Abstract

Background

The apolipoprotein A5 (APOA5) gene, significantly expressed in liver, has been involved in regulation of triglyceride metabolism, plasma lipid levels, serum adipokine levels and cardiovascular traits. A single-nucleotide polymorphism rs662799 ( − 1131A > G), 2 Kb upstream in the promoter region of this gene, causes decrease in the concentration of the product coded by this gene; hence, it may be responsible for impairments in normal function of the gene, ultimately leading to disease condition. Keeping in view the importance of APOA5 gene, the aim of the present study was to examine the association of genetic variant rs662799 of APOA5 gene with two quantitative traits simultaneously, viz. body mass index and blood pressure.

Results

The study involved a population of 246 subjects from North Indian region. Measurements of morphometric and physio-metric parameters were recorded using standard measures. Genotyping of APOA5 gene polymorphism (rs662799) using Tetra-primer amplification refractory mutation system PCR was performed. Statistical analyses were carried out using MS-Excel and SigmaPlot, and significance level was setup as p < 0.05. The allelic distribution of rs662799 polymorphism in this population was 77% for major allele (A) and 23% for minor allele (G). Significant association of rs662799 with increased body mass index and blood pressure was observed, with the presence of allele G. Under recessive genetic model, rs662799 polymorphism conferred a 17.71-fold risk of elevated body mass index (OR = 17.71, p < 0.001, CI (95%) = 4.05–77.46), and for increase in blood pressure, 3.79- and 3.83-fold risk of systolic blood pressure and diastolic blood pressure (OR = 3.792, p = 0.023, CI (95%) = 1.25–11.509 and OR = 3.83, p = 0.012, CI (95%) = 1.375–10.68, respectively) was observed. Under dominant genetic model, it showed a 3.060-fold risk of increase in body mass index (OR = 3.060, p < 0.001, CI (95%) = 1.78–5.25).

Conclusions

G allele of rs662799 of APOA5 gene showed significant susceptible association with BMI and BP. This study may be helpful for clinicians and researchers to investigate the diagnostic and prognostic value of the gene in question.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The apolipoprotein A5 (APOA5) gene (Chr-11q23) is among the most well-characterized member of the APOA1/C3/A4/A5 gene cluster which has been identified as a crucial regulator of metabolism of triglyceride (TG) and plasma lipid levels [1,2,3]. APOA5 consisting of four exons and three introns is translated into 366 amino acids long apolipoprotein A5 (APOA5) in liver exclusively and released in blood. It is associated with chylomicron, high-density lipoprotein (HDL), very low-density lipoprotein (VLDL), but not with low-density lipoprotein (LDL) [4]. Additionally, apolipoprotein plays the role of an activator of enzyme lipoprotein lipase and aids the clearance of TG from the circulation [5]. Different processes are involved in the mechanism of APOA5 affecting the metabolism of TGs; in particular, lipoprotein lipase causes this protein to decrease the production of VLDL triglycerides and enhance their hydrolysis [6]. The APOA5 gene has reportedly been linked in several studies to the development of the increased risk of metabolic syndrome [7,8,9] cardiovascular events [10], hypertriglyceridemia [11] and hyperchylomicronemia [12].

Among all reported variants in APOA5 gene, the rs662799 polymorphism ( − 1131A > G, promoter) has been extensively explored due to its association with higher levels of TG, total cholesterol, LDL cholesterol, lower levels of HDL cholesterol [4, 13, 14]. The HapMap database indicates that APOA5 rs662799 (A > G) has ethnic variations. The minor allele frequency in Japanese (HapMap-CHJ) populations is 28.9%, substantially higher than 26.7% as seen in Chinese population (HapMap-CHB), being 13.3% in people of African origin (HapMap-YRI) and lowest (1.7%) in European (HapMap-CEU) populations (HapMap-JPT) [9]. This genetic variant of the APOA5 gene has been designated to be a functional-tag SNV (single-nucleotide variant) [4, 15] and involved in lipid profile and metabolic syndrome [16]. The G allele of rs662799 deteriorates ribosomal translation efficiency which causes decrease in APOA5 concentrations and consequently decreases lipoprotein lipase activity [17, 18].

Obesity is an intricate disorder concerning an excessive amount of body fat that upsurges the risk of health complications. Recent studies have often looked at single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) variations within well-known genes, since there has been growing interest in the association between genes associated with obesity; among them one of the genes is APOA5 [19]. Despite its modest concentration in the plasma, it acts as a major determining factor of the metabolism and plasma level of TG, by reducing hepatic VLDL secretion and increasing its metabolism. Furthermore, the APOA5 gene variations in people of different ethnic groups affect plasma concentration of TG as well as the prevalence of obesity or metabolic syndrome [20]. Consistently, reduced plasma levels of APOA5 were discovered in obese individuals and were negatively linked with body mass index (BMI) in humans [21, 22], suggesting that lowered plasma levels of APOA5 may be coupled with the pathogenesis of obesity.

Hypertension, the complicated multifactorial condition results due to the interplay of genetic make-up and environmental factors. Genetic linkage analyses and candidate gene association studies have suggested that a number of loci and genes contribute to the tendency to hypertension; however, the genes that really confer vulnerability to this condition have not yet been discovered with certainty. There are ample of reports regarding the association of SNPs of APOA5 gene with cardiovascular disease, including carotid atherosclerosis [23], stroke [24] and coronary artery disease [3, 25, 26]. Hypertriglyceridemia is a major risk factor for both type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) and cardiovascular disease. A significant association between the APOA5 − 1131A/G polymorphism and the T2DM risk was found suggesting the G allele was independent risk factor for the progression of T2DM [27]. In Japanese population, the polymorphisms of APOA5 have been found to be implicated in blood pressure (BP) regulation and hypertension [28]. Several studies have reported the association of APOA5− 1131 A > G polymorphism to significantly higher systolic blood pressure (SBP), diastolic blood pressure (DBP), lipid levels and plasma TG among carriers of the − 1131G allele, which has been linked to an increased risk of coronary heart disease (CHD) and coronary artery disease (CAD) [29,30,31]. Experimental data indicate that persistent hypertriglyceridemia causes endothelial dysfunction, linked to a reduced capacity to respond to vasodilator stimulation and a subsequent drop in nitric oxide availability, both of which might contribute to elevated BP [30, 32].

A recent study suggests the role of rs662799 polymorphism of APOA5 gene in increasing the TG level as well as HDL, cholesterol and myocardial infarction [33]. Contemplating the association of this polymorphism with metabolic syndromes and cardiovascular events, it is logically plausible to hypothesize a link for the rs662799 polymorphism with morphometric and physio metric traits also. So, in the present study, we aimed to systematically investigate the association of the rs662799 polymorphism with body mass index (BMI) and blood pressure (BP) in North Indian population.

Methods

Study subjects and data collection:

The current study was carried out in two cities of Uttar Pradesh (North central zone of India), i.e., Aligarh (northWest district) and Ambedkar Nagar (northeast district). For this purpose, the survey was conducted from the month of August 2021–November 2021 and a total of 246 healthy subjects between the ages of 6 and 78 years were included. Those subjects were not recruited for the study, who were diseased or were not willing to participate. The parameters recorded from each participant were: morphometric data including height and weight, physio-metric data including systolic blood pressure (SBP), diastolic blood pressure (DBP) and pulse rate (PR).

To the nearest 0.1 kg and 0.5 cm, height and weight measurements, respectively, were acquired from subjects who were barefoot and wearing light clothes, by using standardized techniques. The body mass index (BMI) was calculated as per the weight (in kg) and height (in m2). Blood pressure (SBP and DBP) in mmHg and PR (bpm) were measured three times by using “Omron 8712 Automatic Blood Pressure Monitor” after at least 5–10 min of rest period, and average of 3 readings was employed in the analysis. Pulse pressure (PP in mmHg) and mean arterial pressure (MAP in mmHg) were computed using the formulae, \(\mathrm{PP}=(\mathrm{SBP}-\mathrm{DBP})\) and \(\mathrm{MAP}=\mathrm{DBP}+ \frac{1}{3}(\mathrm{SBP}-\mathrm{DBP})\), respectively.

Sample collection and DNA isolation:

Blood sample (3 ml) was taken from all the subjects by venepuncture from the median cubital vein using a syringe and collected in EDTA (ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid disodium salt)-coated vacutainers. DNA isolation was carried out for the samples using CTAB extraction method [34] and isolated DNA was maintained at − 20 °C until further experimentation.

Primer designing and genotyping of rs662799 polymorphism ( − 1131A > G):

The tetra-primer Amplification Refractory Mutation System-Polymerase Chain Reaction (ARMS-PCR) primers were designed using online software "OligoCalc." The primers were arranged in the following order:

OF (Outer Forward); 5′ GCTTCACTACAGGTTCCGCAG3′.

OR (Outer Reverse); 5′GCCGTGGTTTTATGTGGCAGC3′.

IF (Inner Forward); 5′ CAGGAACTGGAGCGAAAGTG3′.

IR (Inner Reverse); 5′GCTTTTCCTCATGGGGCAAATCTT3′.

Primer pairs of OR and OF produce an amplicon of 512 base pairs, while IF-OR and OF-IR produce 355 and 194 base pair amplicons, respectively.

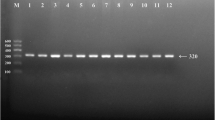

Genotyping was carried out using BIO-RAD T100 Thermal Cycler. Reaction mixture of 10 µl was prepared, having 1 µl of genomic DNA, 5 µl of master mix, 0.25 µl of each primer and final volume was made 10 µl by adding nuclease-free water (NFW), in a 200-µl PCR tube. The standardized PCR conditions for APOA5 − 1131A > G included 1 cycle of initial denaturation at 95 °C for 5 min followed by 34 cycles of denaturation at 95 °C for 35 s, annealing at 58.4 °C for 40 s, extension at 72 °C for 35 s and final extension at 72 °C for 5 min. The amplified products were electrophoresed using 2% agarose gel (Fig. 1). Three different genotypes were determined among the participants for APOA5 gene rs662799 polymorphism, i.e., AA (homozygous for allele A), AG (heterozygous for allele A and G) and GG (homozygous for allele G).

Representative photograph (gel image) of Tetra primer-ARMS PCR for the detection of rs662799 polymorphism of APOA5 gene. Presence of 355-bp band confirms the presence of allele G, while 194-bp band denotes the presence of allele A, Lane 2 and 3 showing negative and positive controls, Lane 4 showing individual with GG homozygous (512- and 355-bp band), Lane 5 showing AG heterozygous individual (512-, 355- and 194-bp band) and Lane 6 showing AA homozygous individual (512- and 194-bp band)

Statistical analysis

SigmaPlot 11.0 and Microsoft Excel 2019 were used to complete the statistical analyses. Allelic and genotypic frequency was computed by counting the number of alleles; Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium (HWE) was assessed using Chi-square test for determining the differences in genotype and allele frequencies between groups. To determine the population's divergence from HWE, the group was manually tested for the chi-square HWE. Quantitative data were presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD), and differences were tested using Student’s t-test and One-way ANOVA. Additionally, Mann–Whitney Rank Sum test, all pairwise Dunn’s test, Bonferroni t-test and Kruskal–Wallis one-way analysis of variance on ranks were applied wherever appropriate. Qualitative data were presented as frequency and percentage, and the Chi-square test was used to compare the groups. Co-dominant, recessive, dominant, over-dominant and additive models of inheritance were used to estimate odds ratios (ORs), with 95% confidence intervals (CI) across the groups for individuals carrying the mutant alleles [35]. Statistical significance was defined as standard 5% level (p < 0.05).

All the participants were divided into two groups based on the features that were noted for further analyses. The normal range of BMI was considered 18.5–22.9 kg/m2 [36, 37], so individuals were categorized into “Increased BMI (IBMI)” and “Normal BMI (NBMI)” having BMI > 22.9 and BMI ≤ 22.9, respectively. Participants having SBP (120 mmHg) and DBP (80 mmHg) normal or below (deemed normal) and above the normal readings were grouped into “Normal SBP or normal DBP (NSBP or NDBP)” and “Increased SBP or increased DBP (ISBP or IDBP),” respectively. Therefore, to find out the association of polymorphism rs662799 with the traits in question, we merged two categories to obtain better results.

Results

Characteristics of the studied population:

Table 1 displays the demographic details, anthropometric measurements and physio-metric parameters of the population studied. The current study involved 246 healthy people from North Indian areas in total, comprising approximately 56% of males and 44% of females (Table 1). The participants had a mean age of 30.37 years (standard deviation: 12.72), with statistically no significant difference in mean ages between males and females. The distribution of genotypes (AA, AG, and GG) in the population under study did not significantly differ by gender (p = 0.839). Among morphometric parameters, significantly higher (p < 0.001) values of height (cm) in males were observed than females, but non-significant differences between two genders were found in case of weight (Kg); however, BMI (Kg/m2) values were significantly higher in case of females than males (p = 0.003). The physio-metric traits recorded during the survey likewise revealed significant differences among SBP, DBP and MAP with p = 0.013, 0.036 and 0.007, respectively, but PR and PP showed non-significant differences among gender (Table 1).

Genotypic and allelic frequency of rs662799 polymorphism in APOA5 gene

Genotyping results of the individuals by Tetra-primer ARMS-PCR revealed that 63.82% of the population surveyed had AA genotype, 26.83% with AG genotype and only 9.35% with GG genotype (Additional file 1: Table S1). The genotypic and allelic frequencies were calculated by gene counting and shown in Additional file 1: Table S1. The allelic frequency for allele A i.e., f(A) was found 0.77 (major allele) and (f(G)) was 0.23 (minor allele) for allele G. Chi-squared HWE analysis for the APOA5 gene revealed significant difference (p < 0.001), suggesting that the studied population deviate from HWE Hardy–Weinberg Equilibrium meaning the population was not in equilibrium for rs662799 polymorphism of APOA5 gene (Additional file 1: Table S2).

APOA5 gene polymorphism rs662799 ( − 1131A > G) and body mass index

After applying Kruskal–Wallis one way ANOVA on height (Cm) of different genotype categories, it revealed no significant association among the groups (p = 0.817) (Fig. 2a), but Dunn’s method showed significant difference (p < 0.001) observed for weight among different genotype categories (Fig. 2b). One-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni t-test on BMI values revealed a statistically significant difference among different groups (p < 0.001) (Fig. 2c). Further analysis of two BMI categories (IBMI and NBMI) with respect to genotypes showed susceptible significant association of rs662799 polymorphism with IBMI in recessive (OR = 17.711, p < 0.001, CI (95%) = 4.05–77.46) and dominant (OR = 3.060, p < 0.001, CI (95%) = 1.78–5.25) models of inheritance, while other models revealed protective association (Table 2). IBMI category showed higher frequency (35.57%) of minor allele G as compared to NBMI (13.38%) with p value < 0.001 (Table 2). Other inheritance models might be disregarded since they did not generate satisfactory results.

Results of ANOVA among different genotypes for anthropometric traits a no significant difference (p = 0.817) were observed in case of height among the genotypes AA, AG and GG b and c showing statistically significant differences among AA-GG and AG-GG, for weight (p < 0.001) and body mass index (BMI) (p < 0.001) values of the participants (*p < 0.05)

APOA5 gene polymorphism rs662799 (-1131A > G) and Blood Pressure:

One-way ANOVA followed by all pairwise Dunn’s test revealed statistically significant differences in SBP (p = 0.004), DBP (p = 0.03) and MAP (p = 0.006) among different genotypes (AA, AG and GG) (Fig. 3a, b, e). Kruskal–Wallis one-way analysis of variance on ranks showed that PR (p = 0.431) and PP (p = 0.051) values had non-significant differences among the groups (Fig. 3c and d). Further statistical analysis conducted to test the association of increased SBP and DBP with polymorphism rs662799 in individuals with different genotypes. Among the genetic models tested for significance, recessive model of inheritance in SBP (OR = 3.792, p = 0.023, CI (95%) = 1.25–11.509) and DBP (OR = 3.83, p = 0.012, CI (95%) = 1.375–10.68) showed significant association of G allele with increase in their values (Tables 3 and 4). The ISBP (25.17%) and IDBP (29.36%) showed higher frequency of minor allele (G) as compared with NSBP and NDBP (Tables 3 and 4). Among three genotypes, although MAP showed significant difference with p = 0.006 (Fig. 3e) among genotypes, further association analysis of rs662799 with change in MAP values, i.e., neither with IMAP nor NMAP, revealed significant result under any of the inheritance models. However, the allelic frequency of minor allele was found higher in case of IMAP (25.87%) as compared to NMAP (18.45%) (Additional file 1: Table S3).

Box plots deciphering the results of ANOVA among genotypes (AA, AG and GG) for physio-metric traits, a, b and e denotes the statistically significant difference between AA and GG genotype, for systolic blood pressure (SBP) (p = 0.004), diastolic blood pressure (DBP) (p = 0.03) and mean arterial pressure (MAP) (p = 0.006), respectively, while c and d representing non-significant results among genotypes for pulse rate (PR) (p = 0.431) and pulse pressure (PP) (p = 0.051), respectively, for the study participants (*p < 0.05)

Discussion

The APOA5 rs662799 polymorphism has been widely implicated to affect the TG level and cardiovascular risks, resulting into the high BMI. The increased BMI is an indicator, frequently used to characterize obesity and to estimate adiposity; in that way, it is allied with a succession of health issues which are always grouped collectively as metabolic syndrome, including type 2 diabetes, dyslipidemia and fatty liver disease, although genetic evidence of effect of rs662799 on BMI and hypertension has been inconsistent. In the present study, we observed that there was an association of APOA5 rs662799 ( − 1131A > G) with BMI, SBP and DBP. Our genotypic data showed that the allelic frequency of minor allele (G) was 23% and major allele (A) was 77% (Additional file 1: Table S1); however, different frequencies of minor allele ranging 29.1% in Japanese, 26.7% in Chinese, and 1.7% in European population had been published [9], similarly for south Asian and global population (dbSNP, 1000Genome).

Table 1 depicts significant differences in height and BMI among males and females in our study, similar results from previous study have shown that height in males tends to be higher as compared to females, while BMI was found to be higher in females than males [38], although there is mixed research suggesting gender-based differences might be due to the influence of environment and other genes or may be due to sex hormones [39]. Moreover, difference in blood pressure is due to protective nature of some biological and behavioral factors against hypertension in females. These factors include sex hormones, chromosomal differences and other biological sex differences [40]. Our findings related to physio-metric traits also showed significantly higher blood pressure (SBP, DBP, MAP) in male participants compared to females (Table 1) as suggested by the findings from North India and other populations worldwide [38, 41,42,43].

Numerous studies have suggested the association rs662799 polymorphism of APOA5 gene in CHD, cardiovascular disease risk, metabolic syndrome, dyslipidemia, severity of CHD, cardiovascular traits, serum adipokine levels and TG [4, 9, 16, 29, 44,45,46]. Normally, the APOA5 gene is known to regulate the TG level, which results in maintaining BMI, but variation (rs662799, A-1131G) in promoter region of APOA5 is responsible for reduced expression, which fails the gene to regulate the TG level, causing increased TG and, consequently, higher BMI or obesity [33, 46, 47]. In our study, we found a significant (p < 0.001) increase in BMI (17.71-folds) among the individuals with GG genotype as compared to AG and AA genotype, under recessive model of inheritance; dominant model also showed significant odds ratio of 3.06 with CI (95%) 1.78–5.25 at p < 0.001(Table 2). In contrast with the studies [20, 48], our study suggested that the higher frequency of minor allele (35.57%) among IBMI individuals has the involvement of the allele in progression of obesity or significant increase in BMI, as reported previously [8, 49, 50].

Evidence suggests that SNP rs662799 of APOA5 gene is meticulously related with alterations of BP, serum lipid parameters, increased risk of myocardial infarction and cardiovascular risk as well as hypertension [30, 33, 49]. From our investigation, a significant association of the SNP rs662799 (A-1131G) was found with increased SBP (3.79-fold, p = 0.023) and it also increased DBP (3.83-fold, p = 0.012) among G allele carriers as compared to A allele, under recessive model of inheritance; similar results also reported by previous research [30]. The frequency of allele G was found higher in individuals having ISBP (25.17%) and IDBP (29.36%), compared to the individuals with NSBP and NDBP; this could be explained by the fact that G allele carriers of rs662799 of APOA5 gene cause alterations in cardiovascular events and consequently lead to hypertension [16]. Significant difference among the genotypes was also observed in case of MAP values (Fig. 3e), but association analysis from our data for rs662799 SNP of APOA5 gene with IMAP and NMAP individuals did not show significant results under any of the inheritance models, although previous report [30] suggested a strong positive association of − 1131 A > G polymorphism with arterial hypertension (AHT). However, further research is needed to endorse our findings regarding the association of APOA5 gene rs662799 polymorphism and quantitative traits.

Conclusions

To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first to examine the association of polymorphism rs662799 of APOA5 gene with morphometric and physio-metric traits together, among North Indian population. Our data show markedly higher BMI, systolic and diastolic blood pressure in subjects with the − 1131G allele. Hence, we suggest that the presence of minor allele G could be an early genetic marker for the identification of increased risk of obesity and cardiovascular complications. The findings of our study offer the chance to clarify the associations between the rs662799 polymorphism, BMI and BP. Clinical guideline will be eventually used for this knowledge to enhance the development of dietary therapies for people with obesity and heart disease. Exercise and nutritional treatments are two ways of lifestyle changes that should be part of weight management for those who are overweight or obese. For larger sample sizes in independent replication, investigations are necessary to provide further insight in the function of the gene under investigation in this research.

Availability of data and materials

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Abbreviations

- APOA5:

-

Apolipoprotein A5

- Kb:

-

Kilobases

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- BP:

-

Blood pressure

- ARMS-PCR:

-

Amplification refractory mutation system-polymerase chain reaction

- SBP:

-

Systolic blood pressure

- DBP:

-

Diastolic blood pressure

- µl:

-

Microliters

- sec:

-

Seconds

- min:

-

Minutes

- OR:

-

Odds ratio

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- Chr:

-

Chromosome

- TG:

-

Triglyceride

- VLDL:

-

Very low-density lipoprotein

- HDL:

-

High-density lipoprotein

- SNP:

-

Single-nucleotide polymorphism

- T2DM:

-

Type 2 diabetes mellitus

- CHD:

-

Coronary heart disease

- CAD:

-

Coronary artery disease

- PR:

-

Pulse rate

- PP:

-

Pulse pressure

- MAP:

-

Mean arterial pressure

- HWE:

-

Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

- ANOVA:

-

Analysis of variance

- IBMI:

-

Increased body mass index

- NBMI:

-

Normal body mass index

- ISBP:

-

Increased systolic blood pressure

- NSBP:

-

Normal systolic blood pressure

- IDBP:

-

Increased diastolic blood pressure

- NDBP:

-

Normal diastolic blood pressure

References

Forte TM, Ryan RO (2015) Apolipoprotein A5: extracellular and intracellular roles in triglyceride metabolism. Curr Drug Targets 16(12):1274–1280

Gombojav B, Lee SJ, Kho M, Song YM, Lee K, Sung J (2016) Multiple susceptibility loci at chromosome 11q23.3 are associated with plasma triglyceride in East Asians. J Lipid Res 57(2):318–324

Jiang CQ, Liu B, Cheung BM, Lam TH, Lin JM, Li Jin Y et al (2010) A single nucleotide polymorphism in APOA5 determines triglyceride levels in Hong Kong and Guangzhou Chinese. Eur J Hum Genet 18(11):1255–1260

Wang Y, Lu Z, Zhang J, Yang Y, Shen J, Zhang X et al (2016) The APOA5 rs662799 polymorphism is associated with dyslipidemia and the severity of coronary heart disease in Chinese women. Lipids Health Dis 15(1):170

Schaap FG, Rensen PCN, Voshol PJ, Vrins C, van der Vliet HN, Chamuleau RAFM et al (2004) ApoAV reduces plasma triglycerides by inhibiting very low density lipoprotein-triglyceride (VLDL-TG) production and stimulating lipoprotein lipase-mediated VLDL-TG hydrolysis. J Biol Chem 279(27):27941–27947

de Luis RD, Primo D, Izaola O, Aller R (2022) Association of the APOA-5 genetic variant rs662799 with metabolic changes after an intervention for 9 months with a low-calorie diet with a mediterranean profile. Nutrients 14(12):2427

Lin E, Kuo PH, Liu YL, Yang AC, Tsai SJ (2017) Detection of susceptibility loci on APOA5 and COLEC12 associated with metabolic syndrome using a genome-wide association study in a Taiwanese population. Oncotarget 8(55):93349–93359

Xu C, Bai R, Zhang D, Li Z, Zhu H, Lai M et al (2013) Effects of APOA5 −1131T>C (rs662799) on fasting plasma lipids and risk of metabolic syndrome: evidence from a case-control study in China and a meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 8(2):e56216

Ye H, Zhou A, Hong Q, Tang L, Xu X, Xin Y et al (2015) Positive Association between APOA5 rs662799 polymorphism and coronary heart disease: a case-control study and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 10(8):e0135683

You Y, Wu YH, Zhang Y, Zhang L, Song Y, Bai W et al (2018) Effects of polymorphisms in APOA5 on the plasma levels of triglycerides and risk of coronary heart disease in Jilin, Northeast China: a case–control study. BMJ Open 8(6):e020016

Priore Oliva C, Pisciotta L, Li Volti G, Sambataro MP, Cantafora A, Bellocchio A et al (2005) Inherited apolipoprotein A-V deficiency in severe hypertriglyceridemia. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 25(2):411–417

Marçais C, Verges B, Charrière S, Pruneta V, Merlin M, Billon S et al (2005) Apoa5 Q139X truncation predisposes to late-onset hyperchylomicronemia due to lipoprotein lipase impairment. J Clin Invest 115(10):2862–2869

Halalkhor S, Jalali F, Tilaki KH, Shojaei S (2014) Association of two common polymorphisms of apolipoprotein A5 gene with metabolic syndrome indicators in a North Iranian population, a cross-sectional study. J Diabet Metab Disord 13:48

Takeuchi F, Isono M, Katsuya T, Yokota M, Yamamoto K, Nabika T et al (2012) Association of genetic variants influencing lipid levels with coronary artery disease in Japanese individuals. PLoS ONE 7(9):e46385

Pennacchio LA, Olivier M, Hubacek JA, Krauss RM, Rubin EM, Cohen JC (2002) Two independent apolipoprotein A5 haplotypes influence human plasma triglyceride levels. Hum Mol Genet 11(24):3031–3038

de Luis DA, Izaola O, Primo D, Aller R (2021) APOA5 variant rs662799, role in cardiovascular traits and serum Adipokine levels in caucasian obese subjects. Ann Nutr Metab 77(5):299–306

Joy T, Hegele RA (2008) Genetics of metabolic syndrome: is there a role for phenomics? Curr Atheroscler Rep 10(3):201–208

Lim HH, Choi M, Kim JY, Lee JH, Kim OY (2014) Increased risk of obesity related to total energy intake with the APOA5-1131T > C polymorphism in Korean premenopausal women. Nutr Res N Y N 34(10):827–836

Cho AR, Hong KW, Kwon YJ, Choi JE, Lee HS, Kim HM et al (2022) Effects of single nucleotide polymorphisms and mediterranean diet in overweight or obese postmenopausal women with breast cancer receiving adjuvant hormone therapy: a pilot randomized controlled trial. Front Nutr. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnut.2022.882717

Su X, Kong Y, Peng DQ (2018) New insights into apolipoprotein A5 in controlling lipoprotein metabolism in obesity and the metabolic syndrome patients. Lipids Health Dis 17(1):174

Huang XS, Zhao SP, Hu M, Bai L, Zhang Q, Zhao W (2010) Decreased apolipoprotein A5 is implicated in insulin resistance-related hypertriglyceridemia in obesity. Atherosclerosis 210(2):563–568

Zhao SP, Hu S, Li J, Hu M, Liu Q, Wu LJ et al (2007) Association of human serum apolipoprotein A5 with lipid profiles affected by gender. Clin Chim Acta Int J Clin Chem 376(1–2):68–71

Elosua R, Ordovas JM, Cupples LA, Lai CQ, Demissie S, Fox CS et al (2006) Variants at the APOA5 locus, association with carotid atherosclerosis, and modification by obesity: the Framingham Study. J Lipid Res 47(5):990–996

Havasi V, Szolnoki Z, Talián G, Bene J, Komlósi K, Maász A et al (2006) Apolipoprotein A5 gene promoter region T-1131C polymorphism associates with elevated circulating triglyceride levels and confers susceptibility for development of ischemic stroke. J Mol Neurosci 29(2):177–183

Bi N, Yan SK, Li GP, Yin ZN, Chen BS (2004) A single nucleotide polymorphism—1131T>C in the apolipoprotein A5 gene is associated with an increased risk of coronary artery disease and alters triglyceride metabolism in Chinese. Mol Genet Metab 83(3):280–286

Liu H, Zhang S, Lin J, Li H, Huang A, Xiao C et al (2005) Association between DNA variant sites in the apolipoprotein A5 gene and coronary heart disease in Chinese. Metabolism 54(5):568–572

Yin YW, Sun QQ, Wang PJ, Qiao L, Hu AM, Liu HL et al (2014) Genetic polymorphism of apolipoprotein A5 gene and susceptibility to Type 2 diabetes mellitus: a meta-analysis of 15,137 subjects. PLoS ONE 9(2):e89167

Yamada Y, Ando F, Shimokata H (2008) Association of the genetic variants of APOA5 and PRKCH with hypertension in community-dwelling Japanese individuals. Mol Med Rep 1(3):407–414

Dallongeville J, Cottel D, Montaye M, Codron V, Amouyel P, Helbecque N (2006) Impact of APOA5/A4/C3 genetic polymorphisms on lipid variables and cardiovascular disease risk in French men. Int J Cardiol 106(2):152–156

Ouatou S, Ajjemami M, Charoute H, Sefri H, Ghalim N, Rhaissi H et al (2014) Association of APOA5 rs662799 and rs3135506 polymorphisms with arterial hypertension in Moroccan patients. Lipids Health Dis 1(13):60

Talmud PJ, Martin S, Taskinen MR, Frick MH, Nieminen MS, Kesäniemi YA et al (2004) APOA5 gene variants, lipoprotein particle distribution, and progression of coronary heart disease: results from the LOCAT study. J Lipid Res 45(4):750–756

Kusterer K, Pohl T, Fortmeyer HP, März W, Scharnagl H, Oldenburg A et al (1999) Chronic selective hypertriglyceridemia impairs endothelium-dependent vasodilatation in rats. Cardiovasc Res 42(3):783–793

Chauhan W, Fatma R, Wahab A, Afzal M (2022) Cataloging the potential SNPs (single nucleotide polymorphisms) associated with quantitative traits, viz. BMI (body mass index), IQ (intelligence quotient) and BP (blood pressure): an updated review. Egypt J Med Hum Genet. 23(1):57

Thomas JC, Khoury R, Neeley CK, Akroush AM, Davies EC (1997) A fast CTAB method of human DNA isolation for polymerase chain reaction applications. Biochem Educ 25(4):233–235

Lettre G, Lange C, Hirschhorn JN (2007) Genetic model testing and statistical power in population-based association studies of quantitative traits. Genet Epidemiol 31(4):358–362

Aziz N, Kallur SD, Nirmalan PK (2014) Implications of the revised consensus body mass indices for asian indians on clinical obstetric practice. J Clin Diagn Res JCDR 8(5):OC01-03

Pan WH, Yeh WT (2008) How to define obesity? Evidence-based multiple action points for public awareness, screening, and treatment: an extension of Asian-Pacific recommendations. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr 17(3):370–374

Fatma R, Chauhan W, Shahi M, Afzal M (2023) Association of BDNF gene missense polymorphism rs6265 (Val66Met) with three quantitative traits, namely, intelligence quotient, body mass index, and blood pressure: a genetic association analysis from North India. Front Neurol 20:13

Singh SK, Dubey PP. A Comparative analysis of BMI among males and females aged between 15–75 years. 2018:5(1):3.

Everett B, Zajacova A (2015) Gender differences in hypertension and hypertension awareness among young adults. Biodemography Soc Biol 61(1):1–17

Alhawari HH, Al-Shelleh S, Alhawari HH, Al-Saudi A, Aljbour Al-Majali D, Al-Faris L et al (2018) Blood pressure and its association with gender, body mass index, smoking, and family history among university students. Int J Hypertens 29(2018):e4186496

Cossio-Bolaños M, Cossio-Bolaños W, Menacho A, Go A, Silva Y, Pablos C et al (2014) Nutritional status and blood pressure in adolescent students. Arch Argent Pediatr 1(112):302–307

Nwachukwu DC, Nwagha U, Obikili EN, Ejezie FE, Okwuosa CN, Nweke ML et al (2010) Assessment of body mass index and blood pressure among University Students in, Enugu, South East, Nigeria. Niger J Med. https://doi.org/10.4314/njm.v19i2.56503

Chen H, Ding S, Zhou M, Wu X, Liu X, Wu Y et al (2018) Association of rs662799 in APOA5 with CAD in Chinese Han population. BMC Cardiovasc Disord 18(1):2

Hechmi M, Dallali H, Gharbi M, Jmel H, Fassatoui M, Ben Halima Y et al (2020) Association of rs662799 variant and APOA5 gene haplotypes with metabolic syndrome and its components: a meta-analysis in North Africa. Biosci Rep 40(8):BSR20200706

Jasim AA, Al-Bustan SA, Al-Kandari W, Al-Serri A, AlAskar H (2018) Sequence analysis of APOA5 among the Kuwaiti population identifies association of rs2072560, rs2266788, and rs662799 With TG and VLDL Levels. Front Genet 9(9):112

Wang X, Liu J, Cheng Z, Zhong Y, Chen X, Song W (2021) Triglyceride glucose-body mass index and the risk of diabetes: a general population-based cohort study. Lipids Health Dis 20(1):99

Corella D, Lai CQ, Demissie S, Cupples LA, Manning AK, Tucker KL et al (2007) APOA5 gene variation modulates the effects of dietary fat intake on body mass index and obesity risk in the Framingham Heart Study. J Mol Med Berl Ger 85(2):119–128

Hubacek JA, Skodová Z, Adámková V, Lánská V, Poledne R (2004) The influence of APOAV polymorphisms (T-1131>C and S19>W) on plasma triglyceride levels and risk of myocardial infarction. Clin Genet 65(2):126–130

Zhu WF, Wang CL, Liang L, Shen Z, Fu JF, Liu PN et al (2014) Triglyceride-raising APOA5 genetic variants are associated with obesity and non-HDL-C in Chinese children and adolescents. Lipids Health Dis 5(13):93

Acknowledgements

Maulana Azad National Fellowship (MANF-2018-19-UTT-100618) under University Grants Commission (UGC) to the first author is highly acknowledged. The authors are also grateful to all of the research participants involved in the study for their cooperation.

Funding

This research was self-funded and did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

RF took part in conceptualization, study design, data curation, experimental work, data analysis, investigation, methodology, resources, original draft, writing—review and editing. WC involved in data analysis, investigation, conceptualization, writing—review and editing. SR and KR took part in resources, experimental work, writing manuscript. MA involved in supervision, study design, validation, visualization, conceptualization, formal analysis. All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The protocols of the present study were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Ethical Committee, Jawaharlal Nehru Medical College (JNMC), Aligarh Muslim University, India. Written informed consent to participate in this study was provided by the participants on their own or by their legal guardian/next of kin.

Consent for publication

We obtained written informed consent with signature from all the included participants or their legal guardians for publication.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1.

Tables of genotype and allele frequency details as per Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium and significance level with odds ratio analysis under different models.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Fatma, R., Chauhan, W., Riyaz, S. et al. Genetic association analysis of rs662799 ( − 1131A > G) polymorphism of APOA5 gene with morphometric and physio-metric traits using multiplex PCR. Egypt J Med Hum Genet 24, 19 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s43042-023-00398-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s43042-023-00398-x