplatysmal plane when it meets the facial artery along the inferior mandibular margin. Blunt dissection is done above the masseteric fascia to mobilize a SMAS-platysma flap sufficiently and care must be taken not to dissect deeper to investing fascia [15]. The prominence of the mandibular body and fibrous adhesions of masseteric ligaments in this region can make the plane of dissection enigmatic [19].

Based on previous cadaver dissection studies, the course of MMN anterior to the facial artery is above the lower mandibular margin. The nerve lies above inferior mandibular margin posterior to facial artery in 81% cases and below the inferior border in 19% cases, with its branches within a radius of 1 cm below the inferior mandibular margin as reported by Dingman and Grabb [20]. However, Wang et al. [21] concluded that in 67% of specimens, the nerve is above the inferior mandibular margin posterior to facial artery and in 33% specimens below the inferior border (Fig. 22).

Although the facial artery is a significant landmark in localizing the MMN, the facial vein is considered a definitive landmark as it exhibits a more dependable relationship with MMN, and the nerve is found lateral to the facial vein in 95% of cases [13]. The prevalence of single-branched MMN coursing on the lateral aspect of the anterior facial vein is reported to be 38% and 57% when multiple branches of nerve were found [10] (Fig. 23).

Based on the relation of the nerve to the facial artery, we recommend the node of the Stahr approach, which can be used to identify MMN by localizing facial artery during mandibular body traumatic surgeries (Figs. 7, 8, 9, 10, and 11). We suggest the use of pterygo-masseteric sling approach for surgeries involving the ramus of mandible, as the nerve anatomically courses underneath masseteric fascia and above the masseter muscle (Figs. 16 and 17).

Relation to perifacial lymph nodes

A common instance for MMN palsy is during surgical approaches to submandibular region [12, 22,23,24,25,26,27,28]. The MMN is more often jointly found with perifacial lymph nodes in the submandibular triangle (Fig. 24). It is imperative to remove these nodes as they are primary lymphatic draining sites for oral carcinomas and show an increased risk of metastasis [29]. Møller et al. [30] concluded that neck dissections involving level Ib nodes showed the highest incidence of iatrogenic MMN injury. Oncological safety of the nerve during surgical neck dissection maneuvers has been discussed in several studies [25, 31,32,33]. The Hayes-Martin technique is a long-established nerve preservation technique used during surgical neck dissections. Tirelli et al. [34] performed 63 neck dissections and concluded that the anterior perifacial nodes were in contact with a nerve in 60% cases and the other nodes were < 5 mm away from the MMN and that in 59% dissections the Hayes-Martin maneuver failed to remove all the perifacial nodes involved. These observations are in line with our recommendation for the use of classic Hayes-Martin maneuver to identify and preserve the MMN in cases of node-negative neck dissections (Figs. 12 and 13).

Relation to the lower border of the mandible

Nelson and Gingrass [35] reported MMN to course below the lower mandibular border in almost 100% cases. They argued that the contrasting results could be attributed to the differences in nerve location in fresh cadaver specimens and clinical practice, in comparison to embalmed cadaver specimens. Savary et al. [36] described that MMN is below the inferior border in relation to the facial artery. Their observations concluded that MMN lies below the mandibular border in 63% cases posterior to facial artery and 27% cases anterior to it. They also proposed that incision placed about 3–4 cm below mandible is safer to avoid nerve damage.

Baker and Conley [37] concluded based on clinical observations during parotidectomies, that the MMN is 1–2 cm below the lower border in almost all the cases and up to 3–4 cm below the lower border in patients with atrophic and lax tissues. They explained this disparity based on the extension of fascia during the rotation of the head to the contralateral side in surgical dissections. This observation is supported by Nason et al. [4] who concluded that the extension of the neck displaces the nerve downward and anteriorly and the lowest point of the nerve is 1.25 ± 0.7 cm inferior to the mandibular margin between the anterior and posterior facial veins based on neck dissections in 133 patients. Based on this concept and considering that the nerve mostly passes below the mandible and is always in the subplatysmal plane, we recommend supra-platysmal dissection of flap till the mandibular lower border and creating a pouch by opening the platysma-SMAS in the area of interest to decrease the chance of nerve injury (Figs. 18, 19, and 20).

Classical description by Dingman and Grabb [20] implies nerve injury can be avoided by placing incisions 2 cm below inferior mandibular margin but on the contrast abovementioned clinical dissection, studies [4, 37] concluded that nerve is at greater risk when the incision is placed 2 cm below the inferior mandibular margin. Marcuzzo et al. [10] concluded after their systematic meta-analysis that the prevalence of one MMN branch being below the margin of the mandible is 39% and this finding is of great significance while placing submandibular incision. We recommend placing the incision in the submandibular crease with caution, considering that the position of nerve inevitably changes with rotation of the neck and pull of the deep cervical fascia.

During surgeries above inferior mandibular margin anterior to the facial vessels, the dissection is advanced from the margin of mandible beneath the platysma supra-periosteally, to avoid the MMN as it lies within the platysma muscle immediately anterior to facial vessels [31]. The MMN lies beneath the deep fascia in this region and hence the dissection plane is established in subplatysmal tissue, reflecting the platysma away from the deep cervical fascia till the inferior mandibular margin, thus maintaining a tissue bridge that protects the nerve from iatrogenic injuries [15]. Based on this, we recommend sandwich technique using a submandibular fascia flap approach in primary submandibular gland surgery (Figs. 1, 2, and 3) and the superficial layer of deep fascia approach in re-operative cases assuming that the nerve is sandwiched and protected between the platysma muscle and deep fascia (Figs. 4, 5, and 6).

Relation to number of branches/anastomosis

Marginal mandibular nerve gives numerous branches towards the nerve end (Fig. 25). This was confirmed by Batra et al. [13] as they concluded that MMN showed more branches at termination (84%) than in its origin and course. They also reported that the nerve shows anastomosis with buccal branch of facial nerve in 12% cases and with mental nerve in 28% cases based on their cadaver dissection study. Woltmann et al. [38] reported anastomosis of MMN with the buccal branch of the facial nerve (42.22%), cervical branch of the facial nerve (22.22%), and no anastomosis (33.55%). Anatomical dissections by Toure et al. [39] have shown nerve connections with buccal and mental branches of the mandibular nerve which coordinate movements of the lower lip and, when injured, may result in spasms and functional synkinesia. The instance of lower lip paralysis is limited due to the variability in branching and anastomosis pattern of MMN with other nerves or its own branches [12, 36] (Table 1). Meta-analysis reports [10] conclude that the MMN more often manifests with single or double branches with a prevalence of 35% and shows most frequent anastomosis with the buccal branch of the facial nerve (20%) and more rarely anastomosis with mental nerve (12%), cervical branch of the facial nerve (5%), great auricular nerve (2%), transverse cervical nerve (2%), cervical (5%), and zygomatic branch (1%) of the facial nerve. De Bonnecaze et al. [40] performed anatomical dissection studies to report the variation in the innervation of facial muscles and distribution of communications with the facial nerve. They concluded that the MMN showed fewer communicating branches in comparison to other facial nerve branches and commented that the lower lip muscles displayed the least supplemental innervation by MMN. Hence, localization and protection of the nerve and its branches play a pivotal role in comprehensive patient management.

Anatomic references and landmarks for nerve localization

Many authors have given several anatomic references and measurements for the localization of MMN and its branches during surgical procedures (Tables 2 and 3). Rossell-Perry et al. [41] outlined the “Marginal branch triangle” limited by the anterior border platysma muscle, base of the mastoid apophysis, and superiorly by the lateral labial commissure. Gulses et al. [42] proposed a triangular area of “safety zone” for nerve preservation defined by Trago-basal line, cantho-gonial line, and line on the border of the mandible; whereas, Yang et al. [27] identified inferior border of the mandible in submental area 4.5 cm anterior to gonion as surgically safe.

However, these studies have rarely described the spatial trajectory of the nerve in three dimensions and henceforth the exact location of the nerve from palpable or visible landmarks can be highly variable [19].

Preoperative percutaneous mandibular marginal branch mapping and continuous intraoperative nerve monitoring reported by Lin et al. [22] concluded that there are reduced accidental nerve injuries due to more accurate identification and preservation during surgical procedures.

Although the precise location of the nerve and its branches is variable, the knowledge about its relationship in soft tissue relative to fascial planes helps the surgeon to determine appropriate depth and plane of dissection to protect the nerve from iatrogenic injuries [19]. Hence, the surgical technique becomes a crucial factor in nerve preservation [43].

Despite these considerations, nerve injuries are common during orofacial surgical procedures. Several studies in the past have aimed at analyzing the functionality of MMN following head and neck surgeries [4, 30]. Møller et al. [30] assessed the immediate postoperative and the frequency of permanent nerve damage in 159 patients undergoing level IB and IIA neck dissections. They reported 14% cases with lower lip malfunction after 2 weeks of surgery, and a 2-year follow-up the finding of 4–7% cases with permanent lip paralysis following level IB neck dissections. Further, they concluded that there was no reported case of the functional defect following level IIA neck dissections. Nason et al. [4] studied the nerve damage in patients in which nerve is visualized and sacrificed for oncological reasons and compared the findings with patients where the nerve was intended to be preserved. They concluded that among cases with preserved nerve, nerve praxia was present in 29% cases immediate post-operatively and persisted in 16% cases. They also reported that the visualization of nerve did not have a significant effect on the postoperative functionality of the nerve and commented that the incidence of nerve damage was higher in cases of neck dissections followed by radiotherapy.

Management of nerve palsy can be broadly categorized as restorative techniques and reconstructive techniques. Restorative techniques aim at restoring facial symmetry by myotomy or myomectomy of the elevator muscles of the paralytic side or the depressors of the normal side and neurolysis of MMN on the unaffected side [44]. Butler et al. [45] compared the patient satisfaction following treatment of MMN palsy with botulinum toxin and anterior belly of the digastric transfer. They concluded that the anterior belly of digastric transfer is a more permanent and satisfactory solution compared to botulinum toxin therapy. Other reconstructive techniques such as stylohyoid muscle transfer [46] and platysma motor nerve transfer [26] have been discussed in previous studies. Zhai et al. [47] proposed the use of upper buccal or cervical branches to correct marginal mandibular nerve defects and argued that this technique showed better functional results in comparison to greater auricular nerve graft or hypoglossal nerve anastomosis in the reconstruction of facial nerve defects.

Conclusion

MMN injury has both esthetic and functional implications for the patient. It is essential to understand the probable anatomical course and branches of the nerve, landmarks used to isolate the nerve, and strategize surgical approaches aimed deliberately to protect the nerve and avert the repercussions of nerve damage. In this article, various surgical techniques have been discussed in view of the abovementioned considerations to preserve the MMN from iatrogenic injuries during orofacial surgical procedures, which have proven to be highly beneficial in our clinical practice.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets during and/or analyzed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- MMN:

-

Marginal mandibular nerve

- SMAS:

-

Superficial musculo-aponeurotic system

- AFV:

-

Anterior facial vein

References

Hald J, Andreasson UK (1994) Submandibular gland excision: short and long-term complications. ORL 56(2):87–91. https://doi.org/10.1159/000276616

Ichimura K, Nibu KI, Tanaka T (1997) Nerve paralysis after surgery in the submandibular triangle: review of University of Tokyo Hospital experience. Head Neck 19(1):48–53. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1097-0347(199701)19:1<48::AID-HED9>3.0.CO;2-V

Smith WP, Peters WJ, Markus AF (1993) Submandibular gland surgery: an audit of clinical findings, pathology and postoperative morbidity. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 75(3):164–167

Nason RW, Binahmed A, Torchia MG, Thliversis J (2007) Clinical observations of the anatomy and function of the marginal mandibular nerve. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 36(8):712–715. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijom.2007.02.011

Batstone MD, Scott B, Lowe D, Rogers SN (2009) Marginal mandibular nerve injury during neck dissection and its impact on patient perception of appearance. Head Neck

Potgieter W, Meiring JH, Boon JM, Pretorius E, Pretorius JP (2005) Mandibular landmarks as an aid in minimizing injury to the marginal mandibular branch : a metric and geometric anatomical study, vol 178, p 171

Moffat DA, Ramsden RT (1977) The deformity produced by a palsy of the marginal mandibular branch of the facial nerve. J Laryngol Otol 91(5):401–406. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022215100083869

Tulley P, Webb A, Chana JS, Tan ST, Hudson D, Grobbelaar AO, Harrison DH (2000) Paralysis of the marginal mandibular branch of the facial nerve: treatment options. Br J Plast Surg 53(5):378–385. https://doi.org/10.1054/bjps.2000.3318

Hazani R, Chowdhry S, Mowlavi A, Wilhelmi BJ (2011) Bony anatomic landmarks to avoid injury to the marginal mandibular nerve. Aesthetic Surg J 31(3):286–289. https://doi.org/10.1177/1090820X11398352

Marcuzzo AV, Uran-brunelli ANŠ, Cin EDAL, Rigo S, Piccinato A, Nata FB, Tofanelli M, Boscolo-rizzo P, Grill V, Lenarda RDI, Tirelli G (2020) Surgical anatomy of the marginal mandibular nerve: a systematic review and meta-analysis, vol 750, p 739

Ghumman NU, FDS R, Yasser F, Phil M (2014) Marginal mandibular nerve and its relation with lower border of mandible and facial artery, vol 34, p 11

Khanfour AA, Metwally ESAM (2014) Marginal mandibular branch of the facial nerve: an anatomical study. Alexandria J Med 50(2):131–138. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajme.2013.12.004

Batra APS, Mahajan A, Gupta K (2010) Marginal mandibular branch of the facial nerve: an anatomical study. Indian J Plast Surg 43(1):60–64. https://doi.org/10.4103/0970-0358.63968

Sorenson E, Chesnut C (2018) Marginal mandibular versus pseudo-narginal nandibular nerve injury with submandibular deoxycholic acid injection. Dermatol Surg 44(5):733–735. https://doi.org/10.1097/DSS.0000000000001291

Owsley JQ, Agarwal CA (2008) Safely navigating around the facial nerve in three dimensions. Clin Plast Surg 35(4):469–477. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cps.2008.05.011

Balagopal PG, George NA, Sebastian P (2012) Anatomic variations of the marginal mandibular nerve. Indian J Surg Oncol 3(1):8–11. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13193-011-0121-3

Huettner F, Rueda S, Ozturk CN, Ozturk C, Drake R, Langevin CJ, Zins JE (2015) The relationship of the marginal mandibular nerve to the mandibular osseocutaneous ligament and lesser ligaments of the lower face. Aesthetic Surg J 35(2):111–120. https://doi.org/10.1093/asj/sju054

Seckel B: Facial danger zones: avoiding nerve injury in facial plastic surgery. Plast Surg, 1994.

Roostaeian J, Rohrich RJ, Stuzin JM (2015) Anatomical considerations to prevent facial nerve injury. Plast Reconstr Surg 135(5):1318–1327. https://doi.org/10.1097/PRS.0000000000001244

Dingman RO, Grabb WC (1962) Surgical anatomy of the mandibular ramus of the facial nerve based on the dissection of 100 facial halves. Plast Reconstr Surg 29(3):266–272. https://doi.org/10.1097/00006534-196203000-00005

Wang TM, Lin CL, Kuo KJ, Shih C (1991) Surgical anatomy of the mandibular ramus of the facial nerve in Chinese adults. Cells Tissues Organs 142(2):126–131. https://doi.org/10.1159/000147176

Lin B, Lu X, Shan X, Zhang L, Cai Z (2015) Preoperative percutaneous nerve mapping of the mandibular marginal branch of the facial nerve. J Craniofac Surg 26(2):411–414. https://doi.org/10.1097/SCS.0000000000001408

Davies JC, Ravichandiran M, Agur AM, Fattah A (2016) Evaluation of clinically relevant landmarks of the marginal mandibular branch of the facial nerve: a three-dimensional study with application to avoiding facial nerve palsy. Clin Anat 29(2):151–156. https://doi.org/10.1002/ca.22570

Al-Qahtani K, Mlynarek A, Adamis J, Harris J, Seikaly H, Islam T (2015) Intraoperative localization of the marginal mandibular nerve: a landmark study. BMC Res Notes 8:1

Murthy SP, Paderno A, Balasubramanian D (2019) Management of the marginal mandibular nerve during and after neck dissection. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 27(2):104–109. https://doi.org/10.1097/MOO.0000000000000523

Rodriguez-Lorenzo A, Jensson D, Weninger WJ, Schmid M, Meng S, Tzou CHJ (2016) Platysma motor nerve transfer for restoring marginal mandibular nerve function. Plast Reconstr Surg - Glob Open 4:1

Yang HM, Kim HJ, Park HW, Sohn HJ, Ok HT, Moon JH, Woo SH (2016) Revisiting the topographic anatomy of the marginal mandibular branch of facial nerve relating to the surgical approach. Aesthetic Surg J 36(9):977–982. https://doi.org/10.1093/asj/sjw045

Tirelli G, Bergamini PR, Scardoni A, Gatto A, Boscolo Nata F, Marcuzzo AV (2018) Intraoperative monitoring of marginal mandibular nerve during neck dissection. Head Neck 40(5):1016–1023. https://doi.org/10.1002/hed.25078

Lim YC, Lee JS, Choi EC (2006) Perifacial lymph node metastasis in the submandibular triangle of patients with oral and oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma with clinically node-positive neck. Laryngoscope

Møller MN, Sørensen CH (2012) Risk of marginal mandibular nerve injury in neck dissection. Eur Arch Oto-Rhino-Laryngology

Stern SJ (1992) Anatomic correlates of head and neck surgery: precise localization of the marginal mandibular nerve during neck dissection. Head Neck 14(4):328–331. https://doi.org/10.1002/hed.2880140414

Palkar VM (1997) Protection of marginal mandibular nerve during neck dissection. J Surg Oncol 66(1):54. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1096-9098(199709)66:1<54::AID-JSO11>3.0.CO;2-O

Shuaib Zaidi SM (2007) A simple nerve dissecting technique for identification of marginal mandibular nerve in radical neck dissection. J Surg Oncol 96(1):71–72. https://doi.org/10.1002/jso.20761

Tirelli G, Marcuzzo AV (2018) Lymph nodes of the perimandibular area and the hazard of the Hayes Martin maneuver in neck dissection. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg (United States) 159:692

Nelson DW, Gingrass RP (1979) Anatomy of the mandibular branches of the facial nerve. Plast Reconstr Surg 64(4):479–482. https://doi.org/10.1097/00006534-197910000-00006

Savary V, Robert R, Rogez JM, Armstrong O, Leborgne J (1997) The mandibular marginal ramus of the facial nerve: an anatomic and clinical study. Surg Radiol Anat 19(2):69–72. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01628127

Baker DC, Conley J (1979) Avoiding facial nerve injuries in rhytidectomy anatomical variations and pitfalls. Plast Reconstr Surg 64(6):781–795. https://doi.org/10.1097/00006534-197912000-00005

Woltmann M, De Faveri R, Sgrott EA (2006) Anatomosurgical study of the marginal mandibular branch of the facial nerve for submandibular surgical approach. Braz Dent J 17(1):71–74. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0103-64402006000100016

Toure G (2019) Tran De Fremicourt MK, Randriamanantena T, Vlavonou S, Priano V, Vacher C: Vascular and nerve relations of the marginal mandibular nerve of the face: anatomy and clinical relevance. Plast Reconstr Surg 143(3):888–899. https://doi.org/10.1097/PRS.0000000000005360

De Bonnecaze G, Vergez S, Chaput B, Vairel B, Serrano E, Chantalat E, Chaynes P (2019) Variability in facial-muscle innervation: a comparative study based on electrostimulation and anatomical dissection. Clin Anat 32(2):169–175. https://doi.org/10.1002/ca.23081. Epub 2018 Nov 26

Rossell-Perry P (2016) The marginal branch triangle: anatomic reference for its location and preservation during cosmetic surgery. J Plast Reconstr Aesthetic Surg 69(3):387–394. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bjps.2015.10.028

Gulses A, Kilic C, Sencimen M (2012) Determination of a safety zone for transbuccal trocar placement: an anatomical study. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 41(8):930–933. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijom.2012.02.013

Horne SK, Gal TJ, Brennan JA (2007) Prevalence and patterns of intraoperative nerve monitoring for thyroidectomy. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 136(6):952–956. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.otohns.2007.02.011

Conley J, Baker DC, Selfe RW (1982) Paralysis of the mandibular branch of the Facial Nerve. Plast Reconstr Surg 70:569–577

Butler DP, Leckenby JI, Miranda BH, Grobbelaar AO (2015) Botulinum toxin therapy versus anterior belly of digastric transfer in the management of marginal mandibular branch of the facial nerve palsy: a patient satisfaction survey. Arch Plast Surg 42(6):735–740. https://doi.org/10.5999/aps.2015.42.6.735

Ozturk MB, Ertekin C, Uzuneyupoglu O, Tezcan M (2018) Stylohyoid muscle transfer in marginal mandibular nerve palsy. J Craniofac Surg 29(8):E762. https://doi.org/10.1097/SCS.0000000000004739

Zhai QK, Wang XK, Tan XX, Lu L (2015) Reconstruction for facial nerve defects of zygomatic or marginal mandibular branches using upper buccal or cervical branches. J Craniofac Surg 26:245

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

No funding received.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AK constructed the framework of this article, including the data compilation, analysis, and exhibition. KB and MS helped in data compilation and were major contributors in writing the manuscript and tables. SP, LP, and SG contributed to writing the manuscript and photograph assimilation. The authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All procedures were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional ethics committee (IEC, KMC Manipal) and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Informed written consent to participate in the study was provided by all participants.

Consent for publication

Obtained. Images are entirely unidentifiable and there are no details on individuals reported within the manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kudva, A., Babu, K., Saha, M. et al. Marginal mandibular nerve — a wandering enigma and ways to tackle it. Egypt J Otolaryngol 37, 74 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s43163-021-00134-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s43163-021-00134-5