Abstract

Background

This study assesses the outcomes of total conservative parotidectomy in the management of benign parotid neoplasms. A retrospective review was conducted for all parotidectomies for benign superficial parotid neoplasms from 2013 to 2018. Facial nerve dysfunction, recurrence, and other side-effects were collected and statistically analyzed.

Results

A total of 21 patients were included in our study. Our series included a pleomorphic adenoma (16 patients), Warthin tumor (4 patients), and oncocytoma (1 patient). Overall, 12 patients had temporary facial nerve paresis (57.1%), 3 patients had temporary paralysis (14.3%)—no reported cases of permanent paralysis—and 6 patients sustained postoperative good facial nerve function (28.6%). No recurrence was reported in our study period. Other side effects included hemorrhage (1 patient), hematoma (2 patients), seroma (4 patients), and partial skin flap necrosis (2 patients). As well, Frey’s syndrome was reported in 11 patients, and most of them were managed conservatively.

Conclusions

Total conservative parotidectomy is a valuable approach for removing parotid tumors. The rate of complications after this procedure (facial nerve dysfunction and recurrence) is low provided that the technique was performed with meticulous care.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Three to 10% of head and neck tumors occur in salivary glands [1]. Tumors of the parotid gland constitute more than 75% of these neoplasms, and most of them are benign in nature. As well, pleomorphic adenoma is the most encountered benign neoplasm among them with 60–70% incidence [2]. However, surgical resection of benign parotid lesions remains challenging being double-edged by recurrence and significant risk of facial nerve injury [3].

In the 1940s, intracapsular enucleation was introduced as management for pleomorphic adenoma. Leaving the tumor capsule in situ resulted in 45% of recurrence. Patey and Thackray [4], also, explained that the capsule of the tumor is often incomplete, and therefore, a lumpectomy was suggested to be replaced by other procedures. Extracapsular dissection removes 2–3 mm rim of healthy tissue without dissection of the facial nerve, and partial superficial parotidectomy removes 2 cm of normal parotid tissue with partial facial nerve dissection. Still, both modalities faced the same disadvantages of lumpectomy—the risk of facial nerve trunk injury and up to 25% recurrence—and thus are no more recommended [5, 6].

Removal of superficial lobe of parotid gland (superficial parotidectomy) (SP) or total removal of the parotid gland with facial nerve-sparing (total conservative parotidectomy) (TCP) provides good alternatives for benign parotid tumor neoplasm resections with merits of facial nerve preservation, substantial decrease in recurrence rates, and almost hundred percent healing [7]. Furthermore, SP versus TCP carries the advantages of avoiding postoperative temporary facial nerve weakness and Frey’s syndrome. However, there is evidence that 60% of parotid tumors lie in close contact with facial nerve, and so, exposure of tumor capsule remains a great concern [3]. This retrospective study assesses the immediate and long-term results of TCP in patients with benign parotid neoplasms.

Methods

This study was conducted at university hospital after ethical approval from institutional review board, and we reviewed retrospectively all parotidectomies for benign parotid neoplasms from 2013 to 2018. All patients signed a prior informed consent for the surgical intervention.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

We included all adult patients (> 18 years old) who underwent TCP for parotid neoplasms. Lesions in this study were limited to primary parotid tumors according to the 2017 World Health Organization classification [8]. Tumors had to be benign as shown by fine-needle aspiration and including the deep lobe of the parotid gland. All surgeries were performed by the study authors. Only lesions that were pathologically confirmed were included. We also excluded patients with recurrent neoplasms or history of a previous operation on the affected parotid gland.

The operative technique

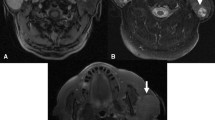

General anesthesia with short-acting smooth muscle relaxant was used for intubation. Patients were positioned with hyperextended head and face turned to the opposite side. Corners of the eye and mouth were kept exposed as a monitor for facial movements. We used modified Blaire incision with skin flap raised superficial to parotid fascia and neck flap raised deep to the platysma. Posteriorly, flap was deepened to sternomastoid muscle. Facial nerve trunk was identified through the tragal pointer, level of the posterior belly of the digastric muscle, and tympano-mastoid suture. All of the facial nerve branches were, then, followed, dissected, and mobilized. The deep parotid tissue was then removed between these branches. Autologous abdominal fat was used for reconstruction to fill the defect after TCP. A drain was left for at least 48 h (Fig. 1).

This figure depicts 70-year-old male with left parotid mass measuring 2.1 × 1.7 cm with parapharyngeal extension as shown in MRI neck with contrast (top left), identification of facial nerve trunk and branches was done (top right), then total conservative parotidectomy was done (bottom left), and drain was inserted for 48 h (bottom right)

Outcome measures and statistical analysis

Immediate postoperative facial nerve dysfunction and long-term results (which were assessed after 6 months; Frey’s syndrome, neuroma, and keloid formation) of TCP were our primary outcome. Recurrence was assessed after 1 year of operation. We also extracted age, sex, pathological diagnosis, lesion site, size, and laterality. All data analysis was performed using R software version 3.4.4 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) [9]. Our figures were generated using R package “ggplot2” [10].

Results

A total of 21 patients met our inclusion criteria in the study period, 2013–2018. Most of them (67.2%) were female (16 patients). Most neoplasms occurred mainly in the 40–49 age group (8 patients, 38%). Lesions involved the parotid tail (52.4% in 11 patients), body (33.3% in 7 patients), and both body and tail (14.3% in 3 patients) with sizes ranging between 2 and 6 cm. Our series included a pleomorphic adenoma (16 patients, 76.2%), Warthin tumor (4 patients, 19%), and oncocytoma (1 patient, 4.8%) as shown in (Table 1).

Outcomes of TCP

Short-term outcomes included primary hemorrhage (1 patient, 4.8%), hematoma (2 patients, 9.5%), seroma (4 patients, 19%), and partial skin flap necrosis (2 patients, 9.5%). Exploration of the hemorrhage case was done, and cauterization of the bleeding vessel was done. Hematoma and seroma were managed by aspiration of the accumulated fluid. Skin flap necrosis occurred in the very distal end of the post-auricular flap.

Overall, 12 patients had temporary facial nerve paresis (57.1%), 3 patients had temporary paralysis (14.3%), there were no reported cases of permanent paralysis, and 6 patients sustained post-operative good facial nerve function (28.6%). House Brackman grade in the temporary paralysis group was 3 for two patients and 4 for one patient. All patients who had temporary facial nerve dysfunction regained good facial movements over 6 months of follow-up.

Long-term outcomes included the presence of Frey’s syndrome in 11 patients (52.4%), neuroma in 2 patients (9.5%), and keloid in 4 patients (19%). Majority of patients with Frey’s syndrome were satisfied with the explanation of condition and re-assurance. No recurrence was reported in our study period.

Discussion

Twenty-one cases of TCP were identified in our study. No facial nerve dysfunction in the form of permanent paresis or paralysis occurred. As well, these results together with the absence of other serious side effects demonstrate the authors’ philosophy for using this special technique as a primary modality of treatment for parotid neoplasms.

Parotid surgeons have to find a compromise/strike a balance between recurrence and facial nerve dysfunction. Almost 20–45% of recurrence follows tumor enucleation [11]. Some authors advocated the use of postoperative radiation to decrease the recurrence, especially in multi-nodular pleomorphic tumors [12]. However, the use of routine radiotherapy as an initial modality for benign parotid neoplasms are arguable. Therefore, parotidectomy with facial nerve-sparing is preferred. Superficial parotidectomy might exhibit a good alternative for enucleation, but recurrence rates are still reported [13]. TCP provides the least reported rates of recurrence after 15 years of follow-up without the use of postoperative radiation [14].

Others argued that treatment of parotid neoplasms should be individualized according to the site of neoplasm and suggested that TCP added no more benefit versus SP. Furthermore, recurrence after parotidectomy is multifactorial linked to positive margin, tumor spillage, and satellite nodules. Furthermore, if the tumor was in direct contact with the facial nerve, both SP and TCP might leave microscopic metastasis and then sacrificing of the involved branch is mandatory to avoid recurrence. In spite of all of the previous concerns, we here specifically raise our concern that TCP had least reported rates of recurrence but also scarring after previous parotid surgery makes facial nerve injury during revision surgeries much more common. Moreover, some surgeons blame recurrence on the inadequate resection so TCP would be a more appropriate initial procedure.

Our results, as well, depicted no permanent facial nerve palsy. Although this might be less than the reported incidence in literature, it can be easily obtained through meticulous dissection and good training. As well, facial nerve outcomes similar to ours were obtained in previous reports [15]. Other types of complications after TCP had insignificant morbidity.

Our study might have various limitations, firstly being non-comparative and, secondly, the limited number of included patients. However, we provided a relatively longer period of follow-up with standardized management protocol and detailed reporting of other side effects.

Conclusion

TCP is a valuable approach for removing parotid tumors. It avoids the difficult facial nerve dissection in case of recurrent tumors. To master this technique, adequate training is needed with proper guidance. The rate of complications after this procedure is low provided that the technique was performed with meticulous care.

Availability of data and materials

Available upon request

Abbreviations

- SP:

-

Superficial parotidectomy

- TCP:

-

Total conservative parotidectomy

References

Ellis GL, Auclair PL (1996) Tumors of the salivary glands. Armed Forces Institute of Pathology. Atlas of Tumor Pathology, Washington, DC

Langton J (2011) Salivary and thyroid surgery: parotid surgery, in operative oral and maxillofacial surgery (Hodder Arnold, ed). Hodder Edi, London, UK

Witt RL (2002) The significance of the margin in parotid surgery for pleomorphic adenoma. Laryngoscope 112:2141–2154

Patey DH, Thackray AC (1958) The treatment of parotid tumours in the light of a pathological study of parotidectomy material. Br J Surg 45:477–487

Piekarski J, Nejc D, Szymczak W, Wronski K, Jeziorski A (2004) Results of extracapsular dissection of pleomorphic adenoma of parotid gland. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 62:1198–1202

Emodi O, El-Naaj IA, Gordin A, Akrish S, Peled M (2010) Superficial parotidectomy versus retrograde partial superficial parotidectomy in treating benign salivary gland tumor (pleomorphic adenoma). J Oral Maxillofac Surg 68:2092–2098

Čaušević Vučak M, Mašić T (2014) The incidence of recurrent pleomorphic adenoma of the parotid gland in relation to the choice of surgical procedure. Med Glas (Zenica) 11:66–71

El-Naggar AK, Chan JKC, Grandis JR, Takata T, Slootweg PJ: WHO classification of head and neck tumours WHO Classification of Tumours, 4th Ed., Volume 9, 2017, IARC, Lyon.

R Core Team (2017). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. URL https://www.R-project.org/.

Wickham H. ggplot2: elegant graphics for data analysis. Springer; 2016.

Donovan DT, Conley JJ (1984) Capsular significance in parotid tumor surgery: reality and myths of lateral lobectomy. Laryngoscope 94:324–329

Park GC, Cho K-J, Kang J et al (2012) Relationship between histopathology of pleomorphic adenoma in the parotid gland and recurrence after superficial parotidectomy. J Surg Oncol 106:942–946

Guntinas-Lichius O, Kick C, Klussmann JP, Jungehuelsing M, Stennert E (2004) Pleomorphic adenoma of the parotid gland: a 13-year experience of consequent management by lateral or total parotidectomy. Eur Arch Oto-Rhino-Laryngology 261:143–146

Wittekindt C, Streubel K, Arnold G, Stennert E, Guntinas-Lichius O (2007) Recurrent pleomorphic adenoma of the parotid gland: analysis of 108 consecutive patients. Head Neck 29:822–828

Marchesi M, Biffoni M, Trinchi S, Turriziani V, Campana FP (2006) Facial nerve function after parotidectomy for neoplasms with deep localization. Surg Today 36:308–311

Acknowledgements

No

Funding

None

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

TAA, YAK, ME, and AAE were responsible for the idea, study design, and supervising the study. AHZ analyzed the data, and TAA, YAK, ME, and AAE wrote the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript and approved its final version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was conducted at Menoufia University Hospital after ethical approval from institutional review board, and we reviewed retrospectively all parotidectomies for benign parotid neoplasm from 2013 to 2018. All patients signed a prior informed consent.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent for publication of the patient’s details was obtained from the patient.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

El-Hafez, T.A.ER.A., Khalil, Y.A.EW., El Noaman, M. et al. Total conservative parotidectomy for management of benign parotid neoplasms. Egypt J Otolaryngol 36, 42 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s43163-020-00046-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s43163-020-00046-w