Abstract

Background

Hypertension (HTN) is highly prevalent among people living with HIV (PLHIV), but there is limited access to standardized HTN management strategies in public primary healthcare facilities in Nigeria. The shortage of trained healthcare providers in Nigeria is an important contributor to the increased unmet need for HTN management among PLHIV. Evidence-based TAsk-Strengthening Strategies for HTN control (TASSH) have shown promise to address this gap in other resource-constrained settings. However, little is known regarding primary health care facilities’ capacity to implement this strategy. The objective of this study was to determine primary healthcare facilities’ readiness to implement TASSH among PLHIV in Nigeria.

Methods

This study was conducted with purposively selected healthcare providers at fifty-nine primary healthcare facilities in Akwa-Ibom State, Nigeria. Healthcare facility readiness data were measured using the Organizational Readiness to Change Assessment (ORCA) tool. ORCA is based on the Promoting Action on Research Implementation in Health Services (PARIHS) framework that identifies evidence, context, and facilitation as the key factors for effective knowledge translation. Quantitative data were analyzed using descriptive statistics (including mean ORCA subscales). We focused on the ORCA context domain, and responses were scored on a 5-point Likert scale, with 1 corresponding to disagree strongly.

Findings

Fifty-nine healthcare providers (mean age 45; standard deviation [SD]: 7.4, 88% female, 68% with technical training, 56% nurses, 56% with 1–5 years providing HIV care) participated in the study. Most healthcare providers provide care to 11–30 patients living with HIV per month in their health facility, with about 42% of providers reporting that they see between 1 and 10 patients with HTN each month. Overall, staff culture (mean 4.9 [0.4]), leadership support (mean 4.9 [0.4]), and measurement/evidence-assessment (mean 4.6 [0.5]) were the topped-scored ORCA subscales, while scores on facility resources (mean 3.6 [0.8]) were the lowest.

Conclusion

Findings show organizational support for innovation and the health providers at the participating health facilities. However, a concerted effort is needed to promote training capabilities and resources to deliver services within these primary healthcare facilities. These results are invaluable in developing future strategies to improve the integration, adoption, and sustainability of TASSH in primary healthcare facilities in Nigeria.

Trial registration

NCT05031819.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Find the latest articles, discoveries, and news in related topics.Introduction

Nigeria has a high burden of HIV and hypertension (HTN), with over a quarter of adults faced with a dual burden of hypertension and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) [1]. The declining prevalence of infectious diseases and the increase in cardiovascular diseases has resulted in an epidemiological transition, with implications for strengthening health systems [1]. Most health systems in low-income countries like Nigeria are often ill-prepared, with limited resources or capacity to effectively coordinate chronic care efforts to benefit patients [2]. HIV programs have successfully established longitudinal care models, focusing on continuity and retention, routine monitoring, and healthy lifestyle promotion [3]. However, it remains unknown whether these successful outcomes can be translated to improve the quality and efficiency of care among hypertensive PLHIV [3]. In a literature review of models for integrated service delivery, major challenges with integration included human resources, the supply chain for non-communicable diseases management, poor referral systems, limited patient education, poor records keeping, and monitoring and evaluation [4, 5]. As numerous efforts are underway to address the growing HTN burden among PLHIV, one important precursor to the successful implementation of interventions is organizational readiness for change.

Defined as the extent to which organizations are willing (motivation) and able (capacity) to implement change [6], organizational readiness is associated with implementation success [7]. It plays an important role during all phases of implementation, reflecting an organization’s overall commitment, motivation, and capacity for change over time [6, 7]. Specifically, during the pre-implementation phase, readiness can guide the selection of implementation strategies to suit a particular context and needs of a population [8]. It can also highlight an organization’s commitment and collective capability during and post-implementation. It also identifies critical areas of the health system to enable informed scale-up of integrated HIV and non-communicable disease care services for PLHIV. According to prior research, examining readiness can help to explain why some efforts to implement interventions succeed, while others fail [9,10,11]. Organizations with greater resources are more likely to have quality implementation [9, 12]. However, poor or limited readiness may lead to resistance and reduce the effectiveness of the implementation process [10, 13].

In the context of integrating hypertension care within HIV service delivery, the use of guideline-concordant practices requires preparation, motivation, and investment of time and resources [14]. Identifying potential obstacles may enable the tailoring of the intervention based on available resources [15]. While evidence-based approaches, such as task-strengthening (whereby specific duties are transferred to health workers with shorter training or fewer qualifications), thereby increasing their effectiveness, are well known for HTN management and care [16, 17], implementation of such approaches has been sub-optimal. To our knowledge, organizational readiness has not been considered to integrate evidence-based HTN interventions within HIV care in Nigeria using evidence-based task-strengthening approaches. Therefore, to increase the likelihood of successful adoption and maintenance of evidence-based nurse-led Task-Strengthening Strategy for HTN control (TASSH) within primary healthcare centers in Akwa-Ibom, Nigeria, the current study sought to identify gaps and highlight factors and/or barriers associated with organizational readiness with the integration of an evidence-based task-strengthening strategy within HIV care in Nigeria.

Methods

Study setting and participants

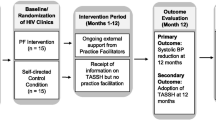

We conducted a descriptive, cross-sectional study of primary health centers (PHCs) across Akwa-Ibom state in the southern region of Nigeria. This study is a self-standing part of a larger implementation trial aiming to investigate the effectiveness of practice facilitation (PF) in integrating evidence-based TASSH for the management of HTN at PHCs serving PLHIV. TASSH includes identifying HIV patients with uncontrolled HTN, initiating lifestyle counseling and medication treatment, and referring patients with complicated HTN for further care. Components of the PF strategy include training the practice facilitators using a train-the-trainer model to identify PHC site champions and coordinators to provide support in implementing TASSH based on the Nigerian national guidelines for the management of HTN in PHCs [18], building consensus for quality improvement targets, implementation of practice changes to support TASSH implementation, and Peer-to-Peer collaboration.

TASSH has been successfully implemented across 32 community health centers in Ghana and led to 34% greater systolic blood pressure (BP) reduction than health insurance coverage alone [18, 19]. We purposively selected 59 primary healthcare facilities (Fig. 1) in Akwa-Ibom to reflect variations in the provision of comprehensive antiretroviral therapy (ART) services at the clinic sites, patient load, and facility type (private or public/government, or faith-based organizations), and primary facility level. Surveys were distributed to heads of health facilities and relevant outpatient departments such as outpatient, antenatal, family planning, child welfare, pharmacy, and laboratory. Survey distribution included efforts to reach the evening and night-shift employees and a representative sample of different types of providers. One response from each facility was provided. Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the University of Abuja Teaching Hospital Institutional Review Board. Written informed consent was obtained from the study participants.

Data collection

The study survey was conducted using interviewer-administered questionnaires with a secure web-based data capture (Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) software) [20]. The survey instrument included a short series of questions to assess the facility respondent's sociodemographic characteristics, including age, gender, the highest level of education, professional designation, and the number of years of providing HIV care, as well as the health facility characteristics, including the number of HIV patients seen per month, cost of HTN care, and Organizational Readiness to Change Assessment (ORCA) tool [21] to assess healthcare facility readiness [1] quantitatively. ORCA is based on the Promoting Action on Research Implementation in Health Services (PARIHS) framework and measures evidence, context, and facilitation as the critical factors for effective knowledge translation [22, 23]. The ORCA assesses aspects of an organization’s willingness to adopt intervention or new practices and the capability to implement change [24]. The tool consists of three scales (evidence, context, and facilitation) with multiple subscales developed to assess elements of the PARIHS framework. ORCA was selected given that it is theory-grounded and has been used and validated as part of several evidence-based efforts in health facilities [21, 25]. For the study, we focused on the context scale to assess the organizational readiness of health facilities in Akwa-Ibom, Nigeria, to integrate an evidence-based task-strengthening strategy within their HIV care centers. The context scale measures the research or practice environment and consists of six subscales assessing organizational culture, leadership, and measurement [26, 27].

Organizational culture refers to the values, beliefs, and attitudes shared by members of the organization [21, 26, 28]. Leadership includes elements of teamwork, control, decision-making, effectiveness of organizational structures, and issues related to empowerment [21, 26, 28]. Measurement relates to how the organization measures its performance and how (or whether) feedback is provided to people within the organization, as well as the quality of measurement and feedback [21, 26, 28]. Specifically, two sub-scales assess organizational culture, two sub-scales assess leadership practice, and one sub-scale assesses measurement or evaluation in terms of setting goals, and tracking and communicating performance. In addition, context includes a sub-scale that measures resources to support practice changes [21]. Participant’s responses to these subscales were scored on a 5-point Likert scale “Always,” “Sometimes,” “Rarely,” “Never,” and “Do not Know.”

Data analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to characterize all quantitative variables from the survey. Categorical variables were reported as frequencies and percentages. The ORCA responses were used to characterize health facility readiness. Mean and standard deviations of subscale scores were calculated among all study participants representing the health facilities. Scale and subscale scores are calculated by dividing the total score by the number of items on the scale, resulting in scores of 1 to 5. Higher scores demonstrate a more favorable attitude and reflect a greater readiness for change. Data management and statistical analysis were performed using the SAS System version 9.4 (SAS, Cary, NC, USA, 2016) [29].

Results

Study participants

Table 1 provides the sociodemographic characteristics of study participants. A total of 59 participants completed surveys; all healthcare professionals approached participated in our study with a mean age of 45 years (standard deviation [SD]: 7.4). The majority of the study participants were female, 52 (88%), and aged 35 years and older, 55 (93%). More than half of the participants, 33 (56%), were nurses, while the remaining consisted of physicians, 2 (3%), and other health professionals, 24 (41%). More than half of the participants, 33 (56%), had 1 to 5 years of experience providing HIV care.

Primary healthcare facilities’ characteristics

Among the 59 primary healthcare facilities evaluated, nearly half (48%, n = 28) reported serving 11–30 HIV patients per month. Over half, 33 (56%) of the health facilities reported not seeing HIV patients with HTN, while 25 (42%) reported seeing one to ten HIV patients with HTN. More than a third of the health facilities, 22 (37%), reported always having anti-HTN drugs in their facilities, while 20 (33.9%) reported rarely having antihypertensive drugs available. The 1-month consultation fee for treating HTN in over a third of 23 (39%) of the health facilities was reported to be of no cost, while it was between 100 and 900 Naira (equivalent to $0.25–$2.00) in another third, 19 (32.2%), of the health facilities. Only 2 (3%) of the health facilities provided antihypertensive drugs at no cost to their patients from ongoing intervention programs. Table 2 provides additional information on the characteristics of the participating primary healthcare facilities.

Participating health facilities’ readiness to implement TASSH: ORCA context scale

The ORCA context scales are summarized in Table 3. For each of the six subscales that make up the context scales (leadership culture, staff culture, leadership, measurement, opinion leaders, and resources), the mean scores were generally high, with 5/6 of the sub-scales having an average of 4.00 or higher. Leadership (mean [SD]: 4.57 [0.41]), staff culture (4.85 [0.42]), measurement or evidence-assessment (4.76 [0.46]), opinion leaders (4.67 [0.73]), and leadership culture (4.57 [0.63]) were the top-scored context subscales, while resources scored the lowest with a mean score of (3.59 [0.82]). Proportions related to the context scale are provided in Fig. 2.

Discussion

Our descriptive study utilized the ORCA tool to measure organizational readiness, particularly contextual factors for implementing TASSH in primary healthcare facilities in Akwa Ibom, Nigeria. This study adds to a growing body of research about organizational readiness for health practices and intervention integration into healthcare settings. Evaluating the context (culture and quality of the environment in which the intervention would be implemented) can improve the process and implementation outcomes [30] by identifying alignment areas and potential barriers. We encountered largely positive feedback on organizational readiness with several notable recommendations to facilitate PF in the integration of evidence-based TASSH for the management of HTN at PHCs serving PLHIV. Study participants perceived leadership, the organizational culture of staff members, and the measurement of evidence-based assessments as salient and conducive in their health facilities for the integration of TASSH. In contrast, resource scores had the lowest mean score and were less available for TASSH implementation [31].

Leadership and leadership culture indicators were largely positive and rated highly among study participants. Research has shown that leadership is an important contextual dimension [32, 33] and valuable in encouraging innovation and adoption of evidence-based interventions within organizations. Leadership support, motivation, and receptivity to innovations facilitate processes critical for implementation success [34, 35] by helping orchestrate decision processes from adoption to sustainability. The implementation strategy for TASSH integration within health facilities would involve working closely with health facility leaders to tailor approaches that best fit each context. Notably, although the overall mean score for leadership was relatively high, less than half of the participants agreed that their health facilities “always” reward clinical innovation and creativity for improvement. Further studies would be needed to elucidate preferences for rewards and how that is conceptualized by leadership and healthcare workers within organizations. Such evidence bolsters the demand for actively engaging key stakeholders to successfully integrate HTN/HIV services.

In addition, the influence of opinion leaders within the participating health facilities was scored highly. Opinion leaders are individuals who can influence the opinions, attitudes, beliefs, motivations, and behaviors of others [36]. Opinion leaders play a critical role in promoting the adoption of innovations and evidence-based interventions within organizations [37]. Opinion leaders, also known as “champions” in implementation science literature, play a crucial role in shaping organizational change by building organizational support for new practices and facilitating the growth of organizational coalitions in support of implementation [38,39,40]. To integrate TASSH within primary health facilities, the research team can tap into this opportunity by working with health facilities to identify opinion leaders or “champions” among the health providers. It is important to note that operating as an opinion leader to implement interventions within health facilities is a challenging and multifaceted role [40]. Therefore, adequate training and resources would be needed to ameliorate the additional burden associated with this tasking role.

Consistent with previous literature, the available resource subscale had the lowest ORCA mean score [31, 41]. In other studies in sub-Saharan Africa, lacking critical resources such as BP machines, medicines for HTN, and information on HTN/HIV integration hindered the successful integration of HTN care in HIV clinics [31, 42]. The lower scores for general resources suggest that many facilities may require additional staffing and financial resources to implement antihypertensive stewardship initiatives successfully. This underscores the need to adapt TASSH within the available resources while leveraging the strengths of the health facilities.

Our study collectively highlights several key contextual factors that can be leveraged to integrate practice facilitation and TASSH within health facilities in Nigeria. First, the study shows strong leadership support within the health facilities. Leadership buy-in is integral in the adoption and implementation of interventions. Second, we identified potential staff enthusiasm for the intervention implementation based on high scores on staff culture. This study provides a starting point for identifying favorable resources and opportunities for adopting TASSH and specific areas that may require targeted monitoring or assistance throughout the implementation cycle (pre-implementation and full-scale implementation) [29].

Strengths

Our study provides a systematic approach to engaging health facilities to determine readiness for intervention implementation. We achieved this by using ORCA, a valuable tool for healthcare organizations with evidence-based intervention implementation, identification of potential barriers, facilities, and opportunities for implementation, adoption, and ultimately sustainability.

Study limitations

However, our findings should be interpreted with caution, as the study design, including a sample of fifty-nine health facilities, limits generalizability to other primary health facilities in the State of Akwa Ibom, Nigeria. Nonetheless, we ensured that our sample was diverse regarding their occupation and involvement in the primary health facilities. Secondly, perspectives and practices are rapidly evolving across health facilities, given ever-changing inner and outer setting factors [43]. However, this study only focused on a one-time cross-sectional assessment. Thirdly, this study does not capture patient perspectives and all healthcare providers in the health facilities. In addition, there is a possibility for a potential responder bias about social desirability, perceived leadership, and resources given that the survey was interviewer-administered. It is possible that participants who were less engaged in the health facilities did not participate in the assessment, and, as a result, their perspectives were not captured.

Conclusions

There is a growing evidence base on the benefits of integrating HTN care within HIV clinics. Evaluating organizational readiness is a critical prerequisite for the tailored implementation of evidence-based interventions and practices [41]. Our study uses the ORCA tool for a systematic evaluation to understand the common barriers, facilitators, and opportunities for implementing TASSH within primary healthcare facilities, to optimize the chance of successful adoption and integration. Overall, findings show organizational support for innovation and the health providers at the participating health facilities. However, a concerted effort is needed to promote training capabilities and resources to deliver services within these primary healthcare facilities. These results are invaluable in developing future strategies to improve the integration, adoption, and sustainability of TASSH in primary healthcare facilities in Nigeria. Future implementation strategies for TASSH in Nigeria should consider these factors and tailor interventions accordingly.

Availability of data and materials

Data is available upon request to the corresponding author.

References

Odukoya O, Badejo O, Sodeinde K, Olubodun T. Behavioral risk factors for hypertension among adults living with HIV accessing care in secondary health facilities in Lagos State, Nigeria. J Fam Med Prim Care. 2020;9(7):3450.

Haldane V, Legido-Quigley H, Chuah FLH, Sigfrid L, Murphy G, Ong SE, Cervero-Liceras F, Watt N, Balabanova D, Hogarth S. Integrating cardiovascular diseases, hypertension, and diabetes with HIV services: a systematic review. AIDS Care. 2018;30(1):103–15.

Duffy M, Ojikutu B, Andrian S, Sohng E, Minior T, Hirschhorn LR. Non-communicable diseases and HIV care and treatment: models of integrated service delivery. Trop Med Int Health. 2017;22(8):926–37.

Kemp CG, Jarrett BA, Kwon C-S, Song L, Jetté N, Sapag JC, Bass J, Murray L, Rao D, Baral S. Implementation science and stigma reduction interventions in low-and middle-income countries: a systematic review. BMC Med. 2019;17(1):6.

Iwelunmor J, Ezechi O, Obiezu-Umeh C, Gbajabiamila T, Musa AZ, Oladele D, Idigbe I, Ohihoin A, Gyamfi J, Aifah A. Capabilities, opportunities and motivations for integrating evidence-based strategy for hypertension control into HIV clinics in Southwest Nigeria. PloS one. 2019;14(6):e0217703.

Domlyn AM, Wandersman A. Community coalition readiness for implementing something new: using a Delphi methodology. J Community Psychol. 2019;47(4):882–97.

Walker TJ, Brandt HM, Wandersman A, Scaccia J, Lamont A, Workman L, Dias E, Diamond PM, Craig DW, Fernandez ME. Development of a comprehensive measure of organizational readiness (motivation× capacity) for implementation: a study protocol. Implement Sci Commun. 2020;1(1):1–11.

Geerligs L, Shepherd H, Butow P, Shaw J, Masya L, Cuddy J, Rankin N. What factors influence organisational readiness for change? Implementation of the Australian clinical pathway for the screening, assessment and management of anxiety and depression in adult cancer patients (ADAPT CP). Support Care Cancer. 2021;29(6):3235–44.

Dariotis JK, Bumbarger BK, Duncan LG, Greenberg MT. How do implementation efforts relate to program adherence? Examining the role of organizational, implementer, and program factors. J Commun Psychol. 2008;36(6):744–60.

Vax S, Gidugu V, Farkas M, Drainoni M-L. Ready to roll: strategies and actions to enhance organizational readiness for implementation in community mental health. Implement Res Pract. 2021;2:2633489520988254.

Oetting ER, Jumper-Thurman P, Plested B, Edwards RW. Community readiness and health services. Subst Use Misuse. 2001;36(6–7):825–43.

Chu KWK, Cheung LLW. Incorporating sustainability in small health-care facilities: an integrated model. Leadership in health services (Bradford, England). 2018;31(4);441–51. https://doi.org/10.1108/LHS-07-2017-0043.

Wakida EK, Talib ZM, Akena D, Okello ES, Kinengyere A, Mindra A, Obua C. Barriers and facilitators to the integration of mental health services into primary health care: a systematic review. Syst Rev. 2018;7(1):1–13.

Kemp CG, Weiner BJ, Sherr KH, Kupfer LE, Cherutich PK, Wilson D, Geng EH, Wasserheit JN. Implementation science for integration of HIV and non-communicable disease services in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review. AIDS. 2018;32:S93–105.

Baker R, Camosso-Stefinovic J, Gillies C, Shaw EJ, Cheater F, Flottorp S, Robertson N, Wensing M, Fiander M, Eccles MP. Tailored interventions to address determinants of practice. Cochr Database Syst Rev. 2015;(4):CD005470.

Njuguna B, Vorkoper S, Patel P, Reid MJ, Vedanthan R, Pfaff C, Park PH, Fischer L, Laktabai J, Pastakia SD. Models of integration of HIV and noncommunicable disease care in sub-Saharan Africa: lessons learned and evidence gaps. AIDS (London, England). 2018;32(Suppl 1):S33.

Nyame S, Iwelunmor J, Ogedegbe G, Adjei KGA, Adjei K, Apusiga K, Gyamfi J, Asante KP, Plange-Rhule J. Capacity and readiness for implementing evidence-based task-strengthening strategies for hypertension control in Ghana: a cross-sectional study. Glob Heart. 2019;14(2):129–34.

Ogedegbe G, Plange-Rhule J, Gyamfi J, Chaplin W, Ntim M, Apusiga K, Iwelunmor J, Awudzi KY, Quakyi KN, Mogaverro J. Health insurance coverage with or without a nurse-led task shifting strategy for hypertension control: a pragmatic cluster randomized trial in Ghana. PLoS Med. 2018;15(5):e1002561.

Ogedegbe G, Plange-Rhule J, Gyamfi J, Chaplin W, Ntim M, Apusiga K, Khurshid K, Cooper R. A cluster-randomized trial of task shifting and blood pressure control in Ghana: study protocol. Implement Sci. 2014;9(1):73.

Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42(2):377–81.

Helfrich CD, Li Y-F, Sharp ND, Sales AE. Organizational readiness to change assessment (ORCA): development of an instrument based on the Promoting Action on Research in Health Services (PARIHS) framework. Implement Sci. 2009;4(1):1–13.

Kitson AL, Rycroft-Malone J, Harvey G, McCormack B, Seers K, Titchen A. Evaluating the successful implementation of evidence into practice using the PARiHS framework: theoretical and practical challenges. Implement Sci. 2008;3(1):1–12.

Rycroft-Malone J, Kitson A, Harvey G, McCormack B, Seers K, Titchen A, Estabrooks C. Ingredients for change: revisiting a conceptual framework. BMJ Qual Saf. 2002;11(2):174–80.

Hagedorn HJ, Heideman PW. The relationship between baseline Organizational Readiness to Change Assessment subscale scores and implementation of hepatitis prevention services in substance use disorders treatment clinics: a case study. Implement Sci. 2010;5(1):1–12.

Kononowech J, Hagedorn H, Hall C, Helfrich CD, Lambert-Kerzner AC, Miller SC, Sales AE, Damschroder L. Mapping the organizational readiness to change assessment to the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research. Implement Sci Commun. 2021;2(1):1–6.

McCormack B, Kitson A, Harvey G, Rycroft-Malone J, Titchen A, Seers K. Getting evidence into practice: the meaning ofcontext’. J Adv Nurs. 2002;38(1):94–104.

Rycroft-Malone J. The PARIHS framework—a framework for guiding the implementation of evidence-based practice. J Nurs Care Qual. 2004;19(4):297–304.

Rycroft-Malone J, Seers K, Titchen A, Harvey G, Kitson A, McCormack B. What counts as evidence in evidence-based practice? J Adv Nurs. 2004;47(1):81–90.

Version S. 9.4 of the SAS System for Windows. Cary: SAS Institute Inc 2013; 2016.

Damschroder LJ, Aron DC, Keith RE, Kirsh SR, Alexander JA, Lowery JC. Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: a consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implement Sci. 2009;4(1):50.

Muddu M, Tusubira AK, Nakirya B, Nalwoga R, Semitala FC, Akiteng AR, Schwartz JI, Ssinabulya I. Exploring barriers and facilitators to integrated hypertension-HIV management in Ugandan HIV clinics using the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR). Implement Sci Commun. 2020;1(1):1–14.

Durlak JA, DuPre EP. Implementation matters: a review of research on the influence of implementation on program outcomes and the factors affecting implementation. Am J Commun Psychol. 2008;41(3–4):327–50.

Stetler CB, Damschroder LJ, Helfrich CD, Hagedorn HJ. A guide for applying a revised version of the PARIHS framework for implementation. Implement Sci. 2011;6(1):1–10.

Aarons GA, Ehrhart MG, Farahnak LR, Sklar M. Aligning leadership across systems and organizations to develop a strategic climate for evidence-based practice implementation. Annu Rev Public Health. 2014;35:255–74.

Siehl C, Martin J. Organizational culture: a key to financial performance?: Graduate School of Business, Stanford University; 1989.

Rogers EM. Diffusion of innovations: Simon and Schuster; 2010.

Doumit G, Wright FC, Graham ID, Smith A, Grimshaw J. Opinion leaders and changes over time: a survey. Implement Sci. 2011;6(1):1–6.

Damschroder LJ, Banaszak-Holl J, Kowalski CP, Forman J, Saint S, Krein S. The role of the “champion” in infection prevention: results from a multisite qualitative study. BMJ Qual Saf. 2009;18(6):434–40.

Greenhalgh T, Robert G, Macfarlane F, Bate P, Kyriakidou O. Diffusion of innovations in service organizations: systematic review and recommendations. Milbank Q. 2004;82(4):581–629.

Holleman G, van Tol M, Schoonhoven L, Mintjes-de Groot J, van Achterberg T. Empowering nurses to handle the guideline implementation process: identification of implementation competencies. J Nurs Care Qual. 2014;29(3):E1–6.

Goebel MC, Trautner BW, Wang Y, Van JN, Dillon LM, Patel PK, Drekonja DM, Graber CJ, Shukla BS, Lichtenberger P. Organizational readiness assessment in acute and long-term care has important implications for antibiotic stewardship for asymptomatic bacteriuria. Am J Infect Control. 2020;48(11):1322–8.

Muddu M, Ssinabulya I, Kigozi SP, Ssennyonjo R, Ayebare F, Katwesigye R, Mbuliro M, Kimera I, Longenecker CT, Kamya MR. Hypertension care cascade at a large urban HIV clinic in Uganda: a mixed methods study using the Capability, Opportunity, Motivation for Behavior change (COM-B) model. Implement Sci Commun. 2021;2(1):1–16.

Hawk KF, D’Onofrio G, Chawarski MC, O’Connor PG, Cowan E, Lyons MS, Richardson L, Rothman RE, Whiteside LK, Owens PH. Barriers and facilitators to clinician readiness to provide emergency department–initiated buprenorphine. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(5):e204561–e204561.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the study participants for being part of this study.

Funding

This study is supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), award number 1UG3HL152381-01 under the Heart, Lung, and Blood Co-morbiditieS Implementation Models in People Living with HIV (HLB SIMPLe) program. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH. The study sponsor is the University of Abuja, Abuja, Nigeria.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Study concept and design: JI, OG, LD, DO. Data collection: HU, DO. Data analysis: HU. Drafting the manuscript: JI, UN, CO, DO. Critical revision of the manuscript: All authors [JI, OO, LD, AA, UN, CO, DO, AR, SM, CLC, EA, OB, KM, HU, GS, EMH, DH, AI, DL, GPB, DO]. The authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All procedures were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000. Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the University of Abuja Teaching Hospital Institutional Review Board and written informed consent was obtained from the study participants.

Consent for publication

This manuscript does not contain any identifiable data in any form, either at the organizational level or at the individual level.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Iwelunmor, J., Ogedegbe, G., Dulli, L. et al. Organizational readiness to implement task-strengthening strategy for hypertension management among people living with HIV in Nigeria. Implement Sci Commun 4, 47 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s43058-023-00425-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s43058-023-00425-3