Abstract

Background

The use of long stems for severe femoral bone defects is suggested by many scholars, but it is associated with further bone loss, intraoperative fracture, increased surgical trauma, and complications. With better bone retention, simple and quick surgical procedures, and minimal complications, the short cementless stems with a tapered rectangular shape may be an alternative for femoral revision. This study aimed to evaluate the results of this type of stem in treating selected Paprosky II–IV bone defects.

Methods

This retrospective study included 73 patients (76 hips involved) who underwent conservative femoral revision using the short cementless stems with a tapered rectangular shape between January 2012 and December 2020. The preoperative femoral bone defects were identified as follows: 54 cases of type II, 11 cases of type IIIA, 7 cases of type IIIB, and 4 cases of type IV. Indications for revision included aseptic loosening (76.3%) and prosthetic joint infection (23.7%). Six cementless stems with a tapered rectangular shape from three companies were used in all patients. Among them, SLR-Plus, SL-Plus MIA, and Corail stems were employed in most patients (40.8%, 23.7%, and 17.1%, respectively). The average length of these stems measured 171.7 mm (SD 27 mm; 122–215 mm). Radiographic results, Harris hip scores (HHS), complications, and survivorship were analyzed. The follow-up lasted for 7 years on average (range 3–11 years).

Results

The subsidence was observed in three hips (3.9%), and all stems achieved stable bone ingrowth. Proximal femoral bone restoration in the residual osteolytic area was found in 67 hips (88.2%), constant defects in nine hips (11.8%), and increasing defects in 0 cases. There was no evidence of stem fractures and stem loosening in this series. The mean HHS significantly improved from 32 (range 15–50) preoperatively to 82 (range 68–94) at the last follow-up (t = − 36.297, P < 0.001). Five hips developed prosthesis-related complications, including three infection and two dislocation cases. The mean 5- and 10-year revision-free survivorships for any revision or removal of an implant and reoperation for any reason were 94.6% and 93.3%, respectively. Both mean 5- and 10-year revision-free survivorships for aseptic femoral loosening were 100%.

Conclusion

Conservative femoral revision using short cementless stems with a tapered rectangular shape can provide favorable radiographic outcomes, joint function, and mid-term survivorship with minimal complications. Of note, a sclerotic proximal femoral bone shell with continued and intact structure and enough support strength is the indication for using these stems.

Graphical Abstract

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

With the rate of total hip arthroplasty (THA) mounting rapidly, the rate of revision THA also has been on the rise annually, the number of procedures being projected to increase from 40,800 in 2005 to 96,700 in 2030 [1]. A challenge posed by the femoral revision is various degrees of bone defects, particularly Paprosky II–IV [2], which result in insufficient support for the prosthesis, thus, leading to subsidence, loosening, and other serious complications [3,4,5,6].

A variety of components have been developed to manage severe femoral bone loss, mainly including extensively coated stems [7] and modular fluted tapered stems [8, 9]. However, several complications, including substantial stress shielding, fatigue fractures, and corrosion at several junctions, have also been reported to be associated with these stems [7,8,9]. Moreover, compared with Europeans and Americans, Asians have relatively shorter length and larger anterior bowing of the femur [10]; hence, long stems for revision are more likely to cause periprosthetic fractures and thigh pain. Considering the younger age of revision patients, fracture and infection can be catastrophic for them due to the residual bone mass failing to withstand future revisions.

The use of cementless stems with a tapered rectangular cross-sectional shape not only achieved excellent long-term results in the primary replacement [11] but also attained acceptable outcomes in the hip revision with limited bone defects [12,13,14]. This type of component is designed to accommodate proximally located bony defects and provide enhanced load transfer from the proximal to the distal femur [12], particularly providing initial secure axial positioning and excellent anti-rotation stability [13]. Furthermore, the operative technique involving these stems is simple, which shortens the operation time, reduces intraoperative bleeding, and, more importantly, preserves more host bone mass, leaving the opportunity for possible re-revision [14]. However, to our knowledge, reports are still scanty on the application of these stems to address severe femoral defects.

This retrospective study reviewed a cohort of consecutive patients with Paprosky II-IV femoral bone loss who had been treated with short cementless stems with a tapered rectangular shape, and the purpose was to use a conservative femoral revision strategy to resolve complex femoral bone defects and reduce the risk of intraoperative fractures and postoperative complications. This study aimed to answer 4 questions: (1) What are the surgical indications for using this type of stems? (2) Will joint function improve in terms of the Harris Hip Score (HSS) after conservative femoral revision? (3) What are the postoperative complications? and (4) What is the medium- and long-term survival rate of these stems?

Patients and methods

Demographics of patients

The medical records of patients who had undergone revision hip arthroplasty by an experienced orthopedic surgeon (LC) were reviewed between January 2012 and December 2020. Patients were included if they underwent revision THA using the short cementless stems with a tapered rectangular shape for selected Paprosky II–IV bone defects. Patients receiving follow-up < 2 years and having incomplete data were excluded. Finally, 73 patients (76 hips) were included. The preoperative femoral bone defects were identified according to Paprosky classification [2] as follows: 54 cases of type II, 11 cases of type IIIA, 7 cases of type IIIB, and 4 cases of type IV. The reasons for femoral stem revision included aseptic loosening (n = 58; 74.2%) and prosthetic joint infection (PJI) (n = 18; 23.7%). Replacement of a cemented stem was performed in 8 revised hips, and combined acetabular revision was performed in 66 hips. Demographic data of all cases were strictly recorded (Tables 1 and 2).

Detailed information of stems

Six cementless stems with a tapered rectangular shape from three companies were used in all patients (Fig. 1). Among them, SLR-Plus, SL-Plus MIA, and Corail stems were used in most patients (40.8%, 23.7%, and 17.1%, respectively). SLR-Plus, SL-Plus, and SL-Plus MIA stems are made of a titanium-6 aluminum-7 niobium (Ti-6Al-7Nb) alloy, and the first two stems have a grit-blasted surface, while the last stem has a hydroxyapatite-coating. Corail, Polar, and Alpha-conserve type I stems are made of titanium alloy and have hydroxyapatite coating (Table 3). The data of different stems are detailed in Fig. 2, and the average length of the stems was 171.7 mm (SD 27 mm; 122–215 mm). The heads of the following diameters were used: 22 mm in 1 procedure (1.3%), 28 mm in 17 procedures (22.4%), 32 mm in 36 procedures (47.4%), 36 mm in 21 procedures (27.6%), and 40 mm in 1 procedure (1.3%). A metal head and high crosslinked polyethylene liner were used in most patients (53.9% and 89.5%, respectively). The top three diameters of the cups used were as follows: 58 mm in 15 cases (22.7%), 56 mm in 8 cases (12.1%), and 60 mm in 7 cases (10.6%) (Fig. 3).

Surgical technique

A posterior approach was used in all cases. Tissue and fluid specimens for histological analysis and microbial culture were routinely harvested. After joint dislocation, an extractor was employed to try to pull out the stem. If this procedure was difficult, the ETO was performed. According to the preoperative radiographs and intraoperative findings, the femoral bone defect was checked again. Then, the stability of the acetabular cup was also evaluated by using a scalpel to pass through the interface between the implant and the bone or Allis forceps to tug the implant. If this procedure was uneventful, the component was considered reliably fixed. If the acetabular cup loosened, the bone defect was also assessed after prosthesis removal. According to the degree of acetabular bone defect, a new prosthesis was implanted. Then, the remaining femoral canal was prepared with reamers under direct vision. If the intraoperatively determined bone conditions indicated that the shaft had the risk of fracture, the use of a titanium band cerclage was recommended to protect the integrity of the bone shell before starting the preoperative process with the rasp. Decisions about the length and size of the components and limb length were made with the assistance of fluoroscopy. After repeated confirmation of joint stability, non-absorbable sutures were used to attach the remaining abductors to the lateral part of the greater tuberosity, and then, the surgical incision was sutured layer by layer.

Medication regimen

All patients were intravenously given 1.5 g tranexamic acid within 1 h before surgery and 0.5 g tranexamic acid (q12h) after operation for 3 days. After surgery, peroxib sodium (40 mg, q12h) was administered intravenously for 7 days, followed by oral celecoxib (120 mg, qd) for 1 month. For aseptic loosening, patients received intravenous 1.5 g cefuroxime sodium within 1 h before surgery and every 12 h for 24 h after surgery. For PJI, patients received intravenous sensitive antibiotics within 1 h before surgery and intravenous and intra-articular injection of sensitive antibiotics after surgery, which was consistent with our previous study [15].

Postoperative rehabilitation

In the cases of aseptic loosening, patients who had Paprosky II femoral bone defect and did not use the tantalum block, cup, or cage for acetabular bone defect, were allowed to gradually engage in weight-bearing after surgery, but with a walker or crutches, for 6–8 weeks. If patients had Paprosky III–IV femoral bone defects or received tantalum cup or cage for acetabular bone defect, they had to be bedridden for 4–6 weeks following the operation, and then, a walker or crutches were used to assist gradual weight-bearing for 4–6 weeks. Quadriceps isometric contraction and ankle pump training were required for every patient after the operation, and the intensity of training depended on each patient’s conditions. In the cases of PJI, the patient was strictly confined to bed for 2 weeks, during which antibiotics were administered by intravenous and intra-articular injection for anti-infective treatment.

Follow-up and assessments

Two orthopedic surgeons who did not participate in surgery reviewed patients at 1, 3, 6, and 12 months postoperatively and then at yearly intervals. The evaluation included radiological measurements, functional scores, complications, and survival. When patients could not return for follow-up, telephone and mail surveys were used to obtain information.

The axial stem subsidence, defined as the distance between the lesser trochanter and the tip of the prosthesis, was measured using bone-prosthetic landmarks [16]. The measured subsidence was defined as the difference between immediate postoperative radiographs and radiographs at a final follow-up. The femoral implant stability was radiographically classified, according to the criteria of Engh et al., as stable through osseointegration, fibrous stable, and unstable [17]. Proximal bone restoration in residual osteolytic areas was subjectively classified as osseous restoration, constant defects, or increasing defects, according to the criteria of Böhm et al. [18]. The Harris Hip Score (HHS) was used for the comparison of joint function before and after surgery. Prosthesis-related complications were assessed, including infection, dislocation, loosening, fracture, and thigh pain. The Kaplan-Meier method was used to analyze the survival of all patients.

Statistical analysis

The Mann–Whitney U test was performed to examine any differences between pre- and postoperative HHS. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS v. 18.0 software (SPSS, USA) with statistical significance set at a P-value < 0.05.

Results

All cases were followed for an average of 7 years (range 3–11 years). The subsidence was observed in three hips (3.9%), in which one hip subsided for 3 mm (type IIIA), one hip subsided for 5 mm (type IIIB), and the other hip subsided for 9 mm (type IV). All stems achieved stable bone ingrowth. Proximal femoral bone restoration in the residual osteolytic area was observed in 67 hips (88.2%), constant defects were found in nine hips (11.8%), and no increasing defects appeared. Union was seen radiographically in all cases of ETO. There was no evidence of stem fractures and stem loosening, including radiolucent lines, osteolysis, migration, and distal pedestal formation, in this series. Typical cases are shown in Figs. 4 and 5.

The mean HHS improved significantly from 32 (15–50) preoperatively to 82 (68–94) at the last follow-up (t = − 36.297, P < 0.001) for all patients.

A total of five patients had prosthesis-related complications. The most common complication was infection, which occurred in three patients. After one-stage revision, one case underwent debridement and exclusion because of poor infection control. A new prosthesis was re-implanted 3 months after surgery, and open reduction for dislocation was performed 6 months later. The other two cases developed PJI 2 and 3 years after surgery, respectively. Of them, one underwent debridement, and the other received one-stage revision. Dislocation occurred in two patients 1 month after surgery. One case was treated with open reduction, and another case was again dislocated 1 year after open reduction and had to undergo revision THA.

Both mean 5- and 10-year revision-free survivorships for any revision or removal of an implant and reoperation for any reason were 94.6% and 93.3%, respectively (Fig. 6). Both mean 5- and 10-year revision-free survivorships for aseptic femoral loosening were 100%.

Discussion

Many scholars prefer to use long, large-diameter, versatile stems to obtain favorable outcomes in the short- and mid-term periods, but related severe complications also emerge [19,20,21]. In these situations, relatively shorter cementless stems with specific morphological features may be an alternative for femoral revision. Although stem designs have evolved over the past 30 years for a variety of reasons, this type of stem still has its value in revision or complex primary settings [11].

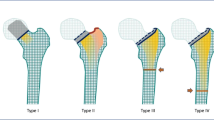

Chang et al. [22] reported that the rectangular tapered cementless stem could achieve excellent initial stability in any morphologic shape of the femur due to its two main features. On the one hand, the rectangular cross-sectional shape provides four-point fixation along the four corners within the femoral canal, contributing to rotational stability. On the other hand, the dual-tapered shape allows for further endosteal engagement, greater stem-diaphyseal diametric mismatch, and a resultant increase in circumferential compression of the implant, ensuring axial stability (Fig. 7). Although our study included stems from different companies, their design concepts were consistent with the above characteristics. Compared with long cylindrical stems and tapered fluted stems [2, 23, 24], the stems used in this study were shorter in length but greater in medial and lateral transverse diameters, which allows the stem to be engaged at the canal of proximal femur with intact cortex without estimating the extent of femoral bone defect. Moreover, the tapered stems only needed a minimum intact segment of 1.5–2.5 cm to obtain adequate initial fixation stability [25], which was shorter than 5–7 cm required by cylindrical stems [26]. Russell et al. [27] revealed that average loads to produce 150-μm displacement or failure were higher for tapered stems than for cylindrical stems.

The fixation of two types of stems. Compared with the cylindrical stem fixed at the distal femur through surface contact (B, D), the taper stem obtains further endosteal engagement and a resultant increase in circumferential compression of the implant (A) as well as greater resistance to rotation by the way of point fixation (C)

The indication for a long cylindrical stem fixed distally in patients with severe bone defects [28, 29] does not apply to the short tapered rectangular stem, we believe that the selection principles of the latter should conform to the following: a continued and intact proximal femoral bone shell and sclerotic proximal femoral bone strong enough to support the stems. Moreover, three points should also be emphasized: (1) the rasping of the femur medullar cavity should be gentle, not like during the initial THA, and a cable should be used if necessary; (2) residual bone cement in the distal medullar cavity of the femur does not need to be forcibly removed, to avoid extra bone loss and fracture; (3) early postoperative loading of patients should be avoided. If the aforementioned conditions are satisfied, the complicated surgical procedure will become easier and faster, consequently resulting in less bleeding and minimal complications.

A study reported a high rate of subsidence (16.1%–23.6%) in Paprosky I–IV femoral bone loss treated by modular and monoblock-tapered fluted titanium tapered stems [30], the rate being considerably higher than our results (3.9%). In our opinion, the disparity could be ascribed to (1) although both were tapered stems, the stem with wedge-shaped geometry used in this study was “point-fixed”, while the others used in previous studies were “face-fixed”, which impairs the endoosseous blood supply and affects bone remodeling; (2) sufficient press-fit is beneficial for the dual-tapered cementless stem to accomplish excellent initial stability; (3) our patients with severe bone defects were instructed to stay long in bed, which is critical since it allowed enough time for osseointegration. The latter two points were also supported by Zhang et al. [25], who revealed that insufficient press-fit and premature weight bearing were the main factors responsible for subsidence. Although radiographic subsidence was observed in three hips, none of them had clinical failure requiring reoperation, due to “secondary stability”, meaning the tapered stem with a larger diameter of the proximal portion can achieve incremental fixation with stem subsidence [27].

The osseointegration rate in our series was up to 100% in contrast to 83.5% reported with the Wagner SL revision component [31] and 56% with the modular ExtrêmeTM (Mark I) stem [32]. This finding is supported by a previous report [22], revealing that the “fit without fill” technique of tapered rectangular stems is conducive to preserving the blood supply of the endosteum, which can, in turn, promote bone regeneration, thus, finally restoring femoral bone stock and achieving the two-stage biological fixation. Both excellent bone ingrowth and long-term stability are important factors in reducing the incidence of thigh pain, which explains our results of no cases having thigh pain. Additionally, the stiffness mismatch between bone and prosthesis is also responsible for thigh pain [33]. Compared to the cobalt-chromium alloy, the elastic modulus of titanium alloy is closer to the femur shaft [34, 35], which is another advantage of this type of stem in easing thigh pain.

Regarding the studies on short tapered cementless stems for femoral revision (Table 4), the HHS in the current study was similar to those reported by Uriarte et al. [14] and Chang et al. [22], showing that final results were ≥ 80 points. However, Korovessis et al. [12] and Wang et al. [36] achieved 65.5 and 68.1 points at the last follow-up, respectively. The main reasons were different degrees of femoral defects and lower preoperative HHS in the latter. Furthermore, as PJI was treated by a one-stage revision in this cohort, the soft tissue around the hip could instantly obtain enough tension after surgery, and the combined systematic rehabilitation training compensated the disadvantages of long-term bed rest, consequently improving joint function and accelerating the rehabilitation process [37,38,39,40].

Our study was subject to several limitations. First, this was a retrospective study with a small sample size, which potentially introduced bias. Second, the advanced age and poor health of patients who presented with significant bone loss limited complete follow-up. Third, this study lacked a control group. Therefore, subsequent studies should focus on the comparison of efficacy between the stems used in this study and other tapered stems in the long-term follow-up.

Conclusions

Using the short cementless stems with a tapered rectangular shape, conservative femoral revision could obtain promising radiographic results, such as low subsidence rate and excellent osseointegration, rapid functional recovery, and few complications, as well as favorable survivorship in the setting of selected Paprosky II–IV bone defects at a mean seven-year follow-up. Notably, the indication for selecting these stems should be strictly followed to ensure an excellent outcome.

Availability of data and materials

This study was carried out in the First Affiliated Hospital of Xinjiang Medical University (137 South LiYuShan Road, Urumqi, Xinjiang, China). The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- THA:

-

Total hip arthroplasty

- HSS:

-

Harris hip score

References

Kurtz S, Ong K, Lau E, Mowat F, Halpern M. Projections of primary and revision hip and knee arthroplasty in the United States from 2005 to 2030. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89:780–5. https://doi.org/10.2106/JBJS.F.00222.

Paprosky WG, Greidanus NV, Antoniou J. Minimum 10-year-results of extensively porous-coated stems in revision hip arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1999;369:230–42. https://doi.org/10.1097/00003086-199912000-00024.

Khan Y, Arora S, Kashyap A, Patralekh MK, Maini L. Bone defect classifications in revision total knee arthroplasty, their reliability and utility: a systematic review. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2023;143:453–68. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00402-022-04517-y.

Soleilhavoup M, Villatte G, Cambier S, Descamps S, Boisgard S, Erivan R. Does metaphyseal modularity in femoral revision stems have a role in treating bone defects less severe than IIIB? Clinical and radiological results of a series of 163 modular femoral stems. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2022;108:103353. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.otsr.2022.103353.

Scuderi GR, Weinberg M. Classification of bone loss with failed stemmed components in revision total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2022;37:S258–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arth.2021.12.015.

Logoluso N, Pedrini FA, Morelli I, De Vecchi E, Romanò CL, Pellegrini AV. Megaprostheses for the revision of infected hip arthroplasties with severe bone loss. BMC Surg. 2022;22:68. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12893-022-01517-y.

Roberson JR. Proximal femoral bone loss after total hip arthroplasty. Orthop Clin North Am. 1992;23:291–302.

Otero JE, Martin JR, Rowe TM, Odum SM, Mason JB. Radiographic and clinical outcomes of modular tapered fluted stems for femoral revision for Paprosky III and IV femoral defects or Vancouver B2 and B3 femoral fractures. J Arthroplasty. 2020;35:1069–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arth.2019.11.039.

Richards CJ, Duncan CP, Masri BA, Garbuz DS. Femoral revision hip arthroplasty: a comparison of two stem designs. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2010;468:491–6. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11999-009-1145-7.

Lee KJ, Kim BS, Kim KT, Jung GH. Three-dimensional morphologic features of Asian atypical femur and clinical implications of cephalomedullary nail fixation: computational measurement at actual size. Injury. 2022;53:4090–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.injury.2022.09.044.

Staats K, Vertesich K, Sigmund IK, Böhler C, Windhager R, Kolb A. Thirty-year minimum follow-up outcome of a straight cementless rectangular stem. J Arthroplasty. 2023;19:S0883-5403(23)00664-2. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arth.2023.06.028.

Korovessis P, Repantis T. High medium-term survival of Zweymüler SLR-plus stem used in femoral revision. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2009;467:2032–40. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11999-009-0760-7.

Affatato S, Comitini S, Fosco M, Toni A, Tigani D. Radiological identification of Zweymüller-type femoral stem prosthesis in revision cases. Int Orthop. 2016;40:2261–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00264-016-3141-3.

Uriarte I, Moreta J, Cortés L, Bernuy L, Aguirre U, Martínez de Los Mozos JL. Revision hip arthroplasty with a rectangular tapered cementless stem: a retrospective study of the SLR-Plus stem at a mean follow-up of 4.1 years. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol. 2020;30:281–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00590-019-02578-1.

Ji B, Wahafu T, Li G, Zhang X, Wang Y, Momin M, Cao L. Single-stage treatment of chronically infected total hip arthroplasty with cementless reconstruction: results in 126 patients with broad inclusion criteria. Bone Joint J. 2019;101-B:396–402. https://doi.org/10.1302/0301-620X.101B.

Restrepo C, Mashadi M, Parvizi J, Austin MS, Hozack WJ. Modular femoral stems for revision total hip arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2011;469:476–82. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11999-010-1561-8.

Engh CA Jr, Hopper RH Jr, Engh CA Sr. Distal ingrowth components. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2004;420:135–41. https://doi.org/10.1097/00003086-200403000-00019.

Böhm P, Bischel O. Femoral revision with the Wagner SL revision stem: evaluation of one hundred and twenty-nine revisions followed for a mean of 4.8 years. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2001;83:1023–31.

Weeden SH, Paprosky WG. Minimal 11-year follow-up of extensively porous coated stems in femoral revision total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2002;17:134–7. https://doi.org/10.1054/arth.2002.32461.

Inoue D, Restrepo C, Nourie B, Hozack WJ. Clinical results of revision hip arthroplasty for neck-taper corrosion and adverse local tissue reactions around a modular neck stem. J Arthroplasty. 2020;35:S289–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arth.2020.02.057.

Herry Y, Viste A, Bothorel H, Desmarchelier R, Fessy MH. Long-term survivorship of a monoblock long cementless stem in revision total hip arthroplasty. Int Orthop. 2019;43:2279–84. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00264-018-4186-2.

Chang JD, Kim TY, Rao MB, Lee SS, Kim IS. Revision total hip arthroplasty using a tapered, press-fit cementless revision stem in elderly patients. J Arthroplasty. 2011;26:1045–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arth.2011.03.020.

Palumbo BT, Morrison KL, Baumgarten AS, Stein MI, Haidukewych GJ, Bernasek TL. Results of revision total hip arthroplasty with modular, titanium-tapered femoral stems in severe proximal metaphyseal and diaphyseal bone loss. J Arthroplasty. 2013;28:690–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arth.2012.08.019.

Huang Y, Shao H, Zhou Y, Gu J, Tang H, Yang D. Femoral bone remodeling in revision total hip arthroplasty with use of modular compared with monoblock tapered fluted titanium stems: the role of stem length and stiffness. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2019;101:531–8. https://doi.org/10.2106/JBJS.18.00442.

Zhang Y, Zhang Y, Sun JN, Hua ZJ, Chen XY, Feng S. Comparison of cylindrical and tapered stem designs for femoral revision hip arthroplasty. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2020;21:411. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12891-020-03461-5.

McAuley JP, Engh CA Jr. Femoral fixation in the face of considerable bone loss:cylindrical and extensively coated femoral components. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2004;429:215–21. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.blo.0000150274.21573.f4.

Russell RD, Pierce W, Huo MH. Tapered vs cylindrical stem fixation in a model of femoral bone deficiency in revision total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2016;31:1352–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arth.2015.12.008.

Amanatullah DF, Howard JL, Siman H, Trousdale RT, Mabry TM, Berry DJ. Revision total hip arthroplasty in patients with extensive proximal femoral bone loss using a fluted tapered modular femoral component. Bone Joint J. 2015;97-B:312–7. https://doi.org/10.1302/0301-620X.97B3.34684.

Viste A, Perry KI, Taunton MJ, Hanssen AD, Abdel MP. Proximal femoral replacement in contemporary revision total hip arthroplasty for severe femoral bone loss: a review of outcomes. Bone Joint J. 2017;99-B:325–9. https://doi.org/10.1302/0301-620X.99B3.BJJ-2016-0822.R1.

Yacovelli S, Ottaway J, Banerjee S, Courtney PM. Modern revision femoral stem designs have no difference in rates of subsidence. J Arthroplasty. 2021;36:268–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arth.2020.07.078.

Gutiérrez Del Alamo J, Garcia-Cimbrelo E, Castellanos V, Gil-Garay E. Radiographic bone regeneration and clinical outcome with the Wagner SL revision stem: a 5-year to 12-year follow-up study. J Arthroplasty. 2007;22:515–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arth.2006.04.029.

Benoist J, Lambotte JC, Polard JL, Huten D. High rate of fracture in the cementless modular Extrême™ (Mark I) femoral prosthesis in revision total hip arthroplasty: 33 cases at more than 5 years’ follow-up. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2013;99:915–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.otsr.2013.08.007.

Kang JS, Moon KH, Park SR, Choi SW. Long-term results of total hip arthroplasty with an extensively porous coated stem in patients younger than 45 years old. Yonsei Med J. 2010;51:100–3. https://doi.org/10.3349/ymj.2010.51.1.100.

Hazlehurst KB, Chang JW, Stanford M. A numerical investigation into the influence of the properties of cobalt chrome cellular structures on the load transfer to the periprosthetic femur following total hip arthroplasty. Med Eng Phys. 2014;36:458–66. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.medengphy.2014.02.008.

Sumner DR. Long-term implant fixation and stress-shielding in total hip replacement. J Biomech. 2015;48:797–800. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbiomech.2014.12.021.

Wang J, Dai WL, Lin ZM, Shi ZJ. Revision total hip arthroplasty in patients with femoral bone loss using tapered rectangular femoral stem: a minimum 10 years’ follow-up. Hip Int. 2020;30:622–8. https://doi.org/10.1177/1120700019859809.

Ji B, Li G, Zhang X, Wang Y, Mu W, Cao L. Effective treatment of single-stage revision using intra-articular antibiotic infusion for culture-negative prosthetic joint infection. Bone Joint J. 2020;102-B:336–44. https://doi.org/10.1302/0301-620X.102B3.BJJ-2019-0820.R1.

Li Y, Zhang X, Ji B, Wulamu W, Yushan N, Guo X, Cao L. One-stage revision using intra-articular carbapenem infusion effectively treats chronic periprosthetic joint infection caused by Gram-negative organisms. Bone Joint J. 2023;105-B:284–93. https://doi.org/10.1302/0301-620X.105B3.

Ji B, Li G, Zhang X, Wang Y, Mu W, Cao L. Multicup reconstruction technique for the management of severe protrusio acetabular defects. Arthroplasty. 2021;3:26. https://doi.org/10.1186/s42836-021-00081-9.

Ji B, Xu B, Guo W, Rehei A, Mu W, Yang D, Cao L. Retention of the well-fixed implant in the single-stage exchange for chronic infected total hip arthroplasty: an average of five years of follow-up. Int Orthop. 2017;41(5):901–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00264-016-3291-3.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the Department of Microbiology and the Department of Pharmacy of our hospital for the assistance during the treatment.

Funding

This study was supported by grants from Research and Development of Key Intelligent Diagnosis and Treatment Technology and Equipment for Bone and Joint Diseases in Xinjiang (No.2022A03011), the Natural Science Foundation of the Xinjiang Autonomous Region (No.2023D01E11 and No. 2021D01C331), and the Special Fund for Youth Scientific Research of the First Affiliated Hospital of Xinjiang Medical University in 2022 (No. 2022YFY-QKMS-03).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.C.: design of the work, surgeries, manuscript revision; Y.L.: manuscript writing, design of the work, surgeries;. X.Z.: manuscript writing, design of the work, surgeries; B.J.: surgeries; W.W.: surgeries; N.Y.: data analysis, data acquisition; X.G.: data acquisition. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was conducted in accordance with the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the institutional review board of the First Affiliated Hospital of Xinjiang Medical University (Approval number: k202305-08). Informed consent was obtained from each patient.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

Li Cao and Xiaogang Zhang are the member of the Editorial Board of Arthroplasty and other authors declare that they have no competing interests. All authors were not involved in the journal’s review of or decisions related to this manuscript.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, Y., Zhang, X., Ji, B. et al. Conservative femoral revision using short cementless stems with a tapered rectangular shape for selected Paprosky II–IV bone defects: an average seven-year follow-up. Arthroplasty 6, 38 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s42836-024-00251-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s42836-024-00251-5