Abstract

Background

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy (LC) remains as the gold standard of surgical treatment for gallstone disease. Biliary duct injury (BDI) is an infrequent but serious complication of LC. Strasberg's critical view is a useful strategy to minimize the risk of a BDI. However, BDIs could still happen. Variations of the right posterior hepatic duct (RPHD) are common. The surgical treatment of RPHD injury is challenging and literature on this matter is scarce.

Case summary

Aberrant drainage of the right posterior hepatic duct (RPHD) into the gallbladder neck was unexpectedly identified in a 43-year-old man during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Intraoperative consultation with a specialized Hepatobiliary surgeon was accomplished and a laparoscopic anastomosis between the RPHD and the jejunum with a Roux-en-Y reconstruction was carried out. The operation was uneventful with no long-term complication reported over a 12-month follow-up period.

Conclusion

Aberrant implantation of the RPHD into the gallbladder neck must be borne in mind despite its low incidence. Previous studies reporting the management of this injury are scarce. In our case, a laparoscopic Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy with the RPHD by an experienced HPB surgeon was a successful strategy to solve this difficult case.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy (LC) is one of the most common abdominal surgical procedures performed worldwide and remains the gold standard for the surgical treatment of gallstone disease. Biliary duct injury (BDI) is an infrequent but serious complication of LC. Strasberg’s critical view is a proposed strategy to identify the cystic duct and artery in order to minimize the risk of a BDI [1]. However, variations in the biliary tree anatomy can be found in up to 47% of cases [2, 3]. Aberrant drainage of the right posterior hepatic duct (RPHD) on the cystic duct or gallbladder neck accounts for 5.8% of these variants [3] (Fig. 1). Management of an RPHD injury is challenging and literature on this matter is scarce. We report the case of an aberrant RPHD duct drainage into the neck of the gallbladder which was injured during LC, and its subsequent treatment.

Case presentation

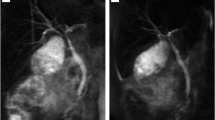

An otherwise healthy 43-year-old male presented a 1-week history of upper abdominal pain and jaundice. Abdominal ultrasound scan was performed and revealed a wall thickening and multiple gallbladder stones, without any signs of biliary tract obstruction. Blood tests showed direct hyperbilirubinemia and leukocytosis. A magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) was performed, showing no biliary tract obstruction or anatomic variations of the biliary tree (Fig. 2).

A laparoscopic cholecystectomy was planned. After the Calot triangle dissection, the surgeon interpreted that Strasberg's critical view of safety had been achieved. The cystic duct was clipped on its junction with the gallbladder neck. Then, a small incision was made below this point. A cholangiography catheter was inserted into the cystic duct and an IOC was performed. Even though there was no evidence of common bile duct filling defects, the surgical team was not able to identify the RPHD (Fig. 3). Despite this, the surgeon proceeded to transect the cystic duct with scissors (non-thermic), and another 5-mm tubular structure was found parallel to the cystic duct (Fig. 4). A new IOC was performed through this structure, revealing that this was in fact the RPHD (Fig. 5). Intraoperative consultation with a specialized Hepatobiliary surgeon was conducted and a laparoscopic Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy with the RPHD was carried out. Firstly, the jejunal limb was prepared by transecting the jejunum around 60 cm distal from the Treitz ligament and then was exteriorized through the umbilical port to perform the jejunal anastomosis externally. After that, a single-layer end-to-side running suture between the RPHD and the jejunal limb was performed with polypropylene 4/0. A suction drain was placed beneath the liver. The patient had an uneventful recovery and was discharged on postoperative day 4. Surgical drain was removed on postoperative day 6. After 12 months of follow-up, the patient remains asymptomatic and a MRPC performed did not reveal late anastomotic stricture.

Discussion

BDI incidence has risen 0.4% to 0.7% with LC compared to a 0.1% to 0.2% with open cholecystectomy [4]. Anatomic variations of the biliary tree, such as an aberrant implantation of the RPHD, increase the risk of bile duct injury as well [5].

Preoperative magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) imaging is a non-invasive technique that can be useful to detect anatomical variations of the biliary tract. A review has suggested that MRCP should be used to study the biliary anatomy preoperatively [6].

Another helpful imaging modality to study the biliary tree anatomy is intraoperative cholangiography (IOC), but its use for preventing BDI still remains controversial [7]. A review has shown no difference in the incidence of BDI whether IOC is used or not [8]. Conversely, other studies have reported a lower BDI rate in routine IOC (< 0.3%) compared to selective or no IOC (0.5%) [9]. Although a systematic review has detected no protective effect against BDI in either selective IOC or routine IOC groups, the latter diagnosed 79% of injuries in the operating room [10]. The reason for RPHD absence was that the cholangiography catheter had been inserted distal to the aberrant implantation of the RPHD in the gallbladder neck. As a result, the contrast liquid did not show the RPHD. After that, the big mistake was the underestimation of the presence of the RPHD by the surgeon, who then transected both the cystic and RPHD. After that, the IOC performed through the divided tubular structure to identify the injured RPHD.

Previous studies support the idea that intraoperative diagnosis of biliary tract injury and its repair are crucial for an optimal postoperative outcome [11]. Moreover, the outcome is considered significantly better if the repair is performed by an experienced surgeon [4, 12]. In a review of 88 patients [13] with BDI following laparoscopic surgery, only 17% of repairs performed by a non-tertiary level hepatobiliary surgeon were successful compared with 94% of those performed by a specialist, and the hospital stay was three times longer when managed by a non-specialist surgeon (78 days versus 222 days). Our case took place in a high-volume center, allowing us to consult, on-table, a specialized HPB surgeon.

The optimal surgical procedure for repairing any BDI should be determined by clinicians based on analysis of BDI type, biliary obstruction duration, previous biliary repair surgery history, degree of liver damage, and the patient's general condition [14]. However, the best surgical treatment for RPHD injury remains controversial as only a few case reports have been published in the literature so far. Multiple therapeutic strategies have been reported [12, 15, 16] but there is no clear consensus or algorithm for an optimal surgical management. There is one study that reports a resection of segments 6 and 7 of the liver, considering that it may be the optimal approach when the RPHD injury is too small or cannot be located [13]. In addition, a retrospective analysis describes an initial percutaneous management with placement of a transhepatic stent followed by a Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy to the isolated biliary segment [5]. For thermal biliary injury management, the literature describes that the affected segment must be resected back to healthy viable tissue due to damage to microcirculation. Furthermore, a Roux-en-Y Bilioenteric anastomosis should be performed [17]. The HPB surgeon in our team decided to reconstruct the injured RPHD with a Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy based on 3 reasons: acceptable diameter of the RPHD (5 mm), non-thermic biliary injury, and experience in laparoscopic bile reconstruction.

Conclusion

Aberrant implantation of the RPHD must be taken into consideration during a laparoscopic cholecystectomy despite its low incidence. Laparoscopic Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy with the RPHD could be a good option when local conditions are favorable and an experienced laparoscopic HPB surgeon is present in the operating room.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- LC:

-

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy

- BDI:

-

Biliary duct injury

- RPHD:

-

Right posterior hepatic duct

- MRCP:

-

Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography

- IOC:

-

Intraoperative cholangiography

- HPB:

-

Hepatobiliary

- RAHD:

-

Right anterior hepatic duct

- LHD:

-

Left hepatic duct

- CDH:

-

Common hepatic duct

- CBD:

-

Common bile duct

- CD:

-

Cystic duct

References

Montalvo-Javé EE, Contreras-Flores EH, Ayala-Moreno EA, Mercado MA (2022) Strasberg’s critical view: strategy for a safe laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Euroasian J Hepatogastroenterol. 12(1):40–44. https://doi.org/10.5005/jp-journals-10018-1353. (PMID: 35990864; PMCID: PMC9357518)

Bowen G, Hannan E, Harding T, Maguire D, Stafford AT (2021) Aberrant right posterior sectoral duct injury necessitating liver resection. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 103(8):e241–e243. https://doi.org/10.1308/rcsann.2020.7044. (PMID: 34464577)

Chaib E, Kanas AF, Galvão FH, D’Albuquerque LA (2014) Bile duct confluence: anatomic variations and its classification. Surg Radiol Anat 36(2):105–109. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00276-013-1157-6. (Epub 2013 Jul 2 PMID: 23817807)

Lau WY, Lai EC, Lau SH (2010) Management of bile duct injury after laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a review. ANZ J Surg 80(1–2):75–81. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1445-2197.2009.05205.x. (PMID: 20575884)

Lillemoe KD, Petrofski JA, Choti MA et al (2000) Isolated right segmental hepatic duct injury: a diagnostic and therapeutic challenge. J Gastrointest Surg 4:168–177. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1091-255X(00)80053-0

Rhaiem R, Piardi T, Renard Y, Chetboun M, Aghaei A, Hoeffel C, Sommacale D, Kianmanesh R (2019) Preoperative magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography before planned laparoscopic cholecystectomy: is it necessary? J Res Med Sci 23(24):107. https://doi.org/10.4103/jrms.JRMS_281_19.PMID:31949458;PMCID:PMC6950362

Chehade M, Kakala B, Sinclair JL, Pang T, Al Asady R, Richardson A, Pleass H, Lam V, Johnston E, Yuen L, Hollands M (2019) Intraoperative detection of aberrant biliary anatomy via intraoperative cholangiography during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. ANZ J Surg 89(7–8):889–894. https://doi.org/10.1111/ans.15267. (Epub 2019 May 13 PMID: 31083792)

Giger U, Ouaissi M, Schmitz SF, Krähenbühl S, Krähenbühl L (2011) Bile duct injury and use of cholangiography during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Br J Surg 98(3):391–396. https://doi.org/10.1002/bjs.7335. (Epub 2010 Nov 16 PMID: 21254014)

Alvarez FA, de Santibañes M, Palavecino M, Sánchez Clariá R, Mazza O, Arbues G, de Santibañes E, Pekolj J (2014) Impact of routine intraoperative cholangiography during laparoscopic cholecystectomy on bile duct injury. Br J Surg 101(6):677–684. https://doi.org/10.1002/bjs.9486. (Epub 2014 Mar 24 PMID: 24664658)

Kovács N, Németh D, Földi M, Nagy B, Bunduc S, Hegyi P, Bajor J, Müller KE, Vincze Á, Erőss B, Ábrahám S (2022) Selective intraoperative cholangiography should be considered over routine intraoperative cholangiography during cholecystectomy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Surg Endosc. 36(10):7126–7139. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-022-09267-x. (Epub 2022 Jul 7. PMID: 35794500; PMCID: PMC9485186)

Pesce A, Palmucci S, La Greca G, Puleo S (2019) Iatrogenic bile duct injury: impact and management challenges. Clin Exp Gastroenterol 6(12):121–128. https://doi.org/10.2147/CEG.S169492.PMID:30881079;PMCID:PMC6408920

Saad Nael, Darcy Michael (2008) Iatrogenic Bile Duct Injury During Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy. Tech Vasc Interv Radiol. 11(2):102–110. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.tvir.2008.07.004. (ISSN 1089-2516)

Stewart L, Way LW (1995) Bile duct injuries during laparoscopic cholecystectomy Factors that influence the results of treatment. Arch Surg. 130(10):1123–8. https://doi.org/10.1001/archsurg.1995.01430100101019. (PMID: 7575127 discussion 1129)

Feng X, Dong J (2017) Surgical management for bile duct injury. Biosci Trends 11(4):399–405. https://doi.org/10.5582/bst.2017.01176. (Epub 2017 Aug 19 PMID: 28824026)

Wojcicki M, Patkowski W, Chmurowicz T, Bialek A, Wiechowska-Kozlowska A, Stankiewicz R, Milkiewicz P, Krawczyk M (2013) Isolated right posterior bile duct injury following cholecystectomy: report of two cases. World J Gastroenterol 19(36):6118–6121. https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v19.i36.6118.PMID:24106416;PMCID:PMC3785637

Oyama, K., Nakahira, S., Ogawa, H. et al. Successful management of aberrant right hepatic duct during laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a rare case report. surg case rep 5, 74 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40792-019-0632-7

Holzheimer RG, Mannick JA, editors. Surgical Treatment: Evidence-Based and Problem-Oriented. Munich: Zuckschwerdt; 2001. PMID: 21028753.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable

Funding

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Not applicable.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

I state that the Sanatorio Güemes Ethical committee approved the respective study.

Consent for publication

I certify that an informed written consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this report and any accompanying images.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Rodriguez Zamboni, J.A., Ruiz Diaz, P., Peña, M.E. et al. Laparoscopic Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy as an acute treatment of a right posterior hepatic duct injury: a case report. Egypt Liver Journal 13, 36 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s43066-023-00272-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s43066-023-00272-w