Abstract

Background

ATP-binding cassette transporters A1/G1 (ABCA1/G1) is a main regulator of HDL (high-density lipoprotein) formation and reverse cholesterol transport. Impaired ABCA1/G1 genes function may seriously affect cholesterol homeostasis, leading to increased risk of cardiovascular disease. In the present study, the association of ABCA1/G1 genes methylation status with the risk of coronary artery disease (CAD), risk factors of CAD, and serum level of lipid parameters was investigated.

This study was conducted on 70 CAD patients and 40 control subjects. All CAD subjects with diabetes mellitus were excluded. The promoter methylation status of ABCA1/G1 genes was determined by the methylation-specific polymerase chain reaction (MS-PCR) method and serum lipid parameters were assessed using commercial kits.

Results

ABCA1 promoter methylation was higher in CAD group compared to the control participants (80% vs. 60%). Hypermethylation of the ABCA1 gene significantly increases the risk of CAD in the total population (OR 3.886, 95% CI (1.181–12.791), p = 0.026). ABCG1 methylation status showed no difference between CAD and control subjects. In addition, no significant association was noted between methylation status of ABCA1/G1 and serum level of lipid profile.

Conclusions

Altogether, our study shows that ABCA1 gene promoter hypermethylation may increase the risk of CAD, which may help identify people at risk of developing CAD.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Coronary artery disease (CAD), the most common form of cardiovascular disease (CVD), is one of the main causes of mortality and morbidity worldwide [1]. Atherosclerosis, the leading cause of CAD, is a chronic inflammatory disorder with lipid deposition in coronary arteries that in turn develop angina pectoris, myocardial infarction (MI), and death [2].

Genetic and environmental factors such as poor diet, a family history of CAD, aging, smoking, hypertension, diabetes, and dyslipidemia are considered as risk factors for CAD. Dyslipidemia, as a key predictor of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, is defined as an increase in plasma total cholesterol (TC), triglyceride (TG), low-density lipoprotein-cholesterol (LDL-C), and decrease in high-density lipoprotein-cholesterol (HDL-C) [3]. CAD is treated mainly through lifestyle changes, such as exercising, eating a healthy diet, and controlling body weight. In some cases, the use of drugs that lower cholesterol and blood pressure, as well as beta blockers and aspirin are also prescribed [4].

The inverse association between HDL-C and CVD risk is well established [5]. However, previous studies have failed to show the beneficial effect of increasing HDL-C on CVD outcome improvement [6]. One reason that should be considered is the complexity of HDL metabolism.

ATP-binding cassette transporters A1/G1 (ABCA1/G1) is one of the most important genes that associated with HDL metabolism [7]. ABCA1/G1 as a member of ATP-binding cassette (ABC) superfamily is responsible for HDL-C formation through cholesterol efflux from non-hepatic peripheral tissues (e.g., macrophages and vascular smooth muscle cells) to extracellular lipid acceptors [8]. ABCA1/G1 genes are crucial for cholesterol homeostasis and plasma HDL-C level regulation. Dysfunction of these genes will dramatically impair cholesterol and lipid transport, leading to a higher risk for premature CAD [9]. ABCA1 gene mutations were shown to be involved in the pathogenesis of Tangier disease (TGD, OMIM 205400) [10] and familial hypoalphalipoproteinemia (FHA, OMIM 604091) characterized by the absence of plasma HDL-C and increased susceptibility to CAD [11]. Furthermore, pieces of evidence indicate that upregulation of ABCA1/G1 genes can significantly alleviate macrophage lipid deposition and atherogenesis [10, 12].

Apolipoprotein A1 (ApoA1) is a key protein component of HDL particle and acts as the main acceptor for cholesterol efflux by ABCA1 [13]. Previous studies demonstrate increase serum level of apolipoprotein B (ApoB) and decrease level of ApoA1 are significantly associated with enhanced cardiovascular event [14, 15]. In addition, it has been shown that ApoA1and ApoB level and ApoB/ApoA1 ratio are more accurate markers of cardiovascular risk compared to LDL-C and TC [16].

The exact regulatory mechanisms of ABCA1/G1 are still unknown. It has been well established that DNA methylation plays a critical role in gene expression regulation [17]. In general, gene promoter hypomethylation can upregulate gene expression, whereas gene promoter hypermethylation can suppress gene expression [18]. Previous studies have stated that differential promoter methylation in candidate genes contributes to CAD risk variability [19, 20].

Although ABCA1 and ABCG1 play key roles in regulating HDL-C level, few works were available regarding epigenetic modification of these genes in CAD [21, 22]. The present study aimed to investigate the association between ABCA1 and ABCG1 genes methylation status and the risk of CAD. It is well demonstrated that diabetes can significantly alter the methylation status of genes [23], so in the present work, CAD patients without diabetes were selected. The methylation alteration of ABCG1 in diabetes mellitus patients was shown previously [24, 25]. Another aim of our study was to evaluate the association of the methylation status of ABCA1/G1 genes with serum levels of lipids, apolipoproteins, and patients’ clinical characteristics.

Method and materials

Study subjects

This cross-sectional study was performed on 110 patients suffering from chest pain and dyspnea. Sample size was determined according to the following formula [26]:

The participants were selected among people who underwent coronary angiography for the first time. Subjects were excluded if they had any malignancy, chronic liver and kidney diseases, inflammatory disease, thyroid disease, any history of cardiovascular disease, and operation in the last 2 months. Subjects with diabetes mellitus were also excluded. Patients were defined as a diabetic if they had taken antidiabetic medications, previously diagnosed as diabetic, had fasting blood sugar equal or greater than 126 mg/dl or positive results of an oral standard glucose tolerance test [27].

According to angiography results, participants were divided into two groups: CAD group with at least 50% stenosis in at least one major coronary artery (n = 70) and control group with no stenosis in coronary arteries (n = 40). The control group had a completely normal angiogram [28]. The study protocol was in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the local ethics committee (Ref: IR.HUMS.REC.1394. 82, Bandar Abbas, Iran, 2018). Informed consent was obtained from all subjects before being recruited for the study.

Biochemical analyses

Overnight fasting venous blood samples were obtained at admission, before administration of angiography contrast agent. The blood was collected in tubes and allowed 30 min to clot at room temperature. The serum was separated by centrifugation at 3000 rpm for 10 min and stored at − 80 °C [29]. Blood samples containing anticoagulant (K2EDTA 1 mg/ml) were used for genomic DNA extraction. All lipid indexes were measured using standard commercial kits (Pars Azmoon Company, Tehran, Iran) and BS-800 automatic biochemical analyzer (Mindray Company, UK). Total cholesterol (kit lot No: 97003) and triglyceride (kit lot No:97002) were determined using enzymatic CHOD-PAP and GPO-PAP colorimetric methods, respectively. LDL-C was assessed according to the Friedewald formula, in subjects with TG > 400 mg/dl [30]. In those subjects with TG more than 400 mg/dl, a direct method using a commercial kit (lot No:97001) was used to determine LDL-C. Serum HDL-C (kit lot No:97011) was assessed by homogeneous assay. The serum levels of ApoA1 (kit lot No: 96012) and ApoB (kit lot No:96013) were assessed using auto analyzer BS-800 (Mindray Company, UK) by the immunoturbidimetric method and standard commercial kits (Pars Azmoon Company, Tehran, Iran). The inter-assay coefficient of variation (%CV) for triglyceride, total cholesterol, HDL-C, and LDL-C was 2.8, 2.9, 1.0, and 2.3, respectively.

Genomic DNA extraction, bisulfite treatment, and methylation-specific PCR

Genomic DNA was extracted from whole blood using the salting-out method [31]. Quantity and quality of DNA were assessed by the Nanodrop spectrophotometer (NanoDrop 2000c, Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) and gel electrophoresis, respectively. For each sample, 2 μg of extracted DNA was used for bisulfite treatment [32]. In bisulfite modification, unmethylated cytosine converts to uracil while methylated cytosine will remain unchanged. After purification of modified DNA with commercial columns (Roche Company, Germany), methylation of ABCA1 and ABCG1 was assessed using methylation-specific polymerase chain reaction method (MS-PCR) and specific primers for methylated and unmethylated regions (Table 1). All PCR reagents (cat No:YT1591) were from Yekta Taghiz company (Tehran, Iran).

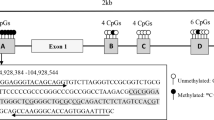

PCR reaction in 50 μl volume for methylated primers of both ABCA1/G1 was contained: 5 μl PCR buffer (10X), 3 μl MgCl2 50 mM, 1 μl dNTP (10 mM), 0.4 μl Taq polymerase (5 U/μl), 1.25 μl of each forward and reverse primers (10 μM), and 2 μl of modified DNA. PCR reaction in 50 μl volume for ABCA1/G1 unmethylated primers consisted of 5 μl PCR buffer (10X), 1.5 μl MgCl2 50 mM, 1 μl dNTP (10 mM), 0.25 μl Taq polymerase (5 U/μl), 2.5 μl of each forward and reverse primers (10 μM), and 2 μl of modified DNA. The conditions for PCR amplification were as follows: an initial denaturation step at 95 °C for 2 min followed by 35 cycles consisting of denaturation at 95 °C for 15 s, annealing at 58.5 °C (ABCA1 methylated primer), 51 °C (ABCA1 unmethylated primer), 54 °C (methylated ABCG1 primer), and 48 °C (unmethylated ABCG1 primer) for 30 s, and extension at 72 °C for 30 s. Following these cycles, the final extension was performed at 72 °C for 5 min. Commercially human methylated and non-methylated DNA set (Zymo Research Company, USA, Cat No:D5011) were used as control. Ultimately, for determining the methylation pattern, PCR products were run on 2% agarose gel (Pars Tous Biotechnology company, Mahshad, Iran, cat No: B111192) stained with GelRed (Biotinum company, Fremont USA, cat No:41001) and visualized under UV illumination (Fig. 1).

The electrophoresis gel photograph of methylation status analysis of the ABCA1/G1 gene promoter. a Lanes 1,2, and 3 represent the methylated, unmethylated, and hemimethylated status of the ABCA1 gene in three participants, respectively. b Lanes 1,2, and 3 represent the methylated, unmethylated, and hemimethylated status of the ABCG1 gene in three participants, respectively. As a standard methylated and unmethylated control, commercially methylated and unmethylated DNA control were used, respectively. M: methylated-specific primer, U: unmethylated-specific primer

Statistical analyses

Data normality was checked for all continuous variables using the Shapiro–Wilk test. Anthropometric and laboratory characteristics of participants were reported as mean±SD for continuous variables with normal distribution, as median (IQR) for continuous variables with non-normal distribution and as number/percentage for categorical variables. The comparison of anthropometric and laboratory data with normal distribution was carried out using independent t test and for not normally distributed data, the Mann–Whitney U test was used. For evaluation of categorical variables, the Chi-square test was performed for normally distributed data and Mann–Whitney U test was performed for data with non-normal distribution. Log transformation was performed for non-normal distributed variables. To determine the relation of ABCA1/G1 methylation and clinical variables, each variable was separately entered in a univariate logistic regression model; then, the variables which had a p < 0.2 were selected and entered into a multiple regression model using forward stepwise method and odds ratios (OR), 95% confidence intervals (CI), and p value was estimated. The correlation coefficient was employed by two-tailed Pearson's correlation analysis to examine the correlation of ApoA1, ApoB, and ApoB/ApoA1 with lipid profiles. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software version 16.0 (SPSS Inc. Chicago, IL, USA) and were reported two-tailed. P values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Anthropometric and laboratory parameters of the study population based on CAD and gender subgroup analysis

The anthropometric, clinical, and laboratory parameters of the study participants are shown in Table 2. The mean age of control and CAD groups were 51.63 ± 10.53 and 54.84 ± 8.18 years, respectively (p = 0.10). The mean of systolic blood pressure was markedly higher in CAD group than in control group. Subgroup analysis according to gender shows that BMI and systolic blood pressure among women were significantly higher than men (P ˂ 0.05). The methylation status of the ABCA1 gene promoter (at cg05286874) was detected in 80% of CAD and 60% of control group and the differences were statistically significant (P = 0.023). Furthermore, the ABCA1 gene promoter was hypermethylated in 85.7% of women and 66.7% of men (P = 0.037). 60% of participants in the control group and 41.4% of subjects in the CAD group were hypermethylated for ABCG1 (P > 0.05). Also, ABCG1 methylation (chr21:42296214-42296464) was detected in 44% of men and 57.1% of women but the differences were not statistically significant.

Association between ABCA1 and ABCG1 methylation and CAD risk factors

According to Table 3, 70% (56/80 × 100 = 70%) of participants with ABCA1 promoter hypermethylation suffer from CAD, whereas just 46.66% (14/30 × 100 = 46.6%) of the study subjects with unmethylated ABCA1 had CAD. This difference remains significant even after adjustment for potential confounders that can affect ABCA1 promoter methylation including age, gender, smoking, and aspirin medication. The ratio of male to female in the unmethylated group is markedly higher than in the methylated group. 62.5% (50/80 × 100 = 62.5%) of subjects with methylated status of ABCA1 were men while in the unmethylated group, 83.3% (25/30 × 100 = 83.3%) were men. There was no association between ABCA1 promoter methylation and serum level of lipids and apolipoproteins. According to Table 4, the percentage of men with ABCA1 promoter hypermethylation in the CAD group was markedly higher than in the control group (p=0.021). The same pattern of ABCA1 methylation was observed for women but the differences among women were not significant (Table 4).

The association between ABCG1 methylation pattern and CAD-related risk factors is summarized in Table 5. 54.72% (29/53 × 100 = 54.72%) of subjects in the methylated group had CAD while 71.93% (41/57 × 100 = 71.93%) of the unmethylated group suffered from CAD and the difference was partially significant (p value = 0.061). Lipid profile and apolipoproteins show no significant association with ABCG1 methylation status. The result of gender subgroup analysis is presented in Table 6.

Correlation of serum ApoA1, ApoB, and ApoB/ApoA with the study variables

Bivariate correlation analysis of ApoA1, ApoB, and ApoB/ApoA1 with anthropometric and laboratory variables in the study population is shown in Table 7. A positive significant correlation between serum ApoA1 level and age (r = 0.337, P < 0.001), systolic blood pressure (r = 0.261, P = 0.006), and HDL-C (r = 0.578, P < 0.001) was indicated. Additionally, serum ApoB had a positive significant correlation with TG (r = 0.321, P = 0.001), TC (r = 0.534, P < 0.001), and LDL-C (r = 0.372, P < 0.001). Moreover, a significant negative correlation between ApoB/ApoA1 ratio and age (r = − 0.200, P = 0.036) and HDL-C (r = − 0.278, P = 0.003) was noted. Finally, a significant positive correlation between ApoB/ApoA1 ratio and TG (r = 0.232, P = 0.015), TC (r = 0.386, P < 0.001), and LDL-C (r = 0.342, P < 0.001) were observed.

Discussion

The aim of the present investigation was to assess the methylation status of ABCA1/G1 in non-diabetic CAD patients and control participants. Also, the association of methylation pattern of these genes with CAD and CAD-related risk factors, especially serum levels of HDL-C, ApoA1, ApoB, and ApoB/ApoA1, are shown. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report in which the methylation status of ABCA1/G1 in non-diabetic CAD patients was studied.

In our study, the methylated form of the ABCA1 gene was higher in CAD group than control subjects. We have shown the association of ABCA1 gene promoter hypermethylation with non-diabetic coronary artery disease patients. In agreement with our results, Ghaznavi et al. showed an association between ABCA1 gene hypermethylation and the risk of CAD [21]. However, in their study, the control group was selected among healthy participants without angiography confirmation. Therefore, the presence of coronary artery stenosis could not be ruled out in their control subjects [21]. Moreover, Guay et al. observed that ABCA1 gene promoter methylation has a direct correlation with CAD occurrence and aging among men [22]. In line with Guay et al. study, we showed that ABCA1 methylation was associated with older age and a higher risk of CAD. As mentioned before, we found a higher percentage of ABCA1 methylation among women than men. However, in Guay et al. investigation the methylation status of ABCA1 was not compared between women and men, because their study was only conducted on men subjects [22]. In another study, the researchers have reported that ABCA1 gene promoter methylation was higher in familial hypercholesterolemia (FH) patients with CAD history rather than FH subjects without CAD history. FH is related to more susceptibility to CAD while our participants had no inherited abnormality [19].

Our results revealed that ABCG1 methylation in the control group was higher than in CAD group. However, the data were not statistically significant. In contrast to our finding, Peng et al. observed that ABCG1 gene hypermethylation increases the risk of CAD [26]. There are no consistent data about the role of ABCG1 in CAD pathogenesis. Pieces of evidence reveal the protective role of ABCG1 against CAD development [10, 12], while some researchers had documented the deleterious effect of ABCG1 in atherosclerosis and CAD development [33, 34]. On the other hand, in the aforementioned studies, a considerable percentage of the CAD subjects had also diabetes and based on available data diabetes could alter the genes methylation pattern [23, 35, 36]. Therefore, to find a real association between ABCA1/G1 and the risk of CAD it is essential to exclude CAD patients with diabetes. In the present work, we excluded all diabetic subjects in both CAD and control groups. This could markedly strengthen the validity of our results and can more accurately reveal the association of ABCA1/G1 methylation with the risk of CAD.

We did not find any association of ABCA1/G1 methylation status with lipid profile, ApoA1, ApoB, and ApoB/ApoA1 ratio. In Guay et al. study, higher ABCA1 methylation is related positively to TC, LDL-C, and TG levels in men older than 61 years but not in younger participants [22]. In the present work, the mean age of participants in all groups was lower than 54 years old. Albeit, there are inconsistent shreds of evidence about the relationship between ABCA1/G1 methylation status and serum lipid profile level. Some researchers suggested the positive correlation between ABCA1/G1 gene methylation and TG and LDL-C and others show a negative correlation between ABCA1/G1 gene methylation and HDL-C [19, 22, 37].

A growing body of evidence had indicated the ratio of ApoB/ApoA1 as a better predictor for CAD than TC/HDL-C [38]. In the present work, we fail to indicate the significant association between ApoB/ApoA1 and CAD risk or between ABCA1/G1 methylation and serum lipid profile level. This lack of association may be partly related to antihyperlipidemic medications that were used by most of our study participants. In fact, 70% of the control group and 72.9% of CAD patients received statins for modulating their serum cholesterol.

Our study had some limitation. First, we had a limited sample size. Other studies with a larger sample size are required to confirm our results. Second, our participants took some medications such as statins and aspirin which might affect the methylation status of ABCA1/G1 genes.

Future directions

Accumulating evidence demonstrate that hypermethylation and hypomethylation of DNA can lead to changes in gene expression. In the future work, it is better to study the methylation status of ABCA1/G1 genes along with mRNA and protein expression level in order to show the more precise impact of the methylation change of these genes on the risk of CAD.

Conclusion

Altogether, our study showed that ABCA1 gene promoter hypermethylation may increase the risk of CAD, which may help identify people at risk of developing CAD. However, we could not show any association between methylation status of ABCA1/G1 and serum level of APOA1, APOB, and lipid profile. Therefore, other basic and clinical studies are needed to show the effect of methylation status of these genes on the serum level of lipid parameters.

Availability of data and materials

The data are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- ABCA1/G1:

-

ATP-binding cassette transporters A1/G1

- CAD:

-

Coronary artery disease

- MS-PCR:

-

Methylation-specific polymerase chain reaction

- CVD:

-

Cardiovascular disease

- MI:

-

Myocardial infarction

- TC:

-

Total cholesterol

- TG:

-

Triglyceride

- LDL-C:

-

Low-density lipoprotein-cholesterol

- HDL-C:

-

High-density lipoprotein-cholesterol

- ApoA1:

-

Apolipoprotein A1

- ABC:

-

ATP-binding cassette

- FH:

-

Familial hypercholesterolemia

References

WHO (World Health Organ) (2017) Cardiovascular Diseases (CVDs). https://www.who.int/news-room/factsheets/detail/cardiovascular-diseases-(cvds). Accessed 20 Feb 2022

Bakshi C, Vijayvergiya R, Dhawan V (2019) Aberrant DNA methylation of M1-macrophage genes in coronary artery disease. Sci Rep 9:1429. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-38040-1

Kopin L, Lowenstein C (2017) Dyslipidemia. Ann Intern Med 167:ITC81–ITC96. https://doi.org/10.7326/AITC201712050

Jia S, Liu Y, Yuan J (2020) Evidence in guidelines for treatment of coronary artery disease. Adv Exp Med Biol 1177:37–73. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-15-2517-9_2

Casula M, Colpani O, Xie S, Catapano AL, Baragetti A (2021) HDL in atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease: in search of a role. Cells 10:1869. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells10081869

Tuteja S, Rader DJ (2014) High-density lipoproteins in the prevention of cardiovascular disease: changing the paradigm. Clin Pharmacol Ther 96:48–56. https://doi.org/10.1038/clpt.2014.79

Yu XH, Tang CK (2022) ABCA1, ABCG1, and cholesterol homeostasis. Adv Exp Med Biol 1377:95–107. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-19-1592-5_7

Ren K, Li H, Zhou HF, Liang Y, Tong M, Chen L et al (2019) Mangiferin promotes macrophage cholesterol efflux and protects against atherosclerosis by augmenting the expression of ABCA1 and ABCG1. Aging (Albany NY) 11:10992–11009. https://doi.org/10.18632/aging.102498

Schumacher T, Benndorf RA (2017) ABC transport proteins in cardiovascular disease-a brief summary. Molecules 22:589. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules22040589

Kämmerer I, Ringseis R, Biemann R, Wen G, Eder K (2011) 13-hydroxy linoleic acid increases expression of the cholesterol transporters ABCA1, ABCG1 and SR-BI and stimulates apoA-I-dependent cholesterol efflux in RAW264.7 macrophages. Lipids Health Dis 10:222. https://doi.org/10.1186/1476-511X-10-222

Babashamsi MM, Koukhaloo SZ, Halalkhor S, Salimi A, Babashamsi M (2019) ABCA1 and metabolic syndrome; a review of the ABCA1 role in HDL-VLDL production, insulin-glucose homeostasis, inflammation and obesity. Diabetes Metab Syndr 13:1529–1534. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dsx.2019.03.004

Uehara Y, Saku K (2014) High-density lipoprotein and atherosclerosis: roles of lipid transporters. World J Cardiol 6:1049–1059. https://doi.org/10.4330/wjc.v6.i10.1049

Wang N, Tall AR (2003) Regulation and mechanisms of ATP-binding cassette transporter A1-mediated cellular cholesterol efflux. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 23:1178–1184. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.ATV.0000075912.83860.26

Walldius G, Jungner I (2004) Apolipoprotein B and apolipoprotein A-I: risk indicators of coronary heart disease and targets for lipid-modifying therapy. J Intern Med 255:188–205. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2796.2003.01276.x

Walldius G, Jungner I (2005) Rationale for using apolipoprotein B and apolipoprotein A-I as indicators of cardiac risk and as targets for lipid-lowering therapy. Eur Heart J 26:210–212. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehi077

Behbodikhah J, Ahmed S, Elyasi A, Kasselman LJ, De Leon J, Glass AD et al (2021) Apolipoprotein B and cardiovascular disease: biomarker and potential therapeutic target. Metabolites 11:690. https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo11100690

Prasher D, Greenway SC, Singh RB (2020) The impact of epigenetics on cardiovascular disease. Biochem Cell Biol 98:12–22. https://doi.org/10.1139/bcb-2019-0045

Duan L, Hu J, Xiong X, Liu Y, Wang J (2018) The role of DNA methylation in coronary artery disease. Gene 646:91–97. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gene.2017.12.033

Guay SP, Brisson D, Munger J, Lamarche B, Gaudet D, Bouchard L (2012) ABCA1 gene promoter DNA methylation is associated with HDL particle profile and coronary artery disease in familial hypercholesterolemia. Epigenetics 7:464–472. https://doi.org/10.4161/epi.19633

Sharma P, Garg G, Kumar A, Mohammad F, Kumar SR, Tanwar VS et al (2014) Genome wide DNA methylation profiling for epigenetic alteration in coronary artery disease patients. Gene 541:31–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gene.2014.02.034

Ghaznavi H, Mahmoodi K, Soltanpour MS (2018) A preliminary study of the association between the ABCA1 gene promoter DNA methylation and coronary artery disease risk. Mol Biol Res Commun 7:59–65. https://doi.org/10.22099/mbrc.2018.28910.1312

Guay SP, Légaré C, Houde AA, Mathieu P, Bossé Y, Bouchard L (2014) Acetylsalicylic acid, aging and coronary artery disease are associated with ABCA1 DNA methylation in men. Clin Epigenetics 6:14. https://doi.org/10.1186/1868-7083-6-14

Raciti GA, Desiderio A, Longo M, Leone A, Zatterale F, Prevenzano I et al (2021) DNA methylation and type 2 diabetes: novel biomarkers for risk assessment? Int J Mol Sci 22:11652. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms222111652

Walaszczyk E, Luijten M, Spijkerman AMW, Bonder MJ, Lutgers HL, Snieder H et al (2018) DNA methylation markers associated with type 2 diabetes, fasting glucose and HbA1c levels: a systematic review and replication in a case-control sample of the Lifelines study. Diabetologia 61:354–368. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-017-4497-7

Cardona A, Day FR, Perry JRB, Loh M, Chu AY, Lehne B et al (2019) Epigenome-wide association study of incident type 2 diabetes in a British population: EPIC-Norfolk study. Diabetes 68:2315–2326. https://doi.org/10.2337/db18-0290

Peng P, Wang L, Yang X, Huang X, Ba Y, Chen X et al (2014) A preliminary study of the relationship between promoter methylation of the ABCG1, GALNT2 and HMGCR genes and coronary heart disease. PLoS ONE 9:e102265. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0102265

Kerner W, Brückel J (2014) German Diabetes Association. Definition, classification and diagnosis of diabetes mellitus. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes 122:384–386. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0034-1366278

Esmaeili F, Mansouri E, Emami MA, Montazerghaem H, Hosseini Teshnizi S, Kheirandish M et al (2022) Association of serum level and DNA methylation status of brain-derived neurotrophic factor with the severity of coronary artery disease. Indian J Clin Biochem 37:159–168. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12291-021-00974-1

Sobhani AR, Farshidi H, Azarkish F, Eslami M, Eftekhar E, Keshavarz M (2020) Magnesium sulfate improves some risk factors for atherosclerosis in patients suffering from one or two coronary artery diseases: a double-blind clinical trial study. Clin Pharmacol 12:159–169. https://doi.org/10.2147/CPAA.S261264

Krishnaveni P, Gowda VM (2015) Assessing the validity of Friedewald’s formula and anandraja’s formula for serum LDL-cholesterol calculation. J Clin Diagn Res 9:BC01–BC04. https://doi.org/10.7860/JCDR/2015/16850.6870

Miller SA, Dykes DD, Polesky HF (1988) A simple salting out procedure for extracting DNA from human nucleated cells. Nucleic Acids Res 16:1215. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/16.3.1215

Hayatsu H, Shiraishi M, Negishi K (2008) Bisulfite modification for analysis of DNA methylation. Curr Protoc Nucleic Acid Chem. https://doi.org/10.1002/0471142700.nc0610s33

Le Goff W, Dallinga-Thie GM (2011) ABCG1: not as good as expected? Atherosclerosis 219:393–394. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2011.07.015

Xu Y, Wang W, Zhang L, Qi LP, Li LY, Chen LF et al (2011) A polymorphism in the ABCG1 promoter is functionally associated with coronary artery disease in a Chinese Han population. Atherosclerosis 219:648–654. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2011.05.043

Kirchner H, Sinha I, Gao H, Ruby MA, Schönke M, Lindvall JM et al (2016) Altered DNA methylation of glycolytic and lipogenic genes in liver from obese and type 2 diabetic patients. Mol Metab 5:171–183. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molmet.2015.12.004

Martín-Núñez GM, Rubio-Martín E, Cabrera-Mulero R, Rojo-Martínez G, Olveira G, Valdés S et al (2014) Type 2 diabetes mellitus in relation to global LINE-1 DNA methylation in peripheral blood: a cohort study. Epigenetics 9:1322–1328. https://doi.org/10.4161/15592294.2014.969617

Pfeiffer L, Wahl S, Pilling LC, Reischl E, Sandling JK, Kunze S et al (2006) DNA methylation of lipid-related genes affects blood lipid levels. Circ Cardiovasc Genet 8:334–342. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.114.000804

Tian M, Li R, Shan Z, Wang DW, Jiang J, Cui G (2019) Comparison of apolipoprotein B/A1 ratio, Framingham risk score and TC/HDL-c for predicting clinical outcomes in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention. Lipids Health Dis 18:202. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12944-019-1144-y

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This research has been funded by the Hormozgan University of medical sciences.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

EM was involved in data collection, and performed the experiment. FE helped in data collection, performed the experiment, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript. MM analyzed the data; MA E studied conception or design. SK performed the experiment, and wrote the manuscript. MK studied conception or design. HZ studied conception or design. HT studied conception or design. EE contributed to supervision, studied conception or design, helped in critical revision or editing of the article. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This research has been approved by the University Ethics Committee (IR.HUMS.REC.1394.82). All participants were given informed consent and were properly informed of the procedure.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mansouri, E., Esmaeili, F., Montaseri, M. et al. Association of methylation status of ABCA1/G1 genes with the risk of coronary artery disease. Egypt J Med Hum Genet 23, 167 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s43042-022-00381-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s43042-022-00381-y